RADIUM AGE: 1902

By:

May 1, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the cultural era of the Nineteen-Oughts begins c. 1904. So the first few years of the Twentieth Century should be regarded as a kind of interregnum between sf’s Scientific Romance era and the Radium Age. As we look at the years 1900–1904, say, we will find elements of both eras intermingling; and all traces of the Scientific Romance era will not vanish even after 1904.

By 1902, Munsey’s pulp magazine The Argosy was third in circulation amongst American magazines.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1902, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: DEATH RAY (in G. Griffith’s “Masters of the World”) | MIND CONTROL | OUTWORLD (a John Buchan coinage).

- Alfred Jarry‘s novella Le surmâle (The Supermale), a comic fantasy featuring a Superman who, nourished on superfood, wins an extraordinary bicycle race against a six-man team and performs astonishing feats of erotic endurance, published posthumously.

Jarry — writing on the cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries — gives us one of the very first Radium Age supermen. In the nineteenth century, one is given to understand, perhaps no scientific theory sparked more occult thought than organic evolution. True, organic evolution is often construed as a counterweight to the idea that humankind has a divine origin. But the prospect of humankind’s unlimited evolutionary ascent within the cosmos fired the imagination of scientists and occultists alike. Sure, the evolutionary process, being blind and non-teleological, does not aim for improvement or perfection; however, its theorists often could not refrain from dramatizing it. In the closing paragraph of Origin of Species, Darwin insisted that there is a grandeur in this [evolutionary] view of life, and elsewhere he portrayed natural selection as infinitely more sagacious than man, and all seeing and infinitely wise. Huxley, Darwin’s bulldog, suggested that thanks to Darwin, humankind could now knowingly evolve and thereby outmaneuver a great deal of unnecessary hardship and catastrophe.

- George Griffith’s The Lake of Gold: A Narrative of the Anglo-American Conquest of Europe (December 1902-July 1903 Argosy; as a book, 1903). American industrialists, financed by the eponymous lake at the heart of a South American volcanic crater, bring about an equitable balance between capital and workers in America — then mount an Invasion of Europe to gain the same goal there. The only Griffith extravaganza published in America, where it attracted little attention.

- H.G. Wells‘ “The Loyalty of Esau Common.” A fragment originally written as a companion piece to “The Land Ironclads,” it shows much more clearly than the more famous story the conflicts that were straining Wells’s own loyalties and thoughts at this time. Esau Common, a gifted prole in a rigidly aristocratic and militarily traditional society, resists the temptation to defect to a more just and reasonable neighboring country which has modernized warfare. The story lacks a conclusion.

- H.G. Wells‘ “The Queer Story of Brownlow’s Newspaper.” Wells elaborates further the kind of temporal-spatial anomalies he entertained in such early works as “The Story of Davidson’s Eyes” and “The Platter Story.” The story takes place on 10 November 1931 and opens with the protagonist accidentally being delivered a newspaper dated 10 November 1971. The story is mainly a description of the contents of the newspaper, with Wells taking the opportunity to predict, e.g., lower birth rates, an emphasis on psychological motivation in fiction, geothermal energy, and wider coverage of scientific news. Hints at some form of world government.

- Owen Oliver’s “The Man Who Could Not Forget” — in The London Magazine. The author’s real name was Joshua Albert Flynn. Flynn was a British economist.

- Winnifred Harper Cooley’s “A Dream of the Twenty-first Century” — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Laura Dayton Fessenden’s “2002”: Childlife One Hundred Years from Now — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Eva L. Ogden’s “The Cold Storage Baby” — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Rudyard Kipling’s “Wireless” — in which amateur radio experiments make communication across time possible, linking a chemist’s-shop assistant and John Keats. It was first published in Scribner’s Magazine in 1902, and was later collected in Traffics and Discoveries.

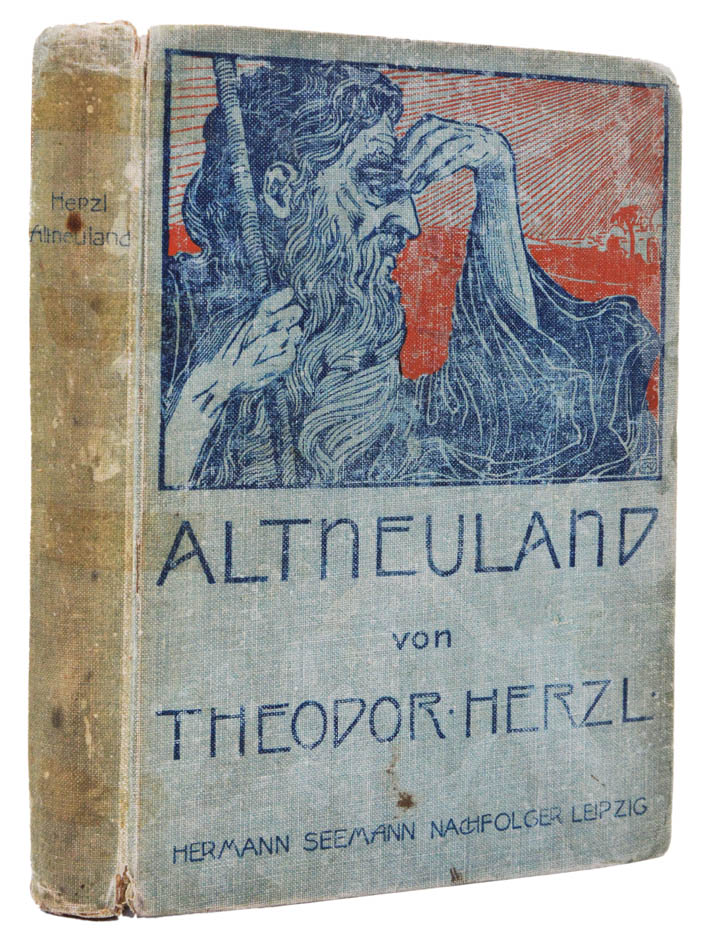

- Theodor Herzl’s Altneuland (The Old New Land) — a literary expression of Herzl’s desire for the foundation of a home country for the Jewish diaspora. It was translated into Yiddish in 1902, and into Hebrew the same year as Tel Aviv — a name then adopted for the city founded in 1909. The novel tells the story of Friedrich Löwenberg, a young Jewish Viennese intellectual, who, tired with European decadence, joins an Americanized Prussian aristocrat named Kingscourt as they retire to a remote Pacific island (it is specifically mentioned as being part of the Cook Islands, near Rarotonga) in 1902. Stopping in Jaffa on their way to the Pacific, they find Palestine a backward, destitute and sparsely populated land, as it appeared to Herzl on his visit in 1898. Löwenberg and Kingscourt spend the following twenty years on the island, cut off from civilization. As they stop over in Palestine on their way back to Europe in 1923, they are astonished to discover a land drastically transformed.

- W.F. Alexander’s “My Cousin’s Airship, A Tale of 1950” — weak sensationalism.

- Howard Austin’s dime novel Among the Fire Worshippers — a lost race descended from the Aztecs, in Mexico. Typical stuff.

- Mrs. Campbell Praed’s The Insane Root. A theosophical novel I’d like to know more about.

- J.K. Bangs’s Bikey the Skicycle and Other Tales of Jimmieboy — sf fantasy stories for small children by a US author best known for A House-Boat on the Styx (1895). Bleiler calls it “feeble.”

- Frank Harris’s “The Charlatan” — collected in Beyond the Gaslight: Science in Popular Fiction 1895–1905.

- Oskar Hoffmann’s Mac Milfords Reisen im Universum. The first book in the publisher’s popular “Kollection Kosmos,” a dime-novel type series (1902-1903) describing Mac Milford’s “voyages into the universe.”

- John Buchan’s story collection The Watcher by the Threshold and Other Tales). The Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction credits Buchan with here coining the term “outworld”: “In this savage out-world a man stood for a man.” It’s from the 1901 story “Fountainblue.” Not a proto-sf story, at all! The collection does include, however, an 1899 proto-sf Lost World novella first published in Blackwood’s Magazine. The story is sometimes cited as an influence on Robert E. Howard and other pulp writers of Howard’s era. Serialized here at HILOBROW.

- Edwin Pallender (pseudonym of Lancelot Francis Sanderson Bayly)’s The Adventures of a Micro-Man. Professor discovers microgen gas which has the power of rendering animate or once animate things extremely small. The gas is accidentally released and four humans, reduced to about one-thousandth of their normal sizes, face perils, indoors and out in the garden, from normally tiny things that have now become menaces. “Competent commercial work exploiting an idea systematically.” – Bleiler

- Mark Twain’s “The Double-Barrelled Detective Story” — a Sherlock Holmes parody; one of the protagonists has modest extrasensory powers.

ALSO: Rutherford and Soddy discover that radioactivity is associated with changes inside the atom; they formulate the exponential decay law. (Classical Newtonian mechanics could not explain such phenomena; quantum mechanics was developed to replace it.) Poincaré’s La science et l’hypothèse discusses non-Euclidean geometry and the Fourth Dimension; Poincaré, who argued that intuition (not logic) was the life of mathematics, argues here that “For a superficial observer, scientific truth is beyond the possibility of doubt; the logic of science is infallible, and if the scientists are sometimes mistaken, this is only from their mistaking its rule.” Oliver Heaviside states the existence of an atmospheric layer which aids the conduction of radio waves. Scott, Shackleton and Wilson reach the furthest southern point reached thus far by humankind. Lombroso’s “Why Criminals of Genius Have No Type.” Trotsky (shown above) escapes from a Siberian prison and settles in London. Aleister Crowley, heir to a brewing fortune and a “flamboyant, bisexual drug fiend with a fascination for the occult,” co-leads the first-ever expedition to reach the summit of K2, the second highest mountain in the world. Remains of the second Tyrannosaurus rex specimen, the first recognized as such, are excavated in Montana. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, Andre Gide’s The Immoralist (influenced by Wilde, Baudelaire, Nietzsche), Kipling’s Just-so Stories, Chekhov’s Three Sisters. Owen Wister’s The Virginian, modeled on a Walter Scott-style knightly romance, is the prototypical early fictional Western. Yeats’ The Celtic Twilight, Croce’s Philosophy of the Spirit (Volume I, on aesthetics). Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (argues that mutual aid has pragmatic advantages for the survival of human and animal communities and, along with the conscience, has been promoted through natural selection); note that during this period the revolutionary left is closer to the ideas and the mood of anarcho-syndicalism than it is to that of classical Marxism. Americans during this period coming to terms with a rapidly changing political economy, one newly dominated by large corporations, national markets, global aspirations, and urbanized living.

William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience puts religious beliefs and experiences to the test of their role in psychological health or morbidity — a Nietzschean effort. His interest is in how religion has been experienced on a private, emotional level at various times throughout history. The book is notable for its focus not on truths derived strictly from material phenomena but on the truth as it is experienced. James does not shrink from discussion of higher forms of consciousness: “Our normal waking consciousness… is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the flimsiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different,” he claims here. “We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus and at a touch they are all there in all their completeness… No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.”

H.G. Wells, writing in the science journal Nature in February 1902: “It is possible to believe that all the past is but the beginning of a beginning, and that all that is and has been is but the twilight of the dawn. It is possible to believe that all that the human mind has ever accomplished is but the dream before the awakening. We cannot see, there is no need for us to see, what this world will be like when the day has fully come. We are creatures of the twilight. But it is out of our race and lineage that minds will spring, that will reach back to us in our littleness to know us better than we know ourselves, and that will reach forward fearlessly to comprehend this future that defeats our eyes. All this world is heavy with the promise of greater things, and a day will come, one day in the unending succession of days, when beings, beings who are now latent in our thoughts and hidden in our loins, shall stand upon this earth as one stands upon a footstool, and shall laugh and reach out their hands amidst the stars.”

Also in 1902: Simon Newcomb’s essay “The Fairyland of Geometry” in the January 1902 issue of Harper’s. See 1900 for more on Newcomb, who helped popularize connections between the mathematical and spiritualist notions of a fourth dimension.

Around 1900, advertising guru James Walter Thompson published a housing advertisement explaining trademark advertising. This was an early commercial explanation of what scholars now recognize as modern branding and the beginnings of brand management. Between 1902–1910 George B. Waldron, working at Mahin’s advertising agency, used tax registers, city directories and census data to show advertisers the proportion of educated versus illiterate consumers and the earning capacity of different occupations in what is believed to be the first example of demographic segmentation of a population. Within little more than a decade, Paul Cherington had developed the ‘ABCD’ household typology – the first socio-demographic segmentation tool. In 1902, the University of Michigan offered what many believe to be the very first course in marketing. Other universities soon followed, including the Harvard Business School (which opened in 1908). Prior to the emergence of these marketing courses, marketing was not recognized as a discipline in its own right.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin