RADIUM AGE: 1920

By:

September 4, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

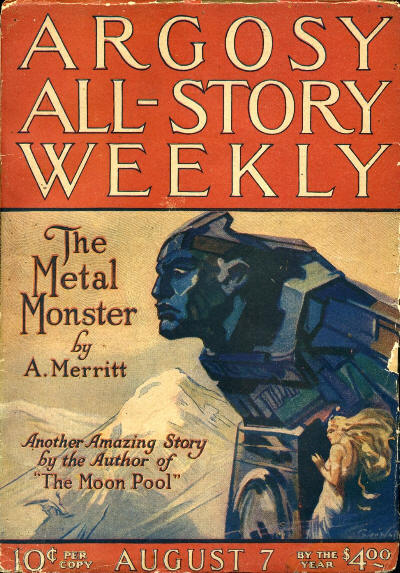

Argosy and All-Story Weekly combine and become Argosy All-Story Weekly.

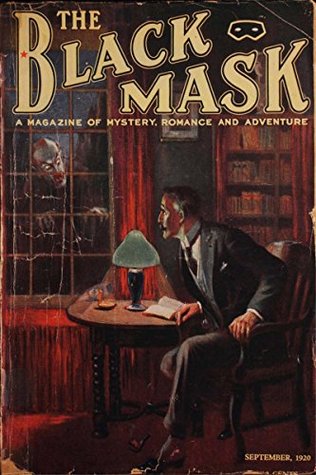

One of the most important of all detective pulps was Black Mask (April 1920 — July 1951), which would serialize Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon between Sept. 1929 and Jan. 1930, while Chandler would make his authorial debut in the Dec. 1933 issue. Also in 1920, Bob Davis would leave the Munsey magazines, the end of an era.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1920.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1920, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: INNER SPACE (the human mind; the innermost parts of one’s psyche) | MOON ROCKET | ROBOT (in Karel Čapek’s RUR[:] Rossum’s Universal Robots) | WORLD-BUILDING (in A. S. Eddington’s Space, Time & Gravitation) |

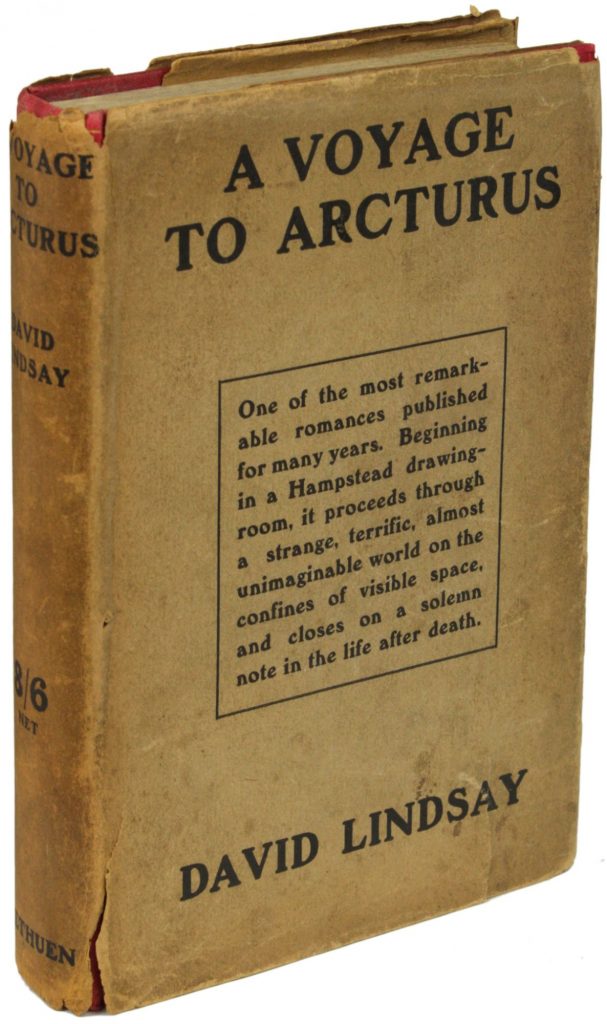

- David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus (1920). An adventurous Scot, Maskull, encounters a semi-divine trickster figure, Krag, who whisks him from Earth to the planet Tormance, orbiting Arcturus. Reality is fluid, on Tormance — which turns out to be less an actual planet than a kind of proving-ground of the soul. Each chapter introduces a new philosophical system, religious idea, and concept of the true nature of the world — and then, having persuaded Maskull (and the reader) to believe in these things, mocks us for doing so. (C.S. Lewis on Lindsay: “He is the first writer to discover what ‘other planets’ are really good for in fiction… To construct plausible and moving ‘other worlds’ you must draw on the only real ‘other world’ we know, that of the spirit.”) Maskull is tormented by Crystalman, who bedevils humankind with comforting illusions and false pleasures. Falseness, it transpires, is winning the war against truth; only Krug, who maintains his sense of humor, and who claims to be known on Earth as “Pain,” can hold his own in the fight. Maskull’s trials and tribulations release his authentic self: Nightspore, who must return to Earth and save more souls from Crystalman’s clutches! Fun fact: A Voyage to Arcturus has been described as Calvinist (because pleasure is rejected in favor of instructive pain), Gnostic, Nietzschean, and psychedelic. Ballantine Books’s influential Adult Fantasy series rescued the book from obscurity in 1968. “One of the most extraordinary works of literature, let alone fantasy, ever written.” – Colin Greenland, Scottish Fantasy Literature. “A classic allegorical romance in which the landscapes and inhabitants of the planet Tormance provide an externalization of the moral and metaphysical questions that preoccupied the author.” – Anatomy of Wonder. “The metaphysics that is gradually elaborated is basically a transformed evolutionary theory that applies a harsh metaphorical Darwinism to the business of personal intellectual development.” – Barron (ed), Fantasy and Horror.

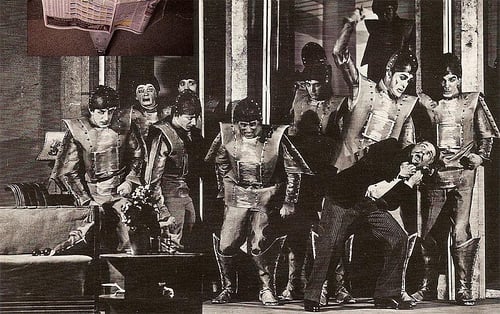

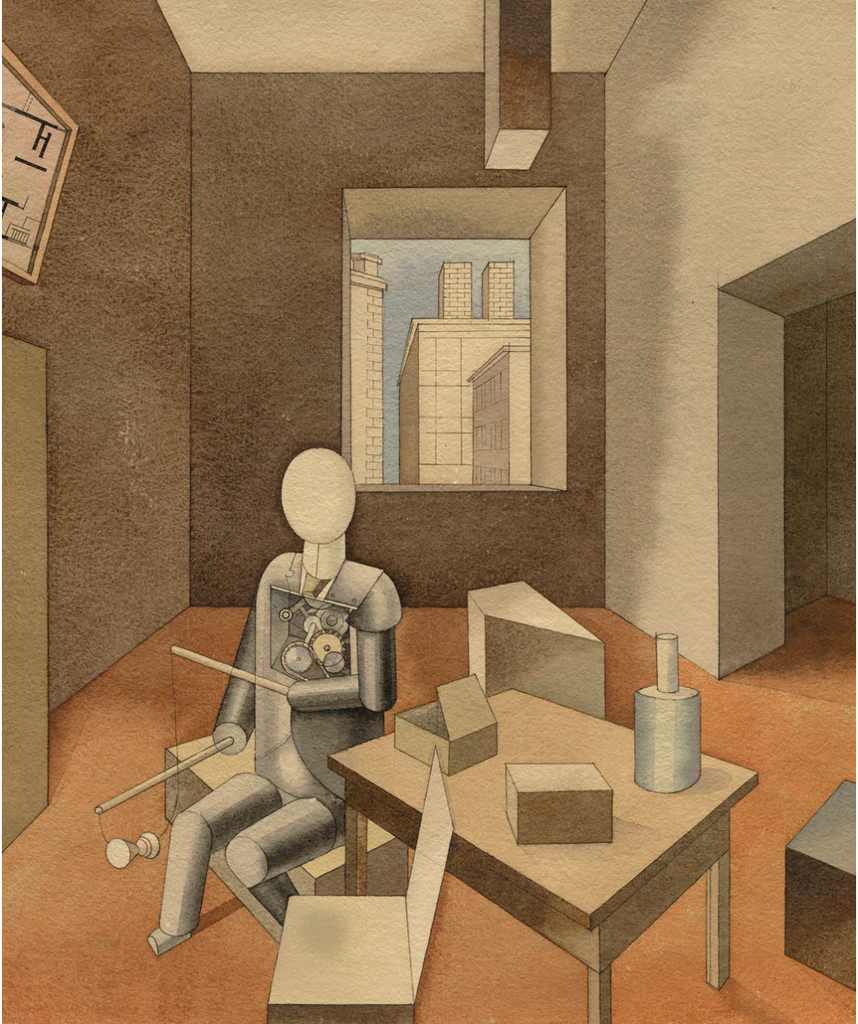

- Karel Čapek’s R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots (1920–1921). In the 1960s, the factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots, has shipped hundreds of thousands of “Robots” — biological humanoids designed for cheap labor — around the world. The Robots, which have a limited life span, are supposedly soulless. Not so, claims Helena Glory, a liberal activist who marries the factory’s GM (who envisions a utopia in which humans won’t have to do any work). At Helena’s urging, R.U.R.’s scientists develop Robots tricked out with extra humanity… at which point they rise up and exterminate humankind. In an epilogue, Alquist, R.U.R.’s construction engineer and the last surviving human, give his blessing to two new-model Robots, Primus and Helena, who have discovered love. Fun fact: The term robot, coined by Čapek’s brother Josef, who (like Karel) feared the unlimited power of corporations, comes from the Czech for “serf labor.” Reissued by Penguin Classics.

- T.S. Stribling’s “The Green Splotches” (1920) — appears in the 1943 anthology The Pocket Book of Science Fiction, edited by Donald A. Wollheim.

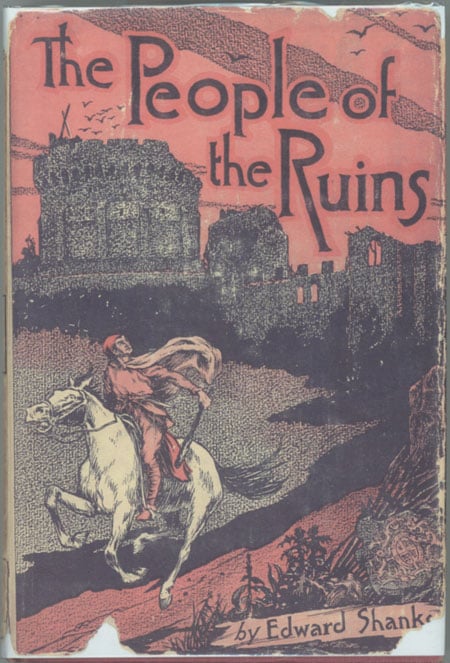

- Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins (1920). A proto-Idiocracy satire on H.G. Wells’s utopian novels. Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — on the eve of a new Dark Age! England has become a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress (“He had held the comfortable belief that mankind was advancing in conveniences and the amenities of life by regular and inevitable degrees”), Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful (“We used to feel that we were living on the edge of a precipice — every man by himself, and all men together, lived in anxiety”). That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point Tuft sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction. Note that although the “future war” subgenre of proto-sf flourished from c. 1870-1914, WWI caused a hiatus. This book, along with Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (1922), marks a return of sorts to the subgenre, though now with much less excitement and more foreboding. “The first of the many British postwar novels that foresee Britain returned to barbarism by the ravages of war.” — Anatomy of Wonder, Neil Barron, ed. (1976). MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series will reissue this title.

- Pierre Benoit’s Atlantida (l’Atlantide). Translated by Mary C. Tongue and Mary Ross, 1920 (US edition shown here). Lost colony of Atlantis survivors in the Sahara. “Well imagined … The narrative is fast-moving and holds one’s interest as well. All in all, perhaps the best of the older Atlantis fictions.” — Bleiler.

- Maurice LeBlanc’s Le Formidable Evènement (1920); 1922 in English, as The Tremendous Event). In the near future, an earthquake creates a new landmass linking England and France. Chaos ensues — rivers are blocked, coastal cities damaged, ships shipwrecked. Although bands of vicious criminals roam the newly exposed land, looting the shipwrecks, an English aristocrat and his daughter, Isabel, must risk these dangers in order to retrieve their family treasure, which was on one of the stranded ships. Isabel is captured, and faces a fate worse than death. English and French military forces, meanwhile, are converging — both intent on claiming the new territory. Simon Dubosc, a handsome Frenchman in love with Isabel, joins forces with a band of American Indians (!) who happened to be visiting, and rides across the desert-like terrain to Isabel’s rescue. Fun fact: Leblanc is best known for his stories about Arsène Lupin.

- Vachel Lindsay’s The Golden Book of Springfield, is an early exercise in Medieval Futurism. Springfield, Illinois has become a walled garden city whose growth has been symbolically made possible by the “Amaranth Apple” presented to Springfield’s original founder by Johnny Appleseed himself… the effect of this apple being directly contrary to that of the Edenic apple that engendered man’s first disobedience. A racially mixed citizenry – the protagonist of the tale is herself part Native American, part African, part European – share goods and duties, keep the industrialized outer world at bay, and express freely their individual genius.

- Dr. C.E. Linton’s The Earthomotor and Other Stories. Linked short stories of exploration (journey to earth’s hollow interior, flight to the moon, etc.) utilizing the “Earthomotor,” a burrowing machine, and the “Arctic Bell,” a flying boat. Much of the narrative is set in Alaska and the Arctic region.

- Edgar Wallace’s Green Rust. Mystery thriller in which German scientist develops a poison to destroy the world’s wheat crops.

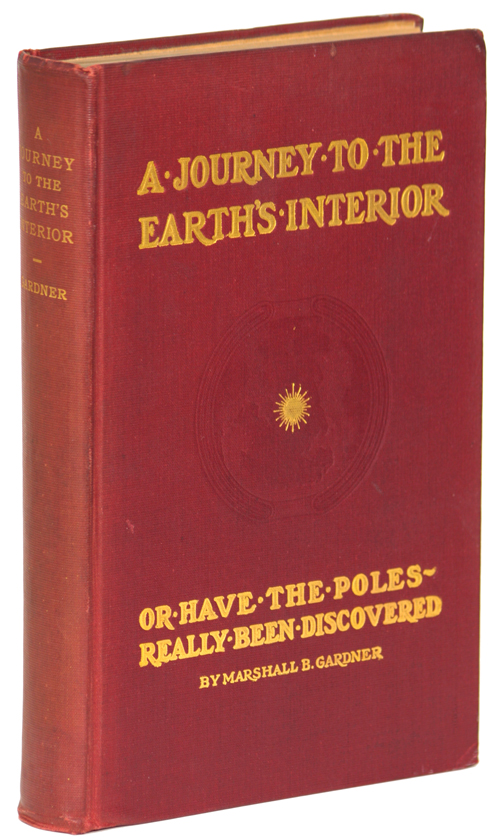

- Marshall B. Gardner’s A Journey to the Earth’s Interior, or Have the Poles Really Been Discovered. This isn expanded version of a small, 1913 privately publishe book. A very detailed explanation and defense of the author’s hollow earth theory. A chapter is devoted to an imaginary journey through the earth — into one polar opening and out through the other. Interesting illustrations, some in color. Gardner was in charge of maintenance of machinery for a large corset company in Aurora, Illinois.

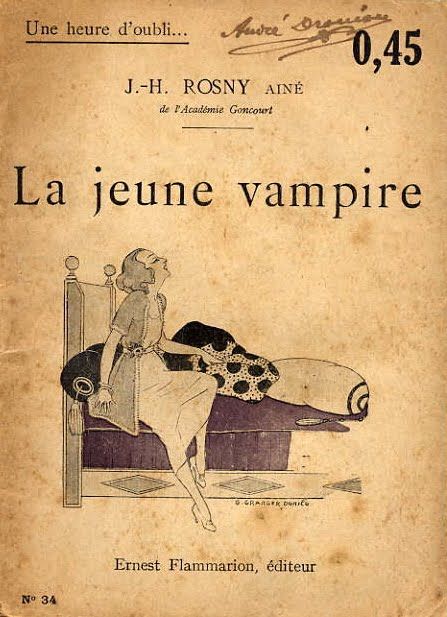

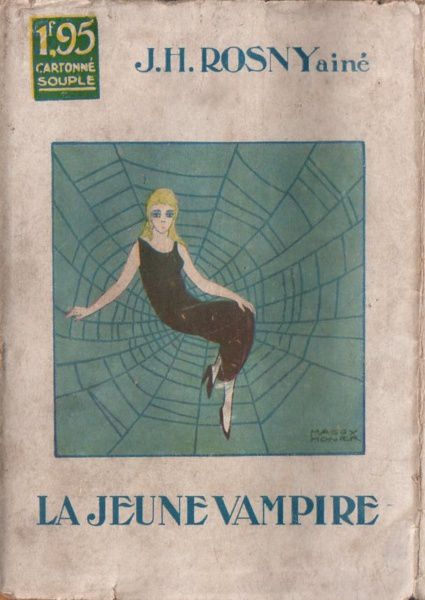

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s La Jeune Vampire [The Young Vampire]. A London girl is possessed by an extra-dimensional entity which mutates her body and turns her into a living vampire. The first time that vampirism was described as a genetic mutation, transmissible by birth.

- Mondrian’s Le Neo-Plasticisme (Principe général de l’equivalence plastique), published in 1920 by Editions de l’Effort Moderne, is dedicated to “the man of the future.”

- G.K. Chesterton’s “The Finger of Stone” — a case of abnormally rapid petrification. Silly.

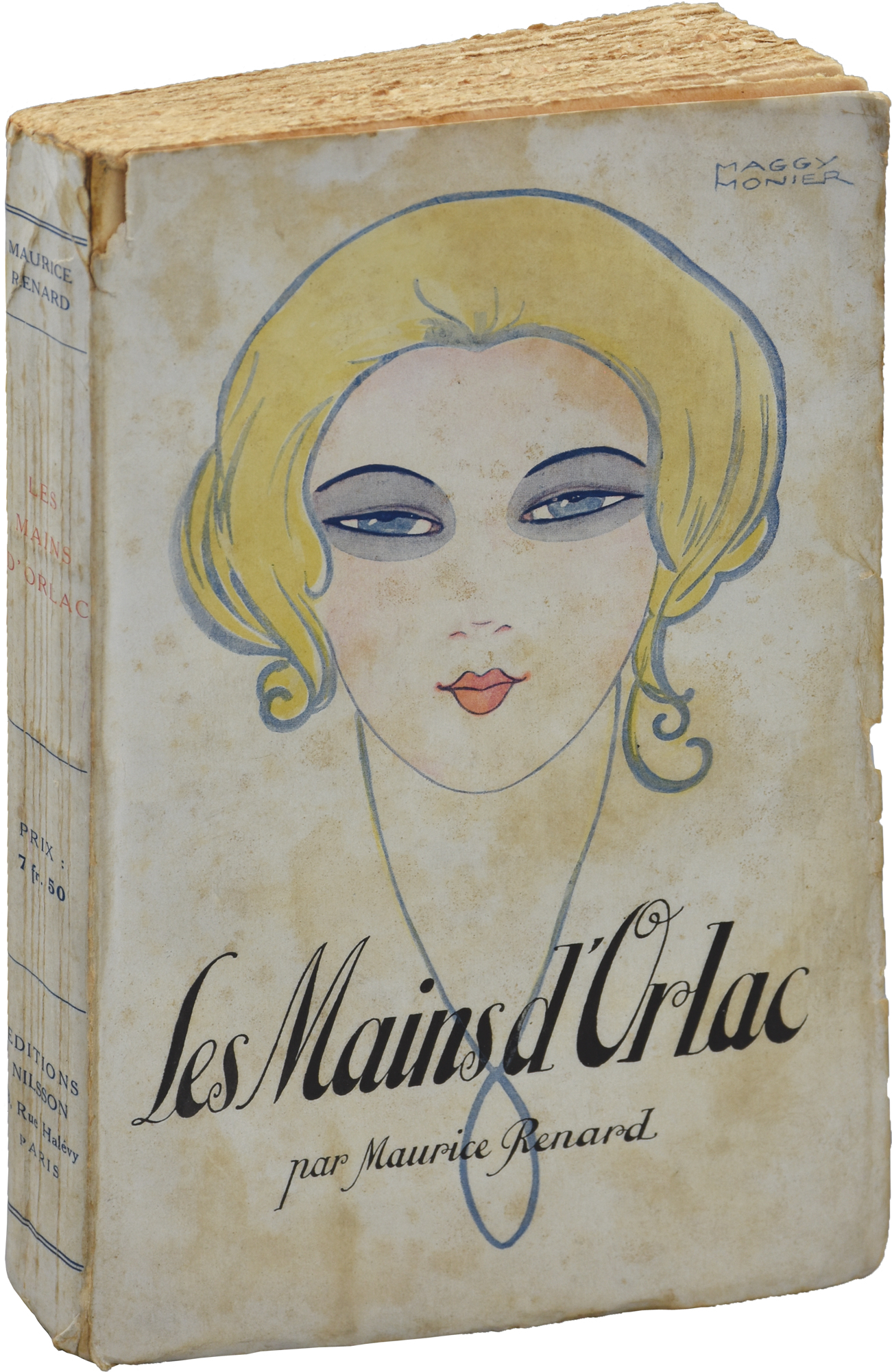

- Maurice Renard’s Les mains d’Orlac (15 May-12 July 1920 L’Intransigeant; 1921 as a book; trans Florence Crewe-Jones as The Hands of Orlac 1929. It remains Renard’s most popular and most translated novel, but its use of futuristic medical technology never dominates a narrative focused on the Gothic consequences of a hand transplant. A celebrated pianist loses his hands in a train wreck, and has them surgically replaced with those of an executed murderer; then he begins to assume the personality of his appendages’ psychopathic donor. The book was made into a movie on several occasions: the two most famous being the one in 1926 by Robert Weine (creator of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) with Conradt Veidt as Orlac, and the one in 1935 by Karl Freund with Peter Lorre in the title role.

- Yakov Okunev’s The Coming World 1923–2123. Utopian affirmation for supposedly scientific adjustments of sexual selection. The genius of anabiosis, Professor Moran, sends to the future his deadly daughter Eugenia and the reflective intellectual Vikentyev … The revolutionary storm sweeps away the last capitalists of America … What will come to an end with unprecedented social and medical experiments? What will the people of 1923 see in the year 2123? See Drozdz’s essay on “Parodies of Authority in the Soviet Anti-Utopias from 1918-1930.”

- A. Merritt’s The Metal Monster. Serialized (Argosy All-Story Weekly) in eight parts in 1920, revised in 1927 as (the eleven-part) The Metal Emperor. The titular monster/emperor is an inorganic alien being with a hivelike organization. Moskowitz calls this “a tour de force, one of the most remarkable sf stories ever written.” Frank Cioffi tells me that this one is “the most distinctive of Merritt’s novels, and the one most relevant to today’s concerns.” Published in book form in 1940.

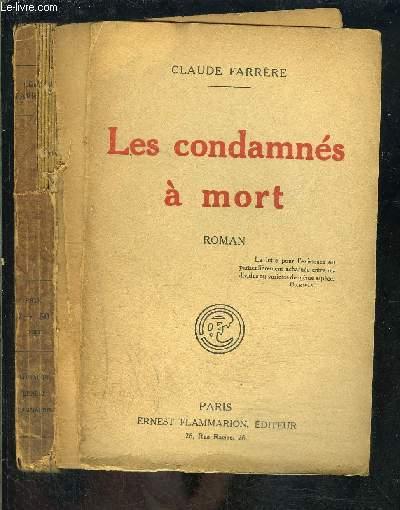

- Claude Farrere’s Les condamnés à mort (translated 1926 as Useless Hands). A bitter melodrama about utopia betrayed, and robots taking jobs. Renders in harsh Social-Darwinist terms a 1990s workers’ revolt as bleakly pathetic: when the workers — the “useless hands” of the English-language title — go on strike against the threat of automation, they are disintegrated by a new weapon. “Told on an almost surrealistic level; cerebral, but imaginative; far superior to the similar Metropolis by Thea von Harbou.” — Bleiler.

- E.H. Johnson’s “The Golden Vapor.” Ashley says it gives an original twist to matter-transmission stories. Publshed in Science and Invention magazine.

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s “Claimed” (6-20 March 1920 Argosy Weekly; 1966) in which an elemental being recovers an ancient artifact. Not exactly sf.

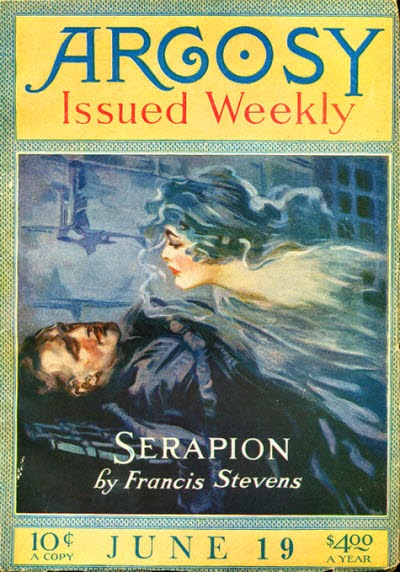

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s “Serapion” (19 June-10 July 1920 Argosy). When a seance goes awry, a man finds himself stalked by an evil which has crossed over and threatens his very soul. An exercise in cosmic horror evocative of later horror in sf.

- Garret Smith’s “The Treasures of Tantalus” (11 December 1920-8 January 1921 Argosy All-Story Weekly, which feature devices to see anything happening anywhere in the world. The morality of these is discussed, though at no great length.

- Gaston Leroux’s Aventures effroyables de M Herbert de Reinich (trans. 1922 as The Amazing Adventures of Carolus Herbert.) The exploits of a mysterious captain and his super-submarine in World War One. The first story is “Capitaine Hyx” (trans. as “The Amazing Adventures of Carolus Herbert”) and the second is “La Bataille invisible” (trans. as “The Veiled Prisoner”).

- Murray Leinster’s “The Mad Planet” (Argosy). Set in the far future of Earth after the atmosphere has been filled with carbon dioxide (partly by human burning of coal and oil, in a strange foreshadowing of global warming) and most plant and animal life has died off, leaving monstrous fungus forests and giant insects and a meek, devolved shred of the human race. The prose and attitude is terse and tough and modern. We follow Burl, a member of a human tribe, who wanders through a nightmare world of deadly spores, giant hunter spiders, killer crayfish, and foot-long army ants. Burl sporadically begins to think, and discovers the wonders of tools — specifically, spears and clubs. Along with its sequel, “Red Dust” (1921), and a much later sequel too, it would become part of the 1954 book The Forgotten Planet. Whose story is somewhat different. Gernsback reprinted both stories in Amazing in 1927. Moskowitz lavishes great praise on it in Under the Moons of Mars.

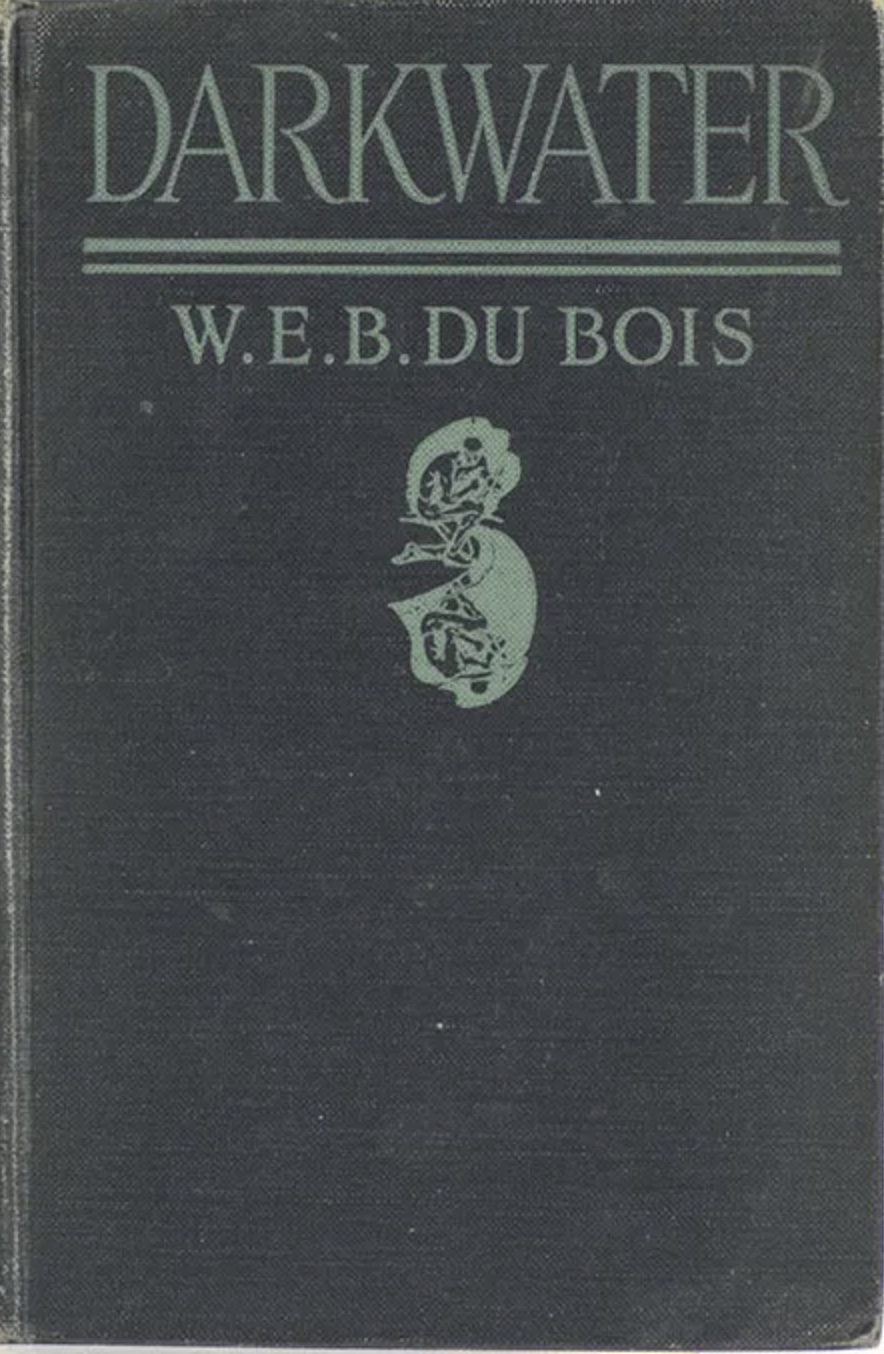

- W.E.B. Du Bois’s “The Comet.” The Black protagonist fears he may be the last man alive after he escapes from a closed vault to find Manhattan deserted after a comet has devastated the city. Eventually he encounters a white woman, but their growing empathy is terminated when her father and other white survivors enter the scene. Included in Voices from the Radium Age (MIT Press), a 2022 story collection edited by yours truly.

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “From Beyond” (w. 1920, pub. 1934). “What do we know… of the world and the universe about us? Our means of receiving impressions are absurdly few, and our notions of surrounding objects infinitely narrow. We see things only as we are constructed to see them and can gain no idea of their absolute nature. With five feeble senses we pretend to comprehend the boundlessly complex cosmos.” S. T. Joshi judges it “unlikely that ‘From Beyond’ … will ever be regarded as one of Lovecraft’s better tales”, due to “its slipshod style, melodramatic excess and general triteness of plot.”

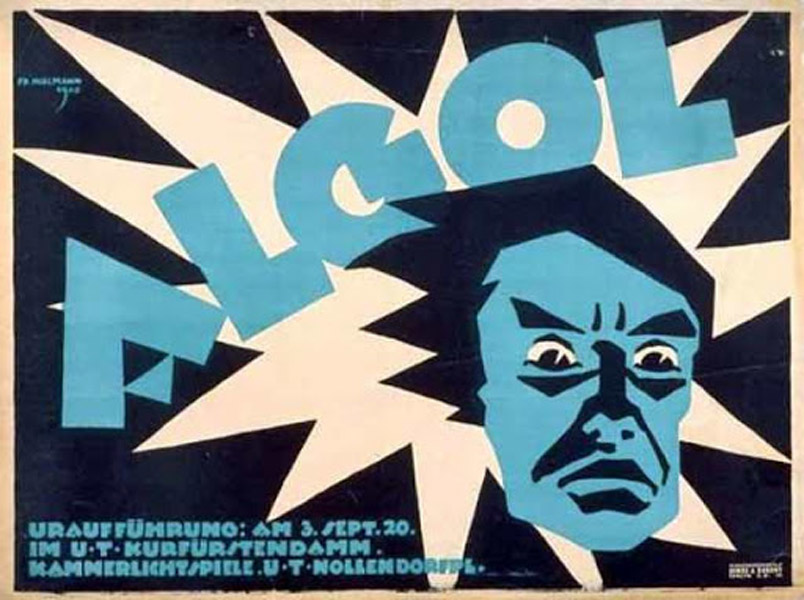

- Algol: Tragedy of Power (German: Algol. Tragödie der Macht) is a 1920 German science fiction film about an alien from the planet Algol. The film was directed by Hans Werckmeister and stars Emil Jannings and John Gottowt. The story centers on a human who is given a machine by an alien spirit which, if used, would allow him to rule the world. The sets for the movie were constructed by Walter Reimann, one of the set designers of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

- Florence L. Barclay’s Returned Empty. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mary Johnston’s Sweet Rocket. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Jeanne Judson’s The Stars Incline. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

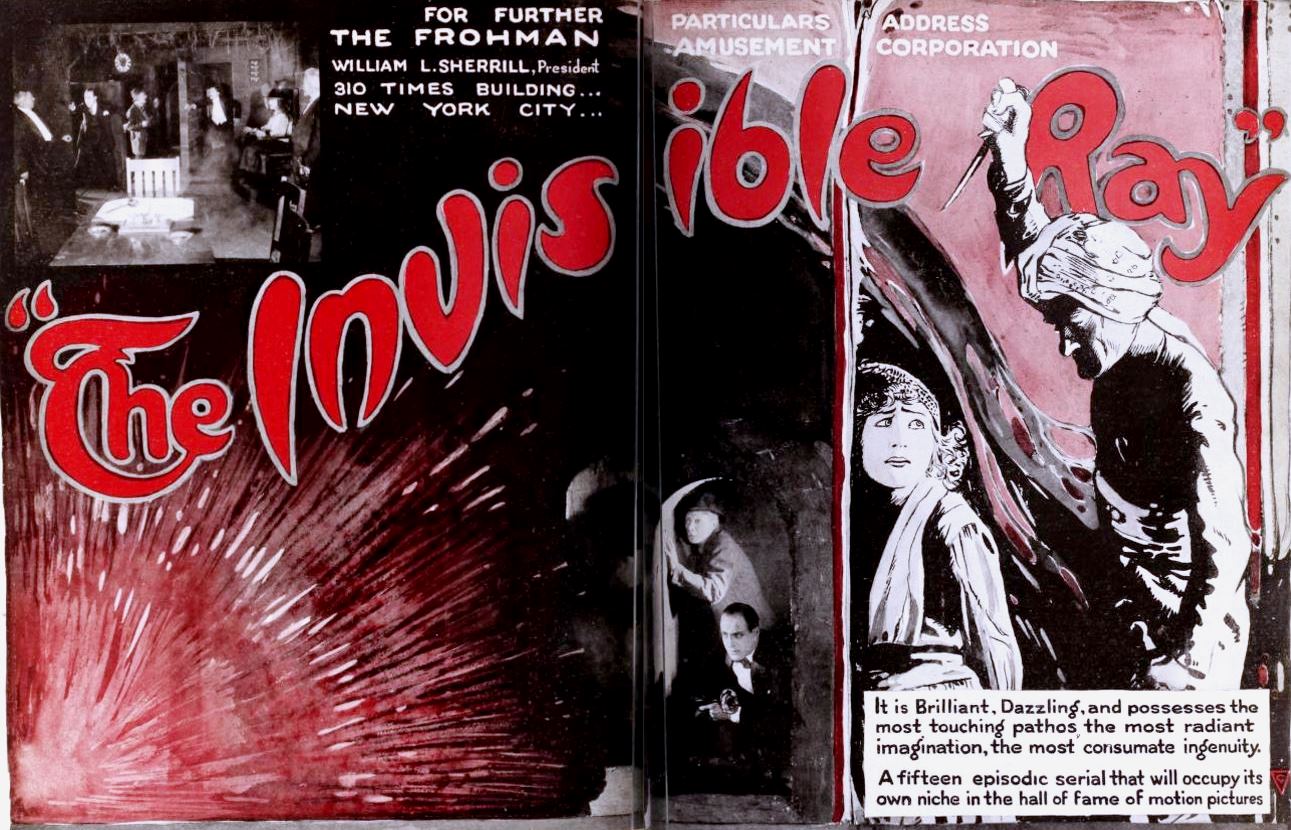

- The Invisible Ray is a 1920 American science fiction film serial directed by Harry A. Pollard. After a mineralogist discovers a ray with extraordinary powers, a group of scientists seek to use it for a criminal scheme. The serial begins with the two keys to a box that contains the source of the rays which, if concentrated, are powerful enough to destroy the world. One of the keys is hung around the neck of Mystery, a foundling girl who is the daughter of the mineralogist. The second key and the box are in unknown hands at the beginning of the serial. Jack Stone loves her, but on the night of their planned elopement Mystery is kidnapped for the key she wears, which falls at the door of the minister. She is taken to an underground chamber where she is tortured in an attempt to force her to give up her key. Jack and a friend visit a Crystal Gazer who reveals the whereabouts of Mystery. In a thrilling chase through underground chambers the young woman is rescued, only then to fall back into the hands of her enemies. Etcetera.

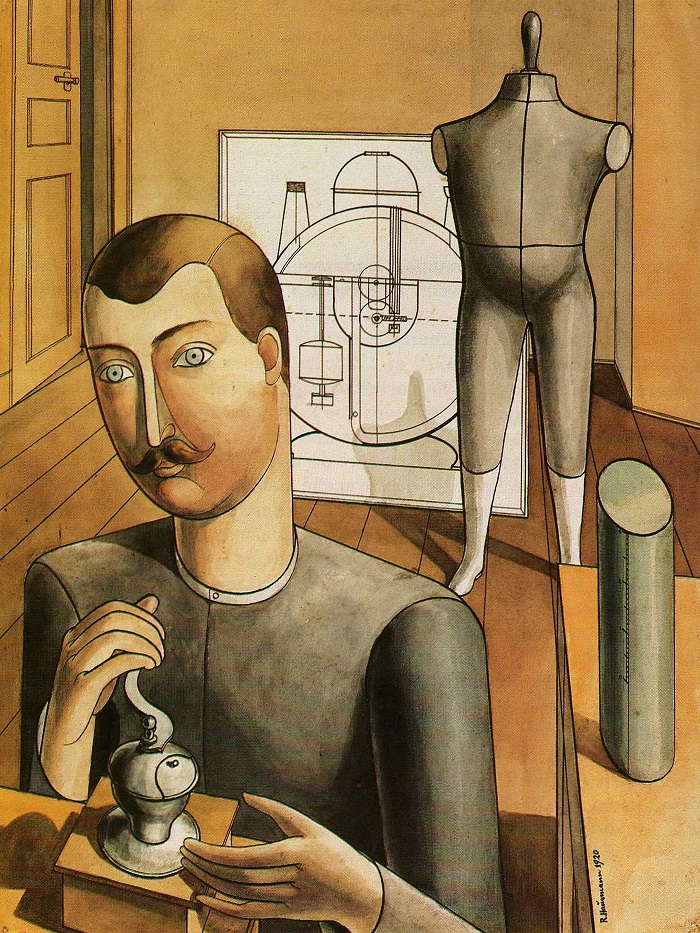

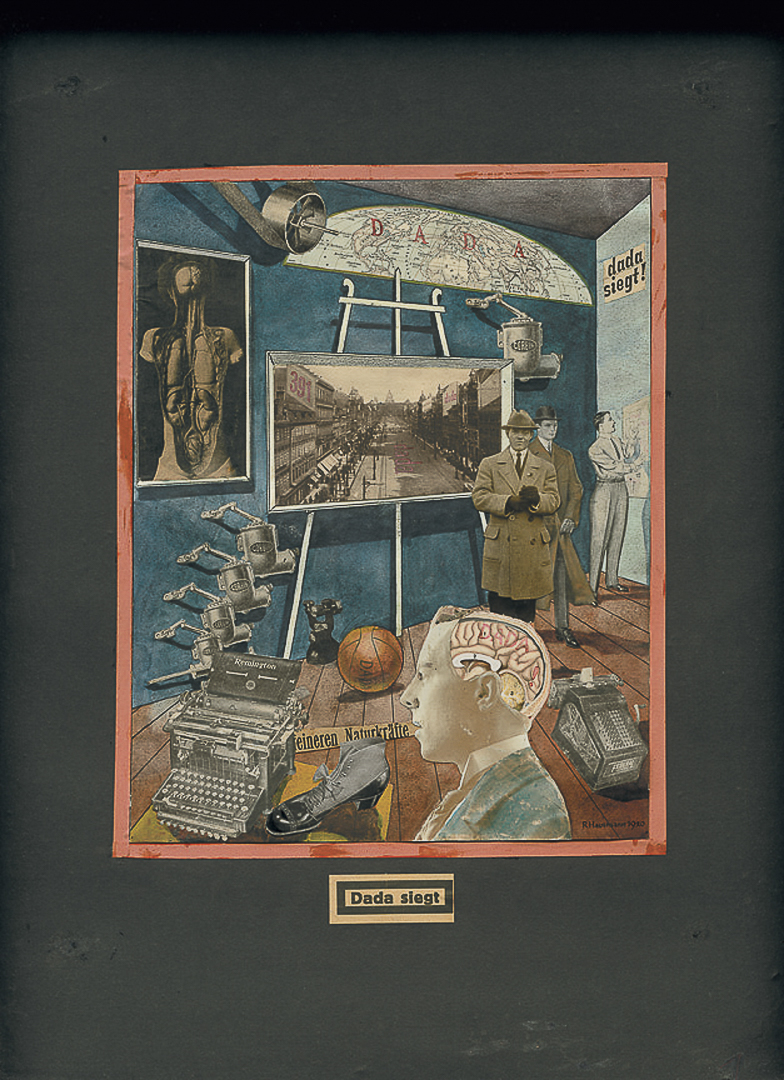

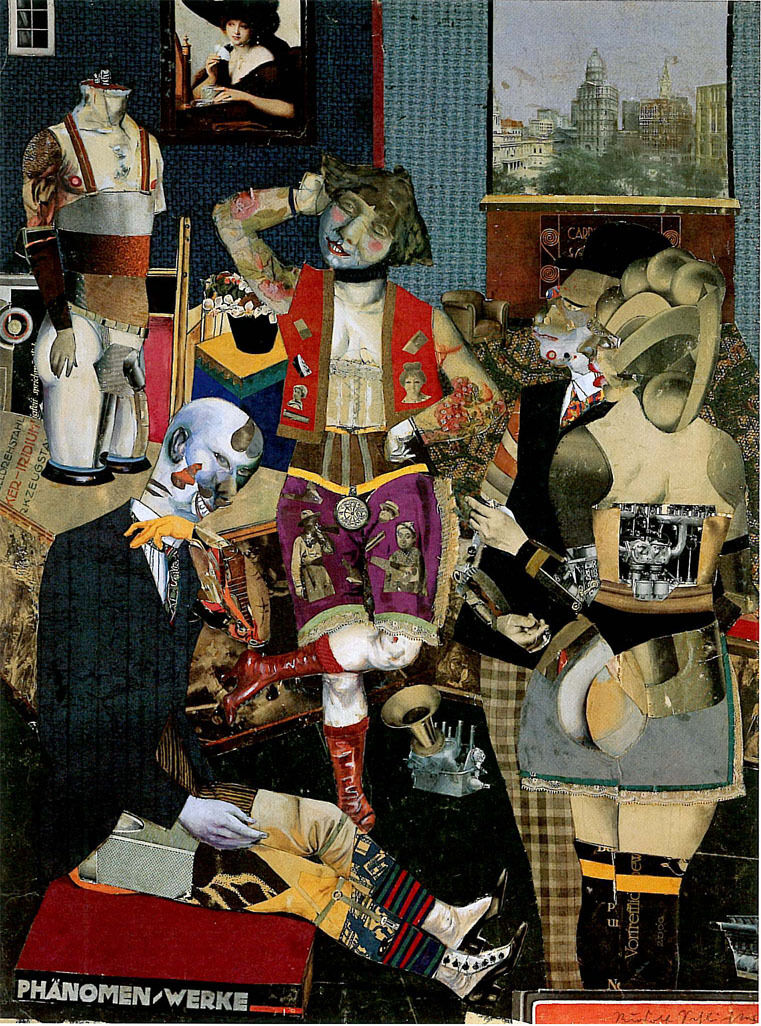

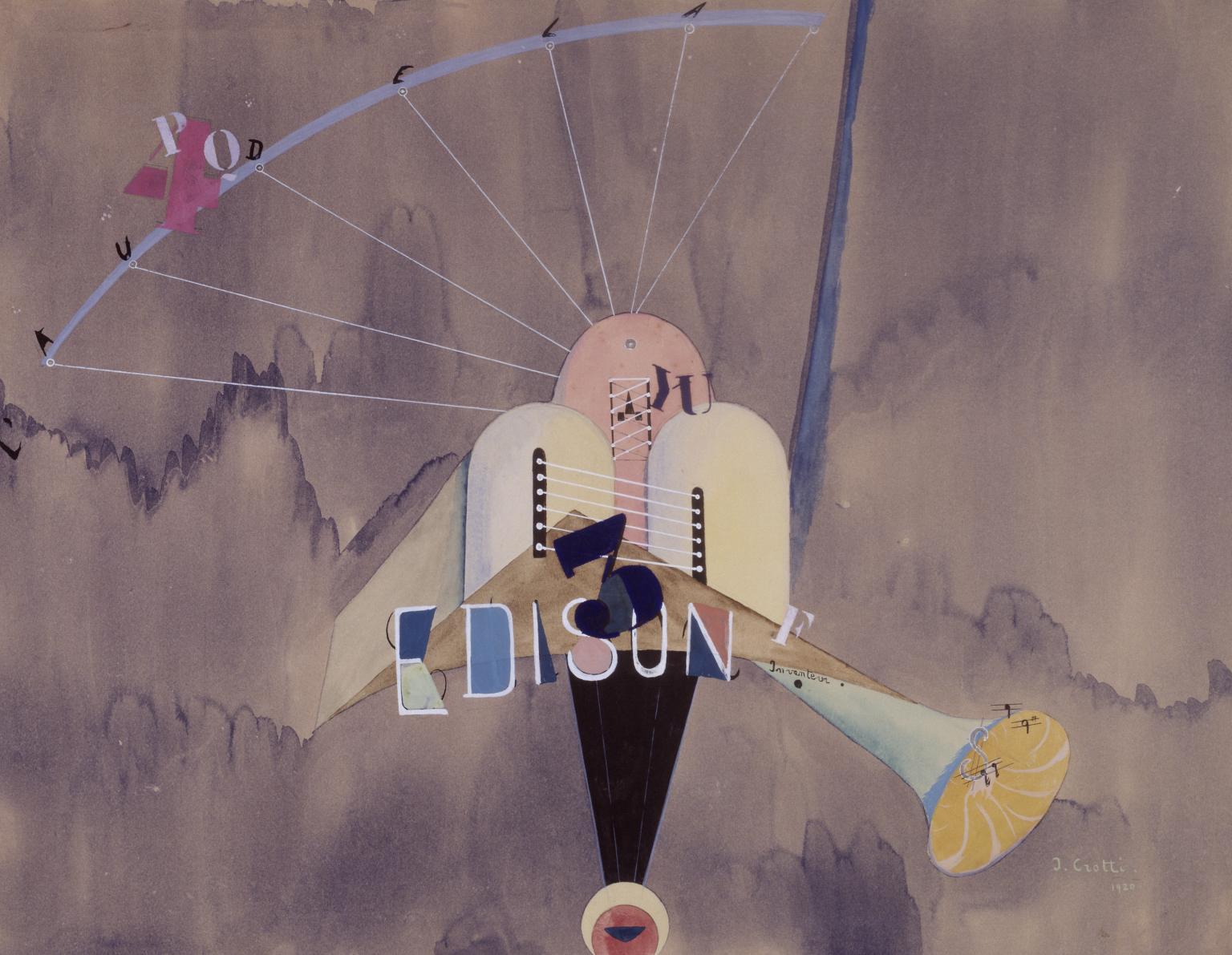

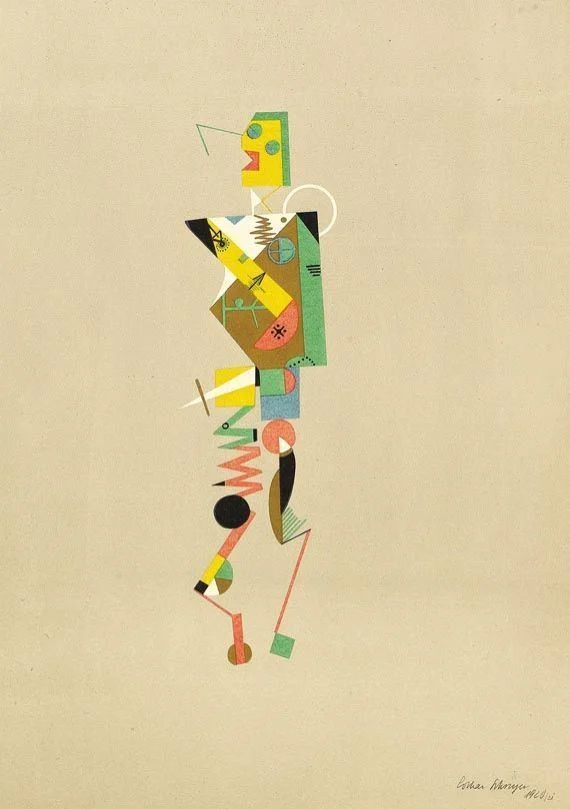

An evocative visual reaction to the birth of industrial advertising and ideals of beauty it furthered. In the work, a woman has not a head, but a lightbulb. A car tyre and a lever box her in on either side. BMW logos multiply behind her, while a hand holding a circular pocket watch emerges from behind a pouf of hair. Corporations and new technologies, apparently, have overtaken the subject’s individuality, while the clock suggests how time and labour were being monetized in new ways.

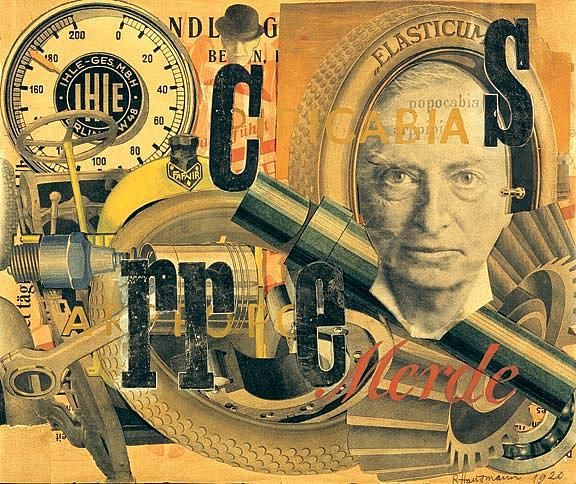

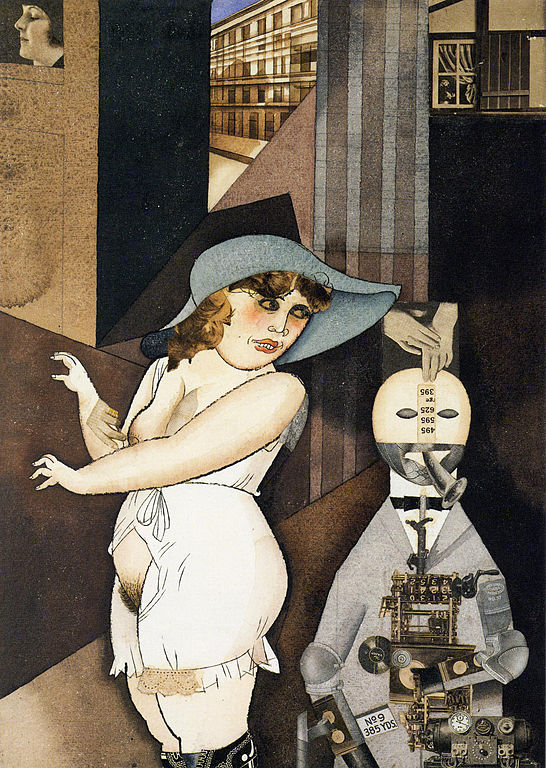

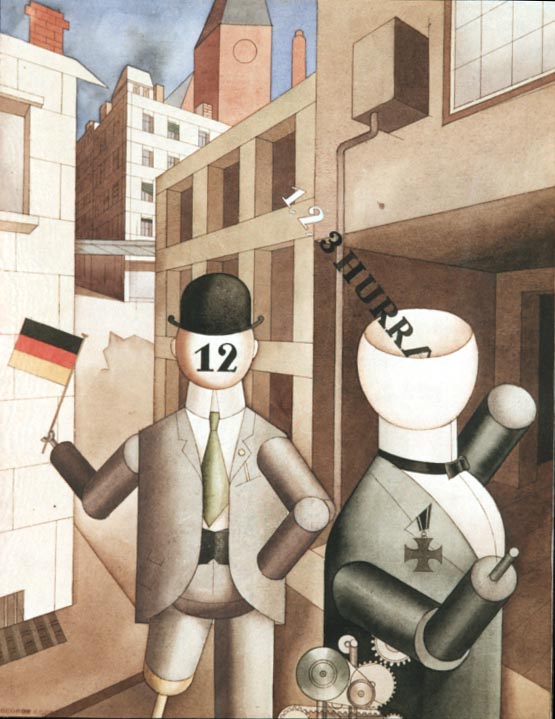

A multimedia sculpture constructed by George Grosz and John Heartfield. The work forces viewers to confront the reality of horrors inflicted by those involved in the First World War. The subject (the “Spiesser” or “Philistine,” represented here by a store-bought mannequin) is forcibly transformed by the world around him, as seen in the way that his body parts are replaced by fragments of the modern world such as the head by a light bulb and leg by a metal rod. In this work, Grosz and Heartfield indicated the way in which the world was changing those in it, forcing the audience to abandon their escapist art and reconcile with the transforming world in front of them.

ALSO: Rutherford postulates the hydrogen nucleus to be a new particle, which he dubs the proton. Rorschach devises the inkblot test. Max Wolf’s photos show the true structure of the Milky Way. The New York Times ridicules rocket scientist Robert H. Goddard, stating that spaceflight is impossible. First domestic radio sets come to stores in the United States. Red Army captures Odessa. The Hague selected as seat of International Court of Justice. The 19th Amendment gives women the vote; Harding elected US president. Hitler announces his 25-point program. Gandhi emerges as India’s leader in its struggle for independence. Sacco and Vanzetti arrested in Massachusetts. Wills Crofts’s The Cask (one of the first modern detective stories); Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise; Hasek’s The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk (1920–1923); Kafka’s “A Country Doctor”; Oppenheim’s The Great Impersonation; Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

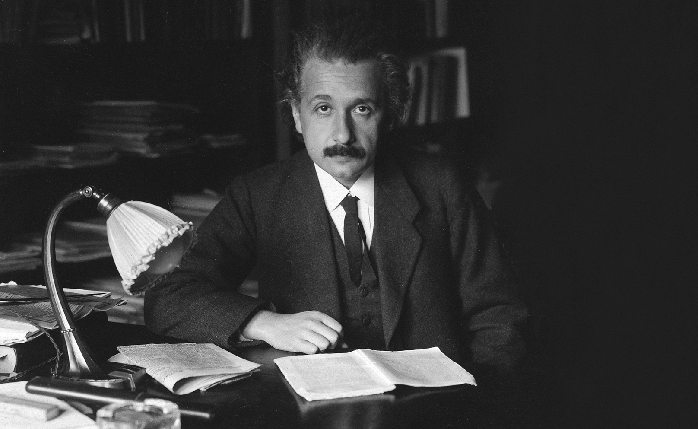

Einstein’s 1920 address “Ether and the Theory of Relativity” makes clear that his theory of relativity didn’t entirely do away with the “ether” that classical physicists had supposed to fill the spaces between particles and provide the medium for the transmissions of light. In fact, he says here, the general theory of relativity is, in effect, an ether theory: “The recognition of the fact that ’empty space’ in its physical relation is neither homogeneous nor isotropic… has, I think, finally disposed of the view that space is physically empty. But therewith the conception of the ether has gain acquired an intelligible content.”

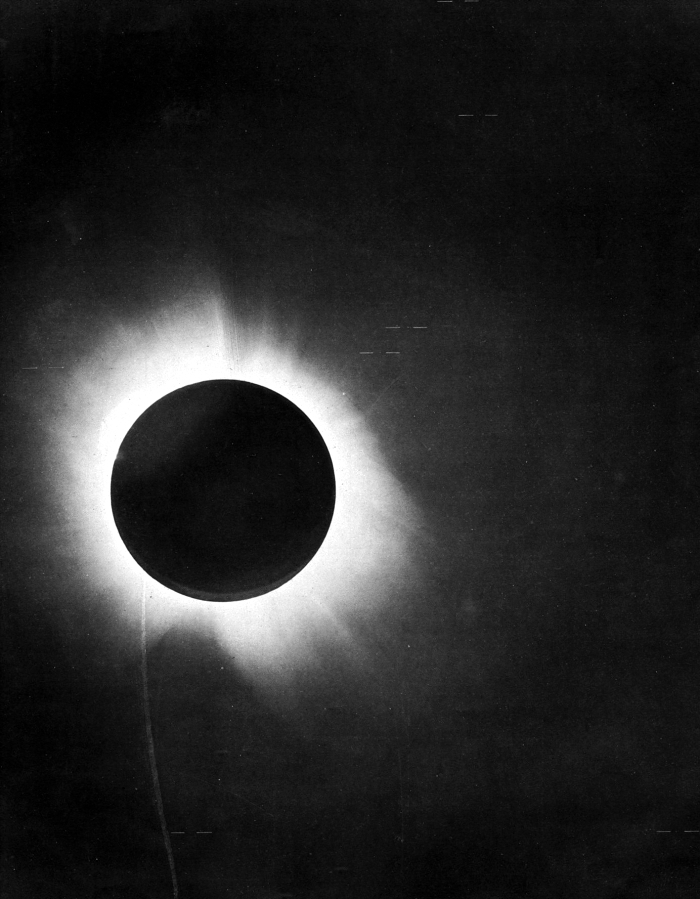

Arthur S. Eddington’s Space, Time, and Gravitation, which Rudy Rucker calls “excellent” in Geometry, Relativity, and the Fourth Dimension, gives a clear description of special relativity in terms of Minkowski’s diagrams. Eddington was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician (in 1919, he conducted an expedition to observe a solar eclipse that provided one of the earliest confirmations of general relativity; and around 1920, he foreshadowed the discovery and mechanism of nuclear fusion processes in stars); he was also a philosopher of science. The last chapter presents his striking idea that the illusions of permanent substance are built up out of “relations” which we mistake for laws.

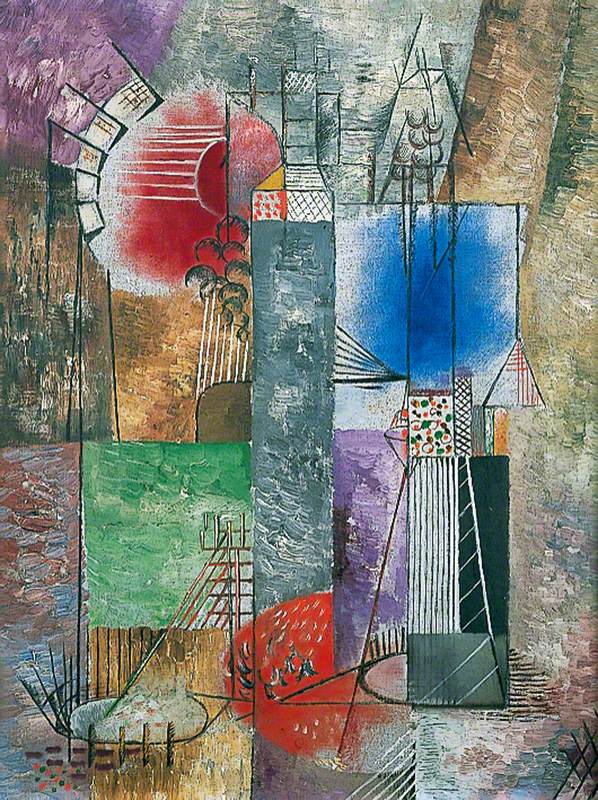

German-born architect and theorist Bruno Taut’s The Dissolution of Cities (1920). In such works as Alpine Architecture (1919), The City Crown (1919), The World-Master Builder (1919), and The Dissolution of Cities (1920), Taut developed a number of architectural visions that were not simply elaborations of a new architecture or new urbanism, but also schemata of a total spatial disposition to produce a utopian “new man.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin