I’d Like to Force the World to Sing

By:

July 3, 2009

How was one to explain the sudden prominence of a cohort of young conservatives (masquerading as post-partisan pragmatists) in the last few years of the Nineties? What to make of the so-called “Generation Y” we were hearing so much about at the time? I examined their writings and organizations and congressional testimony and tried to unravel their tangled ideas, but that was not enough. The editors of The Baffler asked me to come up with some kind of narrative that could make sense of it. This tongue-in-cheek conspiracy theory first appeared in The Baffler #14 (Spring 2001).

The theory starts like this: Plunged into despondency by the 1992 election, William Kristol, then chief of staff for Dan Quayle, fretted that the pot-smoking and draft-dodging Sixties were once again poised to disrupt the pleasant ersatz Fifties that he and his fellow reactionaries had built so carefully over the Reagan-Bush years. Despairing that his generation of squares would never again see the inside of the White House — which, as Joe Eszterhas has now confirmed, would shortly be transformed by Clinton and Co. into a satellite office of Rolling Stone — Kristol turned his attention to America’s youth, the demographic cohort that makes miracles possible. Unfortunately, as the theory goes, Kristol found little in the so-called “Generation X” to encourage him. As Time magazine had reported, these sullen young men and women were far too prickly and cynical even to vote, let alone vote Republican. Yet somehow Kristol had to convince these kids, schooled in the scorn of the Reagan-Bush era, to rebel against rebellion itself.

Or so, anyway, goes one of the more inventive conspiracy theories now making the rounds. The funny thing is how plausible it all seems once you start looking into it. In 1993 Kristol outlined a program for selling conservatism as rebellion in the pages of Commentary magazine, declaring absurdly that “now it is liberalism that constitutes the old order.” At the time this seemed quite mad. Today it seems prescient. We all have heard about the clear-eyed youngsters of “Generation Y,” with their faith in Wall Street and their uncanny entrepreneurial skills. Well, it’s all William Kristol’s doing. He has managed to brand an entire generation with his weird logic. But how?

Two words, according to the theory: OK Soda.

OK was “developed,” as they say in the business, by Coca-Cola marketing chief Sergio Zyman, the same man who’d developed the “brainwater” Fruitopia, at around the time that Kristol was making his appeal to youthful iconoclasm in the pages of Commentary. In 1994, OK was introduced into nine strategically selected locations, including Boston, Denver, Minneapolis/St. Paul, and of course Austin, Portland, and Seattle; it was yanked from the market only a few months later. But wait, back up: brainwater? If you’ve always wondered about the inexplicable popularity of “smart drinks” in the early Nineties, wonder no longer. Remember: it was the CIA which, by experimenting on college students in an effort to develop drugs suitable for mind control, inadvertently introduced LSD into the counterculture. In the Nineties, Kristol and his allies in the CIA simply found a way to perform the trick in reverse. In their impossible quest to conjure up a cadre of conservative youth who’d rebel against a Sixties they’d never known, Kristol and Co., the theory maintains, conspired to dose young Americans with the concentrated essence of what they called “OK-ness.”

Hold on! you object. If OK was a plot funded by the conservative establishment, and carried out with the support of the CIA and Coca-Cola, then why did the thirst quencher fail? But did OK really fail? The transcript of a 1994 National Public Radio interview with Tom Pirko, the president of a food and beverage consulting firm who’d worked closely with Coca-Cola on OK, appears significant in light of what has since transpired. Pirko told host Noah Adams that OK tastes “a little bit like going to a fountain and mixing a little bit of Coke with a little root beer and Dr. Pepper and maybe throwing in some orange.” When Adams expressed puzzlement that so vile a concoction was supposed to compete with such fruity stalwarts as Mountain Dew, Pirko boasted that “even though taste is always promoted as — as the key quality, the key ingredient of any brand, it really isn’t. It falls way down in the hierarchy. The most important thing is advertising.” (“The most important thing is advertising?” Adams asked incredulously. “No question,” confirmed Pirko.) Coca-Cola’s marketing consultant, laboring perhaps under the weight of guilt for his part in Kristol’s conspiracy, was making a confession here: OK was never intended to succeed as a soda. The whole point of the project was to inject a hip conservative worldview, as expressed by the soda’s advertising, into X’ers who’d been rendered deeply impressionable by whatever it was Kristol, et al. had put into the beverage. Once the message had been delivered, OK could vanish from the 7-Eleven has mysteriously as it had appeared in the first place.

Of what did that message consist? Recall for a moment the gloomy cloud which hung over the so-called Generation X in those days. Even the happiest organs of the mass media were admitting that X’ers were right to feel an oppressive sense of reduced opportunity, thanks to (take your pick) globalization and wage stagnation, an unchecked growth in corporate profit-taking, a glut of low-wage service jobs, pervasive undereducation, and the skyrocketing cost of college and home ownership. The young people were, as one New Yorker writer put it, “millenarian, depressed, cynical, frustrated, apathetic, hedonistic, and nihilistic.”

Coca-Cola knew this litany well. According to a 1994 article in Time, the company had been studying the behavior and attitudes of teenagers for two years before they’d introduced OK — note the timing, again — through something they called the “Global Teenager Program,” which employed graduate students from that hotbed of CIA recruitment, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Evidently concluding that global teenager programming could best be accomplished via deliberately downbeat marketing, the company proceeded to decorate OK cans with depressing art, most memorably a set of drawings of a blank-looking young man staring dolefully ahead, walking dejectedly down an empty street, and sitting outside an idle factory with his face in his hands. In the Thirties, such images might have had revolutionary connotations; in the hands of the Kristol/Coke cabal, they meant something very different. This is why the Time article, having just described the unhappy plight of Coca-Cola’s target market, continued with this telling remark: “At the same time, the OK theme attempts to play into the sense of optimism that this generation retains” (my emphasis). Dead industry and optimism? The inscrutable connection was made by Brian Lanahan, manager of — note the ominous department title — Special Projects for Coke’s marketing division, who told Time that “What we’re trying to show with those symbols is someone who is just being, and just being OK.” Translation: They were trying to produce young fogeys ready to affirm — to okay — the existing order, to look up at those silent factories and say, “Whatever.”

Enter the wily ad agency Wieden & Kennedy (Nike, Calvin Klein). Charged with the task of transmitting the message of OK-ness to a target audience who’d been chemically prepped by the foul-tasting beverage, the Portland-based Wieden & Kennedy developed a marketing campaign that seemed to pander to people’s worst fears about the mass society; it featured references to indoctrination via television, tongue-in-cheek personality tests, and, centrally, an “OK Soda Manifesto.” Copies of the manifesto are hard to come by today; I happen to have one that was printed on the back of an article I clipped from a June 1994 issue of the Minneapolis/St. Paul City Pages. I reproduce it here in full:

- What’s the point of OK? Well, what’s the point of anything?

- OK Soda emphatically rejects anything that is not OK, and fully supports anything that is.

- The better you understand something, the more OK it turns out to be.

- OK Soda says, “Don’t be fooled into thinking there has to be a reason for everything.”

- OK Soda reveals the surprising truth about people and situations.

- OK Soda does not subscribe to any religion, or endorse any political party, or do anything other than feel OK.

- There is no real secret to feeling OK.

- OK Soda may be the preferred drink of other people such as yourself.

- Never overestimate the remarkable abilities of “OK” brand soda.

- Please wake up every morning knowing that things are going to be OK.

In every particular, the “OK Soda Manifesto” exhibited those criteria which the psychologist Robert Jay Lifton identified in 1961 with the practice of “thought reform,” or mind control. As in all mind control cults, for example, the manifesto forbade OK drinkers from associating with outsiders, and restricted their vocabulary to what Lifton calls “thought-terminating clichés.” They were told how to think and warned that the individual’s own experiences could not be understood except via the group. The Reverend Jim Jones’ Kool-Aid had nothing on this stuff. As a 1995 OK promotional sticker that came bound into an issue of Might magazine put it, “OK-ness is that small thing that holds everything else together.”

Reading the “Manifesto” now one can see it as an obvious attempt to transform the then-legendary “Gen-X” disaffection into the watery contentment we associate with the (equally fictional) “Generation Y.” OK-ness, as the manifesto described it, is a doctrine designed for those who grew up in the Seventies and Eighties wondering, “What’s the point of anything?” The very things so-called X’ers found most alienating and confusing about the world were, it told them, quite OK: “War,” if you will, “is peace.” Furthermore, the OK-ness of everything was something one could only “understand” when one stopped looking for “a reason for everything”; learned to distrust the “people and situations” one had formerly looked to for guidance; and, presumably, learned to trust the forces of the market. Sound too counterintuitive? Not to worry, the “Manifesto” assured its readers: “there is no real secret” to figuring all this out, so don’t bother trying. Then the purposely vague formula for daily living: OK-ness was a movement, made up of “other people such as yourself,” and joining that movement would bring “remarkable” results. All one had to do is to “wake up every morning knowing that things are going to be OK.”

This may have seemed insipid, lame, just plain bad advertising, but it worked. Within months the media had spotted a “Generation Y” splitting off from the unhappy X cohort, a cheerful new generation for a cheerful new age. “I’m not really into that rebel thing,” proclaimed one zestful participant in a 1994 New York magazine profile of American youth. In report after report since then, journalists and analysts alike have agreed that Y’ers are much better-adjusted (read: much better employees and consumers) than gloomy X’ers ever were. “Doesn’t Smell Like Teen Spirit,” gloated the title of an article that appeared a short time ago in The Weekly Standard, a magazine that William Kristol edits. “After a decade of Gen X’ers being despondent about their prospects for fulfillment,” the story reported, “survey after survey shows teens exuberantly optimistic about their futures.” In what can only be a giddy inside joke, it then proceeded to propose as the anthem of this young, GOP-friendly cohort Jewel’s hit song “Hands,” which begins with the line — listen to it yourself — “If I could tell the world just one thing/it would be/we’re all OK.”

It may sound fantastic, but think about it. Kristol wanted the Nineties to be an inverted Sixties, in which young men would wear their hair short, young women would wear push-up bras, they’d all scorn the Sixties and love swing dancing — and in which passionate young people would add the imprimatur of their youth to the conservative campaign to discredit those concepts, and dismantle those institutions, that obstruct the progress of the free market. All of which has come to pass.

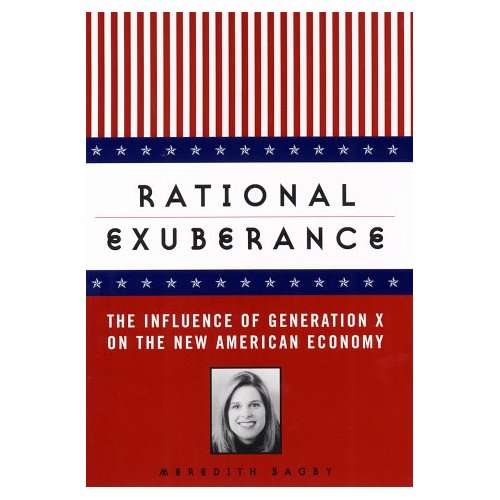

Besides, what other than mental scrambling induced by adulterated soda pop can explain the brainless gang of generational “leaders” we are evidently now fated to serve under? Behold the fruits of concentrated OK-ness: 27-year-old ideologue Mark Gerson, author of The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (1995) and editor of The Essential Neoconservative Reader (1996); 26-year-old economic writer Meredith Bagby, author of Rational Exuberance: The Influence of Generation X on the New American Economy (1998), and We’ve Got Issues: The Get Real, No B.S., Guilt-Free Guide to What Really Matters (2000); and 25-year-old “sexual counterrevolutionary” Wendy Shalit, author of A Return to Modesty: Discovering the Lost Virtue (1999). When OK was unleashed on young America, Shalit was 19, Bagby was 20, and Gerson 21. Each of them show the clear signs of repeated, heavy dosing.

As in the “OK Soda Manifesto,” Bagby’s popular book Rational Exuberance began by drawing an unexplained connection between the disaffection of young people and the doctrine of OK-ness: “Enter Generation X. With caution — and on little cat feet — wary, worn before wear, fearful, and suspicious. Still, and in seeming contradiction, we came wrapped in the passions of newness and with the relentless energy that birth always spawns.” Bagby may earn a tearful pat on the head for her maudlin “worn before wear” stuff, but she never did resolve the “seeming contradiction” of people being both fearful and optimistic at the same time. Instead, she rushed forward to define X’ers as good junior citizens, their little cat feet dutifully propelling them up the social ladder. They are “above all self-reliant and self-defining. We start our own businesses at a staggering rate. We take enormous business risks.” For Bagby the proof of her generation’s essential OK-ness was not “other-directed” goals such as world peace or social justice — although she does rant at length about Social Security “reform,” by which she means privatization — but its desire to become millionaires. Her book described a string of successful young professionals whose self-satisfied photographs bore mute testimony to Bagby’s assertion that “the ‘X’ in Generation X is the symbol for multiplication. For us the symbol strikes a chord because the most successful entrepreneurs don’t win by adding dollars — they win by multiplying dollars.”

Again and again Bagby’s work betrays the telltale mental short-circuiting that is OK Soda’s gift to American thought. Liking money, business, the market means you are a Republican, right? Nope. Bagby blithely insisted that she and her fellow brave new counter-counterculturalists were not only nonpartisan (“Neither Elephant Nor Donkey,” as the title of a chapter in her book put it) but actually postpartisan. “In 1991, when I was a college freshman,” she gloated in Rational Exuberance, “the Evil Empire whimpered its last breath. The world changed. Our ideological battle [was] won.” Everything was now to be OK forever and ever. All questions had been settled, she insisted, in one shoe-pounding sound-bite after another: “We want a government that W-O-R-K-S — that delivers the mail on time, protects the environment, fosters business, secures our future by deficit control, makes our streets safe, and stays out of our way as much as possible while doing it.” Bagby’s latest book, We’ve Got Issues, offers an even more sweeping declaration of these non-principles: “Our generation is making it where it counts,” she tells the world, “not in creed or controversy, but in shares and silicon — venture cap, options, start-ups, hedge funds, broadband, plug-ins, digital, IRAs, 401(K)s — those are our buzzwords.” And a fine set of buzzwords they were indeed — especially for William Kristol’s pals on Wall Street during that recent bout of national madness known as the Internet bubble. But beyond controversy? The cat does make one effort at leaping from the bag on its cute little feet when Bagby wonders at the book’s conclusion “whether or not I stealthily interjected some of my own prejudices (oh, of course I did) or whether I remained nonpartisan and aboveboard throughout.” Otherwise, though, Bagby is fairly consistent, insisting that free market capitalism somehow transcends politics, that she and her entire generation have been liberated from “ideology.” A more accurate description of what has befallen her and countless other tidy young strivers, according to the theory, would be a kind of political hydrolysis, a chemical conversion to a politics that otherwise made no sense.

Another victim is Mark Gerson, author of the 1996 book In the Classroom: Dispatches from an Inner-City School That Works. Gerson, too, insisted on his nonpartisanship — he just wanted things to work! But while his book ostensibly recounts a year Gerson spent as a teacher at a Catholic school in Jersey City, the plot is just there to give Gerson an opportunity to mock bilingualism, diversity training, and the idea that standardized exams may be culturally biased. Gerson’s most important contribution to the literature of young conservatism is an extended meditation on the central OK activity of sucking up to authority. He expresses shock at his inner-city students’ marked failure to suck up to him. Tongue nowhere near his cheek, he recounts that he and his suburban schoolmates were accomplished bootlickers; that sucking up was the most valuable skill he learned in school. Indeed, in his book The Neoconservative Vision, Gerson even gives readers a taste of his ability, heaping on the praise for neoconservative mentors and heroes like Gertrude Himmelfarb (“one of the world’s great social historians”), Norman Podhoretz (“a literary phenomenon”), Michael Novak (“one of the great economic philosophers of our era”), Daniel Patrick Moynihan (“perhaps the most gifted thinker to serve in public office in this century”), and Irving Kristol (“a brilliant writer of remarkable insight and great wit”). He describes a book by James Q. Wilson as “one of the best works of nonfiction in recent memory,” and his Williams College professor and mentor Jeff Weintraub as “something of a cross between an oracle and an encyclopedia.” As for William Kristol, the man who drugged and brainwashed him, Gerson describes him as “a key figure — some would say the key figure — in the transformation of the modern Republican party [into] the party of intellectual imagination and ideological excitement.” When it comes to your conservative elders, apparently, “The better you understand something, the more OK it turns out to be.”

Wendy Shalit, who went to Williams College with Gerson, became a conservative mascot in 1995 after launching a courageous journalistic crusade against co-ed bathrooms. “A Ladies’ Room of One’s Own,” her call to arms published in Commentary, was duly reprinted by that bastion of non-ideological OKness, Reader’s Digest. She’s even dated John Podhoretz, the straightforwardly conservative son of the professional ex-leftist Norman Podhoretz. Shalit’s Return to Modesty — which proposes that anorexia, date rape, and all the other “woes besetting the modern young woman” are the natural “expressions of a society which has lost its respect for female modesty” — also identifies liberal feminists as the real enemies of womankind. “It is no accident that harassment, stalking, and rape all increased when we decided to let everything hang out,” she writes. Shalit, who’s been known to defend the Promise Keepers and religious modesty laws for women, has declared that “the patriarchy, in the form of a stable structure of traditional values, and the protective authority to enforce it, is precisely what women are missing, and desperately want restored.”

Not only is it hip to be square nowadays, Shalit would have us understand, it’s hip to be brainwashed. Describing her youthful conviction that feminists “exaggerate the difficulties of being a woman” in Return to Modesty, Shalit begs the reader not to “ask me how I was so sure of this, or what this had to do with any other part of my ideology. As anyone who has ever had an ideology knows, you do not ask; you just look for confirmation for a set of beliefs. That’s what it means to have an ideology.” In other words, “Don’t be fooled into thinking there has to be a reason for everything.”

What’s So Bad About Feeling Good? asked the title of a 1968 musical comedy that tantalized Bill Kristol’s generation with a plot in which nihilistic beatniks were straightened out by a happiness virus. Today, OK-addled young people have converted the frustrated idealism of their immediate elders into a passionate complacency. The patriarchy is neat-o, Shalit insists; Gerson gives the nod to the social and economic hierarchy; and Bagby puts the seal of youthful approval on free-market capitalism. It’s like, get with the program already… OK?

NB: I wrote the following Afterword when this essay was republished in the 2003 collection Boob Jubilee, edited by Thomas Frank and Dave Mulcahey.

In the aftermath of the recent stock-market collapse, two of the fresh-faced ideologues I had profiled in my conspiracy theory quietly stepped down from their soapboxes. In 1999, Wendy Shalit had unbuckled her whalebone corset long enough to write a blistering op-ed piece about the delusional union spokespersons outraged by the vast discrepancy between the pay scales of CEOs and workers. But now that those same CEOs are taking perp walks, she’s nowhere to be found. Mark Gerson, whose butt-kissing technique had paid off a few years back, when George Gilder and others invested in his start-up market-research firm, seems to lack any further motivation to write valentines to older market triumphalists. Although they didn’t recant, at least Shalit and Gerson no longer insist that everything’s OK.

Meredith Bagby, on the other hand, still hasn’t kicked the habit. The Bagby Group, a consulting company “for businesses seeking to attract the Generation X market,” never took off — so she’s become a professional yea-sayer. A few weeks after the events of September 11, Bagby helped represent “young Americans” at a hearing of George W. Bush’s infamous Commission to Strengthen Social Security. Abasing herself before the assembled appointees, each of whom favored the privatization of Social Security, Gen X’s Most Respected Economic Writer asked that her generation be permitted to throw itself upon the actuarial grenade. “You must ask us to accept a plan that could raise our eligibility age and index it to average lifespans, lower our future benefits by altering the way they are calculated, and tax our future benefits at a higher rate,” she declaimed. “If you do this, we will not oppose you.”

I can only repeat, in conclusion: “Never misunderestimate the remarkable abilities of ‘OK’ brand soda.”

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).