RADIUM AGE: 1908

By:

June 11, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the years 1908–1909 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Oughts (1904–1913).

If we were to divide the Radium Age into quarters, 1908 would be the final year of its first quarter (1900-1908). How might we characterize this sub-era? Something for me to think about.

The Cavalier begins publication as an offshoot from Munsey’s The Scrap-Book, running for six years before being absorbed by All-Story. Launched as an all-fiction offshoot of the general-interest magazine, The Scrap Book (1906-1911), it was originally published on fine book paper with “classy” covers. The magazine switched to pulp paper in 1909, and, in 1911, Munsey added in-text illustrations and traded in its sophisticated covers for more exciting, colorful images of adventure. In January 1912, The Cavalier absorbed The Scrap Book, and became the first weekly pulp. Between 1908 and 1914, The Cavalier published over 40 scientific or fantastic stories. Contributors included George Allan England and Garrett P. Serviss.

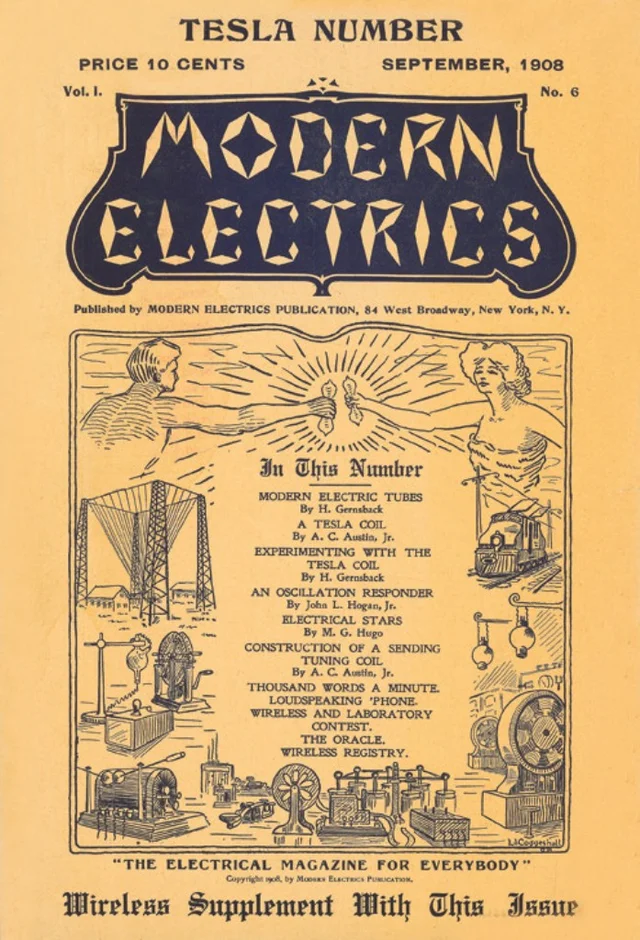

Also in 1908, Hugo Gernsback founds his first magazine, Modern Electrics. Long before Gernsback founded Amazing Stories, claims Grant Wythoff’s The Perversity of Things: Hugo Gernsback on Media, Tinkering, and Scientifiction (2016), “the project of science fiction as Gernsback understood it [had its origins in] a series of interlinking devices, debates, and visions shared by a community of tinkerers that formed around Gernsback’s electrical supply shop and technology magazines.”

“For Gernsback and his staff, rapid developments in the electrical arts made the speculative sciences of antigravitation and “thought waves” seem within reach. From a belief in the presence of the luminiferous ether, to an argument that gravity is an electrical phenomenon, to the suggestion that humans may be able to tap into the so-called sixth senses of animals, or that the earth’s core is made of radium and drives recurring cycles of life’s evolution, Gernsback’s purportedly “scientific” titles reveled in the extraordinary,” Wythoff writes.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1908.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1908, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: AEROCAB | LIGHT-CENTURY | LUNARSCAPE.

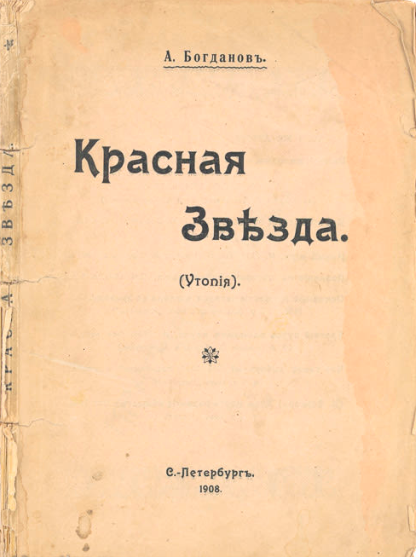

- Alexander Bogdanov’s Red Star. Leonid, a scientist-revolutionary active in the Russian Revolution of 1905, is befriended by Menni — who (spoiler alert) turns out to be a Martian in disguise. Leonid, it seems, has been selected by the Martians to visit them — which he does via the “etheroneph,” a nuclear photonic rocket. Mars, Leonid discovers, is a post-revolutionary society — an idyllic communist-ish social order boasting a planned economy and advanced cybernetic control; Martians work only as much as they want to. The “red star” also boasts nuclear fusion and propulsion, atomic weaponry, computers, blood transfusions, and (almost) unisexuality. However, the Martians have run out of resources and are considering an invasion of either Earth or Venus. Sent home after he kills one of the Martians who threaten to colonize Earth, Leonid rejoins the revolutionary struggle. Fun fact: Bogdanov (1873–1928) was one of the early organizers and prophets of the Bolshevik party; Stalin was a fan of his writing. He followed this novel with a prequel in 1913, Engineer Menni.

- Xin jiyuan’s [Bigehuan zhuren] The New Era — a late Qing proto-sf novel involving a zero-sum contest between Chinese and western culture and epistemologies, and the entanglement of different time systems. Set in 1999, it focuses on a world war between China and The West. Magic weapons such as “soul-stealing sand” (zhuihun sha) [radium?], which might seem like the remnants of Chinese novels about spirits and devils, are in fact speculative and fantastic novelties from contemporary newspaper and magazine reports introducing the latest western inventions. It’s been noted that the author’s imagination of tomorrow’s world is affected by racist discourse, and his vision unconsciously replicates the logic of colonialism.

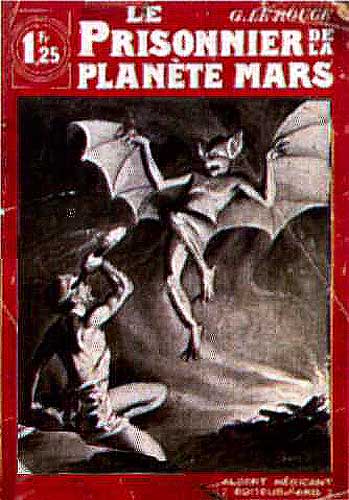

- Gustave Le Rouge’s Le Prisonnier de la Planète Mars. Amateur astronomer Robert Darvel arranges to have himself transported to Mars in a capsule propelled (how else?) by a psychic energy produced by thousands of Indian yogis gathered together as one cosmic soul. Among other observations he makes about Mars’s flora (carnivorous grass) and fauna (giant crabs, jelly-like octopi with pseudo-human faces), Darvel discovers that the planet is inhabited by dull-witted humanoids who are herded and harvested by three species of vampire creatures. The vampires are controlled by squid-like, invisible beings haunting an abandoned city. Even worse, a Great Brain, which inhabits a crystal mountain surrounded by magnetic storms, is controlling the squid-vampire creatures! Mars, it seems, is like an evil version of L. Frank Baum’s books Oz. Darvel finally returns back to Earth, with some of the invisible vampires in tow… thus setting up this book’s 1909 sequel, La Guerre des Vampires (see 1909).

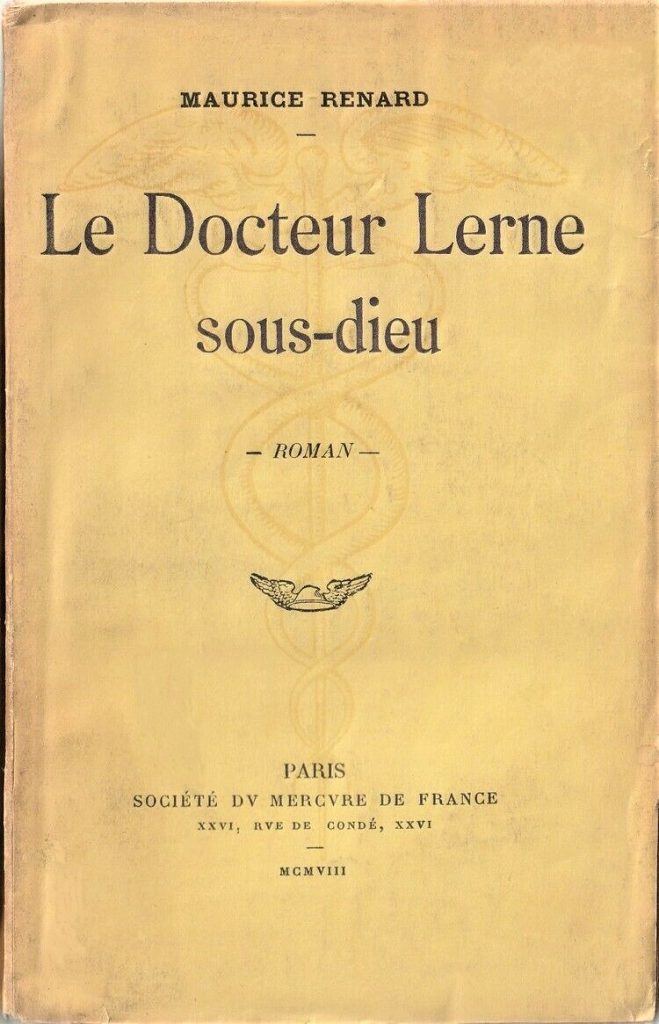

- Maurice Renard’s Le Docteur Lerne, sous-dieu (Doctor Lerne, Undergod, 1908). Returning to the castle where he grew up, after many years away, Nicolas Vermont is surprised to discover that his uncle Frédéric, a retired surgeon, is changed and hostile. Frédéric is engaged in mysterious scientific research, and forbids Nicolas access to his laboratory greenhouses; he also insists that Nicolas not court his protégée, Emma. Nicolas defies both injunctions. When Frédéric realizes that Nicolas has discovered the nature of his research — uncanny plant/animal hybrids! — he temporarily exchanges Nicolas’s brain with that of a bull. (Renard plays with mythology, in this story: the lab is a labyrinth; Nicolas’s bull-brained body is a Minotaur.) Frédéric then develops a means of projecting his own consciousness into a machine — Nicolas’s high-tech automobile. A Symbolist-ish homage to H.G. Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau, but it extrapolates the notion of biological engineering much further than Wells, all the way into the fantastic. Part of the originality of the tale is in its sf eroticism, and in how it portrays the mind-body split through narrative point of view. Its risqué subject matter and offbeat points of view make it unlike anything else in the genre until the 1960s. Fun fact: This was Renard’s first novel. The poet Apollinaire was a fan: “A little marvel of fantasy: charming, cultivated, and effortlessly learned.”

- Jules Verne’s The Chase of the Golden Meteor. One of the last novels written by Verne. The book is seen as less an example of hard science fiction than a social satire lampooning greed, monomania and vanity. It concerns the rivalry between two amateur astronomers in the same small American town who spot a new meteor and attempt to claim the credit for themselves. The meteor turns out to be made of gold and thus extremely valuable. Extensively edited by Verne’s son, Michel Verne, who is known to have introduced the character of the inventor, emphasized the romantic sub plot of this novel and expanded it from 17 to 21 chapters, among other changes. Fun fact: Seems clear to me that Hergé read this book… Other Hergé works influenced by Verne: Compare Jo, Zette and Jocko’s adventures Le “Manitoba” ne répond plus (1936) and L’éruption du Karamako (1936) vs. Verne’s Vingt mille lieues sous les mers; Tintin’s escape from the Pachamac in Le Temple du Soleil (1946-1948) vs. Ayrton’s escape from the pirate ship in Verne’s L’Île mystérieuse; Sir Francis Haddock’s destruction of The Unicorn in Le Secret de La Licorne vs. Ayrton’s destruction of the pirate ship; the last-minute rescue in L’Étoile mystérieuse vs. the finale of L’Île mystérieuse; etc.

- Willis George Emerson’s The Smoky God, or A Voyage Journey to the Inner Earth. Describes the adventures of Olaf Jansen, a Norwegian sailor who sails (with his father) through an entrance to the Earth’s interior at the North Pole. Set in 1829 in a hollow-Earth Eden on the Symmes model, where a scientifically advanced race of long-lived giants is discovered worshipping its “smoky god,” which is the interior sun. Eventually the protagonist, who has arrived via the Arctic Symmes Hole, leaves via the Antarctic, and is thought mad for many years. Fun fact: The author was a criminal entrepreneur, involved in at least one mining fraud and a stock fraud late in life, the latter involving the Emerson Motor Company (whose cars were disguised Fords).

- Randall Parrish’s Prisoners of Chance — Lost race adventure novel in which adventurers of the late 18th century encounter the remnants of the old civilization of the Mound Builders in North America.

- Frank Hatfield’s The Realm of Light. Utopian lost race novel. The Zoeians, inhabitants of a secret African country, have discovered the secrets of solar power and immortality and are evolving into a higher form of mankind.

- Nettie Parrish Martin’s A Pilgrim’s Progress in Other Worlds; Recounting the Wonderful Adventures of Ulysum Storries and His Discovery of the Lost Star ‘Eden’. Ulyssum Storries creates a “skycycle” (“a bird-like flying machine powered by electricity and capable of Space Flight”) to take him into outer space where he visits Earth’s moon, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and finally the Sun. Each world he visits has a different society, each with a unique relationship between the sexes, leading the protagonist to explore the condition of women across societies. Although the author examines women’s role in society, this is a Christian story exploring the layers and levels of Christian ideology across the extended metaphor of a solar system. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Karel Čapek (with Josef Čapek)’s “System” — humorous pseudo-sf story about an industrialist who routinizes his workers, like robots… until one of them becomes “humanized” by the sight of a woman. Čapek would be exceedingly prolific; his oeuvre includes plays, novels, stories, much journalism. After publishing several volumes of stories, he would produce the proto-sf play for which he remains best known, R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots (see 1920), and several proto-sf novels. But it all begins here.

- Ferdinand H. Grautoff’s Banzai! — First published in German in 1908; shown here is a 1909 US edition. A late but reportedly interesting treatment of the racist “yellow peril” motif. The Japanese gain supremacy in the Pacific and invade the United States.

- Jack London’s The Iron Heel. Between the (near-future) years of 1912 and 1932, according to the on-the-scene MS presented by a far-future historian, an oligarchy known to its foes as the Iron Heel arose in the United States. (We learn, from the future historian, that the Iron Heel would maintain power for 300 years until a socialist revolution finally overthrew it, ushering in a utopian future society.) The Iron Heel is composed of robber barons who have bankrupted the middle class and reduced farmers to serfdom; they use mercenaries to keep laborers — in all industries except steel, rail, and others important to the oligarchs — in check. The Iron Heel has an amazing city built — it’s called Asgard, but let’s face it, it’s Google-era San Francisco — where the proles are wowed by technological advancements but prevented from advancing into the middle class. Fun fact: Orwell hailed London as having made “a very remarkable prophecy of the rise of Fascism.” Serialized here at HILOBROW.

- Jerzy Żuławski’s Zwycięzca (The Conqueror; also translated as The Victor, 1908–1909; as a book, 1910). Sequel to 1903’s On the Silver Globe (the name of the spaceship that brought an international scientific expedition to the Moon). Zwycięzca is set seven hundred years after this original lunar expedition. Marek, a curious young man, decides to find out about the long-forgotten enterprise and goes to the Moon to be taken by the stunted and primitive descendants of the first colonist as the long-awaited messiah, the Old Man himself (the progenitor of the colony), who according to the locally dreamed up mythology left for his home planet and was supposed to return. Marek accepts the role, but fails as a savior, dies, then becomes the Conqueror/Victor, the central figure in the scripture that defines the beliefs of some of the Lunarians. All of which reminds me of the “Planet Erf” subplot of Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. Fun fact: The final installment in the trilogy is 1911’s Old Earth. Click here for more info on the trilogy.

- Maurice Baring’s “The Shadow of a Midnight.” Published in The Morning Post. Baring writes a brief vision of “Venus” in a story collected in his Orpheus in Mayfair (1909), which also contains this 1908 story about precognition. I haven’t read it; seems like it may be fantasy, not proto-sf. Fun fact: Friend of Chesterton’s.

- James Elroy Flecker’s novella The Last Generation — the end of procreation. The narrator is spirited into times moderately close to the present, where he witnesses the self-willed extinction of the human race through a refusal to breed more children. (The bearing of children is punishable by death). A satire on fin-de-siècle Decadence. The narrator is then taken much further forward, where he discovers that apes are destined to become the masters of the planet and “try again.” (Isn’t this the plot of the original novel version of Planet of the Apes?) Fun fact: The author was a playwright best known for Hassan: The Story of Hassan of Bagdad and How He Came to Make the Golden Journey to Samarkand (1922), a fantasy play that helped popularize the catch-phrase “We take the Golden Road to Samarkand.”

- Navarchus’s The World’s Awakening (1908; vt When the Great War Came 1909) by Patrick Vaux (Maclaren Mein) and Lionel Yexley [writing together as by Navarchus] places well into the future the beginning of the world conflict, this time describing a 1920s the authors feel will be won or lost at sea.

- Catherine Agnes Scrymsour Nichol’s The Mystery of the North Pole. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Carl Grunert’s Der Marsspion und andere Novellen (The Martian Spy and Other Stories). After Lasswitz, Grunert was a pioneer of German proto-sf writing. His writing was not super-interesting, however; he often merely imitated Wells or Verne. Except for the title story, which suggests that Martians have already invaded and are living among us — an original concept. Collected in The Black Mirror and Other Stories: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Germany and Austria.

- E. J. Rath’s [joint pseud. of Edith Rathbone Brainerd and Chauncey Corey Brainerd] The Sixth Speed. In the near future a disgruntled inventor applies his invention – a yacht capable of carrying a substantial cargo at 120mph indefinitely – to piracy on the high seas, but is eventually dissuaded from this course. The authors, a married couple, were killed when the roof of the Knickerbocker Theatre in Washington D.C. collapsed under the weight of heavy snow. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

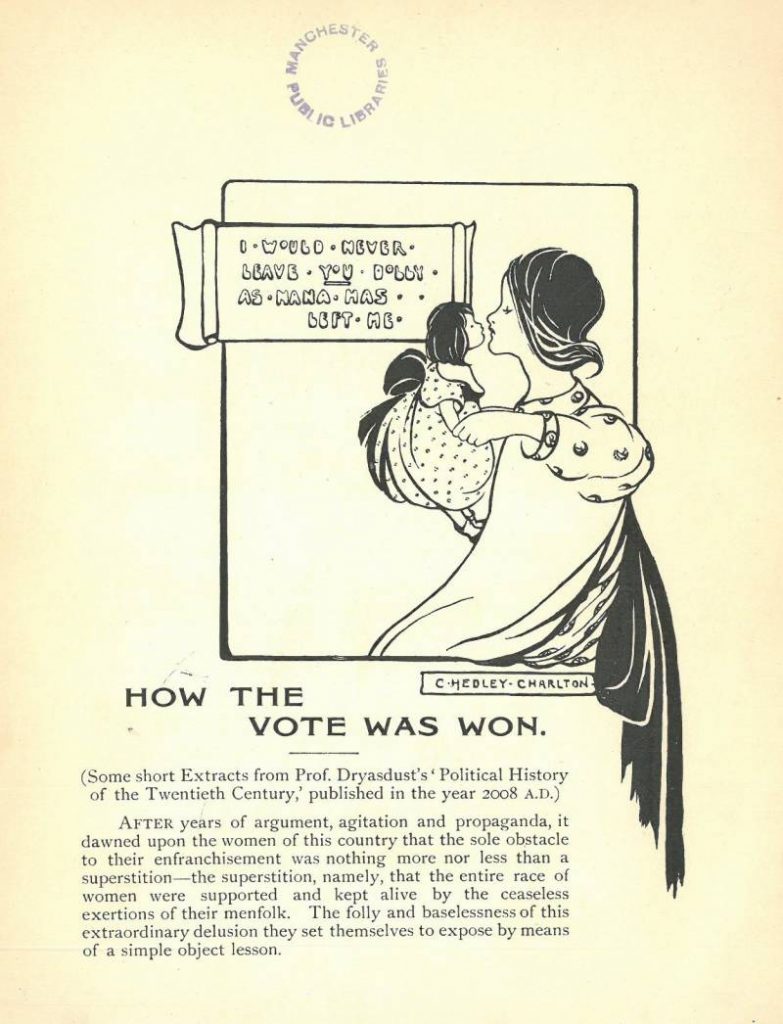

- Cicely Hamilton (Mary Cicely Hammill)’s feminist play How the Vote Was Won (1908 chapbook, first performed 1909). Written with Christopher St John (who had decades previously abandoned their birth name, Christabel Marshall). The outcome predicted by the title is achieved when those women without means go on strike. See 1922 entry for info on Hamilton’s proto-sf novel Theodore Savage.

- Raymond McDonald’s The Mad Scientist. “Imaginative, a treasure-trove of motifs, but lacking literary quality… Still, a very important work typologically.” – Bleiler.

- Edith Nesbit’s “The Third Drug” — a mad scientist tries to infect his involuntary subject with an agent that will transform him into a superman. Serialized at HILOBROW in 2021. Will be reissued by MIT Press as part of the collection More Voices from the Radium Age.

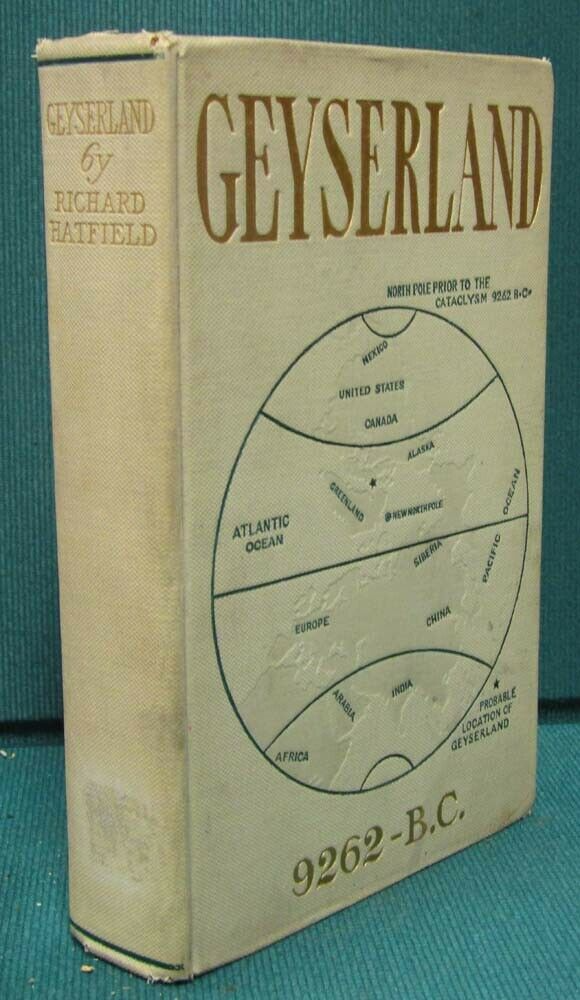

- Richard Hatfield’s Geyserland: Empiricisms in Social Reform: Being Data and Observations Recorded by the Late Mark Stubble, MD, PhD: (A Tentative Edition). A Lost Race tale in which Mark Stubble discovers a 17th-century manuscript suggesting that a shifting of Earth’s axis in 9262 BCE doomed various species to extinction, and trapped the citizens of Geyserland in the Arctic near Greenland. When the land is rediscovered by “Adam Mann” in the 17th century, though, his love affair with “Evrona” is doomed. Sounds cliched and silly… but I dig the book’s cover.

- H.G. Wells’ The War in the Air (serialized 1908 in The Pall Mall Magazine). After Bert Smallways, a forward-thinking bicycle mechanic, is accidentally carried off in a hot air balloon belonging to Mr. Butteridge, inventor of a revolutionary maneuverable aircraft, he is shot down in Germany. Prince Karl Albert, who has organized an air-ship attack on the Eastern United States, takes Smallways along for the invasion — since he believes him to be Butteridge. (Simultaneously, the Confederation of Eastern Asia — China and Japan — launches an aerial attack on the Western United States.) Smallways looks on in horror as an American naval fleet is obliterated by German aerial bombardment; soon after, German air ships rain destruction on New York City. However, not long after this, German air fleet is attacked by the Confederation, whose one-man flying machines firing incendiary bullets overpower the hydrogen-filled zeppelins. Can Bert turn the tide of battle by helping America to develop Butteridge’s aircraft? Will the entire “fabric of civilization” (the late-period Wells is over-fond of such formulations) be torn asunder, and England revert to a medieval social order? Fun fact: Written in four months.

- Hilaire Belloc’s Mr Clutterbuck’s Election. The French-born author, in UK from an early age, was known for his poetry, notably The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts (1896), plus his many ballades successfully adopting the medieval French form; for his anti-Semitism (he never abandoned his belief in the guilt of Dreyfus); and for his Roman Catholic apologetics — he was bosom buddies with Chesterton. He was a disputatious Liberal MP from 1906-1910, and wrote several proto-sf works to argue his points. With A Change in the Cabinet (1909) and Pongo and the Bull (1910), this book makes up a near-future assault on Edwardian UK politics. SFE: “Packed with energy though formally negligent, Belloc’s fiction awaits the modest revival due it.”

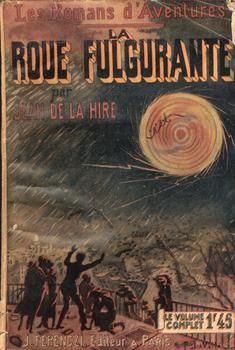

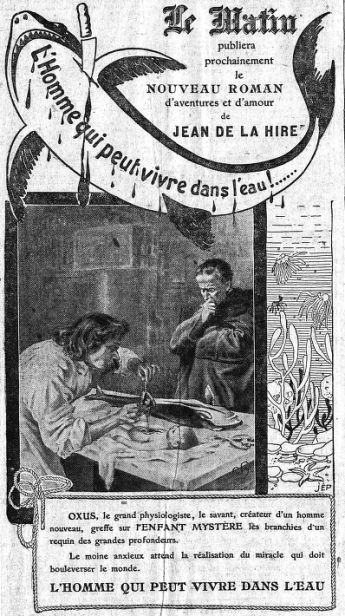

- Jean de la Hire’s La roué fulgurante (The Fiery Wheel). The author’s first science fiction novel was very successful; Stableford claims it to be the first story of alien abduction. The abductors travel through the solar system in what is remarkably like a flying saucer. Fun facts: De la Hire was rhe pseudonym of French author Adolphe d’Espie (1878-1956) who began his prolific career before 1900, publishing mainly as by La Hire, though he also wrote under the monikers Commandant Cazal, Edmond Cazal, André Laumière, Arsène Lefort, John Vinegrower and Alexandre Zorka. La Hire remains best known for the Nyctalope sequence (see below).

- Jean de La Hire’s Nyctalope series begins in 1908 with L’Homme Qui Peut Vivre dans l’Eau (The Man Who Could Live Underwater). The Nyctalope, who does not actually appear in this book, is one of the first literary superheroes of pulp fiction. Leo Saint-Clair is a kind of cyborg, boasting an artificial heart, night vision, and other artificially enhanced senses. The Nyctalope’s foes include mad scientists, potential dictators of the world, and the occasional alien. Here in The Man Who Could Live Underwater, we meet a previous member of the Saint-Clair family, Jean, later identified as Leo’s father. Fun facts: During his lifetime, De la Hire authored more than 300 novels and short-stories, some published with more than 100,000 issues, the most popular being his super-science works – and among them the Nyctalope series. His pro-German writings during World War Two ended in his imprisonment.

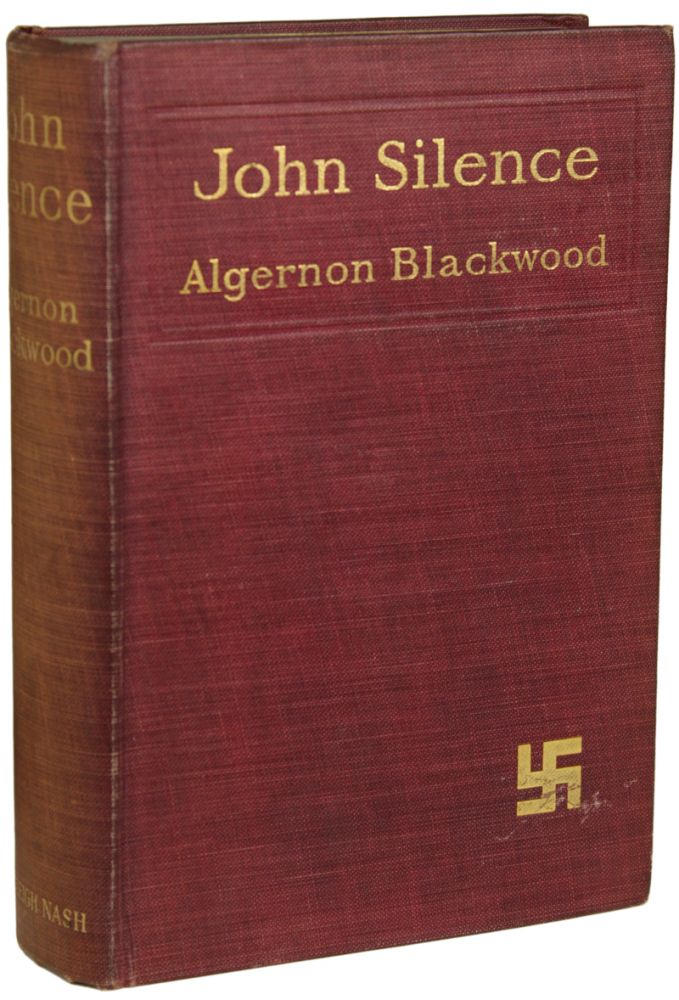

- Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence collection. Occult detective. Includes “A Psychical Invasion” (a humor writer named Pender, experimenting with hashish, has contacted some evil force in his home), “Ancient Sorceries” (cat folk inhabit a sleepy English village), “Secret Worship” (a school in a German town recruits human sacrifices from among its former students), “The Camp of the Dog” (lycanthropy is explained as a psychic body that detaches from the physical body of a psychologically conflicted/repressed person), and “The Nemesis of Fire” (a Holmesian framework, in which Silence and Hubbard are invited out to the Manor House of Colonel Horace Wragge, a man of action who is sorely tested by the strange occurrences that have affected his family). Blackwood created his investigator more by accident than intention when he approached his publisher in 1908 about a collection of stories about “psychic” phenomenon. The bookseller suggested that the book might do better if it were tied together by a central character. Silence would prove to be the most influential fictional detective to take on the paranormal. See 1914 for the final John Silence story, “A Victim of Higher Space.” Fun fact: “Aside from Poe, I think Algernon Blackwood touches me most closely—& this in spite of the oceans of unrelieved puerility which he so frequently pours forth. I am dogmatic enough to call The Willows the finest weird story I have ever read, & I find in the Incredible Adventures & John Silence material a serious & sympathetic understanding of the human illusion-weaving process which makes Blackwood rate far higher as a creative artist than many another craftsman of mountainously superior word-mastery & general technical ability…” (HP Lovecraft to Vincent Starrett, 6 December 1927).

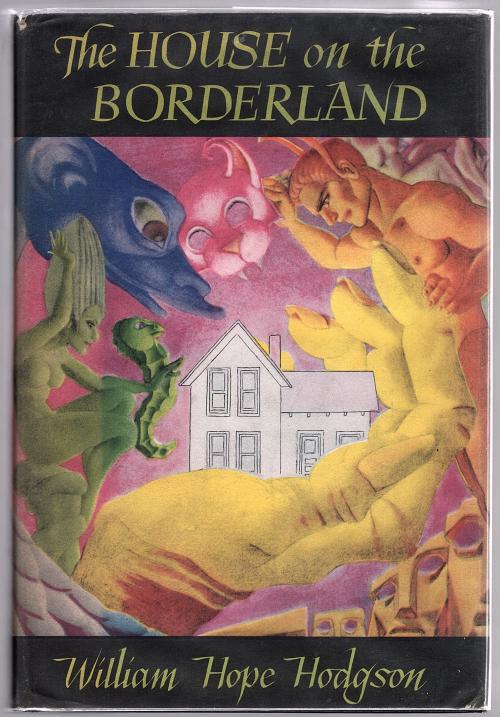

- William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland: From the Manuscript, discovered in 1877 by Messrs Tonnison and Berreggnog, in the Ruins that lie to the South of the Village of Kraighten, in the West of Ireland Set out here, with Notes. Directly over a vast chasm near a remote Irish village, some two hundred years before our narrative begins, someone has built a weird stone house — circular, with “little curved towers and pinnacles, with outlines suggestive of leaping flames.” As our narrator — the Recluse, whose journal it is that we’re reading — soon discovers, the house is a space/time portal. He’s oppressed by a hallucinatory vision, in which he travels to another planet (or dimension) where he finds a version of the house; and he’s attacked by humanoid “swine-things,” who emerge from the chasm. The house also transports the recluse to “the Sea of Sleep,” where he reunites with his lost love — who warns him that the house was “founded on grim arcane laws.” The man is afforded a cosmic vision of Earth passing through eons to its destruction… and he’s infected by a luminous fungus! A pioneering weird fiction horror story — and if the house co-exists in two worlds/dimensions, and if the “swine-things” are monsters from a parallel world, then this must also be seen as a pioneering example of horror in sf. Fun fact: Hodgson’s strain of cosmic horror would prove influential on the likes of H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith.

- Samuel Hopkins Adams’s The Flying Death — an “impossible crime” tale in which a prehistoric flying reptile terrorizes Long Island.

- L.P. Gratacap, The Evacuation of England. Gratacap was a US naturalist, museum curator and author. (See 1903.) This novel pins its expectations of disaster on the completion of the Panama Canal, which causes Central America to sink and Atlantic currents to flow westwards. The SFE says: “The science is foolish, but the climatic changes it depicts now seem less improbable.”

- John Davidson’s The Testament of John Davidson. Third in a series of book-length poems — which includes The Testament of a Man Forbid and The Testament of a Vivisector (both 1901), The Testament of an Empire Builder (1902). These Testaments are philosophical and rhetorical exercises as much as poetry; they express Davidson’s atheism, interest in Nietzscheism, and his commitment to materialism. In this and the other two of the first three installments, one reads in the SFE, “the cosmological sublime soars rather beyond the Nietzschean.” Davidson intended to produce a long series of Testaments which would include ‘The Harlot’, ‘The Artist’, ‘The Christian’, ‘The Criminal’ ‘The Mendicant’, ‘The Evolutionist’, ‘The Proletarian’ and ‘The Deliverer’. However, his books did not sell well. He killed himself in 1909.

- Segundo de Chomón’s proto-sf film El hotel eléctrico (Spain). Laure and Bertrand arrive at the Electric Hotel, where a control board allows inanimate objects to come to life. For most of the film, the effects are used to perform tasks such as polishing shoes, styling hair and putting away luggage, to the two guests’ great pleasure. At the end, a drunken concierge erratically throws switches that cause the system to go haywire, sending all of the hotel’s furniture into a jumbled, chaotic mess. A very early example of stop-motion animation.

- Roy Rockwood’s Five Thousand Miles Underground. Roy Rockwood was a house name used on juvenile series published by several firms; all titles from 1906 onwards were generated by The Stratemeyer Syndicate. The best of the Roy Rockwood titles are reportedly the first volumes in the Great Marvel sequence, written by Howard R Garis: Through the Air to the North Pole (1906), Under the Ocean to the South Pole (1907), Five Thousand Miles Underground, Through Space To Mars (1910), and Lost On The Moon (1911)

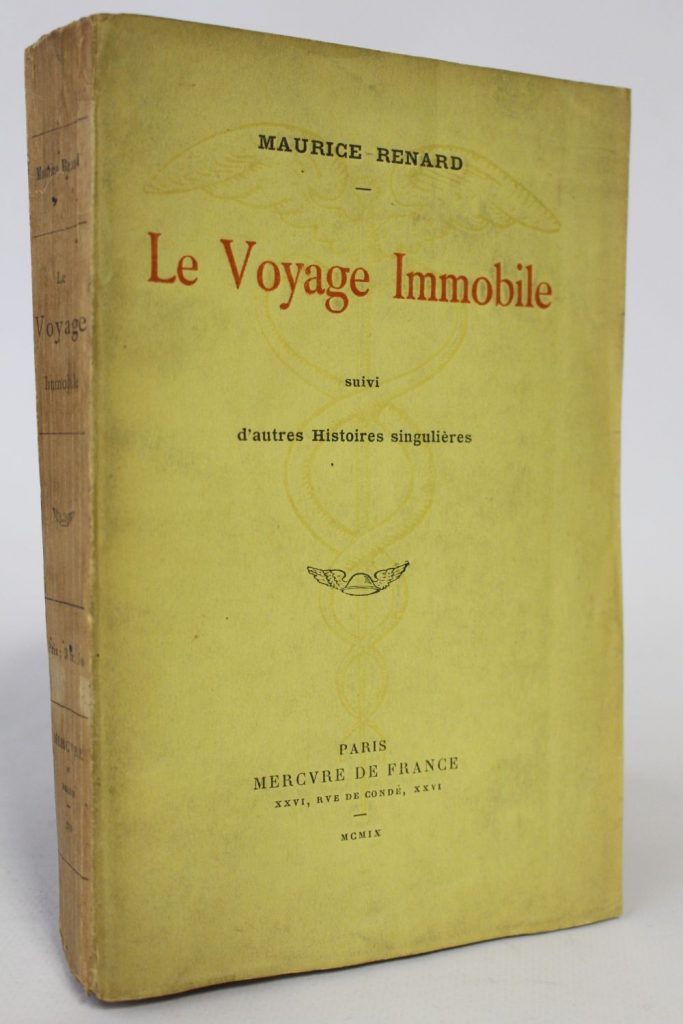

- Maurice Renard’s story collection Le Voyage immobile suive d’autres histories singulieres. The title novella proposes an experimental anti-gravity flying machine called an “aérofixe” which, by remaining stationary in the sky, “moves” from one location to another as the Earth spins below it. Detrimental to its passengers. There is a 1922 revised edition of the collection too.

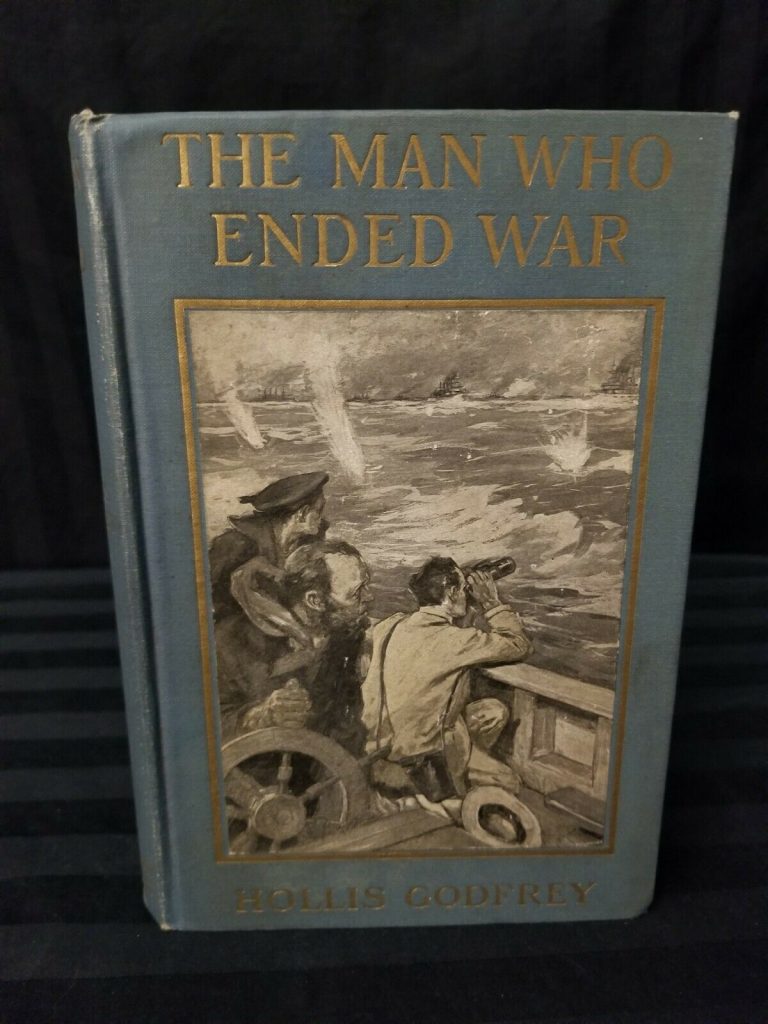

- Hollis Godfrey’s The Man Who Ended War. The Secretary of War of the United States receives a letter sent to his and all other nations, declaring that war has too long devastated the earth and the time has come for peace. It orders them to destroy their weapons of warfare and disband their militaries. The letter ends: “One year from this date will I allow for disarmament and no more. At the end of that time, if no heed has been paid to my injunction, I will destroy, in rapid succession, every battleship in the world. By the happenings of the next two months you shall know that my words are the words of truth.” It is signed “The man who will stop all war.”

- Jack London’s “The Enemy of All the World” (October 1908 Redbook) – a lone genius invents a super-weapon and terrorizes the world.

- Jack London’s “A Curious Fragment” (10 December 1908 Town Topics), set in the twenty-eighth century, shows one of the ruling oligarchs encountering a severed arm bearing a petition from his industrial slaves. Like several other of London’s sf works, it deals with the struggle between the capitalist class, trying to establish a fascist oligarchy, and the proletariat, striving for socialism.

- Gernsback’s essays “The Dynamophone”, “The Aerophone Number”, and “The Wireless Joker” appear in Modern Electrics in 1908.

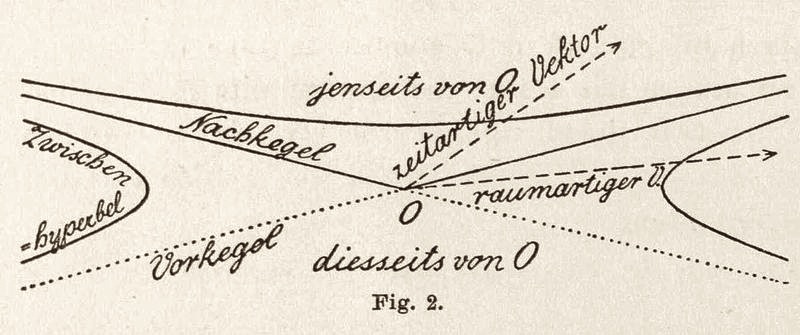

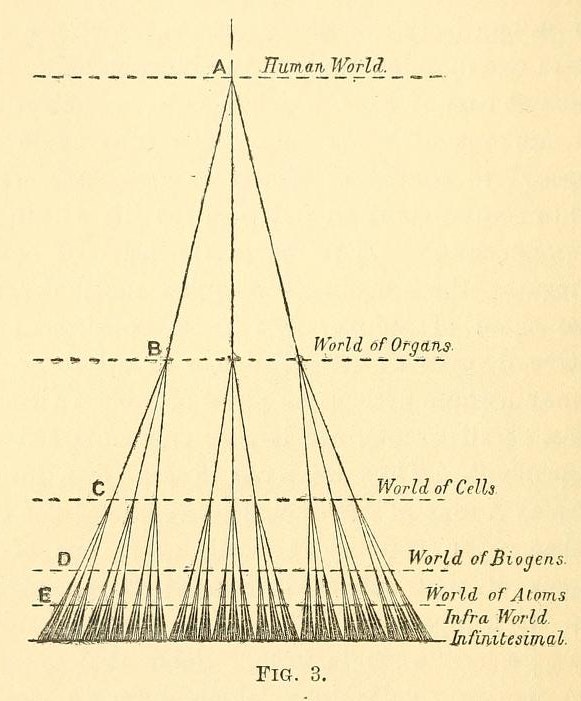

ALSO: Minkowski — building on Poincaré’s breakthroughs — formulates a four-dimensional geometry (diagram above), allowing work in the theory of relativity to be transformed into work on the geometry of spacetime; note that his theory will not reach the general public until after WWI. Poincaré gives a talk about his observations of his own (intuitive, highly visual) thinking at the Institute of General Psychology in Paris; he’d insist that logic was not a way to invent but merely a way to structure ideas — and that logic limits ideas. King Carlos I of Portugal assassinated; Taft elected US president. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, Forster’s A Room with a View, Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, Stein’s Three Lives. Kafka begins publishing. Sorel’s Reflections on Violence (Nietzsche- and Bergson-inspired theory of revolutionary syndicalism), developing the implicit ethical and political implications of Bergson’s philosophy. Simmel’s Sociology (probes into the lived experiences of people in light of fundamental capitalist processes). posthumous publication of Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo. Bakelite (the first synthetic plastic) invented; the first steel and glass building (Berlin); Henry Ford develops the assembly line method of automobile manufacturing and produces the first Model T automobile. Matisse coins the term “Cubism.”

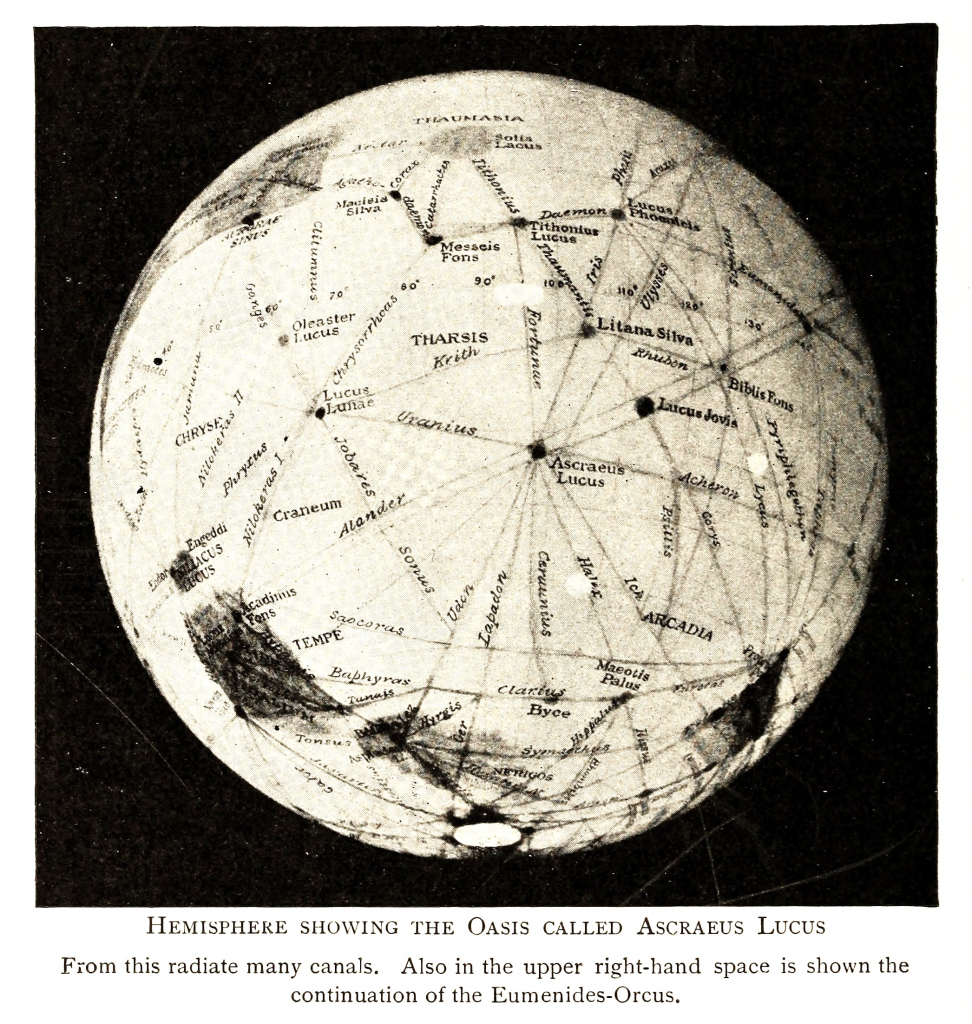

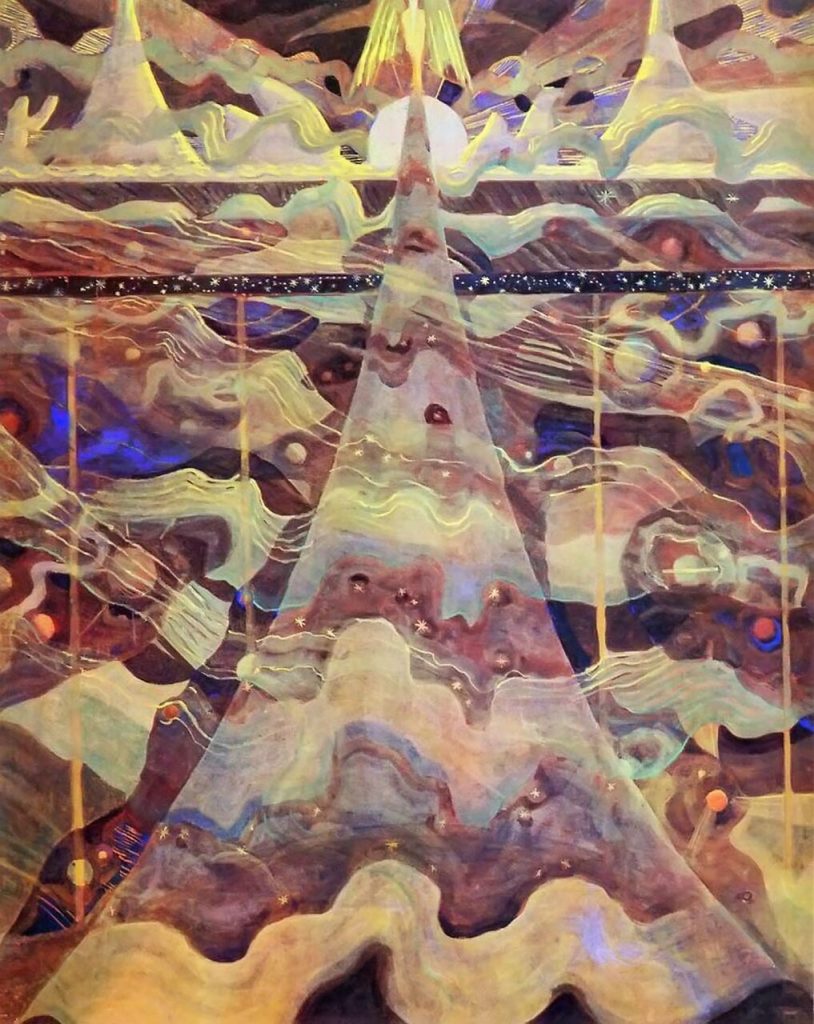

Percival Lowell’s Mars as the Abode of Life (1908; see image above). See 1906 for more info on Lowell’s conjectures, which were highly influential on proto-sf of the era.

Abstract art—painting and sculpture that makes no direct, immediately discernible reference to recognizable objects—was born of an alliance of modernist aesthetics and the occult doctrines of theosophy around this time. Its first masterworks were produced by Kandinsky in Germany, Mondrian in the Netherlands, and Kazimir Malevich in Russia; unknown to the wider world, Hilma af Klint had already begun to produce abstract art. In 1908 Kandinsky bought a copy of Thought-Forms by Besant and Leadbeater. In 1909 he joined the Theosophical Society. The Blue Mountain (1908–1909) was painted at this time, demonstrating Kandinsky’s trend toward abstraction.

The Irish physicist Edmund Edward Fournier d’Albe expanded on the views expressed in his 1907 book On the Threshold of the Unseen in New Light on Immortality (1908), where he tried to come to terms with what the notion of a human soul could mean in the atomic age. To pronounce on immortality, he said, who now was better placed than the physicist, who understood the most about energy and matter? He supposed that what we call the soul might be a real substance, albeit more tenuous than vapour, composed of particles called “psychomeres” that possess a kind of intelligence and ability to act together via telepathic contact. More info here.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin