RADIUM AGE: 1905

By:

May 22, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The pulp magazine space is getting more competitive, now. Munsey launches a second pulp, All-Story — one that places emphasis on complete stories in each issue; it would publish some of the most innovative and memorable fiction the pulps ever produced. Street & Smith, Munsey’s main rival, founds Smith’s Magazine — which will eventually hire Charles Fort as a contributor; and The Monthly Story Magazine begins publication (as of 1907, it will become better known as Blue Book). The Blue Book was among the top three American pulp magazines of the early twentieth century, variously referred to as both “King of the Pulps” and, most recently, “The Slick in Pulp Clothing.” It had a lengthy 70-year run under various titles from 1905 to 1975.

Street & Smith’s The Popular Magazine landed the US serial rights to H. Rider Haggard’s Ayesha in 1905, a sequel to his popular novel She. (Haggard’s Lost World genre influenced several key pulp writers, including Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, Talbot Mundy and Abraham Merritt.)

Hugo Gernsback’s essay “A New Interrupter” appears in Scientific American on July 29, 1905. The twenty-year-old’s first piece published after immigrating to the United States

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1905.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1905, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: RAY-PROOF (from H. R. Haggard’s Ayesha — just in case you don’t think of that novel as proto-sf) | TELEVIEW.

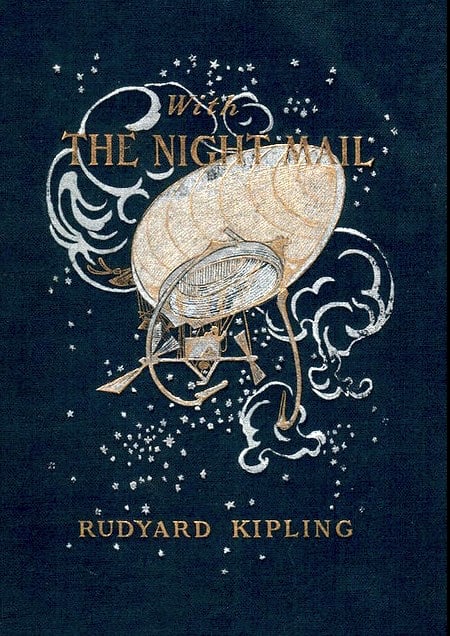

- Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (1905). Kipling’s novella follows the exploits of an intercontinental mail dirigible battling the perfect storm. Between London and Quebec we learn that a planet-wide Aerial Board of Control (A.B.C.) now enforces a technocratic system of command and control not only in the skies but in world affairs. It’s an impressively nuanced portrait of a future in which dirigibles — not airplanes — have triumphed. Kipling goes so far as to include excerpts from the Aerial Board of Control Bulletin, complete with letters to the editor, book reviews, and advertisements. “An amazing tour-de-force of inspired genius,” according to Bruce Sterling. “Kipling, in 1905, is doing things that science fiction as a genre wouldn’t achieve until Robert Heinlein arrived in the late 1940s.” Fun fact: Kipling’s 1912 story “As Easy As A.B.C.” recounts what happens when agitators demand the return of democracy. Both titles were reissued by HiLoBooks, with a new introduction by Matthew De Abaitua and a new afterword by Bruce Sterling.

- Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s Sultana’s Dream (1905). Originally published in English in The Indian Ladies Magazine of Madras, Hossain’s short story depicts a peaceful, crime-free utopia in which women run everything and men are secluded — i.e., in a purdah-like system. What’s more, the women use advanced technology that makes possible laborless farming and flying cars; they have solved the problem of solar energy, and control the weather. Most impressively, perhaps: The workday is two hours long, since men used to waste six hours of each day in smoking! Fun fact: One of the first examples of feminist science fiction. The author was a Muslim feminist, writer, and social reformer who lived in British India. Included in Voices from the Radium Age (MIT Press), a 2022 story collection edited by yours truly. See my essay on Begum Rokeya.

