Tyger! Tyger!

By:

April 16, 2010

The comic book artist, writer, and editor Jack Kirby (a HiLo Hero) was a giant of both Golden Age (1934-63) and New Wave (1964-83) science fiction. Without diminishing the man’s contributions to science fiction and comics, I’d like to point out that — like all Golden-Age and New Wave sci-fi authors, no matter how talented or original — Kirby was heavily influenced by Radium Age (1904-33) science fiction and fantasy. A piece of art upon which I recently stumbled offers incontrovertible evidence of this!

But first, some background…

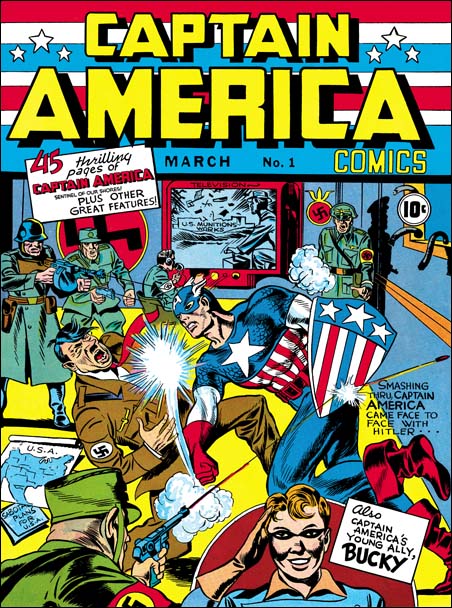

In 1938, at age 21, Kirby got his start drawing science fiction comics — e.g., the strip, The Diary of Dr. Hayward, in Wild Boy Magazine. In the early ’40s, working for the publisher that would become Marvel Comics, he drew superhero comics like The Blue Beetle and co-created Captain America. Superhero comics are a subgenre of science fiction; as I’ve noted before, the superhuman meme first appeared in the late 19th century. However, it was refined into a recognizable subgenre of science fiction by Radium Age science fiction tales like J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder, Olaf Stapledon’s Sirius, John Taine’s Seeds of Life, Erle Cox’s Out of the Silence, Philip Wylie’s Gladiator, Edmond Hamilton’s “The Man Who Evolved,” and George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah.

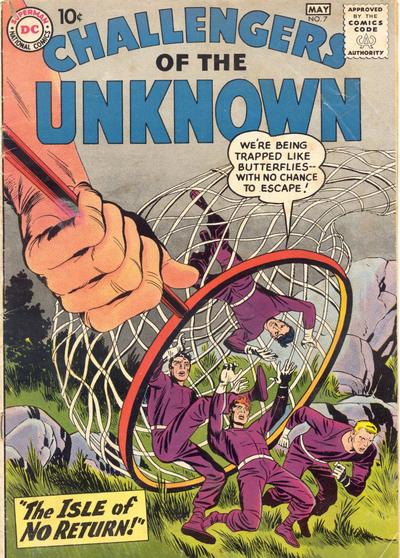

In the late 1950s, Kirby helped create DC’s Challengers of the Unknown (1958-59), he drew a newspaper comic strip called Sky Masters of the Space Force; he also pushed DC’s Green Arrow comic in a sci-fi direction. Challengers of the Unknown and Sky Masters of the Space Force are examples of the “space opera” subgenre of science fiction. Like the superhuman meme, the space opera meme first appeared in the 19th century: e.g., Star ou Psi de Cassiopée: Histoire Merveilleuse de l’un des Mondes de l’Espace (1854) by C. I. Defontenay, and Lumen (1872) by Camille Flammarion; George Griffith and Robert Cromie are later 19th-century pioneers. The space opera meme was refined into a recognizable subgenre of science fiction by Radium Age authors like Garrett P. Serviss, Ray Cummings, Edmond Hamilton, J. Schlossel, and — crucially — E. E. “Doc” Smith.

