“The great unknown influence on all of us [sci-fi authors of this era], which is funny because we didn’t know about it until we started talking about it, was [Bowie’s] Diamond Dogs.” — Jack Womack, 2011 interview

This page lists my favorite 75 science-fiction novels published during the cultural eras known as the Eighties (1984–1993, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema) and Nineties (1994–2003). It is a work in progress! The titles currently on this list will change, because I’m still reading.

As far as I know, science fiction’s 1984–2003 era doesn’t have a moniker already, so I’ve borrowed one from the title of one of my favorite sci-fi books of the period. This moniker is also a reference to David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs, which presciently foreshadowed the norms and forms of this material.

What characterizes Diamond Age science fiction? I’ll let you know, once I’ve had a chance to do more reading and re-reading. Off the top of my head, though, I might say: a return to pre-New Wave techno-utopianism, space opera, and kiss-kiss bang-bang action tempered and improved upon by philosophical irony and meta-textuality.

Hope this list is helpful to your own reading; let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

The following titles from science fiction’s New Wave (1964–1983) era are listed here in order to provide historical context.

- Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965)

- John Brunner’s The Sheep Look Up (1972)

- J.G. Ballard’s Crash (1973)

- Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (1974)

- Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren (1975)

- Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred (1979)

- Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (1980)

- Philip K. Dick’s VALIS (1981)

My favorite sci-fi novels of the Eighties TBD.

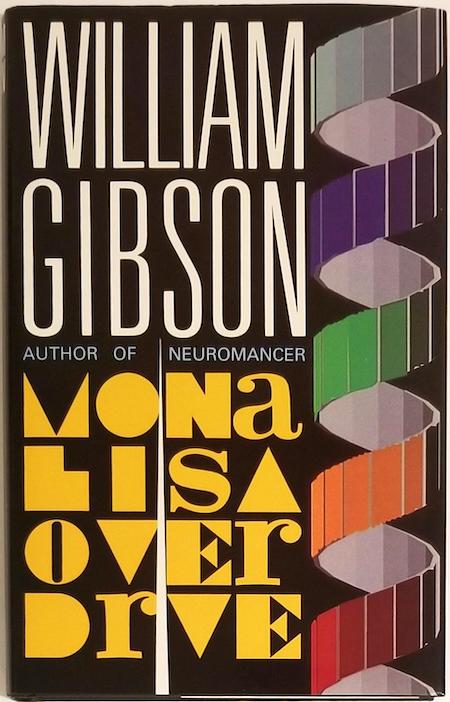

- William Gibson‘s Sprawl sci-fi adventure Neuromancer (1984). William Gibson may not have invented “cyberspace,” prototypes of which we can find in James Tiptree Jr.’s The Girl Who Was Plugged In (1973) and John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider (1975), but he coined the term; and Neuromancer — which describes cyberspace as “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts […] A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system […] Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data” — single-handedly popularized the concept. Case (a computer hacker), Molly Millions (a cyborg mercenary), and Peter (a thief and illusionist) are hired by a mysterious employer to commit a series of virtual-reality crimes that eventually lead to their assault on an orbiting data-fortress that houses two vastly powerful AIs. The plot is thrilling, but it’s the novel’s endstage-of-capitalism context — a near-future dystopian world dominated by corporations and inescapable technology, Chandler-esque noir cityscapes populated by colorful lowlifes, a virtual reality global network known as “the Matrix” — that earned it a richly deserved cult following. It’s an extraordinary debut novel, well worth revisiting. Fun fact: Neuromancer was the first novel to win the Nebula, the Philip K. Dick, and the Hugo Awards. Its sequels are Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988). Tim Miller, who made the Deadpool movie, has signed on to direct the film adaptation, currently in development.

- Octavia E. Butler’s Patternist adventure Clay’s Ark (1984). In the year 2021, a doctor named Blake and his teenage daughters are captured by Eli Doyle, the only survivor of Clay’s Ark, a spaceship that — upon its return from the first manned mission to Proxima Centauri — has crash-landed in southeastern California’s Mojave Desert. Infected with an alien microorganism that gives him heightened sensory and physical powers, but which compels him to transmit the infection to others via sexual contact, Eli has isolated himself on an isolated ranch… where he and others whom he’s captured (all of whom have been altered, by the microorganism, in ways that allow them to survive and thrive) are raising their sphinx-like offspring — intelligent quadruped mutants who perceive uninfected humans as food, and who can spread the microorganism through their bite. Society, meanwhile, has devolved into armed enclaves, marauding “car families,” and other post-apocalyptic phenomena. Blake and his daughters must decide whether to resign themselves to living within Eli’s enclave… or escape, and risk not only being captured by even worse predators, but aso creating an uncontrollable epidemic that could forever transform humankind. Though written last, Clay’s Ark is chronologically the third in the Patternist series. Fun facts: With the exception of Kindred in 1979, all of Butler’s earlier books are set in the Patternist universe. The first Patternist installment, Patternmaster, was published in 1976.

- K.W. Jeter’s sci-fi adventure Dr. Adder (1984). Jeter’s debut novel was written in 1972, the year that Pink Flamingos — John Waters’s trashy, hyperbolic, violent movie that notoriously features a live chicken being crushed between copulating weirdos — was released. Dr. Adder wasn’t published until 1984, because of the weird sex (it begins in a mutated-chicken-whore brothel managed by our protagonist, the disaffected Limmit) and hyperbolic violence, at which point it gained a cult following. It has been hailed as perhaps the first cyberpunk novel, which to me suggests that John Waters is the godfather of cyberpunk! The titular Dr. Adder is a Doctor Moreau-like surgeon who dwells in the ruins of future Los Angeles, reshaping the body parts of Orange County’s perverted teen runaways. Adder has become an unlikely symbol of freedom to LA and OC denizens, who are oppressed by the puritanism of John Mox, a financial titan and would-be ayatollah — whose daily TV sermons are opposed by the freaky ramblings of DJ KCID, a pirate-radio operator. What does the Internet-like space occupied by Mox and KCID have to do with the Interface, LA’s seediest neighborhood? Once a WMD-toting Limmit comes to town, we’ll find out. Dr. Adder is often funny, but it’s also misogynistic and disturbing. Fun fact: The character KCID is modeled after Jeter’s friend, the legendary sci-fi author Philip K. Dick. Dick contributed an Afterword to Dr. Adder, in which he claimed that had its publication not been delayed, its impact on science fiction would have been enormous.

- Bruce Sterling‘s Shaper/Mechanist sci-fi adventure Schismatrix (1985). Humankind — now dwelling in off-world colonies, around the Solar System, far from their ruined home planet — has divided into two warring schisms. Shapers evolve themselves via genetic modification and mental training, Mechanists through cyborgian upgrades; together, these factions make up the Schismatrix: extraterrestrial humanity. Our protagonist, Abelard Lindsay, is an aristocratic Mechanist who has received Shaper training; seeking to preserve Earth-bound human culture, he and his friends lead a rebellion against the Mechanists. Lindsay is exiled to a lunar colony populated by criminals, dissidents, nomads, and “wireheads” who ignore or abandon their physical bodies in favor of virtual reality; this is the most cyberpunk part of the story, which otherwise is a Foundation-like, semi-psychedelic space opera taking place over the course of nearly two centuries. When an assassin comes after Lindsay, sent by a former insurgent comrade, he is rescued by Mechanist pirates. There is much more to the plot: espionage, murder, sabotage, not to mention the arrival of the “Investors,” an alien race who are only interested in making a profit off of humankind. There is also a Robinsonade plot — of the Unalienated Work variety — in which Lindsay works for decades to develop the richest and most powerful state in the solar system. And much more — for better and worse this is a sprawling, Asimovian novel of ideas. Many ideas! Fun facts: Sterling wrote five Shaper/Mechanist stories before this novel; together, they were collected in a 1996 edition entitled Schismatrix Plus.

- Margaret Atwood‘s sci-fi adventure The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). In the not-too-distant future, perhaps 20 years from the time of the book’s writing, the United States has suffered a coup transforming an erstwhile liberal democracy into a theocratic dictatorship. Because the American population is shrinking due to a toxic environment and man-made viruses, the ability to have viable babies is at a premium. A puritanical Republic of Gilead, whose capital is Cambridge, Mass., has been established — and the regime’s elite have fertile females assigned to them as Old Testament-style “handmaids.” Drawing on historical atrocities from sumptuary laws, book burnings, the child-stealing of the Argentine generals, and the history of American polygamy, Atwood depicts a dystopia in which social control is perpetuated not only by violence but through everything from clothing to language. “Offred,” the central character, whose journal we are reading, used to be named something else; now she is “of” (belongs to) Fred, a former market researcher who has become one of the architects of the new republic; Fred’s wife, a former televangelist, is presumed barren — and bitterly resents Offred, while yearning for Offred’s child. Offred and some of her fellow handmaids attempt to reclaim their lost individualism and independence; some of this experimentalist novel’s sections describe the lives of handmaids who may or may not be Offred. Interspersed with these snapshots are Offred’s memories of her life from before and during the beginning of the revolution, including her indoctrination at the hands of government “Aunts.” The ending is ambiguous — will Offred escape? Will anyone? Fun facts: Gilead’s Secret Service is headquartered in Harvard’s Widener Library, where Atwood once researched the Salem witchcraft trials. The Handmaid’s Tale won the first Arthur C. Clarke Award; it has been adapted into a 1990 film, a graphic novel, and a much-discussed 2017–present TV show created by Bruce Miller. Atwood has announced a sequel, The Testaments, which will appear in 2019.

- Orson Scott Card’s sci-fi adventure Ender’s Game (1985). I found this book troubling, when I first read it — and that’s before I learned that the author is a right-wing homophobe. But it’s so influential that I must include it in this series! Card’s premise, that children playing videogames and laser tag in an orbiting battle school are training to fight alien invaders, seems designed to appeal to gamers whose grasp on reality is already a tenuous one. And the depiction of the protagonist, Ender Wiggin, as a genius warrior-child who has had the empathy trained out of him by adults looking for a savior is also disturbing: If you enjoy reading about kids who hospitalize and kill other kids, then this is the book for you. There’s also a sexist suggestion that females are inherently too empathetic to become true warriors; however, there are strong female characters. All of this having been said, it is thrilling to watch Ender master the tactics of his school’s antigravity war games — although it feels at times, like you’re watching somebody else play a videogame. There’s a subplot about Ender’s sister and brother, whose online screeds become incredibly influential: Again, one gets the sense that the author is pandering to Internet trolls with delusions of grandeur. The final chapter is, however, exciting — even moving. If you like Starship Troopers and The Forever War, then you’ll like this one. But don’t let your kids read it. Fun fact: Based on a 1977 story published in Analog, Ender’s Game won the Nebula and the Hugo; and its sequel, Speaker for the Dead, did as well. The novel has sold millions of copies, been translated into 25+ languages, and was voted onto both The Modern Library’s “100 Best Novels: The Reader’s List” and the American Library Association’s “100 Best Books for Teens” list. A film adaptation starring Asa Butterfield was released in 2013.

- Greg Bear’s sci-fi adventure Blood Music (1985). Transhumanism — the premise that humankind can/will evolve beyond our current physical and mental limitations — had previously been explored by sci-fi authors such as S. Fowler Wright (The Amphibians), Olaf Stapledon (Odd John), and Arthur C. Clarke (Childhood’s End); Bear was among the first to explore — in the 1983 story that was developed into this novel — the role of “wet” nanotechnology in accelerating our evolution. Ordered to destroy the “noocytes” (simple biological computers) that he’s created from his own lymphocytes, the biotechnologist Vergil Ulam instead injects them into his own bloodstream. Inside his body, the noocytes become self-aware, alter their own genetic material, form a nanoscale civilization… and begin to transform their host. What begins as a kind of horror story along the lines of David Cronenberg’s The Fly (which appeared the following year) rapidly turns into a post-apocalyptic dreamscape, as all life in the North American biosphere is infected and assimilated. There’s an amazing chapter in which a news reporter flying over America reports on the surreal scene; it’s worth noting that Bear began as a sci-fi artist. As if all of this weren’t enough, Bear trots out a pet theory that the nature of reality is affected by its observers… so the sudden introduction of billions of new intelligences throws reality out of whack. Fun facts: Originally published as a novelette in 1983 in Analog Science Fact & Fiction, winning the Nebula and Hugo Awards.

- Philip K. Dick‘s sci-fi adventure Radio Free Albemuth (1985). Unlike Dick’s many stories set in a dystopian future, this one is set in a dystopian present — one in which an opportunistic incompetent, the mouthpiece for a crackpot conspiracy theory and front-man of a right-wing populist movement, becomes president of the United States with the secret support of the KGB and the FBI. (“Why should disparate groups such as the Soviet Union and the U.S. intelligence community back the same man? … They both like figureheads who are corrupt. So they can govern from behind.”) As he wages war against “Aramchek,” an imaginary subversive organization, President Fremont abrogates American civil liberties; this leads to the emergence of a resistance movement… organized through transmissions from a superintelligent, extraterrestrial being or network known as VALIS. (See Dick’s 1981 novel VALIS.) Nicholas Brady, a record store employee, is the recipient of these transmissions, and a kind of subliminal organizer of the resistance; his experiences are a lightly fictionalized version of Dick’s own infamous “2–3–74” gnostic freak-out. As Brady becomes a successful record producer (encoding anti-Fremont messages into folk songs), his best friend, science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick, struggles in vain to stay out of the clutches of the right-wing populists. Brady’s ultimate song-message is written by a woman named Aramchek; it is recorded by a band called, yes, Alexander Hamilton. Fun facts: Drafted in 1976, published posthumously despite not being finalized. The novel was adapted by John Alan Simon in 2010; the film stars Jonathan Scarfe as Brady, Shea Whigham as Dick, and Alanis Morissette as Sylvia Aramchek.

- Ursula K. Le Guin‘s sci-fi adventure Always Coming Home (1985). A difficult but rewarding post-apocalyptic text reminiscent of Engine Summer (1979) and Riddley Walker (1980), Le Guin’s Always Coming Home isn’t exactly a novel; instead, it’s the coming-of-age story of a young Kesh woman, Stone Telling, interleaved with a Silmarillion-esque ethnological account of the cultural facts, legends, poetry and song of the Kesh people. The Kesh are a peaceful community who inhabit an isolated island in what used to be California’s Napa Valley; at some point in the distant past, they seceded from the rest of America in order to cultivate a mindful approach to technology use, ecological systems, and everything else. An Internet-like computer system survives whatever catastrophe befell America; so does solar power, California’s Route 29 (“the old straight road”), steam engines, modern medicine, and flotsam and jetsam like styrofoam. As with the social order depicted in the author’s The Dispossessed (1974), Kesh society is an ambiguous utopia: Stone Telling rebels against the culture’s taboo against scientific and technological progress. Although she recognizes the flaws of the patriarchal, hierarchical, militaristic neighboring society in which she spent some years growing up, she is attracted to some aspects of that culture. Fun facts: Le Guin’s parents were noted anthropologists who studied the native peoples of Alta California; this book — early editions of which included a cassette tape of Kesh music — is a tribute to their life’s work. It is also, according to one character,”a mere dream dreamed in a bad time, an Up Yours to the people who ride snowmobiles, make nuclear weapons, and run prison camps by a middle-aged housewife, a critique of civilization possible only to the civilized, an affirmation pretending to be a rejection, a glass of milk for the soul ulcered by acid rain, a piece of pacifist jeanjacquerie, and a cannibal dance among the savages in the ungodly garden of the farthest West.”

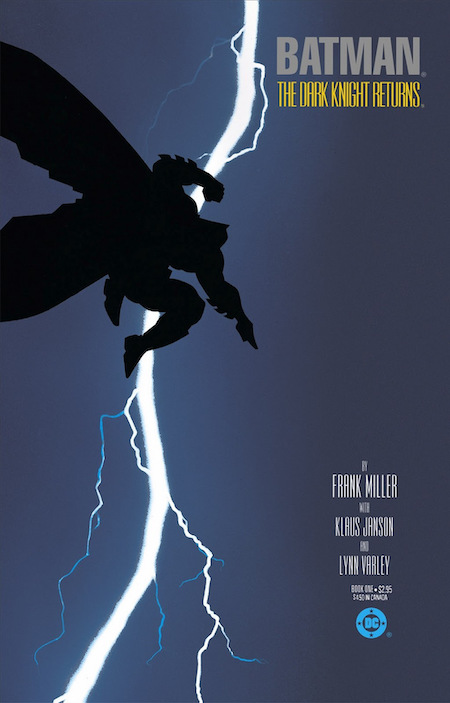

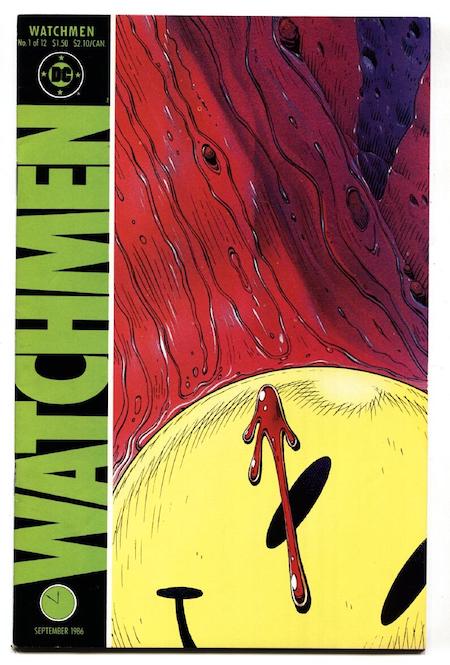

- Frank Miller‘s graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns (serialized 1986; illustrated by Miller and Klaus Janson, colored by Lynn Varley). Batman first appeared, in 1939, as a grim avenger who punishes evildoers whom the law can’t touch; at the acme of the hardboiled Thirties (1934–1943), Batman was the hardboiled-est. However, once the Comics Code Authority was established, in 1954, Batman comics became whimsical, wacky, family-friendly even. Then DC’s Dick Giordano hired writer-artist Frank Miller — who’d transformed Marvel’s Daredevil and Wolverine into darker, more popular characters — to create The Dark Knight Returns. Inspired by the Clint Eastwood-directed Sudden Impact, in which Dirty Harry, now in his 50s and forced into semi-retirement, returns to work as a quasi-vigilante, the right-wing Miller reimagined Bruce Wayne as the antithesis of “truth, justice, and the American Way” Superman. In a dystopian, yet present-day Gotham City, a retired Wayne returns to action to stop, first, Two-Face, and second, a hyper-violent street gang known as the Mutants. He’s joined by Carrie Kelley, a young woman he’d rescued, who becomes the new Robin. The police issue an arrest warrant for Batman; worse, the Joker frames Batman for murder! When Batman mobilizes the disbanded Mutants as vigilantes on the side of justice, the US government orders Superman to apprehend him. Fun fact: First published as a four-part miniseries, The Dark Knight Returns, has been hailed as one of the greatest works in the comics medium. Its popularity, along with Watchmen, published by DC in 1986–1987, kicked off the era known as the Dark Age of Comic Books.

- William Gibson‘s Sprawl sci-fi adventure Count Zero (1986). Several years after the events of Gibson’s debut novel, Neuromancer, Bobby Newmark, a small-time computer hacker who calls himself “Count Zero,” uses an unknown piece of software to infiltrate a closely guarded data defense network. Bobby is rescued from certain death by an angelic being (who turns out to be the young daughter of Christopher Mitchell, a brilliant researcher and bio-hacker); and after a brutal mugging, he is taken in by a group fascinated by what appear to be voodoo gods suddenly proliferating in the Matrix — the synergistic linked computer database that encompasses all information on Earth. Meanwhile, Turner, a corporate mercenary soldier, gets caught up in a violent battle for control — by the multinational corporations Maas Biolabs and Hosaka — over Mitchell’s biochip technology, which is superior to silicon microprocessors. (We’ll discover that Mitchell was led to develop the biochip by the “voodoo gods” of the Matrix; which reminds me of Philip K. Dick’s Radio Free Albemuth.) Turner ends up on the run with Mitchell’s daughter, who carries with her the “biosoft” secret… which not only Maas Biolabs and Hosaka, but an immortality-seeking multibillionaire will stop at nothing to secure. The final showdown, between the various forces at odds in this collaged, meta-textual, action-packed novel, takes place in the Sprawl, a Judge Dredd-like urban environment that extends along much of America’s East coast. Fun facts: Count Zero was serialized by Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in 1986, and published in book form the same year. The third and final installment in the Sprawl triology is Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988).

- Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s graphic novel Watchmen (serialized 1986–1987). In an alternate-history version of the present day, nearly all freelance costumed vigilantes have been outlawed; so the superheroes who’d emerged from the 1940s through the 1960s are now dead or retired. However, when Edward Blake, a right-wing, gun-toting Vietnam vet and paramilitary agent, is murdered, one of his former comrades — the ruthless crime-fighter Rorschach, who is the only remaining active masked vigilante — begins an investigation. Against a backdrop of impending nuclear war between the US and the USSR, Rorshach’s efforts bring Nite Owl, Rorschach’s former crime-fighting partner, and Silk Spectre. Though flashbacks, we learn the sometimes sordid history of the Minutemen, a 1940s superhero group whose number included Captain Metropolis, the original Silk Spectre, Hooded Justice, the original Nite Owl, Silhouette, Dollar Bill, Mothman, and The Comedian; and we learn about the origin of Dr. Manhattan, the only truly superhuman character in the story — whose godlike powers, and ability to perceive time in a non-linear fashion, causes him to grow increasingly detached from human affairs. Slowly it becomes evident that the former hero known as Ozymandias (Adrian Veidt), known as “the smartest man on the planet,” is up to something that may change the course of history… but for better or worse? Moore and Gibbons rely heavily on synchronicity, coincidence, and repeated imagery to create an atmosphere of paranoia, nostalgia, and cosmic awe… and it’s also a thrilling mystery. Wow. Fun facts: Moore’s original idea for Watchmen used superhero characters that DC had acquired from Charlton Comics: the two Nite Owl characters were based on two versions of Blue Beetle; Silk Spectre was inspired partially by Nightshade, one of the earliest female superheroes; Ozymandias was inspired by Peter Cannon (aka Thunderbolt), who’d attained “the highest degree of mental and physical perfection”; and Rorschach was based on the Question, a ruthless, faceless character developed by Steve Ditko. Watchmen, which has been called one of the best and most influential graphic novels of all time, was adapted as an OK 2009 Zack Snyder movie. The 2019 Watchmen TV show, created by Damon Lindelof, is pretty great so far.

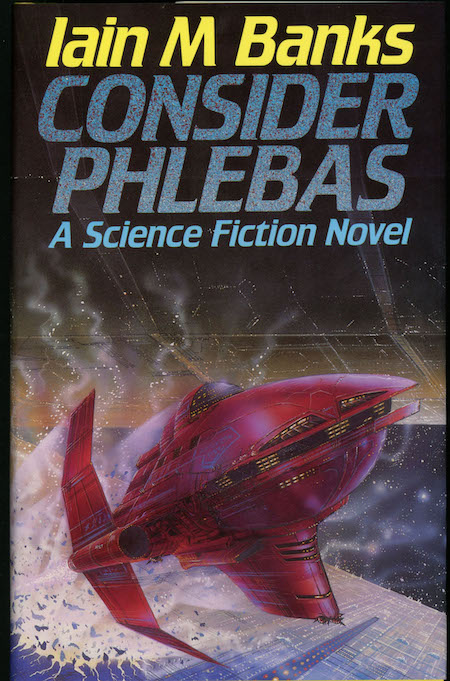

- Iain M. Banks‘s Culture sci-fi adventure Consider Phlebas (1987). When Banks set about rebooting sci-fi’s Space Opera genre, he invented the Culture — a post-scarcity, galaxy-spanning, left-libertarian society of humanoids, aliens, and godlike “Minds” (artificial intelligences) dwelling primarily in spaceships and other off-planet constructs. Although self-sufficient, the Culture derives its sense of purpose from improving the lives of those in developing societies. Sounds utopian, right? However, Bora Horza Gobuchul, protagonist of the first Culture novel, is an honorable, principled shape-shifter who despises the Culture for its decadence. There’s a war going on between the Idiran Empire (a three-legged, religious, warrior race) and the Culture; Horza — whom we first meet in a prison cell slowly filling with sewage — is an agent of the unpleasant Iridans. His mission? Capture a damaged Culture Mind (which was intended for use on a new class of warship) that’s stranded on an off-limits, post-catastrophic planet. Banks is perhaps having too much fun with the genre, in his first effort: there’s a prison break; Horza joins a crew of pirates and is taken prisoner by a cannibal cult; the Culture destroys one of its own mega-colonies; and there’s a dizzying array of future tech. It’s also perhaps a bit too long-winded, a bit too much telling vs. showing, at times. But it’s a very impressive effort, and Perosteck Balveda is the first of many interestingly conflicted Culture agents that we’ll encounter. Fun fact: Nebula-winning sci-fi author (and HILOBROW friend) Charlie Jane Anders has recounted, of Consider Phlebas, that the book “made me start reading science fiction in general, after a lapse, and made me want to write in the genre myself.” Amazon announced in 2018 that it has acquired the TV rights to Consider Phlebas, which will be adapted by Dennis Kelly.

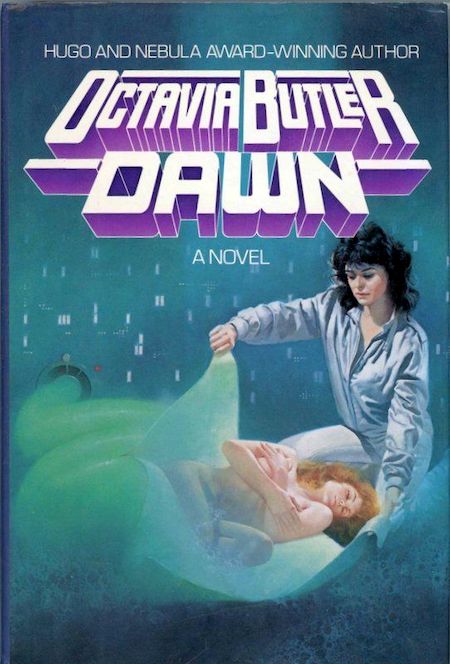

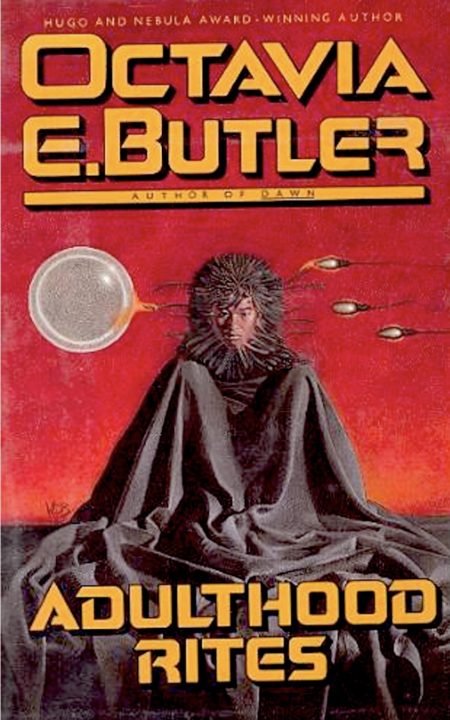

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Xenogenesis sci-fi adventure Dawn (1987). The first installment in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy (also known, collectively, as Lilith’s Brood) begins with the reawakening of Lilith Iyapo, a young black woman who was abducted from a post-apocalyptic Earth by an alien race, the Oankali… 250 years ago. The Oankali, who possess the ability to interbreed with any humanoid species, travel the galaxy doing so; they manipulate the genes of their offspring as needed to allow these new species to thrive in particular environments. The nearly extinct humankind has obviously failed, they inform Lilith… so why doesn’t she help them oversee a program of breeding little tentacled Oankali/human babies? Lilith is caught between a rock and a hard place: her fellow human survivors have a tendency to be xenophobic, violent, and misogynistic; while the Oankali are peaceful and reasonable… yet they view humans as an inferior species, without inherent rights. If it sounds to you as though Butler is exploring themes of sexuality, gender, race, and species in a nuanced, complex fashion, you’re right; she’s also recapitulating not only the story of African slaves in America, but the story of their descendants’ struggle, as well. Lilith is a strong character, yet within the context of Oankali imperialism, she lacks agency. Like Butler’s other black female characters, she refuses to capitulate to either/or choices. Fun fact: The sequels to Dawn are Adulthood Rites (1988) and Imago (1989). In 2017, it was announced that Ava DuVernay will adapt Dawn for television, with director Victoria Mahoney and producer Charles D. King. This will be the first on-screen adaptation of Butler’s writing.

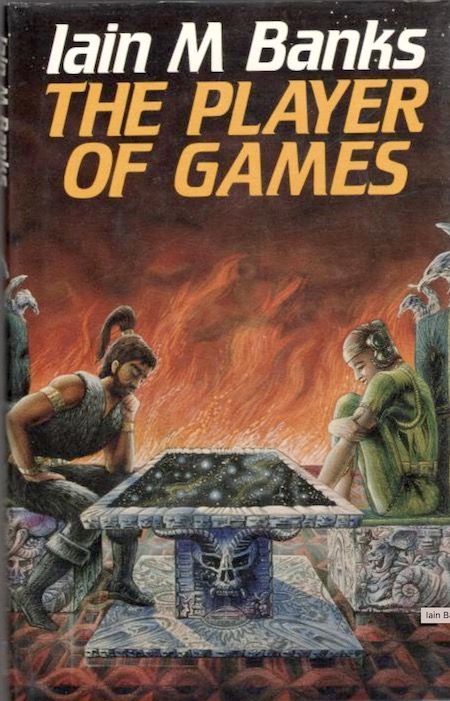

- Iain M. Banks‘s Culture adventure The Player of Games (1988). The Glass Bead Game in space? Games, for those lucky enough to belong to the technologically advanced and leisurely Culture, are considered one of humankind’s highest achievements and most worthwhile pursuits; within that context, Jernau Morat Gurgeh is one of the best players of games. Gurgeh, a brilliant, blasé, and not particularly likeable character, is recruited by Special Circumstances — an outfit that does the Culture’s dirty work when it comes to interacting with less-developed galactic civilizations — and tasked with participating in a ritual gaming tournament the outcome of which will determine the players’ social status… and who the Azad Empire’s next emperor will be. (The Azad Empire, BTW, is America: materialistic, exploitative, sexist and racist, pasty and bloated.) Meanwhile, what’s up with the AI drone Mawhrin-Skel, who has been ejected from Special Circumstances? Although we never learn every aspect of “Azad,” an immersive virtual reality game, we get the impression that it’s highly complex and demanding; there are three-dimensional game boards of various shapes and sizes, various numbers of players who can compete or cooperate, and randomness is a factor. Gurgeh discovers that the Azad game is a crucial vehicle for transmitting the Azad Empire’s values to its population… and it’s for this reason that the Culture wants to interfere. As he advances through the tournament, Gurgeh is matched against increasingly powerful Azad politicians, and finally the Emperor himself; will Gurgeh survive the tournament? And even if he does, will the experience infect him with Azadian non-Culture values? Fun facts: The second published Culture novel. A film version was planned by Pathé in the 1990s, but was abandoned. In 2015, Elon Musk named two SpaceX autonomous spaceport drone ships — Just Read the Instructions and Of Course I Still Love You — after AI ships in this book.

- William Gibson‘s Sprawl science fiction adventure Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988). Eight years after the events of 1986’s Count Zero: Kumiko, the adolescent daughter of a Yakuza boss, hides out in London with “Sally Shears” (Molly Millions, the knife-fingered mercenary from 1984’s Neuromancer), not to mention a biosoft apparatus that presents as a British child (and which can only be seen by Kumiko); Angie Mitchell (from Count Zero) struggles in the aftermath of a breakdown caused by her Simstim fame, and seeks her missing boyfriend; Mona, an amateur teen prostitute pimped by her nasty boyfriend, is caught up in a crime organization’s attempt to abduct her celebrity lookalike; and the comatose body of Bobby Newmark (the titular protagonist of Count Zero) is cared for by Slick Henry, a Mark Pauline-esque junkyard-dwelling giant-robot artist and car thief who suffers from blackouts. Molly and Angie are the motivating forces, here: they’re looking to force a confrontation and settle the turmoil unleashed by the events of the previous books. Bobby, meanwhile, has become addicted to an Aleph, a Borgesian super-capacity cyber-harddrive that is, essentially, a self-contained world. Will Angie regain the ability to access cyberspace directly, via the biosofts implanted in her head by her father? What is Continuity — the AI that is the most important decision-maker for Sense/Net, Angie’s production company — up to? Will Bobby wake up? Fun facts: Steven Poole wrote in The Guardian that “Neuromancer and the two novels which followed, Count Zero and the gorgeously titled Mona Lisa Overdrive, made up a fertile holy trinity, a sort of Chrome Koran (the name of one of Gibson’s future rock bands) of ideas inviting endless reworkings.”

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Xenogenesis adventure Adulthood Rites (1988). Thirty years after the events of Dawn (1987), the population of Earth is divided into communities of Oankali (a seemingly benign, tentacled alien species that travels through the universe seeking partner species with whom to “trade” their own genes) and their half-human, half-Oankali offspring, and sterilized human resisters. Akin, the half-Oankali son of Lilith Iyapo, ambivalent protagonist of Dawn, is raised by five parents representing three genders — the Oankali “third sex” is known as the ooloi — and two species. Captured by human resisters, because (for the moment) he looks fully human, Akin finds them as horrifying and as compelling as his mother found the Oankali; for the first time, he finds value in his human side, and learns the value of preserving human culture. (Progressive types are often counseled to try to understand Make America Great Again types, and in large part that is the theme of this book.) Later, Akin becomes an emissary traveling back and forth between Oankali/hybrid and resister villages — and advocates for the resisters to have their fertility restored and to be sent to a terraformed Mars to form their own civilization. But will humankind always self-destruct, if left to their own devices? And will the resisters continue to accept Akin’s assistance once he begins to metamorphose into an adult? Fun fact: This is the second installment in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy; it is followed by Imago (1989). Nominated for the Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel.

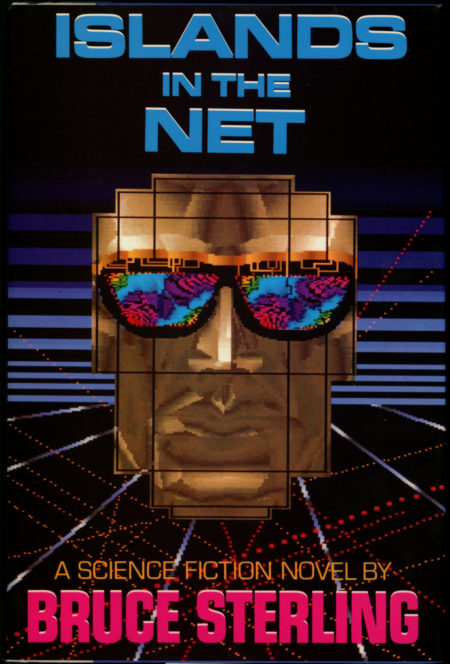

- Bruce Sterling‘s Islands in the Net (1988). In the near future — the 2020s (!) — economic and political life is dominated by democratized multinational corporations, and everyday life is shaped and misshaped by Net-enabled instantaneous worldwide communications. Yes, this is a cyberpunk novel… but our protagonist, far from being a rebellious young (usually male) hacker, is a married, middle-aged career woman. Laura Webster works for the multinational megaconglomerate Rizome, which stores its data in Granada, Luxemburg, and Singapore; these data havens, however, have been linked to anticapitalist terrorist activity. Laura, her architect husband, and their baby embark on a global tour to restore Rizome’s damaged reputation. When one data haven representative is assassinated (via an armed drone), the story turns into a hunted-man adventure; Laura and her family find themselves hiding out among offshore scientists and artists, the Church of Isis, and agents of rival multinationals. Sticky Thompson, a face-changing terrorist with neurotoxin bacteria in his gut, and Jonathan Gresham, a rogue American journalist involved in a low-tech Tuareg nomad rebellion, are compelling characters. Sterling did a good job predicting wearable tech: Net-connected glasses and watches; and his Net is more like the one we experience today than the semi-hallucinatory, cyberspace version conjured up by William Gibson. Fun facts: “I don’t think any SF prognosis can hold up in sharp detail,” Sterling said in a 2000 interview. “But I would bet that if you took a broad list of near-future 1980s science fiction novels and looked at them in the 2020s, Islands in the Net would seem far less ludicrous than most.” Agreed.

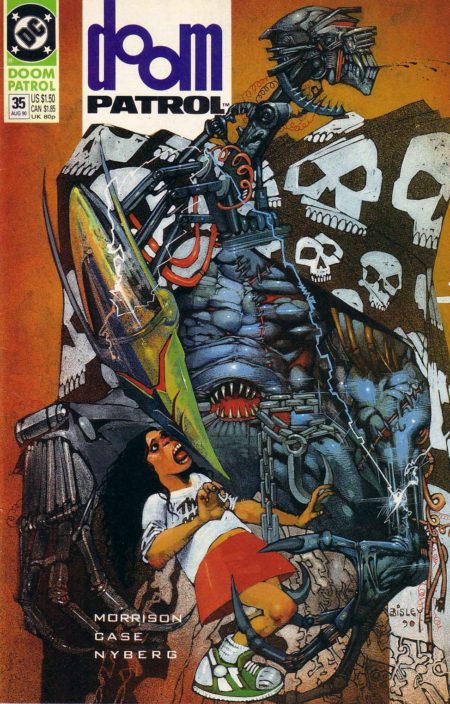

- Grant Morrison and Richard Case’s Doom Patrol comic (1989–1993). “Le Poète est semblable au prince des nuées/Qui hante la tempête et se rit de l’archer,” laments Baudelaire, in “L’Albatros.” “Exilé sur le sol au milieu des huées,/Ses ailes de géant l’empêchent de marcher.” The Doom Patrol, as the superhero team first appeared in DC’s My Greatest Adventure #80 (June 1963), could relate. The Chief, a wealthy, paraplegic, brilliant scientist-inventor; Robotman, a former daredevil and race-car driver turned cyborg; Elasti-Girl, a former athlete and actress who can expand or shrink her body at will; and Negative Man, a former test pilot who can release a negatively charged energy being from his body — they perceive their so-called gifts as a curse, dooming them to a life of alienation. Scottish comic book writer Grant Morrison, part of the far-out British Invasion of American comics that included as Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman, took over the relaunched Doom Patrol series in 1989; DC stopped submitting the title to the CCA for approval around that time. The resulting run — from issues 19 through 63 — was wild. The Chief (whom, we will later discover, may have had something nefarious to do with the origin stories of his comrades) leads Robotman (a brain, remember, trapped in a body without nerves), Rebis (a queer, transgender, transracial entity combining Negative Man, his energy spirit, and Eleanor Poole, a black doctor), Crazy Jane (a victim of sexual abuse; each of her 64 alternate personalities has a different super-power), and a monkey-ish psychic named Dorothy against the Scissormen — metatextual, Struwwelpeter-like inquisitors who worship a god that exists at the crossroads where realities meet, and whose cut-up dialogue reads like Dada poetry. Ultimately, the Doom Patrol’s weirdness proves to be the key to its effectiveness: They often team up with so-called villains in order to combat the neo-fascist, Foucauldian forces that police sexual identity and gender norms. Richard Case’s trippy artwork is simultaneously engaging and nightmare-inducing. Fun facts: The last line of Morrison’s run quotes the Smiths’ “Asleep”: “There is another world/There is a better world/Well, there must be….” It’s a beautiful statement of revolutionary optimism for an era that had largely abandoned utopian idealism.

- Masamune Shirow’s seinen manga series 攻殻機動隊 (Mobile Armored Riot Police; in the US: Ghost in the Shell (1989–1990). Public Security Section 9 is a counter-cybercrime organization, in mid-21st-century New Port City, Japan — led by Major Motoko Kusanagi — a synthetic “full-body prosthesis” augmented-cybernetic human. Thanks to her wetware (a computer user interface implant located in her cranium’s suboccipital nerve region), Kusanagi’s mind can seamlessly interact with mobile devices, machines, and networks; although her brain is a century old, her prosthetic body is one of the most advanced models on the market. So she’s not only the best hacker on her team, which is composed of former police and military types, she’s also the toughest; also, because the comic was published by the laddish Japanese manga anthology Weekly Young Magazine, Kusanagi is a slapstick, sexy character (think Tank Girl) fascinated by “human” vices. Villains include the Puppeteer, who has mastered the art of “ghost hacking” people’s cyberbrains and forcing them to commit crimes by proxy (and who turns out to be something much worse than a mere crook); as well as neo-noir corrupt officials and sinister corporate types. Shirow’s dynamic black and white drawings are simultaneously silly and hardboiled, detailed and gestural; the comic is too grown-up for kids, too child-like for grownups — perfect! Fun facts: Manga artist-author Masanori Ota’s pen name is derived from the legendary sword-smith Masamune. Ghost in the Shell was released in tankōbon (stand-alone) form in 1991; in 1995, Dark Horse serialized the series in English. The 2017 movie adaptation was criticized because it cast Scarlett Johansson in the lead role; also, Evan Narcisse of io9 lamented that the movie version of Kusanagi asks the wrong sort of existential questions about herself.

- Dan Simmons’s Hyperion Cantos adventure Hyperion (1989). Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales is a collection of stories — told by a disparate group of pilgrims — within a frame story, the overall effect of which is to paint a sardonic portrait of 14th-century English society. This 29th-century Chaucerian space opera gives us a priest, a soldier, a poet, a scholar, and other pilgrims chosen by the Shrike Church and the Hegemony of Man (which rules some 200 human-inhabited planets) to make a request of the so-called Shrike, a deadly half-mechanical, half-organic creature that can control the flow of time. As they progress in their journey, away from their home planets (simulacra of ancient Earth societies and cultures) towards the remote, titular planet Hyperion, where the mysterious Shrike dwells, we learn — via the pilgrims’ stories — that the Ousters, a faction of humanity mutated by centuries of living in deep space, plans to invade Hyperion… and that Hyperion’s enormous, provocatively empty Time Tombs are about to finally reveal their secrets. Earth has reportedly been destroyed; the Hegemony’s technology (strikingly, readily available teleportation devices) comes from a secretive civilization of self-aware AIs, who inhabit a cyberspace-esque realm that is divided into warring factions. There’s a legend suggesting that all but one of a group of pilgrims to the Shrike will be horribly killed, and the other granted one wish; why has this group of individuals been selected for this mission? It’s a metatextual novel: The astute reader will pick up allusions to everything from Shakespeare to The Long Goodbye and The Wizard of Oz, and of course to other sci-fi novels. And it’s a literary work, too: Each novella mashes up genres, from the detective story and horror to action-packed combat, even romance. Phew! Fun facts: Winner of the Hugo and Locus Awards. The next book in the series was The Fall of Hyperion, published in 1990.

- Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love (1989). The Binewskis are in the traveling circus business; to that end, father and mother have used amphetamines, arsenic, and radioisotopes on their unborn children… purposely breeding a one-family freak show. Arturo, who has flippers for limbs, is known as Aquaboy; Iphigenia and Electra are conjoined twins; and Olympia, the book’s narrator, is an albino hunchback. Only Chick, the youngest, appears unremarkable. There are two story lines, here. One, a picaresque set in the past, follows the family from town to town as the kids get older. Arty, a megalomaniac, founds a cult (“Arturism”) devoted to the pursuit of “Peace, Isolation, Purity” by means of limb-amputation; his one-man freak show threatens the Binewskis’ livelihood, which leads to strife. The other story, set in the present, is an Imitation of Life-esque melodrama about Oly’s daughter, Miranda, who was abandoned as an infant. Miranda has fallen into the clutches of a deranged wealthy woman who wants the teenager to undergo cosmetic surgery, to make her look “normal.” And then there’s the saga of Chick, whose telekinetic power is terrifying. Fun facts: This book was a big deal, among some of us, when it appeared; it predicted the carnivalesque atmosphere of 1990s-era youth culture. And Dunn, a terrific writer unlike any other, came out of nowhere. Even the cover art — designed by Chip Kidd — was ahead of its time, eschewing “good” typography and illustration for… something weird, “lame.” Tim Burton aquired the film rights, at one point; the Wachowskis — cool, confident freaks who could have been Binewskis — were also interested.

- Octavia E. Butler‘s adventure Imago (1989). In the final installment in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy, the future of not only Earth’s surviving humans but their alien captors/saviors, the tentacled Oankali, is at stake; can Jodahs, a half-human, half-Oankali ooloi (a genderless figure, who makes satisfying sexual relations between men and women — whether Oankali, modified human, or hybrid — possible) mature successfully into its adult form? Concerned that our protagonist will inadvertently contaminate them before it learns to control its genetic manipulation abilities, the Oankali send Jodahs to live in the woods. Here, we finally discover that the seemingly unemotional, almost clinical alien invaders need and long for (emotionally, sexually) relationships with humans. In fact, Oankali and modified humans alike can’t stand to touch members of the opposite sex without the mediation of an ooloi; and this mediation becomes addictive, for Jodahs, who experiences its exile as torment. Jodahs is also tortured by its inability to fit into any group — so when it encounters two human siblings, Jesusa and Tomas, it forms a new family unit. The book is erotic without being explicit, and despite one’s horror/revulsion at this post/evolved-human state of affairs, we care enough about the characters and their struggles to root for everything to work out. Will Earth’s humans, in the end, be as accepting of the Oankali as we are? Fun facts: As in the first two Xenogenesis books (1987’s Dawn and 1988’s Adulthood Rites), Butler asks us to grapple with unsettling issues of consent, coercion, and enslavement. Some readers find this book too philosophical; others think it’s the best of the trilogy.

- Lois McMaster Bujold’s Vorkosigan Saga adventure The Vor Game (1990). The sixth installment in the Vorkosigan Saga (1986–ongoing) is a fun one. Miles Vorkosigan, the protagonist of most of the series, is the brilliant, driven scion of an aristocratic family from the feudalistic, swords’n’spaceships planet of Barrayar; he is disadvantaged in his abitions because his mother is a Betan (she hails from a technology-rich, egalitarian galactic society), and because he is a dwarf. In a previous series installment, The Warrior’s Apprentice (1986), Miles manages to get himself accepted into the Barrayaran Imperial Military Service, after a brief career as “Admiral Naismith,” the swashbuckling leader of a mercenary space fleet. Here, shortly after graduating from the academy, Miles is assigned to a winter infantry training post, where he runs afoul of the tyrannical base commander. Charged with mutiny, he is recruited to work for Barrayaran Covert Ops, and winds up in a prison cell with Barrayar’s young emperor, Gregor, who had sneaked away from his palace. Worse, a Cetagandan invasion fleet — Cetaganda has staged several unsuccessful wars against Barrayar, in previous Vorkosigan books — may be en route towards the space station where they’re imprisoned. In order to repel the attack, Miles must outwit a femme fatale (herself a mercenary leader), his former commanding officer, and reconnect with his mercenary friends. Fun facts: Bujold has stated that the Vorkosigan Saga’s structure is modeled after the Horatio Hornblower books. The first several chapters of The Vor Game were originally published in a slightly different form as “The Weatherman” in the February 1990 issue of Analog. The Vor Game won the 1991 Hugo Award for Best Novel.

- Iain M. Banks‘s Culture adventure Use of Weapons (1990). There are two narratives in this, the third Culture novel. In one, which moves forward in time, we follow Special Circumstances agents Diziet Sma, a female human, and Skaffen-Amtiskaw, a snarky AI drone, as they recruit ex-agent Cheradenine Zakalwe, a rogue, assassin, military genius, and sad sack, to further the aims of the Culture — nudging benighted galactic civilizations away from political tyranny, economic plutocracy, and cultural ignorance and intolerance, and towards enlightenment, left-libertarianism, and peace — in a politically unstable star system. (The drone believes that Zakalwe is burned-out; it can’t even guess at his real problem.) These are three of Banks’s best characters, and it’s fun to watch them in action; Zakalwe is the titular used weapon — the Culture needs him to do things that it regards as reprehensible. There is plenty of action as Zakalwe heroically achieves the Culture’s goals. The second narrative, meanwhile, moves chronologically in reverse! Here, we learn about earlier jobs that the near-sociopathic Zakalwe has performed for Special Circumstances, and eventually we learn about his childhood — growing up in a non-Culture social order, and commanding an army in a bloody civil war. Zakalwe has demanded that his Culture handlers locate a woman named Livueta; when he finally reunites with her, there’s a major plot twist that helps us to understand his motivation. As with every Culture novel, we’re left grappling with political-science conundrums. Fun facts: Diziet Sma and Skaffen-Amtiskaw also appear in Banks’s story “The State of the Art”; and we’ll meet Zakalwe again, too, under a different name. One hears that Banks wrote an even more complex version of this story in 1974, but abandoned it; years later, fellow Scottish sci-fi author Ken MacLeod — also known for chronologically tricksy story telling — helped him figure out how to transform it into something publishable.

- William Gibson and Bruce Sterling‘s The Difference Engine (1990). If Adorno and Horkheimer had, instead of writing The Dialectic of Enlightenment, collaborated on an alternate-history novel about how things might have looked differently, in Victorian-era Britain, had Charles Babbage (the mathematician and inventor who in real life never completed his “difference engine” — a mechanical computer designed to produce error-free tables of mathematical functions commonly used by engineers and scientists — achieved his vision, the result might have looked something like this. By 1855 the Tory Party and hereditary peerage have been eclipsed by Babbage’s Industrial Radical Party, which champions the acceleration of technological change and social upheaval. Mechanical computers are now ubiquitous, though electricity is still just a theory; all sorts of steam-powered technologies have flourished. There’s a big downside: A proto-Orwellian surveillance state has come into being. Against this rich backdrop — too rich, perhaps; the book is in part a collage of material lifted from Victorian journalism and pulp fiction, and it’s crammed with historical jokes — we follow three stories, linked by a mysterious set of powerful computer punch cards. Sybil Gerard, a political courtesan, wants revenge for the execution of her Luddite father; Edward Mallory, a dinosaur expert, chances into possession of the cards, and must dodge secret agents in a London on the brink of anarchy; Laurence Oliphant, a real-life explorer and British spy, plays a smaller but provocative role. The book doesn’t have a conventional resolution; instead, Ada Lovelace, the real-world mathematician who published the first algorithm intended to be carried out by Babbage’s mechanical computer, thus inventing computer programming, explains the cards’ significance in a lecture about open systems. Also, we finally realize just who has been narrating this wild history. Fun facts: The Difference Engine, which the authors wrote by swapping a floppy disk back and forth, was not the first steampunk novel, but it is perhaps the most influential early example of the genre. Eileen Gunn’s online Difference Dictionary is a helpful resource, when reading this book.

- Karen Joy Fowler’s Sarah Canary (1991). Is Sarah Canary a sci-fi novel? It was nominated for Nebula Award, so sci-fi readers certainly think it is. A weird-looking, white-skinned woman — wearing a battered but fashionable black dress — wanders into a railway camp in Steilacoom, Washington in 1873; she warbles like a canary instead of speaking. Railway worker Chin Ah Kin is ordered to take “Sarah Canary,” as she’s dubbed, to a nearby asylum; he ends up in the asylum, himself. There, the two meet B.J., an inmate who is sporadically sane. The three of them escape and head for San Francisco. The traveling party comes to include a showman named Harold, and Adelaide, a suffragette who fears the conventional roles of women; both seek to exploit Sarah for their own purposes. What follows is a funny, moving, sometimes terrifying series of adventures and misadventures. The reader may suspect that this is a first-contact novel; Sarah indeed seems to possess unearthly abilities, or maybe unearthly technology. However, if our titular character is indeed a visiting extraterrestrial, then this picaresque makes it clear that the year 1873 was a particularly unfortunate time for a tour of the misogynist, racist American West — which Fowler renders as strange and terrifying as any alien planet. Fun fact: Fowler is best known as the author of The Jane Austen Book Club, a best-selling novel that was made into a 2007 romantic movie of the same name. But she began her career as a writer publishing sci-fi stories; Sarah Canary was her first novel. In 1991, Fowler cofounded the James Tiptree, Jr. Award, a literary prize for science fiction or fantasy that “expands or explores our understanding of gender.”

- John Barnes’s Century Next Door adventure Orbital Resonance (1991). In the far future, after Earth’s ecology has been all but destroyed, a generation of children is being raised on the Flying Dutchman, a colony built on an asteroid looping between Earth and Mars. Melpomene Murray, our 13-year-old protagonist, and her cohort have been trained — and, as Melpomene comes to realize, mentally conditioned — from birth, to lead mankind into the future. “Lead” might be the wrong word, however, since Melpomene’s handlers, in their wisdom, have organized an adolescent social order in which young people won’t and can’t function on their own, outside of their highly cooperative groups. Unlike the kids in Ender’s Game, that is to say, these young folks aren’t hyper-competitive geniuses; instead, they seek consensus, rely entirely on one another, and prioritize the group’s success over their own individual success. Even their sports games, like the variable-gravity, lacrosse-style activity called Aerocrosse, involves working together. The worst insult, in these kids’ vocabulary, is “unco” — which stands for “uncooperative”. So is this a utopia or a dystopia? Mel and her friends thoroughly enjoy their lives… until they’re joined by a boy from Earth who has grown up with different values. The story ends abruptly, as series installments sometimes do, but it’s a fun, provocative slice of life in the spirit of Heinlein’s juveniles — though it’s not actually written for a young audience. Fun fact: Nominated for the Nebula Award. The following three books in the Century Next Door series are Kaleidoscope Century (1995), Candle (2000), The Sky So Big and Black (2002).

- Pat Cadigan’s Synners (1991). Gina, Visual Mark, and Gabe are middle-aged virtual-reality creatives, who’ve seen new technological breakthroughs transform their industry — and the wider world — for better and worse. The brain has been thoroughly mapped; and “sockets,” which allow us to input sensory information directly into our brains, and which were at first intended for entertainment purposes (immersive movies and music videos), have changed the way people experience life. When the corporation for which they work (Diversification Inc.) gives Visual Mark sockets, he becomes even less tethered to reality than before. Gina isn’t particularly interested in sockets — but she uses them to stay connected with her ex-boyfriend. It seems that these virtual-reality creatives can use sockets not only to input experiences, but to output them too; Visual Mark feels liberated by the technology, and abandons his body. Gabe, meanwhile, who was a bit of a slacker, finds it hard to adjust to sockets — which demand that he focus his attention and be the ever-present master of his imaginings. Instead of mastering this new technology, our three protagonists are mastered by it. Like one of Gabe’s productions, the novel itself is a bit cryptic, and hard to follow, with multiple POVs… until suddenly, after the halfway point, it coheres into a powerful, thrilling adventure story. Fun facts: Robert A. Heinlein dedicated his 1982 novel Friday to Cadigan. She won a Hugo Award for her 2012 novella The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi.

- Neal Stephenson‘s Snow Crash (1992). Snow Crash, Stephenson’s first sci-fi novel, was developed from elements of a Ghost in the Shell-esque graphic novel that he’d abandoned; as such, it’s visionary yet goofy, deep yet two-dimensional, thrilling yet rambling and tedious, stylish yet stupid — which is fun. It’s set not only in a cyberpunk-influenced, ambiguous-libertarian-utopian future Los Angeles, but also in the “Metaverse,” a virtual reality-based successor to the Internet — the users of which interact as “avatars” (a term this book didn’t coin but popularized), with one another as well as with software agents. But if you’re expecting William Gibson’s spare, neo-noir prose, you’ll be disappointed; Stephenson is a maximalist — diving down every open rabbit-hole. Prose limitations aside, it’s a terrific thrill-ride. The quick-thinking, skateboard-riding courier Y.T. (for “Yours Truly”) is an impressive female hero; Hiro Protagonist, the half-black, half-Japanese hacker who teams up with her has awesome skills… though he’s not the protagonist. Within the Metaverse, Hiro is offered a datafile named Snow Crash — the term refers to a particular software failure mode on early Apple Macs; hackers who view the file (a virus, a drug, a religion — what’s the difference?) suffer not only catastrophic computer problems but brain damage. A massive infodump informs us that cultural information comes in discreet self-replicating packets, which can be transmitted like a virus or genetic code; and that the Sumerian language is the firmware programming language for the human brainstem, which supposedly functions as the BIOS for the brain itself. (In Stephenson’s recounting of the story of the Tower of Babel, the goddess Asherah personifies a linguistic virus created to control all humankind; the god Enki created a counter-program that caused humans to speak other languages.) Raven, the story’s villain, is terrifying and oddly sympathetic; Uncle Enzo, the Mafia kingpin who takes a paternal interest in Y.T., is also a compelling figure. There is plenty of action, here, even if the climactic action sequence is somewhat of a letdown. Fun facts: Snow Crash’s Metaverse has influenced the development of everything from Second Life to the videogame Quake. In 2017, Amazon announced that it was co-producing an hour-long sci-fi TV show based on Snow Crash; Joe Cornish is executive producer.

- Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy adventure Red Mars (1992). This is the first installment in a trilogy — with Green Mars (1993) and Blue Mars (1996) — that collectively won the Nebula Award, and the Hugo and Locus Awards twice. The story explores egalitarian, sociological, and scientific advances made on Mars, while retrograde Earth suffers from overpopulation and ecological disaster. Red Mars is set (at first) in what was then the not-too-distant future of the 2020s; a group of 100 American and Russian colonists — including John Boone, Maya Toitavna, Frank Chalmers, and Arkady Bogdanov — are leading a terraforming mission on Mars, the red planet. Robinson writes “hard” sci-fi, so we get a lot of info about domes made of piezoelectric plastic, genetic experimentation, giant satellite mirrors reflecting light to the surface of the planet, and Symmes Hole-like “moholes” drilled to create planetary vents of hot gases. (None of this literally world-building tech is particularly woo-woo; it’s all reasonable.) At the same time, this is an epic tale about a grand social experimentation — and, at an individual level, it’s a story of romance, rivalries, friendships, ambition. Red Mars has its adventurous aspects, but somehow the most adventure-like moments — interminable treks across barren wastes — are the least engaging. More fun is watching the “First Hundred” split into factions: they don’t leave behind their old national, social class, religious, and cultural identities and worldviews, nor their neuroses and bad habits; and they can’t (ever) agree on the best way to help humankind flourish. Things fall apart: Characters of whom we’ve become fond are killed, systems we’ve watched form are shattered. Earth, meanwhile, falls under the control of transnational corporations that come to dominate its governments — who show an increasing interest in meddling in Martian affairs! Fun facts: Red Mars has been described as an exemplar of Mundane Science Fiction (MSF). In a 2005 interview I conducted with Fredric Jameson, he suggested that KSR’s Mars Trilogy offers the best example of post-Cold War utopianism, because instead of asking the reader to decide on any one of the colonists’ competing ideologies, the author “goes back and forth between these various visions, [allowing us to see] it’s not a matter of choosing between them but of using them to destabilize our own existence, our own social life at present.”

- Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang (1992). The titular China Mountain Zhang is a gay New Yorker of Chinese descent; unambitious, introverted, and concerned to hide the truth about his national origin (American-born-Chinese are considered inferior to Chinese-born-Chinese; also, he’s half-Hispanic), Zhang isn’t the heroic type. Instead, he serves as our guide to a future world in which America’s economy has collapsed and the People’s Republic of China has become a hegemonic world power. In the chapters about Zhang, he begins as a construction foreman; his sexuality has cost him his first job and his chance of a great career in Shanghai. He’s posted to an Arctic scientific station on Baffin Island, as an engineering tech; he studies cutting-edge, daoist engineering in Wuxi, the new Imperial City; he tutors Martian homesteaders in their hard-scrabble agricultural commune; and he finishes up as a kind of super-architect. Along the way, he cruises for casual sex, while taking care to mask his same-sex desire — whih is forbidden, in China. The book’s other chapters show us the world from the perspectve of other characters: San-xiang, a deformed Chinese woman who seeks genetic modification, only to discover that a pretty face isn’t the solution to her problems; Angel, a cyber-kite flier in New York; two Martian settlers. There are many stories, here; they don’t cohere — but they all concern ordinary people winning small-scale victories within a repressive social order. It’s not an adventure, but it’s impossible to put down. Fun fact: McHugh’s first novel, China Mountain Zhang was nominated for the Hugo and Nebula Awards, and won the James Tiptree, Jr. Award. It has been described as an exemplar of “Mundane Science Fiction” (MSF). McHugh’s 2011 collection, After The Apocalypse, was one of Publisher’s Weekly‘s 10 best books of 2011.

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Earthseed adventure Parable of the Sower (1993). Lauren Olamina, a teenager living in a gated community outside of Los Angeles, suffers from hyper-empathy; she viscerally feels whatever physical pain she witnesses. However, in the not-too-distant future (the 2020s), when the social order begins to collapse due to global warming, economic stagnation, racism and sexism, and extreme wealth disparity, Lauren’s condition may prove to be a super-power, of sorts. If she can survive, and find people she can trust — then Lauren’s prophetic “seeds” — her ideas for a new social order, one based on a religion that will teach self-sufficiency and a radically new understanding of what God is — may have a chance of finding purchase. The story, told through (rather stoic, matter-of-fact) journal entries, details the brutal events that come to pass during the early days of America’s collapse, as well as Lauren’s efforts to found a utopian “Earthseed” commune in northern California. Now that it’s nearly 2020, Butler’s depiction of what’s to come — including a president who aims to make America great again by suspending minimum wage, environmental, and worker protection laws — feels depressingly, chillingly accurate. Fun facts: The first in a two-book series. The book’s title is borrowed from a parble that Jesus tells (in Matthew 13:1-23, Mark 4:1-20, and Luke 8:4-15) about a sower whose seed falls on various patches of ground, most — but not all — of which are inhospitable.

- Jeff Noon’s Vurt adventure Vurt (1993). In the anarchic, rain-swept environs of future Manchester, England, nearly everyone is obsessed with “Vurt” — a vast multiplayer virtual reality game/consensual hallucination accessed by sucking on drug-infused colored feathers. (Also: dog-human hybrids have formed a thriving subculture, with their own rock stars; flesh cops and shadowcops pursue those who access illicit versions of vurt; and there’s and there’s a tentacled, multi-orificed, harmless Thing From Outer Space, too.) Vurt, it seems, is in fact a kind of parallel world, or multiverse; you can lose things there, and bring other things back. This is the situation haunting our narrator, Scribble, who’s lost his sister — with whom he is sexually obsessed — somewhere in the game. As he careens around with his friends, the chrismatic but largely unsympathetic Stash Riders, in search of exotic and illicit vurt feathers, Scribble schemes to retrieve Desdemona, somehow, from wherever she may be. (There’s an echo, here, of the Tammuz/Ishtar myth.) In the end, Scribble may have to give up everything he knows and loves in order to succeed in his quest. For better and worse, this is a story very much of its moment: “In science fiction, once a generation there are one or two voices that capture the times the same as bands do,” says Warren Ellis. “In 1993, post-rave, where things were still jumping but they were starting to get a bit dark… Jeff Noon was the sound of post-rave.” Fun fact: Winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award. Noon’s second book, a sequel, is titled Pollen (1995); he also wrote a prequel, Nymphomation (1997). In 2017, Ravendesk Games published a tabletop role-playing game version of Vurt.

- William Gibson‘s Bridge adventure Virtual Light (1993). A bike messenger who lives in the Bay Bridge community — an anarchic shantytown suspended between San Francisco and Oakland; it’s divided into suspension-side and cantilever-side zones — steals a valuable pair of sunglasses, which (it turns out) allow the wearer to perceive optically encoded information about a ruthless corporate cabal’s scheme to raze San Francisco and rebuild it using nanotechnology. The first installment in Gibson’s Bridge trilogy is set in the then-near future of 2006; although the context of Virtual Light is post-catastrophic (earthquake, social upheavals), this series is not nearly as far-out as his Sprawl trilogy. Alas, it’s more realistic: the middle class has all but vanished, public space has been privatized, everything is polluted. The messenger, whose name we eventually discover is Chevette, takes it on the lam. She is pursued by two cops (Svobodov and Orlovsky), a psychotic assassin (Loveless) dispatched by the company that made the glasses, and by Rydell — a former police officer hired by the “skip-tracer” Lucius Warbaby. (Meanwhile, another subplot focuses on Yamazaki, a Japanese sociologist studying the bridge dwellers — in particular, Chevette’s mentor, Skinner.) When Rydell catches up with Chevette, he has to decide whether to take her in… or to join her in attempting to get the word out about the nanotech plot! Fun facts: The novel was a finalist nominee for a Hugo Award.

- Jack Womack’s Dryco adventure Random Acts of Senseless Violence (1993). In near-future New York, 12-year-old Lola Hart must contend with political and civil unrest (riots, fires, disease outbreaks, roaming gangs), as well as the effects of increasing inflation. When her formerly well-to-do family is forced to move to Harlem, she loses touch with her private-school friends and takes up instead with three streetwise African American girls: Iz, Jude, and Weezie. This prequel to Womack’s six-book Dryco series is the Mad Max of the series; in this installment, things rapidly go from screwed-up to abysmal. The military struggles to control what remains of the American state; a sinister corporation called Dryco assumes possession of what were formerly public-sector goods; and an increasingly ignorant and desperate populace worships “E” — a bygone rock’n’roller turned godling. In just a few months, the United States descends into violent anarchy; rape and murder are everyday facts of life, for Lola and her scrappy crew. Lola’s diary, which we’re reading, and whose vocabulary and idioms change dramatically from beginning to end (“Everything downcame today, the world’s spinning out and I spec we finally all going to be riding raw”), suggests that such violence is systemic… and by no means random. Fun facts: The Dryco series begins with — in order of publication — Ambient (1987), Terraplane (1988), Heathern (1990), and Elvissey (1993). An adult version of Lola’s character appears briefly, and violently, in Ambient. Cory Doctorow and others have called Random Acts of Senseless Violence Womack’s under-appreciated masterpiece; when asked why he thought the book hadn’t succeeded, Womack blamed its terrible cover art.

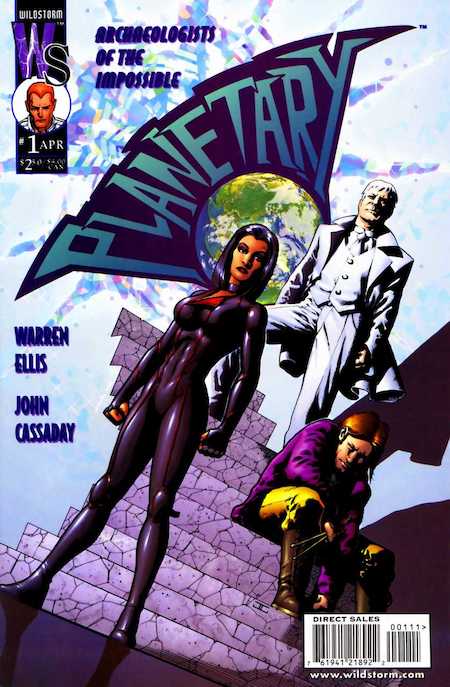

In a 1999 introduction to a collected edition of Warren Ellis and John Cassaday’s comic Planetary, Alan Moore had the following to say:

Comic book creators moving through this wasteland between centuries [i.e., when “the massive scaffolding of values where the comics field was raised seems now deserted, seems redundant”] are, it would seem, subject to twin, conflicting impulses. On one hand is the reckless New-Year’s-resolution urge to plunge headlong into the future, as of course we must, while on the other hand we have the weighty knowledge of the glittering rubble that we leave behind us, at our backs. With so much of great worth there in the long backyard of comics history, we are obliged to ask ourselves if there might not yet be buried treasures, items fit for salvage. Many of us seem to have the feeling, only mistily defined, that it is some element in comics past that will provide the key with which we can unlock the medium’s future. As if in order to move forward, we must also somehow simultaneously move back, however paradoxical that may appear.

My favorite sci-fi novels of the Nineties TBD.

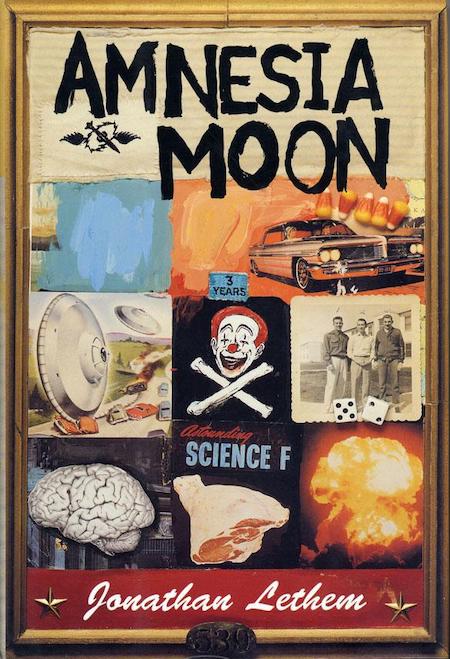

- Jonathan Lethem’s sci-fi/neo-noir adventure Gun, with Occasional Music (1994). The author’s first novel is a pastiche of hardboiled crime fiction and cyberpunk; it’s affectionate towards the former, tongue-in-cheek towards the latter. In a not-too-distant future Los Angeles and Oakland, smart-mouthed private “inquisitor” Conrad Metcalf looks into the murder of Dr. Maynard Stanhunt, a prominent urologist who turns out to have been in cahoots with the gangster Danny Phoneblum. The victim’s ex-wife and the murder suspect’s sister are raising a “babyhead” — one of a cohort of infants whose development has been sped up, resulting in a Gen X-like subculture of cynical, unmotivated, whiny assholes. A thuggish evolved kangaroo (think Wilmer, the jumped-up “gunsel” from The Maltese Falcon) is tailing Metcalf, who’s got the hots for a sexy inquisitor with the unimprovable name Catherine Teleprompter. All these shenanigans take place in a dystopian America in which it’s all but forbidden to use words to describe news events; there’s a cultural taboo against asking questions; and everyone is on [the] Make, a legal drug that keeps users forgetful and contented. The inquisitors, who’ve settled upon a fall guy for the murder rap, subtract so many of Metcalf’s state-issued karma points that he may wind up doing time in the big freeze. But when Metcalf uncovers a scheme in which zero-karma convicts are implanted with “slaveboxes” and used as prostitutes (hello, Dollhouse), he plays it “existential. and maybe a bit stupid.” It’s the only way he knows how to play it. Fun fact: “I really, genuinely wanted to be published in shabby pocket-sized editions and be neglected — and then discovered and vindicated when I was fifty,” Lethem has said, about his early novels. “To honor, by doing so, Charles Willeford and Philip K. Dick and Patricia Highsmith and Thomas Disch, these exiles within their own culture. I felt that was the only honorable path.”

- Iain M. Banks‘s Feersum Endjinn (1994). Too many fans of Banks’s Culture series pooh-pooh this, his second non-Culture story — complaining in particular about the Riddley Walker-esque patois in which the character Bascule the Teller speaks. True, it’s not as fun as the Culture books… but like them it’s a staggering work of imagination, and a lot of fun. This one takes place in a vast, Gormenghastian castle-like structure known as the Fastness, around which the novel’s protagonists clamber like ants (one thinks of Aldiss’s Non-Stop), and also in the Cryptosphere, a vast dataspace that can be explored virtually, via avatar, and to which millions of personalities have been uploaded — but which is succumbing to entropy and chaos. Sessine, an assassinated military commander who wakes up in the Cryptosphere, only to be assassinated there, too; in this post-singularity future, we discover, a person can die several times, not only in the real world but virtually. We also encounter a top-ranked scientist, Hortis Gadfium, who is conspiring against the King; she is privy to new intel about an approaching catastrophe known as the Encroachment. Asura, a Leeloo-like figure, is tasked with activating the titular “fearsome engine” that will save the solar system… but she has amnesia; captured, she is subjected to a series of virtual-environment storytelling effort to learn her secret. Meanwhile, Bascule, a Teller (whose job it is to project himself into the Cryptosphere in search of lost information), gets caught up in the political machinations and seeks refuge among chimeric animals. The final chase scene — involving a vacuum balloon ascending a space elevator — is terrific. And honestly, Bascule isn’t that hard to understand! Fun facts: “I used to have these model soldiers, and I wondered what it would be like to be one of those tiny soldiers in a giant house,” Banks would later explain in an interview. “I used to have these epic journeys for them. I thought if you had a giant structure, basing it on furniture would be easy.”

- Nancy Farmer’s children’s cyberpunk adventure The Ear, the Eye and the Arm (1994). In the year 2194, Africa is the world’s dominant continent. Zimbabwe, a rising African power, plays host to communities including the African Shona and Xhosa tribes, and the English and Portuguese tribes — which are segregated not so much by race as by wealth and culture. While Chief of Security General Matsika leads the country’s fight against the Masks, a criminal gang, his three children sneak out of their fortified mansion in Harare, to explore the bustling marketplace of Mbare Musika. Kidnapped, Tendai, Rita, and Kuda undergo a series of unfortunate events — from being forced to mine reusable plastic from a massive dump, to an unpleasant stay in Resthaven, an independent country within Zimbabwe that aims to retain traditional African culture, to a climactic encounter with the Big-Head Mask in the Masks’ mile-high-skyscraper secret lair. (Because this is a children’s book, we never get the sense that they’re actually in mortal danger, except perhaps for the final scene.) Meanwhile, the children are sought by the titular detectives, a bumbling, argumentative, multicultural trio of mutants, each of whom possesses a unique ability: the Ear has super-sensitive hearing, the Eye has hawk-like vision, and the Arm is an empath. Critics at the time admired the fact that Farmer, a white author, normalized the characters’ Zimbabwean perspective, and honored the culture’s myths and religious beliefs. Fun facts: Farmer enlisted in the Peace Corps, and subsequently worked in Mozambique and Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe), where from 1975–1978 she studied biological methods of controlling the tsetse fly. The Ear, the Eye and the Arm was a Newbery Honor Book, an ALA Notable Book, and an ALA Best Book for Young Adults.

- Charles Burns‘s horror/sci-fi graphic novel Black Hole (serialized 1995–2005; in book form, 2005). I became aware of Charles Burns in the mid-1980s, thanks to his retro-sci-fi/horror “El Borbah” and “Big Baby” stories, which at the level of form may have paid tribute to the stylings of Will Elder, Hergé, and Chester Gould — but which were more sophisticated, in a surrealist, absurdist way. I was 28 when Kitchen Sink (Fantagraphics took over, later) began publishing the twelve installments that would make up Black Hole; I was 38 by the time the complete version was published. I mention this because my take on the story changed, during those years. A sexually transmitted disease mutates teenagers — over the course of a summer, in a suburb of Seattle, in the mid-1970s — into B-movie-esque monsters! The lucky ones are those who merely grow a little tail, or sprout chest-tendrils, or who shed their skin! Within this milieu, a lover’s triangle develops among Chris, Rob, and Keith; Keith, meanwhile, falls under the erotic spell of Eliza, a free-spirited artist living with dope dealers! Chris runs away, to live in the woods near her fellow freaks; but someone is killing them! When early issues of Black Hole appeared, I reveled in what I understood to be Burns’s nihilistic, body-horror take on, say, Dazed and Confused. However, by the time the last installment appeared, I looked forward not to finding out what happened next (for better or worse, it’s essentially a midcentury-style romance comic) so much as reimmersing myself in Burns’s fully realized world — gorgeous chiaroscuro, discontinuous chronology, teenage angst, sexual frustration and liberation… plus David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs. Wow! Fun facts: “There are certain truths that exist in genre fiction, even though it’s full of stereotypes and two-dimensional characters,” Burns said in an interview, once. “There’s a certain amount of unconsciousness that goes into genre fiction or genre movies. And out of that unconsciousness, I always see a certain kind of truth.”

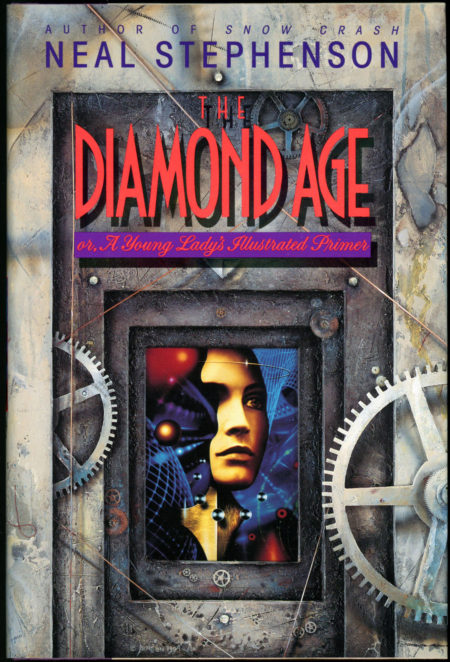

- Neal Stephenson‘s The Diamond Age: Or, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer (1995). When the designer of the Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer: a Propædeutic Enchiridion — an interactive story-telling device intended to inculcate in the granddaughter of “Equity Lord” Alexander Chung-Sik Finkle-McGraw the knowledge and skills to subvert the dominant paradigm — bootlegs a copy for his own daughter, it instead falls into the hands of young Nell, a bright 4-year-old slum-dweller. Under the tutelage of the Primer, Nell not only survives but thrives. Lord Finkle-McGraw, meanwhile, attempts to exploit Hackworth to advance the goals of his tribe; so does Dr. X, the Chinese engineer (and powerful Confucian leader) who’d helped Hackworth create the illicit Primer. Meanwhile, the actress Miranda, who provides the voice of the Primer and becomes a kind of surrogate mother to Nell, seeks the child out. All of this takes place against the backdrop of a Neo-Victorian British colonial society in which nanotechnology has made it possible for anyone to 3-D print food and objects, and government has become obsolete. The relationship between Nell and her Primer is an affecting one; in a sense, this is a book is a bildungsroman about homo superior — like Stapledon’s Last Men in London or Odd John, say, or Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder. However, in the book’s second half, the plot goes off the rails — with the introduction of tribes such as the Drummers, who create a subconscious hive mind through sexual orgies (is this a reference to Alan Moore’s Halo Jones comic?); the powerful CryptNet organization; and the Chinese Fists of Righteous Harmony. Stephenson’s goal is to explore the unintended consequences of a post-scarcity world… but the story ends abruptly and inconclusively. Fun fact: An enchiridion is a handbook; a propædeutic is a preliminary teaching, for beginners. Other fun fictional propædeutic enchiridions include Owen Hughes’s Arithmetic, Grammar, Botany & these Pleasing Sciences made Familiar to the Capacities of Youth, in Joan Aiken’s The Whispering Mountain (1968); and Huey, Dewey and Louie’s Junior Woodchucks’ Guidebook, from Carl Barks’s Donald Duck comics; the Junior Woodchucks first appear in 1951. PS: When my friends Elizabeth Foy Larsen and Tony Leone and I pitched the family activity book UNBORED to Bloomsbury, in 2010, we explicitly compared it to Stephenson’s Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer.