The Radium Age

By:

December 23, 2012

The following essay first appeared in the September 2012 issue of the international scientific journal Nature. Click here for a PDF of the original, which includes a sidebar not reproduced here.

We think we know science fiction. There were the “scientific romance” years that stretched from around the mid-1860s to 1903, after which H.G. Wells lost his touch. And there was the “golden age,” from 1934 to the mid-1960s. But between those periods — and overshadowed by them — was a fascinating era that gave us such enduring memes as the berserk robot, the tyrannical superman and the sinister telepath.

I call that period, from 1904 to 1933, sci-fi’s “radium age.” It emerged when the speed of change in science and technology was inducing vertigo on both sides of the Atlantic. More cynical than its Victorian precursor yet less hard-boiled than the generation that followed, this is sci-fi offering a dizzying, visionary blend of acerbic social commentary and shock tactics. It yields telling insights into its context, the early twentieth century. Plus, it is fun to read.

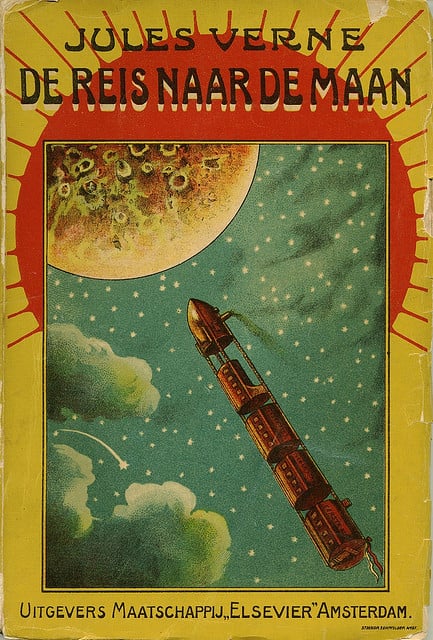

The scientific romances that preceded this era were strong on the fantastical but otherwise very different. The utopian fantasies of Edward Bulwer-Lytton (The Coming Race, 1871), for instance, and the fantastic voyages by writers such as Jules Verne (Journey to the Centre of the Earth, 1864) and Edgar Allan Poe (The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall, 1835) were largely sentimental literature. They were by and for people who were inspired by US inventor Thomas Edison and believed that modern science and technology would improve the human condition and usher in the triumph of millennia-old Christian values.

Radium-age writers were not out to beguile. They depict a human condition subverted or perverted by science and technology, not improved or redeemed. Aldous Huxley’s 1932 Brave New World, with its devastating satire on corporate tyranny, behavioral conditioning and the advancement of biotechnology, is far from unique. Radium-age sci-fi tends towards the prophetic and uncanny, reflecting an era that saw the rise of nuclear physics and the revelation that the familiar — matter itself — is strange, even alien. The 1896 discovery of radioactivity, which led to the early twentieth-century insight that the atom is, at least in part, a state of energy, constantly in movement, is the perfect metaphor for an era in which life itself seemed out of control.

As demonstrated by Philipp Blom in The Vertigo Years: Europe 1900–1914 (Basic Books, 2008), the actual experience of time and space was altered in this period by the proliferation of a range of stunning technological developments, from the telegraph and the telephone to aeroplanes and cinematic film. Thinking and perception were radically reoriented by developments in science, philosophy and the arts. These included Einstein’s special theory of relativity; the work of phenomenological philosophers such as Edmund Husserl, who sought to objectively describe the subjective workings of consciousness; and Cubism, the artistic movement spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque that explored distortion and deconstruction. Even social and cultural forms and norms, such as women’s subordination to men — once regarded as natural, permanent “elements” — were disintegrating.

During this astonishing period, sci-fi writers were obsessed with the future. The scientific romantics had conjured up simplistic utopias that remained firmly grounded in contemporary realities. By contrast, the radium-age novels, stories, movies and plays often lift off into previously unexplored realms.

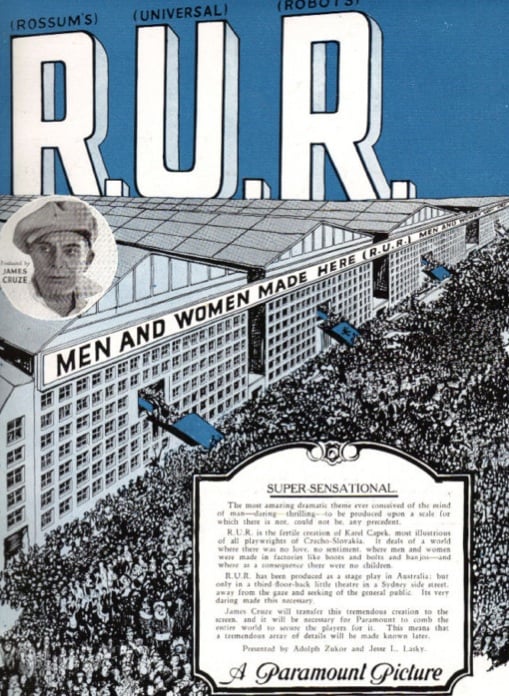

Instead of offering progressive solutions to social unrest, writers satirized and exaggerated its causes and effects. The out-of-control robot can be read as a criticism of the efficiency-oriented theories of Frederick Winslow Taylor and the practices of industrialist Henry Ford. So R.U.R. (Czechoslovakian writer Karel Čapek’s 1920 play, which introduced the term “robot” to the English language) portrays mass production as alienating at best. In Jack London’s post-apocalyptic The Scarlet Plague (1912), a race of barbarians descended from San Francisco’s brutalized underclass roam the city’s devastated remains after the fatal pandemic of 2013. And Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s feminist novel Herland (1915) imagines an ideal community in which women aren’t merely emancipated, but have done away with men altogether.

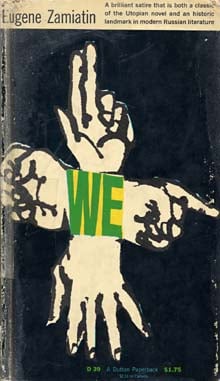

Politics are inevitably part of the mix — this is an era that encompassed the First World War, the Russian revolutions, and the rise of radical left- and right-wing movements. Many sci-fi authors, such as Čapek and Yevgeny Zamyatin, were leftists and liberals. But more conservative authors shared their utopianism and cynicism. For instance, Arthur Conan Doyle, inventor of Sherlock Holmes, wrote a series of ripping yarns starring a Professor Challenger, who discovers surviving dinosaurs, travels to Earth’s “sensory cortex” and witnesses the end of life on the planet — all the while making the case for reconciling imagination and intuition with a skeptical scientific method.

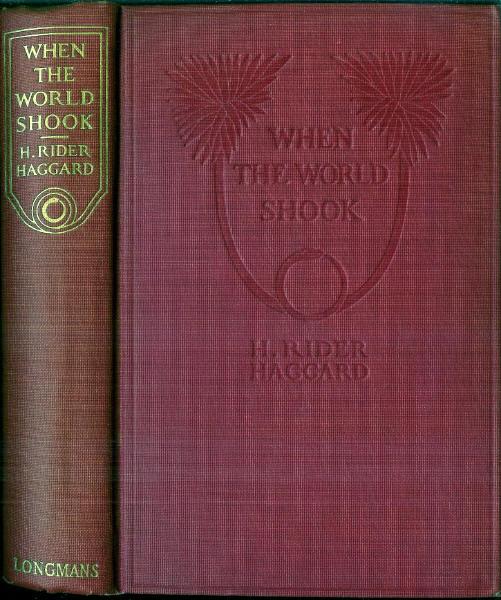

Similarly, H. Rider Haggard, who had made his name with King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and the Quartermain novels of the 1880s, created a disputatious trio in 1919’s When the World Shook — an idealistic Anglican minister, a sardonic doctor and an adventurer whose world view hovers somewhere in between. Meanwhile, both the leftist London (in The Scarlet Plague) and the conservative English poet Edward Shanks (in The People of the Ruins) agree that the destruction of modern western society wouldn’t be an entirely bad thing.

Fans of Philip K. Dick or Ursula K. Le Guin — writers belonging to what literary theorist Fredric Jameson has termed the “anti-anti-utopian” trend of the late 1960s and early 1970s — will find provocative antecedents here. Reading the dangerous visions of radium-age sci-fi, published in times as volatile as our own, destabilizes everything we take for granted. These books remind us that we need to regard our twenty-first-century forms and norms without sentimentality.

Click here for the HiLoBooks homepage.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE