Radium-Age Supermen

By:

January 27, 2010

Long before Alan Moore asked “Who will watch the Watchmen?” Radium Age (1904-33) science fiction writers worried whether supermen would rescue us ordinary mortals — or try to dominate us.

This item first appeared on Gawker’s sci-fi blog io9.com, on Feb. 16, 2009.

Dreamed up by American and European SF writers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries — at a time when Lamarckian evolutionary philosophy, which posits a tendency for organisms to become more perfect as they evolve (because such change is needed or wanted, e.g., by “life”), remained popular — many of the first fictional supermen were portrayed by their creators as examples of a more perfect species towards which humankind has supposedly long aimed. Radium Age superman was, that is to say, homo superior, an evolved human whose superiority was mental, physical, or both. [Note: Bergson’s Creative Evolution, which suggested that life evolves in the direction of a greater capacity for action and freedom, was surely another important influence on these authors; but unlike Lamarck, and like Darwin, Bergson’s model of evolution didn’t imagine any predestined endpoint, e.g., a perfect being or absolute freedom.]

Aye, there’s the rub: for, as Nietzsche has Zarathustra predict, “Just as the ape to man is a laughingstock or a painful embarrassment, man shall be just that to [superman].” Olaf Stapledon, Philip Wylie, George Bernard Shaw, and other PGA SF authors agreed that the superman — whose values and worldview the rest of us can’t share, or even comprehend — would seem cold, inhuman, alien. Even, or especially when, he or she is trying to help us.

Well-known Golden Age superman fiction includes: Van Vogt’s The World of Null-A, Sturgeon’s More Than Human, Shiras’s Children of the Atom, and PKD’s The Golden Man. I also enjoy: Andrew Marvell’s Minimum Man, Stapledon’s Sirius and A Man Divided, Jack Williamson’s Darker Than You Think and Dragon’s Island, Jerome Bixby’s “It’s a GOOD Life” (basis of a famous Twilight Zone episode), Poul Anderson’s Brain Wave, Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man, and Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land and Friday.

The influence of Radium Age supermen remains a powerful one. Consider Adrian Veidt, in the Watchmen movie adaptation. Unlike most superheroes we’ll see on the big screen in the next year or so — e.g., Wolverine, Wonder Woman, Captain America, not to mention Superman himself — Ozymandias, as Veidt was known in his costumed adventurer days, isn’t merely a mutant, a godling, a scientific experiment, or an alien visiting a planet where he’s uniquely able to kick ass. Instead, he’s an Übermensch — a self-overcoming individual, that is to say, who has not only mastered his perfect body but (to quote Peter Cannon… Thunderbolt, the Charlton comic that inspired Moore’s Ozymandias) “harnessed the unused portions of the brain.” Fortunately or unfortunately for humankind (that’s the issue), he has also revalued our human, all too human values.

“I think you could see that it was an evil thing to do and maybe a patronizing thing to do,” Watchmen illustrator and co-creator Dave Gibbons said, when asked about Ozymandias’s catastrophic scheme to save the world. He continued:

I think that probably is one of the worst of his sins, that it’s kind of looking down on the rest of humanity, scorning the rest of humanity. I think for that reason that [Veidt’s former comrade, the masked vigilante] Rorschach, by persisting in his single-minded devotion to what he sees as the truth is … actually painted in a very human manner. At the end of it, your loyalty lies very much with this very flawed, psychopathic human being who knows his faults, who knows the faults of the rest of humanity, rather than somebody like Adrian, who considers himself to be above humanity and who has taken a rather cold and calculating view of everything.

Ozymandias may sound like Tom Cruise (who was interested in the role). What he’s utterly unlike, however, is your typical comic-book superhero — who, despite his or her superhuman abilities, tends to reflect and personify our own, human values. That’s because Superman was an invention of SF’s gung-ho, can-do Golden Age. His Radium Age literary precursors, however, were a different story altogether.

Here’s a list – in no particular order — of the 10 most influential and problematic supermen and women from 1904-33. There’s a complete list at the end.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

1) HUMPTY, in Olaf Stapledon’s Last Men in London (London: Methuen, 1932). Stapledon writes insightfully about homo superior – he’s credited with coining the term – in three of the four novels for which he’s remembered. I’ve already written, in this series, about Last and First Men and Odd John, so that leaves Humpty. He’s a young “supernormal,” a London teenager in whom there is “some promise of a higher type.” According to Stapledon, all “submerged supermen” are adolescent misfits, because: they don’t take themselves seriously, they don’t want to get ahead, they despise athletics, they’re puzzled and bored by religion and patriotism, they don’t regard sexuality as shameful, and they remain idealistic long after childhood. They’re Lost-Generation-style idlers, in other words. But with really big heads. In a Good Will Hunting-like coda to the novel, whose protagonist is Paul, a teacher telepathically possessed by a member of an evolved human species (the Last Men) living in the distant future, the brilliant Humpty outlines a plan to found a new human species that will control the world and eliminate or domesticate the “subhuman hordes”… then succumbs to despair.

READ IT | BUY IT

2) THE WONDER, in J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder (Sidgwick and Jackson, London, 1911). Victor Stott is a giant-headed “supernormal” child mutated in the womb by his parents’ desire to have a son born without habits. After surveying science, philosophy, history, literature, and religion, the Wonder says, “So elementary… inchoate… a disjunctive… patchwork.” His adult interlocutors are shattered by his statements about the nature of the universe and human progress; his philosophy begins with rejecting “the interposing and utterly false concepts of space and time,” and ends with the notion that life and all matter are merely “a disease of the ether.” Unable to live without illusions, everyone rejects the Wonder’s disenchanting insights; he also makes an enemy of the local clergyman, who may murder him. “He was entirely alone among aliens who were unable to comprehend him, aliens who could not flatter him, whose opinions were valueless to him.” Scholars call this the first SF novel of real importance about intelligence; it’s the ancestor of Clarke’s Childhood’s End and Van Vogt’s Slan.

READ IT | BUY IT

3) RALPH, in Hugo Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660 (Stratford Co.: Boston, 1923. Serialized in Modern Electrics, 1911-12.) Ralph One-to-foresee-for-an-other (get it?) is a great American scientist, and a superior type; the “plus” at the end of his name proves it. But what kind of big-headed superman story is this, anyway? The polar fleece-wearing citizens of solar-powered, geothermally heated New York don’t fear or resent Ralph; in fact, they’ve erected a glass-and-steelonium luxury tower for him in Union Square. Ralph isn’t an evil genius; he’s something of a bore, and so is his techno-utopian society. Except maybe when his girlfriend is kidnapped by a Martian! Despite the wooden prose and juvenile adventure, this Edisonade is worth a read because of all the technology it accurately predicts: e.g., fluorescent lights, microfilm, radar, television. Also, I suspect that we’re on the cusp of seeing the Hypnobioscope, which allows you to avoid subscribing to newspapers in your sleep, hit the Apple Store.

4) ZOZIM and ZOO, in George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (Constable: London, 1921). Shortly after WWI, the secret of Creative Evolution — in Shaw’s formulation, the process by which an organism can will its own entelechy, or self-potentiation — is discovered. By the year 3100 the long-lived elite have developed perfect physiques and advanced mentalities. Zozim and Zoo are Boomer-like superhumans (he’s nearly 100, she’s 50, but they act like young adults) who assist a sham oracle in overawing the short-livers seeking its advice. It’s all part of a plot to colonize and supersede ordinary humans! But like the proto-Yippies they are, Z and Z are upfront about the put-on. Zoo: “[Zozim] has to dress-up in a Druid’s robe, and put on a wig and a long false beard, to impress you silly people…. I have no patience with such mummery; but you expect it from us; so I suppose it must be kept up.” It’s Wild in the Streets meets Highlander. Fun fact: RFK was quoting Shaw’s play when he said, “”You see things; and you say, ‘Why?’ But I dream things that never were; and I say, ‘Why not?'”

READ IT | BUY IT

5) THE AMPHIBIAN, in S. Fowler Wright’s The Amphibians (Merton Press: London, 1925). Half a million years in the future, a nameless, time-traveling protagonist discovers that the Earth’s dominant intelligent species are the Dwellers (humanoid giants with equally giant intellects, self-destructively devoted to science) and the furry Amphibians (not merely mentally and physically more evolved than modern man, they’re also morally superior). Though they regard the time traveler as a primitive (hello, Planet of the Apes), one of the Amphibians accompanies him across a Divine Comedy-like landscape of incredible horrors and warfare between monstrous species. It’s an allegorical adventure, in which conflicting philosophies of life and morality are debated: the Spock-like Amphibian is dispassionate and sees things from a transcendental perspective, while the Kirk-like Primitive is emotional and impulsive. Fun fact: Everett F. Bleiler calls The World Below (The Amphibians + its sequel, published together in ’29) “undoubtedly the major work of science fiction between the early Wells and the moderns.”

BUY IT | MORE ABOUT SFW

6) BORK/DE SOTO, in John Taine’s Seeds of Life (1951; serialized in Amazing Stories Quarterly, Fall 1931). “We do not like the thought of being relegated to a minor place in the evolutionary scheme; we half expect that a race of geniuses would treat us cruelly, as we treat dumb animals,” writes Peter Nicholls. “Taine’s Seeds of Life is a prototype of this kind of story.” Maybe not, but it’s a ripping yarn that may have influenced everything from Flowers for Algernon to Spider-Man. Neils Bork, a pathetic lab technician, attempts suicide via X-rays and is transformed into a supermind in the body of a swarthy Adonis; he renames himself De Soto. (“De Soto was but a partial, accidental anticipation of the more sophisticated and yet more natural race into which time and the secular flux of chance are slowly transforming our kind.”) He invents wireless energy transfer devices, secretly planning to use them to bombard humankind with “dysgenic” rays that will devolve unborn children. Then De Soto’s own evolution reverses itself: “I never used to think, but saw the inevitable consequences of any pattern of circumstances – no matter how complicated – immediately, like a photograph of the future.” He repents of his superioristic ways, and is killed by his own reptilian offspring. Fun fact: John Taine was the pseudonym of CIT mathematician Eric Temple Bell.

BUY IT

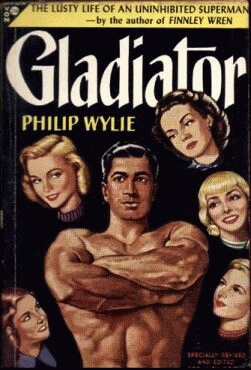

7) HUGO, in Philip Wylie’s Gladiator (Knopf: New York and London, 1930). Wylie is best known as coauthor of When Worlds Collide, and as a crank(y) essayist obsessed with Soviet nukes and “Mom-ism.” The only thing you ever hear about this Radium Age SF classic is that it’s “thought to be the book from which ‘Superman’ was derived.” Make no mistake: Siegel & Shuster lifted everything except Superman’s cape from Gladiator. Thanks to an experiment by his scientist father (who studies grasshoppers and ants), Hugo Danner is nearly invulnerable, runs faster than a train, leaps higher than trees, and hurls boulders like baseballs. Also, his father gives him Nietzschean advice only, e.g.: “The stronger, the greater, you are, the harder life is for you.” So… Hugo creates a fortress of solitude in Colorado, drops out of school, wanders the planet, then joins the French Foreign Legion at the outbreak of WWI (“He felt himself almost the Messiah of war…. He was like a being of steel”). Later, he adopts a secret identity, moves to Metropolis Manhattan, and vows to become “an invisible agent of right — right as best I can see it.” Despairing, however, of flawed mortals and their politics — I’d probably call him an anarcho-monarchist — Hugo heads to the Yucatan to start a colony of superbeings, “the new Titans.” But then he changes his mind and curses God… on a mountaintop, shown at left, instead.

