RADIUM AGE: 1906

By:

May 28, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

In 1906, Munsey added The Scrap-Book (Mar. 1906-Jan. 1912) to The Argosy and All-Story; Street & Smith created The People’s Magazine as a companion to The Popular. In October, Munsey issued The Railroad Man’s Magazine — the first specialist pulp magazine.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1906.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1906, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ANTIGRAVITY (F. L. Keates “Man in the Air” in Scrap Book).

- Van Tassel Sutphen’s The Doomsman. Set ninety years after the cataclysmic Terror of 1925, Sutphen’s book imagines that the world of 2015 has devolved into three tribes: the Painted People, the House People, and the marauding Doomsmen. Keeps, drawbridges, archery, and Sirs and Ladies have grown back as thickly as vines over the ruins of American civilization. It has been suggested that Sutphen lifted ideas and scenes for this book from After London (1885), by the English writer Richard Jeffries.

- Gregory Casparian’s An Anglo-American Alliance (1906). In 1960, Aurora Cunningham, daughter of Great Britain’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs, and Margaret MacDonald, daughter of an American senator, meet at a Ladies’ Seminary and fall in love. However, because they fear social ostracism and negative publicity — Western culture hasn’t caught up with the advanced technology; for example, prenatal sex determination and suspended animation are now possible, a germicide for laziness has been developed, and a Persian astronomer has discovered a new planet on which live a race of electric-wheel-riding aliens — the young women must suppress their true emotions. After graduation, Margaret becomes distraught and ill because she can’t be with Aurora. So — with a brilliant doctor’s help — she undergoes a “mental and physical metamorphosis” transforming her into a man: Spencer Hamilton. Spencer and Aurora marry, and live happily ever after.

- Alexander Kuprin’s Tost (The Toast), set in 2906, which praises the coming socialist revolution. A thousand years in the future, all humankind is joined in one Electro-Earth-Magnetic Association. Life is good: “Our work is a pleasure. And our love, freed from all the chains of slavery and vulgarity, is like the love of flowers: it is so free and beautiful. And our only master is the human genius!” However… life has becoming boring and joyless, in utopia. The people of 2906 languish in their glass palaces and feel nostalgia for the revolutionaries of a millennium earlier: “people with burning eyes, heroes with fiery souls.” All of which reminds this reader of the amazing movie Zardoz. Fun fact: In 1909–1910, Kuprin made an air balloon flight with a renowned sportsman Sergey Utochkin, then ventured into the Black Sea depths as a diver and accompanied the airman Ivan Zaikin in his airplane trips.

- Sue Greenleaf’s Don Miguel Lehumada, Discoverer of the Liquid from the Sun’s Rays (version pub. 1901 as Liquid from the Sun’s Rays). Greenleaf was an American feminist. In a future world where Mexico has been annexed to the US and the Earth’s axis has shifted, a Mexican scientist discovers that the sun’s rays can be focused into a liquid form called “Memory Fluid”. This, when ingested, has the ability to cure diseases, to evoke inner essences so potently truthful that they can cause suicide in their fleshly selves, and to serve as a new power source for the better world that may be about to reveal itself in the year 2050, after Lehumada becomes President.

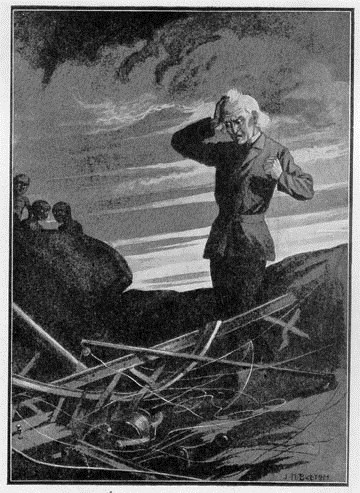

- John Mastin’s The Stolen Planet. Features the picaresque adventures of two Earthmen who, after Earth has been shaken by a vast disaster, undertake a fantastic voyage through the solar system and beyond, as narrated by Jervis Meredith, co-developer of an “aerostat” capable of space flight. The author was a clergyman and science popularizer. This and his other proto-sf books are told in the uplifting manner typical of too many UK boys’ books; they are permeated with religiosity, at times attempting a reconciliation of science and religion.

- Barry Pain’s Robinson Crusoe’s Return — satirical novel in which Crusoe is immortal. Revised in 1921 as The Return and Supperizing Reception of Robinson Crusoe of York, Parrot-Tamer. Pain is best known for the supernatural tales assembled in volumes like Stories in the Dark (1901) and Stories in Grey (1911), and for humorous fiction in which he uneasily condescended to the lower orders. Note that he would again deploy Gulliver in the titke story of The New Gulliver and Other Stories (1913), which takes its hero to a futuristic utopia… where he fails to gain happiness.

- Don Mark Lemon’s story “The Essence of Advertising” — in The Black Cat. A salesman offers a dry goods merchant a remarkable spray supposedly extracted from the thoughts of advertising geniuses. It works! But was it just a chemical compound of some sort?

- David M. Parry’s The Scarlet Empire.A critical response to H.G. Wells and socialism. A socialist who spends time in Atlantis (a socialist dystopia) changes his views, and becomes a financier instead.

- Frank L. Pollock’s “Finis” — in The Argosy — in which deadly radiance generated by a giant star at the center of the universe causes the end of the world. His most famous story; Ashley calls it one of the best early stories for The Argosy. Serialized at HILOBROW in 2021.

- George Griffith’s The Great Weather Syndicate — in which Americans and English entrepreneurs combine to use the invention of weather control to tyrannize Europe. Bleiler: “The usual lamentable period values, sensational treatment, and literary limitations.”

- George Allan England’s “The Lunar Advertising Co, Ltd” — in The Gray Goose — in which advertising matter is reflected from the Moon. A lesser work. Is it the same story as “A Message from the Moon” (1907) — in which the The Lunar Advertising Co., in 1930, projects an advertising message on the moon via enormous parabolic reflectors? I assume so.

- Florence Edith Austin’s “A Missile from Mars” in The Monthly Story Magazine, (vt. The Monthly Story Blue Book), August 1906. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- H.G. Wells‘ In the Days of the Comet — in which humanity is “exalted” when a green comet causes the air we breathe to become a happiness-producing drug. William, a young socialist and atheist who is at that very moment chasing the women with whom he is obsessed and her lover, discovers that he now only desires to help others. Everyone else feels the same way, and an era of post-ideological harmony ensues… compare with the ending of Doyle’s The Poison Belt (1913). Bleiler calls it the most personal of Wells’s early novels Wells’s open endorsement of polyamorous love at the end of this book caused some scandal. Listed in the Science Fiction After 1900 timeline

- Rafael Zamora y Pérez de Urría’s Crímenes literarios (Literary Crimes). Describes robots and automata as well as a “cerebral machine”, an artifact very like our modern laptop computers.

- Ludwig Hevesi’s “Jules Verne in der Hölle: Ein Brief des verstorbenen Schriftstellers an den Herausgeber” (Jules Verne in Hell). A humorous sketch, in which the French scientific romance titan Verne adventures in heaven and hell. Collected in Die fünfte Dimension. Check out the terrific book design (above). See 1901 for info on the author’s MacEck’s sonderbare Reise zwischen Konstantinopel und San Francisco. Fun fact: The author (Ludwig Hirsch) was Austrian.

- F. L. Keates “Man in the Air” in Scrap Book. First use of the term “antigravity.” Excerpt: “A disk of platinum coated with my new preparation, in which, I may say, radium plays some part, has a propelling power of immense force. I say ‘propelling power,’ but between you and me, I don’t think that conventional term properly applies to the strange force. For want of better name I am temporarily referring to it by the ridiculous and wholly inadequate name of ‘Anti-Gravity.’”

- Karen Bramson’s Dr. Morel. Originally published in Danish; translated into English by David Stanley Alder as The Case of Dr. Morel, 1926. Published in English as Dr. Morel, 1927.See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- J. Henry Harris’s A Romance in Radium. SFE calls it an “uneasily fin-de-siècle sf novel.” Follows the investigative journey to Earth of a feathered and winged female alien named Ma-Myliita, a member of the angel-like Murani from 100,000,000 miles away; her people are confused as to why Murani visitors, who arrived 5000 years earlier, remained on our planet and became mortal. The answer is sex — or, as Harris puts it, marriage. Angels cannot get enough of “marriage.”

- M.P. Shiel’s The Last Miracle — the first written and last published in a loose trilogy of apocalyptic tales (the others being The Lord of the Sea and The Purple Cloud — both 1901). In the not too distant future, an influential Continental figure (Baron Gregor), a modernist who — like Shiel — is convinced that Christianity is holding back progress, spearheads a plot to discredit Christianity with fake miraculous visions created by gigantic hologram-like devices. He is also manipulating a group of aggressive clerics, his patsies. (Before you side with the Baron, note that the sort of progress he champions includes sterilizing the unfit.) He sets off a great religious revival… but instead of doing away with religion, he accidentally sets into motion a new religion centered around the Overman! Reissued by Gollancz in 1929. Bleiler says: “Original, nicely written, and with good character studies.”

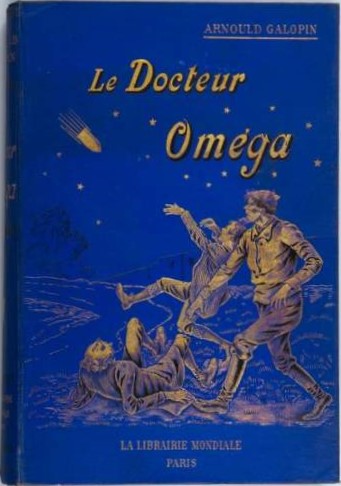

- Arnould Galopin’s Doctor Omega (French: Le Docteur Oméga) follows the adventures of the eponymous scientist Doctor Omega and his companions in the spacecraft Cosmos. The novel takes place in an unidentified village in Normandy, then later takes the reader to Mars. The main protagonist, Doctor Omega, is the mysterious inventor of a projectile-shaped spacecraft which can also function on land and under water. Cosmos is made from a substance called stellite or repulsite (depending on the edition) which repels space and time and enables it to travel in the aether. Can I just say — I’ve seen Wells credited as the author’s inspiration, but the plot and characters bear comparing to those of Alfred Jarry’s Dr Faustroll (w. 1898, first published posthumously in 1911). Fun fact: Galopin was the creator of Tenebras, the Phantom Bandit, a rival of Fantômas; and he wrote one of the earliest Sherlock Holmes pastiches too.

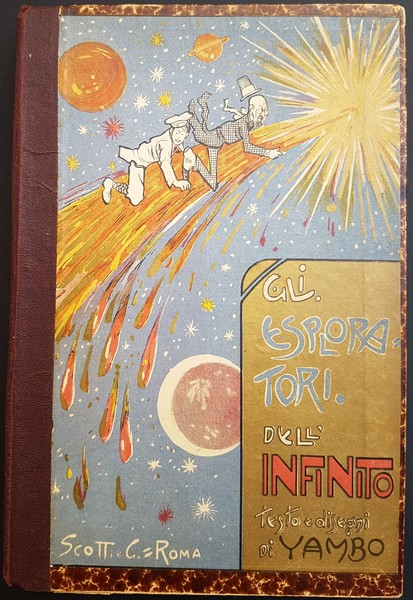

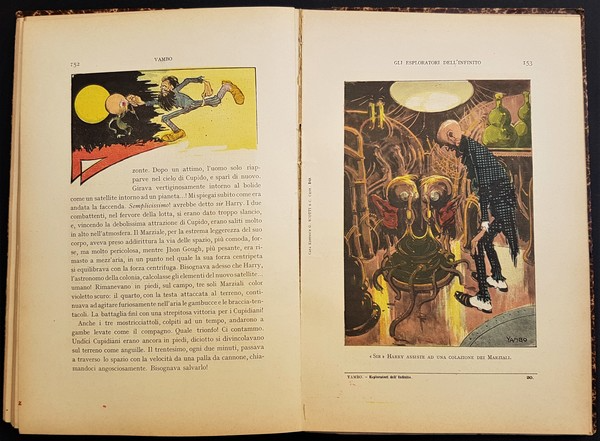

- Yambo’s Gli esploratori dell’infinito (Explorers of the Infinite). The author’s real name is Enrico Novelli. He also had a story called “Il ‘radium'” published 1904.

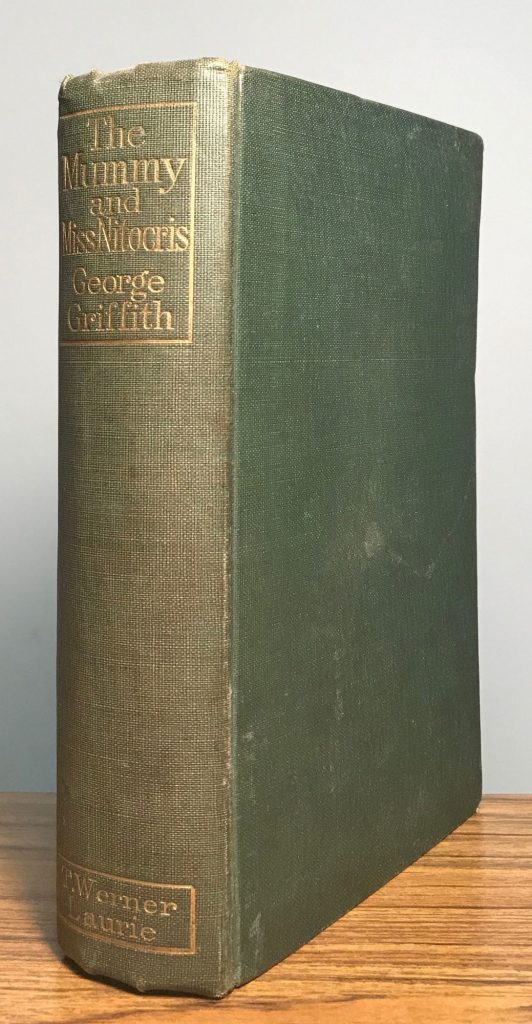

- George Griffith’s The Mummy and Miss Nitocris: A Phantasy of the Fourth Dimension — Bleiler says “Probably one of the most discordant mishmashes of disparate motifs ever perpetrated.” “Science fiction novel of flying machines, an averted world war and the fourth dimension which is built up from two earlier stories, ‘The Vengeance of Nitocris’ and ‘The Conversion of the Professor.'” – Locke, A Spectrum of Fantasy

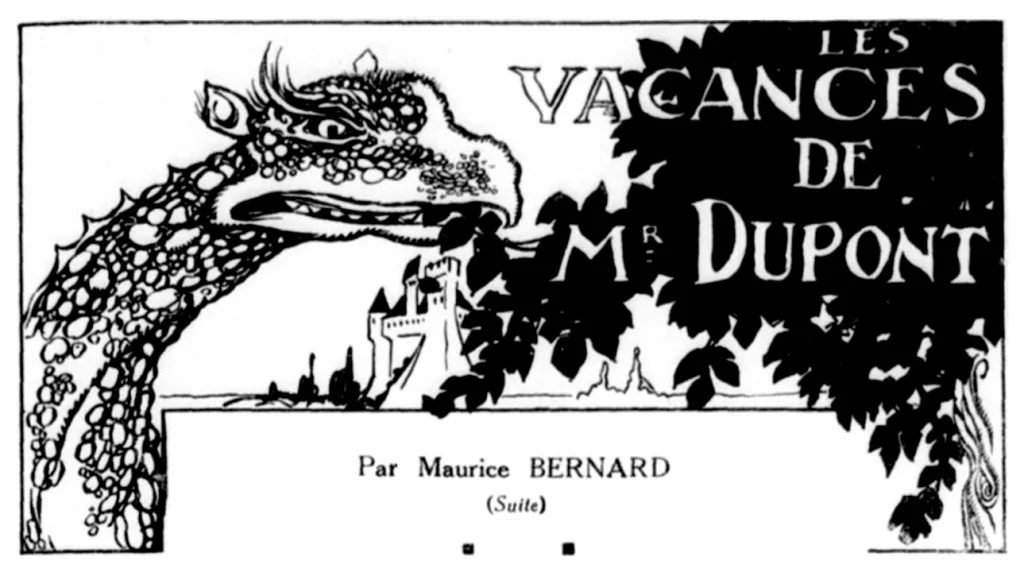

- Maurice Renard’s proto-Jurassic Park novella Les Vacances de M. Dupont. A recently discovered cave in southern France is found to contain huge dinosaur eggs. Due to a variety of climatic and geologic factors, they have been perfectly preserved. The eggs unexpectedly hatch, and the giant saurians wreak havoc not only on the surrounding countryside and on the paleontologist studying them, but also on the mild-mannered Dupont who had ironically decided to be spend a quiet vacation on his friend’s rural estate.

- Dorothy Adelaide Hilton’s “The Professor’s Mistake” in [British] Pearson’s Magazine, April 1906. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

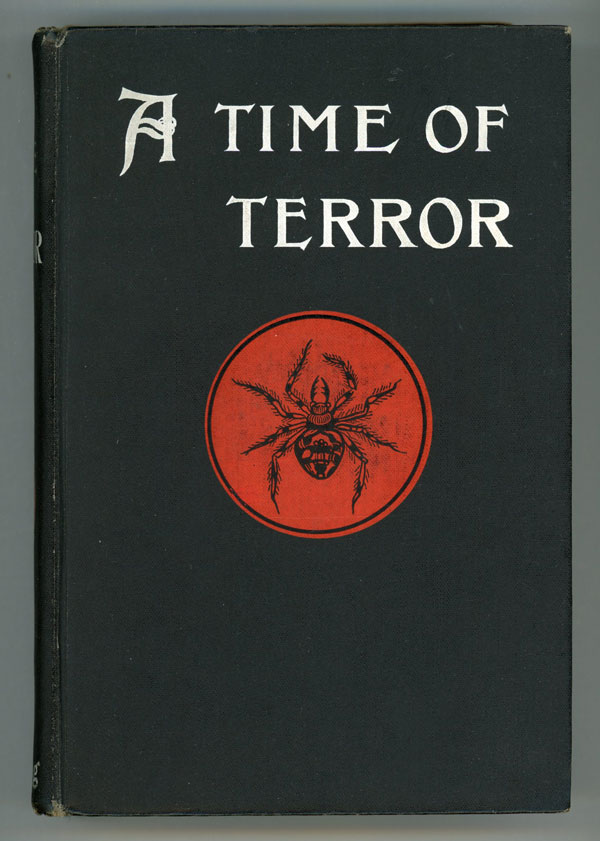

- Douglas Moret Ford’s A Time of Terror. The theme of this novel of future revolt of London’s poor, unemployed, and criminal elements is legal reform. The near victory of a secret society, the Leaguers of London, over law and order is thwarted at the height of nationwide violence by the outbreak of war between England and Germany and Russia. England is victorious and a patriotic and religious awakening destroys the power of the League. Clareson, Science Fiction in America, 1870s-1930s.

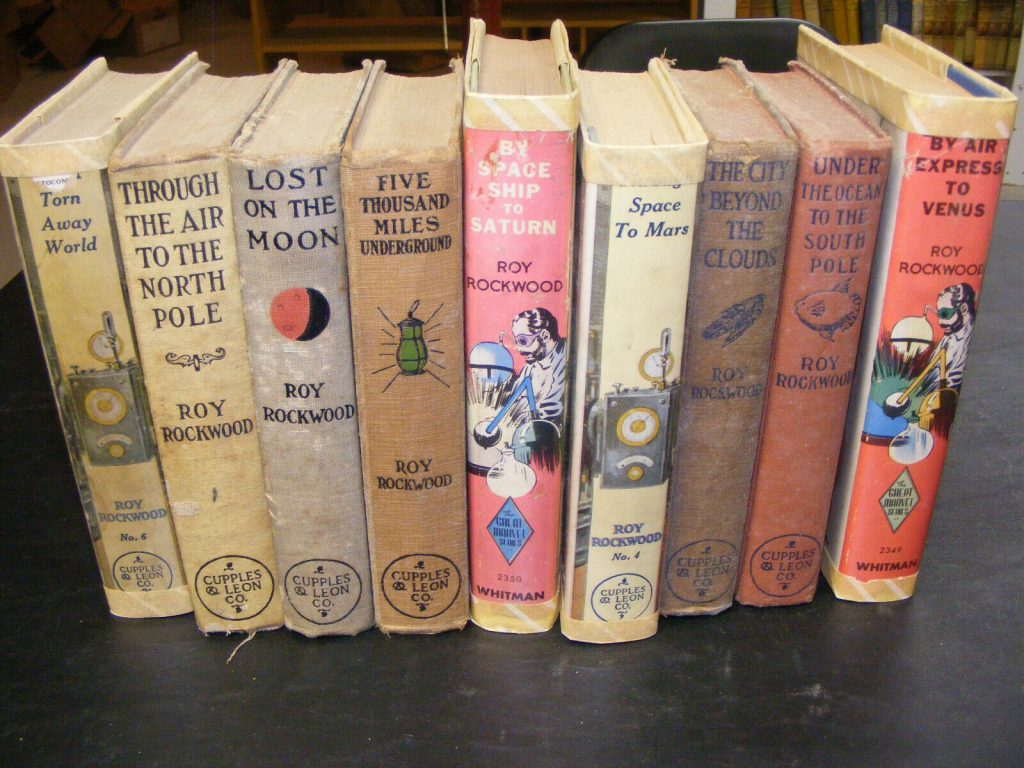

- Cupples & Leon’s The Great Marvel series (published under the house pseudonym Roy Rockwood) ran from 1906–1935, almost exactly coterminous with sf’s Radium Age. From a series advertisement: “Since the days of Jules Verne, tales of flying machines and submarine boats have enjoyed increasing popularity. Stories of adventures, in strange places, with peculiar people and queer animals, make this series noteworthy and popular.” One of the first products of the Stratemeyer Syndicate and its earliest venture into science fiction. Installments #1-5 and #8 were by the prolific Howard R. Garis of Uncle Wiggily fame.

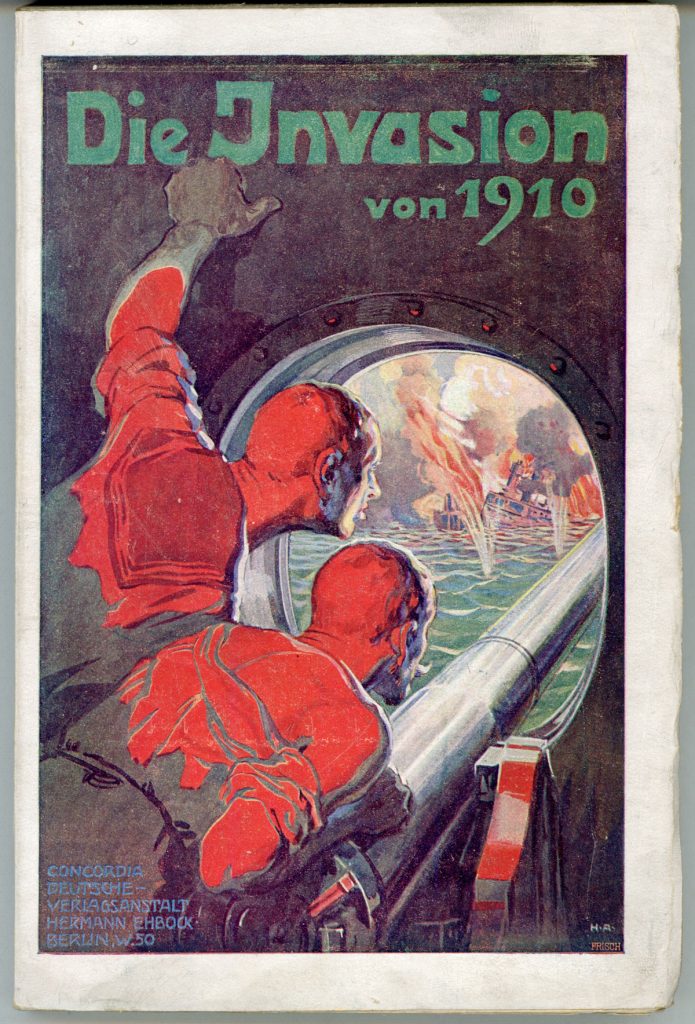

- The Invasion of 1910 is a 1906 novel written mainly by William Le Queux. It is one of the most famous examples of invasion literature, viewed by some as an example of pre-World War I Germanophobia. Here’s a German edition — terrific cover! The heads and shoulders of these German sailors are bathed in a fiery glow — which makes them look like space-suited soldiers peering through the porthole of a galactic battle cruiser….

- The ‘?’ Motorist is a 1906 British short silent comedy film directed by Walter R. Booth. A couple on the run from the police comes to a building and their car drives up the wall, leaving an amazed crowd behind. The car drives past stars on clouds, around the Moon, and around the rings of Saturn before crashing through the roof of Handover Courthouse. Silly.

ALSO: In 1906 the neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington identifies proprioception, our ability to perceive ourselves in space — “our sixth sense.” (The phrase “sixth sense” would be appropriated by occultists, who used it to describe the mediums ability to perceive things in the same space but in different dimensions.) Amundsen (with crew, shown above) traverses Northwest Passage; Nansen’s Norwegian North Pole Expedition 1893–1896. All India Moslem League founded by Aga Khan. Blackwood’s The Empty House, Sinclair’s The Jungle, Jack London‘s White Fang. Rosa Luxemburg’s pamphlet, “The Mass Strike.”

Percival Lowell’s Mars and its Canals present a popular version of the astronomer’s position that Mars is a habitable planet. This is the second of three books he wrote on the topic; the others are Mars (1895); and Mars as the Abode of Life (1908). His thesis: Schiaparelli’s canals were actually the irrigation channels of an advanced civilization that funneled water from its polar caps in accordance with seasonal demand and a changing climate. Influential on the era’s proto-sf. See images here.

Also in 1906, Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint paints her first series of abstract paintings. Klint assumed that there was a spiritual dimension to life and aimed at visualizing context beyond what the eye can see. Influenced by spiritualism and theosophy, she sought to understand and communicate the various dimensions of human existence. She felt that The High Masters, spirits with whom she communed, had assigned her to create paintings for “the Temple.” Between 1906 and 1915, she painted nearly 200 works; this was carried out in two phases with an interruption between 1908 (because Rudolf Steiner had discouraged her) and 1912. She developed an inventive geometric visual language — grids, circles, spirals and petal-like forms (sometimes diagrammatic, sometimes biomorphic) — capable of depicting invisible forces both of the inner and outer worlds. PS: When I saw Klint’s epic 2018 show at the Guggenheim, I realized, “Aha! The Guggenheim is the ‘Temple’ for which Klint was painting.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin