KLAATU YOU (INTRO)

By:

January 1, 2020

This year’s weekly “enthusiasm” series, here at HILOBROW, will be dedicated to pre-Star Wars science fiction movies.

The unprecedented success of George Lucas’s 1977 space opera transformed the science fiction movie genre, for better and worse. On the plus side, science fiction films became an ever more popular genre, and many of my favorite examples of the genre might never have been made had Star Wars not paved the way; also, if you like computer-generated special effects, thank George Lucas. However, sci-fi movies post-Star Wars would be increasingly required to be conceived of as sprawling blockbusters; merchandising considerations would drive production decisions; and the special effects are the only innovative or memorable thing about far too many sci-fi movies since Star Wars.

Once up on a time, sci-fi movies were lowbrow or highbrow, or in some extraordinary cases high-lowbrow; Star Wars demonstrated how very profitable a middlebrow sci-fi spectacle could be.

Acting on the assumption that we may have lost more than we’ve gained, since 1977, I’ve invited 52 HILOBROW contributors to revisit their favorite pre-Star Wars sci-fi movies. The weekly series KLAATU YOU kicks off tomorrow. Enjoy!

Below, I’ve made a few preliminary notes — based on the ~20 installments I’ve received, so far — about the series’ themes.

One immediately obvious point of difference between pre- and post-Star Wars sci-fi movies is: the special effects. Mechanical (or practical, physical) effects are clumsier, less convincing than the computer-generated effects that Star Wars would help pioneer and popularize. Today, however, many of us find the use of miniatures and matte paintings, puppetry and pyrotechnics — all of which George Lucas also uses — more and more engaging. From the Schüfftan process (a technique that angles partially reflective mirrors in front of the camera to combine life-size actors and miniature models into a single, to-scale frame) used in Lang’s Metropolis to the hidden wires, mirror shots, and large-scale rotating sets in Kubrick’s 2001, there’s something admirable and charismatic about mechanical effects.

Yes, Baudrillard’s theory of the uncanny simulacrum, yes, yes, no arguments from us. But what I’m talking about is the karaoke effect: that feeling one gets when watching someone struggle to do a proper job with faulty equipment. Almost despite oneself, one roots for them to succeed. We’re all in this together! The karaoke effect is, I’d just add, the exact opposite of the MST3K effect. In fact, one of the movies we’ll enthuse about — Joseph M. Newman and Jack Arnold’s This Island Earth (1955) — was the subject of ridicule in Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie. Hate-watching is anathema, here at HILOBROW.

Michael Lewy, writing about This Island Earth, enjoys how matte paintings are integrated with the movie’s live-action footage: “Although obviously fake, these matte paintings are for me much more powerful than today’s CGI… The simplicity of this 1950s effect is very charming.” [Check out Michael’s own gorgeous experiments with practical effects here.] “Whale’s technique to make Griffin invisible delights me,” Rob Wringham writes about The Invisible Man (1933). “Black velvet shot against an identical backdrop before placing him into the action using double exposure, his clothes plausibly filled but head and hands vanished. It’s inspiring in its clever, potting shed-like resourcefulness.”

Even when the effects, set design, costumes, etc., in pre-Star Wars sci-fi movies truly are cheesy, they can elicit from us tender, protective feelings that CGI never will. The greatest thing about David Lane’s mid-1960s Thunderbirds franchise, Mark Kingwell claims, is “the absurd complexity of the staging sequences…. Getting the smart-casual boys, in Sixties desert boots, polo necks, and suede vests, into their ships and sashed blue uniforms, with matching wedge hats, took forever. Is it an emergency or not?” Erik Davis, meanwhile, is quick to note that beneath the “absurd lineaments” of the “inflatable pumpkin-hued beach ball with claws,” in John Carpenter’s and Dan O’Bannon’s Dark Star (1974), can be perceived “the Giger horror” that O”Bannon and Ridley Scott would unleash on us — with Alien — just a few years later. The first time as comedy, the second time as tragedy: One of HILOBROW’s favorite tropes.

Sure, Barbarella may have “sexy spacesuits designed by Paco Raban,” sniffs Mimi Lipson, writing about Mike Kuchar’s Sins of the Fleshapoids (1965), but Fleshapoids has “togas and flapper dresses and football helmets. The sets are a maze of bed sheets and plastic fruit. One million years in the future, shirtless lotharios lounge about on leopard-skin throws eating Clark bars and bags of Wise potato chips.” Note the appreciative, counter-MST3K tonality, here. HILOBROW’s contributors recognize “bad” special effects, set design, costumes, and so forth; but our instinctive response to these phenomena is affection, not scorn. This is engaged irony, not snark.

At the level of form, at least a couple of the movies under consideration in this series aren’t cheesy at all — but instead glorious, and/or productively estranging. “It’s as sleek and streamlined as an arrow, using cinema to tell a story not with words, but with spectacle and montage,” enthuses Gordon Dahlquist about Kubrick’s 2001 (1968). “At nearly 3 hours it could be on a plinth next to Brancusi’s Bird in Space.” Karinne Keithley Syers, writing about Godard’s Alphaville (1965), helps viewers perceive in it “choreographic thinking as a kind of acceleration into weirdness; a world-building communicated instantaneously in the evidence of altered embodiment; an off-kilter sequential possibility in narrative that lets us leap right into strange human experience in an imagined other world.”

Science fiction movies — like science fiction stories and novels — may extrapolate into the future worrisome contemporary trends in society, culture, the economy… but always, without fail, they predict that scientific and technological breakthroughs will have unintended consequences. It’s the Prometheus consideration: Humankind isn’t prepared to deal with the godlike powers we’re unleashing.

Star Wars, like the Flash Gordon serials to which Lucas pays semi-ironic homage, is gee-whiz optimistic about science and technology… with the sole exception of the Ming the Merciless-esque planet-destroying weapon. Contributors to HILOBROW’s series, however, tend to gravitate instead towards movies like Metropolis (1927), whose “rendering of technology as monstrous and devouring” Miranda Mellis finds mesmerizing. Writing about The Fly (1958), Vanessa Berry sees in the titular insect a synechdoche for the era: “In the Atomic Age tiny things held the potential for catastrophe, the ability to vaporize and mutate.”

HILOBROW’s contributors understand that science and technology aren’t the problem — instead, we are. Particularly when “we” are amoral government stooges: “Kiss Me Deadly,” writes Madeline Ashby about Robert Aldrich’s 1955 neo-noir sci-fi movie, “dares to join up the man hardened by the horrors of war and the people who create those horrors, the scientists and engineers of the war machine itself.” Michael Grasso, writing about The Andromeda Strain (1971), enjoys how the movie balances “the wonder of science and the fear of conspiracy…. Every discovery in the lab, every puzzle solved thanks to that gleaming cutting-edge equipment, seems to lead to more mystery, more secrets held by men and not nature.” Perhaps we’re neo-Luddites, skeptical of techno-boosterism and arrogant scientism; but this series’ contributors aren’t Luddites.

The man-vs.-machine dialectic is turned on its head, in Peter Fonda’s Idaho Transfer (1973). “In many science-fiction futures, the machine, programmed with our hubris, must be stopped,” writes Devin McKinney. “In Idaho Transfer, it isn’t machines that have betrayed us, but we who fail the machines.” [We’re very grateful to Devin for having introduced us to this truly obscure movie; it can be streamed, for free, here.] Carolyn Kellogg, meanwhile, notices something wonderful about the lack of advanced tech, in It Came from Outer Space (1953): “There’s a luxurious amount of screen-time when John and Ellen contemplate what he might have seen. They drive around the desert (and the Universal back lot) in a world entirely their own. … The way that they are present in that space and with each other is so impossibly different from our internet-connected moment that it seems like it was before electricity.”

“In my twenties,” reminisces Adrienne Crew about Michael Anderson’s Logan’s Run (1976), “I laughed at the film’s quickly dated 1970s aesthetics: the Dallas mall masquerading as a city of the future; Logan’s mirrored apartment; the rail system that looked like a Habitrail hamster tube-maze. Today, I seethe with anger over the domed city’s founders’ cruel decision to subject their children to a social order that offers false hope of ‘renewal.'” In this excerpt, we again discover how resistant HILOBROW contributors are to the allure of juvenile snarkiness. We also encounter one of this series’ key themes: a fierce resistance to the fatalistic assumption that utopia is but a pipe dream.

KLAATU YOU series contributors are fully aware that totalizing utopian social orders — which achieve harmony and eradicate dissensus through thought control, coercion, and forcing square pegs into round holes — are dystopian. In her installment on Metropolis, Miranda Mellis applauds the protagonist’s discovery of “the world of systematic oppression and suffering going on behind the scenes, as it were, of his pleasure garden of a life.” Matthew De Abaitua, writing about John Boorman’s Zardoz (1974), can muster sympathy for neither the movie’s utopians nor the barbarians at the gate: “Zed is a fascist. Eventually, his fellow savages — identically dressed — follow him into the commune. They set about relieving the immortals of the burden of eternal life. Many of the immortals welcome it: kill me, kill me, they plead.”

However, we’re anti-anti-utopians, not anti-utopians, here. Even within a depiction of a flawed, failed utopia — sometimes particularly so; I’m thinking of Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance, say, or Mary McCarthy’s The Oasis — we can glimpse the possibility of a non-coercive, non-totalizing utopia. “The movie is virtually toneless, unless that tone be the electrical hum of an abandoned, still functioning hospital,” notes Devin McKinney in his discussion of Idaho Transfer. “But it is warmed by the earnest, attractive faces of the young actors; by the prosaic vision of an egalitarian, non-sexist group structure, suggesting hope for the future.” The appeal of the Argonaut Folly was at an all-time high, in the latter half of the cultural era known as the Sixties (1964–1973). “The jokes, the wrestling, the horizontal postures: their tribal camaraderie is strong,” I write about Max Frost’s entourage, in my KLAATU installment on Barry Shear’s Wild in the Streets (1968). “They’re a living advertisement, for better and worse, for Max’s vision: an eroticized, non-repressive, egalitarian America. His means are iffy, but his ends? Sign me up.”

Star Wars expresses a certain amount of sympathy for aliens; there is some de-othering going on, in these movies. In fact, if the Star Wars semiotic square I cobbled together nearly a decade ago is as revelatory as I believed it to be then, “the most poignant aspect of Star Wars IV is not whether Luke will rescue Leia, but whether the Death Star will be completed — and then used to wipe out non-human species.” The ultimate stakes, in that movie, were genocide, politicide, ethnic cleansing, culturecide — though it’s unclear whether Lucas himself was aware of any of these themes. Alas, however, for every loveable Wookiee, there are anti-Semitic — both anti-Arab and anti-Jewish — stereotypes including the Bedouin-like Sand People, the scavenging Jawas, and the money-obsessed Watto. (Let’s not even begin to discuss Jar-Jar Binks.) Surely, however, pre-Star Wars movies weren’t one bit more enlightened?

They weren’t, for the most part! Still, KLAATU contributors point to several interesting counter-examples, where the monsters are revealed to be less than entirely monstrous, and the viewer may even find herself empathizing with alien invaders.

In one of Gordon Dahlquist’s notes on 2001, he asks us to consider “How HAL pleading for its life to the unspeaking, amplified-breathing, bug-helmeted astronaut flips the old sci-fi monster movie trope.” Peggy Nelson asks us to empathize with the mindfucking sentient planet in Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972): “It is revealed that the planet has been making golems out of itself for eons, yet only now, in encountering its “own” extraterrestrials, has it had anything outside itself to work with.” Speaking of empathy, “What I find most pleasurable about The Man Who Fell to Earth is that it’s more than just a science fiction film,” writes Ramona Lyons of Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 Bowie vehicle. “It’s an identity fantasy that draws you into David Bowie’s otherness, allowing you to put on his skin and experience it from all angles.”

Heartless, ruthless human beings, meanwhile, remain the true villains of many of our favorite pre-Star Wars sci-fi movies. “The antagonists, sinister billionaire Aristotle Bolt and his sidekick Mr. Deranian, want to use Tony and Tia as humint — to find oil, predict revolutions, and other wealth-building duties as assigned,” writes Sara Ryan about Escape to Witch Mountain (1975). “‘Wealth, gentlemen, is like flesh,’ Bolt explains. ‘It has to be nurtured and coddled.'” Brrr.

Fredric Jameson makes a good point when he privileges those science-fiction narratives that unveil a vision of a truly different world over those that merely offer a situation-specific response to a concrete historical dilemma. But it can be instructive and helpful to revisit the anxieties of past eras, particularly those that continue to survive and thrive today.

The divide, among Americans, between progressives and reactionaries, is no less volatile today than it was in 1971. Boris Sagal’s The Omega Man pits Charlton Heston against “analogues of the hippies, Black Panthers, and Weathermen who commanded cultural center stage at the time,” notes Carlo Rotella. “Heston, who caresses an automatic weapon while reciting dialogue along with the hippie musicians on the screen as he watches Woodstock over and over at a local movie theater, must figure out how to walk the line between coexistence with this new order and an all-out war of annihilation. Although the movie “aches to just let Neville mow down the freaks,” it doesn’t entirely give in to this urge. “Its restraint seems quaint now.”

Male fragility and rage, to name another concrete historical dilemma, is still very much with us. “Attack of the 50 Foot Woman was one of several late-1950s B-movies that featured men or humanoids who shrink or grow to outrageous proportions,” points out Lynn Peril in her essay on Nathan Hertz’s 1958 movie. “These size switcheroos were clearly meant to play on anxieties, be they atomic, maternal, or misogynistic.” Zardoz, claims Matthew De Abaitua, is “gloriously problematic.” Why? Because, “Like Taxi Driver and Joker, it rages against masculine impotency; unlike those movies, codified with American arthouse seriousness, its rage is served with such artistic hubris, that its reactionary potential is defused, rendered absurd.”

The blurring of the boundary between televised spectacle and real life, and the encroachment of commerce on every aspect of experience, isn’t a new concern. Elio Petri’s The Tenth Victim (1965) “regales the viewer with a wide selection of themes: weaponry, war between sexes, television culture, moral decay, and of course advertising,” writes Luc Sante. “[Ursula] Andress schemes to make her rubout of Mastroianni the centerpiece of a frantically choreographed commercial for Ming Tea.”

“The entire 1970s, economically austere, militarily precarious, environmentally collapsing, felt like one long funeral for the future,” writes Adam McGovern in his essay on Douglas Trumbull’s Silent Running (1972). “We know that the human race itself, and [eco-warrior Freeman Lowell’s] crusading type especially, is going extinct, and the film’s many lapses in logic … are swept away by the feeling of bad-dreamlike inexorability.”

Bad-dreamlike inexorability. As we enter 2020, who can’t relate?

I am very grateful to the KLAATU YOU series contributors — many of whom have donated their fees to the ACLU. Here’s the lineup:

Matthew De Abaitua on ZARDOZ | Miranda Mellis on METROPOLIS | Rob Wringham on THE INVISIBLE MAN | Michael Grasso on THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN | Gordon Dahlquist on 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY | Erik Davis on DARK STAR | Carlo Rotella on THE OMEGA MAN | Madeline Ashby on KISS ME DEADLY | Adam McGovern on SILENT RUNNING | Michael Lewy on THIS ISLAND EARTH | Josh Glenn on WILD IN THE STREETS | Mimi Lipson on BARBARELLA vs. SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS | Vanessa Berry on THE FLY | Lynn Peril on ATTACK OF THE 50 FOOT WOMAN | Peggy Nelson on SOLARIS | Adrienne Crew on LOGAN’S RUN | Ramona Lyons on THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH | Kio Stark on THE STEPFORD WIVES | Dan Fox on FANTASTIC PLANET | Chris Lanier on IKARIE XB-1 | Devin McKinney on IDAHO TRANSFER | Mark Kingwell on THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO | Luc Sante on THE TENTH VICTIM | William Nericcio on DEATH RACE 2000 | Rob Walker on CAPRICORN ONE | Gary Panter on ANGRY RED PLANET | David Levine on THE STEPFORD WIVES | Karinne Keithley Syers on ALPHAVILLE | Carolyn Kellogg on IT CAME FROM OUTER SPACE | Sara Ryan on ESCAPE TO WITCH MOUNTAIN | Lisa Jane Persky on PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE | Adam Harrison Levy on BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES | Gerald Peary on CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON | Susannah Breslin on A CLOCKWORK ORANGE | Seth on WAR OF THE WORLDS | James Hannaham on GOJIRA/GODZILLA | Lydia Millet on VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED | Matthew Daniel on FANTASTIC VOYAGE | Shawn Wolfe on ROLLERBALL | Erin M. Routson on WESTWORLD | Marc Weidenbaum on COLOSSUS: THE FORBIN PROJECT | Neil LaBute on 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA | Vicente Lozano on DAY OF THE DOLPHIN | Tom Roston on SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE | Katya Apekina on A BOY AND HIS DOG | Chelsey Johnson on THE BLOB | Heather Kapplow on SPACE IS THE PLACE | Brian Berger on THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS | Anthony Miller on THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL.

PS: Here a few other favorites that it would have been fun to include:

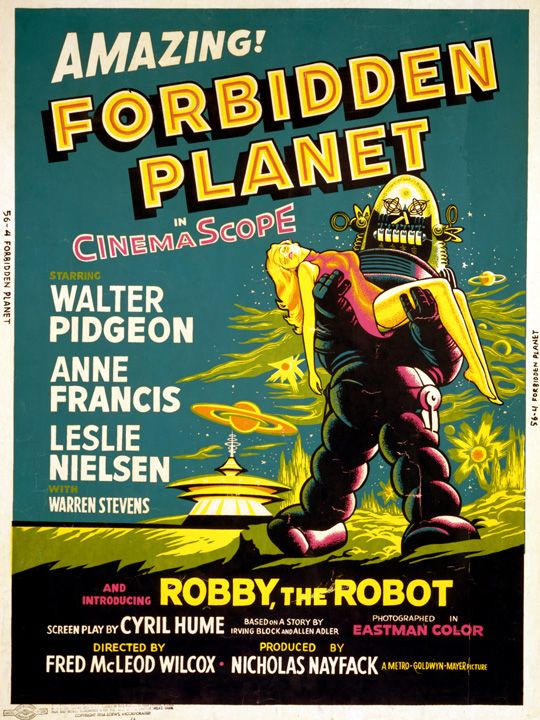

BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935) | CHARLY (1968) | DEMON SEED (1977) | DESTINATION MOON (1950) | DOCTOR X (1932) | DR JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1941) | EARTH VS THE FLYING SAUCERS (1956) | ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET OF THE APES (1971) | FIRST SPACESHIP ON VENUS (1962) | FLASH GORDON (1936-1940) | FORBIDDEN PLANET (1956) | FRANKENSTEIN (1931) | GAMERA, THE GIANT MONSTER (1965) | INVADERS FROM MARS (1953) | JE T’AIME, JE T’AIME (1968) | JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF THE EARTH (1959) | KRAKATIT (1948) | LA JETÉE (1962) | LES CRÉATURES (1966) | MARS NEEDS WOMEN (1967) | MONSTER A GO-GO! (1965) | MOTHRA (1961) | MYSTERIOUS ISLAND (1941) | NIGHT OF THE BIG HEAT (1959) | PANIC IN YEAR ZERO! (1962) | PLANET OF THE APES (1968) | PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES (1965) | ROBOT MONSTER (1953) | RODAN (1956) | SECONDS (1966) | SLEEPER (1973) | SON OF INGAGI (1940) | SOYLENT GREEN (1973) | TARANTULA (1955) | THE BEAST WITH A MILLION EYES (1955) | THE CREATION OF THE HUMANOIDS (1960) | THE CRAZIES (1973) | THE DAMNED (1963) | THE DAY OF THE TRIFFIDS (1962) | THE INCREDIBLE MELTING MAN (1977) | THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN (1957) | THE INVISIBLE MAN RETURNS (1940) | THE INVISIBLE WOMAN (1940) | THE ISLAND OF DR MOREAU (1933 OR 1977) | THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD (1951) | THE THING WITH TWO HEADS (1972) | THE TIME MACHINE (1960) | THX 1138 (1971) | VOYAGE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA (1961) | WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE (1951) | WIZARDS (1977) | WORLD ON A WIRE (1973) | X: THE MAN WITH X-RAY EYES (1963)

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: OWL | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM (INTRO) | VIRUS VIGILANTE | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM (INTRO) | TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM (4Q2021): NERDING | ARDUIN | KLINGON CONFIDENTIAL | MAP INSERTS | TIME | & 20 other nerdy passions. SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM (3Q2021): WARHOL’S WALT WHITMAN | 70, GIRLS, 70 | TYRAEL’S MIGHT | SHIRATO SANPEI | THE LEON SUITES | & 20 other never-realized cultural productions. FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2Q2021): DARK SHADOWS | MANNIX | GET SMART | THE ADDAMS FAMILY | I DREAM OF JEANNIE | & 20 other Sixties (1964–1973) TV shows. FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM (1Q2021): STEVEN UNIVERSE | TOP CAT | REN & STIMPY | SHE-RA AND THE PRINCESSES OF POWER | DRAGON BALL Z | & 20 other animated series. CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2020): “Sex Bomb” | “Going Underground” | “Soft South Africans” | “Typical Girls” | “Human Fly” | & 20 other Seventies (1974–1983) punk singles. KLAATU YOU (2020 weekly): ZARDOZ | METROPOLIS | DARK STAR | SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS | SOLARIS | & dozens of other pre-STAR WARS sci-fi movies. CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2019): THE TAKING OF PELHAM ONE TWO THREE | ROLLERBALL | BLACK SUNDAY | SORCERER | STRAIGHT TIME | & 20 other Seventies (1974–1983) action movies. SERIOCOMIC (2019 weekly): LITTLE LULU | VIZ | MARSUPILAMI | ERNIE POOK’S COMEEK | HELLBOY | & dozens of other comics. TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2018): LOONEY TUNES | THREE STOOGES | THE AVENGERS | ROCKY & BULLWINKLE | THE TWILIGHT ZONE | & 20 other Fifties (1954–1963) TV shows. WOWEE ZOWEE (2018 weekly): UNISEX | UNDER THE PINK | DUMMY | AMOR PROHIBIDO | HIPS AND MAKERS | & dozens of other Nineties (1994–2003) albums. KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2017): THE KILLERS | BANDE À PART (BAND OF OUTSIDERS) | ALPHAVILLE | HARPER | BLOW-UP | & 20 other Sixties (1964–1973) neo-noir movies. #SQUADGOALS (2017 weekly): THE WILD BUNCH | BOWIE’S BAND | THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP | THE HONG KONG CAVALIERS | VI ÄR BÄST! & dozens of other squads. GROK MY ENTHUSIASM (2016 weekly): THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF LUNCH | WEEKEND | MILLION YEAR PICNIC | LA BARONNE EMILE D’ERLANGER | THE SURVIVAL SAMPLER | & dozens more one-off enthusiasms. QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2016): “Tainted Love” | “Metal” | “Frankie Teardrop” | “Savoir Faire” | “Broken English” | & 20 other Seventies (1974–1983) new wave singles. CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2015): DARKER THAN YOU THINK | THE SWORD IN THE STONE | OUT OF THE SILENT PLANET | THIEVES’ HOUSE | QUEEN OF THE BLACK COAST | & 20 other Thirties (1934–1943) fantasy novels. KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2014): ALDINE ITALIC | DATA 70 | TORONTO SUBWAY | JOHNSTON’S “HAMLET” | TODD KLONE | & 20 other typefaces. HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2013): “Spoonin’ Rap” | “Rapper’s Delight” | “Rappin’ Blow” | “The Incredible Fulk” | “The Adventures of Super Rhyme” | & 20 other Seventies (1974–1983) hip-hop songs. KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2012): Justice or vengeance? | Kirk teaches his drill thrall to kiss | “KHAAAAAN!” | “No kill I” | Kirk browbeats NOMAD | & 20 other Captain Kirk scenes. KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM (2011): THE ETERNALS | BLACK MAGIC | DEMON | OMAC | CAPTAIN AMERICA | & 20 other Jack Kirby panels.