This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Sixties (1964–1973, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). Although it remains a work in progress, and is subject to change, this BEST ADVENTURES OF THE SIXTIES list complements and supersedes the preliminary “Best Sixties Adventure” list that I first published, here at HILOBROW, in 2013. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

PS: Some of the titles on this list also appear on my list of the 100 best YA and YYA adventures of the Sixties.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

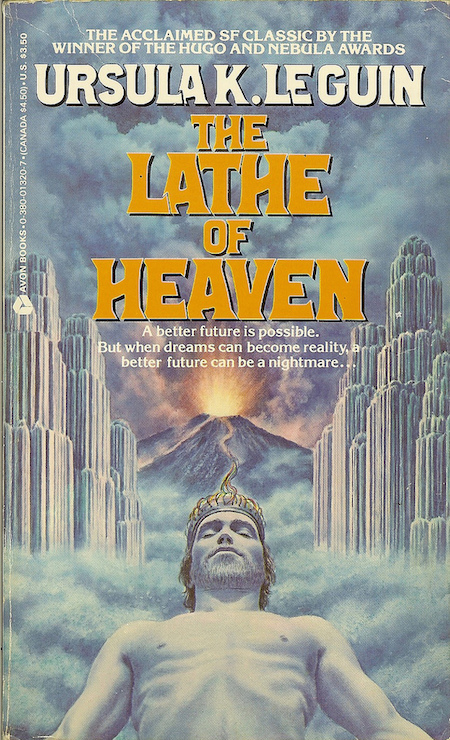

The New Wave era in Adventure’s science fiction sub-genre began in 1964 (when Michael Moorcock took over the editorship of the British sf magazine New Worlds; Jack Kirby also had something to do with it, in science-fiction comics) and lasted through 1983. (Cyberpunk begins in ’84, with Gibson’s Neuromancer.) What was New Wave? The best sf adventures published during the Sixties were characterized by an ambitious, self-consciously artistic sensibility. Many of my favorites — including Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Martian Time-Slip, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and Ubik; William S. Burroughs’s Nova Express; Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven; Samuel R. Delany’s Nova; Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five; and Michael Moorcock’s The Final Programme — concern themselves, at the level of both content and form, with the nature of perception itself.

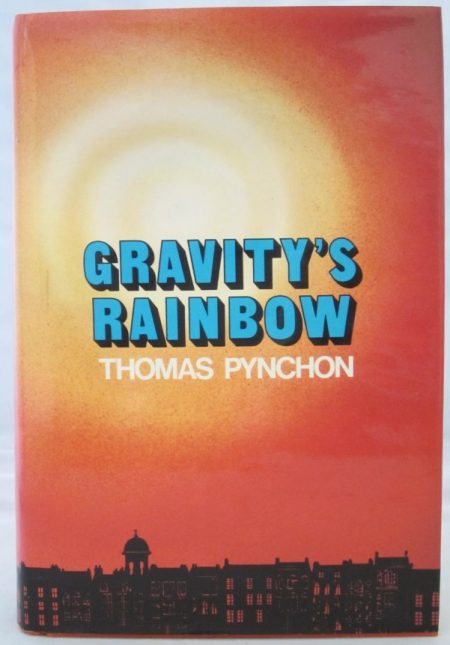

Certain far-out examples of non-sf adventure lit from the Sixties were self-consciously artistic, and concerned — at the level of both content and form — with the nature of perception itself. Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 and Gravity’s Rainbow are the examples that will immediately spring to mind for most people. Other self-reflexive, postmodernist, sardonic inversions of the adventure genre from 1964–1973 include: Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man, Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, Ishmael Reed’s Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down and Mumbo Jumbo, Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, William Goldman’s The Princess Bride, and J.G. Ballard’s Crash. If the avant-garde stories I’ve just mentioned aren’t for you, not to worry: paperback racks in the Sixties were replete with straightforward adventures by the likes of Alistair MacLean, Francis Clifford, Desmond Cory, Duncan Kyle, Andrew Garve, Gavin Lyall, and Desmond Bagley.

As WWII receded from the present, and as the era of anti-Communist paranoia and hysteria ended, the context for straightforward adventure novels became… let’s call it a quagmire. Vietnam didn’t lend itself directly to heroic adventure writing; instead, it inspired the rise of the anti-hero. The protagonists of Charles Portis’s True Grit, George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman adventures, Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal, Trevanian’s The Eiger Sanction, perhaps even James Dickey’s Deliverance — they’re not fighting in Vietnam, but that’s their context. PS: There was a Sixties war whose advent and outcome served as a backdrop to three excellent adventure novels of the period. The 1967 Arab-Israeli War (also known as the Six-Day War) is the lens through which Lionel Davidson’s A Long Way to Shiloh, Making Good Again, and Smith’s Gazelle ought to be viewed.

Adventure TV shows and movies from 1964–1973 often put a sardonic twist on the adventure genre: Hogan’s Heroes plays the prison-break/WWII adventure trope for laughs; Gilligan’s Island does the same for the Robinsonade. (The Prisoner was self-consciously artistic, and concerned — at the level of content and form — with the nature of perception itself.) Movies, too: Michael Caine’s Len Deighton spy movies, James Coburn in Our Man Flint, even the Beatles’ Help! were sardonic inversions of Adventure’s espionage sub-genre. Sergio Leone’s movies with Clint Eastwood are revisionist Westerns. Many other movies from the era — The Dirty Dozen, The Wild Bunch, Tom Laughlin’s Billy Jack — are Vietnam-inflected actioners.

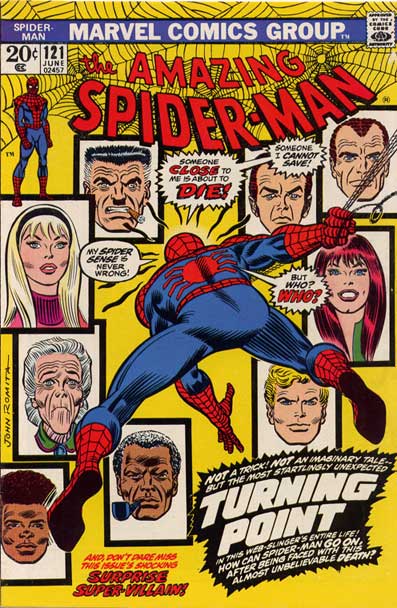

One final note. If the Golden Age for children’s and YA adventures began in the Fifties (see the previous post in this series), then that Golden Age reached its apex from 1964–1973. Susan Cooper’s Dark is Rising series, Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy, Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese comic strip, Richard Adams’s Watership Down, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series, Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Joan Aiken’s Wolves Chronicles series, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wind in the Door, Jean Merrill’s The Pushcart War, John Christopher’s Tripods trilogy and Sword of the Spirits trilogy, S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, E.L. Konigsburg’s From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, Peter Dickinson’s Changes trilogy, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, Ian Fleming’s Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain series, Alan Garner’s Elidor and The Owl Service, not to mention Jack Kirby’s various “Fourth World” DC comics series and Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth… it doesn’t get any better than this.

- Thomas Berger’s revisionist Western adventure Little Big Man. Jack Crabb, a 111-year-old survivor of Custer’s Last Stand, narrates his mock-heroic, picaresque adventures. As his roles vary over the course of his wanderings, from Cheyenne warrior to Army scout to small-time huckster, so does the style of Crabb’s (unreliable) narrative. Adapted as a movie in 1970 by Arthur Penn.

- Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure Martian Time-Slip. In which the Mars of hoary sf mythologizing becomes a Waste Land populated by visionary bushmen, a truth-telling ten-year-old schizophrenic (who sees “a hole as large as a world; the earth disappeared and became black, empty, and nothing… Into the hole the men jumped one by one, until none of them were left. He was alone, with the silent world-hole.”), and a humble repairman who must put reality back together… even as it dissolves into “gubble.”

- Jim Thompson’s crime adventure Pop. 1280. Nick Corey, who is sheriff of some Texan (probably) backwater, would have his neighbors (and us) believe that he is a lazy, simple-minded good ol’ boy who nevertheless manages to deal effectively with a shrewish wife, a tough re-election campaign, and local criminals. In fact, he is a cunning and ruthless sociopath.

- Louise Fitzhugh’s YA espionage adventure Harriet the Spy. Perhaps my favorite YA novel ever. Harriet is an amazing character. She’s praiseworthy in her intrepid, self-motivated, eccentric (and un-supervised) adventuring; a talented crafter of gnomic aperçus; a loyal friend and a terrifying enemy. And yet, she’s in the wrong; the reader knows it, and so does everybody else in the book. It’s an emotional roller-coaster ride.

- Len Deighton’s 1964 satirical spy novel Funeral in Berlin. Deighton’s unnamed protagonist travels to Berlin to arrange the defection of a Soviet scientist… and stumbles upon a complicated game of maneuvers between the Israeli secret service, ex-Nazis, and Russian security. Guy Hamilton’s 1966 movie adaptation starred Michael Caine.

- J.G. Ballard’s science fiction adventure The Burning World. Part of an early-career series of eco-catastrophe novels by the author, who until 1962 worked as an editor at the British scientific journal Chemistry and Industry. An extreme worldwide drought is caused by industrial waste flushed into the ocean; an oxygen-permeable barrier of saturated long-chain polymers has formed, which prevents evaporation and destroys the precipitation cycle. A longer version was published in 1965 as The Drought.

- William Burroughs’s cut-up science fiction adventure Nova Express. Inspector Lee tracks down members of the Nova Mob — regulating viruses, known as Sammy the Butcher, Izzy the Push, and The Subliminal Kid, who represent society, culture, and government. Third and best installment in the Nova trilogy, which begins with The Soft Machine (1961, revised 1966) and The Ticket That Exploded (1962, revised 1967). Luc Sante sums up the message of the trilogy like so: “You are the host of a virus; the virus is life; you are fucked.”

- Donald E. Westlake’s Parker crime caper adventure The Score, written under the pseudonym Richard Stark. Recruited by a mysterious figure, Parker recruits a group of twelve experts in order to run a heist on an entire town in North Dakota. Slow-moving, compared to earlier Parker books — there’s a lot of planning and waiting — but when the job goes wrong, things start jumping. Fifth in the Parker series; published in the UK as Killtown. Darwyn Cooke’s graphic novel adaptation is worth a read.

- John Christopher’s Sweeney’s Island is a sardonic inversion of the Robinsonade genre of adventure. I’m a big fan of Christopher’s YA trilogies from this era, which is why I picked up this book — which turns out to be a grownup version of Lord of the Flies. A group of wealthy London socialites are invited on a sailing trip which strands them on an uninhabited tropical island; things get post-apocalyptic. Lost avant la lettre.

- John D. MacDonald’s crime adventure The Deep Blue Good-by. The first in a long, much-beloved series of pulp novels about “salvage consultant” Travis McGee, a Korean War vet who lives on a houseboat in Fort Lauderdale and recovers stolen property and missing persons — forebear to Elmore Leonard and Carl Hiaasen’s Florida adventurers. Here, McGee races to discover buried treasure before a murderer gets there first.

Note that 1965 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Sixties. The transition away from the previous era (the Fifties) begins to gain steam….

The years 1963 and 1964 were cusp years between the eras we think of as the Nineteen-Fifties and Sixties; by ’65 the Sixties were fully underway, building steam as the era headed towards its 1968–69 apex. In the best adventure novels of 1965, we find few relics of the Fifties: things are falling apart; the center isn’t holding.

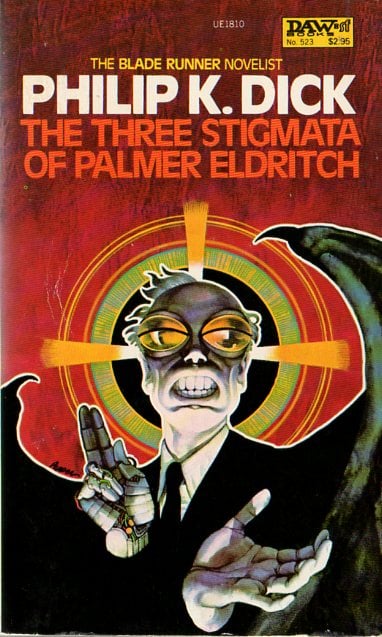

- Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. Via an odyssey of nested hallucinations, Dick burns the Gnostic idea that the world is the creation not of God, but of an evil, lesser deity, forever into the reader’s mind. The title character is a demiurge who brings to mankind a “negative trinity” of “alienation, blurred reality, and despair.” Probably my favorite PKD novel, after A Scanner Darkly.

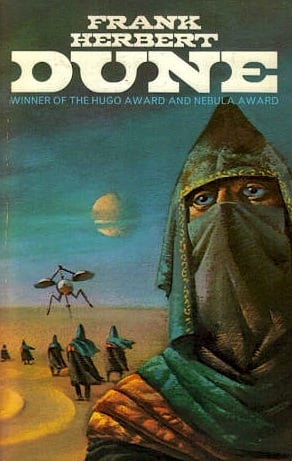

- Frank Herbert’s science fiction adventure Dune. A potboiler about one family’s declining empire, a mythology-saturated fantasy about the founding of a new social order, and a band-of-brothers yarn (Thufir Hawat, the human computer; Gurney Halleck, the troubadour warrior; Duncan Idaho, master swordsman), Dune is also a criticism of humankind’s despoliation of nature in the name of progress. Plus: Alia, a telepathic four-year-old girl, who roams the battlefields of Arrakis slitting the throats of imperial stormtroopers! The Bene Gesserit, who subtly guide humanity’s development! The worm-riding Fremen! Dune was adapted into David Lynch’s cult 1984 movie of that title.

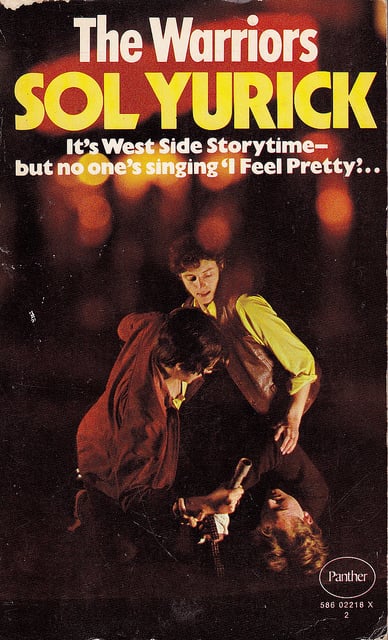

- Sol Yurick’s hunted-man adventure The Warriors. After an assembly of New York gangs devolves into chaos, the Coney Island Dominators, a black/Hispanic gang of murderers and rapists, must trek home from the Bronx — all the while defending their thuggish sense of manhood — through gang turfs. It’s loosely based on Xenophon’s Anabasis (c. 370 BC), which recounts the travails of Greek mercenaries betrayed and stranded deep within enemy territory. The Warriors was adapted into a cult 1979 movie of that title.

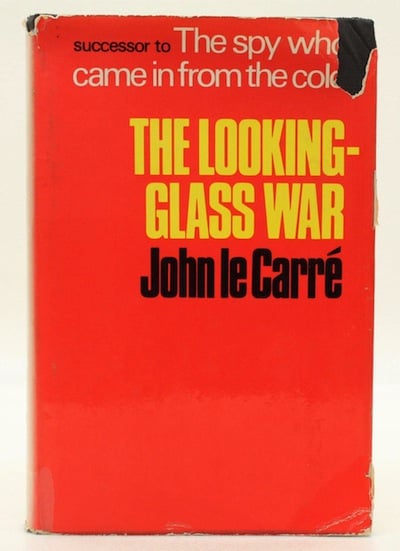

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure The Looking Glass War A nearly defunct WWII-era British Intelligence agency (“The Department”) suspects that Soviet missiles are being placed near the West German border, and although they have no evidence that this is the case (shades of George W. Bush’s 2003 Iraq invasion), because they long to get back into the game they recruit one of their former wartime agents to infiltrate East Germany. A tragicomedy of errors ensues, and the unlucky agent is in the end abandoned to the mercies of the other side. The Looking Glass War was adapted into a 1969 movie starring Christopher Jones.

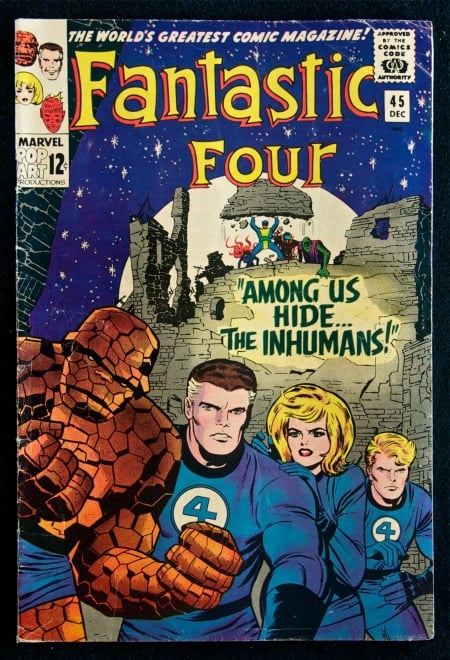

- Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s November 1965 – March 1966 issues of Fantastic Four, featuring The Inhumans. Prior to the Sixties (1964–1973), Lee and Kirby created superhero teams who’d develop into beloved, enduring franchises: The Fantastic Four in ’61, The X-Men in ’63, The Avengers in ’63. But the Inhumans were a different kettle of fish: misfits and outsiders even among mutant superheroes, a superior race living in the shadows. Black Bolt, Crystal, Karnak, Medusa, Gorgon aren’t lovable; in fact, they’re slightly villainous. But that just makes them an all the more romantic version of the Argonaut Folly mytheme.

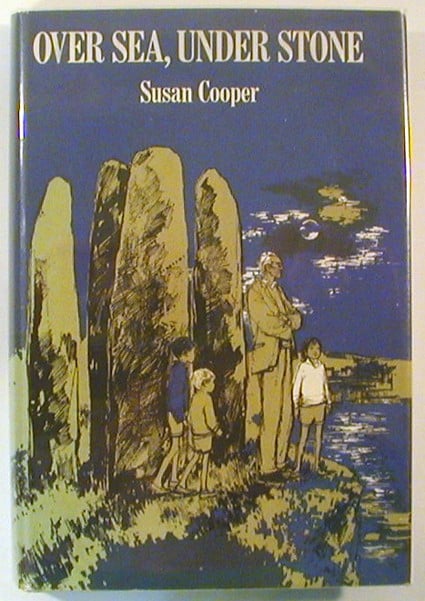

- Susan Cooper’s YA fantasy adventure Over Sea, Under Stone. This is the first installment in The Dark is Rising: the best YA fantasy series ever, not to mention one of the best “Matter of Britain” (i.e., medieval Arthurian legend) adventure series. This particular installment is not particularly fantastical: It’s a treasure-hunt thriller featuring three siblings on holiday in Cornwall. However, although the story begins in this Famous Five/Swallows and Amazons vein, soon enough we discover that the treasure the children (and some creepy adults) are seeking is in fact an artifact of the Light: a faction, that is to say, in an ancient, ongoing, worldwide struggle of free will and order vs. subservience and chaos!

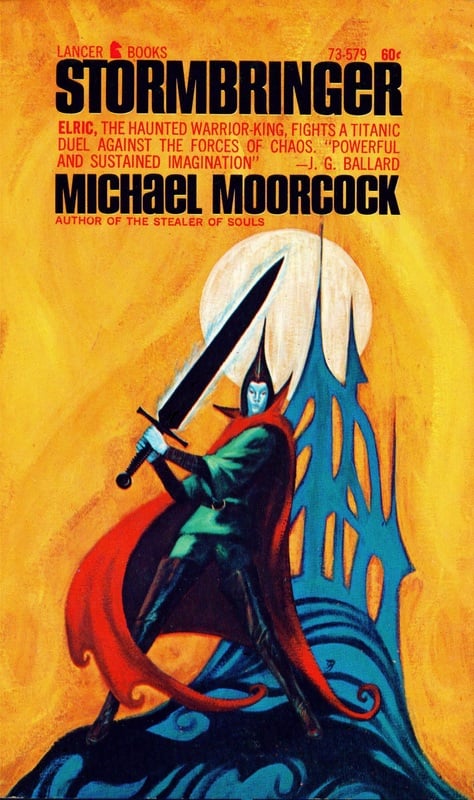

- Michael Moorcock’s fantasy adventure Stormbringer. Even though Stormbringer, which takes its title from the name of Elric’s cursed sword (which confers upon the user health and fighting prowess, but must be fed souls in return), is a “fix up” combining four novellas from the early 1960s, it was ahead of its time even when reissued as part of DAW’s canonical 1970s Elric series. Moorcock’s albino, drug-addicted protagonist Elric of Melniboné was influenced by Bertolt Brecht’s amoral, antiheroic criminal character Macheath; even when Elric tries to do the right thing, he ends up destroying those about whom he cares most.

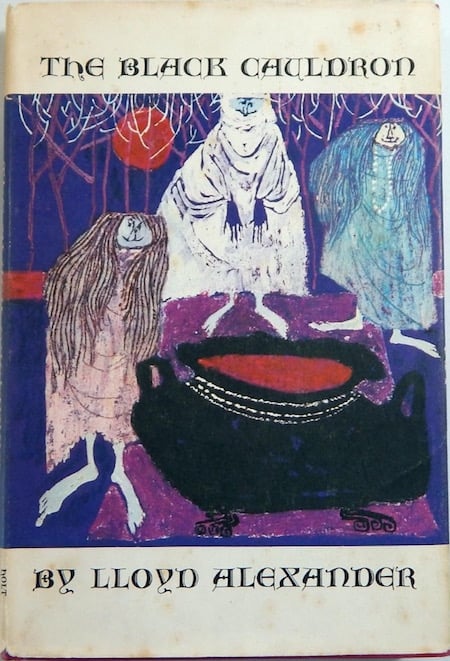

- Lloyd Alexander’s YA fantasy adventure The Black Cauldron. The second in a series of Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain books, which use Welsh mythology (Prydain is the medieval Welsh term for the Brittonic parts of the island of Britain), particularly the Mabinogion, for inspiration, The Black Cauldron is my favorite. The antiheroic Prince Ellidyr, who loves only his horse, sickly Gwystyl of the Fair Folk, the sorceresses Orddu, Orwen, and Orgoch, and the doomed minstrel Adaon are tremendous characters. It’s like Moorcock’s Elric series without the sex, drugs, and despair.

- Agatha Christie’s hunted-man thriller At Bertram’s Hotel. Or perhaps it’s a crime adventure? The fact that it’s impossible to say which is precisely what’s so rewarding about Christie’s tenth, often overlooked Miss Marple yarn. The elderly amateur sleuth takes a holiday at a London hotel whose guests include a famous adventuress, a forgetful clergyman, and a wealthy young heiress traveling with her guardian. An Irish Mail train is robbed, the clergyman is abducted (or is he?), shots are fired, a body is discovered: What happened? In the end, it turns out, the story’s mise en scène is all that matters.

- Adam Hall’s espionage adventure The Berlin Memorandum. This is the first of nearly 20 Quiller novels, which have been disparagingly described as “a hybrid of glamour and dirt, Fleming and Le Carré” — which, to this reader, is no disparagement at all. Like Fleming’s Bond character, Quiller is a skilled driver, pilot, and diver; however, he doesn’t carry a gun. His mission, like that of Alec Leamas in Le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, is to be captured by the enemy, be tortured, then reveal false information! The book was adapted in 1966 as The Quiller Memorandum, starring George Segal and Alec Guinness.

- Thomas Pynchon’s postmodernist, apophenic adventure The Crying of Lot 49. Has discontented California housewife Oedipa Maas uncovered a centuries-old conflict between two mail distribution companies? Or is she perhaps merely detecting signals where there is only noise? “The ordered swirl of houses and streets, from this high angle, sprang at her now with the same unexpected, astonishing clarity as the circuit card had. Though she knew even less about radios than about Southern Californians, there were to both outward patterns a hieroglyphic sense of concealed meaning, of an intent to communicate.” Fun fact: Pynchon’s fictional aerospace engineering company, Yoyodyne, is referenced in the movie The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai.

- Richard Fariña’s comical picaresque Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me. Gnossos Pappadoupoulis, an undergrad at a thinly fictionalized version of Cornell University, is — like Odysseus — a world-weary traveler who has returned home a changed man. Having spent time in Cuba during the revolution, Pappadoupoulis returns to “Athene” to become the inadvertent leader of a student rebellion against a university edict banning women from men’s apartments. An admirer of the comic book superhero Plastic Man, Pappadoupoulis prides himself on being adaptable, a hustler, a trickster — yet he yearns to find meaning in a plasticized society. Fun fact: The author was a folksinger who died, in an accident, two days after this first novel was published. Thomas Pynchon would dedicate Gravity’s Rainbow to Fariña.

- Samuel R. Delany’s New Wave science-fiction adventure Babel-17. Starship captain, codebreaker and telepath Rydra Wong discovers that a software code used by an enemy civilization’s hackers is actually a language… one which alters perception and thought, enhancing your abilities but turning you into a traitor! Babel-17 is an adventure yarn — including everything from hand-to-hand combat to full-scale spaceship battles — but at the same time it’s a philosophical novel challenging the reader to imagine what kind of culture might speak a language lacking a pronoun, or any other construction for “I.” Fun fact: Babel-17 was joint winner of the Nebula Award in 1966 (with Flowers for Algernon) and was also nominated for the Hugo Award in 1967.

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave science-fiction adventure The Unteleported Man. War between the US and the Soviet Union has led to UN rule of the planet, renamed Terra. Theodoric Ferry, a capitalist mogul, is teleporting millions to Whale’s Mouth, the universe’s only other inhabitable planet, a Garden of Eden where Terrans can start over. Freya Holm, an agent with the private police agency Listening Instructional Educational Services (LIES), Inc., speculates that Ferry may be an alien… and that Whale’s Mouth may not be all that it seems. Rachmael Ben Applebaum, owner of an outer-space freighter company that has been disintermediated by teleportation technology, decides to travel to Whale’s Mouth the old-fashioned way… i.e., he will be the only unteleported man. The UN, meanwhile, attempts to defeat Ferry via a mind-control device of their own: a pulp sci-fi novel! Fun fact: Originally published as a novella, in 1964, by the sf magazine Fantastic.

- Lionel Davidson’s hunted-man/treasure-hunt adventure A Long Way to Shiloh (aka The Menorah Men). When Caspar Laing, an Indiana Jones-like British professor of Semitic Languages, is asked to translate an ancient scroll that may give directions to the hiding place of a menorah rescued when Nero’s army in Israel sacked the Temple in 70 AD — that is to say, a sacred relic which is the very symbol of Judaism — he quickly gets tangled up in Middle Eastern politics. The Jordanians, it seems, are also hunting for the menorah… and what’s worse, the scroll is purposely misleading. Veers from deadly cat-and-mouse chills to hermeneutic thrills. Also, it’s funny! One of my all-time favorite adventures.

- J.G. Ballard’s New Wave science-fiction adventure The Crystal World. In the Cameroon Republic, a British doctor discovers that entrance to the forest is being discouraged… but he can’t figure out why. Seeking his friends, who run a leper colony, he travels upriver and discovers a forest of glass. Trees, grass, water, animals and men are slowly encased in glittering crystals. The universe, its myriad of possibilities, is crystallizing into sameness. Fun fact: Serialized in the first Moorcock-edited issue of New Worlds.

- Helen MacInnes’s espionage adventure The Double Image. A minor thriller from one of the great midcentury adventure writers. John Craig, an American historian, is vacationing in Paris when he bumps into Mr. Sussman, an old professor of his and an Auschwitz survivor… who claims he’s just seen an SS Colonel, who’d been reported dead, posing as a Russian. When Sussman is killed, Craig becomes a suspect… at which point he joins forces with French, Italian, British, and American intelligence operatives who are investigating whether the Communist states of Eastern Europe are harboring former Nazis. The action moves to the Greek island of Mykonos, where the Cold War turns smoking hot.

- Francis Clifford’s hunted-man adventure The Naked Runner. A recently widowed Englishman, Sam Laker, comes to the attention of an intelligence operative, Slattery, with who he’d served in the war. When Laker travels to Germany’s Russian Zone on business, taking his teenage son along for a holiday, Slattery asks him to deliver a package. Laker’s son is abducted, and Laker — who, as it turns out, was a merciless guerrilla behind enemy lines, during the war, and who suffers from what we’d now call PTSD — must turn back into an assassin. Fun fact: Frank Sinatra starred in the book’s 1967 movie adaptation. Those Liam Neeson movies seem awfully familiar, when you read this plot description, don’t they?

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave science-fiction adventure Now Wait for Last Year. In the near future, Terra — a unified Earth, the supreme elected leader of which is UN Secretary General Gino Molinari — has become entangled in an unwinnable war between an insect race (the Reegs) and a humanoid race (the ’Starmen) who may be out to exploit Terra’s natural resources. Dr. Eric Sweetscent, a surgeon who specializes in replacing worn-out bodily organs with artificial ones, is secretly asked to tend to Molanari, who has developed a psychosomatic ailment in which he suffers along with anyone near who him who is in any kind of pain. Sweetscent’s wife, meanwhile, takes a drug which — it turns out — causes the subject to move forwards, backwards, and sideways through time. She brings Sweetscent along with her…

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s science fantasy adventure Rocannon’s World.. When ethnologist Gaveral Rocannon visits the primitive planet Fomalhaut II, his ship is destroyed by agents of Faraday, an upstart planet threatening the peaceful galaxy. Rocannon sets out to find the enemy’s secret base on Fomalhaut II. As he journeys across the planet, he encounters various fantasy-esque species, including the dwarfish Gdemiar, the elven Fiia, and the nightmarish Winged Ones; his advanced science makes him a Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court-type wizard. However, when he reaches the enemy base he must revert to a sophisticated interstellar op. Fun fact: Sci-fi fans will be familiar with the concept of an “ansible” — i.e., a faster-than-light communicator. Le Guin first introduced the term here.

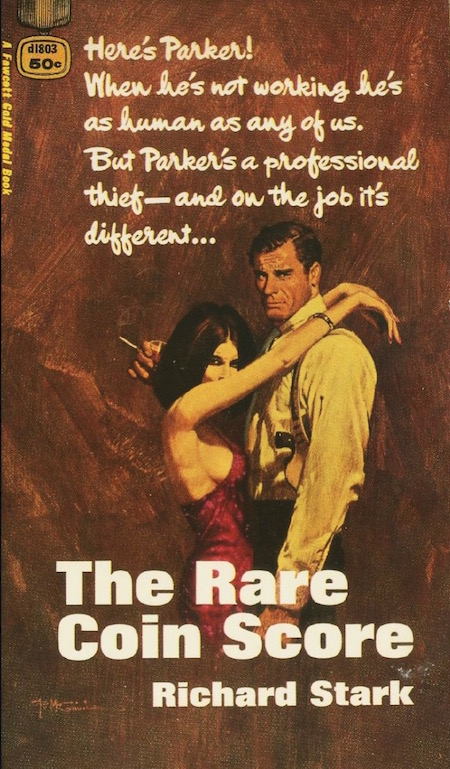

- Richard Stark’s Parker crime adventure The Rare Coin Score. Invited to plan and helm the robbery of a couple of million dollars’ worth of booty from a coin collector’s convention in Indianapolis, master thief Parker — in his ninth outing — finds himself once again hampered by a sub-par heist crew. (“Billy wanted to fall apart under pressure, he wanted it the way a torture victim wants to die. Lempke himself felt the weakness of age and worry lapping at the edges of his mind. Otto Mainzer, a crazy man, a destroyer, was being held in check by the authority of Parker.”) Why doesn’t he bail? Because he falls in love — a first, for Parker — with Claire, a beautiful and smart woman in on the caper. When things go wrong, as they inevitably will, Parker must scramble to save himself, the loot, and the girl. Fun fact: In his terrific introduction to a recent reprint of The Rare Coin Score, HILOBROW friend Luc Sante writes: “Stark portrays a world of total amorality. It is never suggested in the novels that robbing payrolls or shooting people who present liabilities are anything more than business practices.”

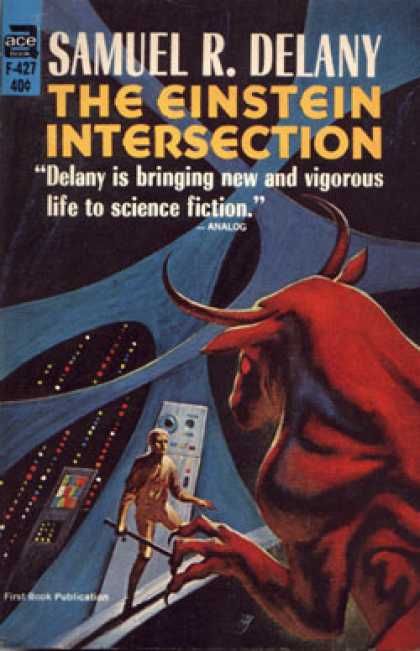

- Samuel R. Delany’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Einstein Intersection. Love it or hate it (Delany’s eighth novel has zealous fans and detractors), The Einstein Intersection is fascinating. Forty thousand years in the future, Lobey, a village herder and musician, goes on an Orpheus-like quest into the underworld — in search of his slain lover, Friza. As it turns out, this is a puppet-show of sorts: Lobey is a member of a (three-gendered) alien race who’ve taken on (two-gendered) human forms, and inherited human cultural myths as well. Of the latter, the aliens have made a hodge-podge: the stories of Orpheus, the Minotaur, Billy the Kid, Jean Harlow, Ringo Starr, Jesus Christ — these and other traditions of all dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living. This conceit alone might have made for a terrific mythopoetic sci-fi novel; however, Delaney introduces myriad other issues: genetics, radiation, identity and difference, rural and urban ways of life, perception and reality, life and death, dragons… too much, perhaps, for a relatively short novel. Delany’s prose style, too, confounds: sometimes improvisational and snappy, sometimes ham-fisted pulp fiction. The Einstein Intersection is pretentious — but in the best possible way. Don’t give up on it! Once you encounter Kid Death, you’ll be hooked. Fun fact: Winner of the 1967 Nebula Award for Best Science Fiction Book.

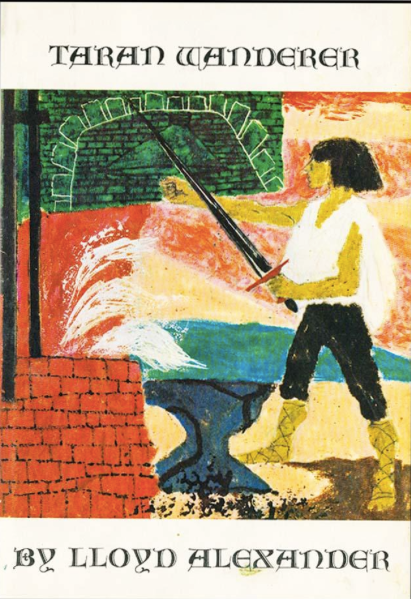

- Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain YA fantasy adventure Taran Wanderer. Some fans of Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain enjoy this installment the least: Taran’s quest — to discover whether he is of noble or common blood — has little urgency; there aren’t any battles with the forces of Arawn Death-Lord; and Eilonwy, the hot-tempered witch-princess who shared in all of Taran’s previous adventures, scarcely makes an appearance. Still, Taran meets interesting people, learns new skills and crafts, and gets into some tough scrapes; for comic relief, he’s accompanied by the shaggy hominid Gurgi, the would-be bard Fflewddur Fflam, and the cranky dwarf Doli. This is a Bildungsroman, and Alexander makes Taran’s education — he studies with a blacksmith, a weaver, a shepherd, a potter, and a truly inspiring and marvelous tinkerer named Llonio, each of whom teaches him something about his own character — fascinating to readers. Oh, and Taran battles a wizard! Fun fact: Alexander originally intended to write four books in the Chronicles of Prydain series; but after publishing The Castle of Llyr, his editor persuaded him to write a book before The High King — one which would persuade readers that Taran had developed into someone deeper and wiser than a courageous Assistant Pig-Keeper.

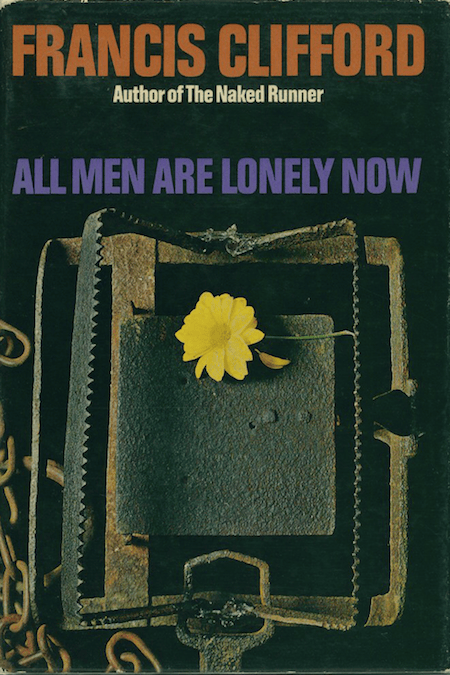

- Francis Clifford’s All Men Are Lonely Now. David Lancaster, an aide in the Ministry of Defense’s Weapons Coordination department, has fallen in love with Catherine, his new boss’s secretary. When a security leak is discovered in the department — someone at Weapons is passing information about a laser-guided missile, code-named “Roman Candle,” to the East — Lancaster finds stolen documents stashed in the briefcase of Hearne, a colleague at Weapons. At this point, halfway through the novel, our perspective suddenly changes. By the end of the book, Lancaster isn’t sure if he’s playing his superiors… or being played by them. The last few pages are devastating. Fun fact: The Los Angeles Times called All Men Are Lonely Now the best espionage novel of the decade. With Clifford’s The Blind Side (1971) and Amigo, Amigo (1973), it forms a trilogy of sorts: the three novels deal with the conflicting demands of loyalty.

- John Christopher’s The White Mountains. The first installment in John Christopher’s Tripods trilogy is among my all-time favorite YA adventures. In the not-too-distant future, 13-year-old Will decides to leave his home town (somewhere in England) rather than go through with the Capping ceremony — a coming-of-age process whereby adolescents’ heads are fitted with a docility-ensuring metallic mesh, by three-legged metal creatures known as Tripods. His cousin Henry, with whom he doesn’t get along, joins him… and on their way across Europe to the Alps (the titular White Mountains), they also meet a French boy, Jean-Paul, who is skinny and frail but a sharp-witted student of the abandoned technologies they discover on their trip. Slowly, we discover that the Tripods are alien invaders who’ve decimated and enslaved humankind, compelling them to return to a pre-industrial way of life. Adults are of no use, when it comes to resisting the Tripods, because they’ve all been capped… except for a few rebels in the Alps. Christopher is a masterful world-builder; and he specializes in realistic teen protagonists, who tend to be jerks (petty, prideful, competitive) until they get over themselves. Fun fact: The White Mountains was followed by The City of Gold and Lead (1967) and The Pool of Fire (1968). The 1988 prequel, When the Tripods Came, isn’t as thrilling — though it uncannily predicts the British children’s TV programs Teletubbies (1997–2001) and Boohbah (2003–2006).

- S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, at some point in the mid-1960s, two rival teen gangs, the working-class Greasers and the middle-class Socs (“Socials”), clash by night — again and again. It’s all fun and games, sorta, until the Socs attempt to drown Ponyboy, the story’s innocent Greaser narrator, in a park fountain; Ponyboy’s friend Johnny kills one of the Socs — and the two go on the lam. Before this happens, however, we get to know the Greasers — Ponyboy’s brothers Darry and Sodapop, who are raising Ponyboy; Two-Bit Matthews; the vicious Dallas “Dally” Winston — as well as the beautiful Cherry Valance, ex-girlfriend of the Soc who is killed. (Ponyboy’s harmless friendship with Cherry is what almost gets him drowned.) Still to come: a fire, a death, a rumble to end all rumbles, and a suicide-by-cop. Awesome. Fun fact: Hinton wrote The Outsiders when she was in 10th and 11th grade; she was 18 when the book was published. Adapted in 1983, by Francis Ford Coppola, as a popular movie starring C. Thomas Howell, Rob Lowe, Emilio Estevez, Matt Dillon, Tom Cruise, Patrick Swayze, Ralph Macchio, and Diane Lane.

- Hugo Pratt‘s Una ballata del mare salato (Ballad of The Salt Sea). In 1914, just prior to the outbreak of World War I, a sinister rogue named Rasputin is up to no good, circumnavigating the islands north of Australia in a catamaran crewed by Melanesian natives, when he picks up a sailor who’s been marooned by his own crew: Corto Maltese. (This is an anti-heroic entrance worthy of John Wayne’s in Stagecoach.) In subsequent adventures, we’ll learn that Maltese, the son of a British sailor and an Andalusian–Romani witch and prostitute, was born in Malta, participated in the Russo-Japanese War, and sympathizes with underdogs… but in this, the first Corto Maltese adventure, he is a pirate. Ballad of The Salt Sea is a tangled yarn — pirates, a German lieutenant, cannibals, wealthy Australian heirs held for ransom, a young Maori navigator, and an evil criminal genius in a hooded cloak all play important roles. Everyone betrays everyone else; Corto Maltese himself, though likable, can’t be trusted. Fun fact: Pratt’s artwork is gorgeous — the missing link between Milt Caniff and Frank Miller — and exegetes claim that he did extensive research, on everything from native tattooings to warships. Along with the first Tintin and Asterix books, Ballad of The Salt Sea was voted by the French public as one of Le Monde’s “100 Books of the Century”.

- Alistair MacLean’s Where Eagles Dare. Not as great as MacLean’s The Guns of Navarone (1957), for sure; in fact, this one might not even be one of MacLean’s top 10 adventures. However, Where Eagles Dare is based on the author’s screenplay (commissioned by Richard Burton) for a terrific movie… so it’s well worth reading. Shortly before D-Day, a US Army General responsible for planning the invasion of Normandy, is captured by the Germans and imprisoned in a fortress high in the Alps of southern Bavaria. Britain’s MI6 parachutes British Major John Smith, U.S. Army Ranger Lieutenant Morris Schaffer, and several other commandoes into Bavaria, to rescue him. As they make their way up forbidding mountains and into the heavily guarded fortress, they discover that one or more of their own number are double agents — but who? Is their mission what it seems to be? Can anyone, at all, be trusted? Fun fact: The 1968 movie — not an adaptation, since the screenplay was written before the novel — starred Richard Burton, Clint Eastwood, and Mary Ure. The movie boasts Eastwood’s highest on-screen body count. Although Glenn Danzig borrowed the title of the Misfits’ 1979 song “Where Eagles Dare” from the movie, the song isn’t about the movie.

- Alan Garner’s YA fantasy adventure The Owl Service. Set in modern Wales, The Owl Service — the title refers not to some kind of elite strigine task force, but to a set of dinner plates with an owl pattern — is a contemporary “expression” of the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion, the earliest prose literature of Britain. Blodeuwedd, in Welsh mythology, is a woman created from flowers, by the magicians Math and Gwydion — for Lleu, a man cursed to take no human wife. Blodeuwedd betrays Lleu in favour of another man, Gronw, who kills Lleu; as punishment, Blodeuwedd is turned into an owl. In Garner’s story, a 15-year-old girl and her new stepbrother are vacationing in rural Wales, where they befriend a local teenage boy. They discover an owl-patterned dinner service… which apparently is cursed, because the next thing you know, the three possessed teens are helplessly, inexorably re-enacting the Blodeuwedd story. Fun fact: Winner of both the Carnegie Medal and Guardian Award for children’s literature. The Owl Service was adapted as a well-regarded BBC miniseries in 1969–1970. Garner’s other YA fantasy novels — The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960), The Moon of Gomrath (1963), Elidor (1965) — are excellent; so is Red Shift (1973).

- Ishmael Reed‘s The Freelance Pallbearers. In an alternate-universe version of New York, Bukka Doopeyduk is a young black man hustling to survive in HARRY SAM — a kingdom ruled by Harry Sam, a despotic used car salesman who hasn’t left the bathroom in 30 years. Infected by the HooDoo — a trickster virus, of sorts — Doopeyduk rebels against not merely the oppressive political situation, but the entire Western/European/Christian social and cultural apparatus, which he recognizes as repressive and fucked-up. Quitting his job as a nursing home “psychiatric technician,” Doopeyduk sets out to foment a revolution against Harry Sam. Along the way, Doopeyduk points out the foibles of the black community’s other would-be leaders, from a Nation of Islam-esque nationalist who secretly eats pork, to black ministers whose actions are anything but godly. HARRY SAM’s black community, in Doopeyduk’s telling, is doomed to fall victim to one weird obsession and con job after another; but of course, Doopeyduk himself is a con artist — code-switching, praising Jesus, you name it. By any means necessary, right? Fun fact: As with Reed’s subsequent novels, The Freelance Pallbearers satirizes popular African-American narratives… in this case, autobiographies like Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery and The Autobiography of Malcolm X, not to mention confessional novels by celebrated black authors like Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin. PS: Reed is a major influence on one of my favorite contemporary novelists, the brilliant Paul Beatty.

Note that 1968 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Sixties. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Sixties; the titles on my 1968 and 1969 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Sixties adventure writing is all about: self-reflexive, postmodernist, sardonic inversions of the adventure genre; plus New Wave science fiction.

- Charles Portis’s western adventure True Grit. Mattie Ross, a narrator whose lack of humor makes the absurdities of her story’s larger-than-life characters all the more delicious, recounts her efforts — many years earlier, in 1873, at age 14 — to revenge herself upon her father’s killer, who has fled from western-central Arkansas into Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). In Fort Smith, Mattie hires an aging, hard-drinking, one-eyed marshal, Reuben J. “Rooster” Cogburn; and insists on accompanying him. Her odyssey has been compared to Huck Finn’s, thanks to the gorgeous regionalisms and figures of speech it captures. Rooster and Mattie are joined by LaBoeuf, a self-satisfied Texas Ranger also seeking the killer — at which point the novel veers into crackerjack territory, as the old-timer demonstrates that “true grit” more than makes up for relatively clumsy, brutal craft. The action is bloody and exciting, but Mattie’s voice — intelligent, dry, cantankerous — is the real attraction here. Is this a revisionist western? I don’t think so. Instead, Portis (who didn’t consider this his best book) is demonstrating how western adventures should have been written in the first place. Fun facts: John Wayne would win a Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Rooster Cogburn in the 1969 movie adaptation; the 2010 Coen Brothers adaptation is excellent.

- Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö’s police procedural Den skrattande polisen (The Laughing Policeman). Why did a gunman kill eight people — including Detective Åke Stenström, from the special homicide commission of the Swedish national police — on a Stockholm bus? Stenström’s colleagues — including phlegmatic Martin Beck and left-leaning Lennart Kollberg — investigate. Despite tremendous political pressure — because massacres like this are extremely rare in Sweden — the cops painstakingly, even ploddingly follow one lead after another. Eventually, the come to suspect that the intended victim was Stenström — who in his spare time was investigating the murder of a Portuguese prostitute sixteen years earlier. This is the fourth in Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s so-called Martin Beck series; and it’s considered one of the best. Fun facts: The Laughing Policeman won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. The novel was adapted as a movie in 1973; set in San Francisco, it stars Walter Matthau and Bruce Dern.

- Samuel R. Delany’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Nova. In the year 3172, interstellar human society is divided into three constellations — each of which was originally colonized by different Earth socio-economic classes. Draco, which includes Earth and other wealthy planets, is an aristocratic constellation ruled by the (caucasian) Red family, whose Red-Shift Limited is the sole manufacturer of faster-than-light drives; the Pleiades Federation, a middle-class constellation, is the home of operations for the rival (mixed-race) Von Rays. The Outer Colonies, settled by working-class Earthlings, are the source of the important energy source illyrion, a superheavy element essential to starship travel and terraforming planets. Our protagonist is Lorq Von Ray, a playboy who — years earlier — was attacked and scarred by Prince Red. Now a nihilistic, revenge-obsessed adventurer, Lorq puts together an Argonauts-inflected squad of hippie-ish misfits — the Mouse, Lynceos, Idas, Tyÿ, Sebastian, Katin — and takes them on a demented voyage to the heart of an imploding star… in order to capture an enormous amount of illyrion, and in so doing destroy Draco’s control of the Outer Colonies. Though the plot is only intermittently thrilling (in a space-opera way), the language is gorgeous, the meta-textual references (to Moby Dick, Arthurian mythos, and more) are pretty fun, and there’s a whole Tarot-really-works conceit that’s almost persuasive. If Delany weren’t an experimentalist, this could have been a Dune; I’m glad it isn’t. Fun facts: There’s a cyberpunk tech aspect to the book that I can’t get into, here; William Gibson’s Neuromancer alludes to Nova. After this book, Delany didn’t publish again until Dhalgren appeared in 1975.

- Ursula K. Le Guin‘s fantasy adventure A Wizard of Earthsea. In the world of Earthsea, magic is an inborn talent — and those born with the most powerful gifts are sent to school on the island of Roke, where they are trained to become responsible, staff-carrying wizards. (Hello, Harry Potter.) Ged, a reddish-skinned shepherd boy, is trained by the humble mage Ogion to use his impressive powers in harmony with nature; however, Ged is impatient and reckless. (Hello, Ben Kenobi and Luke Skywalker — not to mention Qui-Gon Jinn and Anakin.) At Roke, Ged shows off to his fellow students by releasing a shadow creature that attacks him. Injured and afraid, he leaves school and seeks wizard work (including protecting a village from dragons!) while also evading the shadow creature, which continues to haunt him… until his old teacher, Ogion, advises Ged to confront his fears. Fun facts: This is Le Guin’s first book for a young adult audience; Margaret Atwood has called it one of the “wellsprings” of fantasy literature. The next two installments in the Earthsea Trilogy are The Tombs of Atuan (1970/1971) and The Farthest Shore (1972). Later books in the Earthsea cycle: Tehanu, Tales from Earthsea, and The Other Wind. In 2005, Le Guin expressed her disappointment when the Sci Fi Channel’s loose adaptation of the Earthsea trilogy cast a white actor as Ged.

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. In a post-apocalyptic San Francisco, bounty hunter Rick Deckard is charged with “retiring” six escaped androids — one of whom, named Pris, moved into a derelict apartment building inhabited only by John Isidore, an intellectually challenged man who attempts to befriend her. Although there are plenty of thrills and chills here (for example, Deckard is seduced by an android whose mission it is to make it impossible for him to kill Pris), this is as much a philosophical novel about empathy as it as an adventure. The androids have no emotions — the only way that Deckard can tell them apart from humans is by giving them empathy tests. The androids, meanwhile, are on a mission to disprove a popular pseudo-religion called “Mercerism,” in which grasping the handles of an electronic Empathy Box allows you to “encompass every other living thing.” (“Mercerism is a swindle,” the androids insist. “The whole experience of empathy is a swindle.”) Deckard must prove them wrong… though he begins to wonder whether he, too, is an android. Fun facts: The theatrical-release version of Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s souped-up adaptation of Dick’s novel, doesn’t lead viewers to question Deckard’s humanity (or does it). And the 2017 sequel, Blade Runner 2049, further muddies the waters.

- Peter Dickinson’s YA sci-fi/fantasy adventure The Weathermonger. A teenage boy, Geoffrey, snaps out of a fugue state — in which he’s been for years — and discovers that he’s been working as a “weathermonger” for an English village on the Channel… but now they think he’s a witch, and they want to kill him. He and his younger sister, Sally, escape across the water to France. What’s going on? Several years earlier, a mysterious force has converted most of England’s population to anti-technology zealots, and the country has reverted a quasi-medieval way of life. Unaffected people have fled for the continent. France and other European countries have been unable to figure out the cause of the “changes,” and adults who’ve parachuted in to investigate haven’t returned. So Geoffrey and Sally return to England, and drive a 1909 Rolls Royce Silver Ghost — whose workings are described in loving detail — towards an atmospheric disturbance emanating from the Welsh coast. Fun facts: Hopefully it isn’t giving too much away to reveal that this book — not so much the other two in the trilogy — concerns what’s known as The Matter of Britain. Chronologically, this is the final installment in Dickinson’s excellent Changes trilogy; however, it was published first.

- James Blish’s fantasy adventure Black Easter, or Faust Aleph-null. A fascinating novella about an arms dealer who hires a black magician, Theron Ware, to assassinate California’s Governor “Rogan” before unleashing all the demons of Hell. In this alternate Earth, sorcery and the ritual magic for summoning demons, as described in Ramon Llull’s Ars Magna (1305), say, or the Enchiridion of Pope Leo (c. 1633), work. That’s kind of the whole plot, but the framework of rules and regulations within which the magicians operate is persuasive; and Ware is a compelling character. His description of black magic as a science and an art reminds me of my own field, commercial semiotics: “Given [the right] books, you could learn almost everything I know in a year. To make something of the material, of course, you’d have to have the talent, since magic is also an art. With books and the gift, you could become a magician… in about twenty years. If it didn’t kill you first, of course…. It takes that long to develop the skills involved.” A group of white magicians — named after sci-fi authors, ha ha — are powerless to intercede. Fun facts: A version was serialized as Faust aleph-null in If magazine. Black Easter, often published with its sequel, The Day After Judgment, is part of the After Such Knowledge trilogy — which concerns the unanticipated consequences of the search for new knowledge.

- Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain YA fantasy adventure The High King. The final installment in Alexander’s terrific Prydain cycle begins shortly after the events of Taran Wanderer. Dyrnwyn, the magical black sword of Gwydion, Prince of Don, has been stolen by the necromancer Arawn. Tara, Gwydion, Eilonwy, Fflewddur Fflam, Gurgi, the hapless Rhun, and even the peaceful pig-keeper Coll head out to retrieve it. Their quest turns into an all-out assault on Arawn’s kingdom — the Fair Folk, the northern realms, and the Free Commots, the smiths and weavers whom Taran befriended while seeking his own identity, the creatures of air and land all flock to the banner of the White Pig. Characters we’ve come to know and love don’t survive; magic fades. What will become of Prydain — and Taran, Assistant Pig-Keeper? Fun facts: The High King was awarded the 1969 Newbery Medal for excellence in American children’s literature.

- Lionel Davidson’s political thriller Making Good Again. James Raison, a British lawyer representing the daughter of Bamberger, a long-missing German-Jewish banker, arrives in West Germany to settle a reparations case with the government — which was a controversial topic at the time. (The book’s title is a literal translation of the German term for the restitution payments made to Holocaust survivors.) There are two other lawyers on the case: Heintz Haffner, a German who claims he avoided joining the Nazi party; and Grunwald, a rabbi and lawyer from Israel who has a lien on some of Bamberger’s money for a refugee organization. Bamberger’s money was deposited in a Swiss bank in 1947 — what happened to it, and to Bamberger? Wearing disguises and traveling through the Bavarian forest, Raison and his unlikely comrades confront echoes of Nazism and ponder questions about German guilt. All of which sounds deadly serious — but it’s also thrilling, and funny. Fun facts: Davidson, a British-born Jewish writer who served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War and eventually moved to Israel, won the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger Award three times.

- John Christopher’s YA science fiction adventure The Pool of Fire. In the thrilling conclusion to Christopher’s Tripods trilogy, young Will helps organize resistance against the alien invaders who’ve subjugated the human race… and then the uprising begins. Will, the series’ flawed protagonist, has spent months inside one of the Tripods’ domed cities (as detailed in the previous book, The City of Gold and Lead); now, he and Fritz travel across Europe and the Middle East setting up anti-Tripod terrorist cells. Once the Resistance discovers that alcohol has a strongly soporific effect on the aliens, they plan a simultaneous commando raid against all of the Tripod cities on Earth. The Panama city holds out… so Will, Fritz, and Henry lead an attack launched from hot air balloons. One of the friends sacrifices himself to destroy the final redoubt. Now that their common enemy has been vanquished, will humankind remain united — or will they revert to national rivalry and war? Fun facts: The Tripods trilogy was serialized in comic strip form in the Boy Scouts’ magazine Boys’ Life, from 1981–1986. John Christopher (real name: Sam Youd) is also the author of the terrific Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1970–1972).

- Ishmael Reed’s satirical Western adventure Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down. Five years before Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles, the brilliant satirist, political philosopher, and prose stylist Ishmael Reed gave us this surrealist, provocative, fragmentary horse opera about the Loop Garoo Kid, a black circus cowboy, Neo-HooDoo houngan, and trickster who battles Drag Gibson, an evil capitalist rancher and tyrant of Yellow Back Radio, a Sergio Leone-esque ghost town. Along with Chief Showcase, a stylish Native American master of subversive survivalism, the Loop Garoo Kid also does battle with the oppressive and repressive elements of white Christian culture, which is to say, with pretty much every aspect of life as it is experienced by black Americans. Other antic characters include Bo Schmo, guru to a “neo-social realist” gang; Pope Innocent, God’s fixer; and Mustache Sal, a murderous mail-order-bride. Western myths are subverted (the novel’s title references the yellow covers of dime Westerns), obscenely. All of this takes place in a time warp, spanning three centuries of US history. Which, I suppose, makes Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down a sort of science-fiction novel, as well. Fun facts: Darryl Pinckney described Reed’s notion of Neo-HooDooism as “a literary version of black cultural nationalism determined to find its origins in history…. Neo-HooDooism, then, is a school of revisionism in which Reed passes control to the otherwise powerless, and black history becomes one big saga of revenge.”

- Kurt Vonnegut’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death. Much like the bumbling protagonist of Jaroslav Hašek’s pioneering antiwar novel The Good Soldier Švejk (1921–1923), Billy Pilgrim is an ill-trained, disoriented, cowardly chaplain’s assistant. During the Battle of the Bulge in 1944, he is captured and transported to Dresden. In 1945, as British and American bombers dropped several thousand tons of high-explosive bombs and incendiary devices on the city, Pilgrim and his fellow prisoners and their guards take refuge in a cellar beneath Schlachthof-fünf, the titular “slaughterhouse five”; they are among the only survivors of the (still-controversial) attack. We experience all of this in flash-backs or flash-forwards, because Billy has become “unstuck in time,” not to mention in space. At one point, years later, on his daughter’s wedding night, Billy is captured by aliens and transported to Tralfamadore, the fatalistic residents of which can observe all points in the space-time continuum simultaneously. Like them, Billy becomes a philosophical ironist because — thanks to his time-traveling — the entire human experience strikes him as absurd. Is he crazy, or a visionary? Fun facts: As a prisoner of war in 1945, Vonnegut experienced the Dresden firebombing; the narrator of Slaughterhouse-Five is the author, speaking in his own voice. The 1972 film adaptation, directed by George Roy Hill (in between directing Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting), won the Prix du Jury at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival.

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Left Hand of Darkness. This is the second of the author’s so-called Hainish Cycle, set in a galaxy whose human population evolved on Hain, then spread outwards to many other planets (including Earth) before, at some distant point in the past, losing contact. Efforts have been mounted to re-establish a galactic civilization; some eighty planets have organized themselves into a union called the Ekumen. In this novel, Genly Ai, an agent of The Ekumen, has spent a frustrating couple of years as an envoy to the frozen planet Gethen. Ai’s efforts to recruit Gethen into the Ekumen have failed… because his supposedly enlightened worldview is structured by binary oppositions. Gethenians, because they are ambisexual — they only adopt sexual attributes once a month, during a period of sexual receptiveness and high fertility — see the world in an entirely different way. Ai only begins to empathize with the Gethenian worldview once he escapes from prison with Estraven, an exiled Gethenian politician, who not only helps Ai survive a trek across the planet’s wintry wilderness, but helps him understand his own deep-seated prejudices and assumptions about gender and gender roles. Fun facts: The Left Hand of Darkness is one of the first feminist sci-fi novels, though some feminists have argued that it does not go far enough in critiquing gender stereotypes. Harold Bloom said, of this book, which won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards: “Le Guin, more than Tolkien, has raised fantasy into high literature, for our time.”

- Elmore Leonard’s Jack Ryan crime adventure The Big Bounce. Elmore Leonard’s first novels, published in the Fifties, were westerns. He wrote The Big Bounce, his first crime novel, in 1966, but couldn’t get it published until 1969, after it was adapted as the 1969 movie of the same title, starring Ryan O’Neal. When Jack Ryan, washed-up ballplayer and small-time thief, is hired as a Florida beach resort handyman, he’s quickly seduced by Nancy, a millionaire’s mistress who turns out to be something of a sociopath (or psychopath). Nancy wants Jack to steal a $50,000 payroll from her lover, and he goes along with the plan… which quickly gets complicated, of course. Nancy isn’t telling Jack everything; Jack, meanwhile, is being pursued by a couple of hoods to whom he owes money from his last caper. Readers who enjoy Leonard’s better-known novels, like Swag, Cat Chaser, Stick, LaBrava, and Get Shorty, may be disappointed by how unsympathetic our protagonists are, here; however, Leonard’s characteristic humor and laconic prose style are very much in evidence, as is his tendency to let his characters take the plot where they will — even at the risk of an ending that may not be entirely satisfying to most crime novel fans. Fun facts: The Big Bounce was adapted a second time — as a comedy heist film — in 2004 by George Armitage. Like the 1969 version, it was a flop. The character Jack Ryan would return in Leonard’s 1977 book Unknown Man #89.

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Ubik. Joe Chip works for Runciter Associates, which employs “inertials” — telepaths and precogs with the ability to block the powers of other, less scrupulous telepaths and precogs — to protect the privacy of their clients. He’s one of Dick’s “minor men,” unable to manage his own life; in fact, he owes money to his own front door! Joe has a thing for his new colleague, Pat, who can change the past in such a way that people don’t realize it. Sent to Luna in search of criminal telepaths, Joe and Pat and the rest of their team is caught in an explosion… after which nothing is ever the same again. Are they moving backwards in time? Are they in some other reality? Are they caught up in a cosmic battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness — and if so, what is the ultimate source of these forces? Every interpretation that they posit is frustrated; meaning remains elusive. Each chapter is prefaced with an advertisement for Ubik, salvation in a spray can. This is, perhaps, the ultimate example of one of Dick’s apophenic sci-fi potboilers. Fun fact: Ubik inspired France’s Alfred Jarry-inspired Collège du Pataphysique to elect Dick as an honorary member. John Lennon, at one point, was interested in adapting the film version.

- Anne McCaffrey’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Ship Who Sang. Before Iain M. Banks’s (or Becky Chambers’ or Ann Leckie’s) independent AI starships there was The Ship Who Sang. Our protagonist is Helva, who was born with an exceptional brain and severe physical disabilities… so she was raised as an indentured servant destined to be a starship brain. One with a lamentable tendency to fall in love with her human co-pilot (known as the “brawn” to her “brain”) as they travel the galaxy on various missions of mercy. What happens if the brawn loves her back… and wants to have sex with her? Helva’s feelings of love and loss are poignant; however, the whole set-up is also a bit creepy and offensive! If you think about the sex scenes in McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series, you’ll begin to see why. Fun fact: The book’s first five chapters were originally published as “The Ship Who Sang” (1961; McCaffrey’s own favorite story), “The Ship Who Mourned” (1966), “The Ship Who Killed” (1966), “Dramatic Mission” (1969), and “The Ship Who Disappeared” (1969); the sixth chapter is original to the novel. In the 1990s, McCaffrey and co-authors produced six sequels.

- Vladimir Nabokov’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Ada, or Ardor. When he is fourteen, Van Veen, who will grow up to be a psychologist and renegade scholar, falls in love with his eleven-year-old cousin, Ada; they begin a life-long sexual affair, despite later discovering that they are half-siblings. The story begins in the early 19th century, though characters discuss airplanes, motion pictures, and other anachronistic technologies; everything is powered by water, and it is forbidden to mention electricity. Reference is made to an historical catastrophe referred to as “the L disaster,” which has somehow “everted” (I borrow the term from a 1975 essay about this novel in Science Fiction Studies) time, earth, and sexual gender. Van and Ada — who are maybe somehow, respectively, Eve and Adam — live on a planet known as Antiterra, which is geographically similar to Earth, although politically England has conquered most of it, and American culture is influenced by Russia. Nineteen-Sixties culture is, somehow, a myth from the past. Trippy! Fun facts: Ted Gioia has compared Ada to Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle and other alternate-history works of science fiction. I might include works by Samuel R. Delany and Michael Moorcock in which the Beatles become mythical figures.

- Jane Gaskell’s New Wave sci-fi adventure A Sweet, Sweet Summer. Enormous alien spacecrafts are hovering over London, Birmingham, and Manchester, sealing Britain off from the outside world; one of the aliens’ first demonstrations of power was the public execution of Ringo Starr. It’s a weird scene: “People rush under [the alien craft] when the rain starts so municipal authorities have erected seats and slot-machine arcades under them and charge you for using them.” The country descends into anarchy, as communist and fascist militias battle in the streets, and hoodlums terrorize the defenseless. Our narrator, Rat, is an unpleasant, misogynistic character who runs a tiny London boarding house and brothel. The alien invasion is the best thing that ever happened to him, so when his charismatic, gender-ambiguous, proto-punk cousin, Frijja, shows up and attempts to free London from alien oppression, Rat does what he can to thwart her — while also strugling to defend his turf from a marauding gang… with whose thuggish leader he is disturbingly fascinated. Fun fact: An exceedingly difficult book to find! China Miéville says that A Sweet, Sweet Summer “perfectly combines psychological perspicacity and social critique in an unusual dystopian future London.” Gaskell also wrote a seminal YA vampire novel: 1964’s freaky The Shiny Narrow Grin.

- John Bellairs’s fantasy adventure The Face in the Frost. When ominous supernatural phenomena come to the attention of Prospero, an accomplished but misfit wizard, he and his adventurer friend Roger Bacon head out to seek their source. There’s a slowly building atmosphere of menace, within a beautifully realized fantasy world of ghosts, chimaeras, and other nightmares. The elderly protagonists are a delight: sarcastic, crochety, courageous, given to spell-casting in allusive doggerel verse. The writing is gorgeous and full of sly anachronisms and meta-fictional references not only to Shakespeare and the “Cinderella” fairy tale, but to Lovecraft and Tolkien as well. The novella’s episodic plot feels like a Dungeons & Dragons adventure — there’s a haunted grove, a murderous innkeeper, weaponized weather, and a magical artifact that everyone’s after. In fact, Gary Gygax’s Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide lists The Face in the Frost as recommended reading; Prospero’s practice of studying his book of spells the night before he might need them no doubt helped inspired the game’s requirement for Magic Users to do so. Although Bellairs’s Lewis Barnavelt/Rose Rita Pottinger adventures are terrific, this is his only fantasy novel for adults. Fun facts: This is a fantasy novelist’s fantasy novel. Lin Carter praised The Face in the Frost as one of the best fantasy novels to be published since The Lord of the Rings. Ursula K. LeGuin described it as “authentic fantasy by a writer who knows what wizardry is all about.”

- Richard Stark’s Parker crime adventure The Sour Lemon Score. Parker’s twelfth outing is a return to form — in fact, it boasts more or less the same plot as the first Parker novel, The Hunter, though it’s quite a bit darker and more violent. The ruthless criminal Parker and three associates rob a bank, and make their getaway… but when the take is lower than they’d expected, George Uhl, whom Parker didn’t trust from the beginning, starts shooting. The caper has gone sour as a lemon, and the story now turns into a hunted-man adventure, with Parker in the role of the relentless hunter. Will Parker get his money back, punish Uhl, and make it home safely to Claire — the girlfriend he first met in 1968’s The Rare Coin Score? Maybe not! After all, Uhl is very good at hiding out… and there’s another dangerous crook, who gets wind of Uhl’s loot, for Parker to contend with as well. Fun facts: The Sour Lemon Score is one of five novels published in 1969 by the prolific Stark (Donald E. Westlake); the others are Somebody Owes Me Money, Up Your Banners (a race-relations comedy set in a New York public school), and The Dame and The Blackbird (both starring Alan Grofield, an actor and heist man who appears in some Parker novels). He’d publish another five novels in 1970!

- Philip K. Dick‘s New Wave science fiction adventure A Maze of Death. A naturalist, a typist, a linguist, a geologist, and ten other colonists living on the mysterious planet Delmak-O — or supposedly on Delmak-O — begin to kill themselves, or get killed. Are they criminally insane and part of a psychiatric experiment? Are they the crew of a spaceship that has become stranded in orbit around a dead star? Can the deities of their religion really be contacted through a network of prayer amplifiers, or is this part of the hallucination? What’s the deal with the gelatinous 3-D printers known as “tenches”?

- Peter Dickinson’s YA fantasy adventure The Devil’s Children. Part of the author’s excellent Changes trilogy, about life in a future England which has suddenly reverted to a medieval-type social order and way of life. We don’t discover why that happened, in this book — we do in The Weathermonger (1968); instead, we witness the Changes through the eyes of a streetwise 12-year-old English girl, Nicky. Having run away from home, Nicky joins a wandering group of Sikhs — who, in post-Changes England, are considered “devil’s children” — and assists them as they establish themselves in a new home in a farming community. When raiders attack the farmers, the Sikhs come to the rescue. Fun fact: Although it was published third in the Changes series, The Devil’s Children is chronologically the earliest.

- Poul Anderson‘s New Wave science fiction adventure Tau Zero. When the colonization starship Leonora Christine is caught in an uncontrollable acceleration, the reader learns a lot about relativity and time dilation, not to mention details about the ship’s engines and radiation shielding. The crew’s original plan was to spend five years in transit, during which time 33 years would have passed on Earth; instead, they travel millions (billions?) of years into the future. While the universe outside the ship prepares to collapse and re-Big Bang, the ship’s constable must maintain order and morale among the crew. It’s a kind of On the Beach story, set in outer space. Fun fact: Anderson’s novel is regarded as a quintessential example of technology-driven “hard” sci-fi.

- Mary Stewart’s Arthurian fantasy adventure The Crystal Cave. In this education-of-a-wizard prequel to the legend of King Arthur, Merlin, a neglected Welsh boy, is taught to use his psychic and practical powers by an Obi Wan Kenobi-like hermit. He joins the court of Ambrosius, who, supported by his brother Uther, plans to invade and unify Britain. Merlin is then captured by the Saxon high king, who plans to sacrifice him. Fun fact: Stewart was best known as the author of popular romantic suspense novels until the publication of The Crystal Cave, the first in what would be a bestselling Arthurian quintet of novels.

- John Sladek’s New Wave science-fiction adventure The Müller-Fokker Effect (1970). While his persona is being recorded as computer data, Bob Shairp, a government worker, dies in a freak accident. Can he be reconstructed? That’s the ostensible plot of Sladek’s romp across late Sixties America — which satirizes then-burgeoning right-wing forces in the military, evangelism, and radical anticommunist groups. (Ronald Reagan, of all people, is president!) Long before Iain M. Banks and others explored the possibilities of mind uploading, Sladek conjures up a scenario in which Shairp’s persona-data is encoded into a virus, which is then used to infect a host body. Fun fact: The book’s title, in case you haven’t already guessed, is an obscene pun.

- James Dickey’s atavistic wilderness-survival adventure Deliverance. On a back-to-nature canoe trip, a group of Southern businessmen (who feel emasculated by their bourgeois lifestyles) are sexually assaulted by hillbillies. The trip’s leader, Lewis, a survivalist type, comes to the rescue… but then he breaks his leg. So the ill-equipped group must canoe the treacherous river, battle the hillbillies (with bow and arrow), then cover up the entire affair. Fun fact: Adapted as a movie, considered one of the best suspense/thriller films of all time, in 1972 by John Boorman. See my FITTING SHOES post about the tennis shoes worn by this novel’s protagonist.

- John Christopher’s YA science fiction adventure The Prince in Waiting. In a post-apocalyptic future, in which England has reverted to a medieval way of life, complete with an untouchable caste of mutants, thirteen-year-old Luke’s father becomes the Prince of Winchester; Luke is named his successor. All of this is ordained by the Seers, England’s priestly caste, who commune with the Spirits. A few years later, however, Luke’s mother is murdered, his father is killed, and his elder half-brother becomes Prince. Luke flees Winchester, and is taken in to the Sanctuary of the High Seers… where he discovers the truth about them… and the Spirits. Fun fact: This is the first installment in Christopher (Sam Youd)’s excellent Sword of the Spirits trilogy.

- Tony Hillerman’s crime adventure The Blessing Way. The first of the author’s 18 mysteries featuring officers from the Navajo Tribal Police Force boasts a complex plot. McKee, an Indiana Jones-like anthropologist, is researching tales of witches in the sprawling Navajo region of New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah; his colleague, Canfield, is killed. Another researcher, Dr. Hall, is — it turns out — surreptitiously collecting radar data about missiles being tested near the Reservation. Two no-good Navajo men protect Dr. Hall’s scheme by disguising themselves as witches and killing sheep. When the ersatz witches kill a young Navajo man, Lt. Joe Leaphorn of the Navajo Tribal Police gets involved. Fun fact: Hillerman was hailed for having “reinvented the mystery novel as a venue for the exploration and celebration of Native American history, culture and identity.”

- J.G. Farrell’s Troubles. Less an adventure than a sardonic inversion of the cozy catastrophe genre. Near the beginning of the 1919–1921 Irish War of Independence, Major Brendan Archer, recently discharged from the British Army, arrives at the enormous, dilapidated Majestic Hotel in south-east Ireland. Archer may or may not be engaged to the daughter of the hotel’s owner; hers is an Anglo-Irish Protestant family at odds with the local Catholic population. As the novel progresses, the hotel — a symbol of England’s dilapidated empire — decays in a spectacular fashion. Fun fact: In 2010, via a public vote, Troubles, the first instalment in Farrell’s Empire Trilogy, won the Lost Man Booker Prize, a special edition of the Man Booker Prize.

- Joanna Russ‘s New Wave science-fiction adventure And Chaos Died. Two planets come into conflict. One is highly industrialized; creativity and individuality are suppressed; and a police state monitors citizens’ actions. The other is a proto-LeGuin-esque anarchist utopia, on which the natural world is revered, unique individuality is encouraged, and psychic powers have been discovered and nurtured. The latter aspect of the plot gives the novel its trippy, difficult-but-rewarding flavor — because Russ explores exactly what it might feel like to be clairvoyant dropped into a totalitarian culture!

- Victor Canning’s espionage adventure Firecrest. A thriller told from the point of view of John Grimster, who works for a British Ministry of Defence dirty-tricks organization known only as “the Department.” Grimster is a world-weary assassin, who for years has been dispatched to handle, organize, or suppress certain situations and persons, as needed. In this adventure, he’s tasked with persuading Lily, the girlfriend of a recently deceased scientist, to reveal the whereabouts of the scientists’s top-secret papers. However, he ends up protecting Lily from other ruthless agents; and — while continuing to seek the scientists’s missing papers — he investigates the death of his own girlfriend, who recently died in a road accident. (Did the Department have her killed?) Hypnosis plays an important role in the plot; so does fly-fishing! Fun fact: In the 1950s, Canning’s adventure novels were better known than Ian Fleming’s. However, Canning is all but forgotten today. Which is too bad, because his thrillers from 1971–1980 — e.g., The Rainbird Pattern, The Finger of Saturn, the YA novel The Runaways, and even an Arthurian trilogy (!) — are terrific. Forget Fleming, read Canning.

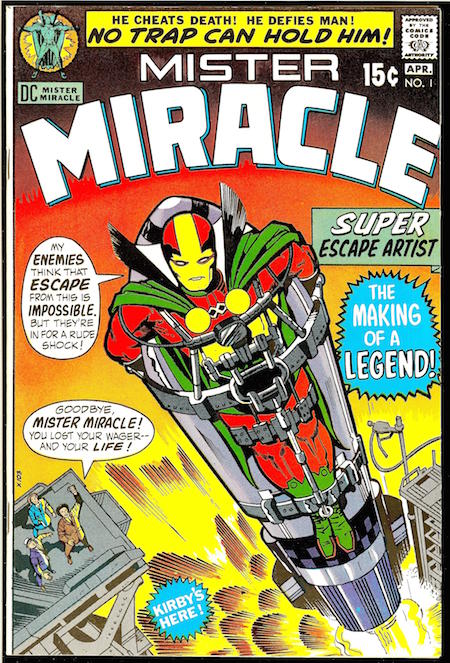

- Jack Kirby‘s Fourth World storyline. When Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics for DC in 1970, he launched a science-fictional epic revolving around aliens with superhuman abilities arriving on Earth. Hailing from the planets Apokolips and New Genesis, the ontogeny of the so-called New Gods — their fantastic powers, even their names — recapitulated Kirby’s imaginative billion-year phylogeny, during which three previous eras (“worlds”) had seen the rise and fall of the Old Gods, legends of whom live on in humankind’s mythologies. So sweeping was Kirby’s weltanschauung that it couldn’t be contained in the New Gods comic (#1–11 written and illustrated by Kirby, 1971–72). So he also wrote and illustrated Forever People (#1–11, 1971–72) and Mister Miracle (#1–18, 1971–74), not to mention a reimagined Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen. These proto-postmodernist comics are a volatile admixture of religion (the character Izaya evokes the biblical Isaiah), ancient-astronaut theories, sci-fi technology (the Boom Tube, the Mobius Chair, the Mother Box), and 1960s culture (the Forever People are cosmic hippies). Kirby’s 1940s-era teen characters, the Newsboy Legion, were resurrected; and Don Rickles made a cameo appearance. Truly awesome. Fun fact: The Fourth World storyline was intended to be a finite series, which would end with the deaths of the characters Darkseid and Orion.

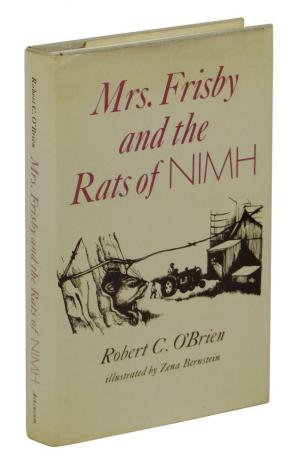

- Robert C. O’Brien’s children’s science-fiction adventure Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH. Inspired by real experiments, conducted from the ’40s through the ’60s at the National Institute of Mental Health, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH imagines what might have happened if a group of super-intelligent rats (and one mouse) had escaped the laboratory and founded a high-tech commune underneath a farmer’s rosebush. That alone would have made a good story… but by making the rats of NIMH’s tale secondary to the desperate struggle of a courageous mouse, Mrs. Frisby, to save her family from the farmer’s plow, O’Brien wrote one of the best kids’ books ever. In addition to the rats’ fascinating society, we encounter a charismatic crow, a sinister cat, and an even more sinister group of scientists posing as rat exterminators. There’s also a philosophical discussion about the commune’s lack of self-sufficiency! Fun facts: Winner of the 1972 Newbery Medal. O’Brien’s other fantasy and sci-fi books — The Silver Crown (1968), A Report from Group 17 (1972), and Z for Zachariah (1974) are also excellent.

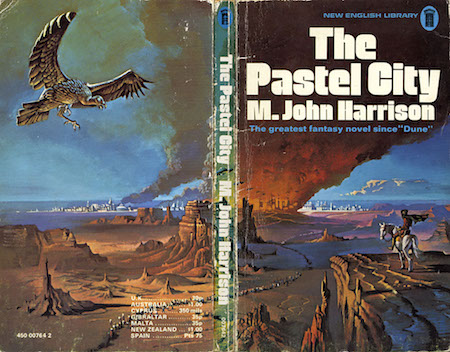

- M. John Harrison’s science fantasy adventure The Pastel City. In the distant future, a medieval-style way of life has risen from the ashes of civilization. There is a barbarian Queen of the North; and, ruling over Viriconium, the ever-changing Pastel City, a beautiful Queen of the South. Scavengers scour the ruins for power blades, energy cannons, and airboats. When news comes that the North plans to deploy scavenged alien automata against the South, a brooding poet-warrior, Lord tergeus-Cormis, travels with a mercenary, Birkin Grif, in search of a mad dwarf who is expert in ancient weaponry. The adventurers encounter mechanical birds, brain eaters, and a wizard of sorts; and they discover that a complex, lethal technology from the past lives on. This is an affectionate, but also sardonic reimagining of the fantasy genre — nothing is resolved, things get murkier instead of more clear, heroes are unheroic. Fun fact: Harrison’s Viriconium series — it includes A Storm of Wings (1980), In Viriconium (1982), and the story collection Viriconium Nights (1985) — has been aptly described as “fantasy without the magic and science fiction without the ‘future’.” PS: John Christopher’s YA Sword of the Spirits trilogy, which could be described the same way, began publication in 1970.

- Ursula K. LeGuin’s science fiction adventure The Lathe of Heaven. Operating under the influence of Philip K. Dick, LeGuin wrote an uncanny, thought-provoking novella about George Orr, a Portland, Oregon man who has begun self-medicating in an attempt to prevent himself from dreaming. Why? Because some of his dreams have been altering reality — and George is the only one who notices. (For everyone else, things have always been the way they are now.) Visiting the well-meaning psychologist and sleep researcher Dr. Huber, George is persuaded to embark on a program of “effective dreaming” aimed at improving the state of the world. Unforeseen consequences ensue. (This will not surprise fans of LeGuin’s fantasy and science fiction, which stresses the ambiguity of every utopian ideal, and the dark forces at work within even the noblest soul.) For example, in an effort to dream about peace on Earth, Orr conjures up a fleet of invading alien spacecraft… which does unite humankind, but at what cost? Also — does the “real world” exist at all, or did Orr dream it up after a 1998 nuclear war? Fun fact: First serialized in Amazing Science Fiction Stories, March 1971 and May 1971. The book has sci-fi elements — it’s set in 2002, Dr. Huber employs a device called the Augmentor — but it’s fantastical. The 1980 PBS production of The Lathe of Heaven was well-regarded; LeGuin was closely involved.

- Frederick Forsyth’s assassination thriller The Day of the Jackal. In 1961, when Charles de Gaulle organized a referendum on self-determination concerning Algeria, the OAS — a paramilitary group determined to keep Algeria French — decided to assassinate him. They made six attempts on his life; by 1962–1963, therefore, De Gaulle was the most heavily guarded man alive. Forsyth’s debut novel, set in 1962–1963, speculates about what might have happened if the OAS had hired a professional assassin — an Englishman, unconnected to their struggle, and free of emotion. The fascination of this story — and it is fascinating — lies in watching the English hitman (codename: the Jackal) methodically plan and prepare. He studies De Gaulle’s movements and habits, prepares false identities and an escape route, and procures and improves the perfect weapon. (You find yourself almost rooting for him.) Meanwhile, the French government’s counter-terrorist group attempts to learn the Jackal’s true identity, and to foil his plot. Not until the final pages of the story does the Jackal close in on his target… while a French policeman closes in on the Jackal. Fun fact: Forsyth would write a number of global bestsellers, including The Odessa File, The Fourth Protocol, The Dogs of War, and The Devil’s Alternative. The Day of the Jackal inspired terrorist Carlos the Jackal’s nickname.