READ IT | BUY IT

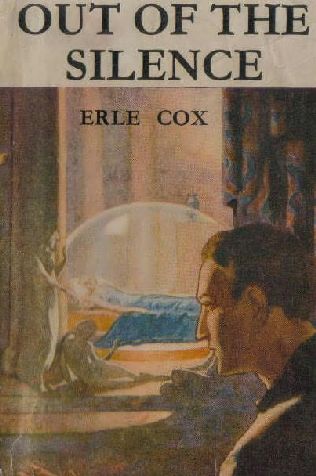

8) EARANI, in Erle Cox’s Out of the Silence (E.A. Vidler: Melbourne, 1925; serialized in The [Melbourne] Argus, 1919). Alan Dundas stumbles upon the subterranean repository of a long-vanished, fantastically advanced civilization. He awakens Earani from a state of suspended animation. Her intelligence and abilities are as astounding as her beauty. (Hello, Leelo in The Fifth Element.) In fact, Earani was the end result of her civilization’s worldwide eugenics program, which she intends to put back into practice, as soon as she conquers the planet. (“This world of yours is full of pain and misery…. Is any price too great that buys a perfect and wholesome humanity?” Earani demands of Australia’s prime minister. “You hold that to carry out my mission would be a crime. I hold that to fail in doing so would be a crime.”) Alan, who falls in love with Earani, is undisturbed by her plan to wipe out the “colored races” and inferior whites; one is not sure what the author himself thinks about this subject. In the end, Earani is backstabbed (literally) by another woman.

READ IT | BUY IT

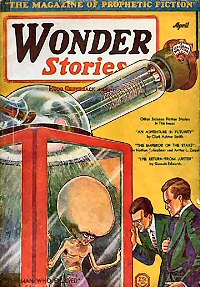

9) POLLARD, in Edmond Hamilton’s “The Man Who Evolved” (Wonder Stories, April 1931). Dr. John Pollard is a biologist trying to crack one of the two great mysteries of evolution: “What is the cause of evolutionary change?” Having determined that the answer is “the cosmic rays,” and having built a cosmic ray-gathering contraption, Pollard invites two friends (one of whom is the narrator) to witness as he investigates the second question: “What is the future course of man’s evolution going to be?” Pollard first evolves himself into a superman, with a godlike physique and immense intellectual power; then into a shriveled body supporting an enormous head; then a huge head with almost no body, which plans to “master without a struggle this man-swarming planet, and make it a huge laboratory in which to pursue the experiments that please me”; then into a brain with tentacles, a Dr. Manhattan-like being whose perspective is so cosmic that it no longer cares to dominate the world. (“The only emotion, if such it is, that remains to me still is intellectual curiosity…”) Alas, after evolving himself one more time, Pollard devolves back into simple protoplasm. Fun fact: Isaac Asimov described this as “the first science fiction short story… that impressed me so much it stayed in my mind permanently.”

READ IT

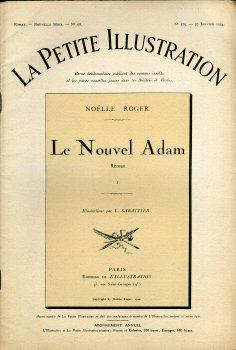

10) HERVE, in Noëlle Roger’s Le nouvel Adam (1924; translated as The New Adam, London: Stanley Paul & Co. Ltd., 1926). When Herve Silenrieux, a hapless medical student working for Dr. Flecheyre at Paris’s Institut Pasteur, attempts suicide by shooting himself in the head, Flecheyre implants in him an experimental combination of glands that he believes will stimulate the brain — and in so doing, create an evolved human. Indeed, Herve becomes incredibly brilliant… but wholly logical and unpleasant. For example, he no longer hesitates to kill patients for experimental data. Dismissed from the hospital, Herve develops a death ray, which he tests on villagers in the French countryside; after that, he detonates lumps of lead with the force of an atomic bomb, setting off a series of earthquakes. Attempting to prevent Herve from wiping out the human race, Flecheyre confronts him; Herve’s forcefield detonates the lead bullets in Flecheyre’s pistol, and both men die. Fun fact: Noëlle Roger is the pseudonym of Hélène Dufour Pittard, a Swiss-Canadian journalist.

ALSO OF INTEREST

“Some individuals, it is true, are more special. This is natural selection. It begins as a single individual, born or hatched like every other member of their species, anonymous, seemingly ordinary. Except they’re not. They carry inside them the genetic code that will take their species to the next evolutionary rung. It’s destiny.” — fictional geneticist Mohinder Suresh (Sendhil Ramamurth), expressing an un-Darwinian view of evolution in the first episode of Heroes, 9/23/06.

NINETEENTH CENTURY (1804-1903)

* Don Quichotte, “The Artificial Man: A Semi-Scientific Story” (1884)

* Edward Payson Jackson, A Demigod: A Novel (1886)

* Ernest G. Harmer, Professor Bommsenn’s Germ (1888).

* Joseph Shield Nicholson, Thoth: A Romance (1888)

* Camille Flammarion, Omega: The Last Days of the World (1893).

* Frank Challice Constable, The Curse of Intellect (1895)

* J.H. Rosny aîné, “Un Autre Monde” (1895)

* Oto Mundo, The Recovered Continent: A Tale of the Chinese Invasion (1898)

* Louis Boussenard, Ten Thousand Years in a Block of Ice (1898)

* Alfred Jarry, The Supermale (1902)

* Aston Forrest, The Extraordinary Islanders. Being an Authoritative Account of the Cruise of the ‘Asphodel,” as Related By Her Owner (1903)

* Godfrey Sweven, Limanora: The Island of Progress (1903)

THE NINETEEN-OUGHTS (1904-13)

* H.G. Wells, The Food of the Gods and How it Came to Earth (1904)

* Alfred William Lawson, Born Again: A Novel (1904)

* Tyman Currio (John Russell Coryell?), Weird and Wonderful Story of Another World (1905-06)

* E. Nesbit (as E. Bland), “The Third Drug” (1908)

* M.P. Shiel, The Isle of Lies (1909)

* J.D. Beresford, The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911)

* James L. Ford, “The Highbrow” (1911), a Smart Set story which can be read as a Radium Age sf story about a mutant species.

* William Greene, “The Savage Strain” (1911)

* Hugo Gernsback, Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660 (1911-12)

THE TEENS (1914-23)

* Harry Keeler, “John Jones’s Dollar” (1915)

* J.A. Mitchell, Drowsy (1917)

* Frederic Carrel, 2010 (1914)

* George Allan England, The Fatal Gift (1915)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs, The Land That Time Forgot (1918; 1924)

* Marie Corelli, The Young Diana: An Experiment of the Future (1918)

* Austin Hall, Into the Infinite (1919)

* Erle Cox, Out of the Silence (1919)

* H. Rider Haggard, When the World Shook (1919)

* G. Stanley Hall, “The Fall of Atlantis” (1920)

* George Bernard Shaw, Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (1921)

* Georges Lebas, Jean Arog, le premier surhomme (1921)

* E.V. Odle, The Clockwork Man (1923)

* H.G. Wells, Men Like Gods (1923)

THE TWENTIES (1924-33)

* John Lionel Tayler, The Last of My Race: A Dream of the Future (1924)

* Noelle Roger, Le nouvel Adam (1924, translated as The New Adam (1926)

* S. Fowler Wright, The Amphibians: A Romance of 500,000 Years Hence (1925)

* J.C. Snaith, Thus Far (1925)

* Henry Carew, The Vampires of the Andes (1925)

* Guy Dent, Emperor of the If (1926)

* Muriel Jaeger, The Man with Six Senses (1927)

* Edmond Hamilton, “Evolution Island” (1928)

* Wallace West, “The Incubator Man” (1928)

* Edmund Snell, Kontrol (1928)

* Philip Wylie, Gladiator (1930)

* Olaf Stapledon, Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future (1930)

* John Gloag, To-Morrow’s Yesterday (1930)

* John Taine, The Iron Star (1930)

* Paul Ernst, The Black Monarch (1930)

* John Hargraves, The Imitation Man (1931)

* John Taine, Seeds of Life (1931)

* Edmond Hamilton, “The Man Who Evolved” (1931)

* Olaf Stapledon, Last Men in London (1932)

* Philip Wylie, The Savage Gentleman (1932) [inspired Doc Savage series]

* Lester Dent’s Doc Savage series, which began in March ’33.

* Muriel Jaeger, Hermes Speaks (1933)

* John Russell Fearn, The Intelligence Gigantic (1933)

EARLY GOLDEN AGE/LATE RADIUM AGE

* Olaf Stapledon, Odd John (1935)

* Claude Houghton, This was Ivor Trent (1935)

* Stanley G. Weinbaum, “The Adaptive Ultimate” (1936)

* M.P. Shiel, The Young Men Are Coming (1937)

* H.G. Wells, Star-Begotten (1937)

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE