RADIUM AGE: 1933

By:

December 3, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The year 1933, in my periodization scheme, marks the end of the cultural decade known as the “Twenties.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1933 (and 1934) as cusp years during which the Twenties end and the Thirties begin. In sf history, December 1933 is a key inflection point.

In 1933, Street and Smith purchased Astounding Stories and retooled its editorial policy. Street & Smith was a well-established pulp publisher, with an excellent distribution network; so the revived Astounding was quickly competitive. It was edited by F. Orlin Tremaine, with assistance from Desmond Hall. Tremaine was an experienced pulp editor, and Street & Smith gave him a budget better than the competing magazines could pay.

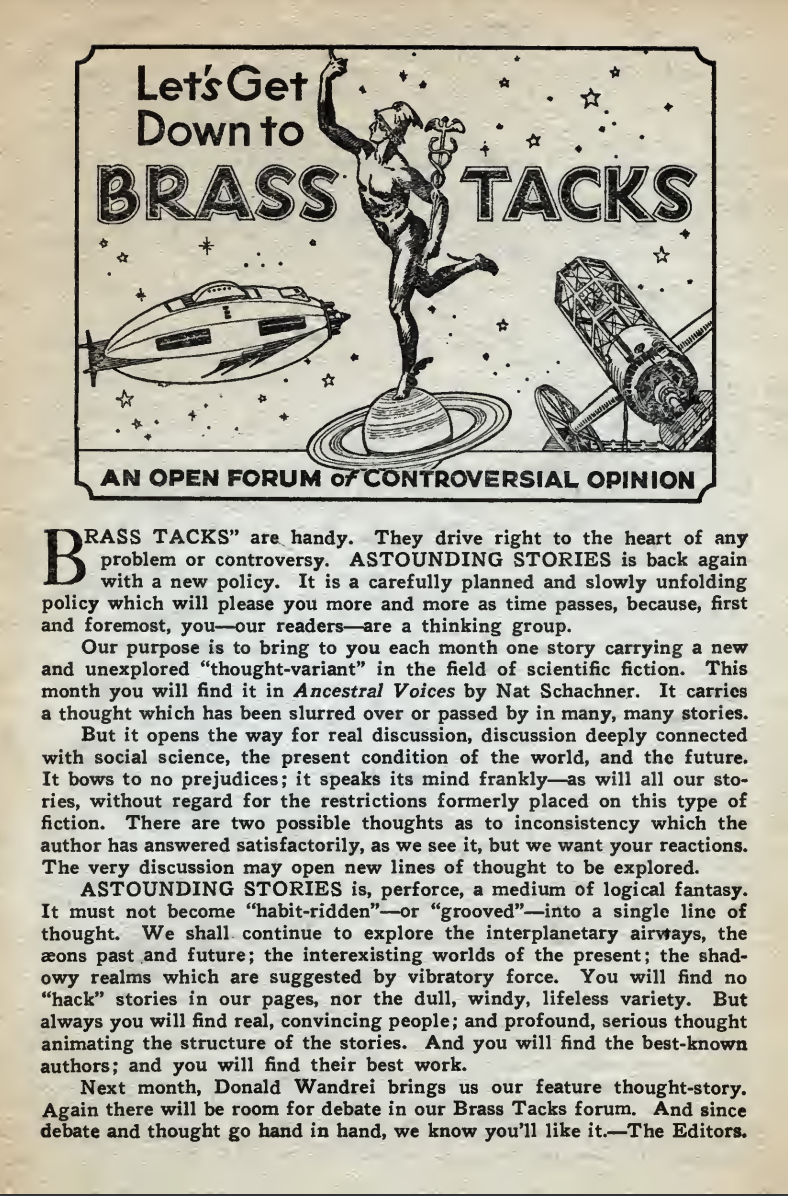

In December 1933 Tremaine wrote an editorial calling for “thought variant” stories that contained original ideas and did not simply reproduce adventure themes in a science-fiction context. The early stories identified by Tremaine as “thought variants” were not always particularly original, but it soon became apparent that Tremaine was willing to take risks by publishing stories that would have fallen foul of editorial taboos at other magazines.

Tremaine’s gambit paid off. By the end of 1934, Astounding was the leading SF magazine; important stories published that year include Murray Leinster’s “Sidewise in Time”, the first genre SF story to use the idea of alternate history; The Legion of Space, by Jack Williamson; and “Twilight”, by John W. Campbell, writing as Don A. Stuart. Within a year Astounding‘s circulation was estimated at 50,000, about twice that of the competition.

The Epilogue to Ashley’s Time Machines suggests that 1933 is phase 4 of a 25-year period of the pulp magazines (from inception to 1950). During this phase “cosmic sf” exploded — under Tremaine at Astounding — arguably the most exciting period in sf. This would encourage the return of space opera, which came back to dominance in the late 1930s and through the war. But it also led to the so-called Campbell revolution — i.e., taking a “rational” approach to technological progress.

Readers, beware of this rhetoric of rationality and maturity.

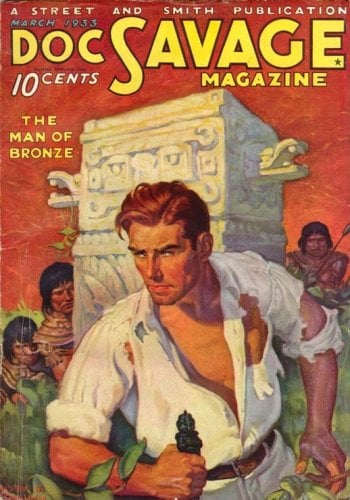

Hero pulps of 1933 include: Doc Savage (Mar. 1933-Summer 1949); The Phantom Detective (Feb. 1933-Summer 1953), and The Spider (Oct. 1933-Dec. 1943). Many of these pulps and other similar titles later converted into comic books.

Copyrighted works from 1933 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2029. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1933, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: EARTHSHIP | GYROBUS | ROBOTORIX | SPACEWAY | THOUGHT VARIANT (Astounding Stories editorial: “Our purpose is to bring to you each month one story carrying a new and unexplored ‘thought-variant’ in the field of scientific fiction.”) | TIME TRAVEL.

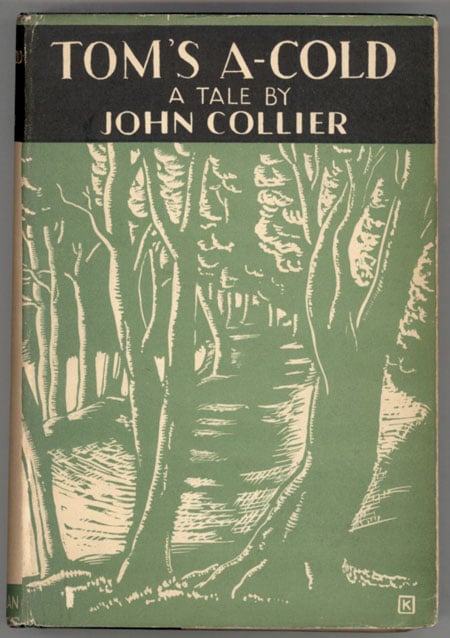

- John Collier’s Tom’s A-Cold (1933; US title: Full Circle). Though best remembered for his mordant, fantastical short stories, many of which appeared in The New Yorker, John Collier also wrote two Radium Age science fiction novels. Tom’s A-Cold is set in 1995, at which point England (along with the rest of the world, presumably) has reverted to a medieval-style social order and way of life. This is, in some sense, a “cozy catastrophe” — Collier describes the reborn natural world movingly. (What happened to civilization? Greed, laziness, and bureaucracy.) Harry, who has grown up in a valley in Hampshire, under the egotistic rule of the Chief, is being groomed by his grandfather, one of the few elders who remembers modern civilization, to take over the tribe. Over the course of a summer and fall, during and after a raid on a nearby village, to capture women, Harry does become Chief — but at the cost of everything he cares about. Fun fact: Collier was a fixture on the English literary scene during the 1920s and ’30s. In Hollywood, years later, he helped develop TV shows like Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

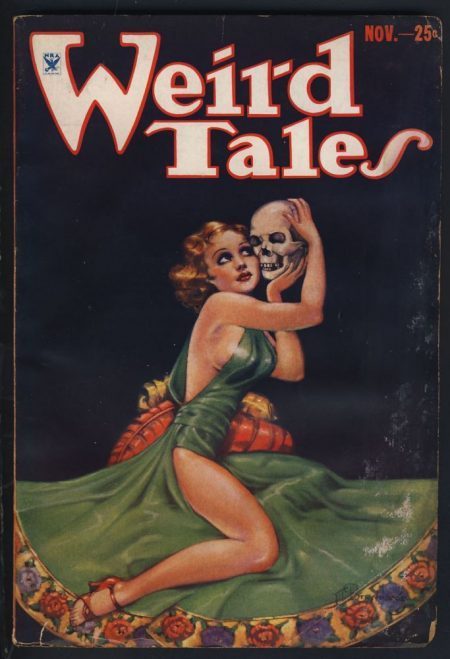

- C.L. Moore’s Northwest Smith (1933-on; collected in book form, 1953). In the far future, humankind has colonized the solar system. The ruthless, cynical spaceship pilot and smuggler Northwest Smith roams from planet to planet, looking to make a quick buck. In “Shambleau” (November 1933), for example, Smith rescues a strange, beautiful girl from a Martian mob; in “Black Thirst” (April 1934), he ventures into a forbidden Venusian fortress. And in “Dust of Gods” (August 1934), Smith and his Venusian comrade, Yarol, take a job searching for the physical remnants of a dead god. In many of these yarns, all of which appeared in Weird Tales — during that magazine’s H.P. Lovecraft/Robert E. Howard/Clark Ashton Smith era — Smith undergoes outré psychological/spiritual trials, which take place in extra-dimensional or dream-like contexts. Fun fact: Catherine Lucille Moore was among the first women to write pulp science fiction and fantasy. She and her first husband, Henry Kuttner, were prolific co-authors.

- Raif Necdet’s Semavi İhtiras (The Celestial Passion). One of the earliest Turkish sf utopias, written by a Turkish nationalist author. A future secular and republican Turkish utopia is imagined. The story is about Nobel Prize winning Turkish authors and Turkish women who have many more freedoms — including freedom of mobility — than they did at the time. I heard about this from a presentation by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad, founder and editor of the Islam and Science Fiction Project. He teaches Computer Science at the U. Washington.

- Sadeq Hedayat’s “Seen Ghaff Laam Laam” (س گ ل ل) or “S.G.L.L.” Sadeq Hedayat is considered to be one of the foremost short story writers of the Farsi language of the modern era. The story deals with what looks like the impending demographic disaster of the 20th century i.e., overpopulation. With the invention of a sterility serum it seems that the problem can be avoided — but the serum creates other problems, including uncontrollable lust, depression, and suicide. Catastrophe results. Iraj Bashiri has described “S.G.L.L” like so: “The serum of sterility, which was supposed to lead the way to zero population growth, turned into a serum of lust producing a nightmare in which arson, manslaughter, and suicide prevailed.”

- Lester Dent’s Doc Savage (1933-on). In a perfect example of the first-time-as-comedy-second-time-as-tragedy trope, the “Doc Savage” character — Clark Savage Jr., a nearly superhuman surgeon, scientist, adventurer, inventor, explorer, and researcher — is an earnest version of Henry Stone, protagonist of Philip Wylie’s sardonic superman novel The Savage Gentleman (1932). An expert at disguise, not to mention hand-to-hand combat, Savage’s only goal in life is to right wrongs and punish evildoers. He is accompanied, in many of his adventures, by the brilliant chemist “Monk” Mayfair, dapper attorney (and Brigadier General) “Ham” Brooks, construction engineer and strongman “Renny” Renwick, electrical engineer “Long Tom” Roberts, and be-monocled archaeologist Johnny Littlejohn. Their HQ is on the 86th floor of a New York skyscraper (implicitly the Empire State Building); and Savage also has a Fortress of Solitude in the Arctic. Here we see Golden Age themes and memes emerging from the Radium Age. Fun fact: Of the 181 Doc Savage novels published by Street and Smith, 179 were credited to Kenneth Robeson; all but twenty of these novels were written by Lester Dent. Doc Savage became known to more contemporary readers when Bantam Books began reprinting the novels in 1964.

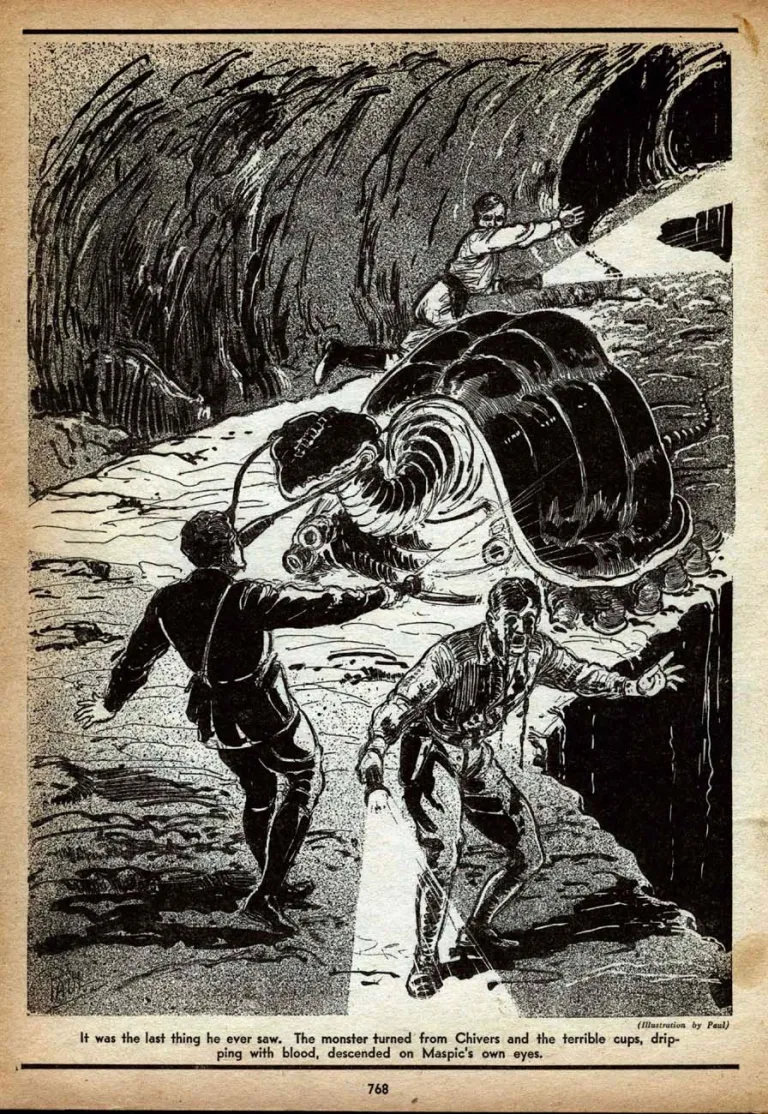

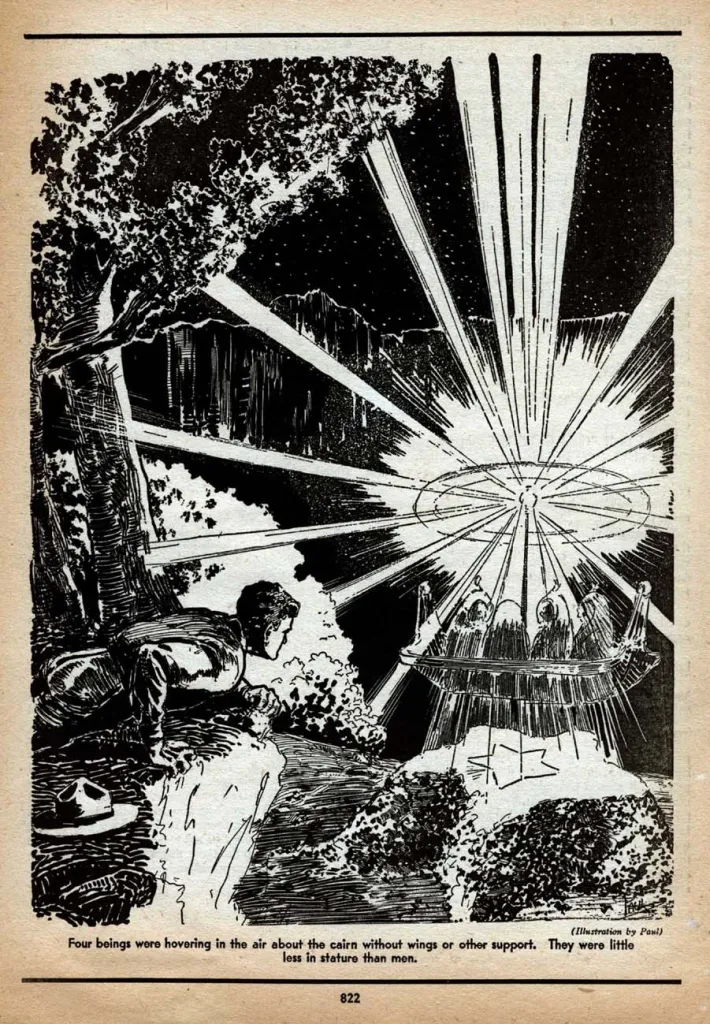

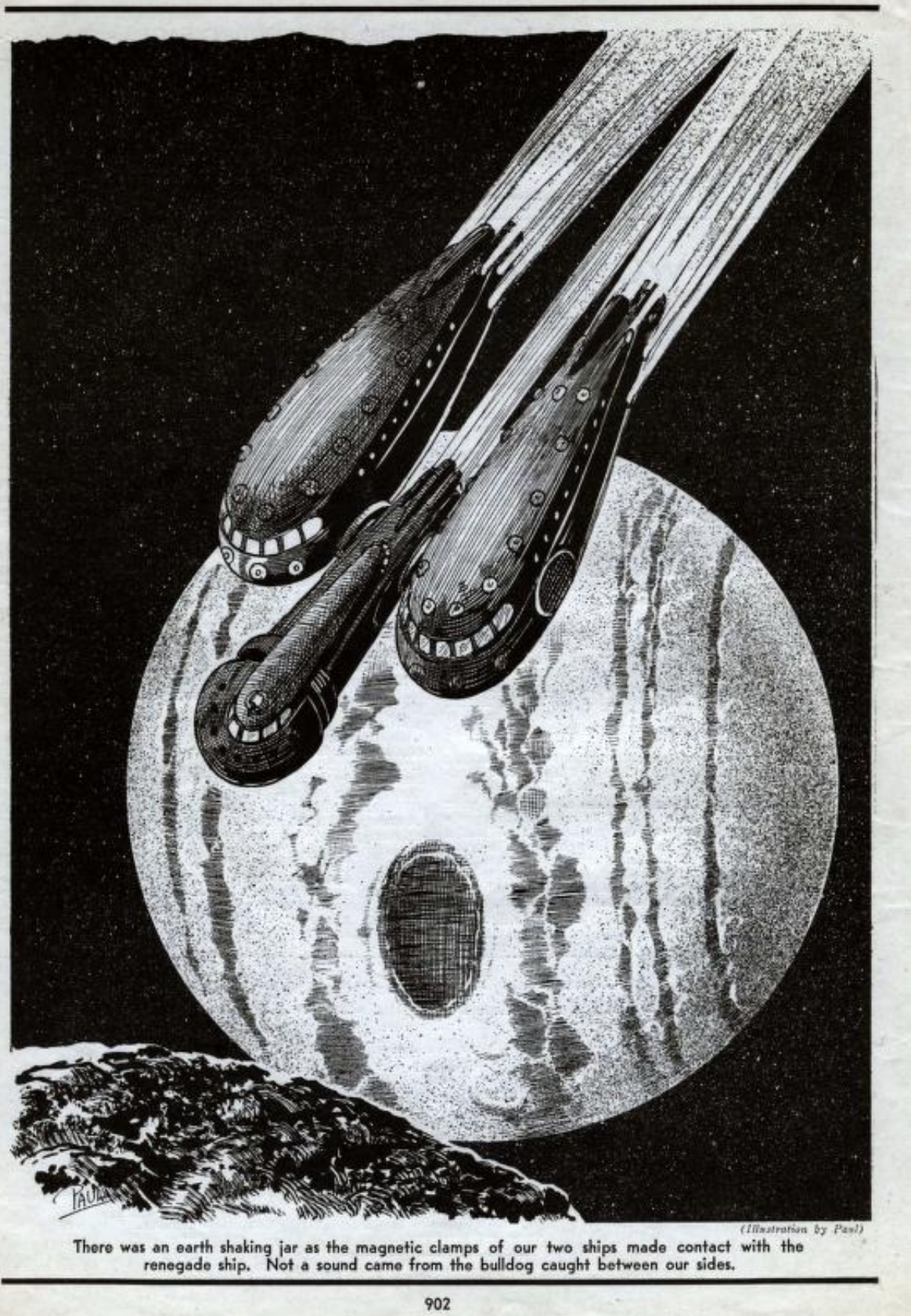

- John Wyndham (John Beynon Harris)’s Exiles on Asperus. Novelette – Wonder Stories Quarterly Winter 1933, illustrated by Frank R. Paul. Moskowitz calls it avant garde, though the SFE says none of Harris’s pre-WWII stands out in particular.

- John Wyndham (John Beynon Harris)’s “Wanderers of Time” (Wonder Stories, March 1933). Mentioned by Moskowitz as the best of the author’s early time travel stories.

- Lao She’s Maocheng Ji [“A Record of the City of Cats”] (1933; rev 1947; trans James Dew as City of Cats 1964; trans W A Lyell as Cat Country 1970). Remains one of the most significant Chinese sf novels. This dystopia about the catlike residents of Mars disguises a satire of the Old China and reactionary rule. The civilization has long passed its glorious peak and has undergone prolonged stagnation. The visitor observes the various responses of its citizens to the innovations by other cultures. Lao She wrote the book in response to Japan’s invasion of China (Manchuria in 1931, and Shanghai in 1932). Fun fact: Lao She supposedly wrote without any knowledge of the sf genre, although it is likely he at least glimpsed it during his five-year posting to London as a lecturer in Chinese.

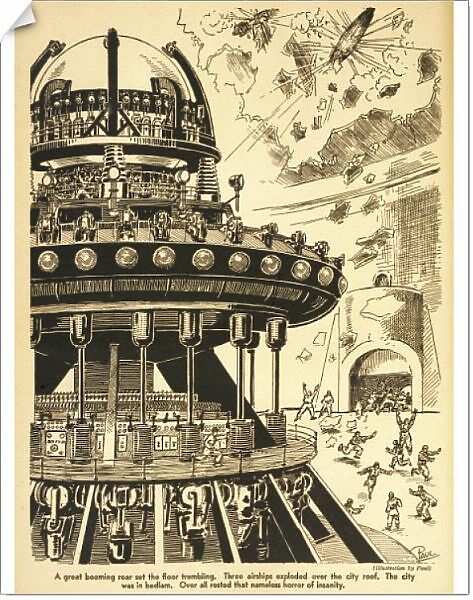

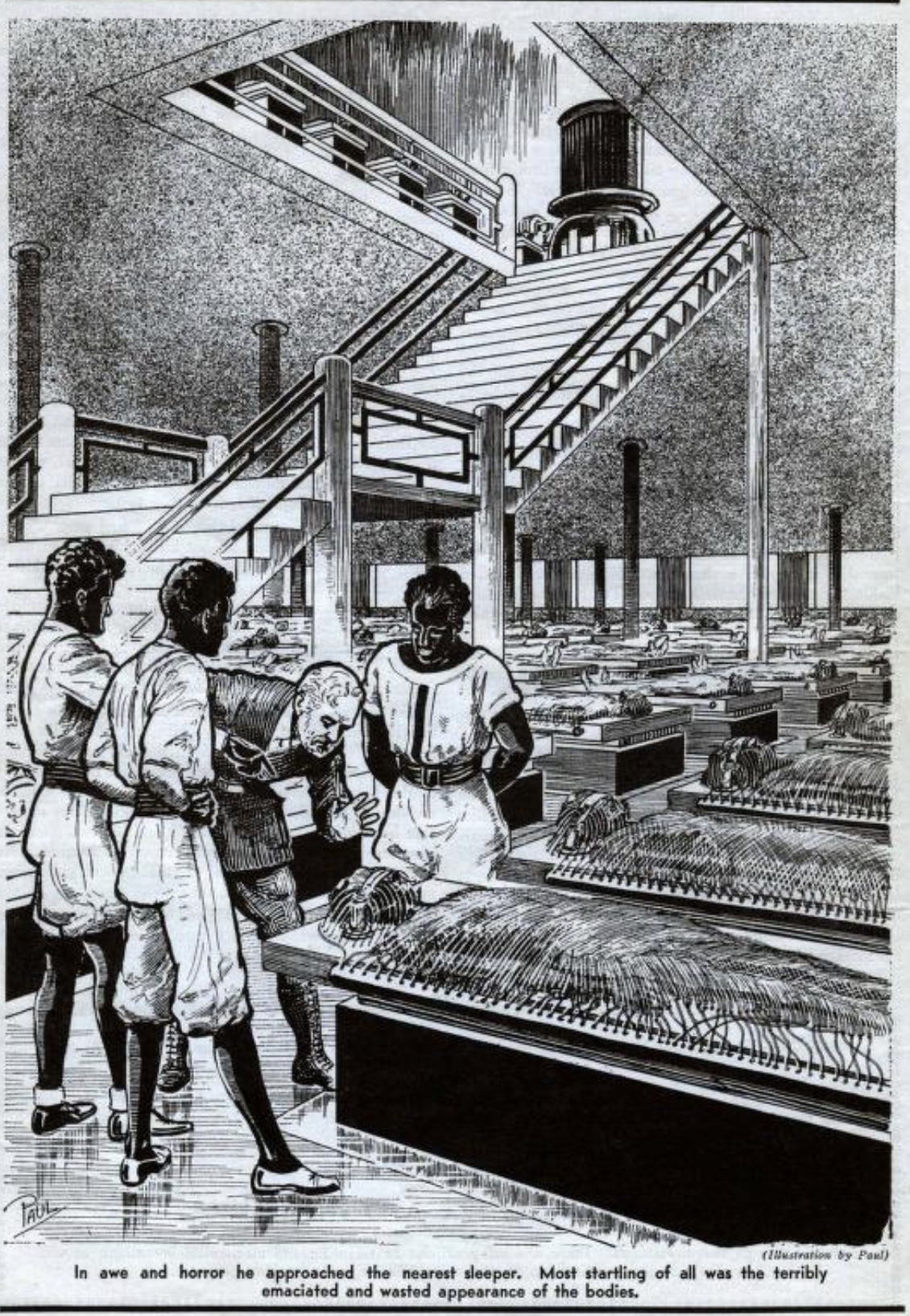

- Laurence Manning’s The Man Who Awoke (serialized 1933 in Wonder Stories; as a book, 1975). Having developed a lead-lined chamber which prevents aging, a means of putting himself into a coma at will, and a wake-up ray, scientist Norman Winters puts himself into suspended animation — intending to emerge in a utopian future, three thousand years hence. Instead, he wakes up five thousand years later, in a WALL-E-esque dystopia; the world has been reduced to a garbage heap after the “Age of Waste.” Winters proceeds to travel ahead in time several more times, and encounters: strong artificial intelligence (a super-computer, The Brain, supervises and manages all humankind), Matrix-like virtual reality (the sleeping outnumber the awake), desktop molecular manufacturing (a world of plenty, in which each individual is his or her own city-state), immortality (humankind scatters to the far reaches of the cosmos, out of boredom). Olaf Stapledon’s far-out future vision plus Hugo Gernsback’s ability to predict future tech equals… a proto-Iain M. Banks, perhaps. Though the writing leaves something to be desired. Fun fact: Includes a remarkably advanced passage about ecology and the rationing of fossil fuels. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- A.E.’s The Avatars: A Futurist Fantasy. George William Russell (1867 – 1935), who wrote with the pseudonym Æ (often written AE or A.E.), was an Irish writer, editor, critic, poet, painter and Irish nationalist. In 1886 he and William Butler Yeats helped found the Dublin Lodge of the Theosophical Society and much of his work reflects a mystical agenda; this novel, one of only two that he wrote, is dedicated to Yeats. In The Avatars, AE presents his own picture of what might happen if the socialistic state assumed control. So efficient has it become, that no one is homeless or insecure. Yet, there is something in man that rebels against it. “The spirit of man has lost itself in many illusions, and last of all it may lose itself in the most pitiful of any, the illusion of economic security and bodily comfort. These now fail to satisfy it, and there is nothing for it but spiritual adventures. Poet, artist, visionary, all are there.” Set in a future Ireland, two supernal beings hauntingly invoke a vision of a world less abandoned to materialism, their seductive discourse drawing the protagonists to “the margin of the Great Deep”, as Monk Gibbon puts it in his long and informative essay on AE’s work which introduces The Living Torch (collection 1937), a posthumous volume of nonfiction. Also see AE’s proto-sf novel The Interpreters (1922).

- Charles R. Tanner’s “Tumithak in Shawn” (Amazing). Survivors of an alien invasion of earth; sequel to a 1932 story. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

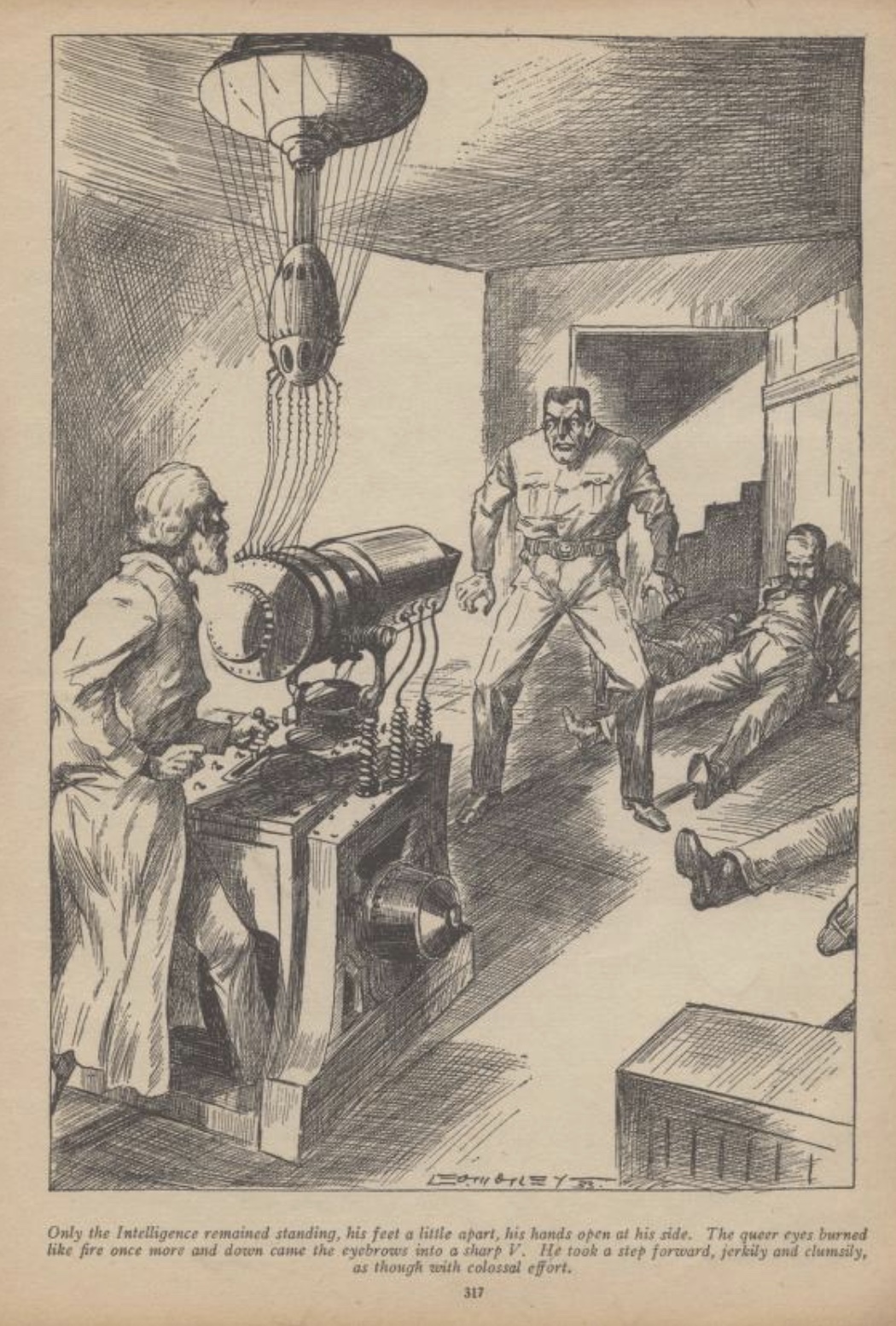

- John Russell Fearn’s “The Intelligence Gigantic” Amazing June-July 1933). Fearn’s first story — a superman story. A parable attacking the amorality of hyper-rational and unemotional superhuman. UK author; extremely prolific, he used many pseudonyms. During the 1930s he wrote for magazines, including the US pulps, but during World War Two he would switch to books. He became a central figure in the postwar paperback boom, writing numerous Westerns, crime stories and romances as well as his sf, most of which appeared under the excellent names “Vargo Statten” and “Volsted Gridban.”

- Margaret Maud Brash’s Unborn Tomorrow. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- P. Schuyler Miller’s “The Forgotten Man of Space” (Wonder Stories). Ashley’s Time Machines calls it one of the best stories of the year — a fine example of self-sacrifice by a space explorer determined to protect the innocent inhabitants of Mars.

- Frank K. Kelly’s “The Moon Tragedy” (Wonder Stories). Kelly was a teenager, one of the best proponents of the new hard realism; this one is about the fate of the last explorers to the Moon.

- Neil R. Jones’s Professor Jameson story “Into the Hydrosphere.” Ashley’s Time Machines says this is when the Professor Jameson stories started to come alive.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Dweller in the Gulf” (Wonder Stories, March 1933).

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Light From Beyond” (Wonder Stories, April 1933).

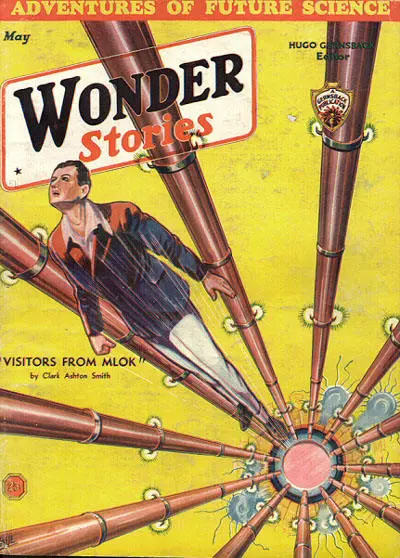

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Visitor From Mlok” (aka “A Star-Change”) (Wonder Stories, May 1933).

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Demon of the Flower” (Astounding Stories, December 1933).

- March Cost (Margaret Mackie Morrison)’s A Man Named Luke. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

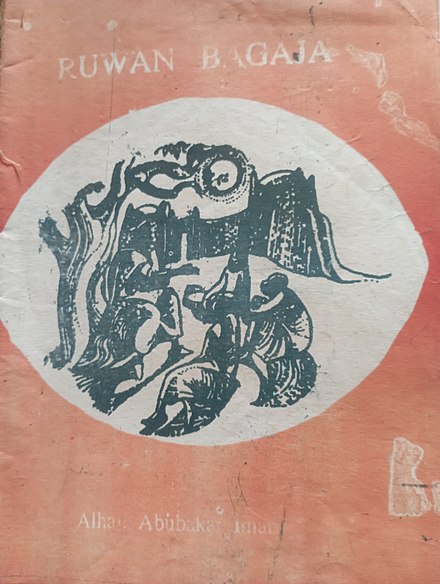

- Alhaji Abubakar Imam’s [also: Abubakar Iman] Ruwan Bagaja (The Water of Cure). I’ve seen it described as sf, but seems like it is somewhere in between popular Arab epic (sira), fairy tale and a picaresque novella (makama). Begins with a quest story of a diseased prince who sets out on an adventure to find the Water of Cure. He travels through many places, kingdoms, deserts and sees many wonders of Earth. Informed that no human has ever been able to reach it for centuries — and that the reality of the Wter of Cure has slowly faded away into a myth, — our protagonists insists that if the water of cure did indeed exist, then he sees no reason to give up searching for it. Abubakar Imam (1911 – 1981) was a Nigerian writer, journalist and politician from Kagara, Niger in Nigeria. Thanks to the acclaim from Ruwan Bagaja, he would go on to publish nearly 20 other Hausa books including the celebrated three-volume collection of stories Magana Jari Ce. For most of his life, he lived in Zaria, where he was the first Hausa editor of Gaskiya Ta Fi Kwabo, the pioneer Hausa-language newspaper in Northern Nigeria. Fun fact: A school-reader translation into English was published in 1971. —

- Arthur Frederick Jones’s “The Inquisition of 6061” — parable on a future dystopia, featuring thought control.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Vibrometer.” Not usually anthologized. It appeared in a mimeographed pamphlet called Science Fiction. The editors, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who would go on to create the Superman comic, were high school students in Cleveland at the time.

- Edmond Hamilton’s The Man with the X-Ray Eyes.

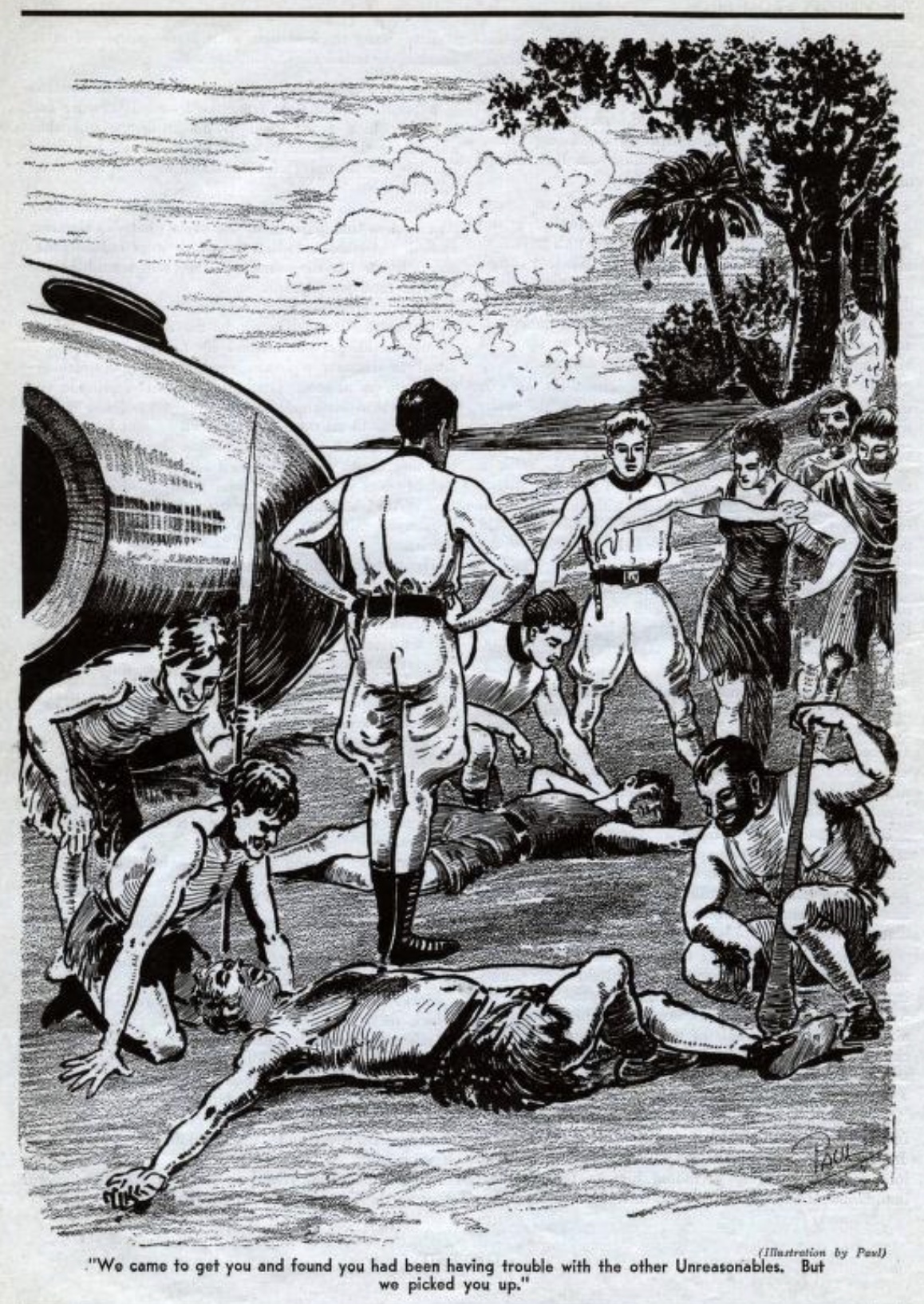

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Island of Unreason.” He was very popular as an author of space opera, a subgenre he created along with E.E. “Doc” Smith. His story “The Island of Unreason” (Wonder Stories, May 1933) won the first Jules Verne Prize as the best science fiction story of the year (this was the first science fiction prize awarded by the votes of fans, a precursor of the later Hugo Awards).

- Edmond Hamilton’s “War of the Sexes.” Mentioned in the Moskowitz collection When Women Rule. A 20th century man finds himself in a women-ruled future. Is it all a dream?

- Evelyn Waugh’s “Out of Depth: An Experiment begun in Shaftesbury Avenue and Ended in Time” Only a few examples of Waugh’s fiction make genuine use of sf displacements. The American protagonist (Rip Van Winkle, a lapsed Catholic) of “Out of Depth” (December 1933 Harper’s Bazaar) undergoes time travel via a combination of magical wish-granting — there’s a fraudulent magician not unlike Alastair Crowley — and a car crash to ruined London five centuries hence. It’s inhabited by white “savages” – an “unlettered race” depending on oral tradition – with civilization represented by black African colonists including, characteristically, a Catholic mission. Rip has his head measured by calipers, etc.

- Geoffrey Dearmer’s Saint on Holiday. Presents a near-future UK in which the government is dominated by ministries designed to be of benefit to citizens; it was couched as a topsy-turvydom satire.

- George Schuyler’s “Golden Gods: A Story of Love, Intrigue and Adventure in African Jungles (December 1933-February 1934 Pittsburgh Courier) as by Samuel I Brooks. It’s a Lost Race tale.

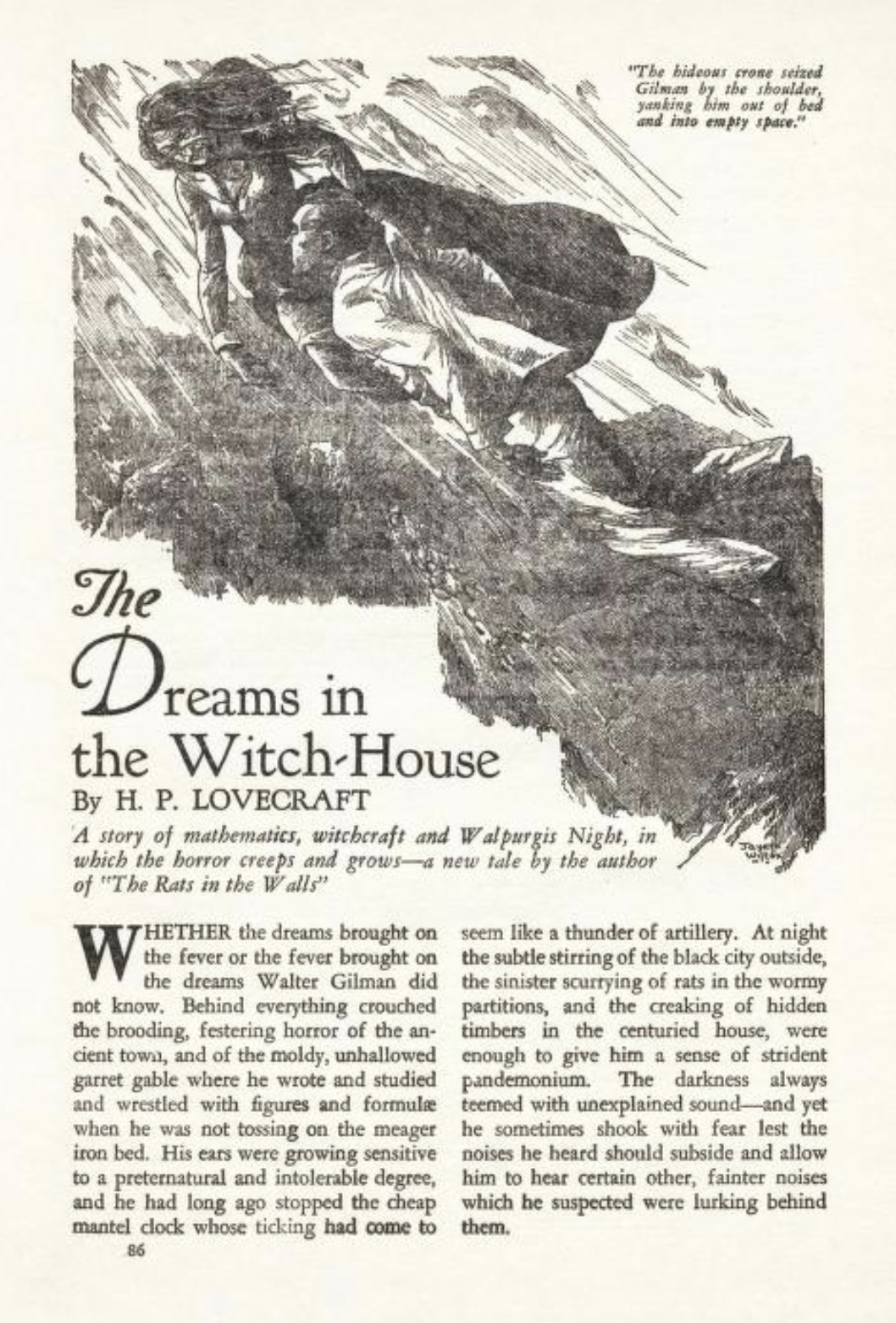

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Dreams in the Witch-House.” It was written in January/February 1932 and first published in the July 1933 issue of Weird Tales. Walter Gilman, who came to Miskatonic University to study “non-Euclidean calculus and quantum physics”, which he linked to the “fantastic legends of elder magic”, rents an attic room in the Witch House, a house in Arkham, Massachusetts, that is rumored to be cursed. The house once harbored Keziah Mason, an accused witch who disappeared mysteriously from a Salem jail in 1692. Gilman discovers that, for the better part of two centuries, many of the attic’s occupants have died prematurely. The dimensions of Gilman’s attic room are unusual and seem to conform to a kind of unearthly geometry. Gilman theorizes that the structure can enable travel from one plane or dimension to another. Gilman begins experiencing bizarre dreams in which he seems to float without physical form through an otherworldly space of unearthly geometry and indescribable colors and sounds. Among the elements, both organic and inorganic, he perceives shapes that he innately recognizes as entities that appear and disappear instantaneously and at random. Several times, his dreaming self encounters bizarre clusters of “iridescent, prolately spheroidal bubbles”, as well as a rapidly changing polyhedral figure, both of which appear sapient! Fun facts: “The Dreams in the Witch House” was likely inspired by Willem de Sitter’s lecture The Size of the Universe, which Lovecraft attended three months prior to writing the story. De Sitter is mentioned by name in the story, described as a mathematical genius, and listed in a group of other intellectual masterminds, including Albert Einstein. Several prominent motifs — including the geometry and curvature of space and using pure mathematics to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of the universe — are covered in both Lovecraft’s story and de Sitter’s lecture. The idea of using higher dimensions of non-Euclidean space as short cuts through normal space can be traced to A.S. Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World which Lovecraft alludes to having read. These new ideas supported and further developed the concept of a fragmented mirror space, previously introduced by Lovecraft in “The Trap” (1931).

- J. Leslie Mitchell’s Persian Dawns, Egyptian Nights (two linked story sequences) with a foreword by J.D Beresford. Includes an Apes as Human tale, “The Last Ogre” (June 1932 Cornhill Magazine). Mitchell (1901-1935) was a Scottish journalist and author. His Hanno; Or, the Future of Exploration (1928 chap) – part of the To-day and To-morrow series — gave us some humorous but basically Wellsian thoughts about exploring both space and the centre of the Earth.

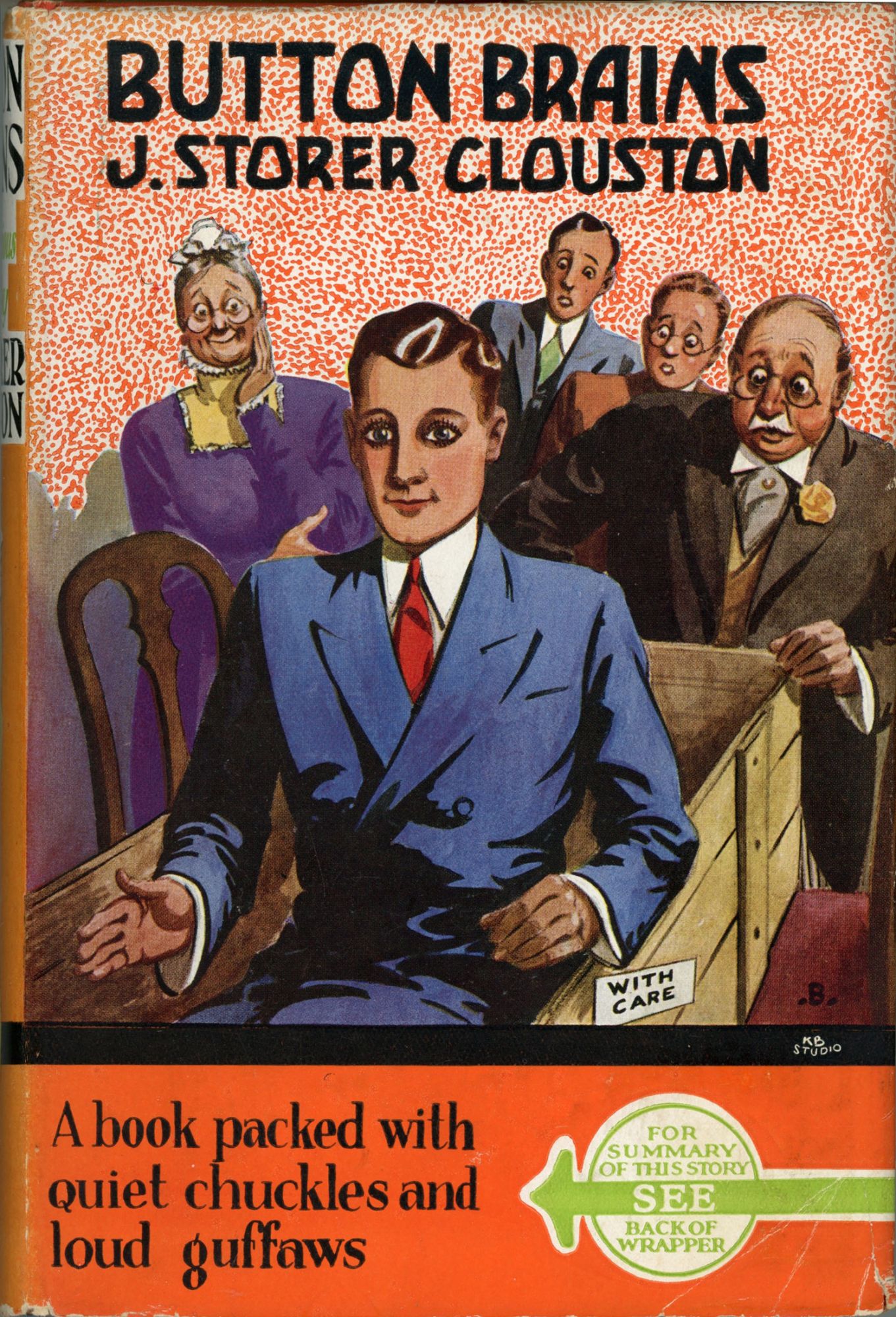

- J. Storer Clouston’s Button Brains. About a mechanical robot (not an android) that is taken for the human upon which it was modeled. Turns on the human’s pretending to be a robot, with comic consequences.

- Harry Stephen Keeler’s The Face of the Man from Saturn (Amazing Stories for April 1927, also titled The Crilly Court Mystery) is not itself sf but centers on a piece of sf artwork concealing another hidden message, and includes the inset sf story “John Jones’s Dollar” (by Keeler, August 1915 Black Cat), here introduced as a manuscript titled “How Socialism Finally Arrived in the World!” — socialism being one of Keeler’s enthusiasms. The “John Jones’s Dollar” framing story predicts online education via teleconference, as a professor in 3221 CE (3235 in The Face of the Man from Saturn) addresses his globally scattered class.

- John Gloag’s The New Pleasure. Ironic utopia — a gentle satire in which people realize that modern civilization stinks.

- Leo Perutz’s St Petri-Schnee (trans E B G Stamper and F M Hodson as The Virgin’s Brand 1934; new trans Eric Mosbacher as Saint Peter’s Snow 1990). Written by an Austrian Jew; depends upon a sense that human civilization is a fragile contrivance. The title refers to a drug which induces religious fervor; the Nazis, understandably, did not care for it — it was suppressed in Germany. The eponymous hallucinogenic drug derived from an ergot fungus (this was 10 years before the discovery of LSD) at the center of this tale has been, from time immemorial, responsible for periodically spreading a virus which induces faith in humans. In 1932, after long dormancy, the virus has been deliberately re-injected into European wheat strains in order to revitalize Christianity, but the religious impulse in humans turns always to what feeds the addiction, and the deity waiting to be invoked by this pandemic turns out not to be God but Moloch. The book has been called “a psychological detective story”, as well as science fiction. un facts: Perutz was a mathematician who formulated an algebraic equation which is named after him. He escaped to Palestine (via Venice) in 1938. Austrian fellow novelist Friedrich Torberg once characterized Perutz’s literary style as the possible result of a little infidelity of Franz Kafka and Agatha Christie.

- Leslie F. Stone’s “Gulliver, 3000 AD” (Wonder Stories, May 1933).

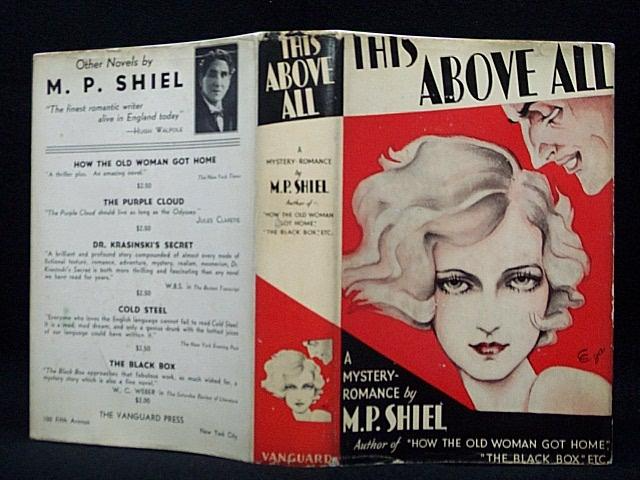

- M.P. Shiel’s This Above All. Describes the contemporary adventures of a trio of immortals made so by Jesus Christ, who is alive in Tibet.

- Michael Arlen’s Man’s Mortality. A Pax Aeronautica tale bearing elements in common with Kipling’s With the Night Mail (see 1905). Vividly depicts the collapse of International Aircraft and Airways in 1987, after 50 years of oligarchy, through the invention of a power source that enables disaffected citizens to outmanoeuver the government. The melodramatic story carries some moral bite, and was clearly written after the Pax Aeronautica had lost plausibility as a doctrine or wish. There is an antichrist-like rebel. Fun fact: (UK-Bulgarian-Armenian author, 1895-1956, born Dikran Kouyoumdjian, in the UK from 1901.

- Nat Schachner’s “The Robot Technocrat.” Schachner (1895-1955) was a US chemist, lawyer and author.

- Nat Schachner’s “Ancestral Voices” (December 1933 Astounding). This was the first so-called Thought-Variant story to feature in the magazine. Satirizes notions of racial purity.

- Neil Bell’s apocalyptic black comedy The Lord of Life, a parody of M.P. Shiel’s recently reprinted Lord of the Sea (1901) and The Purple Cloud (1901). Nineteen men and one woman, safely under the sea, survive the ed of the world which has been caused by a mad scientist, but then must work out an Adam and Eve protocol for preserving the race!

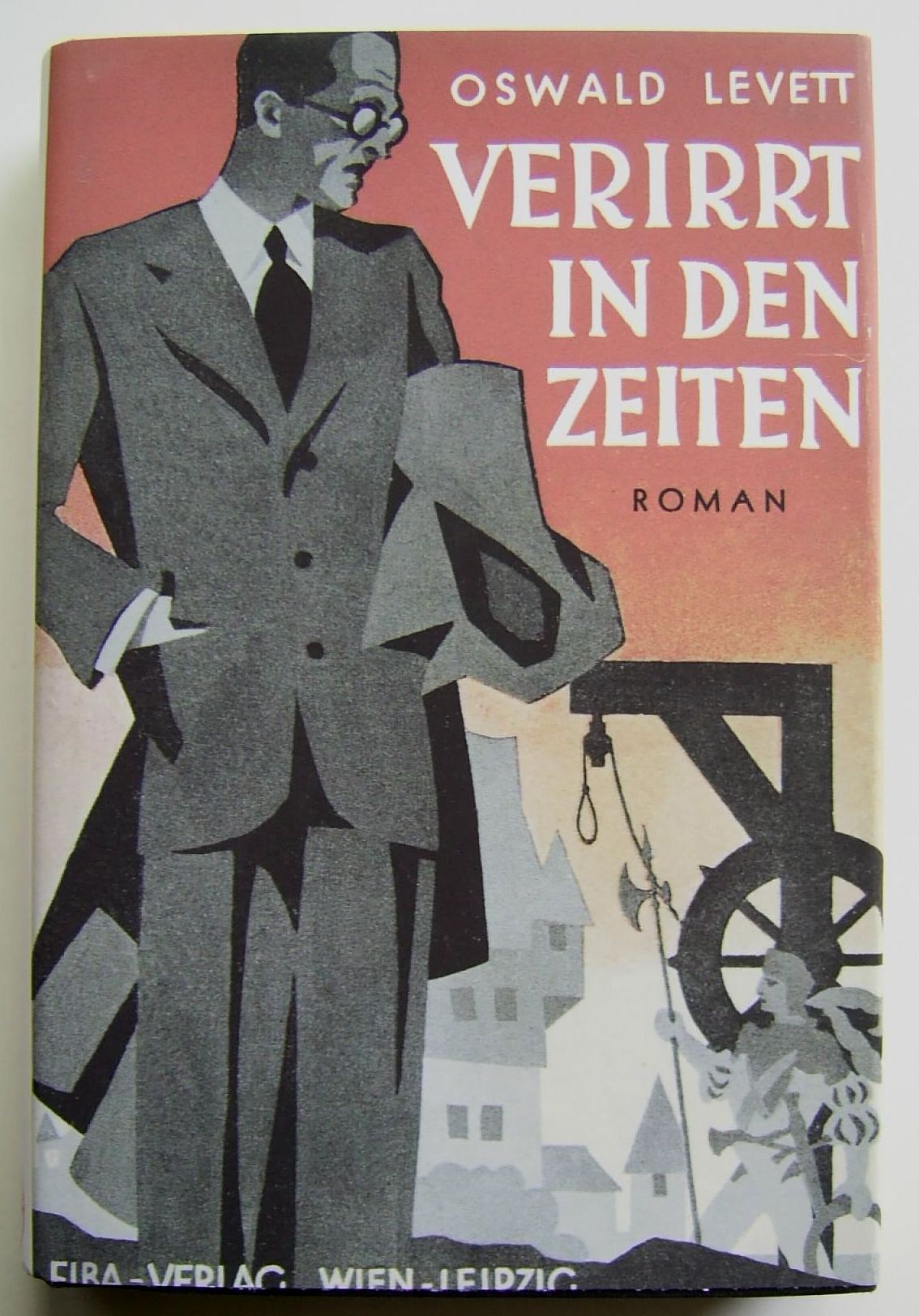

- Oswald Levett’s Verirrt in den Zeiten [“Lost in Time”]. Levett (1884-1942), was a Viennese Jewish lawyer who died en route to the Nazi extermination camp at Maly Trostenets (near Minsk) in October 1942. This is a time-travel novel of a journey back to the Thirty Years’ War and an unsuccessful attempt to change history.

- Helen Simpson’s The Woman on the Beast. Three linked stories, the last, “Australia, 1999,” set in the future. Mrs. Sopwith (a thinly disguised Aimee Semple Macpherson), the Antichrist, becomes world ruler. Books burnt, privacy abolished, thought control, end of the world.

- W H Auden’s The Dance of Death is supposed to be of sf interest. A satiric musical extravaganza that portrays the “death inside” the middle classes as a silent dancer. The dancer first attempts to keep himself alive through escapism at a resort hotel, then through nationalistic enthusiasm, then through idealism, then through a New Year’s party at a brothel, before he finally dies. Karl Marx appears on stage and pronounces the dancer dead. “The instruments of production have been too much for him.” Plays with different styles by quoting popular and music-hall songs, parodying Lawrence and alluding to Brecht. It was widely interpreted as pro-Communist, but Auden later wrote in a copy of the printed text, “The communists never spotted that this was a nihilistic leg-pull.”

- Maurice Renard’s final sf novel, Le Maître de la lumière (The Master of Light), serialized in 1933. Somewhat similar to his earlier novel Le Singe, it is an odd and eclectic mixture of soap-opera romance, family vendettas, detective-cum-Gothic horror, and adventure, with just enough scientific speculation to be classified (marginally) as sf. The plot takes place in 1929-30 and revolves around the murder, a century earlier, of a Napoleonic navy officer during the unsettled times immediately following the July Revolution. Charles Christiani, his descendant and the young hero of the story, eventually comes to discover the identity of the true murderer of his great grandfather with the aid of a special plate of glass that had originally hung in the window of the deceased’s home. This mica-like glass, brought back by his ancestor from the jungles of an uncharted Indonesian island, possesses the unusual property of reflecting the images of events occurring long before.

ALSO: Anderson and Millikan discover positrons; Farnsworth develops electronic television. Adolf Hitler appointed Chancellor of Germany; Reichstag fire in Berlin; Goebbels named Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda; Hitler granted dictatorial powers; the first Nazi concentration camps; boycott of Jews in Germany begins; all books by non-Nazi and Jewish authors burned; modernist art in Germany suppressed. Jung’s Modern Man in Search of a Soul; Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London; Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. James Hilton’s Lost Horizon; Roy Crane’s Captain Easy comic strip (1933–1937), Dashiell Hammett‘s The Thin Man (serialized, 1933; in book form, 1934), Guy Endore’s The Werewolf of Paris. Ulysses allowed into the US after court ruling. James Whale directs the film version of The Invisible Man; Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse; King Kong. Sixty thousands artists and authors leave Germany, including Kandinsky and Klee. Death of Annie Besant. Chicago World’s Fair. “Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf” a popular song in the US.

Yeats’ The Winding Stair (1933). In The Present Age After 1920:

Winding stairs, spinning tops, ‘gyres’, spirals of all kind, are important symbols in Yeats’s later poetry, not only are they connected with his philosophy of history and personality, they also serve as a means of resolving some of those dichotomies that had arrested hum from the beginning. Life is a journey up a spiral staircase; as we grow older we cover the

ground we have covered before, only hiher up, as we look down the winding stairs below us we see the places where we were but no longer are, measuring our progress by the increased number of our absences. The journey 1s both repetitious and progressive, we both travel in a circle and go forward. To resolve the ‘antinomies’ of life we must be able to be on all parts of the circle’s circumference at once. The circles get smaller as the winding stair spirals to its summit, at

the top, where the circle diminishes to a point, we will be standing on a circle whose circumference 15 infinitely small, and thus be everywhere on it at the same time. But the tower is ruined at the top, and when we arrive at the summit we reach old age and death. The dance of life includes death. Outside time the antinomies are resolved.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin