RADIUM AGE: 1904

By:

May 15, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The year 1904, in my periodization scheme, marks the beginning of the cultural decade known as the “Nineteen-Aughts.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1904 (and 1903) as cusp years during which the Eighteen-Nineties end and the Nineteen-Aughts begin.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that the Radium Age of proto-sf begins in 1904 — this is in part because Wells’s 1904 novel A Modern Utopia would spark a cottage industry in dystopian proto-sf satirizing aspects of this novel in particular. See 1909, for example: E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops. Also Max Beerbohm’s “General Cessation Day” (1912), Victor Rousseau’s The Messiah of the Cylinder (1917), etc.

Street & Smith’s boys’ periodical, The Popular Magazine, was converted to an all-adventure pulp in 1904.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1904.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1904, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: TIME-TRAVELLING (from a magazine feature on H.G. Wells).

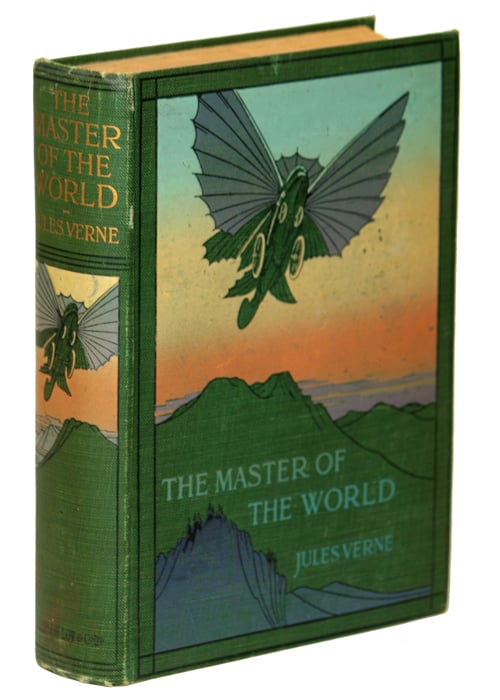

- Jules Verne’s The Master of the World (1904). In this sequel to Verne’s 1886 adventure Robur the Conqueror, FBI(-ish) Chief Inspector Strock arrives in North Carolina to investigate what appears to be an imminent volcanic eruption. Meanwhile, a supercar is spotting traveling at 120 miles per hour; and a speedboat/submarine is glimpsed in the waters off New England. Aha! The brilliant inventor Robur is back, and this time he has invented a ten-meter long multi-purpose vehicle, The Terror. Determined to have it for military purposes, the feds first attempt to buy the machine, then attack Robur. With a captive Strock aboard, Robur escapes in The Terror over Niagara Falls, then challenges God by heading into a Caribbean thunderstorm… at which point his amazing craft is shattered by lightning. Here we see one of the genre’s pioneers, at the end of his career (and life), questioning man’s ability to use science and technology to benefit humankind.

- Huangjiang Diaosuo’s “Yueqiu zhi Mindi Xiaoshuo” (“A Tale of Moon Colonists,” serialized 1904–1905) is picaresque Edisonade in which exiles from modern China tour the world in a hot-air balloon, trying new inventions, encountering strange races and customs (representing aspects of Chinese society that need remedying), and eventually reaching the Moon. China’s first native work labeled as science fiction. (Nathaniel Isaacson suggests the term “science fiction” (kexue xiaoshuo) as a literary genre category was used in China before it began to appear in the English language press.)

- Marie Blaze de Bury’s The Storm of London: A Social Rhapsody (as by F. Dickberry). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

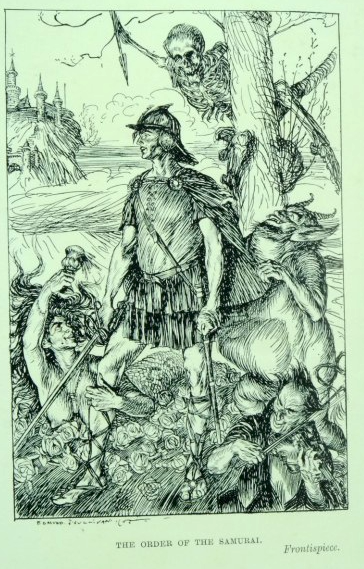

- H.G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia (serialized in the Fortnightly Review, October 1904-April 1905; as a book, 1905). The novel is best known for its notion that a voluntary order of nobility known as the Samurai could effectively rule a “kinetic and not static” world state so as to solve “the problem of combining progress with political stability”. Alternate History of one kind or another had already been written decades earlier – but Wells seems to be the first to posit that when you make the transit to the Utopian timeline in the Alps, you find yourself in the very same spot in the other world’s Alps, and when you travel in the Utopian world to an Utopian London and then cross back to our world, you find yourself on the same spot in our mundane London. This one-to-one correspondence was taken up by countless others, and is now taken for granted by any Alternate History fan – but it should be added to the great list of standard Science Fiction plot devices for which we are in debt to Wells’ genius. A Modern Utopia is also notable for Chapter 10 (“Race in Utopia”), an enlightened discussion of race. Contemporary racialist discourse is condemned as crude, ignorant, and extravagant. E.M. Forster would satirize what he regarded as the book’s unhealthy conformism in his 1909 proto-sf story “The Machine Stops.” Indeed, this is probably one of the most satirized sf books of all time.

- I. Crane Clark’s “Where is Robert Palmer” — in The Black Cat. Is it sf?

- H.G. Wells’s “The Country of the Blind.” Collected in Science Fiction: The Science Fiction Research Association Anthology (1988, ed. Martin H. Greenberg, Patricia S. Warrick, Charles G. Waugh).

- John Davidson’s The Testament of a Prime Minister — with an inferno-like vision of East London. Fun fact: Scottish schoolteacher, poet, playwright and author, his intensely urban poetry, much of which focuses on science and technology from an almost mystical point of view, had a shaping influence now forgotten. He wrote Nietzschean scientific romances, while in the Testaments series, a cosmological sublime soars beyond the Nietzschean.

- Robert W. Chambers’ In Search of the Unknown (linked stories). A man obsessed with exploring the farthest reaches of the natural world is driven to digging out the hidden wonders. His travels take him to distant lands where strange creatures lurk in the shadows and swamps, fearsome birds, invisible predators, and a monstrous proto-Black Lagoonish creature known only as “The Harbor Master”. SFE says: “US author, author of over 70 novels in various genres, mostly historical and romantic works, increasingly popular but increasingly bad.” This is part of his Lost Species sequence – includes Police!!! (collection of linked stories, 1915). Features the adventures of a philandering zoologist in his search for unknown beasts; he finds them – sometimes in Lost Worlds where monsters and ape-men roam. Fun facts: The pioneering “weird fiction” author Chambers was best known for his book of Art Nouveau short stories The King in Yellow (1895). His contemporaries tended to agree that he had good ideas and innate talent but rarely put in the effort to actually write well. Lovecraft on Chambers: “I think The Yellow Sign is the most fascinating product of Chambers’s pen, & altogether one of the greatest weird tales ever written. The brooding, gathering atmosphere is actually tremendous. The Harbour Master gave me quite a wallop in 1926 when I read it…” (to J. Vernon Shea, 28 January 1933).

- George Griffith’s The Stolen Submarine. Bleiler says “lacks even the unstructured imagination of the earlier Griffith novels.”

- Octavia Zollicoffer Bond’s “A Rule That Worked Both Ways” — in The Black Cat. An sf-ish ghost story in which radium is used to make spirits visible.

- Valery Bryusov’s Symbolist play Zemlya (Earth), about a future apocalyptic Earth.

- William Wallace Cook’s Adrift in the Unknown, or Adventures in a Queer Realm (1904–1905, in The Argosy, 1905 as a book). A satire in which a burglar goes along for a ride with a reformist scientist in his spaceship to Mercury, where he teaches lessons in social justice to the kidnapped capitalists he has brought with him.

- Edward Johnson’s Light Ahead for the Negro. It images a post-racist American culture, where African Americans are given land and equal rights. Our point-of-view character, who’s later called Gilbert Twitchell, boards a friend’s airship in a voyage to Mexico. The motor explodes in the air and he loses consciousness in the effort to save himself and his friend. He awakes alone in a room in Phoenix, Georgia – in 2006 – being cared for by the occupants of the house on whose lawn he had landed. A woman finds papers of his dating back to 1906 in his pocket. Edward Johnson was a historian, attorney, politician and educator.

- G.K. Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904). In an alternative-history version of England (it’s set in 1984), monarchs are selected at random instead of inheriting the title. When Auberon Quin, a man who aspires to live life like a medieval adventure, becomes king, he mandates that each of London’s neighborhoods become an independent state, complete with unique local costumes. Everyone goes along with the conceit until young Adam Wayne, a born military tactician, takes the game too seriously… and becomes the Napoleon of Notting Hill. War rages throughout the city — fought with sword and halberd. Fun fact: Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins is known to have admired The Napoleon of Notting Hill. Here are my notes for a movie adaptation. To be published in MIT Press’s Radium Age series, with an introduction by Madeline Ashby.

- Fenton Ash’s The Radium Seekers, or The Wonderful Black Nugget (1904 Boy’s Realm; 1905 as a book)

- Rosetta Luce Gilchrist’s Tibby: A Novel Dealing with Psychic Forces and Telepathy. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Elise Touchemolin/Jen Delaire’s Around A Distant Star — a religious sf novel in which a spaceship and supertelescope allows a scientist to see back in time to Jesus’s crucifixion. The narrator then returns to Earth, leaving his friend behind to teach Christianity to the monkey-like natives of another planet.Ashley claims it is “remarkable,” and Moskowitz calls it a precursor to the space opera of E.E. “Doc” Smith. But it’s reportedly not very exciting. Note that Touchemolin would serve as president of the Brighton (UK) Lodge of Theosophists c. 1909–1919.

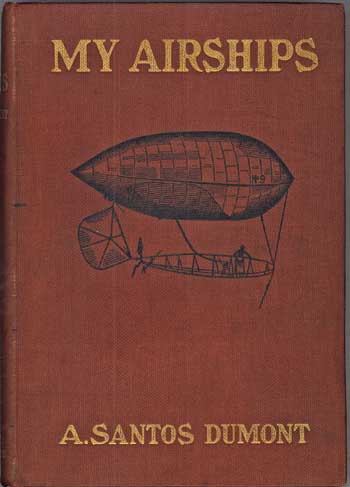

- Emilio Salgari’s I figli dell’aria (Children of the Air). A Russian and a Cossack voyage across China to the mountains of the Himalayas via an airship manned by a mysterious captain.

- H.G. Wells’s The Food of the Gods (1904). The First Men in the Moon (1901) is Wells’s last terrific sf novel; The Food of the Gods is his first un-terrific one. However! Un-terrific Wells is still pretty damn good. A chemical intended to make chickens grow larger accidentally causes plants, wasps, earwigs, and rats to grow as well… and it spawns a race of human giants, too, who must struggle to survive. Fun fact: The 1977 Marvel Classics Comics edition of the story is great.

- L.T. Meade (pseudonym of Elizabeth Thomasina Meade Smith)’s Silenced — series of six linked sensational crime stories, four first published in THE STRAND MAGAZINE. The stories are related by patients to a philanthropic doctor who operates Sherwood Towers, a sanatorium in rural England. Three of the stories, “The Man Who Disappeared,” “Spangle-winged” and “The Blue Laboratory,” are weird tales or science fiction.

- Frank L. Pollock’s “The Skyscraper in B Flat” — in The Black Cat — is an example of proto-sf’s fascination with the power of vibrations.

- Francis Stevens’s (Gertrude M. Barrows) “The Curious Experience of Thomas Dunbar” — an early lab-created superman story, by a pioneering female author. An injured man, recuperating at the home of a scientist, absorbs the super-force of a new element called stellarite. Published in The Argosy as by G.M. Barrows.