- Edwin Lester Arnold’s Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation (1905). In this satirical, nightmarish, episodic update of Gulliver’s Travels, Lieut. Gullivar Jones, an arrogant US Naval officer, travels to Mars (a jungle planet, not the desert planet of other Mars sci-fi) via magic carpet. There, he gains super strength and telepathic powers, and proceeds to stumble into and out of trouble. There is a war brewing between the beautiful, innocent, sophisticated Hither Folk and the barbaric, industrious Thither Folk; Gullivar fails to prevent the war, and flees back to Earth. He also attempts to claim a vast tract of Mars for himself, travels down a river of death, fails to outwit or defeat his enemies, and doesn’t win the hand of beautiful Princess Heru. Fun fact: Arnold was best known in his own time for the 1890 fantasy novel The Wonderful Adventures of Phra the Phoenician. Note that Edgar Rice Burroughs’s first John Carter novel was likely inspired by Lieut. Gullivar Jones; and the flying cities of Flash Gordon and other, later sci-fi, find their precursor here, in the city of Laputa. An example of first-time-as-comedy — Burroughs would find success doing a non-comedic version of the story.

- George Allan England’s “The Time-Reflector” — in The Monthly Story Magazine. About the invention of a time viewer device. England’s first work of sf interest. He was a prolific author of more than 330 stories. His work appeared predominantly in Munsey’s magazines, where he was one of the more popular writers of the pre-1926 period, ranking as the closest rival in sf to Edgar Rice Burroughs.

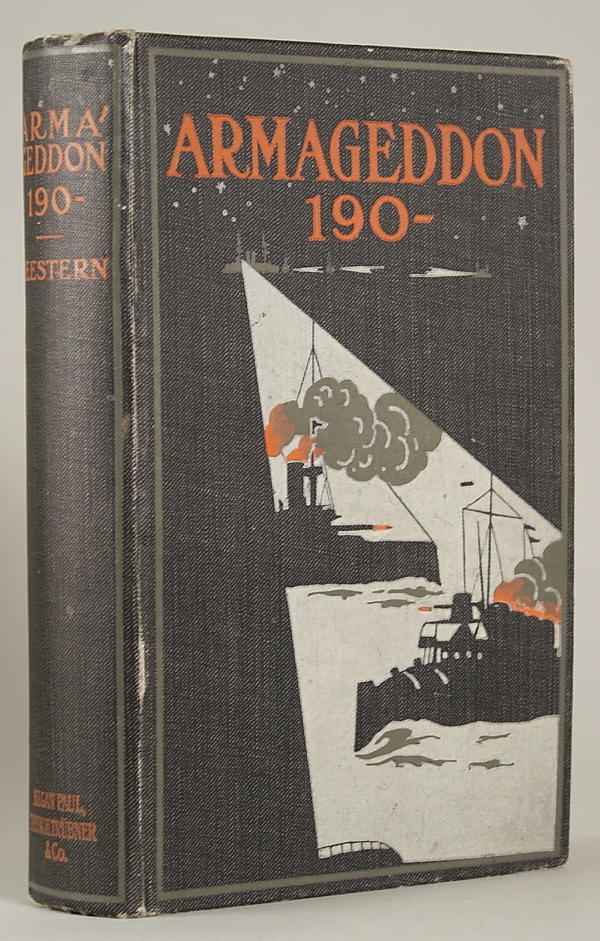

- Ferdinand H. Grautoff’s Armageddon 190_. Shown here is a 1907 translation of 1906: Der Zusammenbruch der Alten Welt (1905, as by Seestern). Account of an imaginary world war set in the near future that exhausts the European nations and shifts the balance of power to the United States and Russia. “The English introduction of the revolutionary dreadnought battleships, and the Moroccan crisis of 1905, stimulated the writing of a number of German war visions. The most successful of these was Grautoff’s book. By 1907, 125,000 copies had been published. This best seller would serve as an archetype for the genre well into the 1930s.

- Gustave Le Rouge’s story “L’Espionne du Grand Lama” (The Grand Lama’s Spy) is a Lost World tale. An early story by a significant figure in early twentieth-century French sf, much admired by the Modernist/Surrealist author Blaise Cendrars. See 1908 for info on Le Rouge’s Vampires of Mars sequence.

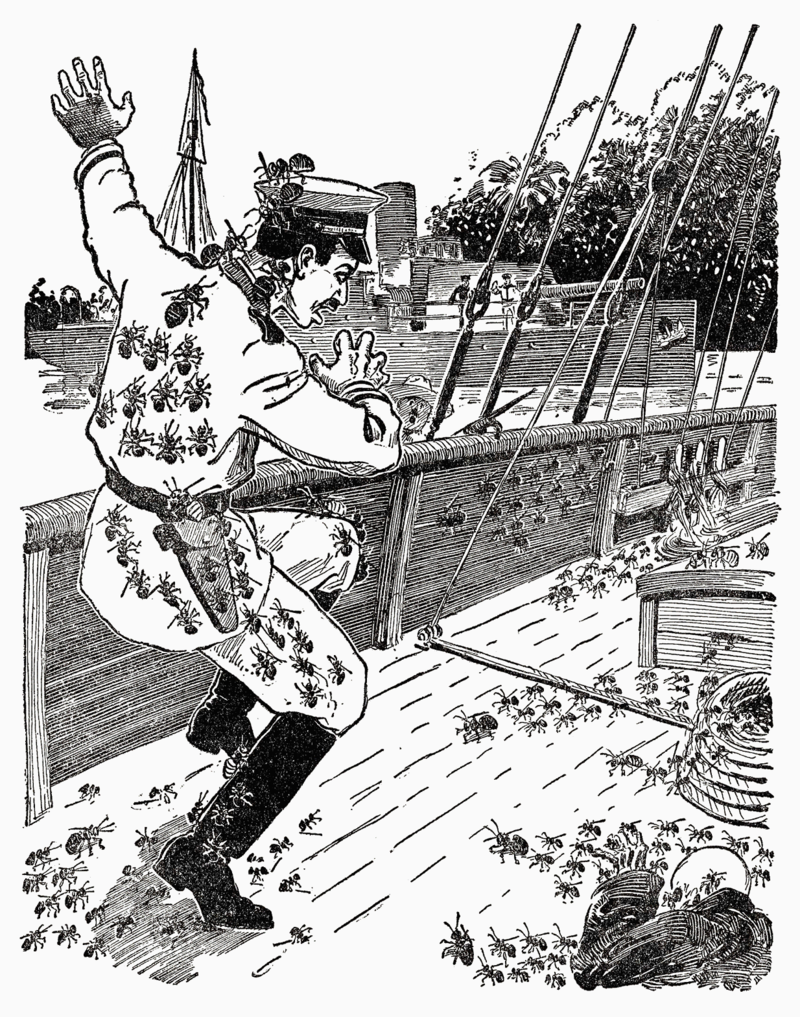

- H.G. Wells’ story “The Empire of the Ants” — about the tenuousness of the dominion that Homo sapiens enjoys on Earth. A species of large black ant has evolved advanced intelligence, makes tools, and organizes aggression.

- Lucas Cleeve (Adelina Georgina Isabella Kingscote)’s A woman’s aye and nay. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Maurice Renard’s “Les Vacances de Monsieur Dupont” involves time travel into a prehistoric territory inhabited by dinosaurs. Collected in Fantômes et fantoches (Phantoms and Puppets, as by Vincent Saint-Vincent.). The first story by an author generally regarded in France as the most important native sf writer in the first decades of the twentieth century, heavily influenced by the work of J-H Rosny aîné.

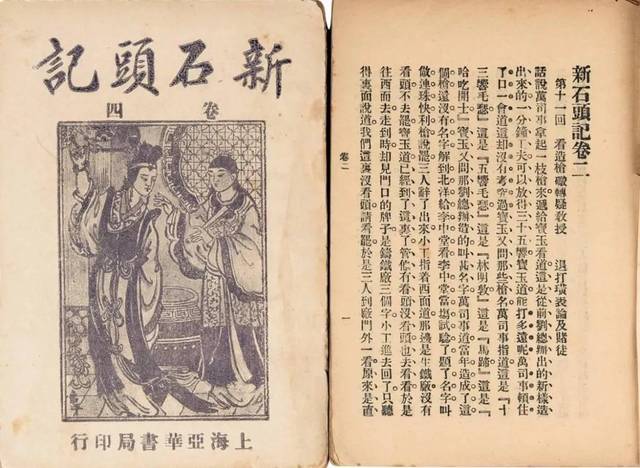

- Wu Jianren [Wujian Ren]’s New Story of the Stone (Xin shitou ji), one of the most complete visions of a Chinese utopia, according to Isaacson. And one of the most widely read texts of the late Qing; in fact, it is an encyclopedia of late Qing SF tropes (e.g., the reform of the people’s diet, automated sewing clothes, weapons of electrification, farming mechanization, and artificial climate control). Isaacson suggests inspiration from Bellamy’s Looking Backward. The first half of this book reflects the sordid reality of Chinese society at the beginning of the 20th century, while the second half focuses on the blueprint of the author’s ideal “civilization state.” Originally published in Shanghai Nanfang Daily from August 21 to November 29, 1905.

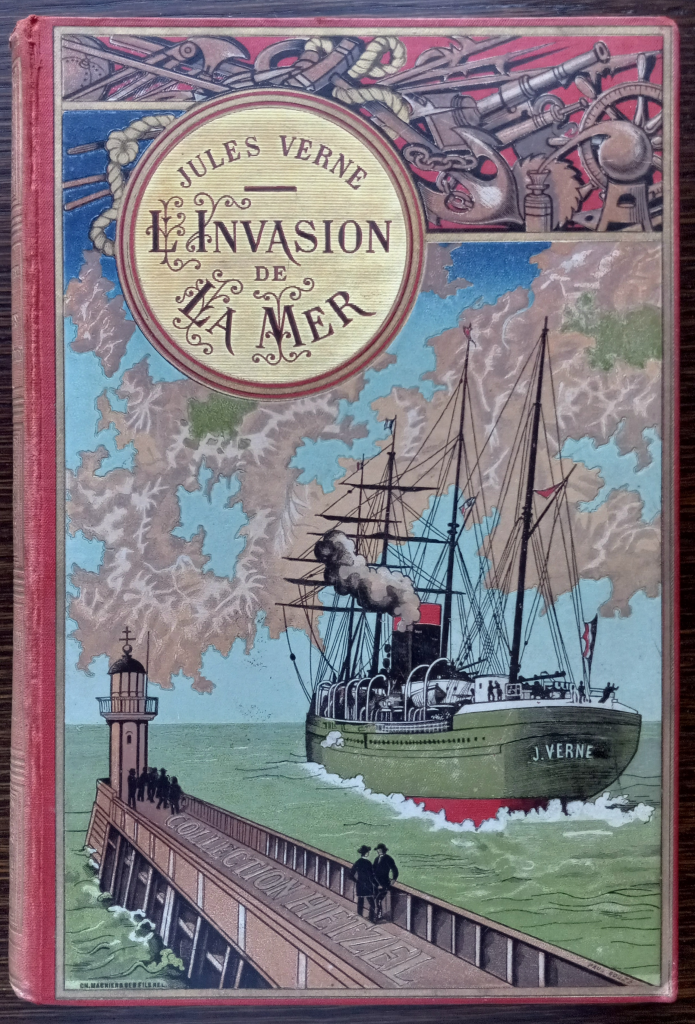

- Jules Verne’s Invasion of the Sea (French: L’Invasion de la mer) was the last to be published in the author’s lifetime. It describes the exploits of Berber nomads and European travelers in Saharan Africa, in the 1930s. The European characters arrive to study the feasibility of flooding a low-lying region of the Sahara desert to create an inland sea and open up the interior of Northern Africa to trade. In the end, however, the protagonists’ pride in humanity’s potential to control and reshape the world is humbled by a cataclysmic earthquake which results in the natural formation of just such a sea.

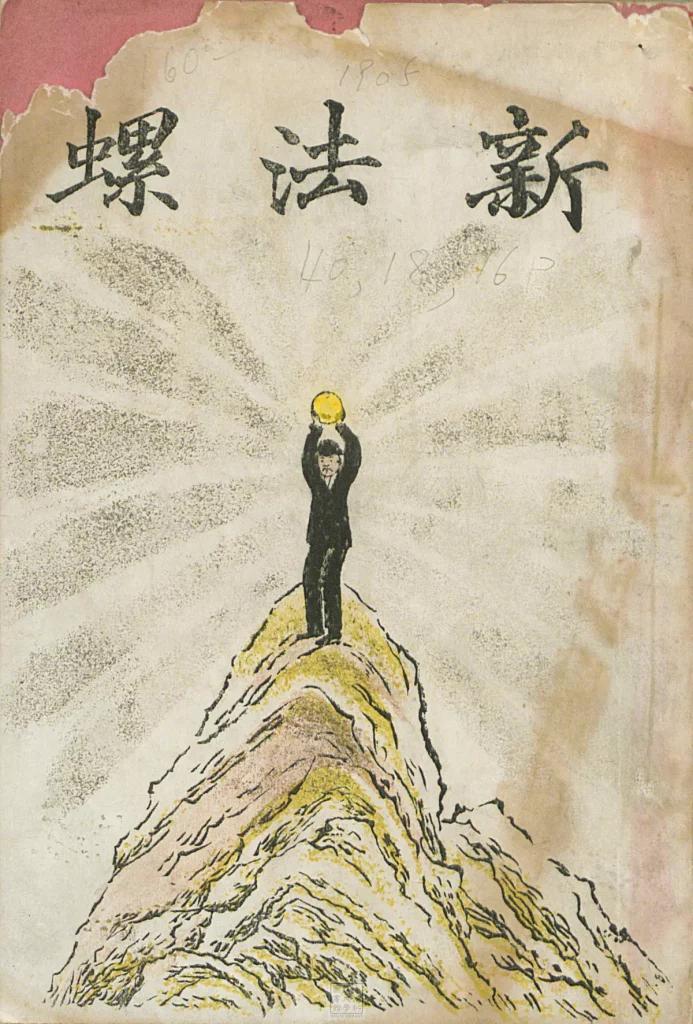

- Xu Nianci’s Xin Falu Xiansheng Tan (New Tales of Mr Absurdity / New Tales of Mr Braggadocio / A Tale of New Mr. Braggadocio). China’s earliest purely literary periodical, Forest of Fiction (小說林), founded by Xu Nianci, not only published translated science fiction, but also original science fiction such as A Tale of New Mr. Braggadocio (新法螺先生譚). A curious combination of foreign sources and literary traditions, classical Chinese traditions of the zhiguai (tales of the strange and supernatural) and chuanqi (fantastic tales and romances), and modern scientific and pseudo-scientific theories, written in a deliberately archaic style. It is presented as a fantastic voyage in which the title character’s body and soul experience separate adventures. Concerned with issues of nation-building that draw from technological progress and scientific rationalism on the one hand, and theories of spiritual transcendence, hypnosis, and psychic communication on the other. New Mr. Braggadocio’s invention of brain electricity emits light that replaces manmade light, sound that surpasses the need for telegraph and telephone companies, heat that makes redundant the need for heating, and telepathic conduits that compete with traditional transportation networks. Ultimately, the wondrous powers of brain electricity, instead of bettering society, end up causing massive unemployment worldwide and the story concludes with the narrator having to go into hiding. In the preface, Xu explains how he was inspired to write the story after reading Bao Tianxiao’s Chinese translation of the Japanese Meiji writer Iwaya Sazanami’s work, Hora Sensei [Mr. Absurdity, 1895], which was in turn translated and adapted from the eighteenth-century German burlesque The Wonderful Travels of Baron Münchhausen (1786) by Gottfried August Bürger.

- Martha Foote Crow’s The World Above: A Duologue. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- G.K. Chesterton’s The Ball and the Cross (1905-1906; expanded version, as book, 1909), a Professor Lucifer invents a fantastic flying machine and subtly poisons a near-future England. (“All the tools of Professor Lucifer were the ancient human tools gone mad, grown into unrecognizable shapes, forgetful of their origin, forgetful of their names. That thing which looked like an enormous key with three wheels was really a patent and very deadly revolver. That object which seemed to be created by the entanglement of two corkscrews was really the key. The thing which might have been mistaken for a tricycle turned upside-down was the inexpressibly important instrument to which the corkscrew was the key.”) Concerns the dueling, figurative and somewhat more literal, of a Jacobite Catholic named Evan Maclan and an atheist Socialist named James Turnbull. The real antagonist is the world outside, which desperately tries to prevent from happening a duel over “mere religion” (a subject both duelists judge of utmost importance). An allegory in which Faith and Reason join forces against Satan.

- Lena Jane Frye’s Other Worlds: a Story Concerning the Wealth Earned by American Citizens and Showing how it can be Secured to Them instead of to the Trusts. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Margaret Montague Prescott’s “The Great Sleep Tanks” in The All-Story Magazine (January 1905). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Allen Upward’s The International Spy: Being a Secret History of the Russo-Japanese War. Is it sf?

- Howard R. Garis’s “Professor Jonkin’s Cannibal Plant” — first in a series of silly invention stories by the creator of Uncle Wiggily.

- F. E. Mills Young (Florence Ethel Mills)’s The War of the Sexes. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- In his unfinished novel, Three Thousand Years Among the Microbes (w. 1905), Mark Twain uses a fictional microbial landscape to imaginatively test solutions to the ethical entanglements brought about by the realization that we share our world with an untold number of microscopic organisms. The narrator of the satire, having been reduced to microscopic size by a wizard, explores the world-body of a diseased tramp, Blitzowski (one of whose inhabitants is called Lemuel Gulliver, the influence of Jonathan Swift being apparent throughout); it is implied that the universe we inhabit is actually God’s diseased body.

- Bessie Story Rogers’s As It May Be: A Story of the Future. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

ALSO: Einstein formulates Special Theory of Relativity and establishes law of mass-energy equivalence; note however that Einstein’s theory will not reach the general public until after WWI. Poincaré proposes gravitational waves (ondes gravifiques) emanating from a body and propagating at the speed of light as being required by the Lorentz transformations. William Bateson, English biologist who was the chief popularizer of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscovery in 1900, coins the term “genetics” to describe the study of heredity. Karl Pearson proposes the random walk (a random process that describes a path that consists of a succession of random steps on some mathematical space) in a letter to Nature. The first neon light signs. The first workers’ soviet formed in St. Petersburg; the revolutionary movement reaches its climax in October with the declaration of a general strike. Sinn Fein party founded in Dublin. Sun Yat-sen founds a union of secret societies to expel the Manchus from China. William Haywood and others found the IWW. Wharton’s House of Mirth, Marinetti’s “Futurist Manifesto,” Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel. Richard Strauss puts Wilde’s Salome to music and launches it as an opera. Modernism in art takes off with an exhibition by the Fauves (wild beasts) in Paris. In general, the fin de siècle mood of decadence and despair begins to give way (around 1905) to an era of socialism, internationalism, a buoyant futurism.

See 1904 for William James and constructive postmodernism. In 1905, Peirce makes a clear break with his own earlier modernism.

Poincaré’s “Space and Geometry” helped change the cultural discourse.

Expressionism emerged in various cities across Germany as a response to a widespread anxiety about humanity’s increasingly discordant relationship with the world and accompanying lost feelings of authenticity and spirituality. In part a reaction against Impressionism and academic art, Expressionism was inspired most heavily by the Symbolist currents in late-19th-century art. Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and James Ensor proved particularly influential to the Expressionists, encouraging the distortion of form and the deployment of strong colors to convey a variety of anxieties and yearnings.

Art was now meant to come forth from within the artist, rather than from a depiction of the external visual world.

The classic phase of the Expressionist movement lasted from approximately 1905 to 1920 and spread throughout Europe

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin