This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Fifties (1954–1963, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). Although it remains a work in progress, and is subject to change, this BEST ADVENTURES OF THE FIFTIES list complements and supersedes the preliminary “Best Fifties Adventure” list that I first published, here at HILOBROW, in 2013. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

The Fifties was the era of James Bond. Fleming’s first Bond book, Casino Royale, appeared in the cusp year of 1953; before 1964, he’d publish Live and Let Die, Moonraker, Diamonds Are Forever, From Russia, with Love, Dr. No, Goldfinger, For Your Eyes Only, Thunderball, The Spy Who Loved Me, and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. I enjoyed these books as an adolescent, but find them unreadable now. In contrast to Bond’s rococo thrills, Graham Greene, and John le Carré gave us morally ambiguous — yet suspenseful, exciting — espionage adventures. PS: Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, whose context is the complexity of guerrilla warfare and insurgency (vs. straightforward combat), is a favorite of General David Petraeus’s.

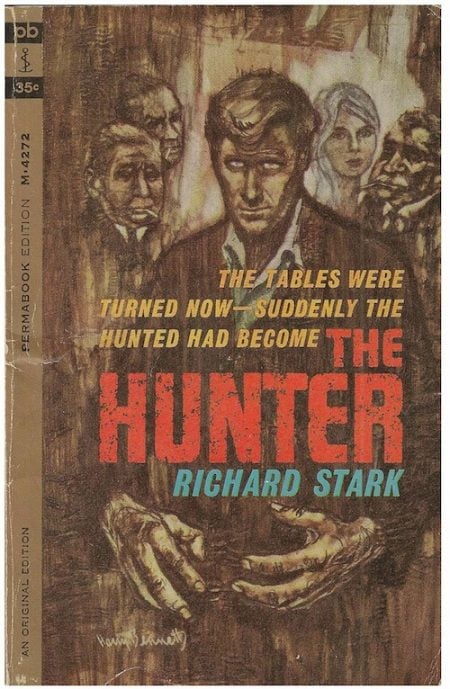

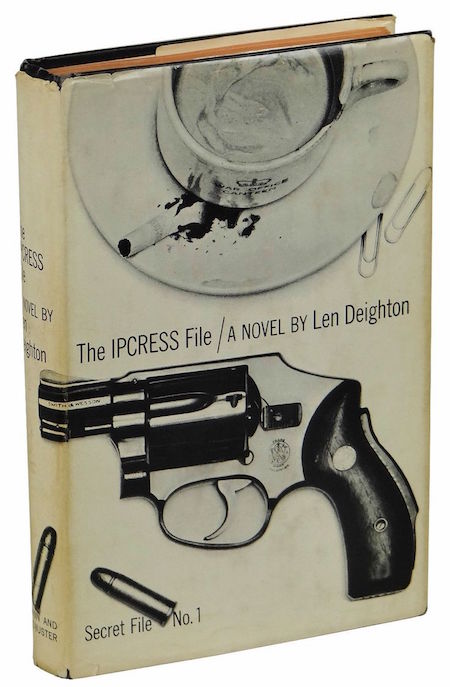

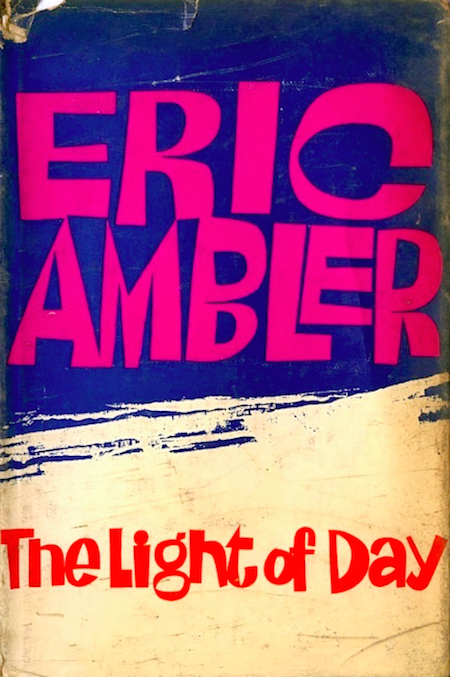

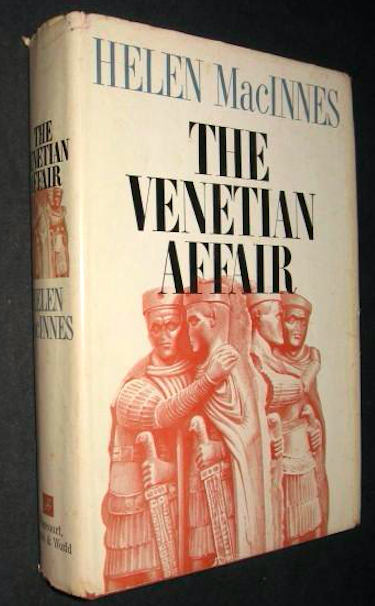

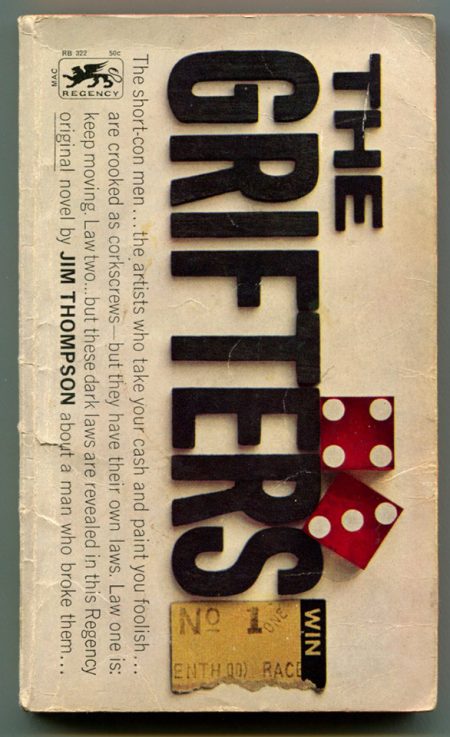

The Golden Age of adventure was in the rearview mirror, during the Fifties, but Alistair MacLean, Helen MacInnes, Geoffrey Household, and newcomers Lionel Davidson and Len Deighton, did some of their best work during these years. It was also a great era for caper adventures: Between 1954 and 1963, Richard Stark, Jim Thompson, Donald Hamilton, Lionel White, Ed McBain, Eric Ambler, Patricia Highsmith, Andrew Garve, and John D. MacDonald wrote some of the best crime novels of all time.

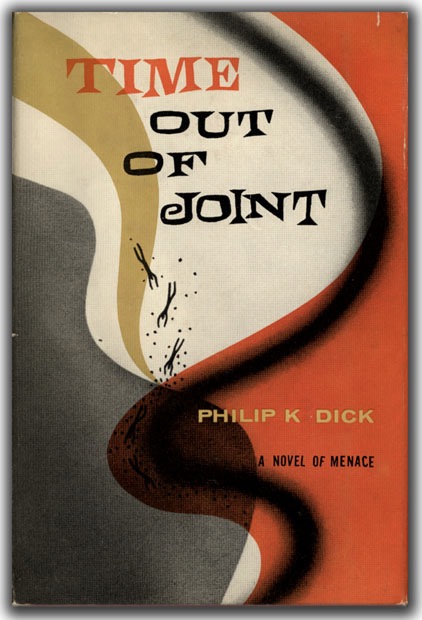

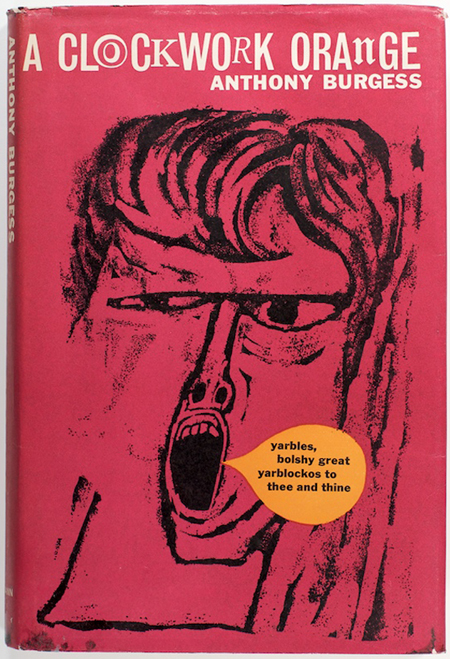

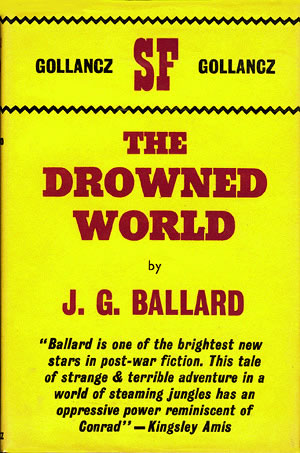

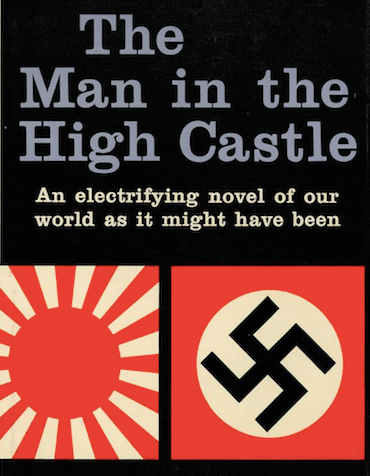

The apex of Cold War paranoia coincided with the apex of the so-called Golden Age of Science Fiction and Fantasy — by 1963, the New Wave era of these genres was visible on the horizon. Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword, Philip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint and The Man in the High Castle, Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination, Kurt Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan and Cat’s Cradle, Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World, and Michael Moorcock’s The Stealer of Souls already contain New Wave elements. Yet they’re not so self-conscious as New Wave science fiction and fantasy; the pleasure they offer to the reader is less rarified and self-conscious than what was to come. Not that there’s anything wrong with rarified and self-conscious.

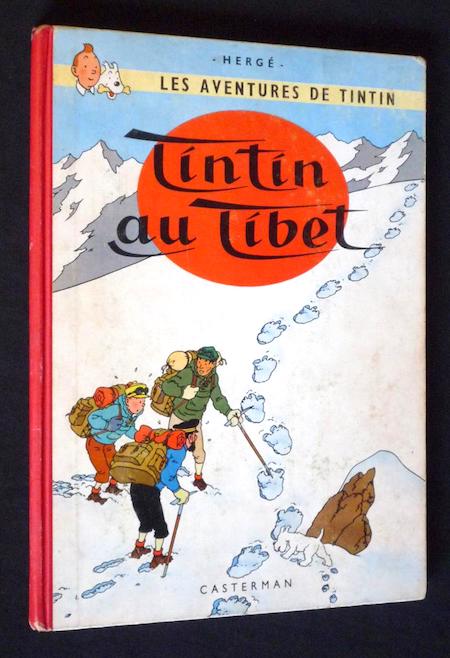

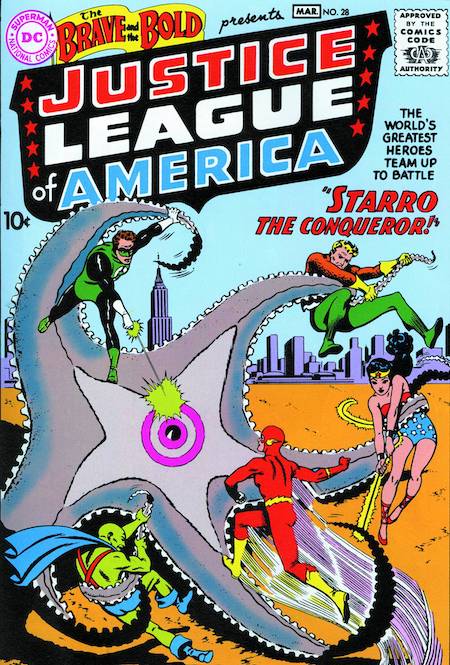

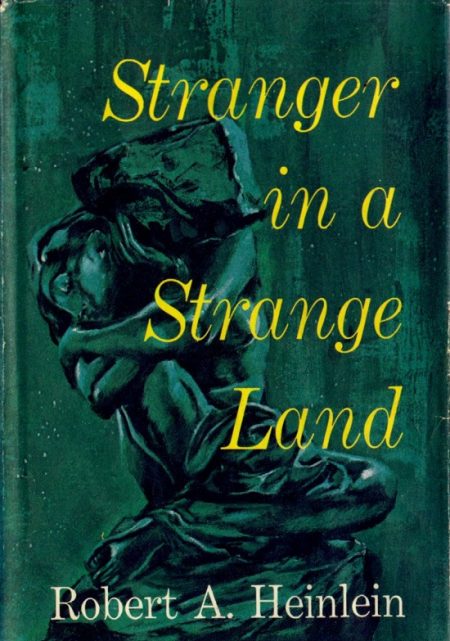

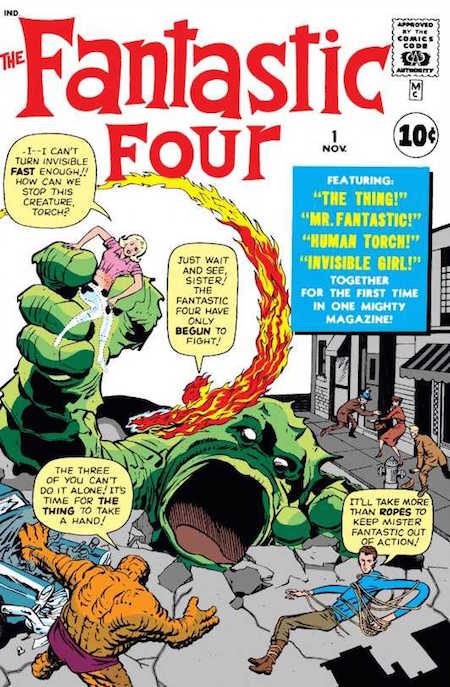

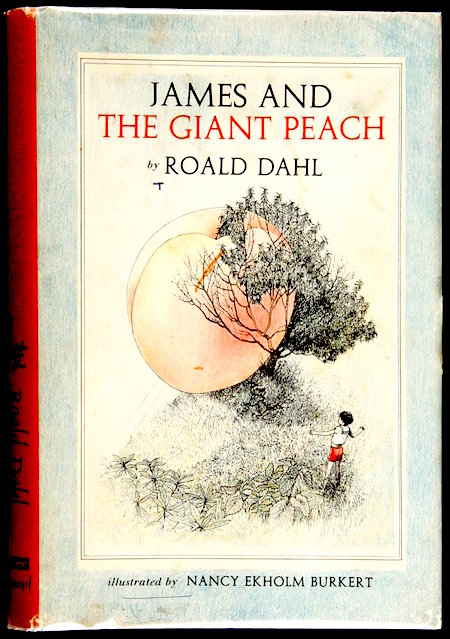

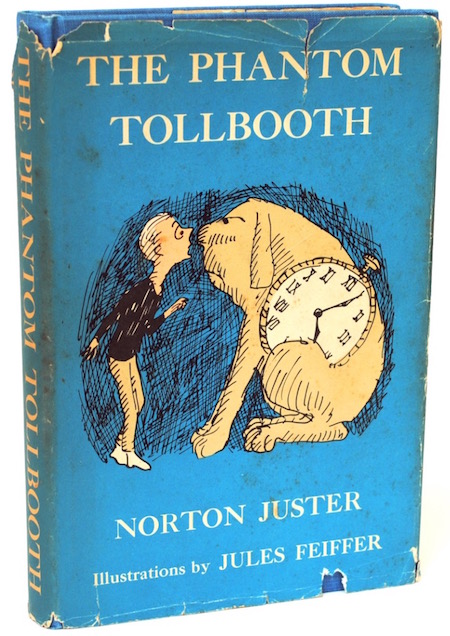

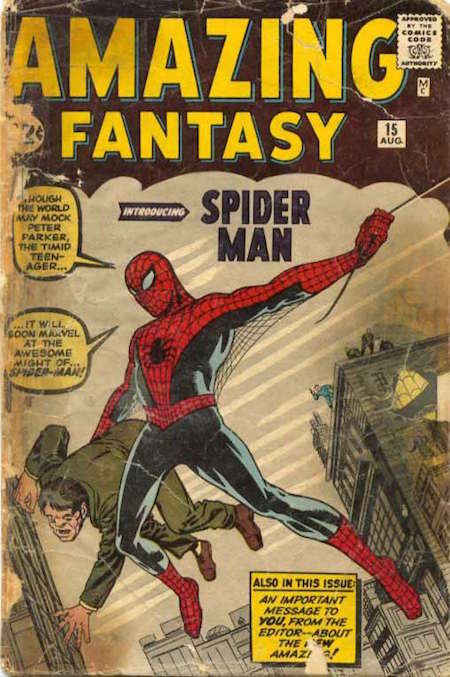

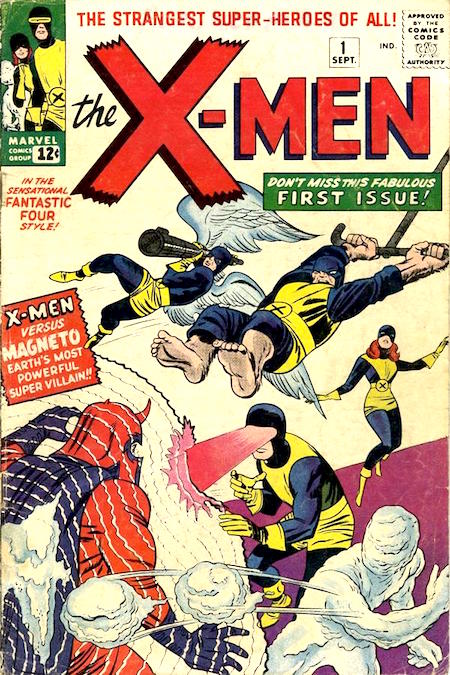

I also want to mention that YA and children’s adventures of this era are incredible! Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon, Hergé’s Tintin in Tibet and The Calculus Affair and The Red Sea Sharks, Goscinny and Uderzo’s Asterix the Gaul, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, C.S. Lewis’s The Horse and His Boy and The Magician’s Nephew, Rosemary Sutcliff’s The Eagle of the Ninth and The Lantern Bearers, Edward Eager’s Knight’s Castle and Half Magic, Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth, Jerome Beatty’s Matthew Looney’s Voyage to the Earth, Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach, Jane Langton’s The Diamond in the Window, Sid Fleischman’s Mr. Mysterious & Company and By the Great Horn Spoon!, Joan Aiken’s The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, Robert Heinlein’s Podkayne of Mars, not to mention the first fruits of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s comic book collaboration: By the time I was growing up, in the 1970s, these were already recognized as timeless classics.

- J.R.R. Tolkien‘s fantasy adventure The Lord of the Rings (w. 1937–1949, p. 1954–1955). Frodo Baggins, an unassuming hobbit, inherits a magical ring from his uncle, Bilbo; their wizard friend, Gandalf, discovers that it’s none other than the One Ring, forged by the Dark Lord Sauron thousands of years ago, and used to corrupt and control the elves, dwarves, and men who wore subsidiary rings of power. Accompanied by his loyal friends Sam, Merry, and Pippin, Frodo carries this terrible artifact to Elrond, one of the most powerful elves remaining in Middle Earth; en route, the hobbits are aided by the immortal Tom Bombadil, and by a mysterious and grim Ranger, Aragorn. Though Frodo is badly wounded by Sauron’s Black Riders, who are on the trail of the ring, the hobbits attend the Council of Elrond. It is decided that the ring must be destroyed by casting it into the fire of Mount Doom, in Sauron’s far-off and foreboding stronghold, Mordor; Frodo reluctantly but courageously volunteers to carry the ring. Accompanying him are his hobbit friends, Aragorn, Gandalf, Gimli the Dwarf, Legolas the Elf, and the human warrior Boromir. Forced to take a perilous path through the Mines of Moria, they are attacked by a host of orcs and an ancient demon; meanwhile, Boromir begins to desire the ring for himself — so Frodo decides to flee the fellowship. Orcs capture Merry and Pippin, and Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas pursue them. Gandalf rouses the King of Rohan to ride to the ancient fortress of Helm’s Deep; tree-people known as Ents lead an attack on the stronghold of a turncoat wizard; Gollum, a twisted hobbit-creature whom we’ve met before, guides Frodo and Sam via secret paths to Mordor… but leads them into the lair of a giant spider. Epic! I’ve written about The Return of the King, the rousing final volume of The Lord of the Rings, elsewhere. Fun facts: This three-part book, which began as a sequel to Tolkien’s 1937 fantasy novel The Hobbit, was the final movement of a larger epic on which the author had worked since 1917; it is probably the most influential work of fantasy of the 20th century. Half of the book was adapted by Ralph Bakshi as a creepy animated movie in 1978; it is now a cult classic. Peter Jackson’s live action adaptations (2001–2003) were a box-office smash.

- Rosemary Sutcliff’s YA Eagle of the Ninth historical adventure The Eagle of the Ninth. The story is set in Roman Britain in the early 2nd century AD. Some years earlier, the Ninth Legion of the Roman Army had marched into northern Britain, bearing a bronze eagle as their standard; they were never seen again. (Sutcliff was inspired to write the story by the disappearance of the Ninth Legion from the historical record following an expedition north to deal with Caledonian tribes in 117.) The son of the Ninth Legion’s commander, Marcus Aquila, who’s grown up to be a soldier, is discharged from the military after being wounded in battle. While recuperating, he forms friendships with Esca, a young Briton whom Marcus purchased as a manservant-slave, an orphaned wolf cub, and Cottia, a British girl being raised as a Roman. Marcus dreams of discovering the truth about the disappearance of the Ninth Legion, and restoring his father’s honor; finally, accompanied by Esca, he disguises himself as a Greek oculist and travels beyond Hadrian’s Wall into Caledonian territory. There, he learns that the titular eagle of the ninth has become a symbol of Roman defeat among the restive tribes along the border. Can he retrieve it? Sutcliff’s writing is gorgeous, the action is thrilling, and we come to care deeply about Marcus and his friends. Fun facts: The Eagle of the Ninth is the first in a sequence of novels tracing the history of a family, of the Roman Empire and then of Britain; these include — in series order — The Silver Branch (1957), The Lantern Bearers (1959), and Sword at Sunset (1963). A 2011 movie adaptation starred Channing Tatum as Marcus Aquila and Jamie Bell as Esca.

- Richard Matheson’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure I Am Legend (1954). Though it has inspired more thrilling novels (Stephen King is a Matheson fan) and movies, I Am Legend is less an adventure than it is a novel of ideas (about the psychology of social isolation), a bleak Robinsonade (set in a vampire-infested Los Angeles of 1976, with no hope of rescue), and a scientific mystery (valorizing painstaking inductive reasoning). What action there is largely occurs in flashbacks — as we learn about the devastating spread of a zombie-ism/vampirism-like pandemic. Even our hero, Robert Neville, is less creative and brilliant than he is merely dogged; and he’s a drunk. Still, there is much to enjoy here. Neville stakes vampires by day, and by night — as the vampires howl outside his door — he attempts to unravel the cause of the plague (are the vampires physically, or just psychologically transformed?), and muses about the overlap between legend and history. Then he meets — and pursues, and captures — Ruth, who might be a survivor of the plague. Or is she something else? Are there non-feral vampires? Is he, himself, a legend? Fun fact: The excellent 1971 science-fiction movie The Omega Man, starring Charlton Heston, is loosely based on I Am Legend. Other movie adaptations have been less entertaining.

- Agatha Christie’s espionage adventure Destination Unknown (US title: So Many Steps to Death. Just before she overdoses on sleeping pills in a Moroccan hotel, Hilary Craven is approached by Jessop, a British secret agent who talks her out of killing herself… and persuades her to instead undertake a dangerous mission, impersonating the wife of a young boffin who’s invented ZE Fusion — and who may have defected to the Soviets. The scientist’s wife was apparently en route to a rendezvous with her husband when her plane to Casablanca crashed; she won’t live long. Hilary’s daughter has died, and her husband has left her — so why not, she figures. Heading to a secret scientific research facility in the Atlas Mountains, which is disguised as a medical research center, she meets a Hitchcockian-esque assortment of characters, none of whom can be trusted to actually be who they claim to be. (One of them, a handsome young American, is particularly compelling.) Hilary’s putative husband is indeed at the facility — which turns out not to be a Soviet operation, after all. With the help of clues that Hilary has left behind, Jessop pursues her to the facility. An ingenious escape plan is concocted, but is it too late? Destination Unknown asks us to grapple with questions — is pure scientific research immoral, if it could lead to death and destruction? should the younger generation use its energy to overthrow accumulated wealth and prestige? — less vexing, perhaps, to earlier and later readers. I prefer the absurdity of Michael Innes’s Operation Pax (1951), but this is fun stuff. Fun facts: Christie was writing in the wake of the Fuchs/Pontecorvo affairs. In 1950, Klaus Fuchs, a German theoretical physicist who’d worked on the Manhattan Project during WWII, was arrested for espionage; it seems he’d been supplying information to the Soviet Union. Bruno Pontecorvo, an Italian nuclear physicist who’d worked with Fuchs after the war at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, England, defected to the Soviet Union that same year.

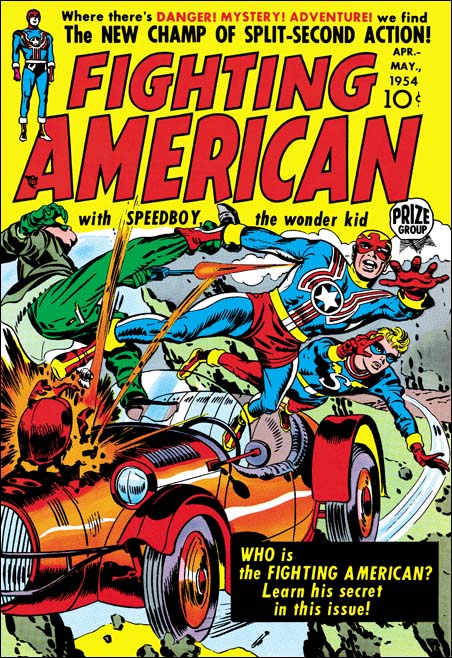

- Joe Simon and Jack Kirby‘s Fighting American comic (1954–1955). When Joe Simon and Jack Kirby created Fighting American, first published by Prize Publications, they did so as a gag; note that Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood‘s “Superduperman” had appeared in MAD Magazine the previous year. What makes this comic so interesting and enjoyable to read is the fact that Simon and Kirby were parodying their own creation. Back in 1941, they’d introduced Captain America to the American public with a first-issue cover on which the titular patriotic supersoldier punches Hitler in the face. Captain America, which became a best-selling title for Timely (eventually, Marvel), helped revolutionize the comic-book layout with dynamic action splashed across full and sometimes double pages. In the years following WWII, Simon and Kirby’s studio would crank out all sorts of titles — romance, crime, western, sci-fi, war — but superhero comics were on the wane. Fighting American is an absurdist effort: Our hero’s alter ego is Johnny Flag, a McCarthy-esque TV commentator who denounces Communist supporters; weirdly, his true identity is the unathletic younger brother of the dead Johnny. His enemies have monikers like Poison Ivan, Deadly Dolittle, Invisible Irving, and the Sneak Of Araby; his sidekick is Speedboy. But the action is truly spectacular — much more so than Simon and Kirby’s work on Captain America. It’s as though the pioneering comics duo was demonstrating what superhero comics could become; in 1961–1963, when Kirby and Stan Lee co-created The Fantastic Four, The Avengers, et al., everybody else finally got the message. Fun facts: In 1966, Simon packaged a single issue of Fighting American consisting of reprints and unpublished material, for Harvey Comics. The 2010 collection Simon and Kirby: Superheroes, a gorgeous doorstopper from Titan Books, is probably the best source for Fighting American‘s original run.

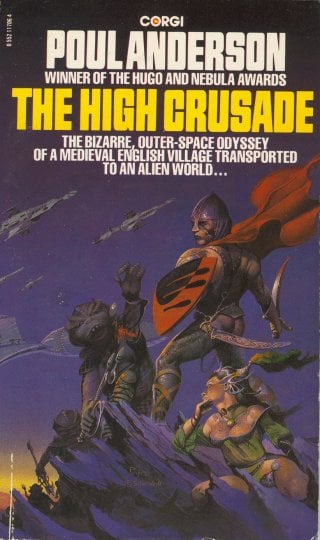

- Poul Anderson’s fantasy adventure The Broken Sword. In the 11th century, when the Danes held sway over northern and eastern England, but the “White Christ” as the Vikings called Jesus) was threatening the power of the Norse, English, and Irish gods, Skafloc, son of the half-Christian Viking chieftan Orm the Strong, is kidnapped and raised by elves; in his place, the elves leave a troll-born changeling called Valgard. Alfheim, homeland of the elves, trolls, sprites, sidhe, goblins, etc., is everywhere apparent… but as Christianity spreads, Alfheim is diminishing, vanishing. Meanwhile, a troll army is massing to destroy Alfheim forever. The Norse gods, engaged in a war with the Frost Giants, set the story in motion thanks to their strategic maneuvers. Skafloc, who grows up to be a warrior and wielder of elf magic, is presented with a broken iron sword; a gift of the Norse gods, it can only be repaired by the frost giant Bolverk. Valgard, meanwhile, grows up to be a brutish Viking berserker; when he discovers the truth of his own origins, he joins the trolls. Anderson, whose Hrolf Kraki’s Saga (1973) would retell Danish sagas, remains true to Norse stories of heroic achievement: the action is brutal, everybody loses. Fun facts: Reviewers of The Broken Sword often note the similarities between its plot and that of The Lord of the Rings, published the same year. Both Anderson and Tolkien mined “the Northern thing” as they developed their own modern versions of epic fantasy; Anderson’s version was less hopeful, and less successful. Michael Moorcock declared The Broken Sword the superior effort, and noted its influence on his Elric saga.

- C.S. Lewis’s Narnia fantasy adventure The Horse and His Boy. During the reign of the four Pevensie children as kings and queens of Narnia, two Narnian talking horses, Bree and Hwin, both of whom were stolen by the Calormenes as foals, escape from Calormen — a Middle Eastern-esque country to the southeast of Narnia, and separated from it by the country of Archenland and a large desert — and head home. Riding Bree is an orphan named Shasta, who wants to avoid being sold into slavery; riding Hwin is Aravis, a young Calormene aristocrat, who is running away to avoid being forced to marry Calormen’s vizier. The group passes through Calormen’s capital city, Tashbaan, where they learn of the ruler’s plan to invade Archenland and raid Narnia; they also encounter Narnian visitors who mistake Shasta for an Archenland prince to whom he bears a striking resemblance. They flee into the desert, heading for “Narnia and the North!” Along the way, they encounter vicissitudes which turn out to have been blessings in disguise orchestrated by Aslan; this is Lewis’s religious message. Will they warn Archenland of the invasion in time? And will Shasta discover his true identity? Fun facts: Of the seven novels that comprise The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–1956), The Horse and His Boy was the fourth to be written and the fifth to be published; according to the series’ internal chronology, however, it is the third book. It’s the only series installment to take place entirely within Narnia.

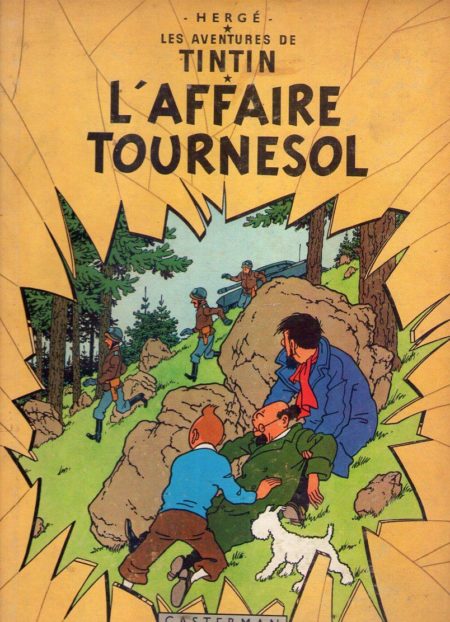

- Hergé’s Tintin adventure L’Affaire Tournesol (The Calculus Affair, 1954–56; as an album, 1956). Glass and porcelain items at Marlinspike Hall begin to shatter inexplicably; the next day, Professor Calculus leaves for Geneva to attend a scientific conference. Tintin and Haddock follow him there, only to be run off the road into Lake Geneva… then nearly blown up! We discover that intelligence agents from Syldavia and Borduria — the fictional Balkan nations we’ve already visited in King Ottokar’s Sceptre and Destination Moon — are seeking to obtain an ultrasonic device, capable of being used as a weapon of mass destruction, which Calculus has recently developed. This is espionage thriller along the lines of Ambler’s The Dark Frontier or Cause for Alarm, say, or — closer to home — Edgar P. Jacobs’s Blake and Mortimer comic Le Secret de l’Espadon (1946–1949), and it’s a fun ride. Tintin and Haddock remain one step behind as Calculus is kidnapped by first Bordurians, then Slydavians, then Bordurians again; when they arrive in Borduria’s capital, Szohôd, they’re monitored by Colonel Sponsz’s secret police. Meanwhile, back in Marlinspike, for comic relief, insurance agent Jolyon Wagg and his family move in for a holiday. Will Tintin and Haddock rescue Calculus, and get him home? Fun facts: The 18th Tintin adventure was serialized in Belgium’s Tintin magazine. Hergé’s depiction of Borduria was based on Eastern Bloc countries; Hergé named the country’s leader Plekszy-Gladz, a pun on Plexiglas, although the comic’s English translators renamed him Kûrvi-Tasch, a mustache joke.

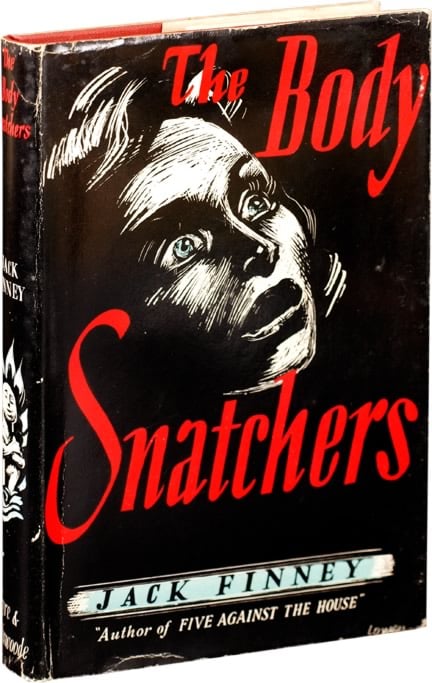

- Jack Finney’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure The Body Snatchers (1954; as a book, 1955). Why, wonders psychologist Miles Bennell, are so many of his patients — in bucolic Mill Valley, California — suddenly convinced that their loved ones aren’t really who they’re supposed to be? These doppelgängers, according to their spouses, relatives, colleagues, and friends, look exactly like the people they’ve replaced; they share their victims’ memories and mannerisms. But they’re not them! A case of mass hysteria, Bennell decides… until he discovers a curiously “blank” body, without features or fingerprints, concealed in a basement cupboard. He and his ex-girlfriend, along with others convinced that something uncanny is going on, begin to wonder whether there is an alien invasion going on. And if so, who can they trust? The aliens — and the science behind how they operate — aren’t particularly believable… but the dramatic tension is incredible. How much evidence of the impossible is required until we see the truth? Fun fact: Serialized in Colliers in 1954. (Philip K. Dick’s pod-people story, “The Father-thing,” was published a few months later.) Memorably adapted as a movie in 1956, by director Don Siegel; and again in 1978, by director Philip Kaufman — with an extraordinary cast that includes Donald Sutherland, Brooke Adams, Veronica Cartwright, Jeff Goldblum, and Leonard Nimoy.

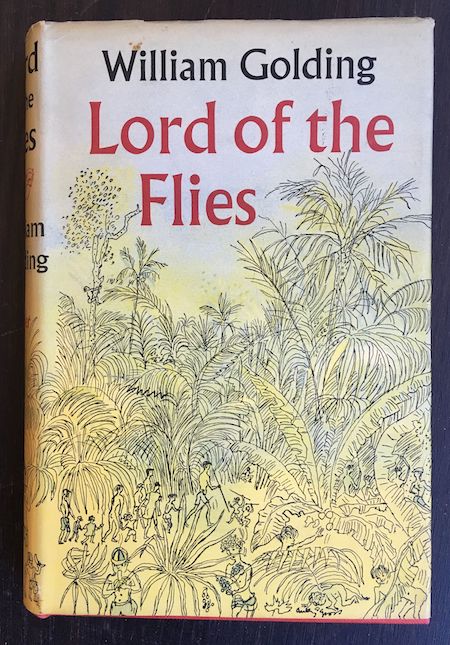

- William Golding’s sardonic Robinsonade Lord of the Flies. In the midst of a wartime evacuation, a British airplane carrying boys in their middle childhood or preadolescence crashes near an uninhabited island in a remote region of the Pacific. Ralph and an overweight, bespectacled boy nicknamed “Piggy” convene all the survivors; among them are the members of a boys’ choir, led by the red-headed Jack. Ralph establishes a policy of having fun, surviving, and maintaining a smoke signal that could alert passing ships to their presence; Jack, whose choirboys become the group’s hunters, and a semi-epileptic boy named Simon become Ralph’s lieutenants. Poor Piggy, whose glasses are used to start a fire, becomes a laughing-stock. When Jack lures the signal fire crew away for a hunt, a ship passes the island without rescuing them; this leads to a rift between Ralph and Jack. Meanwhile, when Simon encounters a pig’s head that the hunters have mounted on a stake, he conducts an imaginary dialogue with the “Lord of the Flies,” which warns him that the increasingly savage hunters and their breakaway tribe will kill him. Things rapidly get worse, and soon Ralph is fleeing for his life through the forest, worried that his own head will end up on a stake! Fun facts: Lord of the Flies, Golding’s first novel, which is to the 1858 young castaway’s novel The Coral Island what The Borribles is to Elisabeth Beresford’s Wombles books, became a bestseller — and has been called one of the best English-language novels of all time. It has been adapted more than once for the screen, but never successfully.

Note that 1955 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Fifties. The transition away from the previous era (the Forties) begins to gain steam….

The years 1953 and 1954 were cusp years between the eras we think of as the Nineteen-Forties and Fifties; by ’55 the Fifties were fully underway, building steam as the era headed towards its 1958–1959 apex. In the best adventure novels of 1955, we find few relics of the Forties.

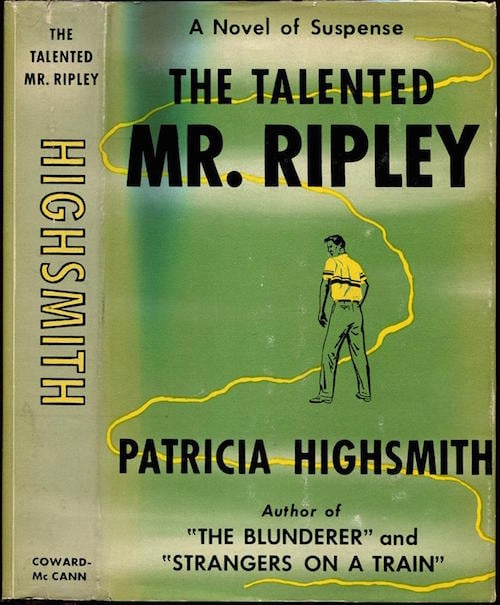

- Patricia Highsmith’s crime adventure The Talented Mr. Ripley. Having accepted a millionaire’s request to bring his footloose son, Dickie, back to New York from Italy, Tom Ripley becomes obsessed with Dickie’s upper-class mannerisms and lifestyle. One thing leads to another, and [SPOILER] he murders Dickie and assumes his identity. This is the first in a popular series of Ripley novels. It was adapted for the screen in 1960 (with Alain Delon), and again in 1999 (with Matt Damon).

- Graham Greene’s espionage adventure The Quiet American. A sardonic inversion of the genre in which the titular undercover CIA agent, Alden Pyle, is an obtuse idealist. When innocent civilians are killed by a car bomb, a cynical British war correspondent realizes that Pyle — who is working to achieve a synthesis of Communism and colonialism in Vietnam — was indirectly responsible for it. So he decides to take part in Pyle’s assassination. The book, which outraged American readers at the time, was adapted for the screen in 1958 by Joseph L. Mankiewicz; Audie Murphy played Pyle.

- J.P. Donleavy’s picaresque The Ginger Man. An adventure in a kiss kiss rather than a bang bang way, Donleavy’s first novel — told from various perspectives — is funny, horrifying, scandalous. Sebastian Dangerfield, an impecunious American attending law school in Dublin while supporting a wife and child, staggers from incident to incident — in search of bacon and eggs, mostly, but also casual sex. Which, in Ireland, in the 1940s, was a rare commodity indeed. The novel was published as part of Olympia Press’s pornographic Traveller’s Companion Series, and banned in both Ireland and the United States for obscenity.

- Lionel White’s crime adventure The Big Caper. Perhaps best remembered today as the inspiration for the 1957 film noir (starring Rory Calhoun) of the same title, White’s bank-job novel gave the crime genre’s “caper” subcategory its moniker. Flood, a criminal mastermind, puts together a team — including an arsonist, a dynamite artist, and some muscle — to rob a bank in a Florida beach town. Key to Flood’s big caper are Frank and Kay, neither of whom are criminals, but both of whom owe Flood a big favor; it is their job to move to the town and pretend to be a couple. The trouble begins when Frank and Kay actually fall in love….

- J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy adventure The Return of the King. This is — as we’re all required to know, now — the third and final volume of The Lord of the Rings. The wizard Gandalf and the halfling Pippin ride into Minas Tirith, whose steward blames them for his son Boromir’s death. King Théoden and the Riders of Rohan hasten there as well, because the city is about to be besieged by the approaching armies of Mordor. The ranger Aragorn, the elf Legolas, and the dwarf Gimli travel through the haunted Paths of the Dead. Meanwhile, the halflings Frodo and Sam must escape from their orc captors and sneak through Mordor, smuggling the One Ring to Mount Doom under the baleful eye — and influence — of Sauron himself. And that’s just how this book begins.

- Crockett Johnson’s dream adventure Harold and the Purple Crayon. Four-year-old Harold wants to go for a walk, so he used a purple crayon to draw a path… One adventure leads to another, until Harold draws himself home again. Johnson, who created the excellent 1940s comic strip Barnaby for the left-wing newspaper P.M., here hints at the imagination’s too-seldom tapped anarchic possibility… in the least didactic, most delightful manner possible. The first book in a series that would include Harold’s Fairy Tale (1956), Harold’s Trip to the Sky (1957), Harold at the North Pole (1958), and Harold’s Circus (1959).

- Jim Thompson’s crime adventure After Dark, My Sweet. On the lam from a mental institution, William Collins, an ex-boxer with one screw loose, tries to go straight. Alas for him, he meets up with a sexy dame and a smooth-talking con artist who embroil him in a kidnapping scheme. Which goes terribly wrong… because the child he snatches is not only the wrong victim, but a diabetic who may die without insulin. The 16th novel from this prolific, sometimes lyrical, sometimes bonkers pulp crime writer, and — with A Hell of a Woman, published the year before, and his earlier books The Killer Inside Me and Savage Night — one of his best.

- John Wyndham’s science fiction adventure The Chrysalids (US title: Re-Birth). In a far-future, post-Tribulation England whose inhabitants zealously persecute mutated humans (“Blasphemies”), 10-year-old David must keep his burgeoning telepathic abilities to himself. Eventually, he and his fellow telepaths are discovered… so they flee to the Fringes, where they encounter mutants scraping by in a primitive fashion. However, David’s younger sister, Petra, claims that she’s been contacted by telepaths from an advanced, utopian society in distant “Sealand” (New Zealand?). Can they make it there?

- C.S. Lewis’s Narnia fantasy adventure The Magician’s Nephew. The sixth of the seven Narnia novels, The Magician’s Nephew is a prequel to the series — which is why today’s readers are often encouraged to read it first. (Of course they should read it sixth, as the author intended.) Here we witness Aslan’s creation of the Narnia world, a millennium before the events of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe; and we witness the introduction, into Narnia, of such previously unexplained factors as the White Witch, a human king and queen (in a world of talking beasts), even the lamp-post. In a way, it’s a science fiction story — the rings are a technology that permit you to roam the multiverse — but never mind that.

- Michael Innes’s Cold War suspense-pursuit adventure The Man from the Sea (aka Death by Moonlight). A romantic assignation on a beach in Scotland, between Richard Cranston and Lady Blair, is interrupted by a man who emerges from the sea: John Day, a nuclear physicist who’d defected to the Soviet Union. Day claims that he wants to see his wife again, before he dies… and Cranston agrees to help him elude both British authorities and Soviet agents. But is Day telling the truth? A knowing — sometimes tongue-in-cheek — homage to John Buchan‘s The Thirty Nine Steps.

- Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination (also published as Tiger! Tiger!, serialized 1956; in book form, 1957). If Heinlein’s Double Star, also published in 1956, is The Prisoner of Zenda in space, then The Stars My Destination is a proto-psychedelic sci-fi version of The Count of Monte Cristo. In the 25th century, personal teleportation — known as “jaunting” — has thrown the solar system’s social and economic order into chaos. During a war between the inner planets and the outer satellites, the Nomad, a merchant spaceship, is destroyed; the only survivor, a directionless loser named Gully Foyle, is cast adrift. He repairs the Nomad, and returns to Terra, though not before he’s captured by a cargo cult who tattoos his face with a tiger mask. He embarks on a life of violent crime, eventually transforming himself into the elegant Geoffrey Fourmyle — all the while seeking revenge on the captain of another merchant ship, the Vorga, who’d ignored his distress signal when he was marooned. Meanwhile, we learn that the Nomad had been carrying “PyrE”, a telepathy-triggered explosive that could mean the end of humanity. Fun fact: Originally serialized in Galaxy magazine, Bester’s novel — with its dark vision of powerful megacorporations, and the cybernetic enhancement of the body — is a precursor of cyberpunk.

- Edward Eager’s YA fantasy adventure Knight’s Castle. The second installment in Eager’s famous Magic series is my favorite. Sent to stay with their more sophisticated cousins, Eliza and Jack, Roger and Ann are delighted with a toy castle play set they’re given. After they see the movie Ivanhoe (released in 1952, it stars Robert Taylor as Sir Wilfred of Ivanhoe, Elizabeth Taylor as Rebecca, Joan Fontaine as Rowena, and George Sanders as Sir Brian De Bois-Guilbert), the four children use the castle set to play an elaborate imaginative game riffing on Ivanhoe — one in which not everything goes the way it does in Walter Scott’s tale. At night, on several occasions, the cousins find themselves transported into the world they’ve created… where they must set things straight. (The original LARP?) As with all of Eager’s Magic books, the trick is figuring out the rules by which this magical alternate reality is governed. Fun fact: The other titles in this series include Half Magic (1954), Magic By the Lake (1957), The Time Garden (1958), Magic Or Not? (1959), The Well-Wishers (1960), and Seven-Day Magic (1962). Eager was a huge fan of E. Nesbit’s magical adventures, and pays tribute to Nesbit here.

- Robert Heinlein’s sci-fi adventure Double Star. Lawrence “The Great Lorenzo” Smith is a brilliant mimic… but he’s down on his luck. So when he’s approached by aides to John Joseph Bonforte, one of the most prominent politicians in the solar system, about impersonating Bonforte — who’s been kidnapped by his opponents on the eve of a general election — he agrees, even though he’s a Martianphobe who disagrees with Bonforte’s campaign to enfranchise Mars. Yes, this is The Prisoner of Zenda in space; hokey material, but Heinlein handles it very well. Smith must first fool Martians, during a fraught ceremony via which Bonforte is adopted into a Martian tribe; and that’s the easy part. Once it becomes apparent that Bonforte won’t be able to appear in public for some time, Smith must learn Bonforte’s mannerisms and background story, and fool the solar system’s Emperor. Political conspiracies, diplomatic maneuvers — it’s not Starship Troopers, but it’s just as exciting. Fun fact: Serialized in Astounding Science Fiction and published in hardcover the same year. Double Star was awarded the 1956 Hugo Award for Best Novel — the author’s first.

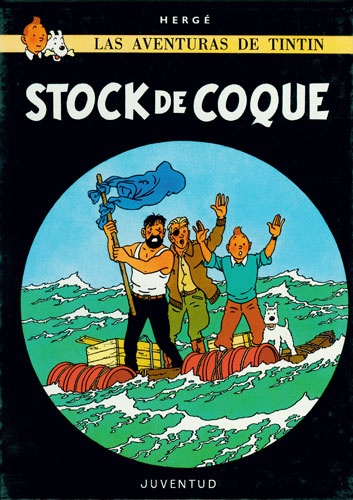

- Hergé’s Tintin adventure Coke en stock (The Red Sea Sharks, serialized 1956–1958; as an album, 1958). When Abdullah, the terrifyingly naughty son of Mohammed Ben Kalish Ezab, the Emir of Khemed, turns up at Marlinspike, because his father has been overthrown by Sheikh Bab El Ehr, Tintin and Haddock decide to help restore the Emir to his throne. Flying to the Middle East, however, they narrowly escape being blown up. Then, as they ride on horseback to the Emir’s hideout, armoured cars and fighter planes — sent by “Mull Pasha”, who is actually Tintin’s old nemesis, Dr. Müller — are sent to intercept them. Eventually, Tintin and Haddock learn that Sheikh Bab El Ehr is backed by an oddly familiar businessman, the Marquis di Gorgonzola, who offers transport to African Muslims on the pilgrimage to Mecca… and then sells them into slavery. (Khemed is a key part of Gorgonzola’s scheme.) En route to Mecca, their sambuk is attacked by fighter planes; they shoot one down, and rescue its pilot — Piotr Skut, an Estonian mercenary. All of which is just a build-up to their discovery of a shipload of slaves! Fun fact: Hergé developed the plot for The Red Sea Sharks after reading a piece of investigative journalism about the continuing existence of the slave trade within the Arab world.

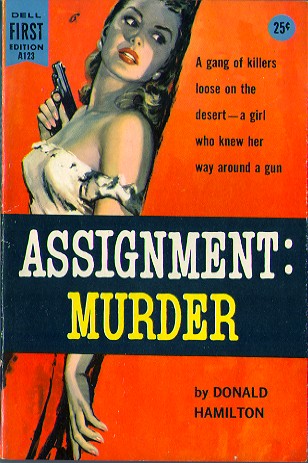

- Donald Hamilton’s espionage adventure Assassins Have Starry Eyes (also known as Assignment: Murder). Before striking gold with his Matt Helm series, Hamilton wrote a couple of thrillers in the mold of Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps and Household’s Rogue Male — that is, they feature highly competent but essentially nonviolent protagonists who unwillingly find themselves involved in assassination plots. Here, James “Greg” Gregory, a Los Alamos mathematician, is shot while out hunting. While recovering in the hospital, another attempt is made on his life — by the would-be assassin’s fiancée, Nina. When another scientist is killed, and Greg’s estranged wife goes missing, he heads into the New Mexico wilderness, allowing himself to be captured. Greg and Nina wind up working together… against domestic saboteurs, traitors, and other villains. Fun fact: Anthony Boucher called Hamilton’s spy thrillers “as compelling, and probably as close to the sordid truth of espionage, as any now being told.”

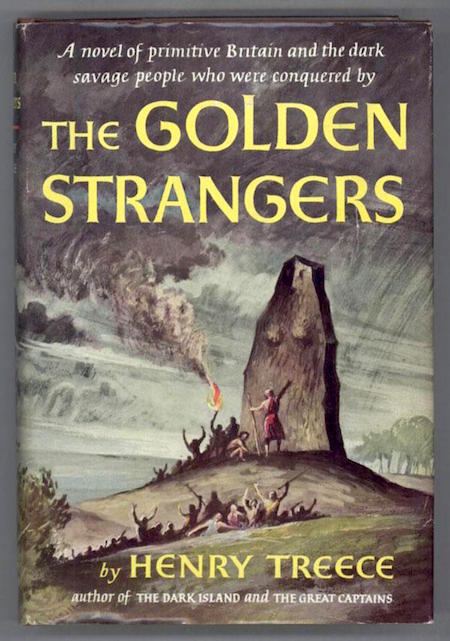

- Henry Treece’s pre-historical adventure The Golden Strangers. Garroch, chieftain of a primitive, flint-using tribe of Britons, does his part to sustain the “Barley Dream,” a web of ritual and human sacrifice without which his tribe’s crops cannot not be made to grow. When the golden strangers — fair-haired Celts, from the continent, bearing metal weapons — attempt to invade, Garroch kills their leader and takes his daughter, Isca, as his bride. Or is Isca, a woman to be reckoned with, manipulating him for purposes of her own? Whose gods, and way of life, will triumph? Rosemary Sutcliff, whose Matter of Britain novels are better remembered today than Treece’s, called this “one of the best as well as one of the strangest historical novels I have ever met.” Indeed, Treece’s short epic combines superstition, magic, and brutal violence; it’s both realistic and fantastical. Fun fact: First title in Treece’s Celtic Tetralogy. Treece is best known today for his juvenile historical novels, particularly those set in the Viking age. His other 1956 novel, The Great Captains, is one of the more original retellings of the Arthurian mythos.

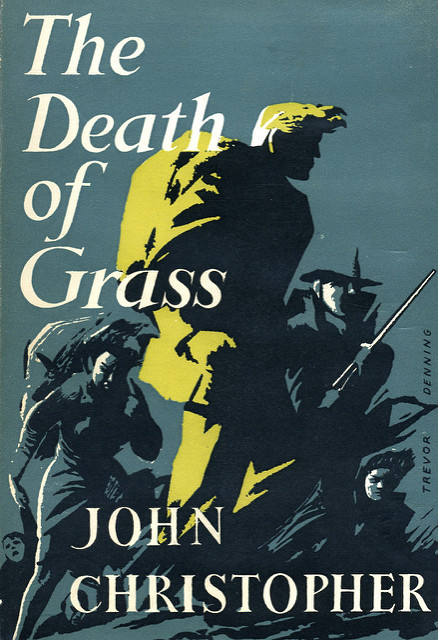

- John Christopher’s post-apocalyptic adventure The Death of Grass. In this updating of J.J. Connington’s Radium Age eco-catastrophe Nordenholt’s Million, a plant virus infects the staple crops of West Asia and Europe such as wheat and barley — that is, all of the grasses. Which kills off the cattle, as well. At first, England prides itself on how well-disciplined its response to the crisis is, compared with that of Asian nations… but all too soon the British government resorts to martial law mass executions, and then it’s anarchy. With their families in tow, John Custance and his friend, Roger Buckley, make their way across a savage, chaotic England. They aim to reach the safety of John’s brother’s potato farm in an isolated northwestern valley — where they’ll survive on potatoes, beetroots and fresh water — and along the way, they gather an entourage of others seeking sanctuary. Day by day, however, the group’s civilized moral code decays. When they reach the heavily defended farm, and John’s brother’s won’t allow the whole group to stay there, what will they do? Fun fact: John Christopher (Sam Youd)’s second novel; published in the United States the following year as No Blade of Grass. It was adapted, under that title, as a 1970 British-American science fiction movie directed by Cornel Wilde.

- Hammond Innes’s sea-going adventure The Wreck of the Mary Deare. When salvager John Sands boards an enormous, rusty and leaking freighter — the Mary Deare — which has been set afire, and abandoned by its crew in a dangerous section of the English Channel, he discovers the ship’s first officer, Gideon Patch, trying to run the ship on his own. The harsh, exhausted, half-crazed Patch has stayed aboard, or so he claims, in order to prove that the ship was deliberately sabotaged, by its owners, in order to collect insurance on cargo that had secretly been off-loaded at Rangoon. (What was loaded into the holds, and why did the captain first appear covered in coal dust?) Patch needs help running the ship aground on rocks to the south of the Channel Islands. Although doing so will void his salvage claim, and although Sands decides to help. When they return to London, Patch is brought before a board of inquiry to determine what happened. Finally, there’s a race to return to the ship, in order to prevent the ship’s owners from destroying the evidence of their fraud. Fun fact: The novel was adapted in 1959 as a movie of the same title, starring Charlton Heston as Sands and Gary Cooper as Patch; Michael Anderson directed. Thriller author Eric Ambler wrote the screenplay.

- Arthur C. Clarke’s sci-fi adventure The City and the Stars. A Stapledonian epic, which illustrated two points important to the author: our curiosity about the world/universe is what makes us human; and organized religion retards humankind’s progress. In Diaspar, a billion-year-old, self-sufficient domed city located on Earth, Alvin is a “Unique.” Despite living in a utopian, perfectly regulated social order (run by a super-computer), in which human consciousnesses can be downloaded into new bodies, and are therefore immortal; and despite having been raised in a culture that encourages incuriosity and terror about the outside world, he dreams of exploration. Once he finally escapes Diaspar, Alvin’s curiosity is richly rewarded. Elsewhere on Earth, he finds another city-state — Lys — that is less reliant on technology, and whose citizens are telepaths. He discovers that Earthlings once traveled the stars, only to be forced back to their planet by aliens; and once offworld, Alvin discovers civilizations and entities that beggar belief. Will he keep going? Or return to Diaspar, as a prophet? Fun fact: We’ve seen sci-fi dramatizations of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave before, for example in Gabriel De Tarde’s 1884 novella Underground Man; and the meme appears frequently in YA sci-fi novels of the Sixties and Seventies. Clarke’s imagination regarding future technologies, however — which we’d now recognize as, for example, 3D printing, wireless communication and energy transfer, and genetic engineering — is truly original and far-out.

- Ed McBain’s crime adventure Cop Hater. In the first installment in McBain’s long-running (~50 titles, over as many years) 87th Precinct series, detectives Steve Carella and Hank Bush respond to reports of a shooting, only to discover one of their own dead on the street. Soon, another detective is killed… and then, Bush too. Though he’s no genius, Carella figures out who’s behind all this: a cop hater! So in his persistent way, he does what it takes to catch the perp. Set in an unnamed, but New York-like city, Cop Hater would provide a template for future police procedurals, including cop shows like Hill Street Blues — which McBain furiously condemned as a ripoff. (Carella also reminds me of another not-bright, but streetwise and unflagging, fictional New Yorker: Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s Ben Grimm, aka The Thing. For one thing, both of them are married to beautiful disabled women, in Carella’s case the deaf-mute Teddy.) Here, we don’t find the romance of postwar detective fiction… just the flop sweat and flat feet of ordinary cops doing their jobs. Fun fact: The author, Evan Hunter (also not his birth name), wrote the 1954 bestseller Blackboard Jungle; and he would go on to write the screenplay for Hitchcock’s 1963 film The Birds. Akira Kurosawa’s terrific 1963 police procedural, High and Low, was loosely based on McBain’s 1959 novel King’s Ransom.

- 1957. Alistair MacLean’s WWII commando adventure The Guns of Navarone. This was one of my favorite adventure novels, when I was a teenager; I’ve included it on my list of the 200 Greatest Adventure Novels of All Time. New Zealand mountaineer Keith Mallory, American demolitions expert Dusty Miller, Greek resistance fighter Andrea, and two other commandos — a particularly satisfying example of the Argonaut Folly’s “crackerjack” sub-genre — are sent on a mission impossible. They must destroy an impregnable German fortress (on the fictitious Greek island of Navarone) that threatens Allied ships racing to the rescue of British soldiers trapped in the Aegean! Cliffs are scaled, storms are weathered, gun fights blaze — and if all this weren’t enough, there’s a trademark MacLean plot twist or three. Who among the commandos is a double agent? And which double agent is triple agent? Fun fact: Adapted as a perfectly good 1961 movie starring Gregory Peck, David Niven, and Anthony Quinn; MacLean’s 1968 followup, Force 10 from Navarone, is a sequel to the movie, not the book. FWIW, the excellent 1965 song “The Guns of Navarone,” adapted from the movie’s theme by The Skatalites, is the best-selling ska single ever.

- Nevil Shute’s On the Beach (1957). In the near future of 1963, nuclear fallout from World War III has eradicated all human and animal life in the Northern Hemisphere, and air currents are steadily carrying the same fate to the Southern Hemisphere. Only South Africa, and the southern parts of South America and Australia are still habitable… our story takes place in Melbourne. One of the last US nuclear submarines, captained by Commander Dwight Towers, is preparing to head from Melbourne to America’s west coast — because an incomprehensible Morse code signal has been received. (Perhaps someone is still alive?) Towers is attracted to a young Australian woman, Moira Davidson, but remains loyal to his family back home… even though they must certainly be dead. Moira, meanwhile, copes by drinking heavily. Peter Holmes, an Australian scientist, cannot persuade his wife to believe in the impending disaster. Another member of the submarine crew, Osborne, spends all of his time driving a racecar. As the radiation reaches Melbourne, how will each character face his or her final moments? Fun fact: Originally serialized in the London weekly periodical Sunday Graphic (April 1957). In 1959, the novel was adapted as a film starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, and Fred Astaire. The novel’s title refers to a beach in Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men.”

- Chester Himes’s crime adventure For Love of Imabelle (aka A Rage in Harlem). In the first of the author’s nine “Harlem Detective” novels featuring black police detectives Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones, a hard-working, charch-going undertaker’s assistant (Jackson) is conned out of money that he stole from his employer by the beautiful Imabelle — who immediately takes a powder. Unwilling to believe the worst of her, Jackson enlists the help of his twin brother, Goldy, a con artist and heroin addict who masquerades as a nun (!), and seeks Imabelle across the length and breadth of Harlem. There are shootings, stabbings, and acid flinging; and some great chase scenes. Coffin and Gravedigger, who play much more central roles in later installments of this series, play only a minor role in this one. Fun fact: Chester Himes spent eight years in prison for armed robbery, as a young man; in middle age, he moved to Paris and rubbed elbows with Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Ishmael Reed, and other expats. The author of more literary works such as If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945), he wrote the “Harlem Detective” books in order to make a quick buck.

- John Wyndham’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure The Midwich Cuckoos. An unidentified silver object appears in the center of the (literally) sleepy English village of Midwich; and its population is rendered insensible. A few months later, it becomes apparent that every fertile woman in the village became pregnant during what they now call the “Dayout.” Thirty-one boys and thirty girls are born to Midwich. Their eyes are golden, their skin so pale its silvery. As the Children (as they’re known) grow up, they display telepathic capabilities and an ability to control others’ actions — particularly when anyone threatens them physically. We learn that the same phenomenon has happened in several other villages around the world; but only the English, it sees, are so compassionate that they’re willing to raise what appears to be a hostile mutant or alien species. When the Children’s teacher determined to destroy them, will he succeed? Fun fact: Adapted as Village of the Damned in 1960; there was also a 1995 remake — one of John Carpenter’s weaker efforts.

- Philip K. Dick’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure The Cosmic Puppets. On a visit, with his wife, to his hometown — sleepy, isolated Millgate, Virginia — Ted Barton discovers that you can’t go home again. (Because your hometown is different in important particulars than you remember — shops, parks, even people no longer exist — and apparently, it always already was different. Also, a child with your name died in that town, years ago.) What’s going on? Has the town been caught up in an illusion — or are Ted’s memories false ones? Why does the town drunk remember the town the way Ted does? Who are the incorporeal Wanderers haunting the town? And why can’t Ted escape from Millgate? Although he struggles to make sense of these eerie incongruities, before long Ted finds himself in the midst of a cosmic struggle stretching far beyond Virginia or even Earth. SPOILER: The Zoroastrian demigods Ohrmuzd and Ahriman might have something to do with all this. Is Ted… a messiah figure? Stranger things, indeed. Fun fact: The novel is a revision of Dick’s 1956 story “A Glass of Darkness,” which appeared in Satellite Science Fiction. The title refers to a Bible passage (First Corinthians 13:12) which the author would deploy again, for perhaps his best novel: A Scanner Darkly.

- Jack Kerouac‘s picaresque On the Road. An inspired midcentury installment in the most romantic of Adventure sub-genres, the protagonists of which seek a passionate life not afforded by an enlightened, modern, rationalized social order. Kerouac’s On the Road, which was completed in 1951 — that is, during the Forties (1944–1953) — is a fictionalized account of the author’s American wanderings. Though not a thriller, plot-wise, it’s plenty exciting. Jazz! Poetry! Drugs! Sal Paradise makes his way from New York to Denver, where he falls under th spell of the free-spirited hustler Dean Moriarty, then continues on to San Francisco, down to Mexico, and back to New York. Later, Sal and Dean drive to New Orleans, then back to San Francisco — in search of kicks and a religious-isn exaltation which Kerouac was among the first to call Beat. Later, despite a growing rift between them, Sal and Dean travel again from Denver to New York; and later still, they go from Denver to New Mexico. What does it all mean? The search for “IT,” a cosmic truth, is never-ending. Fun fact: A hugely popular bestseller at the time; it’s considered one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.

- James Salter’s combat adventure The Hunters. Cleve Connell, Air Force fighter pilot, arrives in Korea with the goal of shooting down five MIGs — and thereby becoming an ace. Though he flies many combat missions (which are described thrillingly and gorgeously), he can’t rack up any kills… is he a coward? Unlucky? He and his fellow pilots — particularly Pell, a charming but ruthless lieutenant — compete viciously to achieve ace status; some of their kills put their comrades in danger; but Connell won’t do that. Whether 40,000 feet above the Yalu River, or in fighter pilot bars and hotels on the ground, he wages a battle for his own soul. Is winning everything… or is it all about how you play the game? Flying becomes an existentialist test of character. Fun fact: Considered one of the best flying novels of all time. Adapted in 1958 as a movie starring Robert Mitchum and Robert Wagner. Mark Kingwell tells us: “Robert Wagner is actually pretty good as a hipster, slang-slinging version of Lt. Pell.”

- Jim Thompson‘s crime adventure The Kill-Off. Luane Devore, a wealthy, neurotic invalid who spends her days spreading vicious rumors about everyone else in town — Manduwoc, a Jersey Shore resort that’s seen better days — is going to be murdered, this becomes clear right from the start. But who’s going to have done it? Her much younger husband, whom she tricked into marrying her and keeps on a short leash? Dr. Ashton, who’s sleeping with his black housekeeper? The town lawyer? The slutty big-band singer? The heroin-addicted teenage girl? Because each chapter of this thriller is written from the perspective of one of these characters, Thompson fans tend to love it or hate it — there’s no middle ground. Though it’s not one of the author’s very best efforts, I’m in the “love it” camp. Thompson’s knack for ventriloquizing the skewed, often dark perspectives and fantasies harbored by seemingly upright citizens is given a thorough workout, here. Fun fact: Adapted as an indie neo-noir film, in 1990, by Maggie Greenwald.

- John D. MacDonald’s psychological thriller The Executioners (aka Cape Fear). Released from prison after serving over a dozen years of a life sentence (for raping a minor, while he was in the Army), the brutal Max Cady heads like a bullet towards Sam Bowden, who’d been a key witness against him. Bowden is now a civilian, a happily married man with children living in Florida; he’s helpless to prevent the creepy ex-con from hanging around his lakeside village, making veiled threats. He’s a disaster waiting to happen. (“There are black things loose in the world. Cady is one of them. A patch of ice on a curve can be one of them. A germ can be one of them.”) After Bowden’s dog is poisoned, in a desperate attempt to protect his family — particularly his teenage daughter — he decides to take the law into his own hands. Fun fact: Adapted twice for the screen, in 1962 (with Robert Mitchum and Gregory Peck) and 1991 (with Robert DeNiro and Nick Nolte), as Cape Fear. MacDonald is best known for his 21 adventure novels — from The Deep Blue Good-by in 1964 to The Lonely Silver Rain in 1984 — starring Travis McGee.

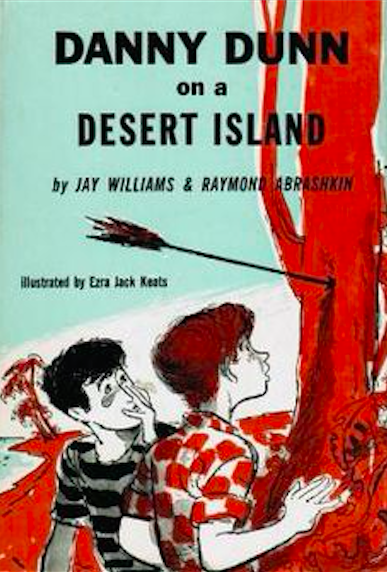

- Raymond Abrashkin and Jay Williams’s 1957 YA Robinsonade Danny Dunn on a Desert Island. The second of the fifteen Danny Dunn novels, in which adolescent scientist Danny, his friend Joe Pearson, Professor Bulfinch and Doctor Grimes crash land on an island near the Galapagos, is my favorite. Though far-fetched, it’s the least science-fictional of the series. Employing only whatever materials they happened to be carrying with them, the group demonstrates engineering know-how as they develop increasingly advanced technologies, then develop a plan to be rescued. (The book is dated in its depiction of island natives, though when Joe ends up in a big pot it’s not what you might expect.) Illustrated by the great Ezra Jack Keats. Fun fact: In Learning from the Left, Julia Mickenberg’s survey of radical political themes in Cold War-era children’s lit, she notes that the Danny Dunn adventures were intended by their authors — Abrashkin, who had been a journalist for the leftist paper PM; and Williams, who went on to write The Practical Princess and Other Liberating Fairy Tales — to introduce kids to scientific methods and concepts, and in doing so to suggest science’s liberating potential, i.e., versus the enchantment of the status quo.

Note that 1958 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Fifties. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Fifties; the titles on my 1958 and 1959 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Fifties adventure writing is all about: TBD.

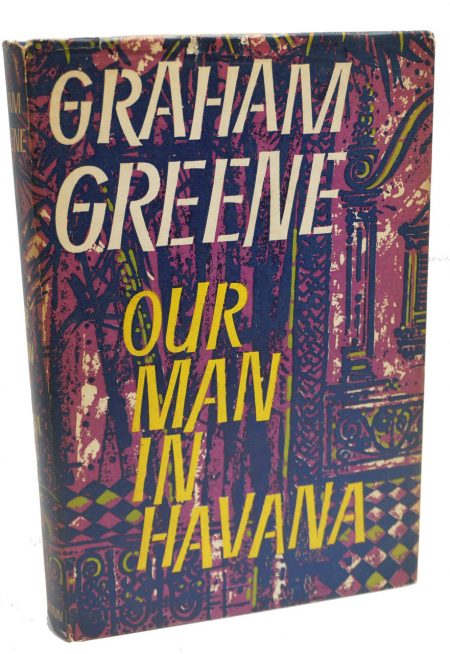

- Graham Greene’s sardonic espionage adventure Our Man In Havana. This black comedy set in (pre-Missile Crisis) Cuba, which Greene considered an “entertainment” rather than one of his serious novels, mocks the willingness of intelligence services to believe reports from local informants. Hard-pressed to satisfy his teenage daughter’s expensive tastes, Wormold, who owns a Havana vacuum-cleaner shop, begins selling invented information about agents and government installations (actually sketches of vacuum cleaner parts) to Britain’s MI6. Havana’s tawdry side is brought to life vividly, and the Batista regime is a chilling backdrop. When the real-life model for one of his imaginary agents is killed in apparent accident, Wormold must attempt to save the real people who share names with his fictional agents. Soon enough, an Soviet agent is assigned to assassinate Wormold himself… at which point, our man in Havana begins scheming to get his hands on an actual list of all of the spies in Havana — from Batista’s chief torturer. Fun facts: The book was adapted by Carol Reed as a 1959 movie of the same title starring Alec Guinness. PS: Greene was recruited by MI6 during World War II, and worked in counter-espionage in the Iberian Peninsula, where he had learned about greedy German agents in Portugal sending the Germans fictitious reports.

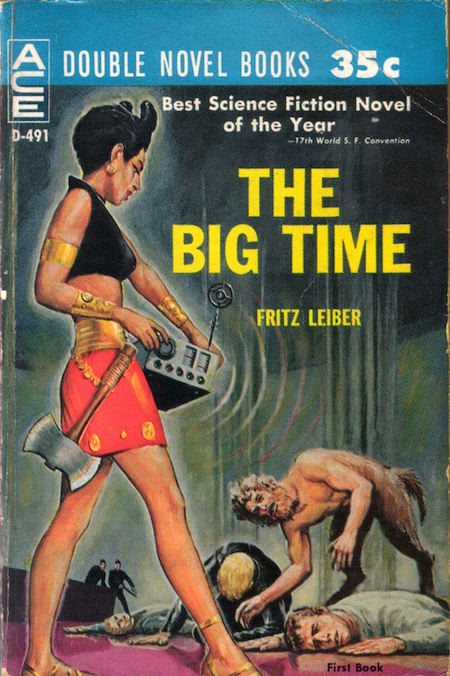

- Fritz Leiber’s sci-fi adventure The Big Time (serialized 1958; in book form, 1961). The Big Time is a far-out example of what I have elsewhere called the Crackerjack sub-genre of adventure — in which consummate professionals team up for a common purpose. (An immediate predecessor is, for example, The Guns of Navarone [1957].) Here, however, our crackerjacks are ten warriors from various eras of Earth and non-Earth history: e.g., Marcus (ancient Roman), Erich (Nazi), Kaby (female warrior from ancient Crete), Sevensee (satyr from the far future), not to mention Ilhilihis (octopoid extraterrestrial from the Moon’s distant past). Each of these characters was snatched out of his or her own time at the moment of his or her death, and shanghaied into the service of alien factions — known colloquially as the Spiders and the Snakes — who send them into battles across time and space, in an ongoing effort to alter the course of history. The so-called Change War, with its Stapledonian cosmic, era-spanning sweep, is merely a backdrop, however, to Leiber’s Sartrean chamber drama, which is set in a neutral Valhalla-like (it’s removed from the “little time” of history; hence the novella’s title) recuperation station for time warriors. Here, characters fall in and out of love, make speeches, and… deal with a time bomb set ticking by a saboteur! Fun fact: Originally serialized in Galaxy (March–Aril 1958). Winner of the 1958 Hugo Award — though it’s a very controversial Hugo winner. The terrific Hasbro boardgame Heroscape (2004–2010) seems directly influenced by this book.

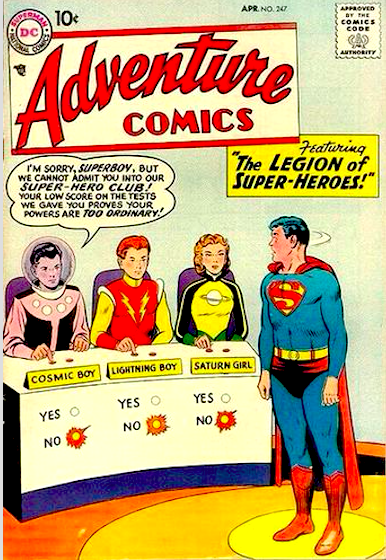

- DC Comics’ sci-fi adventure series The Legion of Super-Heroes (1958–on). When I was an adolescent, I couldn’t get enough of Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes (1977–1980, written by Paul Levitz/Gerry Conway, drawn by James Sherman); I’d also scour flea markets and comic shops for copies of the Legion’s previous series, Superboy starring the Legion of Super-Heroes (1973–1977), as well as Sixties-era copies of Adventure Comics featuring LSH stories. The Legion — the Silver Age of comic books’ first superhero team, created by writer Otto Binder and artist Al Plastino — first appeared in a 1958 issue of Adventure Comics, in which Lightning Lad, Saturn Girl (a telepath from Titan), and Cosmic Boy (who can generate magnetic fields) travel back in time from the 30th century in order to recruit Superboy. For the next two decades, the LSH would prove enduringly popular, thanks largely to fun characters like Chameleon Boy, Star Boy, Triplicate Girl, Bouncing Boy, Dream Girl, Ferro Lad, Matter-Eater Lad, Princess Projectra, Shadow Lass, Timber Wolf (who surely helped inspire Marvel’s Wolverine), Wildfire (a being of pure anti-energy), and — perhaps my favorite Legionnaire — the green-skinned, unstable genius Brainiac 5. I prefer the dissensual late-1970s version of the team; but the Mickey Mouse Club-like pre-Sixties LSH has its charms too. Fun facts: I can’t say that I’m crazy about post-1980 LSH reboots, threeboots, or retroboots. However, I did enjoy Mark Waid and Barry Kitson’s 2006–2008 run of Supergirl and the Legion of Super-Heroes, which was the temporary title of the Legion of Super-Heroes (Volume 5) from issues #16 to #36.

- Hergé’s Tintin adventure Tintin au Tibet (Tintin in Tibet, serialized 1958–1959; as an album, 1960). In his 20th outing, Tintin envisions his friend Chang (a Chinese boy who’d helped him out in The Blue Lotus), injured and calling for help from the wreckage of a crashed plane in the Himalayas — is it just a dream? No matter, Tintin, Captain Haddock, and Snowy immediately fly to Kathmandu, hire a sherpa and porters… and begin a hazardous trek towards the plane’s crash site. Mysterious tracks frighten off the porters, who believe that the abominable snowman who figures in the Himalaya people’s ancient legends and folklore is actually out there. While scaling a cliff face, Haddock slips and nearly kills Tintin; then, they lose their tent. Tintin sends Snowy to a nearby Buddhist monastery of Khor-Biyong for help… just before an avalanche hits. Is this the end of the Tintin saga? Fun facts: This was one of Hergé’s favorite Tintin stories; and the Dalai Lama awarded it the Light of Truth Award — because, he believed, Tintin in Tibet helps promote democracy and human rights for the Tibetan people.

- Robert Heinlein’s sci-fi adventure Have Spacesuit — Will Travel (1958). Having entered an advertising jingle writing contest on a lark, high-schooler Kip Russell wins a functional, but obsolete spacesuit. Although there’s no chance he’ll ever go to space, or even to one of Earth’s Moon colonies, Kip determinedly repairs and refurbishes the suit… and takes it out for a stroll. At which point, a UFO materializes. A young human girl, “Peewee,” who is the daughter of an eminent scientist and a genius herself, and an alien creature, which Peewee calls “the Mother Thing,” are on the run from another alien species. All three are captured by the horrific baddies (Kip dubs their leader “Wormface”) and taken to the aliens’ secret base on the Moon. From there, they travel to Pluto, and then Vega 5, the Mother Thing’s home planet; at every step of the way, Kip does his best to rescue his new friends. As if all this weren’t epic enough, in the end Kip and Peewee must intervene with an intergalactic tribunal on behalf of their planet! Fun fact: During World War II, Heinlein was a civilian aeronautics engineer working at a laboratory where pressure suits were being developed for use at high altitudes. Have Spacesuit — Will Travel is the last of his “juveniles” — sci-fi books for young readers. Serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

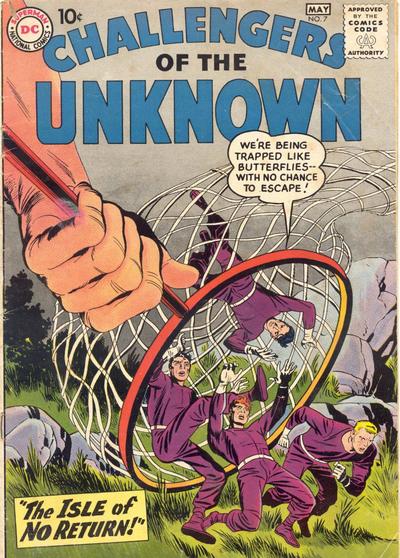

- Jack Kirby‘s pre-Silver Age sci-fi adventures (c. 1958–1961). Shortly before he and Stan Lee began their extraordinary run at Marvel Comics, capitalizing on a revived interest in superhero storytelling and revolutionizing the industry with The Fantastic Four (1961) and other titles, Jack Kirby spent three years freelancing for DC and Atlas — during which time he drew hundreds of pages of sci-fi comics. With writers Dick and Dave Wood, he co-created the Challengers of the Unknown, a quartet of jump-suited adventurers who investigated science fictional and apparent paranormal occurrences; the team — pilot Kyle “Ace” Morgan, daredevil Matthew “Red” Ryan, strong and slow-witted Leslie “Rocky” Davis, and scientist Walter Mark “Prof” Haley — is a precursor to The Fantastic Four. In the pages of DC’s Adventure Comics and World’s Finest Comics, Kirby recast DC’s Green Arrow as a science-fiction hero, complete with an Arrowcar and Arrowplane. Perhaps most importantly, during this period Kirby drew dozens of sci-fi and sci-fantasy stories (such as “I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers”) for Amazing Adventures, Strange Tales, Strange Worlds, Tales to Astonish, Tales of Suspense, World of Fantasy, and other anthologies such as DC’s House of Secrets, House of Mystery, and My Greatest Adventure. His monster stories, in particular — for example, Groot, the Thing from Planet X; Grottu, King of the Insects; Fin Fang Foom — are extremely fun.

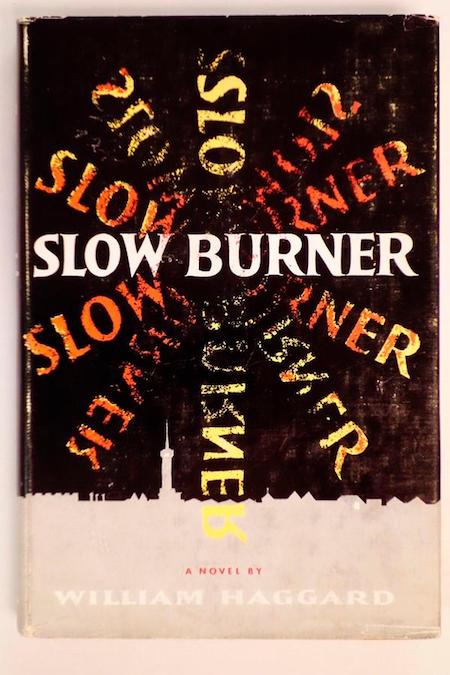

- William Haggard’s Colonel Charles Russell espionage adventure Slow Burner. In his debut outing, we meet Colonel Charles Russell — chief of the Special Executive, a (fictional) British counterintelligence service; the man who gives orders to field agents, that is to say; he is not himself an agent. Although there is some bang-bang action, here, Russell is primarily concerned with political maneuvering: Personal antagonisms within Britain’s intelligence community eventually lead to murder. At the same time, there’s a slow-burning plot-line about a British scientist selling top-secret military tech. Here we meet for the first time not only Russell but his assistant, Major Mortimer; Sir Jeremy Bates, Permanent Secretary at the Ministry; and Russell’s friend, the eminent scientist Dr. William Nichol, who directs a project developing a secretive nuclear fission process known as Slow Burner. Why are epsilon rays — the signature emission of the Slow Burner process — emanating from a suburban home outside London? Mrs. Tarbat, who lives in the house in question, has three lovers — is one of them a traitor? Charlie Percival-Smith, a disavowable third party, is brought in to investigate…. And there’s a frantic attempt, near the end, to prevent a nuclear accident near Oxford! Fun facts: Colonel Russell would go on to feature in a further 24 novels. “Haggard lacked [Ian] Fleming’s snooty dilettantism,” Christopher Fowler has written, “and was better at creating subtle layers of political intrigue.”

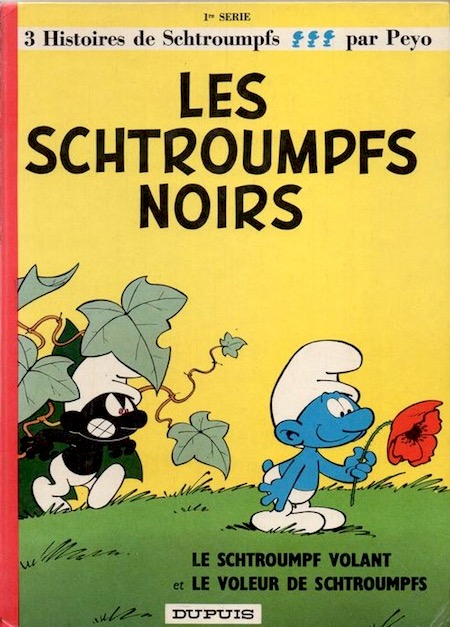

- Peyo’s fantasy adventure comic Les Schtroumpfs (The Smurfs, serialized 1958–1992). Forget the silly, often insipid 1980s Hanna-Barbera cartoon show, the unwatchable live-action/computer-animated movies from the 2010s, and the star-studded 2017 movie Smurfs: The Lost Village; forget the videogames, the songs, the toys and the theme parks. The Smurf comics from the ’60s and ’70s, created by the Belgian cartoonist Peyo, are actually pretty great. Hefty Surf, the tattooed strongman; Grouchy Smurf, the misanthrope; Clumsy Smurf, the dimwit; Jokey Smurf, the prankster; Vanity Smurf, the narcissist; Gargamel, the human sorceror who needs to catch a Smurf in order to create a philosopher’s stone; Papa Smurf, the tribe’s wise leader; and Smurfette, created by Gargamel to sow discord among the Smurfs… it’s an entertaining cast of characters, a young kids’ version of the Gaulish village created by France’s René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. (My only complaint is about Brainy Smurf, who’s just a jerk with glasses.) The Smurfs’ adventures — including a zombie apocalypse (Les Schtroumpfs noirs, serialized 1959), the rise of a proto-Trumpian populist would-be strongman (Le Schtroumpfissime, serialized 1964), the menace of a monstrous Howlibird, and a faked Moon landing — hold up well. Just be careful to avoid the many post-Peyo Smurfs comics. Fun facts: Peyo introduced the Smurfs in Spirou magazine, to which he contributed the series Johan and Peewit (1947–1977). The Smurfs got their own story in 1958, and were an immediate hit with readers.

- Brian Aldiss’s sci-fi adventure Non-Stop (also published as Starship). Upon the death of his wife, Roy Complain, member of a primitive tribe of hunter-gatherers who live in a territory surrounded by jungle-like “ponics” (plant growth) known only as “Quarters,” joins another tribe’s expedition into the heart of darkness… in order to discover more about the world in which they live. This is an apophenic adventure — the protagonists of which seek meaning. Why is their world made of plastic and steel? What lies beyond the jungle? What’s the deal with the intelligent rats? The expedition’s leader, a priest named Marapper, has found ancient documents which seem to suggest that “Quarters,” and other territories, are… a gargantuan spaceship, an interstellar ark, headed from and to unknown destinations, on which two dozen generations have already lived. Marker’s plan is to find the ship’s control room, and to divert the ship to the nearest habitable planet. What lies ahead — in the ship’s control center? Fun fact: This was Brian Aldiss’s first novel — and it reflects his view that entropy will always derail grand human projects.

- Muriel Spark‘s apophenic Robinsonade Robinson. When a plane en route to the Azores crashes on a tropical island, a hermit who calls himself “Robinson” grudgingly cares for its three survivors. Except for his naive young ward, the Friday- (or Caliban-)like Miguel, and a cat, Robinson is the sole inhabitant of the remote atoll; in fact, he owns it. The first half of the novel explores the characters of the castaways: January Marlow, an opinionated journalist whose journal we’re reading; Wells, publisher of an occult magazine and purveyor of lucky charms; and Jimmie Waterford, who turns out to have been looking for Robinson. The island is a perplexing dreamscape, full of strange sounds and sights; its inhabitants misunderstand each other; items are stolen; and January and Robinson argue about Catholicism; she is a recent convert, he has left the church. Then, Robinson disappears — leaving behind blood-stained clothes. Has he been murdered? If so, which of the remaining four characters might have wanted him dead? There’s a search; mounting tension; January speculates about who might have done it, and why; and, near the end, there’s a headlong flight from danger. The reader is left to ask: Whose story is this? Fun facts: Spark’s second novel is a sardonic inversion of, and meta-commentary on castaway tales such as The Tempest, The Island of Doctor Moreau, Lord of the Flies, and of course, Robinson Crusoe.

- Eric Ambler’s Robinsonade/crime adventure Passage of Arms. At the tail end of the so-called Malayan Emergency — a guerrilla war fought by the Malayan National Liberation Army and the military arm of the Malayan Communist Party — a Tamil plantation clerk discovers a cache of arms abandoned by Communist insurgents in the Malayan jungle. Looking to raise money (in order to start his own local bus service), he collaborates with Chinese brothers — located in Malaya, The Philippines and Singapore — in transferring the arms to Indonesia. When the shipment is held up, en route, a representative of the family offers to pay Greg Nilsen, who runs a small manufacturing company in Baltimore, a handsome fee if he’ll travel to Singapore to act as the shipment’s bonded recipient. Nilsen and his wife, Dorothy, were on a South China Sea cruise at the time, but he was looking for more excitement. He finds it! Although this is a slow burner, Nilsen will learn more than he ever wanted to know about the shipment of illegal weapons across borders as he encounters Communist agitators, anti-Communist rebels, prison and probable torture on Sumatra. (He’s not the quiet American — just a thoughtless, thrill-seeking one — though Graham Greene’s novel is referenced, humorously.) I’ve classified it as a crime adventure, but Passage of Arms has also been described as a travelogue that turns into a horror story; and there’s enough here about the Tamil clerk’s aspirations to qualify it as an entrepreneurial Robinsonade à la Nevil Shute. The real action takes place in the final third of the book; there is a battle scene which no doubt owes its authenticity to Ambler’s wartime service. Fun facts: Ambler, who’d introduced a new realism to the espionage thriller genre with his 1936–1940 output before enlisting in the British army during WWII, would later often turn to stories involving corporate-political shenanigans in exotic Third World settings. This is the first example the second, post-war phase of Ambler’s oeuvre. PS: The book’s title is a pun on the 15th-century “passage of arms,” a knight’s challenge to traveling knights.

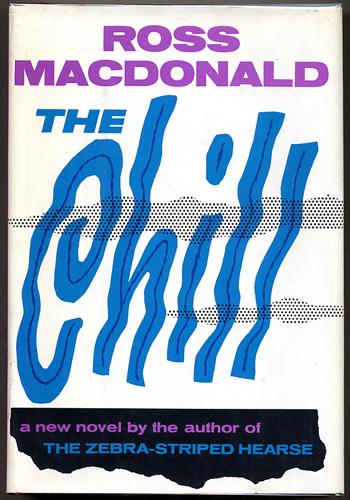

- Ross Macdonald‘s Lew Archer crime adventure, The Galton Case. Mrs. Galton, a wealthy woman near the end of her life, hires suburban Los Angeles private eye Lew Archer — this is his eight outing — to track down her prodigal son, Anthony, from whom she has been estranged for 20 years. It seems that a chunk of the Galton family fortune went missing, along with Anthony — so this is a treasure hunt, as well as a whodunit and a psychological thriller. The story takes Archer to San Francisco, to a small town on the California coast, and to Detroit; his quest gets tangled up with the mysterious death of Peter Culligan, houseman to Mrs. Galton’s lawyer, Mr. Sable. As with most Archer stories, the crime in the present is linked to a crime in the past; Oedipal dynamics, childhood trauma, and tortured psychologies are Macdonald’s bread and butter. The book’s prose style is pure pleasure, and its plot structure is carefully considered — nothing is as it seems. Fun facts: Ross Macdonald (Kenneth Millar) has been called the heir to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler as the master of American hardboiled mysteries. In a 1973 interview, he would recount that “I was forty-two when I wrote The Galton Case. It had taken me a dozen years and as many books to learn how to tell highly personal stories in terms of the convention I had chosen.”

- Shirley Jackson’s psychological/occult thriller The Haunting of Hill House. Dr. Montague, an investigator of the supernatural, rents Hill House — an isolated, supposedly haunted manion, in an unspecified location — for the summer. He brings along Luke, a handsome and wealthy young man who will one day inherit Hill House, as well as two women who have experienced the paranormal: Theodora, a flamboyant, bohemian artist; and Eleanor, a shy young woman who has been living as a semi-recluse while caring for her mother. Eerie events transpire: there are unseen noises, ghostly apparitions, strange writing on the wall. Eleanor, in particular, experiences phenomena to which the others are oblivious — but is she imagining some, or all of it? Or might Eleanor possess a subconscious telekinetic ability that is causing some or all of these manifestations? Jackson’s prose style is extraordinary: objective to an alienating degree, early on, as though to illuminate the inherent oddness of a scientist’s viewpoint; later, increasingly fraught. The house itself isn’t described, in physical terms; but it’s an important character in the book — a lonely, possibly insane presence that almost seems to have been waiting for Eleanor to arrive. A foolish, yet insightful character, Mrs. Montague, shows up at a certain point — for comic relief? Or is she a Shakesperean fool? When it finally becomes clear that Eleanor must leave Hill House, the question is… can she do so? In time? Fun facts: Jackson is probably best known for her short story, “The Lottery” (1948). The Haunting of Hill House is considered one of the greatest haunted house tales ever written; it was an important influence on The Shining. Robert Wise’s 1963 film adaptation, The Haunting, stars Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, and Russ Tamblyn. There’s also a 2018 TV miniseries from Netflix.

- Daniel Keyes’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure Flowers for Algernon. Charlie Gordon has an IQ of 68. The 32-year-old does menial work for a living, and attends reading and writing classes at the Beekman College Center for Retarded Adults. Two Beekman researchers have succeeded in dramatically increasing the intelligence of a lab mouse (Algernon), through experimental brain surgery; and Charlie is selected as their first human subject. The novel is epistolary — we’re reading Charlie’s own progress reports. When his IQ dramatically increases to genius level, Charlie realizes how poorly the people in his life have treated him… except for Alice, his beautiful reading teacher, on whom he has an unrequited crush. Charlie’s own research into the intelligence-enhancing procedure he’s undergone suggests that it is flawed… and when Algernon reverts to his previous intelligence, then dies, he’s convinced that he is doomed. How will he choose to live, now? Fun fact: First published, as a story, in the April 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction; it won the 1960 Hugo. The 1966 novel version was joint winner, with Babel-17, of the Nebula. Cliff Robertson won the Oscar for his portrayal of Charlie in the 1968 film Charly.

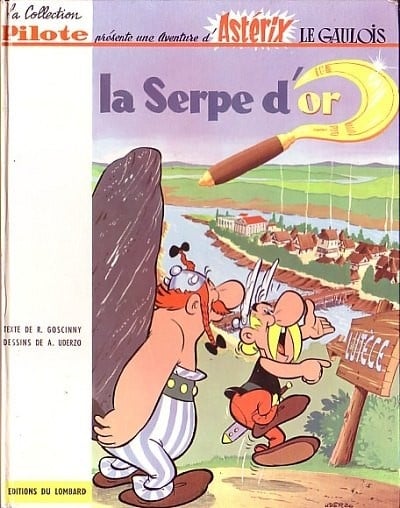

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Asterix comic Astérix le Gaulois (Asterix the Gaul, serialized 1959; as an album, 1962). In 1958 Goscinny, who in the late 1940s had shared a New York studio with future MAD contributors Will Elder, Jack Davis and Harvey Kurtzman, and Uderzo began serializing Oumpah-pah — a cartoon about an American Indian whose village was bravely holding out against the palefaces — in the Franco-Belgian comics magazine Tintin. The following year, the two men became editor and artistic director of Pilote magazine, which was intended to appeal to adults as much as to children. Here, they introduced a cartoon about Astérix, a Gaul whose village was bravely holding out against the Roman occupiers. (Vercingetorix, leader of the Gauls in a notable rebellion against Julius Caesar in the late 50s BC, is revered in France as the original French resistance fighter.) Centurion Crismus Bonus, commander of a Roman garrison at the fortified camp of Compendium, sends a spy disguised as a Gaul into Astérix’s village — to discover the secret of their indomitability. When the spy reports that the Gaul’s druid, Getafix (Panoramix in the original French version), brews a potion conferring magical strength on its users, the druid is kidnapped; Astérix sneaks into the Roman camp, and he and Getafix play pranks on the Romans… until Caesar himself arrives! The combination of sophisticated word-play, historical and contemporary social and political commentary, slapstick comedy and violent punch-ups is irrestisible; the series was an immediate success. In this story, we also meet the characters Obelix, Vitalstatistix, Cacofonix (Assurancetourix), and others for the first time — it’s fun to observe how they’ve evolved. Fun facts: In France, Astérix is the most popular comic of all time — more so than Tintin, even. (When Goscinny died in 1977, it was, in the words of one French obituary, “as if the Eiffel Tower had fallen down.”) The English translations of the Astérix books, by Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge, are impressive — their wordplay is just as clever.

- Kurt Vonnegut’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure The Sirens of Titan. What if? A space explorer — Rumford — were to stumble into a chrono-synclastic infundibulum (a spiralling point in space/time “where all the different kinds of truths fit together”), and as a result, became omniscient about past and future happenings throughout the galaxy? If the richest man in the America of that distant future — Malachi Constant — were to cross paths with Rumford on Titan, in the midst of humankind’s preparations for an interplanetary war, what would Rumford tell him about free will, God, and the purpose of human history? (Could humankind’s progress in fact be pointless and pathetic?) If Rumford (and his dog, Kazak) were to materialize on Earth and other planets, at various points in history, would he for some reason instigate a Martian invasion? Would he start a religious movement — the “Church of God the Utterly Indifferent” — in order to unite humankind after the invasion? (Hello, Ozymandias from Watchmen.) And why? A (mostly) bleak and ironic mini-epic, post-Olaf Stapledon and pre-Douglas Adams. Fun fact: Vonnegut sold the Sirens of Titan film rights to Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead. The movie adaptation was never made.

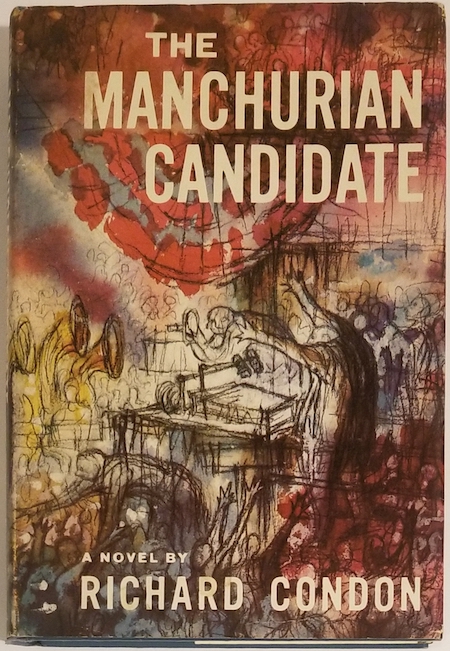

- Richard Condon’s political thriller The Manchurian Candidate. Several years after Bennett Marco, Raymond Shaw, and the rest of their Korean War infantry platoon were captured by a Soviet commando unit and held captive in Manchuria, Marco suffers from a recurring nightmare. In it, sweet little old ladies, who are somehow also Chinese and Soviet officials, command Shaw to murder two of his comrades. But Shaw is a hero; and those two men died in combat… right? Marco — now an Army Intelligence officer — looks up Shaw, whose stepfather is a prominent McCarthy-esque politican, Senator Johnny Iselin — and the two men become friendly. Marco gets involved with a supportive woman, Rose, while Raymond falls for the girl next door. Jocelyn is the daughter of Senator Jordan, a political foe of Iselin’s; Raymond’s ambitious, domineering mother Eleanor disapproves… but Raymond continues to see Jocelyn. Meanwhile, Marco uncovers an audacious plot — backed by the Communist powers — to install an American president of their choosing, who will become their stooge! Raymond is an unwitting participant in this nefarious scheme. Can Marco get to the bottom of the plot before it’s too late for Raymond… and America? Condon’s prose style is strong medicine; there are verbal pyrotechnics to complement the mind-bending plot. Fun facts: Several passages of the novel, it has been suggested, were plagiarized from Robert Graves’s 1934 novel I, Claudius. The Manchurian Candidate was adapted by John Frankenheimer as an excellent 1962 movie starring Frank Sinatra, Laurence Harvey and Janet Leigh, with Angela Lansbury in a chilling role. There is also a 2004 remake starring Denzel Washington.