- Gabriel Tarde’s Underground Man (Fragment d’histoire future; 1905 in English). Tarde was a French sociologist, criminologist and social psychologist. Catastrophe novel set in the future. The sun is cooling and humanity moves underground to survive, creating a new world and a new society. The novel “depicts first a world society on the surface of the earth, then, with the exhaustion of the sun’s energy, a sanitary underground utopia. The author seems to evince satirical doubts about the value of the latter as a model for human conduct.” – Clute and Nicholls (eds), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

- James Barnes’ The Unpardonable War. A war between England and America. After war between Britain and America has been incited because America wishes to free Ireland and to annex Canada, the scientific genius Westland, “the Wizard of Staten Island,” invents a device which explodes the enemy’s gunpowder. America then takes the lead in suppressing war everywhere.

- George W. Bell’s Mr. Oseba’s Last Discovery — A curious book which recounts the experiences of an inhabitant of a Symmes-style inner world when he visits the outer surface of the world. Fictionalized account of New Zealand (Zelania) as eutopia.

- Fred M. White’s “The River of Death” — for more London in Peril stories by White, see 1903. Collected in Beyond the Gaslight: Science in Popular Fiction 1895–1905.

- Violet Guttenberg’s A Modern Exodus. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- H. Rider Haggard’s Ayesha: The Return of She (December 1904-October 1905 Windsor Magazine, as a book in 1905) — a work of anthropological sf (though it’s also been described as gothic fantasy and imperial gothic). A sequel to She: A History of Adventure (1886). Chronologically, it is the final novel of the Ayesha and Allan Quatermain series. Set in Tibet, here Ayesha shows Holly and Leo how she commands mortals, spirits, and demons. She questions Holly at length about the modern world and expounds to him her plan that, once united with Leo, they will rule the world, conquering the existing Empires by flooding the world’s gold supply with her alchemy. (See similar plot — with literal flooding — of Haggard’s When the World Shook.) The Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction website credits Haggard with coining the term “ray-proof” here: “Ayesha began to loose Leo from his ray-proof armour — if so it can be called — and he in turn loosed me.” Fun fact: C.S. Lewis patterned Empress Jadis on She, in the sixth book of the Narnia series, The Magician’s Nephew. This and other Haggard stories have been called a central model for Edgar Rice Burroughs and the Science-Fantasy subgenre — a pattern in which realistic portraits of the contemporary world are combined with backward-looking displacements to give a general effect of deep nostalgia. Haggard was also interested in Spiritualism, whose influence can be detected in these books. Listed in the Science Fiction After 1900 timeline.

- Owen Oliver’s “Out of the Deep” — derivative of War of the Worlds. Huge fish employing “piscine magnetism” develop artificial gills and other tools made of a new metal, and attack humankind. Tongue-in-cheek? Excellent illustrations by Warwick Goble (who’d illustrated Wells’s The War of the World in 1897) for Harmsworth/London Magazine (August 1904).

- The two stories in The Merry Multifleet and the Mounting Multicorps were created by cartoonist Richard Johnson, and then transcribed by Thomas O’Cluny.

- L. J. Beeston’s “A Star Fell” — collected in Science Fiction by the Rivals of H. G. Wells.

- George Griffith’s From Pole to Pole — novelette, variant of From Pole to Pole: An Account of a Journey Through the Axis of the Earth; Collated from the Diaries of the Late Professor Haffkin and His Niece, Mrs. Arthur Princeps — collected in Science Fiction by the Rivals of H. G. Wells, and Beyond the Gaslight: Science in Popular Fiction 1895–1905. Griffith was one of the most influential sf writers of his time — though always overshadowed by Wells. He was instrumental in the transformation of the Future War novel to a more sensational form, capitalizing on contemporary political anxiety; and he helped make up a literary coterie, including William Le Queux, M.P. Shiel, and Louis Tracy, which specialized in the genre.

- Sax Rohmer’s “The Green Spider” — as by Arthur Sarsfield Ward

- Rudyard Kipling’s Traffics and Discoveries — stories and poems, a couple of which have sf interest. The “Wireless” story involves experimental drugs and short-wave radio; “The Army of a Dream” is a sort of proto-Heinlein piece of propaganda suggesting that one ought not to be a citizen unless one becomes a veteran of the military.

- G.F. Bradby’s Joshua Newings, or The Love Bacillus. Of sf interest for its description of love as the side effect of a parasitic disease. The protagonist, a bachelor, is not entirely cured. The SFE says that “the satire is mild.”

ALSO: Rutherford and Soddy postulate general theory of radioactivity. Soddy’s Radioactivity. Curie’s Recherches sur les substances radioactives. Russo-Japanese War breaks out; first trenches used. Poincaré intervenes in the trials of Alfred Dreyfus, attacking the spurious scientific claims regarding evidence brought against Dreyfus. Conrad’s Nostromo, London’s The Sea-Wolf, Barry’s Peter Pan, Baum’s The Marvelous Land of Oz, E. Nesbit’s The Phoenix and the Carpet, James’ The Golden Bowl, Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard. Freud’s The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (an account of the rise of rationality in the west, leading ultimately to the modern moment in which magic, myth, and mysticism have been displaced by a steady dispersal and diffusion of scientific and technical methods of calculation and control exercised over nature and culture — at the cost of neglecting the fundamental values which constitute the end of human action or conduct, and at the cost of subverting individual creativity and autonomy and the values of democracy), Veblen’s The Theory of Business Enterprise.

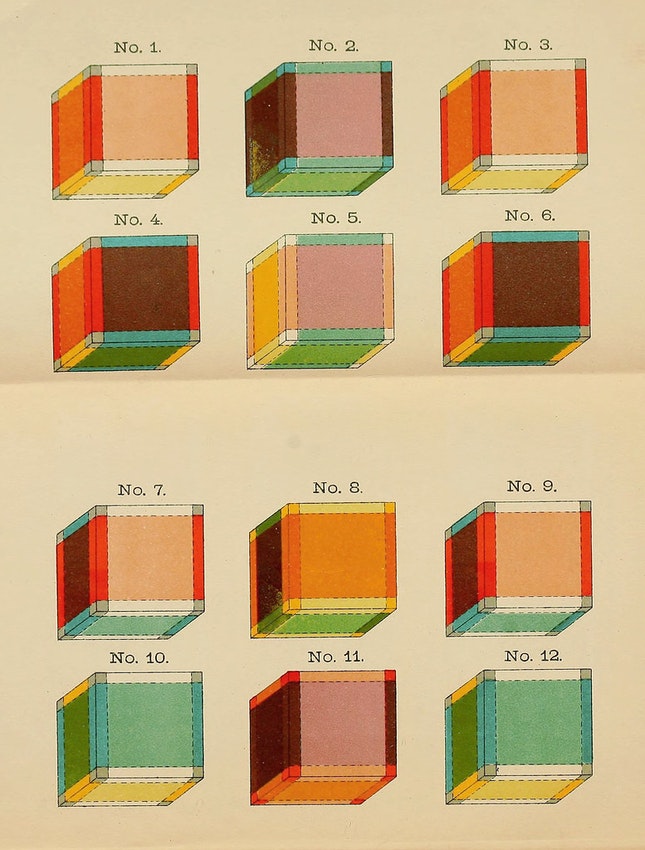

Charles Howard Hinton’s The Fourth Dimension published this year. (See Jon Crabb’s fascinating HILOBROW post on the subject.) Hinton was a British mathematician interested in higher dimensions, particularly the fourth dimension. He is known for coining the word “tesseract” and for his work on methods of visualizing the geometry of higher dimensions; his writings on higher dimensions were a key influence on P. D. Ouspensky’s thinking. Hinton’s wife, Mary Ellen, was daughter of George Boole, the founder of mathematical logic, and Mary Everest Boole, a self-taught mathematician who encouraged children to explore mathematics through playful activities such as curve stitching. Here his practical program of developing in oneself the conscious mental ability to penetrate to the fourth dimensions (which he has been publishing about since the 1880s) reaches its highest degree of elaboration. Hinton also wrote several fourth dimension-related scientific romances (published as pamphlets) from 1884–1886. Fun fact: Hinton is name-checked in Jorge Luis Borges’ 1961 story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.”

As Crabb notes in his post on the topic, Hinton’s book promises that when visualization of higher dimensions is achieved, his cubes can unlock hidden potential. “When the faculty is acquired — or rather when it is brought into consciousness for it exists in everyone in imperfect form — a new horizon opens. The mind acquires a development of power.” Hinton suggested that the soul itself is “a four-dimensional organism, which expresses its higher physical being in the symmetry of the body, and gives the aims and motives of human existence.” Letters submitted to mathematical journals of the time indicate more than one person found the process of visualizing the fourth dimension profoundly disturbing or dangerously addictive.

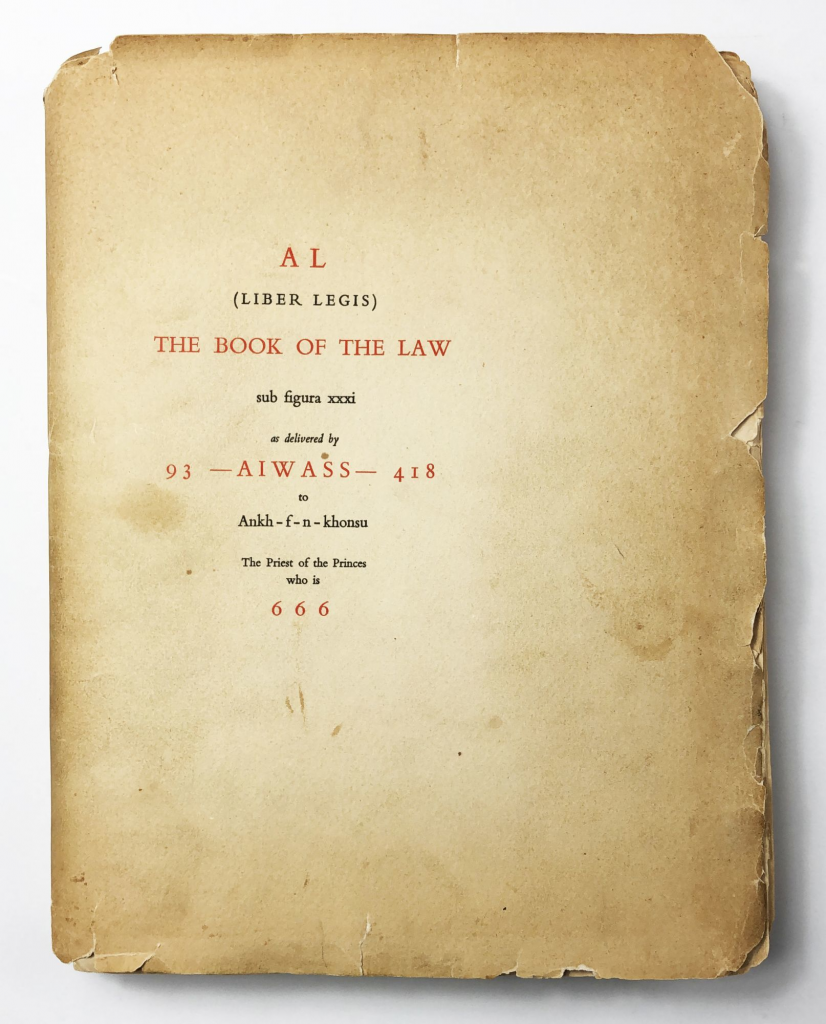

Liber AL vel Legis (The Book of the Law), the central sacred text of Thelema (the religion founded by Aleister Crowley, which tells its followers that “do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law”), dictated to Crowley — by a possibly non-corporeal being calling itself Aiwass — in 1904. Crowley identified himself as the prophet of a new age, the Æon of Horus, based upon this spiritual experience. In my reading, there is a structuralist (or semiotic parole/langue) design to Crowley’s cosmology. The highest deity is the goddess Nuit, the collection of all possibilities, “Infinite Space, and the Infinite Stars thereof,” and the circumference of an infinite circle or sphere; a semiosphere, if you will. The second principal deity is Hadit, conceived as the infinitely small point, complement and consort of Nuit. Hadit symbolizes manifestation, motion, and time, “the flame that burns in every heart of man, and in the core of every star.” One must discern and obey one’s calling, or purpose in life, in order to become like a star within the universe — occupying a time and position in space, yet distinctly individual. Aspects of Thelema and Crowley’s thought in general inspired the development of Wicca and, to a certain degree, the rise of Modern Paganism as a whole, as well as chaos magick and some variations of Satanism.

Note that Aiwass is described only as “the minister of Hoor-paar-kraat,” who according to Crowley represents the Higher Self, the Holy Guardian Angel. As Crowley writes in his Confessions: “We are forced to conclude that the author of The Book of the Law is an intelligence both alien and superior to myself, yet acquainted with my inmost secrets; and, most important point of all, that this intelligence is discarnate.”

William James around this time is inaugurating what would later be called “constructive postmodernism.” A reaction against (or evolution of) certain tendencies of modernism. For example, rejecting not modern science as such but only “scientism” according to which only the data from natural sciences are permitted a role in the construction of our worldview. Rejecting modernism’s individualism, anthropocentrism, patriarchy, mechanization, economism, consumerism, nationalism, militarism. It’s a sf-ish perspective, really.

Unlike the deconstructive postmodernism with which we’d become familiar in the 1960s-onward, James’s (and Peirce’s, Bergson’s, and Whitehead’s) constructive postmodernism doesn’t want to abolish notions of the human self, historical meaning, and truth as correspondence — though it does challenge/evolve these. Even more shocking, their constructive postmodernism revives certain aspects of pre-modern rationality — divine reality, cosmic meaning, enchanted nature. It’s a return of sorts to organicism. This philosophy accepts non-sensory perception — which isn’t necessarily telepathy, etc. (though it’s willing to consider it).

Modern philosophy rejects panexperientialism — the view that conscious experience [note: not thought] is fundamental and ubiquitous. Note here that while the panpsychist holds that mentality is distributed throughout the natural world (in the sense that all material objects have parts with mental properties) she needn’t hold that literally everything has a mind, e.g., she needn’t hold that a rock has mental properties (just that the rock’s fundamental parts do). Panexperientialism attributes some degree of real (self-determining) freedom to al individuals — including nonhuman individuals. Nonliving things are not devoid of experience. Nature, for modern science (though not for premodern scientists like Newton), is nonanimistic and mechanistic. Mechanism, of course, supported the modern desire to systematically dominate nature for human benefit. Constructive postmodernist thought offers panexperientialism as a hypothesis.

Sensory perception is not our only means of perceiving the world beyond our present experience. In fact, sensory perception might not even be our primary means of perception. James, being a pragmatic American (and philosophical pragmatist) was forever resisting philosophical systems that dismiss the lessons of daily experience. Meanwhile, modern philosophy tends to insist that sense-data are constructed by the perceiver. Constructive postmodernists suggest that the most basic means of perception may be a nonsensory mode. A direct, unmediated (nonsensuous), unconscious “prehension” of remote (beyond our bodies) actualities happens all the time; if it becomes conscious, then we’re talking about phenomena such as clairvoyance or telepathy. Obviously this is of sf interest.

We have experiences that are not simply culturally produced, according to Peirce and James. We have a presensory, prelinguistic, preconscious apprehension of reality. These are vague intuitions, usually on the fringes of awareness. A bottom layer, if you will, of human thought and experience.

William James’s groundbreaking essays on “pure experience” are published in 1904–5. James’s fundamental idea is that mind and matter are both aspects of, or structures formed from, a more fundamental stuff—pure experience—that (despite being called “experience”) is neither mental nor physical. Pure experience, James explains, is “the immediate flux of life which furnishes the material to our later reflection with its conceptual categories… a that which is not yet any definite what, tho’ ready to be all sorts of whats…”. That “whats” pure experience may be are minds and bodies, people and material objects, but this depends not on a fundamental ontological difference among these “pure experiences,” but on the relations into which they enter. Certain sequences of pure experiences constitute physical objects, and others constitute persons; but one pure experience (say the perception of a chair) may be part both of the sequence constituting the chair and of the sequence constituting a person. Collected in the posthumous 1912 volume Essays in Radical Empiricism.

Rudolf Steiner’s Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the Cosmos. As a starting point for the book — the first expression of what will later be named anthroposophy — Steiner quotes Goethe’s description of the method of natural scientific observation. And also Steiner’s How to Know Higher Worlds (1904–5); and the lectures (1904–1908) that will become Cosmic Memory (about Atlantis, among other things).

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin