RADIUM AGE: 1928

By:

October 31, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the years 1928–1929 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Teens (1924–1933).

Victor Gollancz founds Victor Gollancz Ltd, which publishes science fiction from its very first year onward. One of his inaugural books was Wells’s The Open Conspiracy (1928), and within a year he was publishing reissues of several works by M.P. Shiel and a new novel by E H Visiak. In the 1930s came Charles Fort’s Lo!, the first translation of Franz Kafka’s Der Prozess (written 1914-1915; 1925), sf novels by Murray Constantine (Katharine Burdekin), Andrew Marvell, Joseph O’Neill, R C Sherriff, Francis Stuart and others, and five novels by Charles Williams.

Sam Moskowitz has argued that the inspiring wonder of the galaxy was not realized until E.E. “Doc” Smith popularized the space opera — beginning with The Skylark of Space (1928). However, Mike Ashley says it was downhill from here. After the success of Skylark, sf was dragged down to its nadir — giving this era its bad reputation. In his Time Machines, Ashley says 1928 marks the beginning of a phase for sf in which Gernsbackian sf gives way to space opera and “hero sf.”

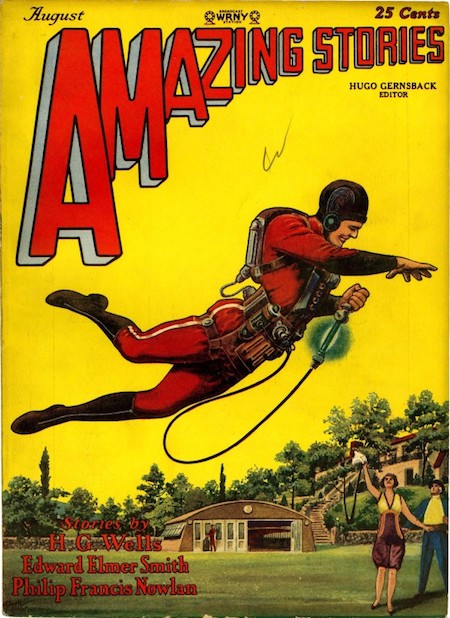

Excerpt from Hugo Gernsback’s editor’s note to the August 1928 issue of Amazing Stories:

When it comes to matter, we know nothing at all about it. It is a great unknown to us. Some scientists hold that matter is only another word for force and energy, but these, at best, are only meaningless terms — a handle for our ignorance. We look at the simplest of plants; a blade of grass that we see grow, and no scientist in the whole world can tell you exactly what makes it grow, and why it does grow, and why it is alive in comparison to the pebble, which is dead and lifeless. I need hardly touch upon the unknown properties of life, which have puzzled humanity ever since the dawn of reasoning. We have not the slightest conception just what life is ; what it is composed of, andwhat the mysterious forces are that distinguish life from lifeless matter.

Copyrighted works from 1928 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2024. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1928, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: EARTHBOUND | FANMAG | FASTER THAN LIGHT | FLOATER (a vehicle or device powered by antigravity; (specif.) an antigravity platform that flies relatively close to the ground) | GATEWAY (a portal allowing travel or communication between dimensions, alternate universes, etc.) | HYPERSPACE (a dimension or other theoretical region that coexists with our own but typically has different physical laws, esp. such a region that allows an object to travel through it such that the total journey occurs at faster-than-light speeds; cf. hyperdrive) | LUNITE | MOTHERWORLD | ROBOTIC (of the nature of a robot; of or relating to robots) | ROCKETEER | SPACE LANE (an established route through space) | SPACE NAVIGATION | SPACE TRAVELLER | SUPER-SCIENTIST (a person who studies, or creates inventions using, superscience) | ULTRAPHONE (a communications device that transmits messages faster than the speed of light) | VIDEOPHONE | VIEWPLATE.

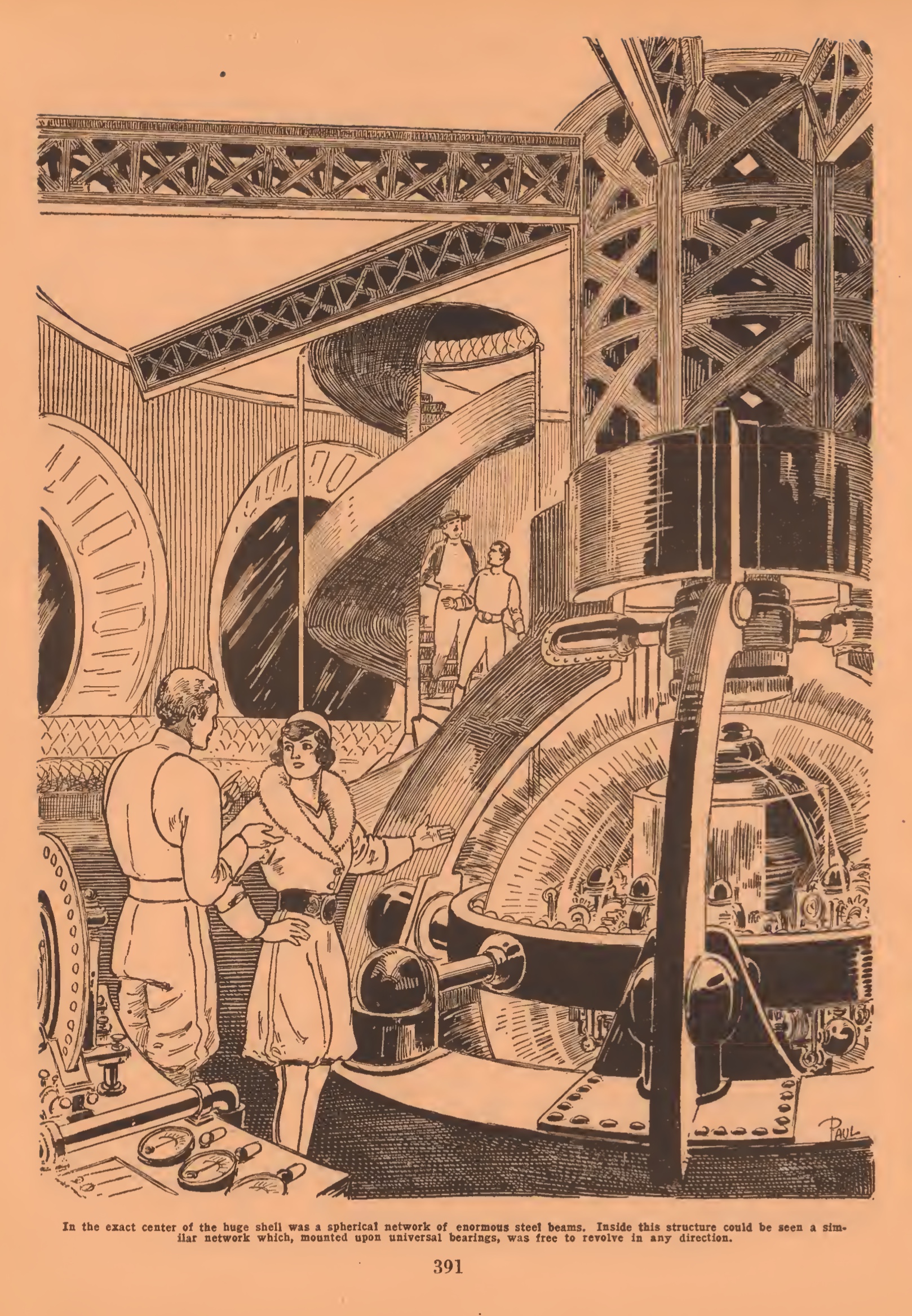

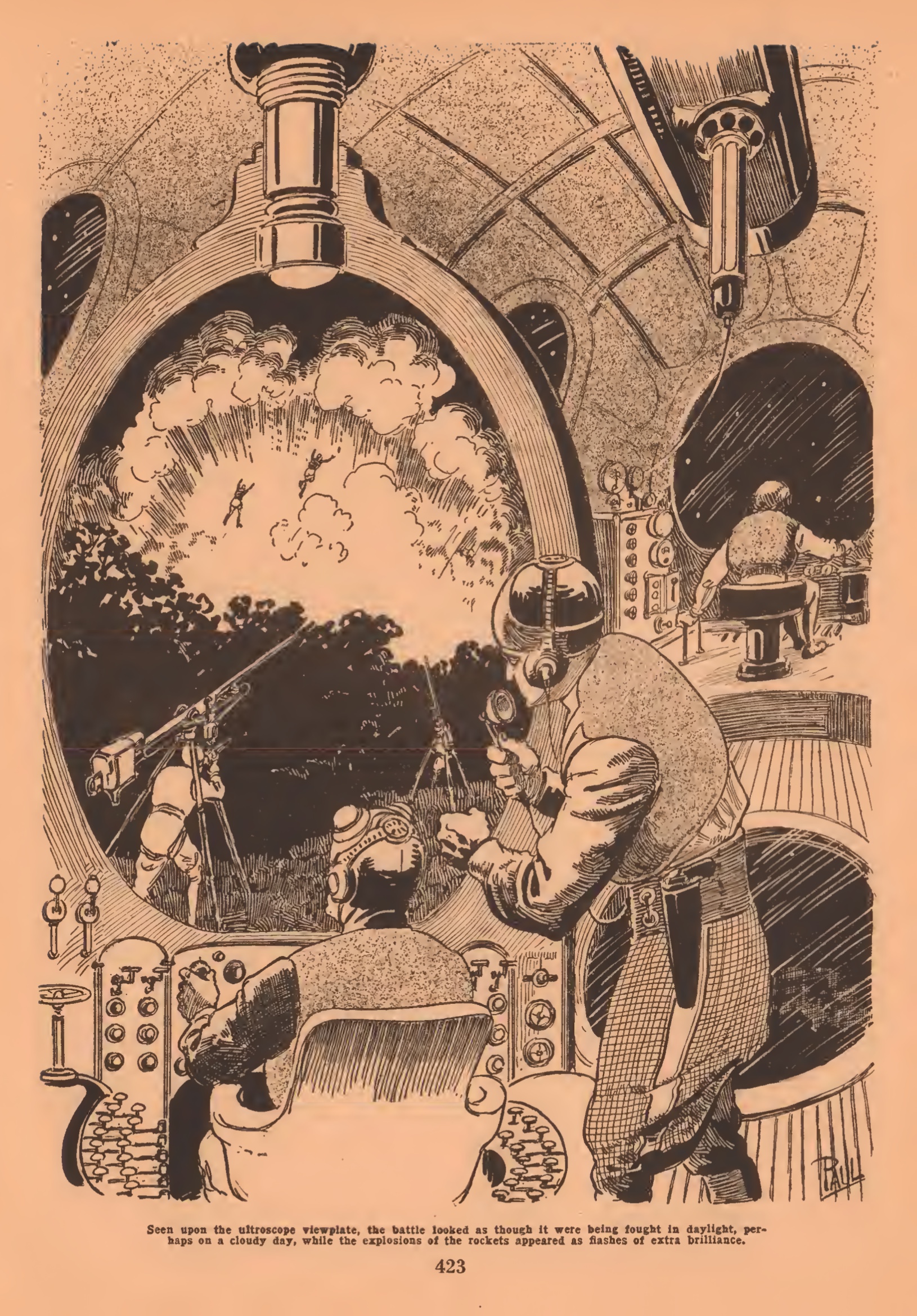

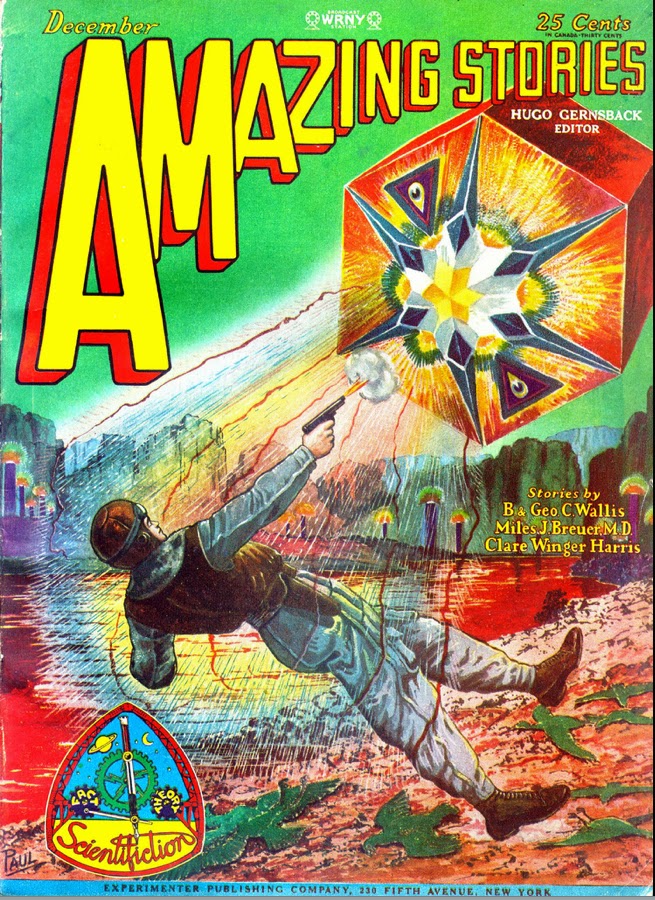

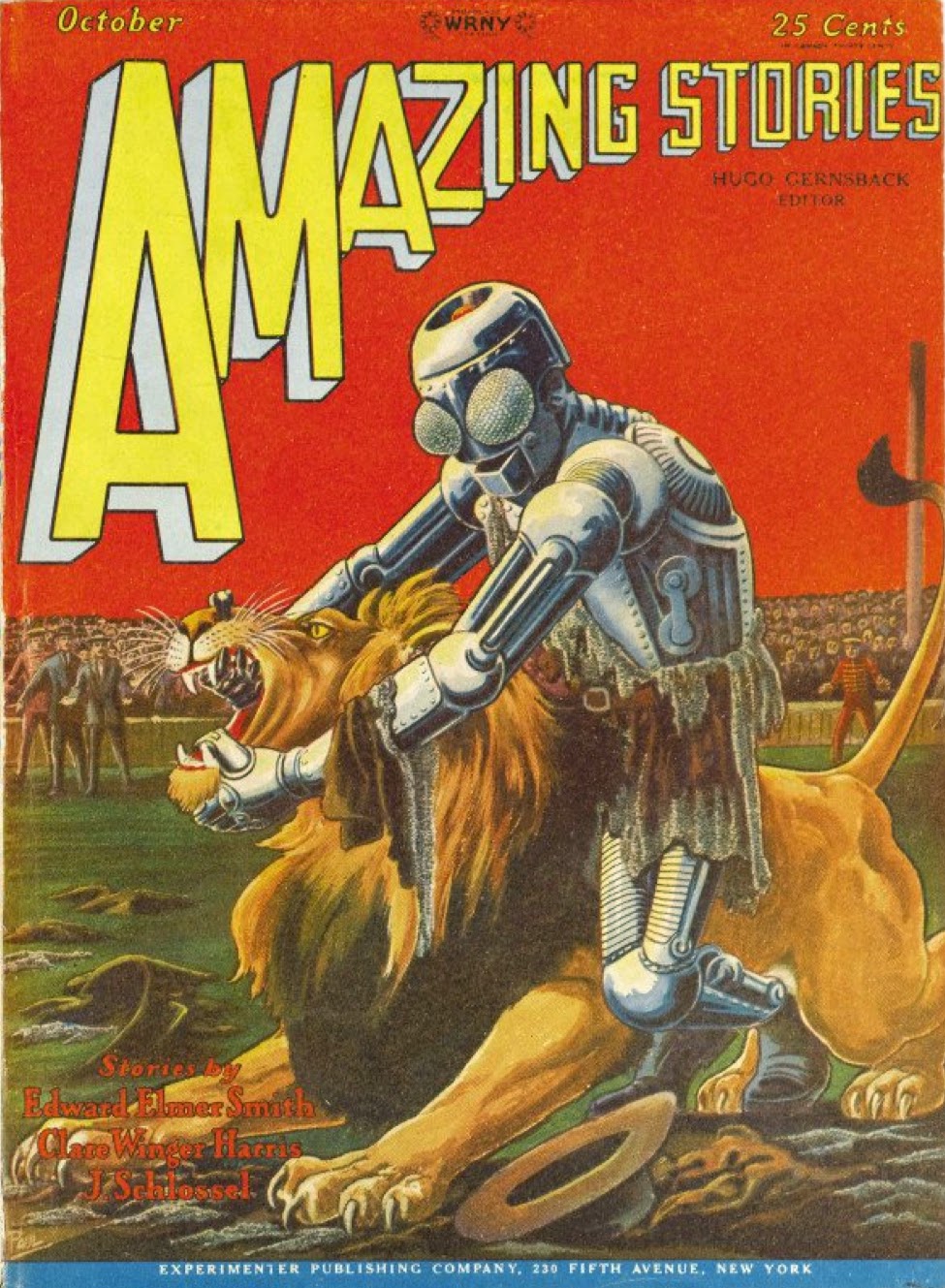

- E.E. “Doc” Smith and Lee Hawkins Garby’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Skylark of Space. Published in three installments, beginning with August 1928 Amazing Stories. Revised, in book form, as The Skylark of Space: The Tale of the First Interstellar Cruise (1946). One of the first — and, according to some Doc Smith fans, the best — space operas ever written. When scientist Dick Seaton discovers a faster-than-light fuel that will power his interstellar spaceship, The Skylark (a forty-foot sphere), his fiancée and friends are kidnapped by Marc DuQuesne and the World Steel Corporation. Although quaint by modern standards, Smith and Garby’s vision of the future — and future technology, enabling a cosmic voyage — is visionary and creative. More importantly, Smith knows how to write a yarn that, although bloodthirsty and not particularly sophisticated, is a fun, fast-paced combination of spy thriller and western. In the end, Seaton navigates the Skylark through dangers, explores strange new solar systems, rescues his loved ones, and outmaneuvers and outguns his rival, the oddly compelling DuQuesne. Fun fact: Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination. Smith would go on to write several more Skylark stories, as well as the enduringly popular Lensman space-opera series. That’s Dick Seaton on the cover of Amazing (August 1928), above. Fun facts: Among the most popular of all interwar sf tales. After Skylark the “super-science extravaganza” took over. Lee Hawkins Garby (1892–1953) was the wife of Dr. Carl DeWitt Garby, a friend of Smith’s from college at the University of Idaho. Garby is acknowledged in some circles as an early female writer of science fiction, but little is known of her life and she made no known contributions to the field beyond her involvement with Skylark.

- Philip Francis Nowlan’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Armageddon 2419 A.D. (1928). Nowlan’s novella first appeared in the August 1928 issue of Amazing Stories (the same issue which launched E.E. “Doc” Smith’s serial The Skylark of Space). In it, 29-year-old WWI vet and mining engineer Anthony Rogers falls into a state of suspended animation (in the year 1927), then wakes up five hundred years later. He discovers an America that for the past three centuries has been a backward province of the globe-spanning, part-Mongolian part-alien Han Empire. Taken in by a gang of American rebels, he becomes a freedom fighter in the Second War of Independence. A sequel, The Airlords of Han, was published in March 1929. Fun fact: Nowlan’s long-running and much-imitated Buck Rogers comic strip, illustrated by Dick Calkins, first appeared in January 1929. The protagonist was renamed in imitation of the popular cowboy actor Buck Jones. The original novella was serialized here at HILOBROW. Fun fact: “Buck Rogers stuff” would become a synonym for “low-grade sf.”

- Edmond Hamilton’s “Crashing Suns.” Hamilton’s importance to sf was signaled with the publication of “Crashing Suns” (August-September 1928 Weird Tales), one of the founding texts of the kind of space opera with which he soon became identified: a universe-spanning tale, often featuring in early years an Earthman and his comrades (not necessarily human) who discover a cosmic threat to the home galaxy and successfully – either alone, or with the aid of a space armada, or both – combat the aliens responsible for the threat. Though not technically part of the series, “Crashing Suns” is closely linked to the six Tales of the Interstellar Patrol stories, which followed over the next two years.

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu” in Weird Tales. “He said that the geometry of the dream-place he saw was abnormal, non-Euclidean, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours.”

- Francis Flagg’s “The Blue Dimension” (Amazing Stories, June 1928). Doctor Crewe and his assistant, Robert, pierce the veil between our world and that of a higher vibration that they call the Blue Dimension. They are able to observe this parallel world with a new invention, special glasses. Crewe builds a machine that can send things into the other dimension. Lovecraftian chills and thrills.

- Alexander Romanovich Belyaev’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Amphibian Man (1928; Человек-амфибия, also known as The Amphibian). In order to save his son’s life, Salvator, an Argentinean maverick surgeon and scientist, transplants a set of shark’s gills onto the boy. Although the experiment is a success, Ichthyander — like Aquaman, say, or the Boy in the Plastic Bubble — can no longer interact normally with humankind. He spends most of his time in the ocean, diving. A local pearl harvester, Pedro, who captures the fabled “Sea Devil” of La Plata Bay, attempts to exploit Ichthyander’s abilities — but the boy is more concerned with improving living conditions for the world’s poor than in helping one capitalist get richer. Possibly inspired by Jean de La Hire’s 1909 sci-fi novel The Man Who Could Live In Water. His work has Vernean enthusiasm but his characters are wooden. Fun fact: Alexander Belyaev, “Russia’s Jules Verne,” died of starvation in 1942 when his town was occupied by German troops. The 1962 musical film adaptation of the book, directed by Vladimir Chebotaryov, was a huge success in the USSR. Featuring a cast of beautiful young actors, the film’s theme song, “The Sea Devil,” became a hit that was played well into the 1990s. It inspired a 2004 TV series, as well as a mid-1960s experiment in living underwater, which was named The Ichthyander Project.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure When the World Screamed (1928). Narrated by a drilling engineer, the fifth and final Professor Challenger adventure takes us not outward (e.g., to a South American plateau crawling with dinosaurs), nor inward (e.g., to an airtight chamber, while the Earth passes through a poison belt), but instead downward. Challenger, here described as “a primitive cave-man in a lounge suit,” while also “the greatest brain in Europe,” proposes to drill his way from a tract of land in Sussex (England) eight miles beneath the planet’s epidermis. Why? In order to prove his hypothesis that the world is itself a living organism. In the end, Challenger becomes “the first man of all men whom Mother Earth had been compelled to recognize.” A novella, rather than a full-length novel, like all of the Challenger books the author’s goal — in addition to entertaining — is to demonstrate the superiority of abductive (logical yet intuitive) to inductive (purely scientific) reasoning. Fun fact: Some historians of science note that Doyle here challenges both the disregard for ecological thinking in his own time, and the role scientists play in the changing relationship of humankind to nature. Serialized here at HILOBROW.

- John Martin Leahy’s “In Amundsen’s Tent” published in Weird Tales. One of the best-known Antarctic stories of the era (along with Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness and John Campbell Jr./Don A. Stuart’s “Who Goes There?”). As Elizabeth Leane notes in “Locating the Thing: The Antarctic as Alien Space in John W. Campbell’s ‘Who Goes There?’, the Antarctic was a popular setting for eerie pulp stories because its landscape was perceived as not only hostile, unearthly, and surreal (as with the Arctic) but also (unlike the Arctic) remote, antipodean, and uninhabited. Although the heroic era of Antarctic exploration was underway — Scott, Amundsen, Shackleton, Mawson — large areas of the Antarctic remained unknown and unmapped. Leane argues that the Antarctic isn’t merely a setting, in many pulp stories of the era, but an integral element of the stories’ meaning. Because the Antarctic was perceived as a shapeshifting, engulfing, threatening body — like the alien in Campbell’s story. See 1912 for more on Leane’s Antarctic hypothesis.

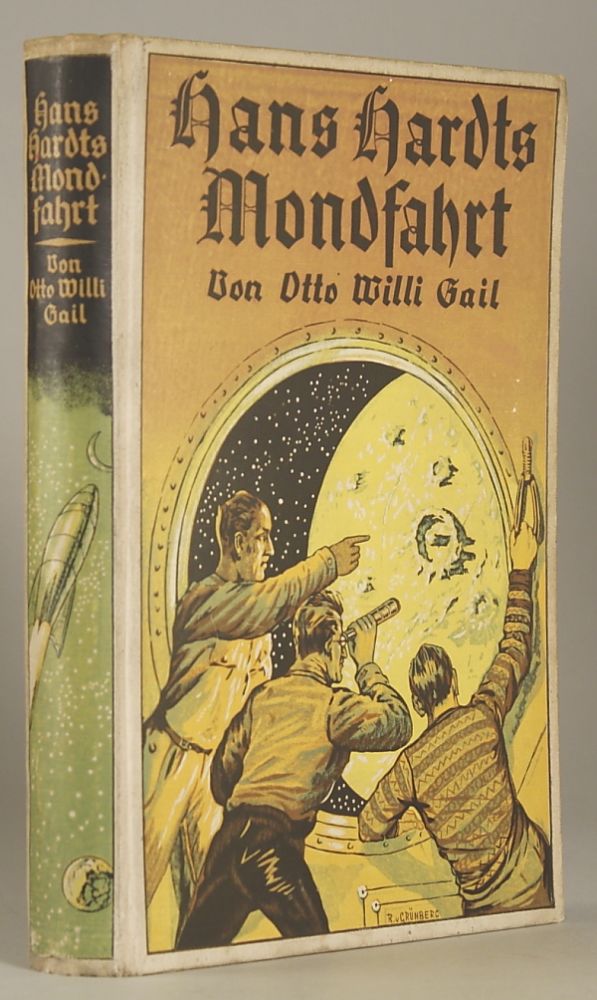

- Otto Willi Gail’s Hans Hardts Mondfahrt. A story about a trip to the moon intended to educate young men about the problems and potential of rocket flight. Later editions were revised by the author. The novel was translated into English as BY ROCKET TO THE MOON: THE STORY OF HANS HARDT’S MIRACULOUS FLIGHT (1931). “Boys’ book, fairly realistic in its description of the first flight into space … Despite Atlantis and life on the moon, the author has very carefully used the best scientific and technological data of his day, and much of what he says seems very modern. Successful as a boys’ book.” – Bleiler.

- W B Drayton Henderson’s poem The New Argonautica is of sf interest.

- Mary Borden’s Jehovah’s Day. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Alice Campbell’s The Juggernaut. First appeared serially in Pall Mall Magazine [Britain], 1927-1928. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- E.V. Gazella’s The Blessing of Azar, A Tale of Dreams and Truth. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Effie Woodward Merriman’s Rejuvenated. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Harry Stephen Keeler’s Sing Sing Nights (1928). Though primarily a suspense thriller, it features the transplant of a human brain into the skull of a gorilla

- Maurice Renard’s Un Homme chez les microbes (A Man Among the Microbes). A witty sf novel that predates by almost three decades Richard Matheson’s more celebrated The Shrinking Man. Although not the first to make use of this traditional sf theme, Renard quite well in combining the lighthearted tone of early imaginary voyage and plurality-of-worlds narratives with the realistic observations of more modern fictional variants. One witnesses vestiges of the former, for example, in a visit to the invisible utopian realm of Ourrh (with the requisite “estranging” descriptions of the life and customs of its antennaed inhabitants) and in the large doses of tongue-in-cheek humor that are present in the text. Of the latter, one witnesses such elements as detailed portrayals of altered perceptions during the shrinking process itself (gigantic house furniture, being stalked by the family cat, etc.), fears of the unknown, and various scientific observations. A quintessentially surrealistic conclusion.

- S. Fowler Wright’s The Island of Captain Sparrow. Deliberately recalls Wells’s The Island of Dr Moreau (1896) in its image of an island inhabited by satyr-like beast-men who are prey to the corrupt descendants of castaway pirates. Features as well a feral girl, the first of several similar figures used by Wright to celebrate the state of Nature in opposition to the brutality of “civilized” men.

- Otfrid von Hanstein’s Elektropolis. A mechanized city is built by Germans in the arid Australian interior. The great city of Elektropolis rises out of the wasteland and rainmaking machinery is used to create cropland to feed the immigrants from Germany. The success of this project provokes the Australian government which revokes the colonist’s land rights and war breaks out. The city’s defenses thwart the Australians who finally give up their attempt to take it over. After five years the German colony is firmly established and the desert blooms. “… interesting for its extreme faith in technology and technocracy” – Bleiler. First published in English in WONDER STORIES QUARTERLY, Summer 1930.

- David H. Keller’s “A Biological Experiment.” Everyone is sterile — but the urge for parenthood still exists.

- L de Giberne Sieveking’s Stampede! Illustrations by G. K. Chesterton. Science fiction thriller and political satire centering on the consequences of the invention of a device that can record or transmit thought and a device that uses colored light to disable or kill, the latter turned into a weapon of mass destruction by a man who intends to subjugate mankind.

- Afonso Schmidt’s Zanzalá. Brazilian proto-sf novel about a pacific community in the year 2028 which tries to reconcile technology and pastoral life.

- Amelia Reynolds Long’s “The Twin Soul.”

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Miracle of the Lily.” After a war between humans and insect life results in the destruction of nearly all vegetation on the Earth, humans continue to thrive using manufactured food. “The Miracle of the Lily” refers to the possibility that they can reintroduce vegetation to their world centuries after it was first destroyed and at the same time that humans are beginning to establish contact with the native inhabitants of Mars and Venus. Considered her best story — has been reprinted the most and praised by many critics, with Richard Lupoff saying the story would have “won the Hugo Award for best short story, if the award had existed then.” It is the earliest-published story in Lisa Yaszek’s excellent 2018 collection The Future Is Female! 25 Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Fifth Dimension.” Early example of female POV in sf. However, this story is said to be the weakest (and shortest) of Harris’s works. Originally appearing in the December 1928 issue of Amazing Stories, it is a tale of clairvoyance and déjà vu, weakened by the ridiculous dialogue shared by the husband and wife as they ponder how much of their lives are predetermined and what, if anything, can be changed.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Dimension Terror.” (Weird Tales, June 1928). Beetle-men named Nhoj, Luap, Egroeg, and Ognir threaten to take over the psyches of Earth’s impressionable teenaged population.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Polar Doom” (Weird Tales, November 1928) has UFOs destroying cities from their base in the Arctic.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Menace of Mars.” Opens with Harris’s planet-moving concept as described in “A Runaway World,” but the results are very different. As all the planets (and the sun) move closer to each other, most of the Earth becomes inhospitable and the remnants of humanity flee to two colonies at the poles. Hildeth finds himself living in Polaria, at the North Pole, while his fiancé, Vivian Harley takes refuge at Eden, on the opposite end of the world. The title refers to a Martian invasion. Female scientist.

- David H. Keller’s “The Psychophonic Nurse.” Robot nurses raise children.

- David H. Keller’s “The Revolt of the Pedestrians.” May be the most remarkable of Keller’s stories for Gernsback; it is certainly one of the strangest. It is one of the relatively few sf tales before around 1970 to treat the hypertrophy of automobile culture in the twentieth century as dystopian. After centuries, “automobilists” have become almost organically tied to their pollution-emitting cars, have lost the use of their legs, and have made pedestrianism a fatal offense. After the leader of a band of pedestrians turns off all electricity, legless automobilists die helplessly in their millions; the description of the death of twenty million New Yorkers attempting to flee Manhattan is extremely vivid. In the end, two elite pedestrians (see Adam and Eve) meet and prepare to breed, far from any despicable city.

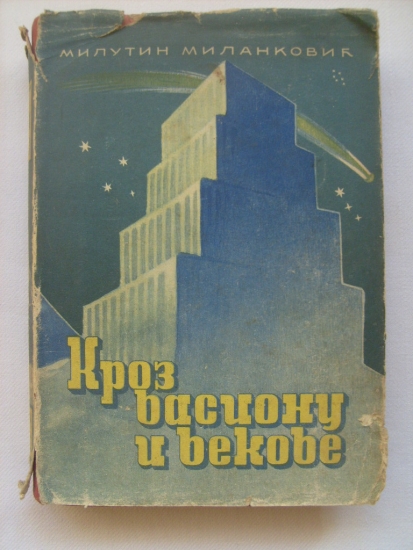

- Milutin Milanković’s Kroz vasionu i vekove (Through Distant Worlds and Times), which combines elements of autobiography, scientific essay and science fiction. Considered a milestone in the history of Yugoslav sf literature. Milanković was a scientist.

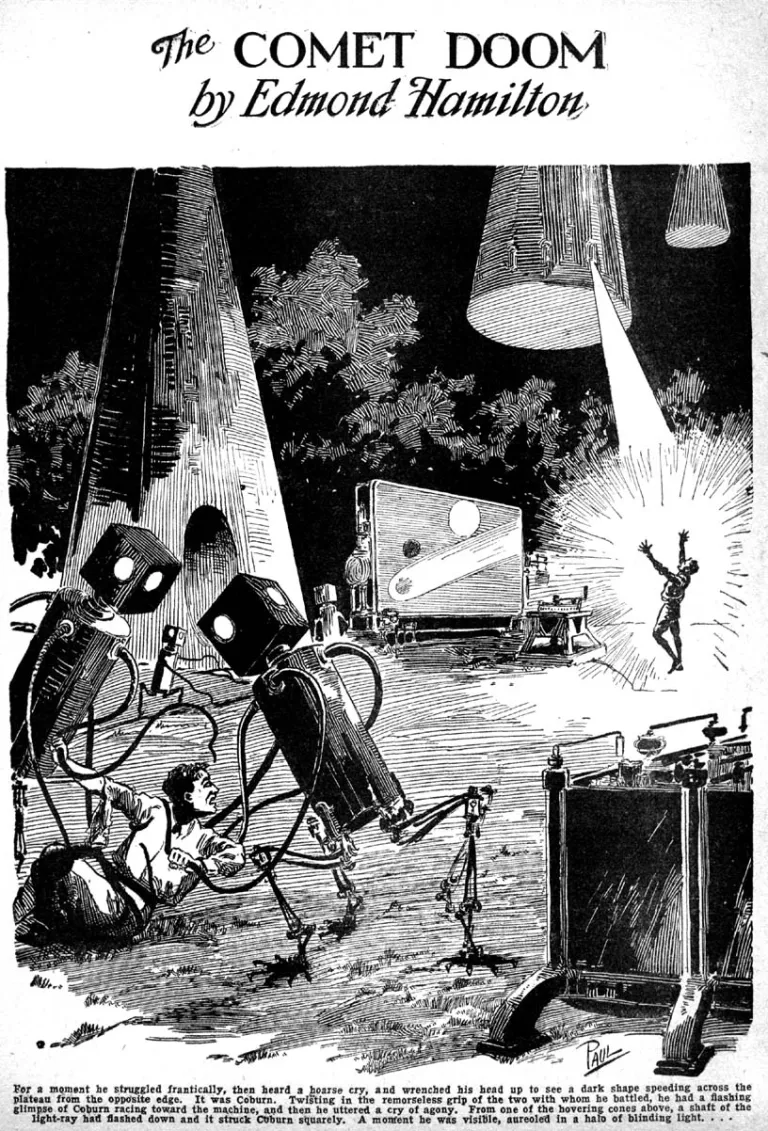

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Comet Doom.” (Amazing Stories, January 1928). A classic tale with killer robots (cyborgs, actually) from a comet, who plan to pull the Earth off-course. One of the heroes becomes one of the cyborgs and fights from the inside. Supposedly a favorite of H. P. Lovecraft’s.

- Edmund Snell’s Kontrol. Evil superman

- Eimar O’Duffy’s The Spacious Adventures of the Man in the Street. A remarkably sharp satire parodying sexual morality, religion, and capitalism.

- Frøis Frøisland’s Fortaellinger fra fronten: Solidt halvlaeder. Norwegian, translated by Nils Flaten as The Man With X-Ray Eyes and Other Stories from the Front in 1930. volume of tales about World War One, several being sf or Horror, including the title tale, about an American soldier whose war wound activates his x-ray vision.

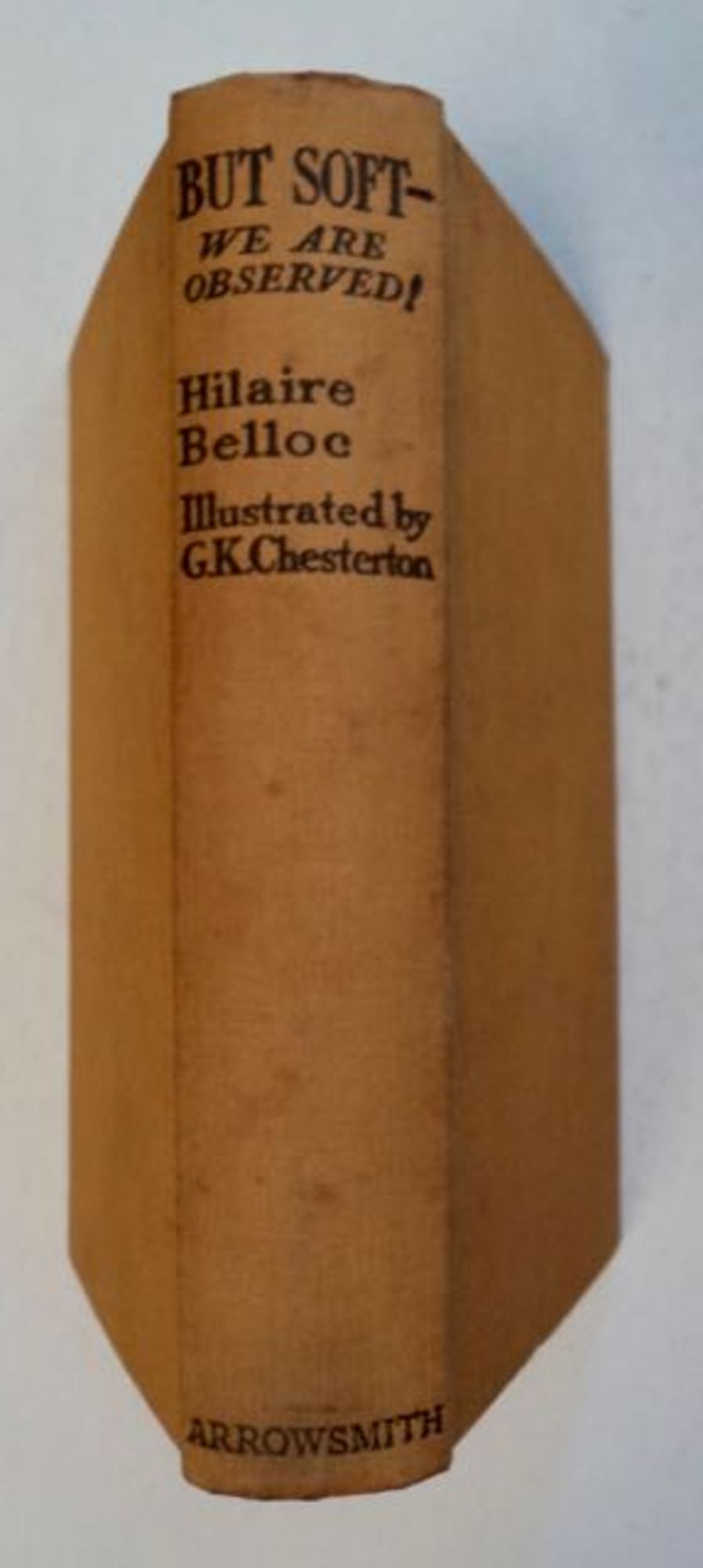

- Hillaire Belloc’s But Soft – We Are Observed! Of the several novels for which his friend and colleague G K Chesterton provided illustrations, But Soft – We Are Observed! is genuine sf, a satirical tale of suspense set in America and Europe in 1979, the main target once again being the parliamentary form of government.

- J. Leslie Mitchell’s Hanno; Or, the Future of Exploration. Part of the To-day and To-morrow series – where Mitchell committed himself to some humorous but basically Wellsian thoughts (he was much influenced by Wells) about exploring both space and the centre of the Earth.

- Jack Williamson’s The Metal Man. Williamson was a discovery of Gernsback’s. After discovering Amazing Stories, and specifically being influenced by its 1927 reprint serialization of A Merritt’s The Moon Pool, Williamson immediately decided to try to write stories for that magazine. His first published fiction, “The Metal Man” in December 1928 for Amazing, was deeply influenced by Merritt’s lush visual style, but like most of his early work conveyed an exhilarating if sometimes unhinged sense of liberation.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Master Ants” (Amazing Stories, May 1928) has a professor and his secretary travel forward in time. Unfortunately, time travel isn’t what it’s cracked up to be, as the machine disintegrates as it ages. The travelers suffer a similar aging, arriving in 2650 as old men. When they arrive they find the world has been taken over by large, intelligent ants. Humans are used as mounts and the females are even milked like cows. The duo escape animal slavery when an airship rescues them and takes them to Science Castle, the last redoubt of humanity in America.

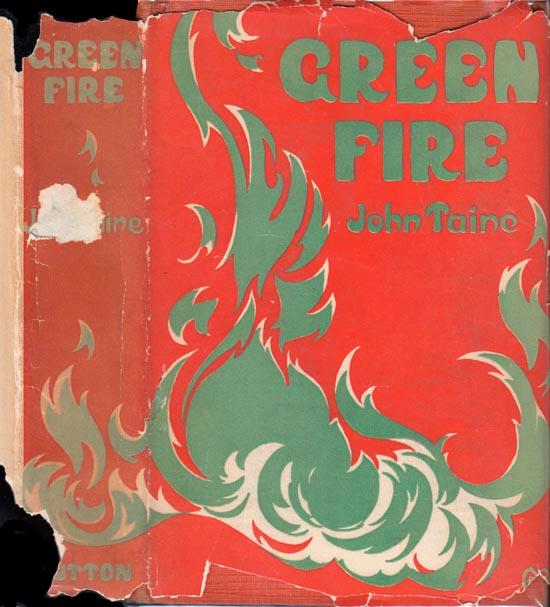

- John Taine’s Green Fire. The novel (set in 1990) concerns two corporations competing to develop the power of atomic energy. Independent Laboratories is working for the advancement of mankind, and Consolidated Power is working for personal gain. A mad scientist attempts to control atomic energy, but almost blows up the universe.

- M.P. Shiel’s “The Future Day” (12-15 March 1928 London Daily Herald as “In 2073 AD”). bout life and love in a Pax Aeronautica world.

- Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger (1913–1966), later famous as a sf writer under the pseudonym Cordwainer Smith, began to publish sf with “War No. 81-Q” (as by either Karolman Junghar or Anthony Bearden) for The Adjutant — the yearbook of the Washington, District of Columbia, Cadet Corps – in 1928. He was fifteen. The tale, plus other unpublished early work, bore some relationship to the Instrumentality of Mankind Universe or Future History into which almost all his mature work fitted. The war concerns a conflict between America and Tibet for the Radiant Heat Monopoly, and it lasts for a mere two hours.

- Rachel Marshall and Maverick Terrell’s “The Mystery in Acatlan.” Parodies convention of “woman as animal.” Is it sf?

- Stanton A Coblentz’s The Sunken World. Coblentz was a discovery of Gernsback’s. A utopia set in a glass-domed Atlantis, in which satirical points are made against both the egalitarian Atlanteans and contemporary America, though the obtuse narrator (of the sort found in most utopias) tends to blur some of these issues.

- Wyndham Lewis’s The Human Age sequence. Lewis was the instigator of Vorticism in 1914. Of particular sf interest is The Human Age sequence, comprising The Childermass: Section 1 (1928; rev vt The Human Age: Book One: Childermass 1956) and Book Two: Monstre Gai; Book Three: Malign Fiesta (coll 1955; vt in 2vols as Monstre Gai 1965 and Malign Fiesta 1966). The arduousness of The Childermass: Section 1, a major twentieth-century Modernist novel, may have kept some readers from its much more clear-cut sequels. SFE claims that this is the closest Modernist literature gets to sf. A fourth volume, The Trial of Man, in which the two protagonists were to be transported to Heaven, remained unwritten. The Human Age depicts the afterlife existence of various characters who must come to understand their condition in an apocalyptic landscape riven by Time Distortions. Pullman and Sattersthwaite, the two freshly deceased protagonists of The Childermass: Section 1, observe and join in the jousting, linguistic and intellectual, that surrounds the Bailiff, a sort of doorkeeper (and exemplar of the bellowing hollowness of modern man) who decides the eligibility of applicants to the Magnetic City (which should be Heaven), but who, in Monstre Gai, leads them into what turns out to be the Third City, a dystopia based on post-World War Two UK. Finding life impossible there, they all make an extraterrestrial journey through “monstrous starlight” to Matapolis in Malign Fiesta, in a parody of the Fantastic Voyage. But Matapolis is Hell, where Sammael rules; as Pullman, realizes: “‘I, Pullman, am acting in a valueless vacuum called Sammael.’ He looked at his apartment. It was a momentary resting place in a vacuum”.

- J. Schlossel’s “The Second Swarm.” Moskowitz notes that it’s a space opera — invasion and counter-invasion. Schlossel was a pioneer contributor of space opera to the pulp magazines, ahead of Edmond Hamilton and E E Smith. He published just six stories. Galactic expansion reappears in this, his second story (Spring 1928 Amazing Stories Quarterly), which describes as background Earth’s attempts at colonizing worlds around distant stars and the resultant conflict with intelligent life in the system around Sirius. See 1925 for his “Invaders from Outside.”

ALSO: Amelia Earhart becomes first woman to fly across the Atlantic. Boas’s Anthropology and Modern Life confutes Fascist theory of “master race.” Geiger develops the “Geiger counter”; teleprinters and teletype writers come into use. Byrd’s first expedition to the Antarctic; Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, written in 1931, would be closely based on Byrd’s account. Carnap’s The Logical Structure of the World (Neo-Positivism). Beginning of first Five-Year Plan in USSR. Hoover elected US president. D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover, Dorothy L. Sayers’s Lord Peter Views the Body, Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. The first Mickey Mouse films; these rely on tropes from the tradition of blackface minstrelsy. Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. High-schoolers Jack Parsons and Edward Forman — adopting the motto per aspera ad astra — begin engaging in homemade gunpowder-based rocket experiments; Parsons had also begun to investigate occultism.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s The Will of the Universe: The Unknown Intelligence. In which the Russian and Soviet rocket scientist who pioneered astronautic theory propounds a philosophy of panpsychism. He believes humans will eventually colonize the Milky Way. Tsiolkovsky did not believe in traditional religious cosmology, but instead (to the chagrin of the Soviet authorities) he believed in a cosmic being that governed humans as “marionettes, mechanical puppets, machines, movie characters,” thereby adhering to a mechanical view of the universe — which he believed would be controlled in the future through the power of human science and industry.

Also this year: It was probably Tsiolkovsky who first went into any detail about the necessity for using “generation starships” in the colonization of other worlds; he presented the idea in “The Future of Earth and Mankind”, which was published in a Russian anthology of scientific essays in 1928.

During the 1920s and 30s, Arthur Eddington gave numerous lectures, interviews, and radio broadcasts on relativity, in addition to his textbook The Mathematical Theory of Relativity, and later, quantum mechanics. Many of these were gathered into books. Eddington’s 1928 book The Nature of the Physical World argues for a deeply rooted philosophical harmony between scientific investigation and religious mysticism, and insists that the positivist nature of relativity and quantum physics provides new room for personal religious experience and free will. “It is necessary to keep reminding ourselves that all knowledge of our environment from which the world of physics is constructed, has entered in the form of messages transmitted along the nerves to the seat of consciousness.”

H.P. Lovecraft’s idea of using higher dimensions of non-Euclidean space as short cuts through normal space can be traced to A.S. Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World which Lovecraft alludes to having read.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin