This page will eventually list my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Nineties (1994–2003, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). This BEST ADVENTURES OF THE NINETIES list is a work in progress, and is subject to change. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

Once I’ve completed my research and reading for the Nineties, I’ll add an introductory note about what I enjoy and admire about this era’s adventure lit. For the moment, I’ll paste in something I’ve written elsewhere about what I don’t like about Eighties (and Nineties) adventure….

If the Eighties began in a good way with Neuromancer, they began in a shitty way with The Hunt for Red October — which, alas, was a vastly more popular and influential novel.

I haven’t enjoyed the post-1983 adventures I’ve tried to read by Tom Clancy. Not to mention those by: Robert Ludlum, Robert Jordan, or Robert Crais; James Patterson, James Redfield, James Rollins, or James Dashner; R.A. Salvatore, L.J. Smith, J.D. Robb, V.C. Andrews, J.R. Ward, P.C. Cast, or R.L. Stine; Scott Turow, Scott Westerfeld, Scott Bakker, or Orson Scott Card. Also: Jeffrey Archer, Dan Brown, Thomas Harris, Sue Grafton, John Grisham, Sidney Sheldon, Dean Koontz, Daniel Silva, Vince Flynn, Stieg Larsson, Gillian Flynn, Michael Connelly, Clive Barker, Greg Iles, Robin Hobb, Ted Dekker, Margaret Weis, Tess Gerritsen, Mark Z. Danielewski, Patricia C. Wrede, Christopher Paolini, Richelle Mead, Alexander McCall Smith, Stephenie Meyer, Matthew Pearl, Holly Black, Terry Brooks, Pittacus Lore, Jim Butcher, Angie Sage, Anthony Horowitz, Megan Whalen Turner, Gregory Maguire, Bernard Cornwell, David Baldacci, Mary Higgins Clark, Cornelia Funke, Tami Hoag, Lemony Snicket (except when illustrated by Seth), Alyson Noel, Brandon Mull, Tana French, Laurell K. Hamilton, Erin Hunter, Terry Goodkind, Rick Riordan, Kate Mosse, Jeff Lindsay, Christine Feehan, Neal Shusterman, Patricia Briggs, Veronica Roth, Joe Hill, Lee Child, Clive Cussler, Julie Kagawa, Harlan Coben, Lisa Gardner, Michael Scott, Ilona Andrews, William Paul Young, Cassandra Clare, and David Eddings.

Although I like (or sorta like) the pre-1984 writings of Frederick Forsyth, Stephen King/Richard Bachman, Robert Heinlein, Robert B. Parker, Robin Cook, Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, Stephen R Donaldson, Ken Follett, Lawrence Block, Mario Puzo, Anne Rice, Dick Francis, Michael Crichton, Frank Herbert, Isaac Asimov, Douglas Adams, Piers Anthony, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Jean M. Auel, Roger Zelazny, and Anne McCaffrey, their post-1983 adventures don’t do it for me.

I find it more difficult to identify 10 great adventure novels (or comics) from each year of the Nineties than it was to do so for earlier periods. But it’s not impossible! I’ve developed a preliminary list, and my research and reading continues apace. During 2020, I’m confident that I’ll be able to complete this page.

— JOSH GLENN (2020)

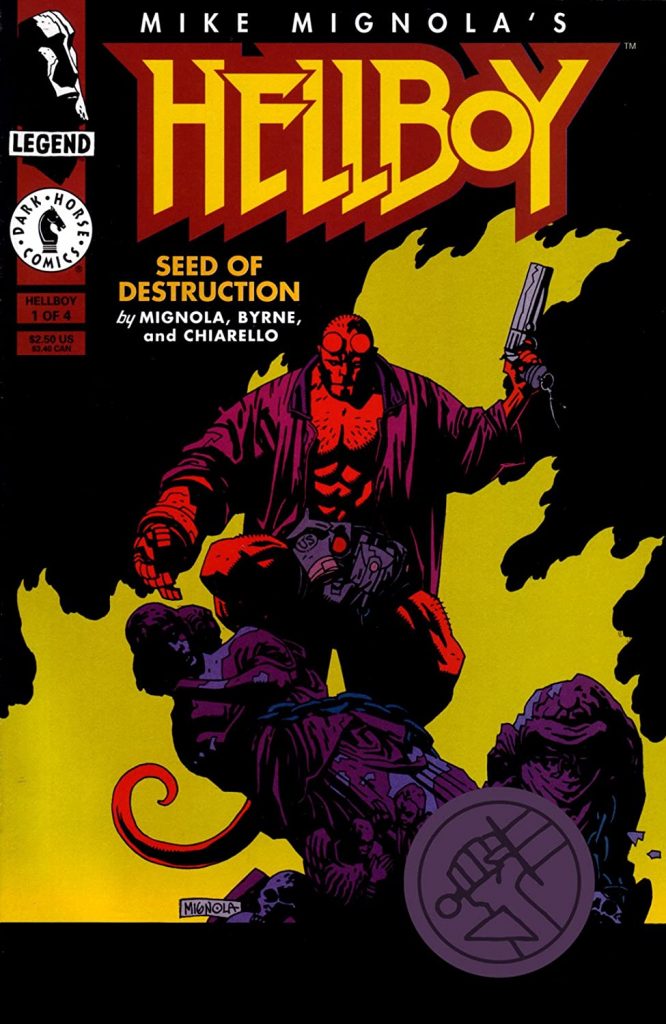

- Mike Mignola’s Hellboy comics (1994–present). The Dark Horse Comics story “Seed of Destruction” (serialized March–June 1994), written and drawn by Mignola with script by John Byrne, introduces us to one of the great comic-book characters of the era: the half-demon Hellboy. (Yes, there were one or two previous appearances, but here is where the Hellboy epic begins.) Summoned from Hell by Nazi occultists, then raised by Professor Trevor Bruttenholm, who after WWII would form the Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense (B.P.R.D.), Hellboy is a gruff, emotionally immature, but kind-hearted creature… whose grafted-on right hand is an apocalyptic demon-relic. He’s also the World’s Greatest Paranormal Investigator. Accompanied by a troubleshooting team of law enforcement officials, soldiers, mutants, and “scholars of the weird” (e.g., folkorist Kate Corrigan, the amphibian Abe Sapien, and the pyrokinetic Liz Sherman), Hellboy battles grotesque foes in a series of tall tales inspired by folklore, pulp magazines, Lovecraftian horror, and horror fiction. Mignola’s drawing style — thin lines, unwieldy shapes, a heavy use of black forms — has become iconic. Fun facts: Ron Perlman was an inspired casting choice for the 2004 and 2008 live-action Hellboy movies, directed by Guillermo del Toro. David Harbour’s performance in the 2019 reboot was also fun, but the movie wasn’t as good as the original two. The Hellboy character has also starred in animated films and three video games.

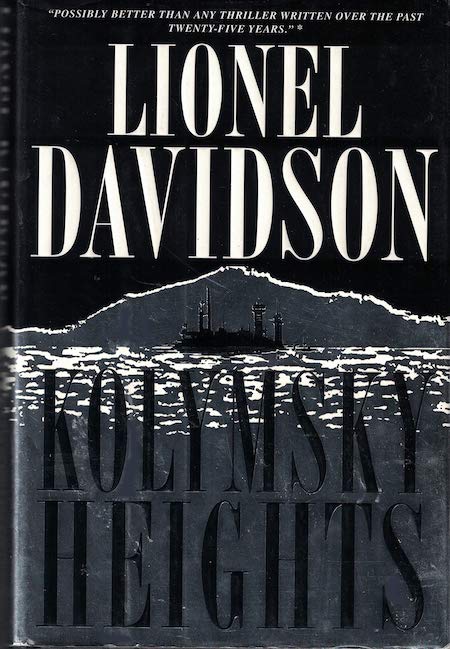

- Lionel Davidson’s espionage thriller Kolymsky Heights. After a 16-year hiatus from writing adventures for adults, Davidson returned with his final novel — a beautifully written, action-picked yarn to rival his best works, including The Rose of Tibet (1962), A Long Way to Shiloh (1966), and Making Good Again (1968). Dr. Johnny Porter, a Canadian professor of anthropology who has mastered the languages and dialects of the various tribes of Northern Canada, Alaska and Siberia, as well as Korean, Russian, and Japanese, is himself descended from Inuits — who remain physically, ethnically and culturally similar to their Siberian counterparts. He is, therefore, the only westerner who can hope to break into — and back out of — a Soviet scientific research base (ostensibly a weather station) in Siberia, one so secret that no one who enters is ever allowed to leave again. After receiving some training by the CIA, a reluctant Porter heads from Japan to Siberia disguised as a Korean sailor; this is only phase one of a multi-stage plan which will see our hero adopt multiple disguises, and survive by his wits. It’s a hunted-man story and man-agaist-nature story to rival anything by Buchan, Ambler, or Hammond Innes. Fun facts: Writing for The New York Times Book Review, James Carroll enthused that Kolymsky Heights — Davidson’s final novel — is “written with the panache of a master and with the wide-eyed exhilaration of an adventurer in the grip of discovery. Mr. Davidson has not only rescued one of the most familiar narrative forms of the era, the spy thriller; he has also renewed it.”

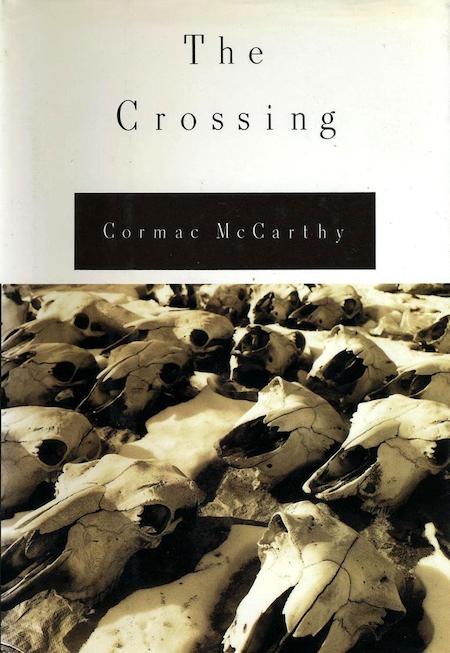

- Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy western adventure The Crossing. In the years just before and during WWII, teenage Billy Parham ventures across the New Mexico border into Mexico on three adventures — much like Walter Scott’s characters, impatient with over-civilized England, headed into the Scottish highlands. The first section, which has frequently been compared with Faulkner’s “The Bear” finds Billy communing with a wolf he’s trapped… and returning it to Mexico rather than killing it. When the wolf is taken from him and sold to a circus, where it’s going to be killed in a bloody spectacle, Billy makes one last — sacrificial — effort to protect its dignity. Returning home, Billy discovers that tragedy has befallen his family; springing his younger brother, Boyd, from a foster home, the two head back to Mexico to recapture their family’s horses. They rescue a Mexican girl with whom Boyd falls in love; they also end up in a bloody confrontation with a ranch chief who is unwilling to let them take their horses back. It’s a saga-like story, with no happy ending or uplifting moral; like Mark Renton in Irvine Welsh’s (also saga-like) Trainspotting, Billy learns only that most people live blunted, unfulfilling lives. The language and vocabulary, as always with McCarthy, is extraordinary. Fun facts: Billy’s story, as well as that of John Grady Cole, from All the Pretty Horses, continues in the final volume of the trilogy, Cities of the Plain (1998).

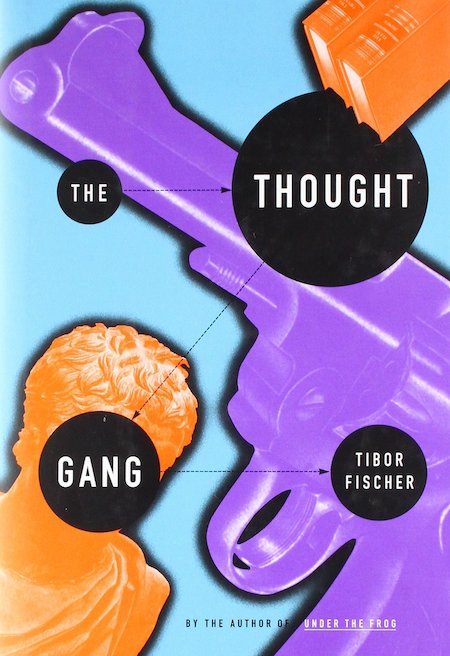

- Tibor Fischer’s crime adventure The Thought Gang. Eddie Coffin, an unemployed, alcoholic, sybaritic Cambridge philosophy professor, flees scandal in Britain for France; there, he meets Hubert, a one-armed (and one-legged) robber who’s recently been release from prison. Applying the metaphysical and existential insights of the great philosophers to the problems of bank robbery, the hapless duo embarks on a shambolic, mostly successful crime spree across the country. Eddie, one may be intrigued to hear, handles the robberies, while Hubert does the philosophizing. Fischer is not only a very funny writer, but a very erudite one; you’ll actually learn quite a bit about philosophy from this yarn… and you’ll marvel at his verbal pyrotechnics, not least his drive to incorporate words beginning with “z” into the narrative. (This is a plot device, not just a gimmick.) It’s all a bit too much, perhaps — but Fischer’s second novel is an utterly unique, highly entertaining story to which I’ve returned several times since it was published. Forget Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon’s sorta-funny foodie tours of the Continent; why hasn’t The Thought Gang been adapted as a TV series? Fun facts: Reviewers at the time tended to suggest that Fischer had lost control of his themes, while at the same time praising The Thought Gang in the highest possible terms — suggesting it was one of the funniest, most imaginative novels of the era. It deserves to be rediscovered by today’s readers.

- Jonathan Lethem’s sci-fi/neo-noir adventure Gun, with Occasional Music (1994). The author’s first novel is a pastiche of hardboiled crime fiction and cyberpunk; it’s affectionate towards the former, tongue-in-cheek towards the latter. In a not-too-distant future Los Angeles and Oakland, smart-mouthed private “inquisitor” Conrad Metcalf looks into the murder of Dr. Maynard Stanhunt, a prominent urologist who turns out to have been in cahoots with the gangster Danny Phoneblum. The victim’s ex-wife and the murder suspect’s sister are raising a “babyhead” — one of a cohort of infants whose development has been sped up, resulting in a Gen X-like subculture of cynical, unmotivated, whiny assholes. A thuggish evolved kangaroo (think Wilmer, the jumped-up “gunsel” from The Maltese Falcon) is tailing Metcalf, who’s got the hots for a sexy inquisitor with the unimprovable name Catherine Teleprompter. All these shenanigans take place in a dystopian America in which it’s all but forbidden to use words to describe news events; there’s a cultural taboo against asking questions; and everyone is on [the] Make, a legal drug that keeps users forgetful and contented. The inquisitors, who’ve settled upon a fall guy for the murder rap, subtract so many of Metcalf’s state-issued karma points that he may wind up doing time in the big freeze. But when Metcalf uncovers a scheme in which zero-karma convicts are implanted with “slaveboxes” and used as prostitutes (hello, Dollhouse), he plays it “existential. and maybe a bit stupid.” It’s the only way he knows how to play it. Fun fact: “I really, genuinely wanted to be published in shabby pocket-sized editions and be neglected — and then discovered and vindicated when I was fifty,” Lethem has said, about his early novels. “To honor, by doing so, Charles Willeford and Philip K. Dick and Patricia Highsmith and Thomas Disch, these exiles within their own culture. I felt that was the only honorable path.”

- Haruki Marukami’s apophenic adventure The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994–1995; in English, 1997). Toru Okada, a Bartleby-like slacker who lives in a Japanese suburb, has recently quit his tedious job and abandoned his dream of earning a law degree. His wife, Kumiko, is more ambitious and driven… but she has secret depths. Her brother, Noboru, a mediagenic academic who becomes a politician — and who is obsessed with Kumiko — is our shape-shifting antagonist. When Kumiko disappears, Toru embarks on a trippy, internal and external quest of discovery and self-discovery. If the way I’ve described this masterpiece of magical realism makes it sound like the Scott Pilgrim graphic novels, yes, it is sort of like that… except that it’s not about hipsters in the Toronto rock scene, and it’s not silly or shallow. I’d also compare The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle to Joyce’s Ulysses — the long digressions, the deep insights into the author’s national culture, and particularly the brilliant moments when a teenage girl’s POV takes over the story. Why did Kumiko leave? Did she ever love Toru? Who keeps calling Toru with mysterious leads and clues that make him more, rather than less confused? There are many interesting (mostly female) characters; a gripping war story related by an old soldier about his experiences in Mongolia during the Sino-Japanese War; and a bird whose mechanical-sounding cry punctuates the drama like a Greek chorus. Fun facts: Murakami, the most widely-read Japanese novelist of his generation, rejects the idea that he’s influenced by Kafka: “Kafka’s fictional world is already so complete that trying to follow in his steps is not just pointless, but quite risky, too,” he’s said. “What I see myself doing, rather, is writing novels where, in my own way, I dismantle the fictional world of Kafka that itself dismantled the existing novelistic system.”

- Iain M. Banks‘s sci-fi adventure Feersum Endjinn. Too many fans of Banks’s Culture series pooh-pooh this, his second non-Culture story — complaining in particular about the Riddley Walker-esque patois in which the character Bascule the Teller speaks. True, it’s not as fun as the Culture books… but like them it’s a staggering work of imagination, and a lot of fun. This one takes place in a vast, Gormenghastian castle-like structure known as the Fastness, around which the novel’s protagonists clamber like ants (one thinks of Aldiss’s Non-Stop), and also in the Cryptosphere, a vast dataspace that can be explored virtually, via avatar, and to which millions of personalities have been uploaded — but which is succumbing to entropy and chaos. Sessine, an assassinated military commander, wakes up in the Cryptosphere… only to be assassinated there, too; in this post-singularity future, we discover, a person can die several times, not only in the real world but virtually. We also encounter a top-ranked scientist, Hortis Gadfium, who is conspiring against the King; she is privy to new intel about an approaching catastrophe known as the Encroachment. Asura, a Leeloo-like figure, is tasked with activating the titular “fearsome engine” that will save the solar system… but she has amnesia; captured, she is subjected to a series of virtual-environment storytelling efforts to learn her secret. Meanwhile, Bascule, a Teller (whose job it is to project himself into the Cryptosphere in search of lost information), gets caught up in the political machinations and seeks refuge among chimeric animals. The final chase scene — involving a vacuum balloon ascending a space elevator — is terrific. And honestly, Bascule isn’t that hard to understand! Fun facts: “I used to have these model soldiers, and I wondered what it would be like to be one of those tiny soldiers in a giant house,” Banks would later explain in an interview. “I used to have these epic journeys for them. I thought if you had a giant structure, basing it on furniture would be easy.”

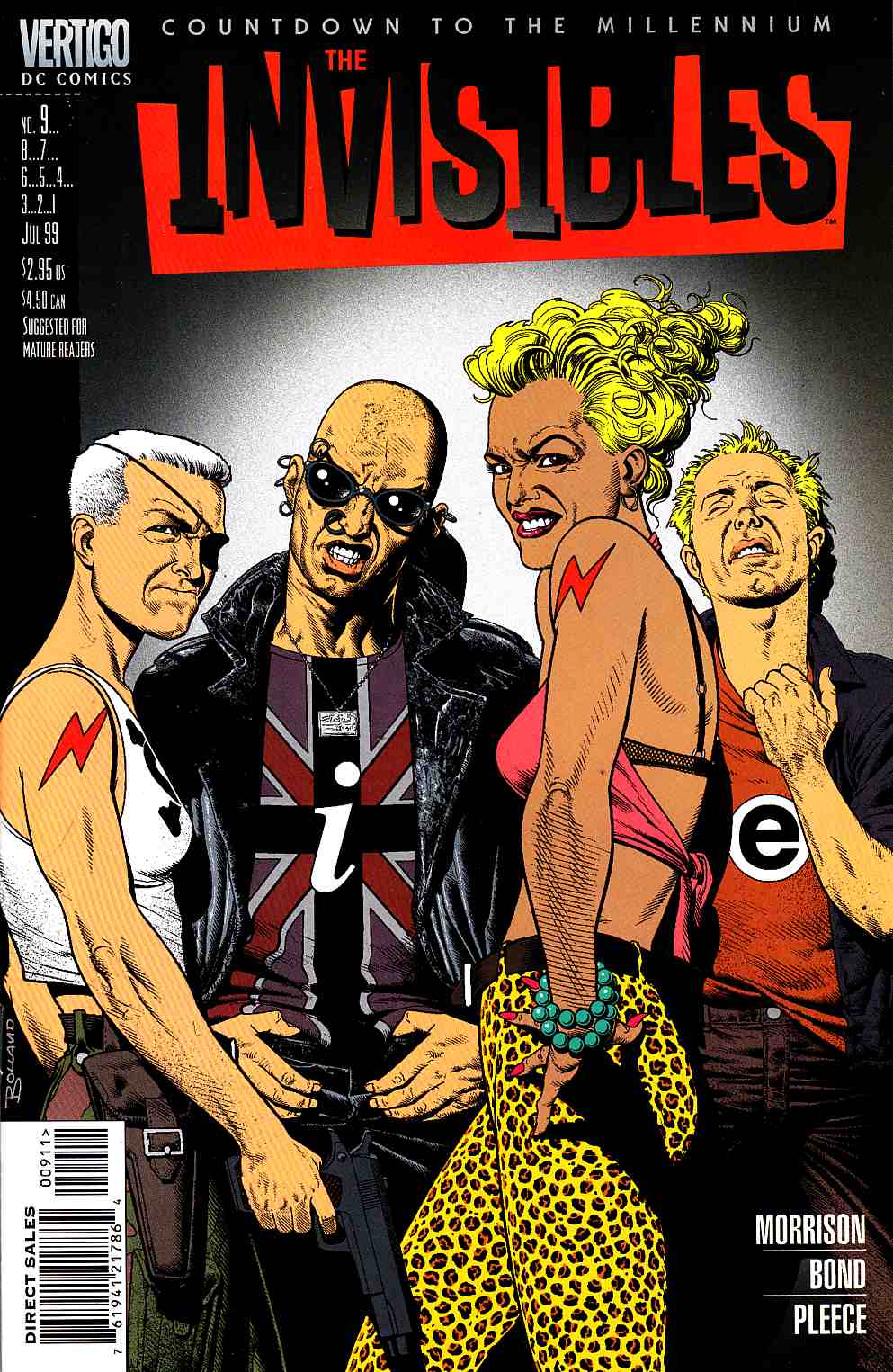

- Grant Morrison‘s comic The Invisibles (serialized 1994–2000). Scottish comic book writer Grant Morrison is one of the triumvirate of British creatives — along with Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman — whose trippy, subversive, meta-textual sensibilities helped mutate and transform American comics. A self-proclaimed chaos magician, Morrison gave us a world in which objective truth is unknowable, illusion and reality are interchangeable, “bad guys” are good and “good guys” bad. The Invisibles are group of transgressive, libertine, punk freedom fighters led by the Jerry Cornelius-like King Mob; they’re part of a larger organization, The Invisible College, which uses time travel, magic, and violence to battle the Archons of the Outer Church, interdimensional alien gods who’ve persuaded most of us to internalize their oppression. Other characters include: Lord Fanny, a transgender Brazilian shaman; Tom O’Bedlam, a homeless man; Boy, a former New York cop; and Ragged Robin, a telepath. In the first run of stories, the group recruits Jack Frost, a hooligan… who learns that he may be the reincarnation of the Buddha. The references — political, pop-cultural, sub-cultural — come thick and fast. A slow-moving adventure, richly rewarding. Fun facts: The Vertigo imprint of DC Comics published 59 issues of The Invisibles, in all. Morrison scripted the stories, and various artists illustrated them.

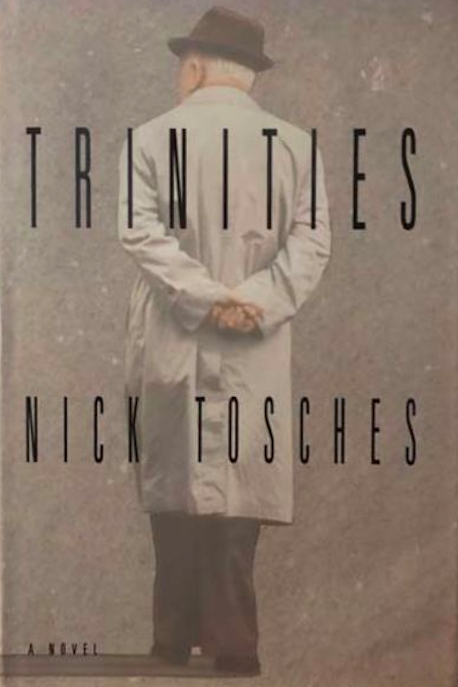

- Nick Tosches’s crime adventure Trinities. Before Tony Soprano, there was Johnny DiPietro — a Brooklyn-based Mafia hit man struggling with relationship problems, family loyalty, rival mafiosi out to betray or kill him, and morality. Through DiPietro’s eyes, we watch his uncle Joe — a grump, retired Mob boss who regrets having allowed the Chinese Triads to take over the heroin trade — cannily and ruthlessly get the gang back together. Joe’s Chinese counterpart, the aging Chinatown junkie and gang boss Chen Fang, is the second POV in Tosches’ unholy trinity; the third is that of D.E.A. agent Bob Marshall. We’re also introduced to several well-realized minor characters… most of whom die violently once war between the Mafia and the Chinese Triad gangs breaks out. Meanwhile, Johnny and his Uncle Joe are butting heads with the new Mafia leadership: young men with MBAs and an aversion to violence. Tosches is a fine story teller, one who takes the time to get into granular detail about everything from the most effective method of assassinating someone (and getting away with it) to cooking squid, laundering money, and using brand-name chemical products to cook up commercial quantities of China White. Fun facts: Tosches, who died in 2019, is best known as the tremendously talented author of such biographies as Hellfire: The Jerry Lee Lewis Story (1982), Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams (1992), and a journalist who covered music, the opium trade, and organized crime.

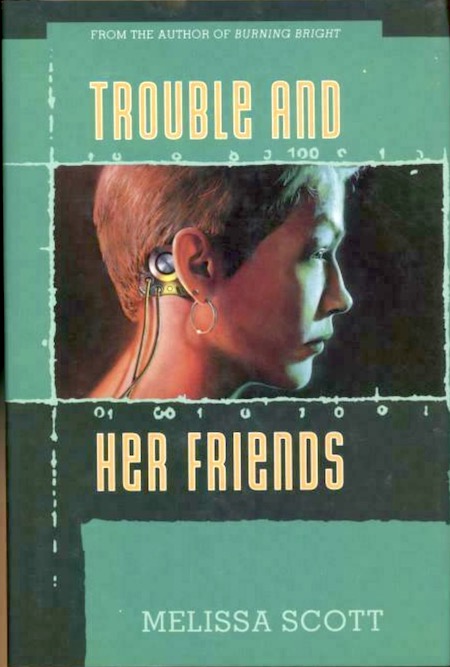

- Melissa Scott’s cyberpunk sci-fi adventure Trouble and Her Friends. At some point during the early 21st century, computer hacking — “cracking” — becomes as vigorously policed as burglary or bank robbery. So India Carless (a.k.a. Trouble), who’s one of the best crackers in the business, takes it on the lam. She leaves her partner, Cerise (a.k.a. Alice-B-Good), and their close-knit queer cracker group, for a legitimate career. (There’s a closing-of-the-frontier western vibe to this story.) Three years later, however, a cracker using her online identity, even her style of hacking, appears on the scene; pursued by her own employer, Trouble goes in search of answers. The interface that Scott describes — crackers use “dollie ports” and “brain worms” in order to feel physical sensations while navigating virtual reality — is intriguing; and I like how the narrative — as usual in cyberpunk — toggles between reality and VR. In what was an unusual move, at the time, Scott makes most of her characters queer women; they aren’t merely objects of desire for a male protagonist. On the other hand, Trouble and her friends — we learn from flashbacks — are the targets of proto-Gamergate sexism and misogyny. Despite her vanishing act, will Trouble’s community rally to help her out? Fun facts: Winner of the 1995 Lambda Literary Award for Gay & Lesbian Science Fiction and Fantasy. Scott would win this award again in 1996, for Shadow Man.

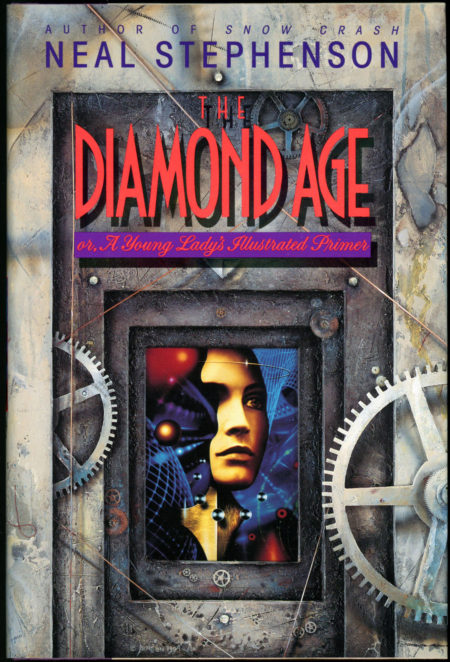

- Neal Stephenson‘s sci-fi adventure The Diamond Age: Or, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. When the designer of the Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer: a Propædeutic Enchiridion — an interactive story-telling device intended to inculcate in the granddaughter of “Equity Lord” Alexander Chung-Sik Finkle-McGraw the knowledge and skills to subvert the dominant paradigm — bootlegs a copy for his own daughter, it instead falls into the hands of young Nell, a bright 4-year-old slum-dweller. Under the tutelage of the Primer, Nell not only survives but thrives. Lord Finkle-McGraw, meanwhile, attempts to exploit Hackworth to advance the goals of his tribe; so does Dr. X, the Chinese engineer (and powerful Confucian leader) who’d helped Hackworth create the illicit Primer. Meanwhile, the actress Miranda, who provides the voice of the Primer and becomes a kind of surrogate mother to Nell, seeks the child out. All of this takes place against the backdrop of a Neo-Victorian British colonial society in which nanotechnology has made it possible for anyone to 3-D print food and objects, and government has become obsolete. The relationship between Nell and her Primer is an affecting one; in a sense, this is a book is a bildungsroman about homo superior — like Stapledon’s Last Men in London or Odd John, say, or Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder. However, in the book’s second half, the plot goes off the rails — with the introduction of tribes such as the Drummers, who create a subconscious hive mind through sexual orgies (is this a reference to Alan Moore’s Halo Jones comic?); the powerful CryptNet organization; and the Chinese Fists of Righteous Harmony. Stephenson’s goal is to explore the unintended consequences of a post-scarcity world… but the story ends abruptly and inconclusively. Fun facts: An enchiridion is a handbook; a propædeutic is a preliminary teaching, for beginners. Other fun fictional propædeutic enchiridions include Owen Hughes’s Arithmetic, Grammar, Botany & these Pleasing Sciences made Familiar to the Capacities of Youth, in Joan Aiken’s The Whispering Mountain (1968); and Huey, Dewey and Louie’s Junior Woodchucks’ Guidebook, from Carl Barks’s Donald Duck comics; the Junior Woodchucks first appear in 1951. PS: When my friends Elizabeth Foy Larsen and Tony Leone and I pitched the family activity book UNBORED to Bloomsbury, in 2010, we explicitly compared it to Stephenson’s Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer.

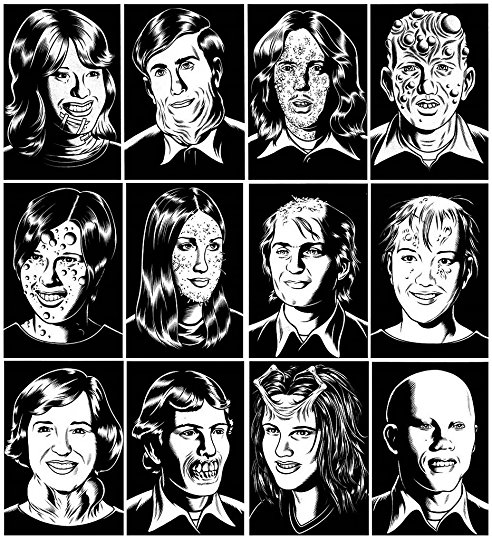

- Charles Burns‘s horror/sci-fi graphic novel Black Hole (serialized 1995–2005; in book form, 2005). I became aware of Charles Burns in the mid-1980s, thanks to his retro-sci-fi/horror “El Borbah” and “Big Baby” stories, which at the level of form may have paid tribute to the stylings of Will Elder, Hergé, and Chester Gould — but which were more sophisticated, in a surrealist, absurdist way. I was 28 when Kitchen Sink (Fantagraphics took over, later) began publishing the twelve installments that would make up Black Hole; I was 38 by the time the complete version was published. I mention this because my take on the story changed, during those years. A sexually transmitted disease mutates teenagers — over the course of a summer, in a suburb of Seattle, in the mid-1970s — into B-movie-esque monsters! The lucky ones are those who merely grow a little tail, or sprout chest-tendrils, or who shed their skin! Within this milieu, a lover’s triangle develops among Chris, Rob, and Keith; Keith, meanwhile, falls under the erotic spell of Eliza, a free-spirited artist living with dope dealers! Chris runs away, to live in the woods near her fellow freaks; but someone is killing them! When early issues of Black Hole appeared, I reveled in what I understood to be Burns’s nihilistic, body-horror take on, say, Dazed and Confused. However, by the time the last installment appeared, I looked forward not to finding out what happened next (for better or worse, it’s essentially a midcentury-style romance comic) so much as reimmersing myself in Burns’s fully realized world — gorgeous chiaroscuro, discontinuous chronology, teenage angst, sexual frustration and liberation… plus David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs. Wow! Fun facts: “There are certain truths that exist in genre fiction, even though it’s full of stereotypes and two-dimensional characters,” Burns said in an interview, once. “There’s a certain amount of unconsciousness that goes into genre fiction or genre movies. And out of that unconsciousness, I always see a certain kind of truth.”

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure Our Game. Tim Cranmer, an independently wealthy ex-Treasury boffin, has retired to his Somerset manor house and vineyard with his beautiful young lover, Emma. One evening, he is visited by police officers investigating the disappearance of Larry Pettifer, a professor at Bath University. Pettifer, we discover, had once been a British intelligence operative… and Cranmer was his handler and friend (frenemy, really) for twenty years. Pettifer and Emma had grown close, it seems, and Emma has also taken a powder. What’s more, Pettifer — a bohemian who’s never cared about money — has absconded with a large sum of money skimmed from British intelligence ops. Did the missing couple run away together? Or might Cramner have murdered his former protégé and romantic rival? Once Cramner uses his Cold War-honed skills to figure out what’s really happened, and bodies start turning up, the chase is on! Like Call for the Dead (1961), le Carré’s first novel, this one is both an espionage thriller and a murder mystery. In fact, I picture Cranmer as being much like James Mason’s character in The Deadly Affair, Sidney Lumet’s 1967 adaptation of Call for the Dead.…. Fun facts: The novel’s title refers to Winchester College football (known as Winkies, WinCoFo, or “Our Game”); Cranmer and Pettifer were Winchester schoolmates.

- Nicola Griffith’s sci-fi adventure Slow River. When we first meet Lore, the protagonist and sometime narrator of Slow River, she’s naked, injured, dumped to die by a kidnapper — whose true motivation we’ll only learn at the end. She’s taken in by Spanner, a charismatic female hacker and con artist; the two become lovers and co-conspirators, though eventually Spanner turns out to be not only untrustworthy but manipulative and amoral. Through flashbacks, we learn that Lore is the youngest child of the wealthy and powerful van Oest family — whose engineered bacteria provide clean drinking water in an age where untreated water is no longer potable. (We also learn that there’s a twisted secret at the heart of Lore’s family, one she only slowly figures out.) There are a few sci-fi gadgets — everyone has a personal ID chip inserted into their hand; everyone accesses the Internet via a “tablet” — but the technology of greatest import here is biotech, specifically related to drinking water. Like Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang, this story is a day in the life — many days in the life — of a talented but lowly worker, in a future industry. Although there are a few tense action scenes, it’s primarily a Robinsonade: We’re watching a smart, talented person solve problems. It’s also about overcoming privilege, and recovering from trauama. For some readers, this is boring stuff — “almost like a manual on water purification at times,” “her super power is being prodigiously good at sewage treatment management” — but I remained riveted. Fun facts: Winner of the Nebula Award for Best Novel, as well as the Lambda Literary Award — which is awarded annually to books which explore LGBT themes. Griffith also won a Lambda for her first novel, Ammonite (1993); since Slow River, four more of her books have also won a Lambda Award.

- José Saramago’s sardonic Robinsonade Ensaio sobre a cegueira (published in English as: Blindness). In this powerfully written anti-Cozy Catastrophe, when an unnamed city is plagued with an epidemic of “white blindness,” the afflicted are confined within an abandoned mental hospital to prevent them infecting others. One woman, known as “the doctor’s wife,” is spared from the blindness; we follow her efforts to protect her husband and their makeshift family — a boy with no mother, a girl with dark glasses, a dog — from the ruthless (though blind) mob which quickly assumes control over the hospital’s inmates. In doing so, our protagonist mustn’t let anyone realize that she can see. When the hospital’s micro-society — perhaps a Jack London-like metaphor for society’s underclass — erupts, and destroys the institution, its freed inmates discover that the outside world is devastated. The doctor’s wife and her group must now fend for themselves like castaways; their eyes are opened, if you will, to the perversities and injustice of life in a merciless capitalist social order. The book’s harrowing moral, if there is one, comes from our tough, compassionate, almost saintly heroine: “I don’t think we did go blind, I think we are blind, Blind but seeing, Blind people who can see, but do not see.” Fun facts: When Saramago was awarded the 1998 Nobel Prize for Literature, Blindness was one of his works praised by the committee. A 2004 sequel, which I haven’t read, is titled Ensaio sobre a lucidez. A 2007 adaptation by director Fernando Meirelles, starring Julianne Moore and Mark Ruffalo, isn’t great — but it has its moments.

- Octavia E. Butler’s Patternist adventure Clay’s Ark (1984). In the year 2021, a doctor named Blake and his teenage daughters are captured by Eli Doyle, the only survivor of Clay’s Ark, a spaceship that — upon its return from the first manned mission to Proxima Centauri — has crash-landed in southeastern California’s Mojave Desert. Infected with an alien microorganism that gives him heightened sensory and physical powers, but which compels him to transmit the infection to others via sexual contact, Eli has isolated himself on an isolated ranch… where he and others whom he’s captured (all of whom have been altered, by the microorganism, in ways that allow them to survive and thrive) are raising their sphinx-like offspring — intelligent quadruped mutants who perceive uninfected humans as food, and who can spread the microorganism through their bite. Society, meanwhile, has devolved into armed enclaves, marauding “car families,” and other post-apocalyptic phenomena. Blake and his daughters must decide whether to resign themselves to living within Eli’s enclave… or escape, and risk not only being captured by even worse predators, but aso creating an uncontrollable epidemic that could forever transform humankind. Though written last, Clay’s Ark is chronologically the third in the Patternist series. Fun facts: With the exception of Kindred in 1979, all of Butler’s earlier books are set in the Patternist universe. The first Patternist installment, Patternmaster, was published in 1976.

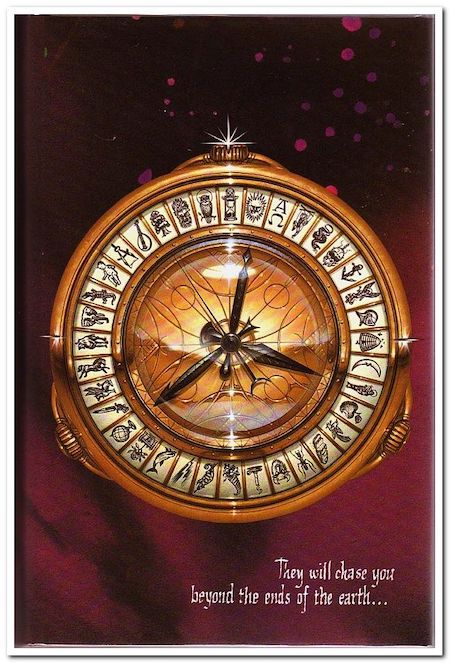

- Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials fantasy adventure Northern Lights (also published as The Golden Compass). In a universe parallel to our own, the world is dominated by the Magisterium, a Catholic Church-like global religious institution intolerant of heresy. Charmingly, in this world human souls exist outside of their bodies in the form of “dæmons,” protective spirits who take the form of animals. The dæmons may have something to do with mysterious elementary particles, or “Dust,” scientific investigations into the nature of which the Magisterium dissuades. When Lord Asriel, a swashbuckling scientist planning a journey to the Arctic in order to study the (possible extra-dimensional) origin of Dust, is nearly incapacitated or murdered by an agent of the Magisterium, his 12-year-old niece Lyra — a bright but semi-feral child raised by the scholars of Oxford — is determined to assist him in his quest. Child abductors known as the “Gobblers” abduct Lyra’s friend Roger, and Lyra is taken under the wing of a Mrs. Coulter — a Magisterium agent and, we learn, head of the Gobblers. Soon, a fugitive Lyra is headed north in the company of nomadic ’Gyptians; on her journey, she will encounter witches, a talking polar bear, and an aeronaut. It’s a fun thrill-ride, one guided by Lyra’s reading of an “alethiometer”…. Fun facts: The novel’s alternate title is not a reference to the alethiometer, but to the drafting compass that God used to establish the boundary of all creation in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Northern Lights, which was awarded a Carnegie Medal, was adapted as a 2007 movie featuring Nicole Kidman, Dakota Blue Richards, Daniel Craig, and Sam Elliott; the BBC’s 2019 TV adaptation looks superior. PS: I don’t love the other installments in the His Dark Materials series, I’m sorry to report.

- Ken MacLeod’s Fall Revolution sci-fi adventure The Star Fraction. In a balkanized Britain just a few hundred years from now, Moh Kohn, a smartgun-brandishing Trotskyist mercenary, finds himself embroiled in a revolution against the US/UN — a meta-dictatorship which made itself the neutral arbiter of international security in the wake of World War Three. The US/UN does not rule directly, but instead enforces a set of (sometimes secret) laws over a vast number of global microstates; for example, certain avenues of research, such as intelligence augmentation or artificial intelligence, are prohibited. The revolution, it seems, was set into motion by the Watchmaker, a financial software that may have evolved into an AI — thanks to the illicit work of Janis Taine, a scientist working on memory-enhancing drugs. Along with Janis and Jordan, a teenage atheist and hacker from a fundamentalist Christian microstate, Moh must evade the US/UN’s spy satellites — while navigating the violent squabbles of communists, socialists, libertarians, and anarchists. The book, which is replete with Marxist puns and in-jokes, is a throwback to cyberpunk: interfacing technology, biological enhancements, mind-altering drugs, a vibrant underworld. If the plot is too frenetic, and the characters underdeveloped, that’s OK — it’s the author’s first outing. I don’t understand it, but I enjoy it. Fun fact: MacLeod, a Scottish author, continued the Fall Revolution series with The Stone Canal (1996) and The Cassini Division (1998). The Sky Road (1999), meanwhile, represents an alternate sequel to The Stone Canal.

- Jonathan Lethem‘s sci-fi adventure Amnesia Moon. A post-apocalyptic picaresque, set in a fragmented future America in which the world as we know it has ended… subjectively speaking. Chaos, whose name may also be Everett Moon, or something else altogether, lives in an abandoned megaplex in Wyoming. Because his dreams are colonized by the more powerful dreams of Kellogg, an irreverent local guru and not-so-strong strongman, Chase hits the road — accompanied by Melinda, a fur-covered young girl. They visit an area covered in a thick green fog, save for an exclusive private school; and a Californian town that has converted to a luck-based social system. There are overt and covert meta-textual references to works by Philip K. Dick, Cornell Woolrich, Jack Kerouac, and Wim Wenders; at one point we hear of a West Marin inhabitant named “Hoppington,” a shout-out to the mutant telepath villain of Dick’s Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb. Televangelists in San Francisco have become robots, soap operas star government figures, Los Angeles is overrun by aliens! Along the way, Chaos learns more about his own past, and his own abilities. The narrative thread holding these excursions together is the notion that, in this post-whatever-happened world, reality is shaped — locally, even parochially — by those few individuals able to influence those around them to subscribe to their own subjective worldview. Fun fact: In interviews, Lethem later explained that Amnesia Moon is “a fix-up of unpublished short stories. I was trying to write out an obsession with dystopias, with collapsed or oppressed realities. At some point, I took a step back and said, ‘What am I trying to do here? Why are all the stories similar?’ The genesis of Amnesia Moon is my conclusion that what they had in common was this kind of need on the part of the characters, and apparently the author, to have the world destroyed.”

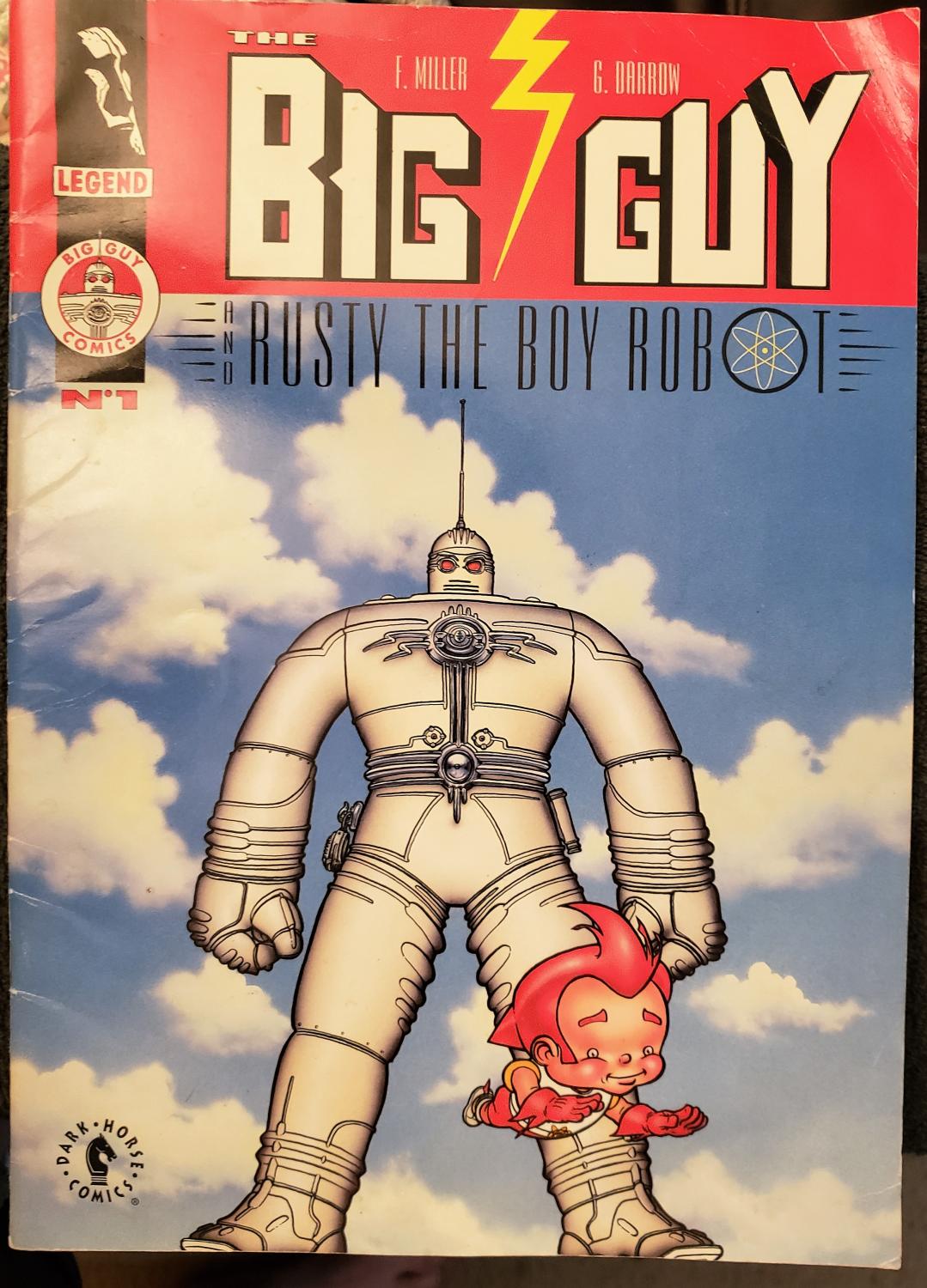

- Frank Miller and Geof Darrow’s comic The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot (serialized July-August 1995). Perhaps my favorite example of Geof Darrow’s work, The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot is a large-format pastiche of midcentury kaiju movies and Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy manga. As for Frank Miller’s story and script, it’s thrilling… but problematic, too, insofar as we can’t quite tell whether we’re supposed to laugh at the retro American triumphalism or applaud it. The Big Guy is an aircraft carrier-housed American WMD; Rusty the Boy Robot is his Japanese — more efficient, cuter — replacement. (Think WALL·E and EVE in WALL·E, or perhaps Burt Reynolds and Jan-Michael Vincent in Hooper.) When a Japanese experiment with primordial ooze goes wrong, and a giant reptilian creature begins to destroy Tokyo — and transform its citizens into monsters — Rusty springs into action, but fails to defeat the menace. Enter the Big Guy, who kicks ass while spouting American can-do homilies; squeamish readers might suspect that Miller is trolling us with this scenario, in which a Hiroshima-like event is Japan’s fault, and America plays the role of global peacekeeper. At the level of form, however, The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot is dazzling — epic in scale, yet incredibly detailed down to individual bullet shells and chunks of concrete. It’s a fucked-up masterpiece. Fun facts: The Big Guy first appeared in scattered pin-up and poster pages, before making a couple of appearances in Dark Horse’s Madman comics. The two-part comic reviewed here was adapted as a 1999–2001 animated series featuring Pamela Adlon as the voice of Rusty, and Jonathan David Cook as the voice of the Big Guy.

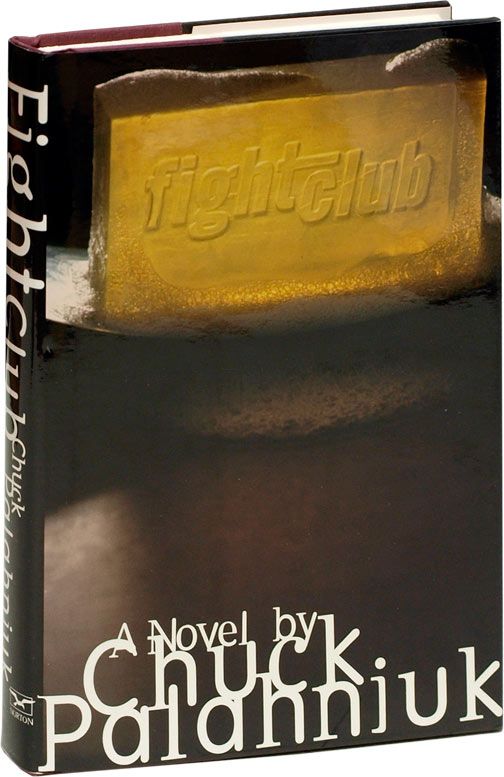

- Chuck Palahniuk’s atavistic/apophenic adventure Fight Club. Liberated by insomniac perceptivity, our unnamed protagonist, who works as a product recall specialist for a car company, begins to see his life for what it really is: a joyless, meaningless, consumerist nightmare. Into this void steps a charismatic, self-radicalized figure — Tyler Durden — who cheers on our narrator’s efforts to blow up his own life. The two men start an underground, bare-knuckle “fight club” whose brutal rules and cultish secrecy attract a coterie of desperate wage slaves. Around the same time that the mythopoetic men’s movement was encouraging men uncertain of their masculine identity to form drum circles, etc., the characters in Fight Club pursued a far more radical program of heteronormative, masculinist therapy. (Reading the book in 1996, I appreciated it as a sardonic critique of all efforts to recover a pre-industrial conception of masculinity through camaraderie; today, I’m disturbed by the notion that some readers may have taken it seriously. Note that the pejorative term “snowflake,” meaning someone who naively believes that they deserve undue success and recognition, comes from this novel.) Things get weirder. The novel’s one female character, Marla, is never in the same place at the same time as Tyler… are they somehow, one and the same person? The fight club turns into Project Mayhem, an organization dedicated to sabotaging and ultimately destroying, you know, the system. It’s a punishing read, really — but what a surprise ending. Fun facts: Adapted in 1999, by David Fincher, as a movie starring Edward Norton as the protagonist and Brad Pitt as Tyler Durden. Although the movie was a box-office flop, it found commercial success with its DVD release and is now considered one of the era’s defining cult classics. Palahniuk wrote two (meta-)sequels, both in comic-book form.

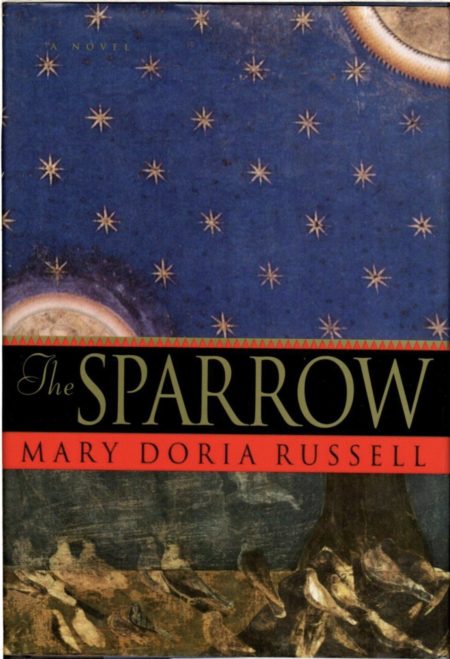

- Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow sci-fi adventure The Sparrow. In 2019, a SETI listening post in Puerto Rico picks up radio broadcasts of exquisite singing — coming from another planet. At last! Evidence of intelligent extraterrestrial life. While the United Nations debates the politics of a first-contact mission, the Jesuits, long known for their missionary, linguistic and scientific activities, organize a secretive first expedition to Rakhat — as the planet comes to be known. Only one member of the crew, Jesuit priest and talented linguist Emilio Sandoz, survives the return trip (in 20160). Its story — told in chapters that alternate between an account of the mission itself, and Sandoz’s experiences upon his return — about a world so beyond comprehension that it begs the question of what it means to be “human.” The characters — including Sandoz, who grew up in a poor Puerto Rican neighborhood, and who questions his faith; Sofia Mendes, a Turkish Jewish artificial intelligence specialist; and other Jesuit priests — encounter two species, upon their arrival at Rakhat. As missionaries and anthropologists will do, they get involved in the local culture in ways which they don’t understand… the result is lethal, and for Sandoz extremely traumatic. Fun facts: Russell earned a Ph.D. in Paleoanthropology, and has studied cultural and social anthropology. The Sparrow, which was the author’s first novel, and its 1998 sequel Children of God, explore the problem of evil, and how to reconcile a benevolent deity with human suffering. (The title refers to Matthew 10:29–31, “Yet not one [sparrow] will fall to the ground outside your Father’s care.”) The Sparrow won the Arthur C. Clarke and James Tiptree, Jr. Awards.

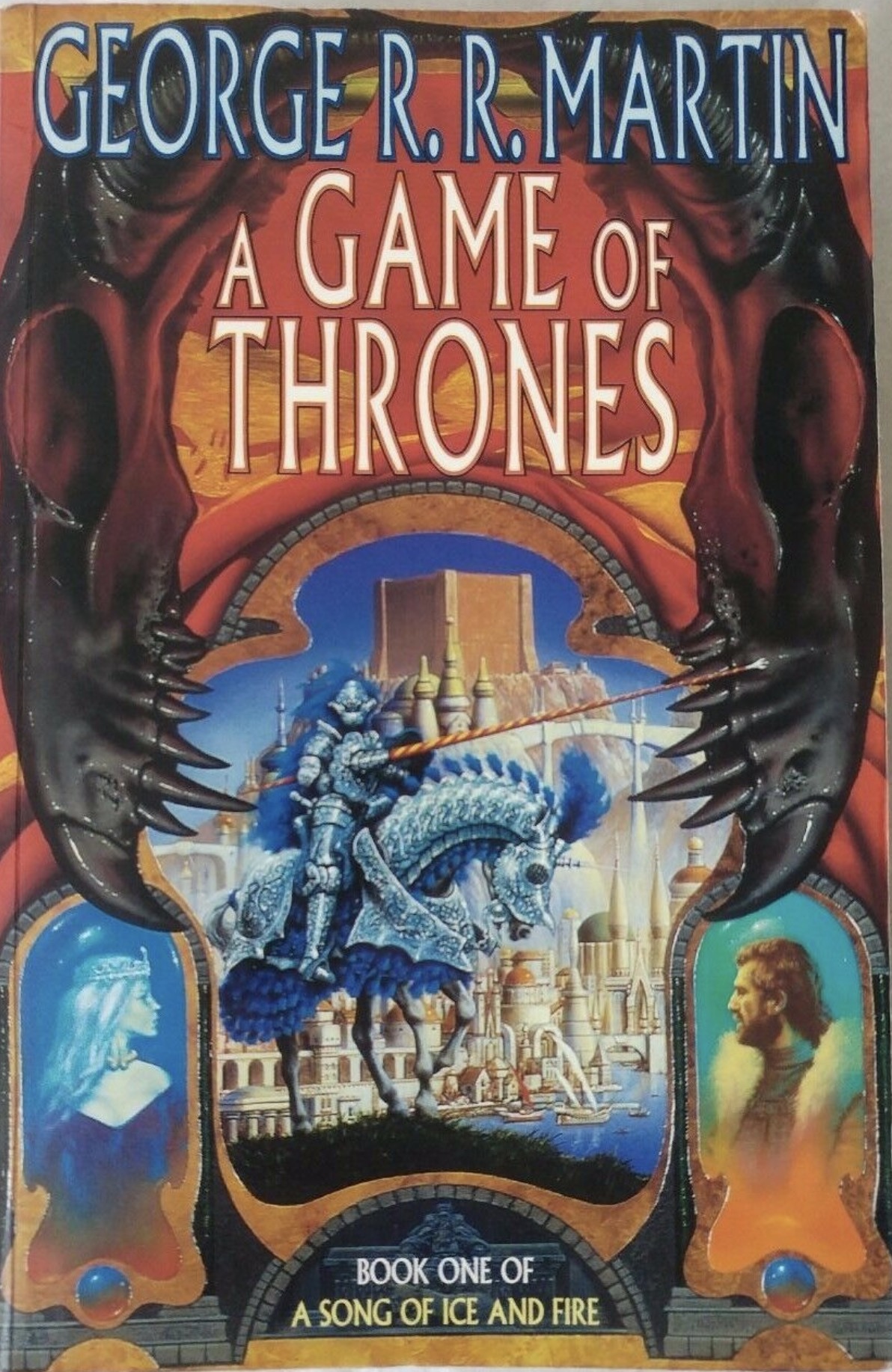

- George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire fantasy adventure A Game of Thrones. In the first installment of Martin’s epic fantasy series (1996–ongoing), we are introduced to a War of the Roses-esque dynastic struggle among the great Houses of Westeros, the central characters being the usurper Robert Baratheon, his childhood friend Ned Stark, Robert’s scheming wife, Cersei Lannister, and Cersei’s cunning, witty, self-indulgent brother Tyrion; Ned’s wife and children are also viewpoint characters. Ned’s illegitimate son, Jon Snow, meanwhile, joins the Night’s Watch — an order of warriors who guard the far northern borders, not only from the wildlings who live beyond The Wall, but from a fabled and hostile inhuman race, the Others. As if this weren’t already complex enough, a third plot-line concerns Daenerys, heiress to the Targaryen throne which King Robert had seized. In this first book, there are assassinations, executions, and political machinations aplenty in Westeros; mysterious doings north of the Wall which suggest that “winter is coming”; and poor Daenerys is married off (by her ruthless brother) to Khal Drogo, warlord of the nomadic Dothraki, in exchange for the use of Drogo’s army to reclaim the throne of Westeros. Oh, and dragons — long thought to be mythical or extinct — make a comeback. Fun facts: Blood of the Dragon, comprising the Daenerys chapters from A Game of Thrones, won a Hugo for Best Novella. The violent, raunchy 2011–2019 HBO adaptation of the series, starring Sean Bean as Ned Stark, Lena Headey as Cersei Lannister, Emilia Clarke as Daenerys Targaryen, Jason Momoa as Khal Drogo, and Peter Dinklage as Tyrion Lannister, did not disappoint fans… except for its ending.

- Iain M. Banks‘s Culture sci-fi adventure Excession. The fifth Culture novel concerns the response of the Culture’s Minds — benevolent AIs with enormous intellectual and physical capabilities — to the so-called Excession, a black-body sphere which appears mysteriously on the edge of Culture space… and which appears to be older than the Universe itself. The Affront, a rapidly expanding intergalactic empire, whose sadistic brutality is horrifying to the Culture, seeks to claim control of the Excession. The Interesting Times Gang, an informal group of Minds tasked with preparing for and confronting Outside Context Problems (challenges utterly outside the Culture’s experience), steps in; their conversation — a rich stew of numbers, text, esoteric syntax, and witty repartee — is a delight. The Sleeper Service, a Mind housed in a GSV (General Systems Vehicle), which 40 years earlier had separated from the Culture proper, is pressed into service; Genar-Hofoen, a human Culture diplomat to the Affront, and his ex-lover, Dajeil, are also dragged into the adventure. The story is slow to develop, but in the end we discover that the Sleeper Service is a very impressive Mind, indeed. And if those of you who’ve read Banks’s The Player of Games (1988) suspect that Special Circumstances was playing a deep game, vis a vis the Affront, you’re right. The true role of the Excession, meanwhile, is cosmic and mind-blowing — a conceit worthy of Kirby himself. Fun fact: In an interview with the magazine SFX, Banks credited Sid Meier’s 1991 strategy videogame Civilization — in which players begin at the dawn of humanity, and pursue new technologies while building an empire — with this novel’s notion of Outside Context Problems. “You’re getting along really well and then this great battleship comes steaming in and you think, well my wooden sailing ships are never going to be able to deal with that.”

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure The Tailor of Panama. In this unusually light-hearted le Carré novel, Andy Osnard, an unscrupulous Thatcherite MI6 agent sent to Panama City to gather intelligence, seems to draw inspiration from Graham Greene’s darkly comedic 1958 spy novel Our Man in Havana, in which a vacuum-cleaner salesman sells made-up military intelligence to MI6. Discovering that Harry Pendel, a successful tailor and British expat, has something to hide, Osnard coerces him into a scheme involving a fictitious network of revolutionaries known as the silent opposition. (This detail could be read a nod to another Greene novel, The Quiet American.) Harry’s invented stories wind up getting his friends into hot water; his wife, meanwhile, discovers what’s been going on. In the end, the UK and US governments must decide whether to use Harry’s fantasies as an excuse to invade Panama and topple the government…. This one is not every le Carré fan’s cup of tea, but I find it comical and poignant. Fun facts: John Boorman directed the 2001 adaptation, making the excellent decision to cast Geoffrey Rush as Pendel, and Pierce Brosnan — in a gleefully wicked performance subverting the work he was doing simultaneously in the James Bond franchise — as Osnard.

- Ken MacLeod’s Fall Revolution sci-fi adventure The Stone Canal. If the politics and economics — there’s a near-future crisis of global capitalism, which gives rise to a variety of competing social orders — of the first Fall Revolution installment, The Star Fraction (1995), confused you, then The Stone Canal may clear things up. Set in the same post-Singularity Solar System, MacLeod’s second novel takes place in 20th-century Scotland, but also in 21st-century ShipCity, the capital of New Mars — a colony world and technopolis at the other end of a wormhole created by the “fast folk,” uploaded human intelligences. The story’s interwoven strands each concern Jon Wilde and Dave Reid, politically radical frenemies whose lives take them in different directions. Reid becomes the right-libertarian leader of New Mars; Wilde remains a left-libertarian political activist. Wilde gets the girl — Annette, but Reid constructs a female sex-slave android version of her… who becomes self-aware and flees. Wilde, meanwhile, finds his mind downloaded into a clone; he’s been revived by Jay-Dub, a version of himself stored within a “human equivalent” robot! Reid, it seems, is the villain whose machinations led to WWIII… but Wilde may not have been entirely blameless. A luta continua. There are thrilling action sequences, and amost-as-thrilling political discussions, galore. Fun facts: The Stone Canal won a Prometheus Award. In an interview, MacLeod later explained that he was reacting to what he saw, at the time, as “the loss of any sense of common interest and common cause, and a descent into nationalism and identity politics all of which were supervised and policed from above – sometimes literally — by state and supra-state power.”

- Margaret Atwood’s historical psychological thriller Alias Grace. Written in what’s been described as the Southern Ontario Gothic style (think Alice Munro, Robertson Davies), Alias Gracerecounts the true-crime story of Grace Marks — an uncommonly pretty housemaid who in 1843 was convicted for her involvement in the vicious murder of her employer, Thomas Kinnear, and his mistress/housekeeper, Nancy Montgomery. Several years later, Grace — who claims to remember nothing about the incident — is hired as a domestic servant in the home of the penitentiary governor. Dr. Simon Jordan, a young psychiatrist, is called in to interview the notorious woman, in an effort to determine whether she was a murderess or merely an unwilling accomplice. Grace recounts her life story — as a struggling, abused Irish immigrant to Canada — to Jordan, who doesn’t see her story as relevant. Jordan, meanwhile, is an eligible bachelor uninterested in the vapid society women into whose company he’s forced; he’s attracted, instead, to his married landlady… and perhaps to Grace, as well. Atwood’s story includes newspaper blurbs, extracts from Grace’s written confession, poems, and more. Poverty, servitude, violence, insanity — this is a dark, mesmerizing tale. Fun facts: Adapted as a 2017 Canadian TV miniseries directed by the great Mary Harron, Alias Grace stars Sarah Gadon as Grace Marks.

- Peter Doyle’s Billy Glasheen crime adventure Get Rich Quick. A highly entertaining caper novel set in Australia’s rock’n’roll underworld of 1957. Billy Glasheen, a small-time hustler and sometime musician, is the mastermind of elaborate capers… which somehow always fall afoul of Sydney’s bent cops, organized criminals, and scheming politicians. Little Richard, Gene Vincent, and Eddie Cochran are touring the country, promoted by Lee Gordon — the real-life entrepreneur whose tours had a major impact on the Australian music scene at the time. Glasheen wangles himself a job working as Gordon’s chauffeur, gofer, and provider of illicit substances; Australian rock’n’roller Johnny O’Keefe also plays a role. But when Billy is framed for murder, he takes it on the lam. In order to prove his innocence, he’ll have to find the real killer. The period Aussie slang — bodgies, widgies, etc. — is a treat. Doyle would go on to write two sequels, Amaze Your Friends (1998) and The Big Whatever (2015), and a prequel, The Devil’s Jump (2001), which collectively form an epic, neo-noir tale of Australian crime, political scandals, and musical subcultures. Fun facts: Winner of Australia’s prestigious Ned Kelly Award for Best First Crime Novel. Doyle, a HILOBROW friend, is perhaps best known as a musical and true-crime historian. His books City of Shadows: Sydney Police Photographs, 1912-1948 (2005), Echo and Reverb (2005), and Crooks Like Us (2009) are extraordinary.

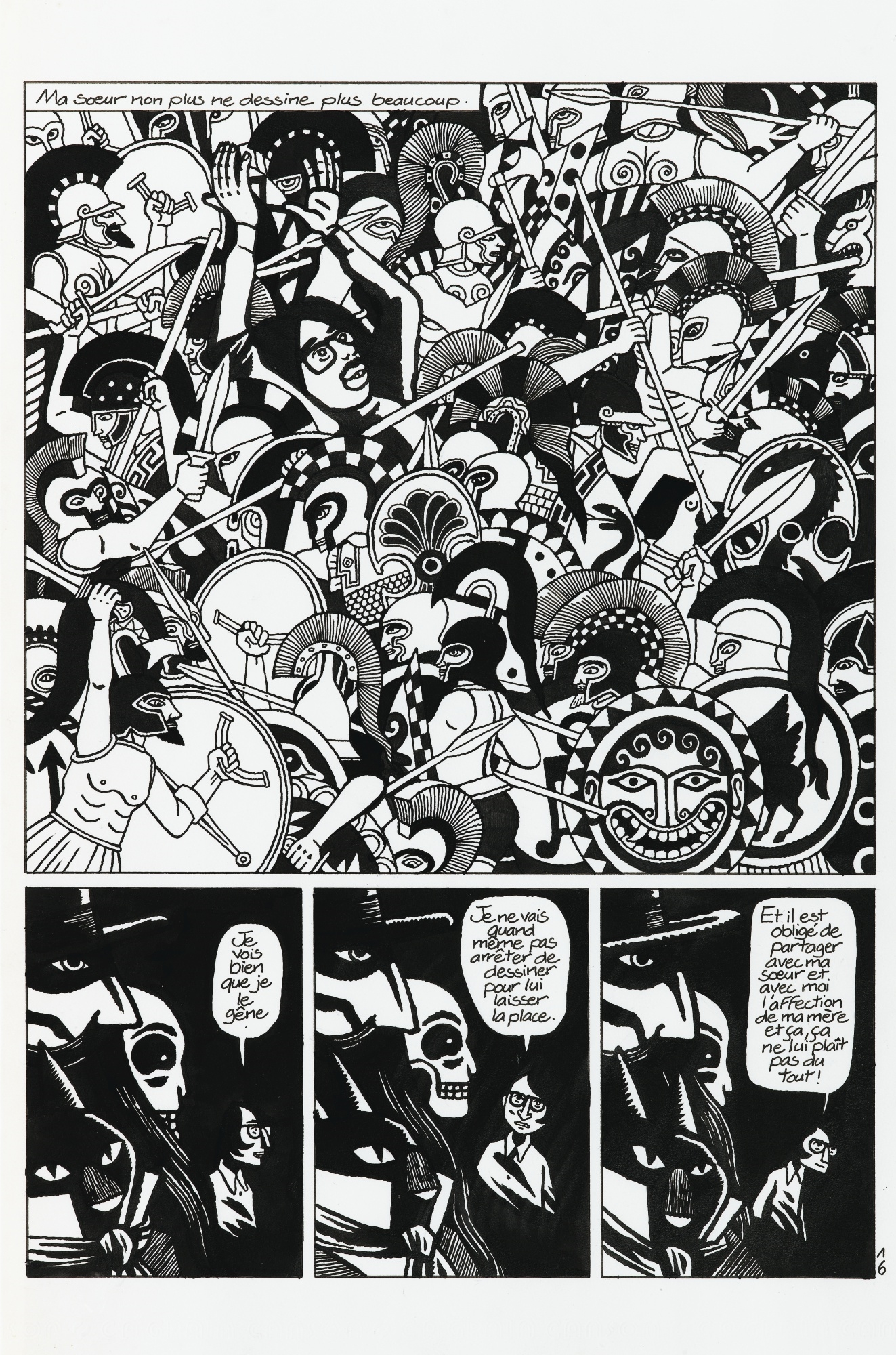

- David B.’s graphic novel L’Ascension du haut mal (in English: Epileptic, serialized 1996–2003). An autobiographical account of the influence that his brother Jean-Christophe’s epileptic seizures had on the author’s developing imagination. Dragged from guru to guru by his parents, who during the 1960s–1970s explored psychology, macrobiotic communes, acupuncture, magnetism, and more in an effort to cure Jean-Christophe’s malady, Pierre-François (who’d change his name to David) escapes into violent, redemptive fantasies involving epic battles between samurai, knights, and demons. David B.’s black-and-white artwork is epic in scope, like psychedelic Greek urn paintings; the autobiography isn’t an adventure, but Pierre-François’s dream life certainly is. War, conspiracies, the irruption of fantasy into reality, golems, monsters… it’s an extraordinary achievement. There’s a little bit of everything, here — family history, the French Resistance, Algeria, May’68. We empathize with the author, even if we can’t wholly sympathize with him; he portrays himself as a self-centered, even cruel sibling. Readers seeking an uplifting account of life with an epileptic family member will be disappointed, perhaps even horrified. It’s not uplifting, though it is mesmerizing. David B.’s perspective is that of a recording angel: horrified, sardonic, forgiving. Fun facts: Haut mal is an archaic term for epilepsy meaning “great illness,” or literally, “high evil.” Serialzed in six bande dessinée albums between 1996 and 2003, then compiled in 2005 into one 360-page graphic novel. David B., who was instrumental in encouraging Marjane Satrapi to create Persepolis, won the 2005 Ignatz Award for Outstanding Artist for his work on the series.

- William Gibson‘s Bridge sci-fi adventure Idoru. The sequel to 1993’s Virtual Light removes us from San Francisco. Fourteen-year-old Chia (as in Chia Pet) McKenzie, a superfan of the rock duo Lo/Rez, is selected by her fanclub to travel to Tokyo. There, she meets with the club’s Tokyo chapter, in hopes of learning what’s going on with the rock star Rez… who claims that he plans to marry Rei Toei, an artificial intelligence which presents itself as a female pop-star hologram. Chia never truly groks Rez’s bizarre, impossible marriage scheme, and neither do we; however, Rei — the titular idoru (Japanglish for idol) is one of Gibson’s more entertaining and fascinating characters. En route, Chia gets mixed up with scary members of the Russian Mafia, who are attempting to get their hands on a highly illegal nanotech assembler; she is assisted in her escape efforts by Masahiko, a young otaku (computer geek) who is a member of the “Walled City,” a virtual community of hackers with impressive skills. We also encounter “netrunner” Colin Laney, a more typical Gibson protagonist; he is a Friday-esque mutant able to intuitively recognize patterns of probability when surfing massive amounts of data via virtual-reality goggles. Shinya Yamazaki, an existential sociologist, and Keith Blackwell, head of Rez’s security team, are also entertaining characters. All parties eventually converge at a Tokyo love hotel, where otaku hackers and Lo/Rez fangirls team up — online and off — in order to save Rei Toei, and the day. Fun facts: In a 1999 interview, Gibson remarked: “Laney’s node-spotter function is some sort of metaphor for whatever it is that I actually do. There are bits of the literal future right here, right now, if you know how to look for them. Although I can’t tell you how; it’s a non-rational process.”

- Thomas Pynchon’s historical frontier adventure Mason & Dixon. In 1761, in an ill-fated effort to help determine the distance from the Earth to the Sun, Charles Mason, an English astronomer — and Enlightenment avatar, obsessed with categorical imperatives in science and philosophy — set out on a voyage to Sumatra. He is joined in this endeavor by English surveyor Jeremiah Dixon, a free-thinker and boisterous optimist delighted by cultural heterogeneity and outraged by inequities of power and social injustice. Two years later, accompanied by a large party of assistants, the two men embark upon an effort to accurately establish the south boundary line of Pennsylvania (separating it from Maryland and Virginia), as well as the American province’s lower three counties’ boundaries. Pynchon’s recounting of this true story, via an unreliable narrator speaking in an eighteenth-century idiom, is an epic accomplishment. Mason & Dixon are a Zelig-like comedy duo, stumbling upon the secret history of the 19th and 20th centuries, from the Civil War, UFOS, and New Age mysticism to, you know, the history of slavery and cultural domination. America’s vision of liberty and equality is torpedoed, from the beginning, by its Enlightenment-enabled theories of racial and cultural superiority; Mason and Dixon, as they explore and discuss their discoveries on the eve of the Revolutionary War, are emblematic of the fledgling nation’s permanently divided consciousness. Across nearly 80 episodes, they encounter Jesuit cabalists, Native Americans, George Washington and Ben Franklin, a French chef fleeing the amorous attentions of a mechanical duck, a Chinese fêng shui master, a Learned English Dog, and — in one of several examples of meta-textual japery — an ancestor of Pig Bodine, from Pynchon’s 1963 apophenic adventure V.. Depending on who’s listening at any particular moment, the story mutates from heroic tall tale to paranoid quackery to objective description… which is to say, it’s an example of self-aware historicizing. Fun facts: Twenty years in the writing, Mason & Dixon was hailed by readers as the author’s most brilliant and entertaining novel since Gravity’s Rainbow (1973); some critics, including Harold Bloom, have described it as Pynchon’s masterpiece.

- J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter fantasy adventure Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (US title, 1998: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. If asked to recommend a great novel about an adolescent wizard-in-training, I’d suggest the works of Susan Cooper, Ursula K. Le Guin, Diane Duane, and Monica Furlong, not to mention the fantasy novels of E. Nesbit, P.L. Travers, T.H. White, Edward Eager, C.S. Lewis, and Diana Wynne Jones. I don’t find Rowling’s writing as compelling as these earlier authors’… but that said, the first installment in her wildly popular series is enjoyable. On his 11th birthday Harry Potter, an orphan mistreated by his Spiker- and Sponge-like aunt and uncle, receives a letter of acceptance into Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. (His parents, he learns, were killed by a magus so evil and powerful that — even though he is supposedly gone — most wizards and witches fear to speak his name aloud.) Hogwarts is an old-fashioned English boarding school, whose houses — Gryffindor, Slytherin, Hufflepuff and Ravenclaw — compete throughout the year for glory. Harry is befriended by the hapless Ronald Weasley and the brilliant but aggravating Hermione Granger; and he makes an enemy of the snobbish Draco Malfoy. Harry takes classes from colorful instructors, including the sardonic Snape, who seems to hate the new boy at first sight; he joins the Quidditch team; and he is mentored by Dumbledore, the headmaster, and the half-giant Hagrid. But there’s a dark mystery afoot: What is huge three-headed dog guarding in the forbidden corridor? And are rumors about the return of the dark magus true? Fun facts: Rowling’s first novel remained at the top of the New York Times list of best-selling fiction — for children and adults, combined — for much of 1999 and 2000. It was followed by six much-anticipated sequels. The Warner Brothers series of movie adaptations — starring Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, and Emma Watson — is the third-highest grossing series ever, after Star Wars and the Marvel movies.

- Gail Carson Levine’s fantasy adventure Ella Enchanted. In this girl-power retelling of the Cinderella folk tale, the titular Ella is enchanted at birth with the inability to disobey a direct order. As she grows up, the saucy Ella struggles to achieve autonomy; after losing her mother, and being bullied by her loathsome stepmother and stepsisters, she hits the road in search of the fairy whose curse she can no longer bear. The fantasy kingdom of Frell is well-realized, particularly when it comes to language; Levine uses complex words, and Ella herself becomes something of a master linguist when it comes to Elvish, Gnomish, and Ogre languages. The romantic element is also a welcome change; Prince Char is Ella’s friend, first and foremost, and she has no interest in turning to him for rescuing. There’s a ball, a pumpkin coach, and a glass slipper; also a gnome-crafted necklace and a magic book something which functions more or less like the propaedeutic enchiridion in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. At the end of this fractured fairy tale, in a nod to Little Women, Ella must choose between marrying her sweetheart and breaking the enchantment herself — through an exercise of sheer willpower. Fun facts: Winner of the Newbery Honor. The 2004 movie version starring Anne Hathaway and Hugh Dancy was successful, though fans of the book consider it one of the worst adaptations of all time.

- Molly Gloss’s sci-fi adventure The Dazzle of the Day. A slow-moving generation-ship adventure, about an international community of Quakers — Costa Rican, Japanese, and Scandinavian — which abandons the dying Earth and heads towards two possible planets. The story is bracketed by the reminiscences of two older women, the first of whom recalls how the Quakers came to inhabit the ship (only an intentional community can make it work), the second of whom looks back on the initial period of colonizing the group’s new home. In between, we read about the struggles of the voyagers to keep their ship’s machinery and agriculture going, their initial exploration of a not-very-hospitable planet, and their anxieties about whether or not they should actually leave the ship once they arrive. After all, several generations have lived and died within the ship’s embrace; they’re terrified by the prospect of phenomena like weather, wild animals, and a horizon. It’s a Le Guin-like yarn — concerned with thoughtful discussion, the warp and weft of human relations, and the mindful tending of one’s natural environment rather than with explosions, battles, bug-eyed monsters, or high-tech gadgets. It gave me hope for humankind’s future. Fun facts: The title comes from one of Walt Whitman’s poems in Leaves of Grass, a Quaker-ish quatrain about how it is silence that perfects the symphony. “This miraculous fusion of meticulous ‘hard’ science fiction with unsparing realism and keen psychology,” writes Le Guin in her blurb for the book, “created a vast, bleak, beautiful vision of the human figure — a triumph of the imagination.”

- Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson’s cyberpunk comic Transmetropolitan (1997–2002). At some point in the 23rd century, Spider Jerusalem — a Hunter S. Thompson-esque gonzo journalist — returns from his mountaintop refuge to The City, in search of stories to report. Accompanied by sidekicks Yelena Rossini and Channon Yarrow, Spider gets the scoop. For example: The Transients, who’ve modified their genes with alien DNA, and who as a result have been forced to live in a squalid shanty town, are getting ready to secede; their leader, however, turns out to be a police-paid agent provocateur! In the series’ second year, Ellis proves truly prescient when he introduces us to Gary “The Smiler” Callahan, a politician whose base is a far-right hate group… and whom the people vote into office, despite the fact that he’s not merely corrupt but evil. Callahan uses the power of his office to suppress Spider’s journalism — and even goes so far as to arrange for the City to be left defenseless when a Katrina-like “ruinstorm” threatens to kill thousands, in order to destroy Spider’s evidence and as an excuse to declare martial law. When Spider contracts an Alzheimer’s-like disease, will he be able to expose Callahan’s perfidy before he’s completely debilitated? Fun facts: Originally published under DC Comics’s sci-fi Helix imprint, then switched to the Vertigo imprint (under the stewardship of Karen Berger), where it remained one of DC’s most successful nonsuperhero comics.

- Natsuo Kirino’s crime adventure アウト (pub. in English, in 2004, as Out). When Kenji, a suburban office worker, falls in love with a nightclub hostess and squanders his family’s savings on her, his abused and fed-up wife Yayoi strangles him. Seeking to cover up the murder, Yayoi reaches out to Masako, a fellow worker on the night shift at a Tokyo bento-box factory; Masako recruits their shift leader, Yoshie, an older woman who agrees to help out for a price. When the unreliable Kuniko, another night-shift worker, deals herself into the scheme, Masako’s careful plan begins to fall apart. The women aren’t friends, exactly, but what they have in common are unloving husbands, difficult children, and unsatisfying lives and careers in a male-dominated society. Although the amateur criminals dismember and dispose of Kenji’s corpse, police detectives begin to sniff around; so do yakuza. Soon, the four women are drawn into Tokyo’s underworld… and they turn on one another, too. Masako, the best-educated and shrewdest of the group, emerges as a heroine determined to leverage any opportunity to escape her dead-end life. Writing for HILOBROW, Gordon Dahlquist described Out as a “taut and unforgiving thriller that unfolds as darkly as anything from Jim Thompson, if Jim Thompson was a cold-eyed feminist.” Fun facts: Winner of the Mystery Writers of Japan Award for Best Novel. A 2002 Japanese film adaptation, directed by Hirayama Hideyuki, was a flop. However, Nakata Hideo (Ring, Ring 2) is reportedly developing an American adaptation.

- Lee Child’s Jack Reacher crime adventure The Killing Floor. When Jack Reacher steps off a bus in the town of Margrave, Georgia — he’s spent his entire adult life in the military, where he’s gained expertise in commando tactics and routine law enforcement procedures; now, he’s an aimless drifter, just seeing the sights — he’s arrested for murder. Think In the Heat of the Night, if Virgil Tibbs was an Eighties action hero-esque white man. One also catches a strong whiff of Peter Cheyney’s Lemmy Caution — a bad-ass avenger who shows up, miraculously, when the authorities are too corrupt or incompetent to serve justice upon the wicked. (Like Cheyney, Child is a British writer expertly faking an American pulp idiom.) The town’s sherriff, Morrison, claims he saw Reacher leave the scene of the crime; but Roscoe, a female detective, believes him to be innocent. The action is fast and furious: Reacher battles an Aryan Brotherhood murder attempt; he ambushes members of a counterfeiting ring; he battles a corrupt FBI agent; he hooks up with Roscoe. There are explosions. Neither well-written nor original, but nevertheless thrilling, Child’s first Reacher story would serve as a template for a best-selling franchise. Fun facts: There are 24 Jack Reacher novels, thus far; three of them — The Enemy (2004), Night School (2016), and The Affair (2011) — are prequels to The Killing Floor. The 2012 Christopher McQuarrie adaptation of Child’s One Shot (2005), starring Tom Cruise, is a guilty pleasure for me.

- John Wagner and Vince Locke’s graphic-novel thriller A History of Violence. When two thugs attempt to rob his cafe — in a small Michigan town — Tom McKenna stops them with surprising facility. The story goes national, and soon three New York mafiosi show up. One of them, John Torrino, an aging hitman, insists that McKenna is a former mobster names Joey — who’d taken it on the lam 20 years earlier. Tom’s wife, Edie, and the local sheriff attempt to drive the men off — but when they take Buzz, Tom and Edie’s son, hostage, the truth is revealed. Mild-mannered Tom has a history of violence! In fact, in order to acquire the money that his grandmother needed for heart surgery, he and a friend had killed a New York crime boss, along with several associates, and stolen a large sum of money. He’s lived under an assumed identity ever since. Even once Tom and Edie rescue Buzz, the story isn’t over. It seems that Tom’s old friend has been a prisoner of the dead mobster’s sadistic son, for all these years. Can he rescue him? And if he returns to a life of violence, will he lose his family? Vince Locke, whose ultra-violent watercolors have been used as album covers by a death metal band, provides cinematic, gruesome, yet sketchy and cross-hatched — storyboard-like — artwork. Fun facts: Originally published in 1997 by Paradox Press and later by Vertigo Comics, both imprints of DC Comics. Wagner, though born in the US, grew up in England. In 1977, with artist Carlos Ezquerra, he developed the character Judge Dredd for 2000 AD. (Warren Ellis, Alan Moore, and others were inspired by Wagner’s work.) David Cronenberg’s excellent adaptation of A History of Violence, starring Viggo Mortensen, Maria Bello, Ed Harris, and William Hurt, appeared in 2005.

- Jonathan Lethem‘s sci-fi adventure As She Climbed Across the Table. Philip, an anthropologist at a northern California university, finds himself growing jealous of a wormhole created in a particle collider. His girlfriend, particle physicist Alice Coombs, seems to have developed a personal, emotional relationship with Lack — which is what she and her colleagues have named the enigmatic portal leading to a new, uninhabited universe. Why has the wormhole remained open, and why will it only accept particular objects — Alice’s keys, or a pomegranate, or the campus cat, say, but not a paperclip — offered to it? If his earlier novels were mashups of sci-fi with westerns and film noir, Lethem — like Alice, an experimentalist — here tries his hand at the campus novel, not to mention the rom-com. It’s guaranteed to entertain fans of postmodern campus novels like Barth’s The End of the Road and DeLillo’s White Noise. A visiting Italian physicist, Braxia, proposes a shocking hypothesis… which Philip, our narrator, whose own study of “departmental politics and territorial squabbles, the places where disciplines overlapped, fed back and interfered” makes him an ideal observer, decides to test. Offering himself up as a kind of human sacrifice to Lack, Philip wakes up in an alternate version of his (our) own universe. What has he proven, exactly? And how will he return? Fun facts: Is it possible to create a universe in the laboratory by quantum tunneling? In the early 1990s, physicists Edward Farhi and Alan Guth explored the possibility that quantum effects might permit a new universe — created by producing “a small bubble of false vacuum” — to tunnel into a larger bubble, of the same mass, which would then evolve to become a new universe.

- Connie Willis’s Time Travel sci-fi adventure To Say Nothing of the Dog. Willis’s first Oxford Time Travel adventure, the Hugo- and Nebula-awarded Doomsday Book (1992), was a kind of voyage into the Domesday Book of 1086. The sequel takes temporal historian Ned Henry, employee of Oxford’s Temporal Physics department (c. 2057), to 1888 — into the world of Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), Jerome K. Jerome’s 1889 whimsical, semi-autobiographical account of a two-week boating holiday along the Thames from Kingston upon Thames to Oxford and back again. Ned will take his own ill-fated voyage on the Thames, in the company of two companions and a dog; along the way, they will encounter the Three Men in a Boat characters. This charming mise en scène is the setting for a mystery: What time traveler has violated “the laws of the continuum” by bringing an object back from 1888 to 2057? (Such violations can cause time itself to unravel.) And what does this have to do with Ned’s primary assignment: to ascertain what became of “the bishop’s bird stump” when Coventry Cathedral was bombed by the Germans during World War II? Our protagonist’s unfamiliarity with the 19th century, as well as the “time lag” from which he suffers, make things even more complicated than they otherwise might have been. Ned’s colleague, Verity Kindle, attempts to help him fix the time travel incongruity…. Too late? Fun facts: To Say Nothing of the Dog was followed by the two-part Time Travel series installment Blackout/All Clear (2010). All four of her Time Travel books were awarded a Hugo; Blackout/All Clear was also awarded a Nebula. In fact, Willis has won more major science fiction awards than any other writer.

- Daniel Clowes‘s apophenic graphic novel David Boring (serialized 1998–2000). As some sort of international conflict involving germ warfare looms menacingly, David Boring roams an unnamed city in search of the perfect woman. He falls in love with Wanda, whom he (mistakenly) believes is the very one he’s been seeking; however, she breaks up with him — and then a mysterious stranger shows up and shoots David in the head. He survives, with a small dent in his forehead, and ends up retreating with his mother, his roommate and friend Dot, and various others to a Boring family compound on the island Hulligan’s Wharf; terrorist gas attacks have contaminated the mainland, they are informed. Romantic hijinks ensue, with the result that Dot ends up running away with David’s cousin Iris, and his mother runs away with Iris’s husband — who may or may not have killed Iris’s mother. Back in the city, David encounters the man who shot him, as well as Wanda’s sister, Judy, a married woman whom he now believes to be the woman he truly needs. A federal agent shows up, who — obsessed with Iris — determines to frame Dot and David for murder. After other misadventures, the friends make their way back to Hulligan’s Wharf, where they hope to survive what may or may not be the end of civilization as we know it. One of my favorite aspects of the story is how David broods over specific panels in Golden Age comics written and drawn by his missing father; I find this extremely evocative. Fun facts: Asked to describe David Boring in a one-sentence sales pitch, Daniel Clowes said, “It’s like Fassbinder meets half-baked Nabokov on Gilligan’s Island.” The graphic novel was serialized in issues #19–21 of Clowes’s comic book Eightball, and appeared in collected form in 2000.

- Iain M. Banks’s Culture sci-fi adventure Inversions. Banks’s Culture — an interstellar, highly advanced and enlightened civilization whose Contact group observes less-civilized societies without intervening, but whose Special Circumstances agents sometimes scheme to speed up their social evolution — is here portrayed from the perspective of members of two such societies. Inversions can be read as a medieval-ish fantasy; those familiar with Banks’s other sci-fi books may suspect that two of its characters hail from the Culture. One of our two storylines concerns DeWar, bodyguard to General UrLeyn — who is leader of Tassasen, a Calormen-like realm on the other side of the planet. When DeWar isn’t protecting UrLeyn and his family from assassination attempts, he’s playing board games with Perrund, trusted advisor to UrLeyn (and former concubine) whose troubled past we slowly discover. DeWar’s stories of a magical land where “every man was a king, every woman a queen,” and where people enjoy a carefree and easy life in pursuit of knowledge and enlightenment, sound quite a bit like… the Culture. Our other storyline is narrated by the assistant to Vosill, a mysteriously capable, highly unconventional female doctor. Resentment towards Vosill, who supposedly hails from a country far from Haspidus, the Narnia-like kingdom where the story is set, builds as she nudges Quience towards permitting commoners to own farmland without the oversight of a noble, among other reforms. The “Doctor” storyline is something of a murder mystery, as various members of the court are offed mysteriously. Whodunnit? Fun facts: The initial hardback printing of the book contained a “Note on the Text” suggesting that Vosill hailed “from a different Culture.” The book’s epilogue notes that Vosill disappeared from a ship on which she was traveling, after declining an invitation to dine with its captain — citing “an indisposition due to special circumstances.”

- Joann Sfar and Lewis Trondheim, et al.’s Donjon comic-book series (Dungeon, 1998–ongoing). Herbert the Duck, Marvin the Dragon, Hyacinthe de Cavallere (the Dungeon Master), and the rabbit Marvin the Red are the central characters of the ambitious Donjon series, which now runs to some 30 volumes. The funny yet sometimes grim Dungeons & Dragons-esque saga, which spans various epochs (Early Years, Zenith, Twilight) and and spinoff series (Parade, Monstres, Antipodes), is set in and around a lethal Escape-the-Room-esque dungeon set up as a business… i.e., in order to attract adventurers who’d be killed, allowing the Dungeon Master to profit from their possessions. The humanoid duck Herbert possesses a magical sword — a parody of Elric of Melniboné’s Stormbringer, perhaps — that’s almost as troublesome to its possessor as it is to his foes. The Dungeon Master’s henchman, Marvin the Dragon, is a fierce warrior-monk and Herbert’s reluctant protector on many a quest and misdventure. French comics artists Joann Sfar and Lewis Trondheim dreamed up this scheme, and produced many of the Twilight and Zenith installments they’ve invited other talented friends — including Christophe Blain, Boulet, and Manu Larcenet — to participate, too. Endlessly inventive and surprising, an amazing accomplishment. Fun facts: “Dungeon comics — that’s a big inspiration for me and the crew who write on [Adventure Time],” Pendleton Ward has said. “Dungeon’s a great comic, and I look to it for the sort of casual conversation they have with the big fantasy world that they all live in.” Here’s a helpful guide to the series by Jeff VanderMeer.

- Dennis Lehane’s Kenzie and Gennaro crime adventure Gone, Baby, Gone. In their fourth outing, a fan favorite, Boston private eyes Patrick Kenzie and Angie Gennaro are hired to investigate the disappearance of a 4-year-old girl, Amanda — whose mother, they discover, is a barfly, TV addict, and negligent parent. Teaming up with Crimes Against Children (CAC) officers Remy Broussard and Nick Poole, Kenzie and Gennaro plunge into Boston’s underworld — following a trail that leads to their old classmate, Cheese, a drug dealer from whom Amanda, they learn, has stolen a large amount of money. The duo is aided, as in other stories, by a fellow Dorchester hoodrat, sociopathic gunrunner Bubba Rogowski. This is something of a morality play: Our heroes are forced to argue, with each other and within their own hearts, about what’s best for a child — to be raised in a stable environment, or by their own blood. A ransom demand leads the four investigators to the Quincy Quarries, where under cover of darkness a confused gun battle breaks out, leaving two gangsters dead, the ransom money missing, and a clue that suggests that Amanda may be dead. There’s a plot twist in which we discover that the good guys aren’t all good, nor the bad guys all bad. Things end inconclusively…. Fun facts: Preceded by A Drink Before the War (1994), Darkness, Take My Hand (1996), and Sacred (1997); followed by Prayers for Rain (1999) and Moonlight Mile (2010). The 2017 adaptation directed by Ben Affleck stars Casey Affleck and Michelle Monaghan.