BESTIARY (2)

By:

March 5, 2021

One in a series of posts — curated by Matthew Battles — the ultimate goal of which is a high-lowbrow bestiary.

The owl is a mostly solitary, nocturnal bird of prey typified by its upright posture and enormous, forward-facing eyes. Its iconic (I use the term, here, in its biosemiotic sense) attributes tend to elicit or provoke in humankind the same ambiguous response that can be triggered by a close encounter with a learned, sagacious, perspicacious human being.

That is to say: Although most of us instinctively feel respect, even veneration for this bird, a surprising number of us instead feel harshly judged by it… which sparks in us a preconscious, irrational desire to take the pompous owl down a peg.

We might call this state of affairs: Overawing Owl Syndrome.

As evidence of this unfortunate syndrome, I submit the following non-exhaustive list of pop-culture depictions (some old, some contemporary) of the order Strigiformes which I encountered during my formative years — i.e., the Seventies (1974–1983).

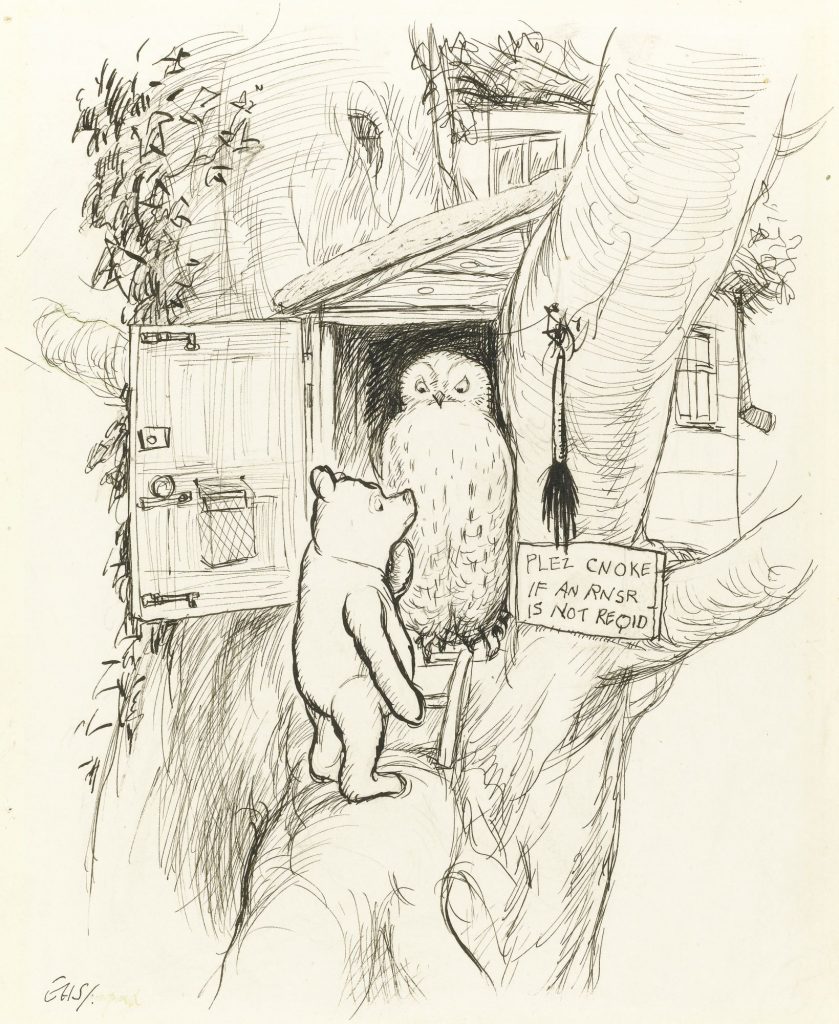

- Owl, the live owl who dwells among the toy animal characters in A.A. Milne’s 1926 story collection Winnie-the-Pooh and its sequels and subsequent cartoon adaptations. The only character who isn’t stuffed, Owl is the stuffiest one; full of himself, he presents himself as a mentor and teacher… the joke being that he’s illiterate, scatterbrained, and prone to using words incorrectly. (His home is decorated with a sign that says “WOL”; the birthday card for Eeyore that he writes on Pooh’s behalf reads, “HIPY PAPY BTHUTHDTH THUTHDA BTHUTHDY”; when Rabbit comes to Owl to discuss a notice that Christopher Robin has left, Owl must trick Rabbit into reading the notice aloud; and so forth.) Like other pop-culture owls, Owls often wears glasses… as a stratagem designed to make himself look wiser than he is.

- Judge Owl. Owls wearing glasses and/or mortarboards are a whole thing. In the 1935 Silly Symphony, “Who Killed Cock Robin,” for example, the stern and disciplinary owl judge sports both accoutrements. Compare with the mortarboard-wearing Owl teacher, who in the last scene is electrocuted by a student, in Ub Iwerks’s Snow Time (1938), for example; and this 1940s postcard of an owl teaching Pixy School. Clearly, this was a popular meme at the time.

- Professor Fritz Owl, father of “Owl Jolson” in the 1936 Merrie Melodies animated cartoon “I Love to Singa,” directed by Tex Avery. Professor Fritz, who speaks with a German accent, is a disciplinarian and mandarin voiced by Billy Bletcher, best known for voicing cartoon villains like Black Pete (Mickey Mouse films) and the Big Bad Wolf. His intolerance for jazz leads him to banish one of his owlets from their tree, for the crime of singing the Arlen and Harburg tune “I Love to Singa” (popularized by Al Jolson and Cab Calloway) at every opportunity. Everyone’s favorite Warner Bros. cartoon, “I Love to Singa” helped popularize in US culture the owl as a symbol of pompous Old World culture. PS: See this 1935 short in which a glasses-wearing owl student is portrayed as a snooty prig on whom his classmate plays a prank; compare with the impish owl student, who ends up wearing his vanquished teacher’s mortarboard and gown, in Teacher’s Pest (1950).

- The Owl Who Thought He Was God. I encountered this James Thurber fractured fable, which first appeared in The New Yorker in April 1939, in the 1940 collection Fables For Our Time, where it was retitled The Owl Who Was God. Long before Jerzy Kosiński’s Being There, Thurber warned about the dangers of placing too much faith in someone who merely appears to be wise… because they utter cryptic, gnomic statements. Excerpt: “He walked very slowly, which gave him an appearance of great dignity, and he peered about him with large, staring eyes, which gave him an air of tremendous importance. ‘He’s God!’ screamed a Plymouth rock hen. And the others took up the cry ‘He’s God!’ So they followed him wherever he went and when he bumped into things they began to bump into things, too.” Things do not end well for the animals, or the owl.

- Friend Owl. Voiced by Will Wright, frequently cast in westerns as a curmudgeonly and argumentative old man, Friend Owl is a curmudgeonly figure of fun in the 1942 animated Disney movie Bambi. The advice he offers to Bambi and his friends about the perils of becoming “twitterpated” (falling in love) is alarmist and rather cruel.

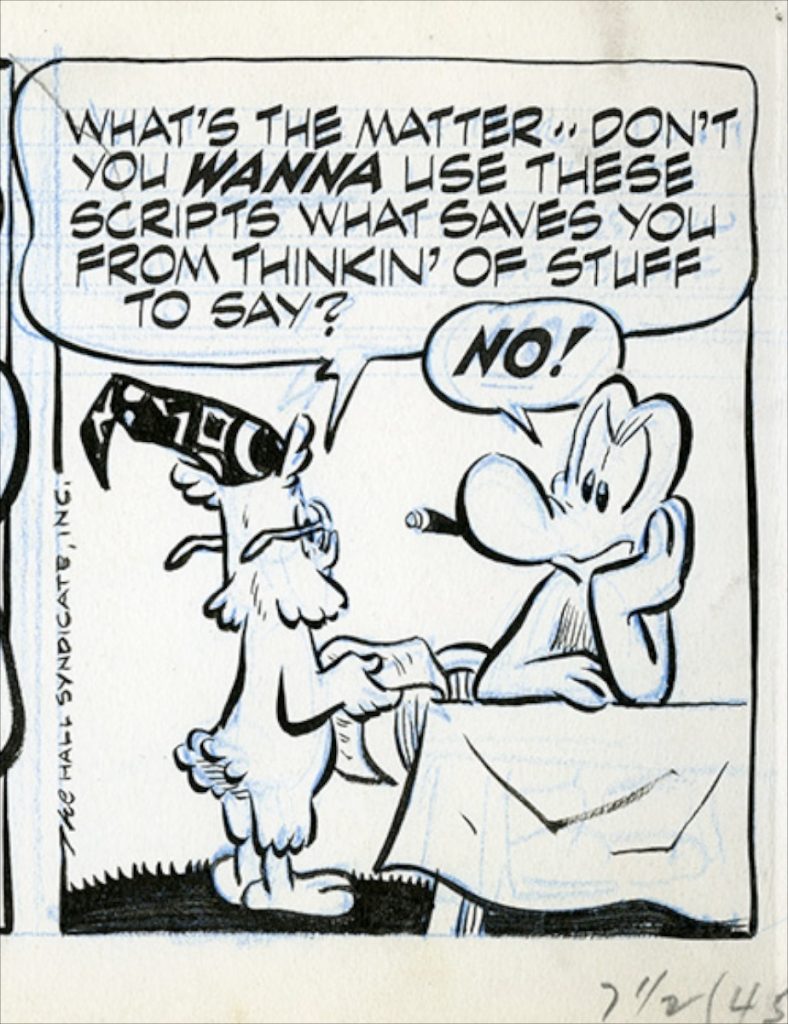

- Howland Owl, from Walt Kelly’s (1948–1975) newspaper strip Pogo. “Perfesser” Howland, like so many other pop-culture owls, is a self-appointed authority on… everything. Sporting horn-rimmed eyeglasses and, in his earliest appearances, a pointed wizard’s cap, he presents himself as a scientist, doctor, astronomer, and so forth; in fact, he is a dangerously inept buffoon who misuses large words, readily believes in obviously false theories and notions, and gets his friends into one scrape after another. One wonders whether the wizard’s cap — which fortuitously resembles a dunce’s cap — is a reference to Merlyn’s owl in T.H. White’s 1938 novel The Sword in the Stone.

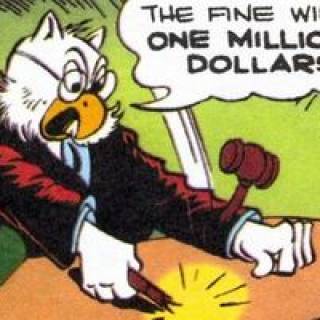

- Judge Owl. In the Donald Duck universe, Judge Owl is an authoritative, punitive magistrate in Donaldville. He first appeared in a 1936 illustration, “Judge Owl on the Bench,” in the pages of Mickey Mouse Magazine; was the character inspired by the 1935 cartoon short “Who Killed Cock Robin” (see above), one wonders? He became a recurring character as of an April 1949 Carl Barks story called “Rival Beachcombers.” In which Judge Owl fines Donald $5,000.00 for digging up the beach, in search of a maharajah’s lost ruby. He would go on to levy many harsh judgments against Donald, Uncle Scrooge, and others.

- Professor Owl, who first appeared in the 1953 Walt Disney animated shorts Melody and Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom, in which he instructs a class of birds about the fundamentals of music. (Designed by Ward Kimball, and voiced by Bill Thompson, who also played Mr. Smee in Peter Pan, among many other cartoons.) My elementary school must have aired these shorts for us half a dozen times; I remember them well. Professor Bird is not a blowhard or con man, in fact he is an engaging and talented educator, but he is (a) stern with recalcitrant pupils, and (b) somewhat clumsy and hapless. PS: In the 1980s, Disney rebooted the character as the host of their Sing Along Songs series.

- I’m too young to have encountered the 1955 poster, above, by the great Garth Williams. But I just wanted to include it here.

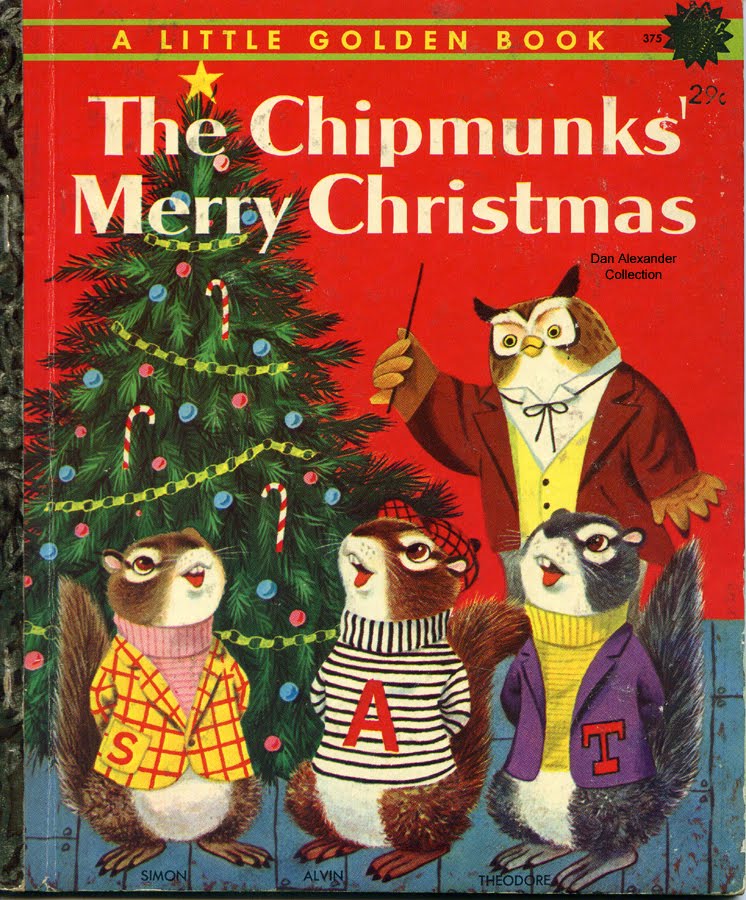

- Mr. Owl, in the owl music teacher in David Corwin and Richard Scarry’s The Chipmunks’ Merry Christmas, a 1959 Little Golden Book — one of the first Alvin and the Chipmunks books. Like several of his pop-culture predecessors, Mr. Owl is a strict taskmaster dressed in a rather old-fashioned suit, complete with waistcoat.

- Archimedes, in the 1963 animated movie adaptation of T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone. Merlyn’s familiar, in White’s book, is far from illiterate, in fact he’s highly educated… though he is crochety and easy to displease. He engages in Socratic dialogues, of a sort, with Merlyn… and generally seeks to prevent the wizard from acting the fool. (Per the discussion of Howland, above, Archimedes is closely associated with Merlyn’s magician’s hat: he sits atop of it, Merlin keeps dead mice inside it for him, and at one point he advises Merlin on the best way to command a daemon assistant to fetch it.) Voiced by Junius Matthews, who was the original voice of Rabbit in the Winnie the Pooh franchise, in the Disney movie — which is inferior in every possible respect to the book — Archimedes is a figure of fun, a highbrow type who although no buffoon is constantly wrong-footed by Merlyn and made to look foolish and inept. PS: Here’s a guide to owls in Disney movies.

- Ollie the Owl. In a December 1963 cartoon, “Ollie the Owl,” from Noveltoons — the Paramount Pictures’ Famous Studios anthology series that brought us animated versions of Casper the Friendly Ghost, Wendy the Good Little Witch, etc. — Ollie is a child prodigy who uses a detective kit to outsmart and arrest a bank robber. In a 1964 appearance, in a short called “Whiz Quiz Kid,” Ollie goes on a children’s quiz show and answers all the questions correctly, to the dismay of the corrupt TV studio execs.

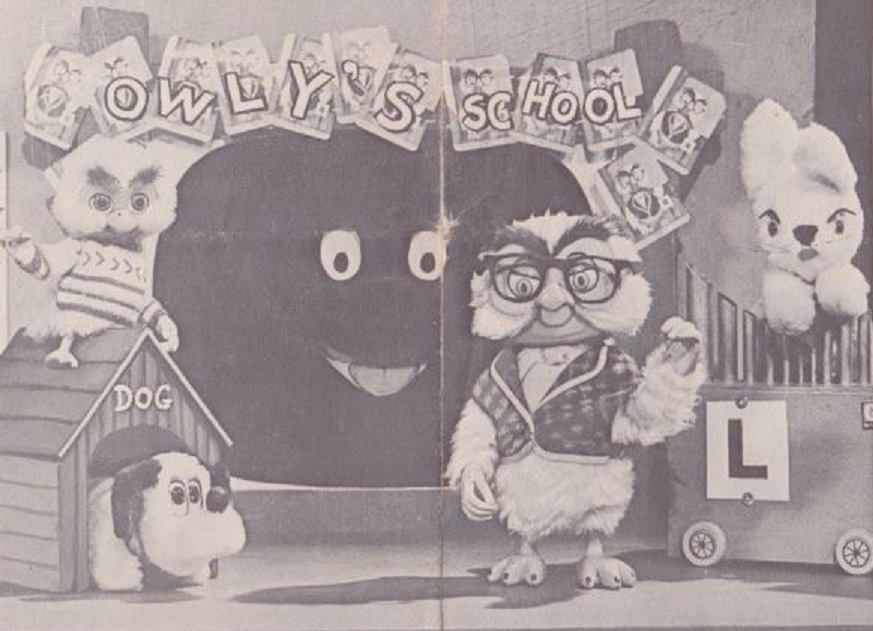

- Owly, star of the 1965–1968 morning children’s show Owly’s School deserves a mention — though it was an Australian marionette and puppet educational show that I’ve never seen. Featuring Mr. Owl, “Blackboard,” Neddy Nibbles (a rabbit that played the organ), an invisible pianist, and a live cat known as Friend Cat Pussy Cat. The theme song was “We’re going to Owly’s School, We’re going to Owly’s School, oh yes oh yes oh yes oh yes we’re going to Owly’s School.” One wonders whether this was a direct influence on Pee-wee’s Playhouse (1986–1990)?

- X the Owl, a puppet character in the (1968–2001) children’s TV show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. X is a blue-feathered owl who lives in the oak tree at the center of Make-Believe. Because this show is so essentially good-hearted, X — voiced by Rogers — is not a figure of fun. A passionate learner, he immerses himself in lessons delivered by the Owl Correspondence School; however, he is more of a passionate amateur than a truly wise figure. Slightly ADD, perhaps, X is forever studying a new topic… and one never gets the impression that he has mastered any of them. He’s also easily frustrated when things don’t go his way, and has a tendency to be chronically indecisive.

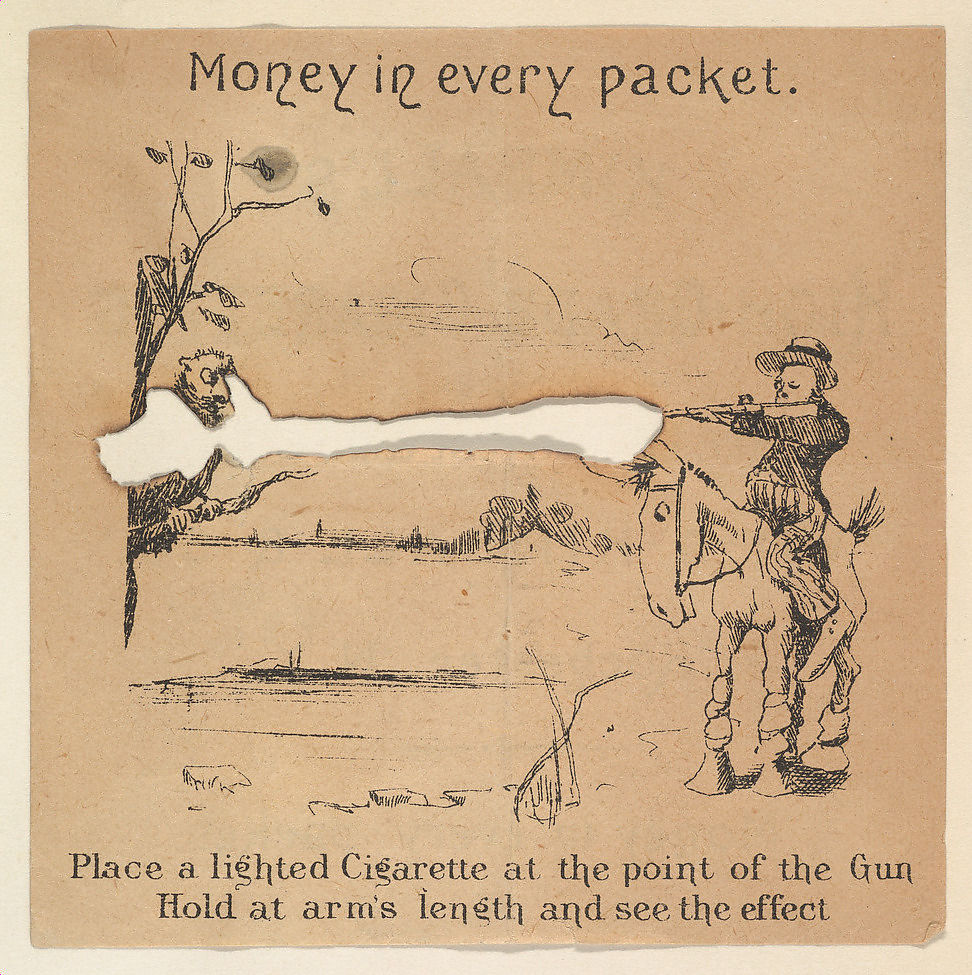

- Mr. Know It Owl, who appeared in a long-running commercial that first aired in either 1969 or 1970. “How many licks does it take to get to the Tootsie Roll center of a Tootsie Pop?” demands a child of several animals (a cow, a fox, a turtle) ventriloquized by well-known voiceover actors of the day. Instructed to direct his enquiry to “the wisest of us all,” the child finds his Tootsie Pop appropriated and eaten by Mr. Owl, whose glasses and mortarboard make him appear a harmless pedant… when in fact he is a trickster, a con artist. “If there’s one thing I can’t stand,” the dejected child says at the end of this fractured fable, “it’s a smart aleck.” PS: Directed by Jimmy T. Murakami, known for his far-out work on Breath (1967), Heavy Metal (1981) and When the Wind Blows (1986).

- Dr. Blinky, from the 1969 Sid and Marty Krofft live-sized puppet TV show H.R. Pufnstuf. Voiced by Walker Edmiston (doing an Ed Wynn and/or Frank Morgan impersonation), Dr. Blinky is an owl doctor and scientist — and head of the Anti-Smog, Pollution, and Witch Committee. In his laboratory — which must have been an influence on Gary Panter’s design for Pee-wee’s Playhouse — every single object is animated. Dr. Blinky seems to be a genius, but he’s also something of a crackpot; his experiments have a tendency to explode. He’s something of a Wizard of Oz figure — he sends others off to battle the witch, he never seems to quite have a grasp on the situation….

- Charlie Owl, a costumed full-bodied puppet character on the children’s TV show The New Zoo Revue (1972–1977). Charlie (voice by Bob Holt) is a scientist and inventor whose tree is fitted out with an elevator. He is indeed brilliant, but he is also an over-serious know-it-all… a precursor of sorts to Sheldon Cooper on The Big Bang Theory. For example, in an effort to outdo the Nobel Prize, Charlie (who wears a collar and tie, and a scholar’s mortarboard) awards a “One-Bell Prize.”

- Doktor Bubó. I didn’t see this show as a child, but worth mentioning here. Kérem a következőt! (literally: “Next one, please!”) is a 1973–1974 Hungarian animated series produced by Pannonia Film Studio. The show stars an owl psychologist, Doktor Bubó, who attempts to stop a trouble-making animal by psychological methods… only to fail every single time and cause even bigger trouble. PS: Note that the American horned owls and the Old World eagle-owls make up the genus Bubo; Bubo is Latin for “Eurasian eagle-owl.”

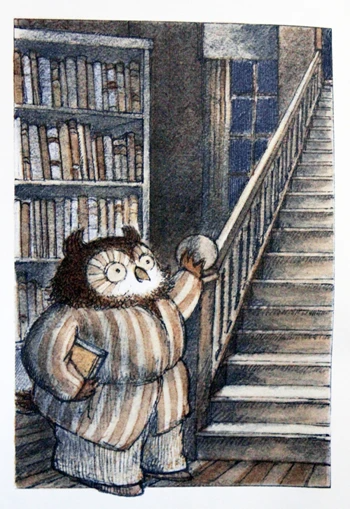

- Owl, in Arnold Lobel’s 1975 children’s book Owl at Home. A lovely I Can Read book about a bookish, semi-reclusive owl who gets himself into various domestic jams and mishaps because of a certain innate cluelessness. PS: Compare with the bookish, apartment building-dwelling owl in Paula Scher and Stan Mack’s 1973 children’s book The Brownstone.

- Bubo, in 1981’s Clash of the Titans. Athena has Hephaestus fashion a clockwork duplicate of her own owl, and sends it to Perseus as a guide and helper. Although a figure of fun, to some extent, Bubo is also brave and ends up saving the day. The film features the final work of legendary stop-motion visual effects artist Ray Harryhausen.

Milne’s “Wol” is an early example of the owl as an avatar of the trope “Know-Nothing Know-It-All.” TV Tropes notes that “Owl is an example of a dead subtrope which was common back then; a Victorian school graduate with surface knowledge and a lot of arrogance.” An even earlier example can be found in L. Frank Baum’s The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913), in which the Foolish Owl is a public adviser who speaks in nonsense poetry, which her Wise Donkey colleague translates into good advice.

I expect to be inundated with suggestions about David Bowie’s owl avatar in Labyrinth (1986), etc., etc. Happy to receive this sort of thing, but note that I’m most interested in pre-1980 examples. No Harry Potter or Guardians of Ga’Hoole stuff, please.

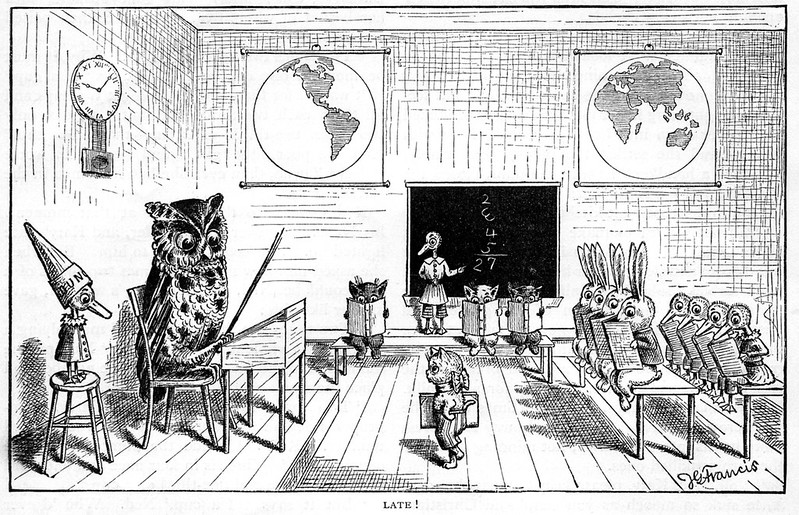

The owl-as-teacher meme that we find referenced in so many examples above dates back to 19th-century children’s books depicting an owl as a strict, non-ridiculous schoolteacher. The image above, for example, is from an 1879 issue of the children’s periodical St. Nicholas Magazine.

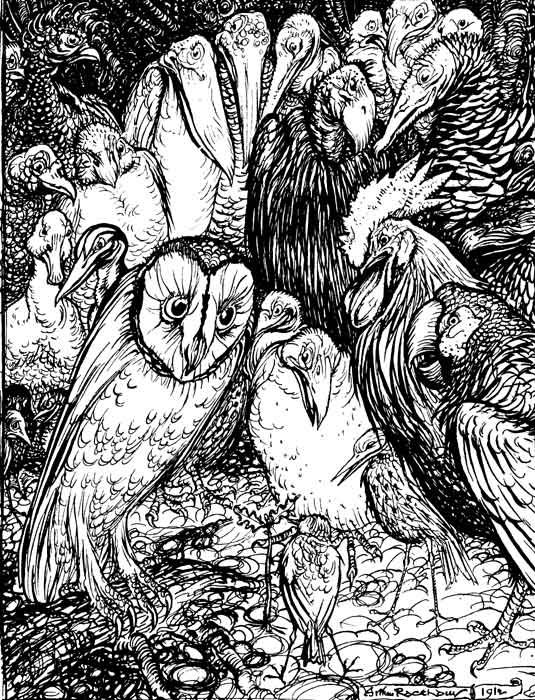

One assumes that this precursor meme is itself attributable to Aesop’s fable “The Owl and the Birds,” in which the silly birds ignore the owl’s wise counsel: Nato autem visco, cum iam facile ab hominibus caperentur, sero paenitentiam egere noctuamque de consilio sunt admiratae. Ad illam accedunt, at accedunt frustra, accepto malo. The image below, by Arthur Rackham, is from his 1912 edition of Aesop’s Fables. Here, the owl looks thoroughly fed up with the nincompoops who surround him.

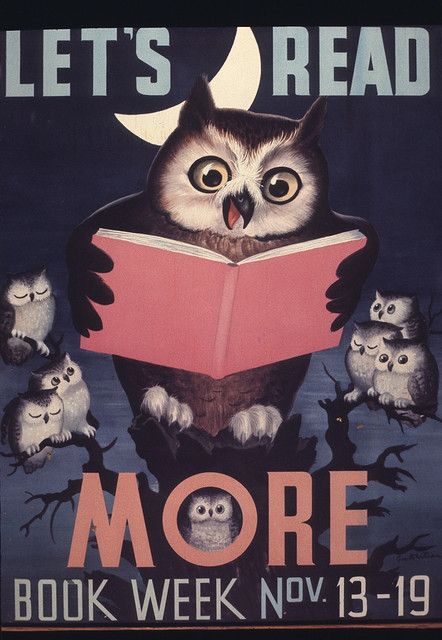

Other early examples of owls teaching and reading: a 1908 image of an owl who seems to be adjudicating among rabbits; a 1913 image of a literate owl reading a book; and a 1921 image in which a “wise owl” offers advice to other animals. This excellent image of a mortarboard-sporting owl teacher was produced as a postcard by Medici Society, which was founded in the UK in 1908; the precise date of the image is unclear.

Below: Try searching for vintage owl bookplates and bookmarks, or just search for “owls + books”; again, it’s a whole thing.

Why have humans — for millennia — been unable not to perceive owls as being wise? And why should an encounter with a wise figure inspire in (some of) us a desire to see that figure exposed as a fraud, humiliated?

As I’ve suggested above, the answer to the first question surely has something to do with the owl’s iconic attributes. The field of biosemiotics teaches us that icons are meaning-bearing sign vehicles whose function it is to elicit or provoke, at a preconscious level, a particular space-time interaction. (Ants don’t choose to “milk” aphids for honeydew, for example; they are impelled to do so by the iconicity of the aphid’s rear end… which resembles an ant’s head.) The owl’s most noticeable iconic attribute is, of course, its eyes.

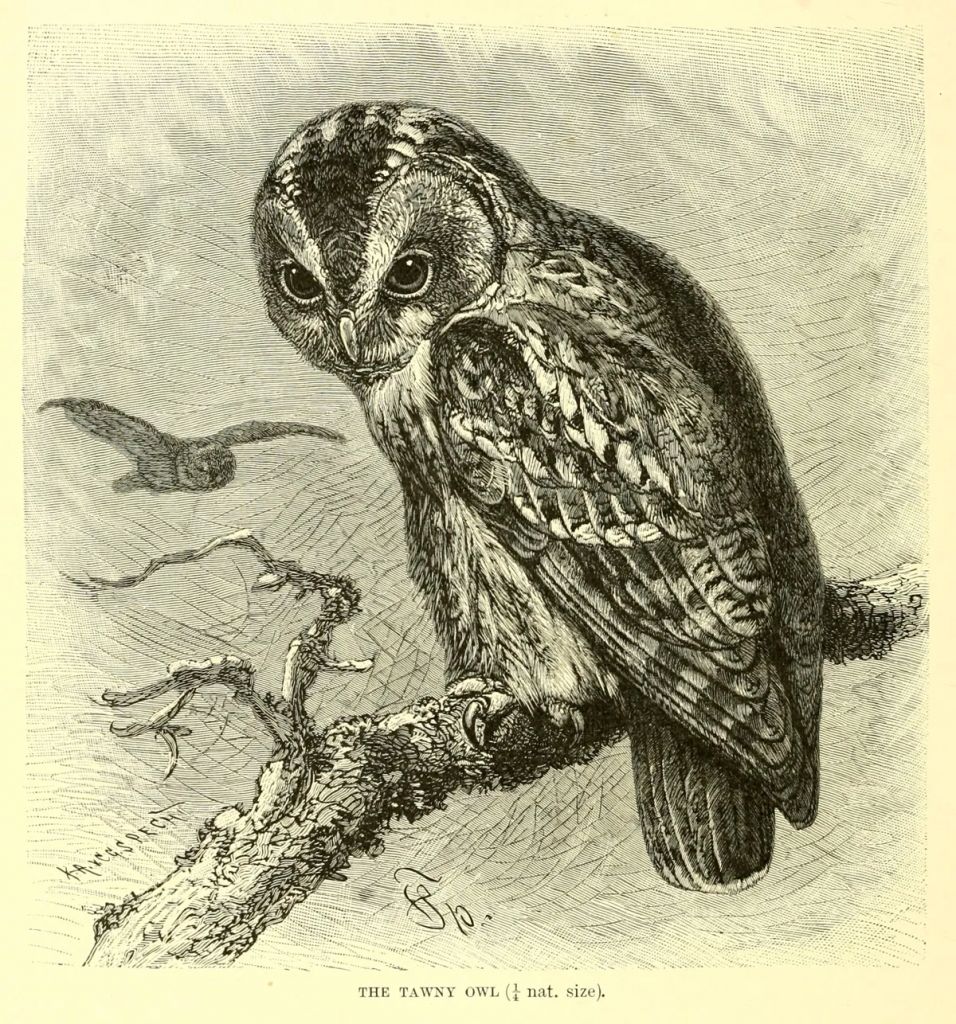

Most birds have eyes on either side of their head; not so the owl, whose forward-facing eyes remind us of our own. But whereas eyes account for a mere .0003% of a human’s body weight, an owl’s huge eyes can account for 3% of its weight. The owl’s eyes are shaped like tubes, not orbs, and are held in place by sclerotic rings. As a result, their eyes cannot move or roll; instead, owls have evolved the ability to rotate their heads up to 270°. The owl seems to see all, and — thanks to the nocturnal creature’s habit of sitting quite still when we encounter it by day — to know all. It seems sagacious, judicious, discerning, perspicacious.

Though not every ancient culture depicted owls as wise, Western culture’s progenitors — the Ancient Greeks and Romans — certainly did. They associated the owl with Athena (in syncretic Roman mythology: Minerva), the goddess of wisdom herself. Why? Perhaps because the concept of Athena evolved from an early goddess associated with birds; or else because owls were common in Athens, which took its name from the goddess. Surely, however, the owl’s iconic attributes played a major role in prompting the association of the creature with Athena and wisdom.

As the symbol of Athens, the birthplace of Western civilization, the owl was surely an important symbol during the Age of Enlightenment, a now-defunct intellectual and philosophical fad that proclaimed the sovereignty of reason, the evidence of the senses as the primary sources of knowledge, and now all-but-forgotten ideals such as liberty, progress, toleration, fraternity, and the separation of church and state.

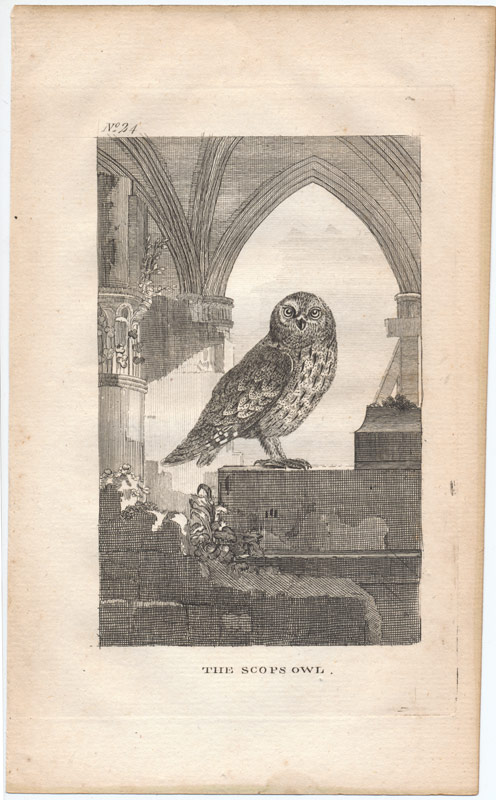

The French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788), for example, bequeathed to us the magnificent copperplate engraving below, in which a Scops owl seems to scornfully preside over the decline of superstition.

Although my effort to demonstrate that the owl was the totem animal of Jean-Jacques Rousseau failed (in fact, he compares the appearance of two of his least favorite people — in The Confessions — to owls), behold the chocolate “Owl Lollie” produced by the suggestively named Rousseau Chocolatier.

Suffice it to say, for the moment, that from Ancient Greece through the early nineteenth century, the owl represented (in the West, that is) “enlightened” wisdom: rational, inquisitive, skeptical, progressive.

The Romantic movement — a counter-Enlightenment fad that is still very much dominant in 2021 — intuitively understood how branding works. Small wonder, then, that Romantic philosophers, novelists, poets, and painters would during the first half of the nineteenth century mount a successful campaign to appropriate and subvert the owl-as-symbol-of-Enlightenment.

Concerned that Enlightenment, with its emphasis on science and individualism, had inflicted division and dismemberment upon humankind (a complaint one can read each and every week in New York Times op-ed columns by conservatives like Ross Doutht, David Brooks, and Bret Stephens), Romantic thinkers and artists depicted the owl as a symbol of alienation, befuddlement, and romantic as opposed to enlightened wisdom.

“When philosophy paints its gray on gray, then has a form of life grown old, and with gray on gray it cannot be rejuvenated, but only known,” muses Hegel in his preface to Philosophy of Right (1820). “The Owl of Minerva first takes flight with twilight closing in.” We can only gain wisdom in hindsight, suggests Hegel’s tenebrous, strigine metaphor. Not for this Romantic philosopher the 18th century’s metaphors about Enlightenment dispelling the darkness of superstition and ignorance. Wisdom is to be sought not at noonday but at day’s end; historically speaking, we can know nothing about the best way for humans to live together (contra Voltaire, Rousseau, Locke, Hobbes, Hume, et al.) until we’ve reached the turning point between a dying era and one not yet born.

Baudelaire’s 1857 poem “Les Hiboux” (The Owls), quoted below (in a 1952 translation by Roy Campbell that I particularly like) deploys the owl as a symbol of the pre-Enlightenment sage, a figure of intuitive — not rational — insight and understanding.

Sous les ifs noirs qui les abritent

Les hiboux se tiennent rangés

Ainsi que des dieux étrangers

Dardant leur oeil rouge. Ils méditent.[Within the shelter of black yews

The owls in ranks are ranged apart

Like foreign gods, whose eyeballs dart

Red fire. They meditate and muse.]

This is not Athena’s owl — it’s a less progressive symbol, a pagan symbol conveying a sense of romantic brooding, not ratiocination. Baudelaire is reactivating a pre-modern occult interpretation of the owl’s meaning.

Sans remuer ils se tiendront

Jusqu’à l’heure mélancolique

Où, poussant le soleil oblique,

Les ténèbres s’établiront.[Without a stir they will remain

Till, in its melancholy hour,

Thrusting the level sun from power,

The shade establishes its reign.]

Like Hegel, Baudelaire associates the owl with twilight — which, figuratively speaking, for the Romantics represented the forlorn hope that enchantment might return to the disenchanted modern world.

Leur attitude au sage enseigne

Qu’il faut en ce monde qu’il craigne

Le tumulte et le mouvement;L’homme ivre d’une ombre qui passe

Porte toujours le châtiment

D’avoir voulu changer de place.[Their attitude instructs the sage,

Content with what is near at hand,

To shun all motion, strife, and rage.Men, crazed with shadows that they chase,

Bear, as a punishment, the brand

Of having wished to change their place.]

Baudelaire concludes his poem on a warning note, suggesting that bourgeois types hustling and bustling about in the name of Progress (“this great heresy of decay,” as he puts it elsewhere) should learn from the wise owl, which — Romantically — prefers instead to quietly brood.

The Romantics, to sum up this section, didn’t attempt to suggest that the owl is not a symbol of wisdom. Instead, they suggested that the owl is a symbol of counter-Enlightenment wisdom; brooding rather than skeptical and sardonic, tranquil and meditative rather than proactive, progressive.

PS: Speaking of the occult, one of the more amusing theories about Illuminati symbolism hidden in the design of US currency is demonstrated above. The owl is a symbol of the Illuminati, one hears, because… reasons.

Confronted with the iconicity of the owl’s eyes, which lend it its appearance of sagacity, the Romantics seized upon the (fallacious) notion that owls can only see well at night… that the light of day dazzles them. The owl, according to this tradition revived in the nineteenth century, is masterful at night… but powerless, foolish by the light of day. Compare Baudelaire’s poem above with his poem about the albatross who, like the poet, is lord of its nonterrestrial domain (the sky) but once it touches solid ground — or a ship’s deck — becomes awkward and foolish.

“The Owles and Battes of our time, either can not, or will not see it.” — W. Fulke Heskins Parl. Repealed in D. Heskins Ouerthrowne (1579). “In heauenly things..more blind then Moales, In earthly Owles.” — J. Sylvester, tr. G. de S. Du Bartas Deuine Weekes & Wks (1605). “An owle-eyed buzzard, that by day is blind, And sees not things apparant.” — G. Wither, Abuses Stript (1613). These and other early-modern citations offer context to symbolic uses of the owl to represent overweening intellectuals and philosophers, who precisely because they are so expert at seeing the true nature of things are perplexed, stumbling and bumbling, in daily life.

It’s true that owls are farsighted. They can’t focus on objects that are too close; instead, sensitive whisker-like bristles around their beaks (“filoplumes,” they’re called) help owls detect objects at close range. They are not blinded by sunlight, though. Yes, they have a greater number of photoreceptor cells compared to human eyes, which gives them such excellent night vision… and which is affected badly by sunlight. However, they can compensate by closing their eyes halfway… and in doing so, they can see equally as well as we can during the day. This heavy-liddedness does make the owl appear sleepy, out-of-it, frowsy, befuddled, hapless.

One could happily research the owl, and gaze at owl-themed artworks and artifacts, for days on end. But let’s turn now to my second question: Why do some of us want to take the owl down a peg?

When we encounter an owl, as I used to do regularly at the Trailside Museum when hiking in the Blue Hills near Boston (both when I was a child, and later with my own children), will we feel awed or instead overawed — that is, intimidated, flummoxed, wrong-footed?

Here’s an off-the-cuff theory.

Awe is what highbrows and lowbrows alike feel when in the presence of a profoundly wise, apparently all-knowing figure.

The 1923 novel Bambi offers a lowbrow example:

Bambi enjoyed hearing the owl. She is so dignified as she flies, perfectly silent, perfectly effortless. A butterfly is quiet just because of her size, but the owl is so immense. And her face is so imposing, so determined, full of so much thought, her eyes are so majestic. Bambi admires her firm gaze with its quiet courage. He enjoys listening when she talked with his mother one time, or with anyone else. He stands slightly to one side, a little afraid of that imperious gaze he admires so much, he does not understand much of the clever things she says, but he does know that they are clever, and that enchants him, fills him with admiration for the owl.

Overawe, on the other hand, is a middebrow response. “I should be dumb before thee, feathered sage! / And gaze upon thy phiz with solemn awe,” apostrophizes the 19th-century middlebrow poet Henry Timrod. “But for a most audacious wish to gauge / The hoarded wisdom of thy learned craw.” Ugh.

In the presence of wisdom the middlebrow — who demands that every dose of medicine go down with a spoonful of sugar — feels less-than, challenged, put to some sort of test and found wanting. Which gives rise to what I’ve called Overawing Owl Syndrome. The mocking depictions of pompous, humbugging owls that I listed at the top of this post suggest that — at least since the Romantic Era — a kind of proxy war between middlebrow and wisdom has been raging in pop culture.

And middlebrow, much as I hate to admit it, rarely loses.

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.