10 Best Adventures of 1994

By:

July 30, 2020

Twenty-six years ago, the following 10 adventures from the Nineties (1994–2003) were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Tibor Fischer’s crime adventure The Thought Gang. Eddie Coffin, an unemployed, alcoholic, sybaritic Cambridge philosophy professor, flees scandal in Britain for France; there, he meets Hubert, a one-armed (and one-legged) robber who’s recently been release from prison. Applying the metaphysical and existential insights of the great philosophers to the problems of bank robbery, the hapless duo embarks on a shambolic, mostly successful crime spree across the country. Eddie, one may be intrigued to hear, handles the robberies, while Hubert does the philosophizing. Fischer is not only a very funny writer, but a very erudite one; you’ll actually learn quite a bit about philosophy from this yarn… and you’ll marvel at his verbal pyrotechnics, not least his drive to incorporate words beginning with “z” into the narrative. (This is a plot device, not just a gimmick.) It’s all a bit too much, perhaps — but Fischer’s second novel is an utterly unique, highly entertaining story to which I’ve returned several times since it was published. Forget Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon’s sorta-funny foodie tours of the Continent; why hasn’t The Thought Gang been adapted as a TV series? Fun facts: Reviewers at the time tended to suggest that Fischer had lost control of his themes, while at the same time praising The Thought Gang in the highest possible terms — suggesting it was one of the funniest, most imaginative novels of the era. It deserves to be rediscovered by today’s readers.

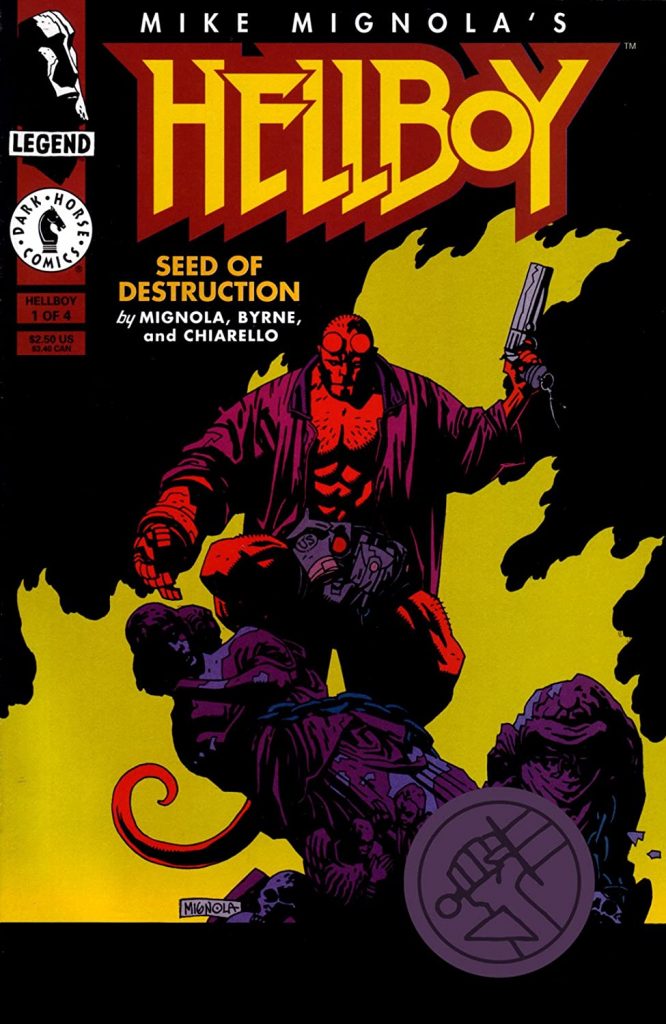

- Mike Mignola’s Hellboy comics (1994–present). The Dark Horse Comics story “Seed of Destruction” (serialized March–June 1994), written and drawn by Mignola with script by John Byrne, introduces us to one of the great comic-book characters of the era: the half-demon Hellboy. (Yes, there were one or two previous appearances, but here is where the Hellboy epic begins.) Summoned from Hell by Nazi occultists, then raised by Professor Trevor Bruttenholm, who after WWII would form the Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense (B.P.R.D.), Hellboy is a gruff, emotionally immature, but kind-hearted creature… whose grafted-on right hand is an apocalyptic demon-relic. He’s also the World’s Greatest Paranormal Investigator. Accompanied by a troubleshooting team of law enforcement officials, soldiers, mutants, and “scholars of the weird” (e.g., folkorist Kate Corrigan, the amphibian Abe Sapien, and the pyrokinetic Liz Sherman), Hellboy battles grotesque foes in a series of tall tales inspired by folklore, pulp magazines, Lovecraftian horror, and horror fiction. Mignola’s drawing style — thin lines, unwieldy shapes, a heavy use of black forms — has become iconic. Fun facts: Ron Perlman was an inspired casting choice for the 2004 and 2008 live-action Hellboy movies, directed by Guillermo del Toro. David Harbour’s performance in the 2019 reboot was also fun, but the movie wasn’t as good as the original two. The Hellboy character has also starred in animated films and three video games.

- Lionel Davidson’s espionage thriller Kolymsky Heights. After a 16-year hiatus from writing adventures for adults, Davidson returned with his final novel — a beautifully written, action-picked yarn to rival his best works, including The Rose of Tibet (1962), A Long Way to Shiloh (1966), and Making Good Again (1968). Dr. Johnny Porter, a Canadian professor of anthropology who has mastered the languages and dialects of the various tribes of Northern Canada, Alaska and Siberia, as well as Korean, Russian, and Japanese, is himself descended from Inuits — who remain physically, ethnically and culturally similar to their Siberian counterparts. He is, therefore, the only westerner who can hope to break into — and back out of — a Soviet scientific research base (ostensibly a weather station) in Siberia, one so secret that no one who enters is ever allowed to leave again. After receiving some training by the CIA, a reluctant Porter heads from Japan to Siberia disguised as a Korean sailor; this is only phase one of a multi-stage plan which will see our hero adopt multiple disguises, and survive by his wits. It’s a hunted-man story and man-agaist-nature story to rival anything by Buchan, Ambler, or Hammond Innes. Fun facts: Writing for The New York Times Book Review, James Carroll enthused that Kolymsky Heights — Davidson’s final novel — is “written with the panache of a master and with the wide-eyed exhilaration of an adventurer in the grip of discovery. Mr. Davidson has not only rescued one of the most familiar narrative forms of the era, the spy thriller; he has also renewed it.”

- Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy western adventure The Crossing. In the years just before and during WWII, teenage Billy Parham ventures across the New Mexico border into Mexico on three adventures — much like Walter Scott’s characters, impatient with over-civilized England, headed into the Scottish highlands. The first section, which has frequently been compared with Faulkner’s “The Bear” finds Billy communing with a wolf he’s trapped… and returning it to Mexico rather than killing it. When the wolf is taken from him and sold to a circus, where it’s going to be killed in a bloody spectacle, Billy makes one last — sacrificial — effort to protect its dignity. Returning home, Billy discovers that tragedy has befallen his family; springing his younger brother, Boyd, from a foster home, the two head back to Mexico to recapture their family’s horses. They rescue a Mexican girl with whom Boyd falls in love; they also end up in a bloody confrontation with a ranch chief who is unwilling to let them take their horses back. It’s a saga-like story, with no happy ending or uplifting moral; like Mark Renton in Irvine Welsh’s (also saga-like) Trainspotting, Billy learns only that most people live blunted, unfulfilling lives. The language and vocabulary, as always with McCarthy, is extraordinary. Fun facts: Billy’s story, as well as that of John Grady Cole, from All the Pretty Horses, continues in the final volume of the trilogy, Cities of the Plain (1998).

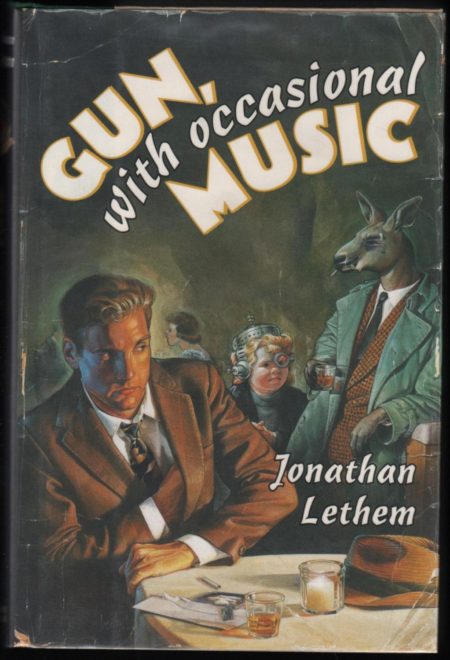

- Jonathan Lethem’s sci-fi/neo-noir adventure Gun, with Occasional Music (1994). The author’s first novel is a pastiche of hardboiled crime fiction and cyberpunk; it’s affectionate towards the former, tongue-in-cheek towards the latter. In a not-too-distant future Los Angeles and Oakland, smart-mouthed private “inquisitor” Conrad Metcalf looks into the murder of Dr. Maynard Stanhunt, a prominent urologist who turns out to have been in cahoots with the gangster Danny Phoneblum. The victim’s ex-wife and the murder suspect’s sister are raising a “babyhead” — one of a cohort of infants whose development has been sped up, resulting in a Gen X-like subculture of cynical, unmotivated, whiny assholes. A thuggish evolved kangaroo (think Wilmer, the jumped-up “gunsel” from The Maltese Falcon) is tailing Metcalf, who’s got the hots for a sexy inquisitor with the unimprovable name Catherine Teleprompter. All these shenanigans take place in a dystopian America in which it’s all but forbidden to use words to describe news events; there’s a cultural taboo against asking questions; and everyone is on [the] Make, a legal drug that keeps users forgetful and contented. The inquisitors, who’ve settled upon a fall guy for the murder rap, subtract so many of Metcalf’s state-issued karma points that he may wind up doing time in the big freeze. But when Metcalf uncovers a scheme in which zero-karma convicts are implanted with “slaveboxes” and used as prostitutes (hello, Dollhouse), he plays it “existential. and maybe a bit stupid.” It’s the only way he knows how to play it. Fun fact: “I really, genuinely wanted to be published in shabby pocket-sized editions and be neglected — and then discovered and vindicated when I was fifty,” Lethem has said, about his early novels. “To honor, by doing so, Charles Willeford and Philip K. Dick and Patricia Highsmith and Thomas Disch, these exiles within their own culture. I felt that was the only honorable path.”

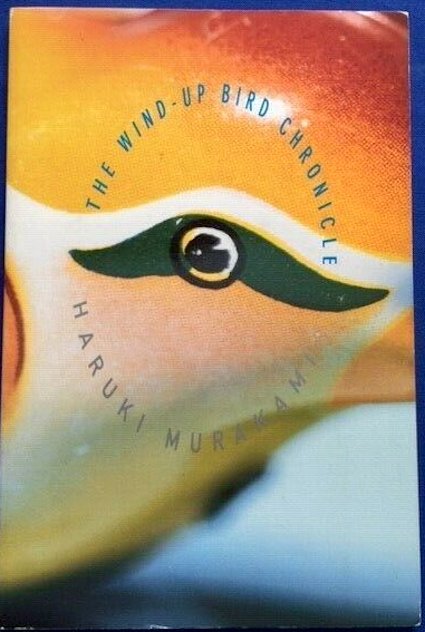

- Haruki Marukami’s apophenic adventure The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994–1995; in English, 1997). Toru Okada, a Bartleby-like slacker who lives in a Japanese suburb, has recently quit his tedious job and abandoned his dream of earning a law degree. His wife, Kumiko, is more ambitious and driven… but she has secret depths. Her brother, Noboru, a mediagenic academic who becomes a politician — and who is obsessed with Kumiko — is our shape-shifting antagonist. When Kumiko disappears, Toru embarks on a trippy, internal and external quest of discovery and self-discovery. If the way I’ve described this masterpiece of magical realism makes it sound like the Scott Pilgrim graphic novels, yes, it is sort of like that… except that it’s not about hipsters in the Toronto rock scene, and it’s not silly or shallow. I’d also compare The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle to Joyce’s Ulysses — the long digressions, the deep insights into the author’s national culture, and particularly the brilliant moments when a teenage girl’s POV takes over the story. Why did Kumiko leave? Did she ever love Toru? Who keeps calling Toru with mysterious leads and clues that make him more, rather than less confused? There are many interesting (mostly female) characters; a gripping war story related by an old soldier about his experiences in Mongolia during the Sino-Japanese War; and a bird whose mechanical-sounding cry punctuates the drama like a Greek chorus. Fun facts: Murakami, the most widely-read Japanese novelist of his generation, rejects the idea that he’s influenced by Kafka: “Kafka’s fictional world is already so complete that trying to follow in his steps is not just pointless, but quite risky, too,” he’s said. “What I see myself doing, rather, is writing novels where, in my own way, I dismantle the fictional world of Kafka that itself dismantled the existing novelistic system.”

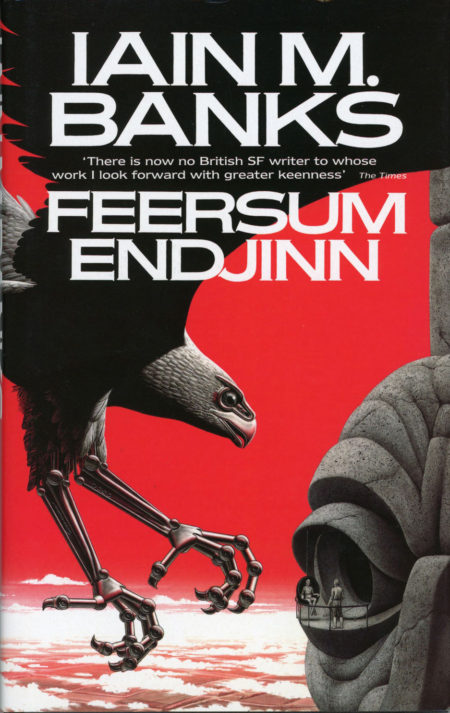

- Iain M. Banks‘s sci-fi adventure Feersum Endjinn. Too many fans of Banks’s Culture series pooh-pooh this, his second non-Culture story — complaining in particular about the Riddley Walker-esque patois in which the character Bascule the Teller speaks. True, it’s not as fun as the Culture books… but like them it’s a staggering work of imagination, and a lot of fun. This one takes place in a vast, Gormenghastian castle-like structure known as the Fastness, around which the novel’s protagonists clamber like ants (one thinks of Aldiss’s Non-Stop), and also in the Cryptosphere, a vast dataspace that can be explored virtually, via avatar, and to which millions of personalities have been uploaded — but which is succumbing to entropy and chaos. Sessine, an assassinated military commander, wakes up in the Cryptosphere… only to be assassinated there, too; in this post-singularity future, we discover, a person can die several times, not only in the real world but virtually. We also encounter a top-ranked scientist, Hortis Gadfium, who is conspiring against the King; she is privy to new intel about an approaching catastrophe known as the Encroachment. Asura, a Leeloo-like figure, is tasked with activating the titular “fearsome engine” that will save the solar system… but she has amnesia; captured, she is subjected to a series of virtual-environment storytelling efforts to learn her secret. Meanwhile, Bascule, a Teller (whose job it is to project himself into the Cryptosphere in search of lost information), gets caught up in the political machinations and seeks refuge among chimeric animals. The final chase scene — involving a vacuum balloon ascending a space elevator — is terrific. And honestly, Bascule isn’t that hard to understand! Fun facts: “I used to have these model soldiers, and I wondered what it would be like to be one of those tiny soldiers in a giant house,” Banks would later explain in an interview. “I used to have these epic journeys for them. I thought if you had a giant structure, basing it on furniture would be easy.”

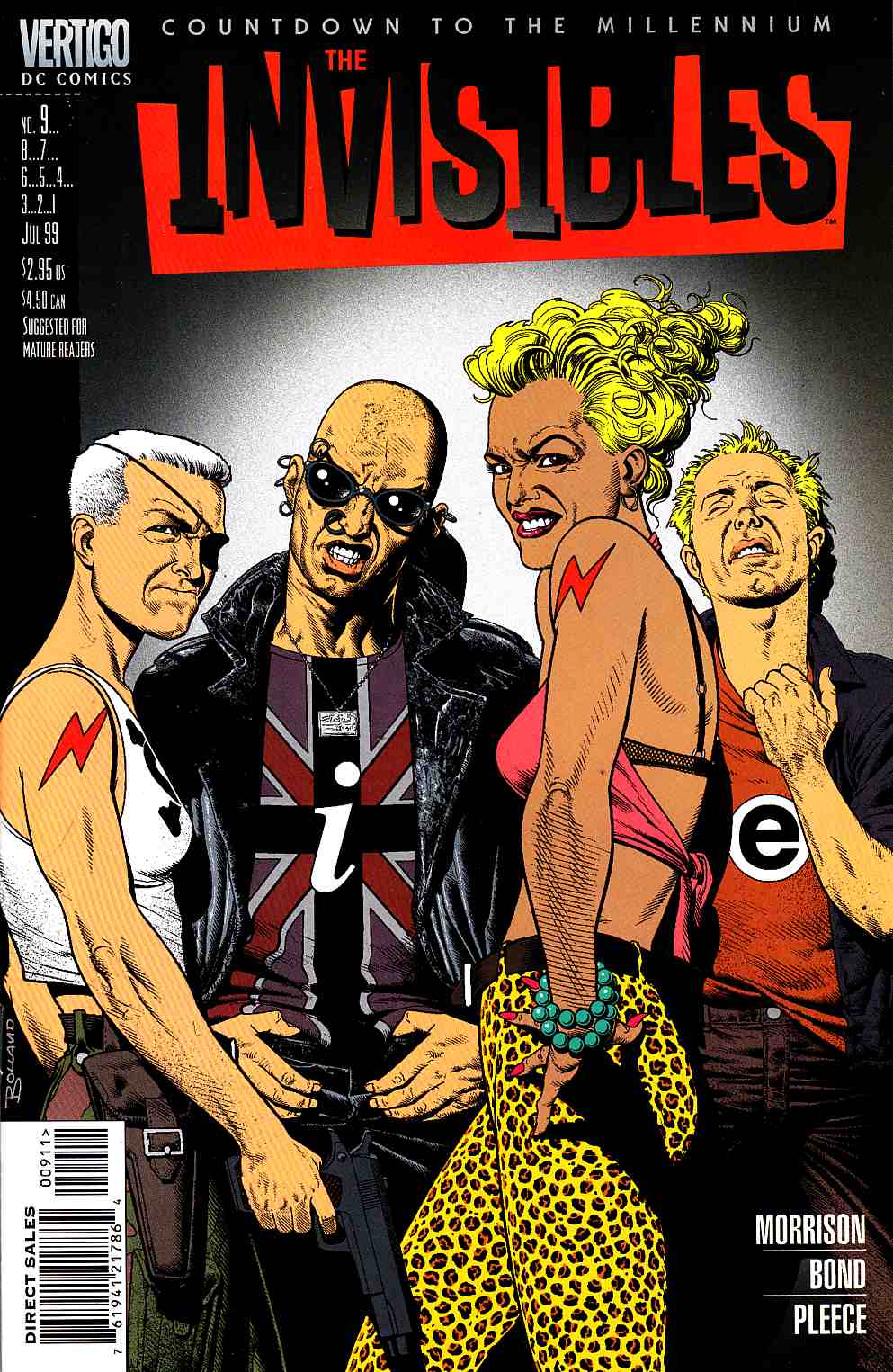

- Grant Morrison‘s comic The Invisibles (serialized 1994–2000). Scottish comic book writer Grant Morrison is one of the triumvirate of British creatives — along with Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman — whose trippy, subversive, meta-textual sensibilities helped mutate and transform American comics. A self-proclaimed chaos magician, Morrison gave us a world in which objective truth is unknowable, illusion and reality are interchangeable, “bad guys” are good and “good guys” bad. The Invisibles are group of transgressive, libertine, punk freedom fighters led by the Jerry Cornelius-like King Mob; they’re part of a larger organization, The Invisible College, which uses time travel, magic, and violence to battle the Archons of the Outer Church, interdimensional alien gods who’ve persuaded most of us to internalize their oppression. Other characters include: Lord Fanny, a transgender Brazilian shaman; Tom O’Bedlam, a homeless man; Boy, a former New York cop; and Ragged Robin, a telepath. In the first run of stories, the group recruits Jack Frost, a hooligan… who learns that he may be the reincarnation of the Buddha. The references — political, pop-cultural, sub-cultural — come thick and fast. A slow-moving adventure, richly rewarding. Fun facts: The Vertigo imprint of DC Comics published 59 issues of The Invisibles, in all. Morrison scripted the stories, and various artists illustrated them.

- Nick Tosches’s crime adventure Trinities. Before Tony Soprano, there was Johnny DiPietro — a Brooklyn-based Mafia hit man struggling with relationship problems, family loyalty, rival mafiosi out to betray or kill him, and morality. Through DiPietro’s eyes, we watch his uncle Joe — a grump, retired Mob boss who regrets having allowed the Chinese Triads to take over the heroin trade — cannily and ruthlessly get the gang back together. Joe’s Chinese counterpart, the aging Chinatown junkie and gang boss Chen Fang, is the second POV in Tosches’ unholy trinity; the third is that of D.E.A. agent Bob Marshall. We’re also introduced to several well-realized minor characters… most of whom die violently once war between the Mafia and the Chinese Triad gangs breaks out. Meanwhile, Johnny and his Uncle Joe are butting heads with the new Mafia leadership: young men with MBAs and an aversion to violence. Tosches is a fine story teller, one who takes the time to get into granular detail about everything from the most effective method of assassinating someone (and getting away with it) to cooking squid, laundering money, and using brand-name chemical products to cook up commercial quantities of China White. Fun facts: Tosches, who died in 2019, is best known as the tremendously talented author of such biographies as Hellfire: The Jerry Lee Lewis Story (1982), Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams (1992), and a journalist who covered music, the opium trade, and organized crime.

- Melissa Scott’s cyberpunk sci-fi adventure Trouble and Her Friends. At some point during the early 21st century, computer hacking — “cracking” — becomes as vigorously policed as burglary or bank robbery. So India Carless (a.k.a. Trouble), who’s one of the best crackers in the business, takes it on the lam. She leaves her partner, Cerise (a.k.a. Alice-B-Good), and their close-knit queer cracker group, for a legitimate career. (There’s a closing-of-the-frontier western vibe to this story.) Three years later, however, a cracker using her online identity, even her style of hacking, appears on the scene; pursued by her own employer, Trouble goes in search of answers. The interface that Scott describes — crackers use “dollie ports” and “brain worms” in order to feel physical sensations while navigating virtual reality — is intriguing; and I like how the narrative — as usual in cyberpunk — toggles between reality and VR. In what was an unusual move, at the time, Scott makes most of her characters queer women; they aren’t merely objects of desire for a male protagonist. On the other hand, Trouble and her friends — we learn from flashbacks — are the targets of proto-Gamergate sexism and misogyny. Despite her vanishing act, will Trouble’s community rally to help her out? Fun facts: Winner of the 1995 Lambda Literary Award for Gay & Lesbian Science Fiction and Fantasy. Scott would win this award again in 1996, for Shadow Man.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.