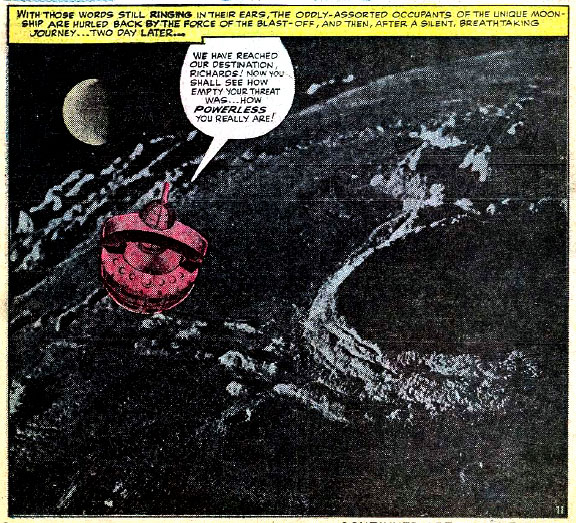

In ’58, at age 41, Kirby returned to Marvel (then called Atlas Comics) and drew some of the greatest sci-fi comics stories ever: e.g., “I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers” (Strange Worlds #1, December 1958); and innumerable sci-fi stories for Marvel’s Amazing Adventures, Journey into Mystery, Strange Tales, Strange Worlds, Tales to Astonish, Tales of Suspense, and World of Fantasy. Near the end of science fiction’s Golden Age (in what, confusingly, is known as Marvel’s Silver Age), Kirby and Stan Lee co-created trail-blazing sci-fi superhero comics like The Incredible Hulk (1962) and Iron Man (1963); as well as three Argonaut Folly sci-fi superhero series: The Fantastic Four (1961), The Avengers (1963), and The X-Men (1963). Olaf Stapledon’s 1935 novel, Odd John, about an international band of teenage and twentysomething “supernormals,” is perhaps the first sci-fi Argonaut Folly; its publication date situates it on the cusp between the Radium Age and the Golden Age of science fiction, though Stapledon is a Radium Age author.

GOLDEN-AGE SCI-FI at HILOBROW: Golden Age Sci-Fi: 75 Best Novels of 1934–1963 | Robert Heinlein | Karel Capek | William Burroughs | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Clifford D. Simak | H.P. Lovecraft | Olaf Stapledon | Philip K. Dick | Jack Williamson | George Orwell | Boris Vian | Bernard Wolfe | J.G. Ballard | Jorge Luis Borges |Poul Anderson | Walter M. Miller, Jr. | Murray Leinster | Kurt Vonnegut | Stanislaw Lem | Alfred Bester | Isaac Asimov | Ray Bradbury | Madeleine L’Engle | Arthur C. Clarke | PLUS: Jack Kirby’s Golden Age and New Wave science fiction comics.

Having helped pioneer the comic-book version of Golden Age science fiction, in the mid-1960s Kirby helped pioneer the comic-book version of New Wave science fiction. New Wave SF is characterized by an ambitious, self-consciously artistic sensibility; in fiction, the movement took off in 1964, when Michael Moorcock took over the editorship of the British science fiction magazine New Worlds. New Wave science fiction was less interested in outer space than in the nature of perception, mass media, entropy, and politics. Precisely at this moment, Kirby’s Marvel comics began to blow minds with their experimentations in form and content; and — once he moved back to DC — he explored perception, mass media, entropy, and politics in his writings.

Kirby’s proto-psychedelic photomontages were first seen in ’64, which helps demonstrate my theory that the Sixties began that year; and his proto-psychedelic energy fields, known to fans as the “Kirby Krackle,” were first seen in ’66. He also co-scripted and drew the Argonaut Folly superhero comic series The Inhumans (1965). If The Avengers (1963), and The X-Men are examples of work on the cusp between the comic-book science fiction’s Golden Age and New Wave eras, The Inhumans is New Wave. Again, many themes from The Inhumans are anticipated by Stapledon’s Odd John.

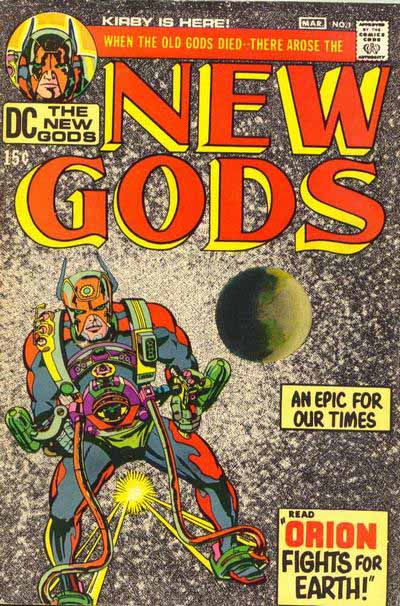

In the early 1970s, the New Wave movement in science fiction literature peaked; by 1983, Cyberpunk was the dominant paradigm. In 1970, Kirby returned to DC and began to crank out a series of weird, interwoven New Wave science-fiction titles — including The New Gods (1971), Mister Miracle (1971), and The Forever People (1971) — under the blanket sobriquet “The Fourth World.” In the Fourth World comics, which were cancelled in ’73, Kirby’s heroes were young outsiders who championed human freedom; his villains were powerful tyrants determined to colonize not outer space, but inner-space; that is, to negate freedom entirely. (Forever People No. 5: “If someone possesses absolute control over you — you’re not really alive!”) We find precisely the same themes in Radium Age science fiction classics like Stapledon’s Last Men in London, Karel Čapek’s R.U.R., Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

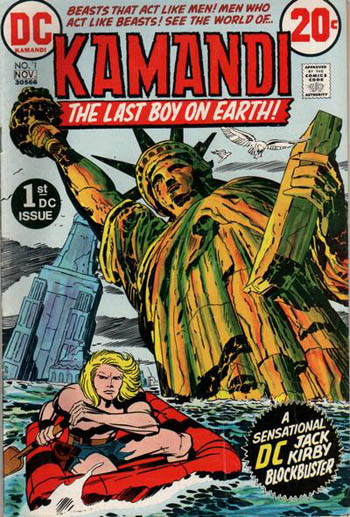

One of Kirby’s final New Wave science-fiction series was DC’s Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth (1972), each issue of which explored perception, mass media, entropy, and politics. Kamandi is a teenage boy on a post-apocalyptic Earth that has been ravaged by the Great Disaster. As I’ve written before, apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction is another meme that appeared in the 19th century, and was refined into a recognizable subgenre of science fiction by Radium Age science fiction and fantasy tales. These include: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer’s When Worlds Collide, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Moon Men, Karel Čapek’s The Absolute at Large, M.P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud, Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (1913), William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men.

NEW WAVE SCI-FI at HILOBROW: 75 Best New Wave (1964–1983) Sci-Fi Novels | Back to Utopia: Fredric Jameson’s theorizing about New Wave sci-fi | Douglas Adams | Poul Anderson | J.G. Ballard | John Brunner | William Burroughs | Octavia E. Butler | Samuel R. Delany | Philip K. Dick | Frank Herbert | Ursula K. Le Guin | Barry N. Malzberg | Moebius (Jean Giraud) | Michael Moorcock | Alan Moore | Gary Panter | Walker Percy | Thomas Pynchon | Joanna Russ | James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon) | Kurt Vonnegut | PLUS: Jack Kirby’s Golden Age and New Wave science fiction comics.

Which brings us to the incontrovertible evidence of Radium Age science fiction and fantasy’s influence on Jack Kirby. Just in case you’re still not convinced by my argument, here’s a smoking gun.

Below are a few panels from the first issue of Kamandi. In this scene, we get our first glimpse of the tiger chieftan, Great Caesar. Though he uses a gun, he dresses like a Roman military leader — breastplate and segmented torso armor (lorica segmentata, or sometimes lorica squamata), feathered helmet, cape, and so forth.

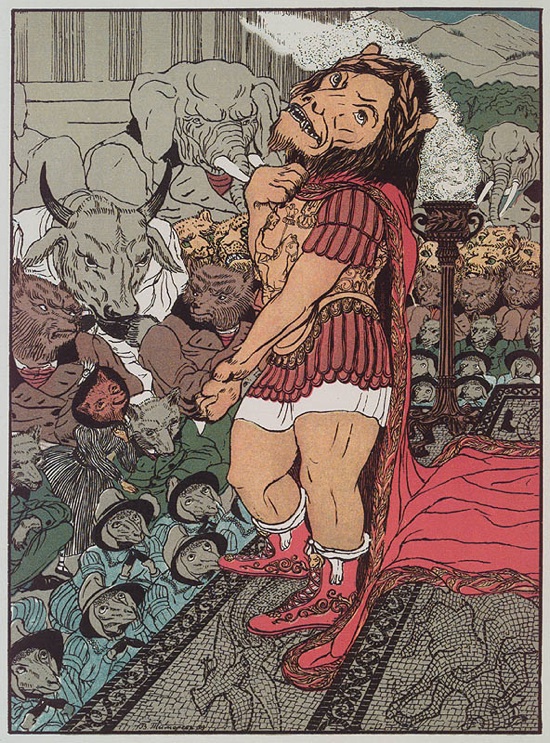

Now check out the chromolithograph, below. It’s by V. Timorev, from Ivan Andreevich Krylov’s 1913 book, Two Fables — that is, it’s from Radium Age fantasy fiction. I stumbled across it yesterday, while admiring A Journey Round My Skull’s Flickr photostream.

To quote Stan Lee: ’Nuff said!

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

In 2012–2013, HiLoBooks serialized and republished (in gorgeous paperback editions, with new Introductions) 10 forgotten Radium Age science fiction classics! For more info: HiLoBooks.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE