RADIUM AGE: 1911

By:

July 3, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

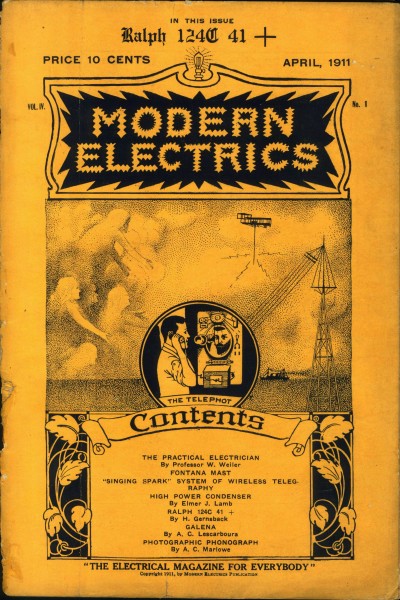

Facing steep declines in circulation, the Munsey magazines go fully pulp — lurid covers. This is also the year that Gernsback begins publishing (in his magazine Modern Electrics, created in 1908 to promote the amateur radio hobby) technology-based fiction stories. The first fiction appeared in the April 1911 issue (shown above), and the series of 12 installments by Hugo Gernsback would later be published as the novella Ralph 124C 41+.

In 1911, The Cavalier introduced The Occult Detector, written by Salt Lake City doctor, J.U. Giesy, and Cincinnati lawyer, Junius B. Smith, featuring Semi Dual, a detective who uses psychic sciences to solve cases. This series became a staple in Munsey pulps for over twenty years.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1911.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1911, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: EARTHGIRL | PORTHOLE (a small window in a spacecraft) | SPACE FLYER.

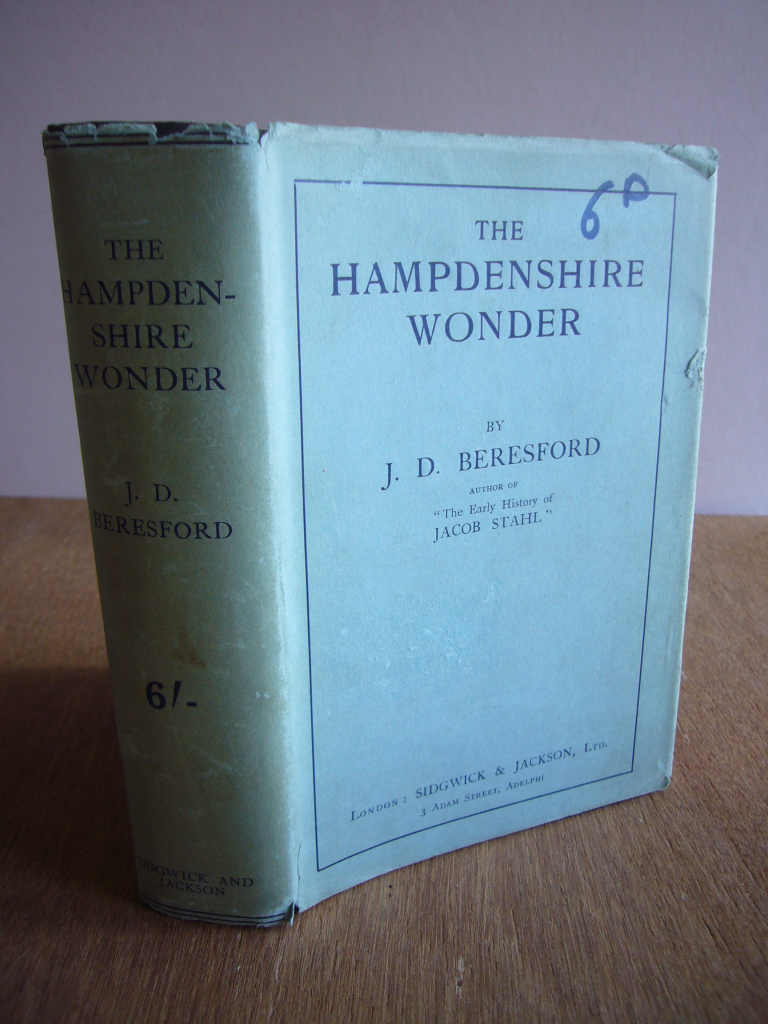

- J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder. Victor Stott is a giant-headed “supernormal” child mutated — in the womb — by his parents’ desire to have a son born without habits. After surveying science, philosophy, history, literature, religion, the best that has been thought and said, the Wonder is dismissive: “So elementary… inchoate… a disjunctive… patchwork.” Young Victor’s adult interlocutors are shattered by his statements about the nature of the universe and human progress; his philosophy begins with rejecting “the interposing and utterly false concepts of space and time,” and ends with the notion that life and all matter are merely “a disease of the ether.” Alas, his interlocutors are unable to live without illusions; they reject the Wonder’s disenchanting insights. Worse, the superboy also makes an enemy of the local clergyman, who (the reader is left to suspect) murders him. The narrator’s eulogy: “He was entirely alone among aliens who were unable to comprehend him, aliens who could not flatter him, whose opinions were valueless to him.” Fun fact: It’s been called the first SF novel of real importance about intelligence; but also see discussion of M.P. Shiel’s The Isles of Lies in 1909 entry. Serialized at HILOBROW in 2022.

- Marie Corelli’s The Life Everlasting (1911), where the recent discovery of radium shapes the mechanics of phantasmal machines and psychic forces able to pass through all impediments. See this post at the Public Domain Review.

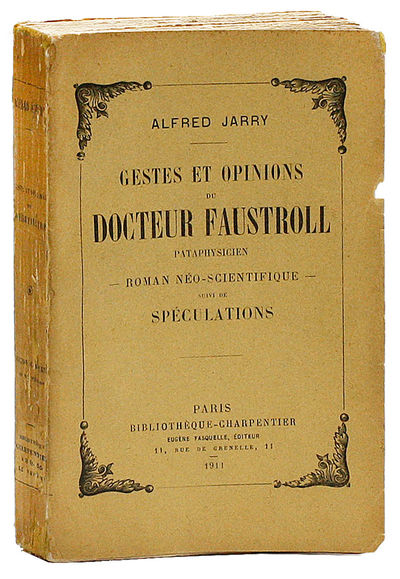

- Alfred Jarry’s Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique suivi de Spéculations (w. 1898, p. 1911, trans. as Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician). The scientist-inventor Dr. Faustroll travels — in a high-tech (capillarity, surface tension, equilateral hyperbolae are involved) amphibious copper skiff — from the Seine from point to point through the neighborhoods and buildings of Paris. He is accompanied by his Wookiee-like baboon butler Bosse-de-Nage, and also by the story’s narrator, Panmuphle, a lawyer attempting to convict the good doctor of debt. Opposed to mainstream science’s principe de l’induction, Faustroll practices a “science of imaginary solutions” that he calls ’pataphysics. Whereas the inductive reasoner brackets his imagination and blinkers his perspective, the ’pataphysician embraces as many perspectives as possible; no conjecture is regarded as impossible. Spoiler alert: Dr. Faustroll dies! But he manages to send a telepathic letter to Lord Kelvin describing the afterlife and the cosmos. Fun fact: Jarry is best known as the author of the proto-Dada play Ubu Roi. This posthumously published novel is regarded, by exegetes, as the central work to his oeuvre.

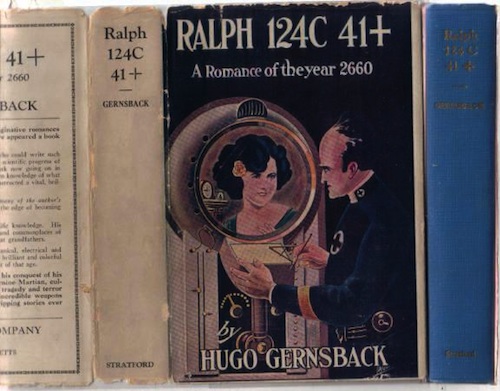

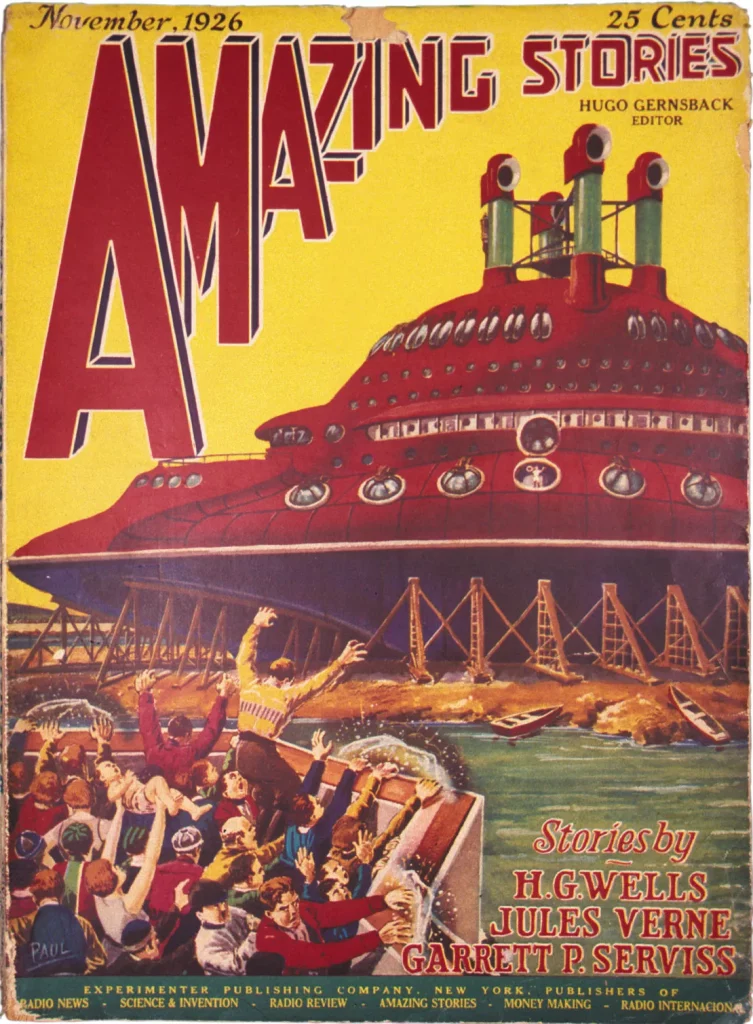

- Hugo Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660 (1911–1912). Ralph One-to-foresee-for-an-other (get it?) is a great American scientist, and a superior type; the honorific “plus” at the end of his name signifies it. But what kind of big-headed superman story is this, anyway? The polar fleece-wearing citizens of solar-powered, geothermally heated New York don’t fear or resent Ralph; in fact, they’ve erected a glass-and-steelonium luxury tower for him in Union Square. Ralph isn’t an evil genius; he’s something of a bore, and so is his techno-utopian society. Except maybe when his girlfriend is kidnapped by a Martian! Despite the wooden prose and juvenile adventure, this Edisonade is worth a read because of all the technology it accurately predicts: e.g., fluorescent lights, microfilm, radar, television. Also, I suspect that we’re on the cusp of seeing the Hypnobioscope, which allows you to avoid subscribing to newspapers in your sleep, hit the Apple Store. Fun facts: Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination. In 1926, Gernsback launched the first sci-fi pulp, Amazing Stories; later, he’d also publish Wonder Stories. Science fiction’s Hugo Award is named after him.

- Mark Wicks’s To Mars Via the Moon — describes a journey to the moon and Mars in the anti-gravity spaceship Areonal. Heavily influenced by the work of Percival Lowell. Wicks was an amateur scientist and tinkerer who was enamored with the study of Mars. The first half is practically just a textbook of known information and recent scientific debate as of 1910 about our lunar baby sister and our Martian older brother. Wicks puts forth the noble effort of couching his scientific summaries in a loose fantasy plot about three guys traveling to Mars in their homebrewed spaceship. The second half concerns the first contact of the three explorers with Martian civilization. Here the book becomes pure speculative fiction, reminiscent of the popular socialist propaganda fantasies of the era. Dull, when not unintentionally hilarious. PS: Wicks was one of the believers that the canals were real technological innovations of either an existing or past intelligent civilization, but he admitted that a more accepted belief in his day was that the canals are optical illusions which is what is generally accepted today after the Rover landings. PPS: Scottish engineer — one of the era’s prototypes for Scotty of Star Trek. “I have switched on more power, but it does not seem to make any difference!”

- Algernon Blackwood’s The Centaur — one of his novels of occult pantheism, this one builds on the theories of Gustav Fechner in its projections of a sentient Mother Earth. Set in the Caucasus between the Black and Caspian Seas, The Centaur centres on Terence O’Malley, an Irish journalist of mystical temperament who is studying the peoples of the area. O’Malley, at odds with the pace and materialism of the modern world, rejects this way of life and instead countenances a return to nature which he interprets as a sense of kinship with the universe. When traveler O’Malley encounters an unusually robust, handsome, and virile man and his equally attractive young son while on a cruise, he becomes strangely enraptured, and is thrilled to learn that the two will be sharing his cabin for the duration of the voyage. O’Malley also notices that when observing the two men from a distance, they seem to oddly amalgamate into one larger being, or, at other times, an immense third presence seems to accompany them. Is it a trick of the light? Is O’Malley a lunatic, hallucinating, or experiencing repressed homosexual desire without realization? Also along for the voyage is the learned Dr. Stahl, who inexplicably has a great understanding of the two strangers and what they threaten. Blackwood allows himself almost a hundred repetitive pages attempting to convey to the reader the secret Dr. Stahl attempts to put succinctly into words. The father and the son, as it happens, are not men in the sense that Stahl and O’Malley are men, but are earth spirits, pure emanations of nature, and, as such, two of the last beings of their kind in existence. This mystical novel weaves a fascinating tale while, at the same time, making a passionate plea for a lifestyle that is closer to nature. As one Amazon review puts it: “This novel’s great revelation is pretty easy: back to simplicity & we’ll make it back (or near) to the Garden of Eden. Blackwood’s unveiling of this truth is anything but simple–more like repetitive, awkwardly circular reasoning, even condescending.” Here Blackwood argues a logic of history which seems sufficiently rational to count as proto-sf. S.T. Joshi calls this novel the `cornerstone’ of the entire Blackwood canon, and this seems to be a fair assessment of this intensely philosophical work; this could easily constitute an instruction manual in Blackwood’s world-view. PS: Not to be confused with The Centaurians — see below.

- L.D. Biagi (pseudonym of Lottie F. Ambrose?)’s The Centaurians. The construction of a curious vehicle called ‘The Propellier,” which is similar to Edgar Rice Burroughs’ ‘Iron Mole’ used in the Pellucidar adventures, is used to carry the heroes across the Arctic ice and water to an unknown land beyond the North Pole. The land is populated by two warring semi-barbaric races and the ‘Centauri,’ a highly advanced race, whose achievements in the arts and sciences go beyond that of Europe and the USA. In one part of the story, the hero is taken into outer space ; the goal is the Moon but they do not make it.

- Stojan Novaković’s “Posle sto godina” (“After One Hundred Years”). Novaković (18421915) was a Serbian politician, historian, diplomat, writer, bibliographer, literary critic, literary historian, and translator. He held the post of Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Serbia on two occasions.

- Robert Ames Bennet (writing as “Lee Robinet”)’s The Forest Maiden. A novel of fantastic adventure set in the back woods of British Columbia, with utopian/dystopian aspects. Adam, the leader of his three-person community, has extraordinary powers of telepathic mesmerism over both humans and animals. He can also induce scrying and articulate speech in his two-year-old child. He can shape-shift into a wolf and can also walk on water. With absolute and tyrannical power he rules his consort, Eve; their precocious baby; and a beautiful 18-year-old with golden red hair, Lilith. Juxtaposed to their Neolithic technology is a science-fictional powder that Adam cooks up in his cave laboratory: it deadens the scenting power of animals and thus protects a human in the wilderness. The story’s hero, Kenmore, on holiday with his half-breed guide, gets lost and chances upon Lilith. She warns him to go back but the hero is already falling in love with her and is not content to leave until he can take her with him. Before then he must match wits and wills against Adam, a feral human who develops extraordinary powers on returning to a primitive natural state. His two female subjects, are also quite extraordinary — English aristocrats in their previous lives. The model of Nietzsche’s superman is also invoked more than once in connection with Adam. “A fine novel with a mixture of thrills and thought-provoking ideas, and a style that is precise, unsentimental and compulsively readable (not a common virtue for fiction of this period).” – Robert Eldridge.

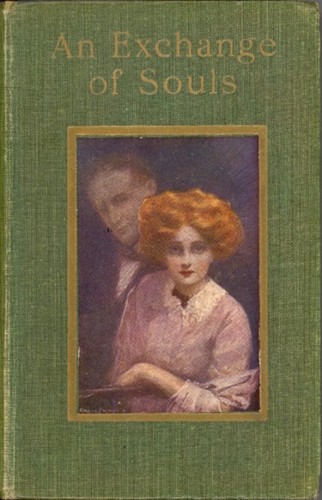

- Barry Pain’s An Exchange of Souls — a scientific rationale is posited for the said identity exchange. Respected doctor Daniel Myas is a scientist who has developed a machine which allows for the exchange of his “personality” with that of another. However when his attempt at “exchanging souls” occurs with an individual very close to him, only a form of horror can be the result, and the reader is led down a path of deterioration and fear. Undoubtedly this novel, published in 1911, influenced H.P. Lovecraft’s tale of personality exchange in “The Thing on the Doorstep,” published in 1937. Pain’s development of the theme of immortality by use of scientific methods proves quite difficult, and at the same time quite intriguing. What are the potential results when ‘souls’ are exchanged, particularly with those of the opposite sex?

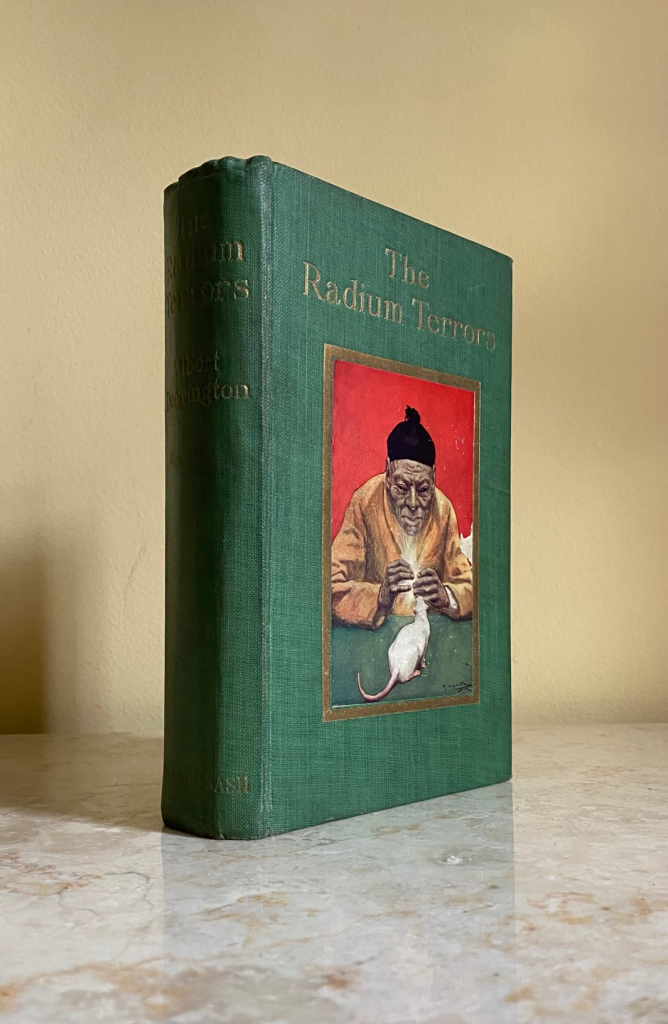

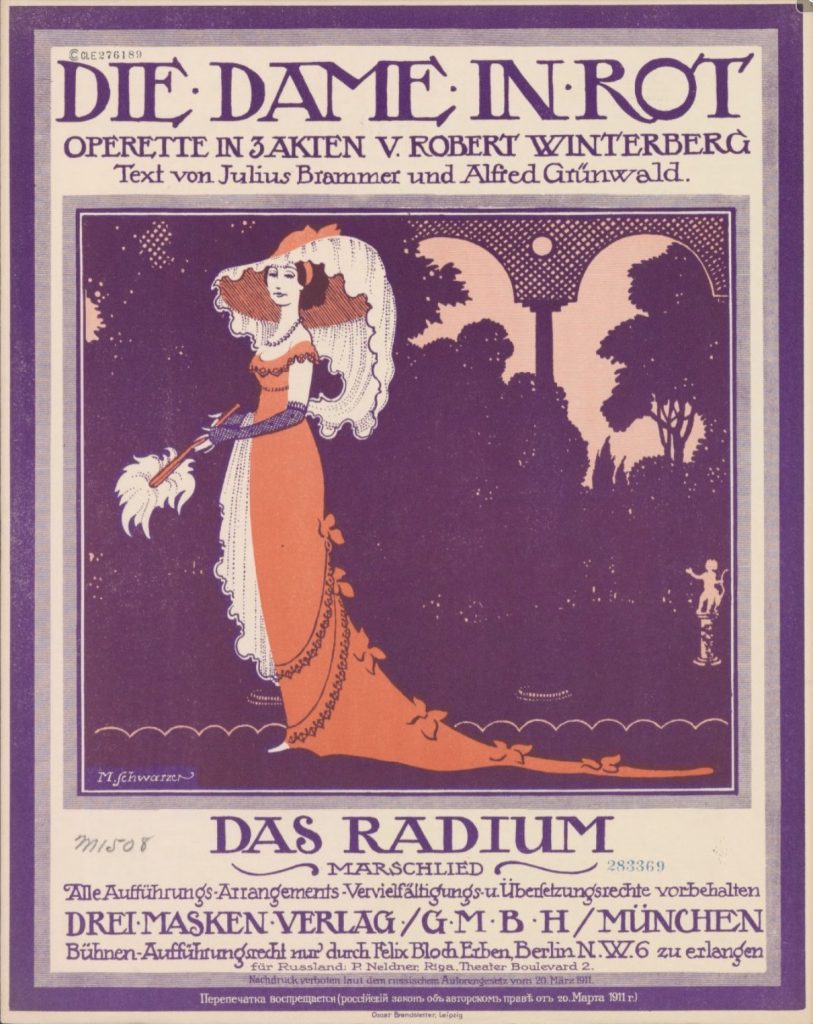

- Albert Dorrington’s The Radium Terrors. Sensational mystery thriller, very popular in its day, about the harmful and curative properties of radium, with a “Yellow Peril” villain reminiscent of Fu Manchu (but Japanese) who has stolen radium to further his sinister plot. Combining the Yellow Peril threat with the contemporary fascination over the powers of radium. Read it here.

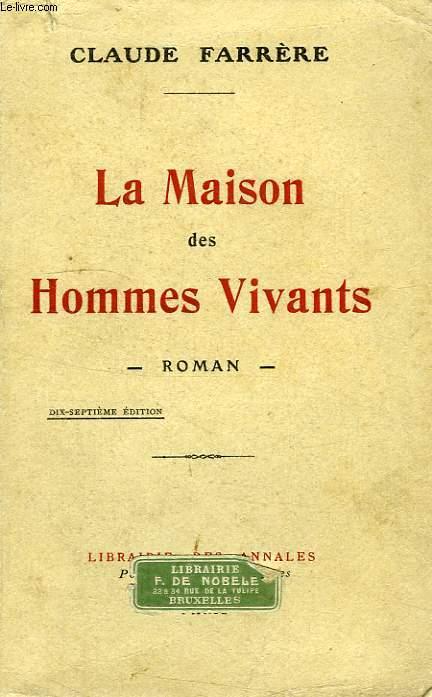

- Claude Farrère’s La maison des hommes vivants (trans. Arthur Livingston as The House of the Secret 1923), about experiments in longevity. Sensational thriller of immortality; disciples of Saint-Germain draw youth and vitality from their living ‘guests’ in an isolated castle. A novel of psychic vampirism.

- Beatrice May Butt’s The Laws of Leflo. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Cora Minnett’s The Day after To-Morrow. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Emilia, condesa de Pardo Bazán’s “Cometaria” (Spanish). In La Ilustración Española y Americana (The Spanish and American Enlightenment),See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- John Buchan’s “Space” (May 1911 Blackwood’s Magazine) presents the concept that the “corridors of space” shift constantly according to arcane and terrifying mathematical principles.

- Baroness Bertha von Suttner’s Der Menschheit Hochgedanken (translated 1914 as When Thoughts Will Soar). An antiwar novel by Suttner (1843-1914), an Austrian novelist, radical pacifist and winner of the 1905 Nobel Peace Prize, set in a future “Age of Flying” in which the “Rose Order” brings about world peace. famous Austrian pacifist Baroness Bertha von Suttner. The story of a scientific conference whose participants, by the sheer brilliance of their thought, ward off war and preserve world peace. The author published an earlier, very influential, antiwar novel, Die Waffen Nieder! (1889). See Geert Somsen’s essay “The princess at the conference: Science, pacifism, and Habsburg society.” Relating the novel to von Suttner’s own life experiences, Somsen suggests that Von Suttner mobilized notions of the pacific effects of science with an eye to preserving both the European system of states and the position of the aristocracy.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “The Generations of His Forefathers.” Drugs send a man into past.

- Edith Nesbit’s Dormant (as Rose Royal, 1912) is a fantasy-tinged sf novel involving suspended animation. The form of immortality bestowed by the protagonist, who has been “awakened” after half a century, proves a mixed blessing. Begins as a comedy about a group of struggling young people: an artist, a chemist, an editor, doctor, a journalist, a dressmaker, and a young man who lives off his father’s pesticide money. They call themselves the Septet and eat, drink, and debate capital punishment and women’s suffrage. The heroine, Rose Royal, is a likable, kind, pretty artist with a small private income. In London She rents Malacca Wharf, where she inhabits a dilapidated house and rents a decrepit warehouse to her chemist friend Anthony. The novel morphs into a feminist horror retelling of Sleeping Beauty, when Anthony experiments with an elixir of life. The dead body of a girl named Eugenia is found in the laboratory. When Anthony brings her back to life, is she grateful to be awake?

- George Griffith’s The Lord of Labour — published posthumously. Another of the prolific author’s extravagant future-war stories, this one featuring atomic missiles and disintegrator rays.

- Jean de La Hire’s Le Mystère des XV (trans. as The Nyctalope on Mars). Léo Saint-Clair, alias the Nyctalope, is an indomitable Doc Savage-style crimefighter gifted with night vision. He appears here for the first time (not in the 1908 book L’Homme qui peut vivre dans l’eau). As we learn somewhat late in the series, he’s also equipped with an artificial heart, which he gained after being tortured and nearly assassinated, and which prevents him from aging. In this, the first of a series of exploits published through the mid-1940s, the Nyctalope battles Oxus, leader of the sinister Society of the Fifteen, who is plotting to conquer Earth from his secret base on Mars. Later, however, he allies himself with Oxus and the planet’s benign inhabitants in order to defeat H.G. Wells’ evil Martians. Then he gets married! Fun facts: French title: Le Mystère des XV. In subsequent adventures, the Nyctalope will travel to the planet Rhea, discover a lost civilization of Amazons in Tibet, and have himself cryopreserved — so that, 170 years later, he can defeat an enemy who has also been frozen (hello, Demolition Man and Austin Powers). MORE ABOUT DE LA HIRE.

- Henry Darger’s In the Realms of the Unreal (1911–39). Darger’s 15,000-page novel is bound in fifteen immense volumes, three of which consist of several hundred watercolor paintings on paper derived from magazines and coloring books. Most of the book, titled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, follows the graphically violent, epic adventures of seven princesses who assist a daring child-led rebellion against the evil regime of child slavery imposed by the Glandelinians. The setting is a war-torn planet around which the Earth orbits. The first nine volumes were most likely written between 1911 and 1928; the remaining volumes were completed by 1938 or 1939. Fun facts: Darger was a reclusive man who worked as a hospital custodian in Chicago; Darger’s landlords came across his work shortly before his death, in 1973, and preserved it. Darger is today one of the most famous figures in the history of “outsider art.”

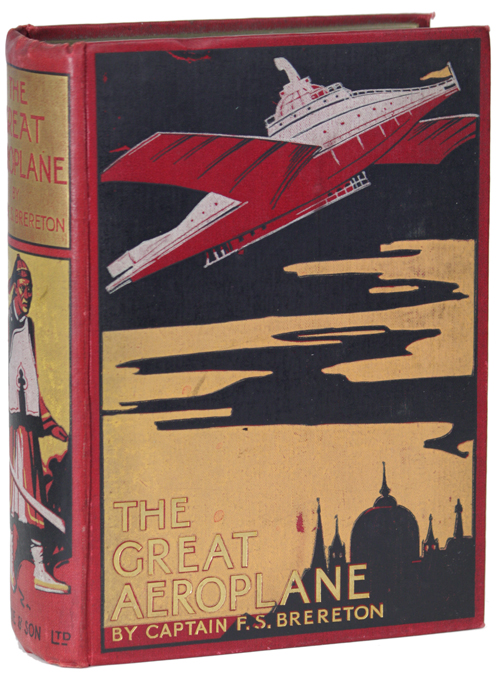

- F.S. Brereton’s The Great Aeroplane. Boys’ adventure tale moving from England (where the young protagonists befriend a scientist with an advanced jet powered by “broadcast” electricity) to Canada to Mongolia to Africa.

- François Léonard’s Le triomphe de l’homme, a Verne-like novel in which Earth is accidentally propelled from the solar system and drifts away into the universe until its final destruction. Belgian?

- R. Norman Grisewood’s The Venture: A Story of the Shadow World. An invention enables scientists to explore life in another dimensionp. Psits an identity transfer between our world and another, but less interesting (according to the SFE), plane of existence. Compare with his 1909 novel Zarlah the Martian.

- Garrett P. Serviss’s The Second Deluge (July 1911-January 1912 Cavalier). Described by Moskowitz as greatest single tale of sf published by the Munsey magazines up to that time. A disaster novel in which the Earth is inundated to a depth of several miles as a result of passing through a “nebula” composed of water; a latter-day Noah, having built an ark, saves all God’s creatures and visits the US West, where the president has also been saved. Listed in the Cambridge Companion to SF chronology. Fun fact: When the world’s first sf illustrator – Frank R. Paul – illustrated the cover of the world’s first sf magazine – Amazing Stories – in November 1926, it was a depiction of a scene from The Second Deluge. “In American science fiction, the catastrophe motif did not assume its fully developed form until the publication of The Second Deluge” – Alice Clareson, The Emergence of American Science Fiction: 1880-1915.

- Ford Madox Ford’s Ladies Whose Bright Eyes. Although it has a time travel theme of a sort, is usually classed as mainstream literature rather than sf. As its author explicitly stated, ” (…)The idea of this book was suggested to me by Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. It occurred to me to wonder what would really happen to a modern man thrown back to the Middle Ages…”. Unlike Twain’s Hank Morgan and some successors, Ford’s Mr. Sorrell makes only a very half-hearted attempt to build modern weaponry and machinery in the Middle Ages. His initial dream of constructing “guns and gas bombs” and making himself “mightier than kings” soon comes to naught. Though he had been a mining engineer in the twentieth century, he has no idea how to go about constructing such devices under fourteenth-century conditions, or even where there are tin deposits. Having later in his career become a publisher does not give him any idea of how to invent printing from scratch and anticipate Gutenberg. He does not know how to make a gun, or in fact anything that would make him useful in the medieval castle community into which he has fallen. Instead, Sorrell finds that a golden cross which he carries causes him to be mistaken for a Greek miracle-worker – which has many advantages in Medieval society, including enjoying the unlimited hospitality of a castle and having beautiful ladies vying with each other for his love. He also inspires the ladies to take up arms and hold a tournament in competition with their knightly husbands – and being a fair horseman, makes a credible effort at becoming a knight himself. It is the reverse of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, but the details of daily life are rendered more feelingly, including the quite earthy and mercenary motivations of many of the Medieval charactersWritten in 1911 and extensively revised in 1935.

- Gaston Leroux’s Balaoo is a proto-sf tale featuring a missing link in a detective role. Balaoo was first published in Le Matin in 1911, and in book form, first in a single volume edition, then in 2 volumes, both in 1912. The first and only English editions of Balaoo (1913, 1914) was originally titled The Mysterious Mr. Noel. Moskowitz says it is not very good.

- George Allan England’s The Elixir of Hate (August-November 1911 Cavalier). American physician Granville Dennison, who is not a sympathetic figure, abandons his medical practice and comfortable life in New York to sail across the Atlantic in search of a life-saving miracle. Rumor has it that a brilliant scientist living in seclusion may have discovered the secret of eternal youth. In the end, he gets what he deserves. A four part novel that presents more sophisticated characterization and ethical analysis than appears elsewhere in the author’s pulp-magazine work. Ashley calls it “remarkable.” Moskowitz says the story made it instantly clear that England was one of the best sf writers of the day.

- James Barr’s “When Women Won” — about the suffragette movement.

- James Barr’s “Lord Hagen’s Dress Suit” — about the threat of aviation. Advancing technology has a retrograde effect and forces people back into caves.

- M.P. Shiel’s first Cummings King Monk stories — “He Meddles With Women,” “He Defines ‘Greatness of Mind’,” “He Wakes an Echo.” (Together, these form the three-part “Cummings King Monk” section of 1911’s The Pale Ape and Other Pulses. Cummings King Monk is a kind of superman — a super-genius. There are sf-ish aspects to the stories.

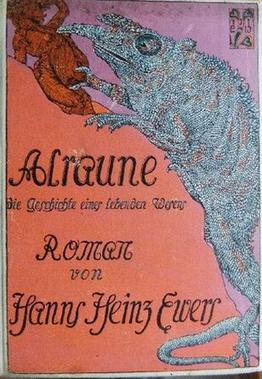

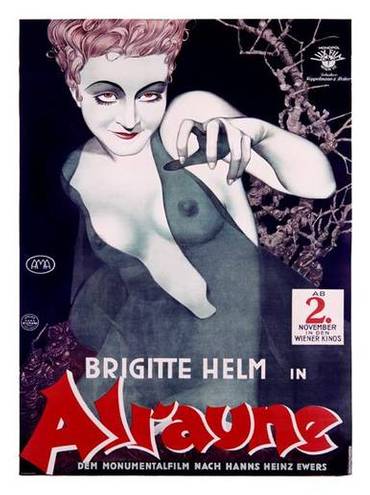

- Hanns Heinz Ewers’s Alraune. With the help of his ubermensch nephew, Frank Braun, scientist Jacob ten Brinken collects the semen of a condemned man (ejaculated at the moment of the man’s execution) and uses it to impregnate a prostitute. He is conducting a test of medieval German folklore about the fertility powers of the mandrake root, which was believed to be produced by the semen of hanged men under the gallows; witches who made love to the mandrake root, it was believed, produced offspring who had no soul. Alraune, the fruit of this experiment, cannot overcome her genetic inheritance: She is a sociopathic, perhaps vampiric child; and as an adult, she drives lovesick men — including Jacob ten Brinken — to ruin and death. However, Alraune meets her match in Frank Braun, who is worse than a vampire: He’s a lawyer. The novel’s final chapters are a catalog of the couple’s outrageous sexual practices. Fun facts: The book’s English translation was made, in 1929, by Guy Endore. This is the second of three Frank Braun novels, the others being The Sorceror’s Apprentice (1907) and Vampire (1927). An early member of the Nazi Party, Ewers alienated its leadership by insisting that the Nazi obsession with blood (genetics) led inevitably, properly, to vampirism.

- Otto Witt’s De sista människorna (The Last Humans). Swedish. Set some 20,000 years in the future, a world to which a twentieth-century engineer is transported by time machine to find most of the Earth covered in ice and the few remaining humans living in peace and comfort, but without any passion for life. The engineer hero finds a way to move the Earth closer to the sun, the ice melts, evolution again takes over and a new, more creative humanity is kindled. SFE says of Witt: “His narrow morality, bland writing style and nationalistic blindness make him at best a curiosity.”

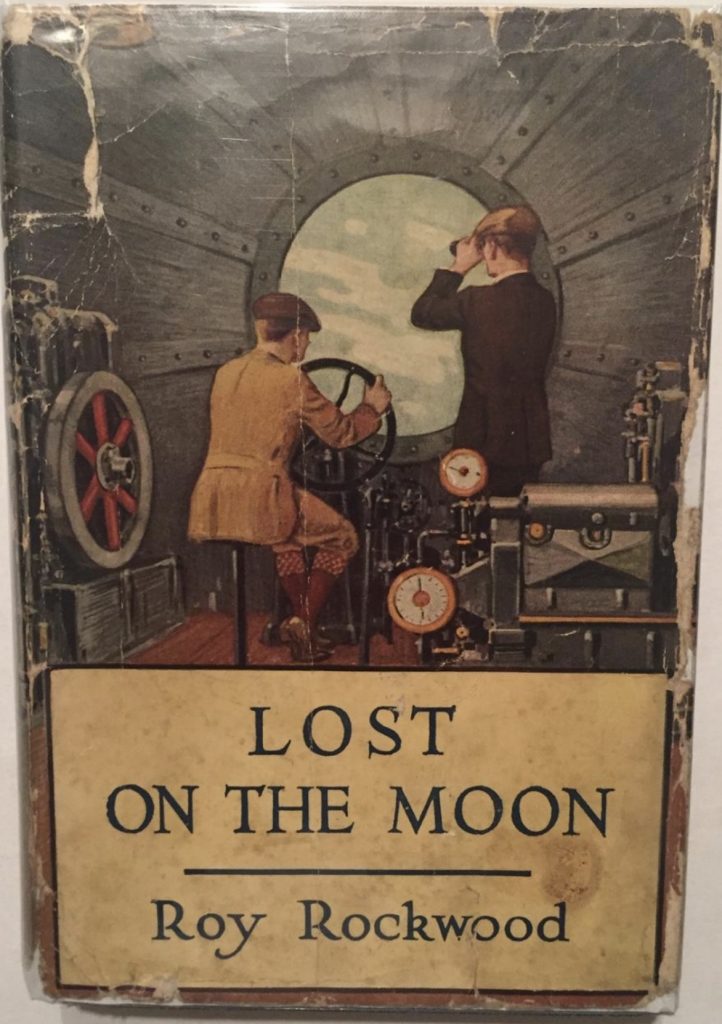

- Roy Rockwood’s Lost on the Moon; or, In Quest of the Field of Diamonds. “Roy Rockwood” was a house pseudonym used by the Stratemeyer Syndicate for boy’s adventure books. The name is mostly well-remembered for the Bomba, the Jungle Boy (1926-1937) and Great Marvel series (1906- 1935).

- Friedrich Mader’s Wunderwelten (1911; trans Max Shachtman as Distant Worlds: The Story of a Voyage to the Planets 1932) is a juvenile which takes its spaceship crew to Mars and finally — one of the first sf texts to indicate clearly that faster than light speeds would be required for rapid interstellar travel – to Alpha Centauri, where they explore an Eden-like planet. The spaceship is described as being vast, though the term “world-ship” applied to it should not be taken to seriously adumbrate the contemporary use of the term world ship. The content of the tale is quite advanced for 1911, and although it is not well written it plausibly established Mader as a significant figure in German sf along with Hans Dominik and Kurd Laßwitz.

- Perley Poore Sheehan’s “Monsieur De Guise” — mentioned in Moskowitz’s A History of the Scientific Romance as very well written, but is it a ghost story or sf?

- William Greene’s The Savage Strain. A story about a mutant super-genius, I think.

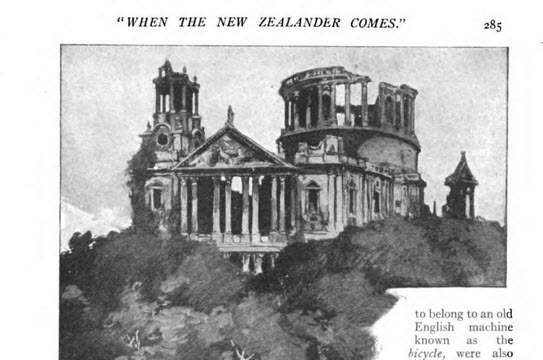

- Muddersnook (a nom de plume)’s “When the New Zealander Comes” — satirical story in which future archaeologists dig up London, and puzzle over what they find. Collected by Moorcock.

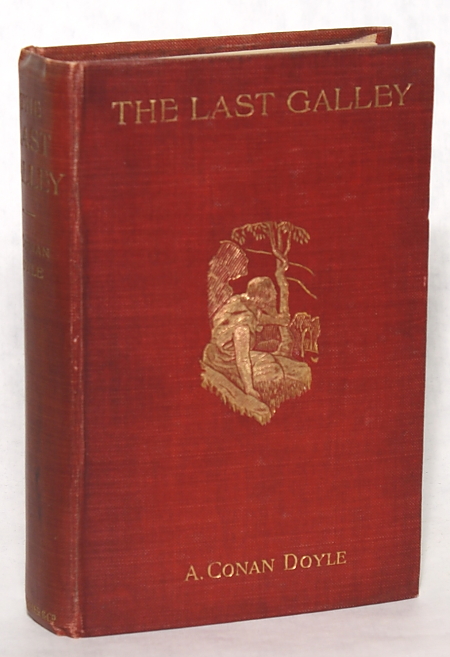

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Last Galley. Mixed collection of seventeen stories including “The Terror of Blue John Gap” and four other SF and fantasy tales.

- Kipling’s “In the Same Boat” (December 1911 Harper’s Monthly) suggests a prenatal cause for bouts of irrational dread — not unlike the “engrams” of Scientology.

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Moving the Mountain. Feminist utopia set in 1940. Gilman pointedly calls her book “a short-distance Utopia, a baby Utopia, a little one that can grow.” Gilman casts her protagonist into a reformed future, but without the “element of extreme remoteness” found in other books. (Gilman’s fictional transformation of America has its dark side: one informant explains to John Robertson that “We killed many hopeless degenerates, insane, idiots, and real perverts, after trying our best powers of cure.”)

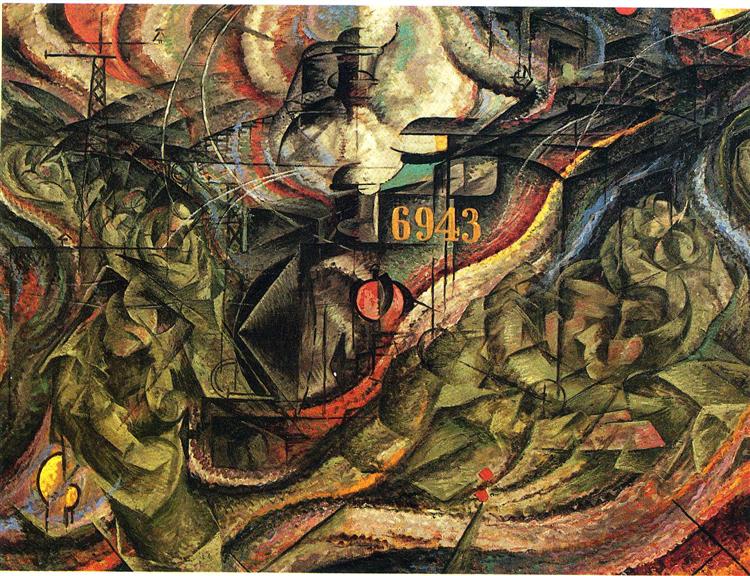

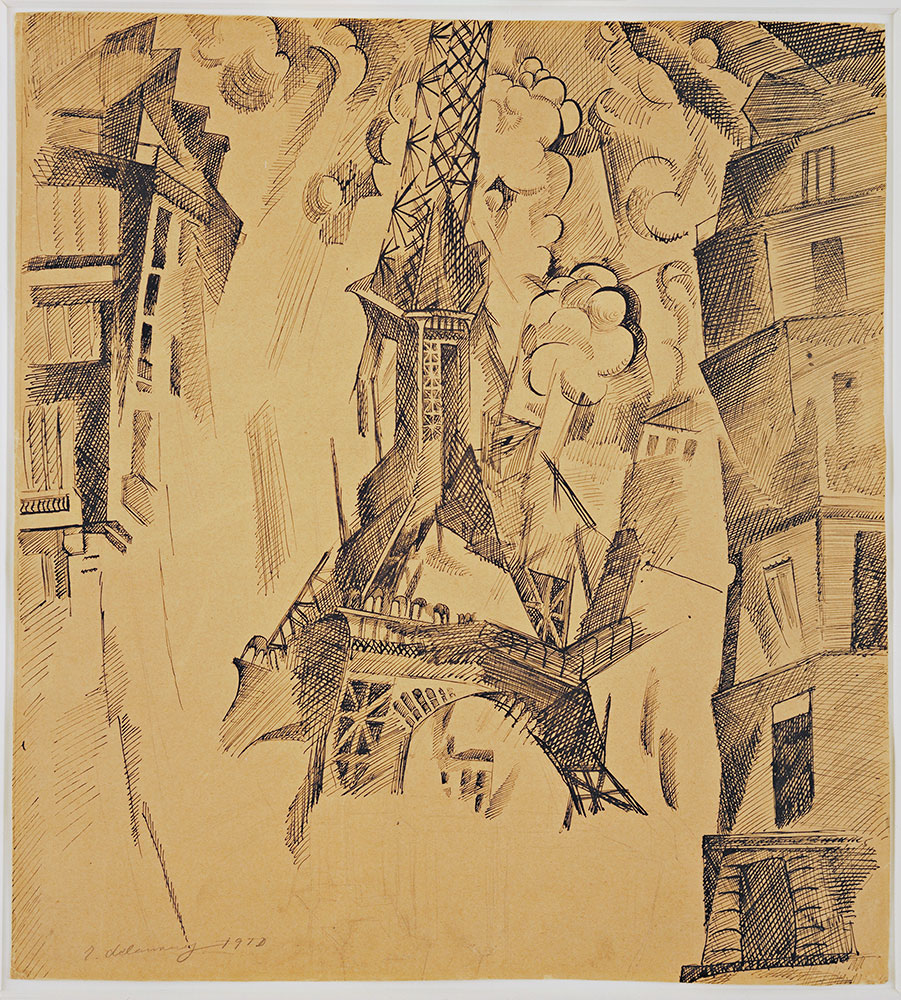

ALSO: Curie is awarded a second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry — for her discovery of the elements of radium and polonium; she was the first person to win or share two Nobel Prizes. Following experiments with Geiger and Marsden, Rutherford is the first to determine that a very small charged nucleus [in 1911, he called it a charge concentration, and in 1912 a nucleus], containing much of an atom’s mass, is orbited by low-mass electrons. Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (shown above) and a team of four become the first people to reach the South Pole. The reign of England’s George V begins. The Kaiser’s Hamburg Speech asserts Germany’s “place in the sun.” First appearance of newsreels. Revolution in Central China, Sun Yat-sen elected president; Chiang Kai-shek becomes military adviser. Wharton’s Ethan Frome, Chesterton’s The Innocence of Father Brown (in book form), and The Ballad of the White Horse (an influence on Robert E. Howard), Allain and Souvestre’s Fantômas, Conrad’s Under Western Eyes. Jarry’s posthumously published Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien hailed by Apollinaire as “the most important publication of 1911.”* Kafka begins writing (never-completed) Amerika. Eliot’s “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” expresses a New England propriety struggling with a withering irony. Braque’s Man with a Guitar.

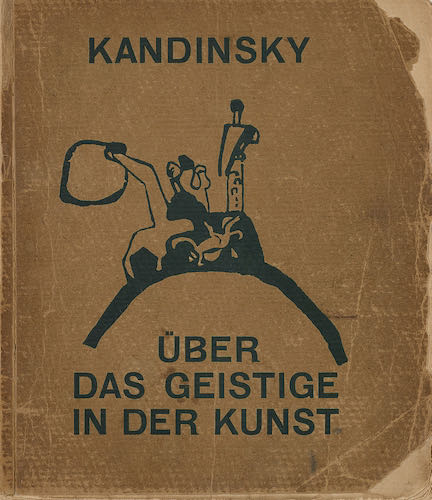

Kandinsky’s 1911/1912 book Über das Geistige in der Kunst (translated 1914 as Concerning the Spiritual in Art) sparked widespread interest in abstraction in the years leading up to World War I. On the cover and in ten woodcuts, Kandinsky illustrated his ideas by reducing complex scenes of spiritual battle and redemption to simplified designs of lines and shapes. For Kandinsky, abstraction was a weapon for transforming what he perceived to be a corrupt, materialist society. It lists several scientists whose work the artist finds inspiring; the late-19th century German astrophysicist and psychical researcher J.C.F. Zöllner, who helped popularize the concept of the Fourth Dimension, heads the list. Kandinsky suggests that Apollinaire’s earlier remarks about the Fourth Dimension are also likely inspired by Zöllner. (Zöllner had conducted dubious experiments in the late 1870s that seemed, he claimed, to verify occultists’ claims about a transcendental fourth dimensions.) From Theosophy, Kandinsky derives his concept that vibration is the formative agent behind all material shapes, which are but the manifestations of life concealed by matter. “Words, musical tones, and colors possess the psychical power of calling forth soul vibrations… ultimately bringing about the attainment of knowledge.”

PS: The Guggenhiem’s reverse-order retrospective show Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle closes in September. A must-see!

* Speaking of Apollinaire, his 1911 lecture on modern painting, which eventually becomes three chapters of his 1913 book Les peintres cubistes, compares the new painters to the late-19th century geometers for whom the three dimensions of Euclid’s geometry had become insufficient. The fourth dimension, he writes, “represents the immensity of space eternalizing itself in all directions at any given moment. It is space itself, the dimension of the infinite; the fourth dimension endows objects with plasticity.” That is to say, those visionaries able to see from the perspective of the fourth dimension perceive our world in a far-out, “infinite” way and — like primitive artists who paint and sculpt what they think rather than what they literally see — depict it as such.

Superconsciousness and Ways to Achieve It (1911) — M.V. Lodyzhenski — occult book that helped influence Russian Futurism.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin