RADIUM AGE: 1909

By:

June 18, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the years 1908–1909 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Oughts (1904–1913).

If we were to divide the Radium Age into quarters, 1909 would be the first year of its second quarter (1909-1917). How might we characterize this sub-era? Something for me to think about.

Hugo Gernsback’s essays “Signaling to Mars” and “Television and the Telephot” appear in his magazine Modern Electrics in 1909.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1909.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1909, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: none!

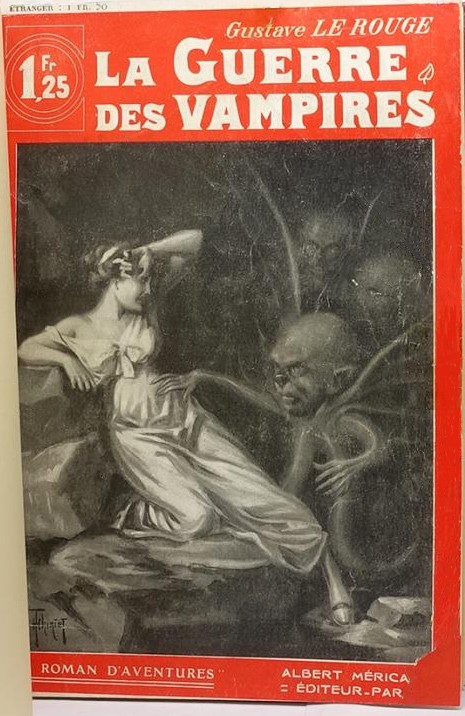

- Gustave Le Rouge’s Radium Age science fiction adventure La Guerre des Vampires (The Vampire War). In Le Prisonnier de la Planète Mars (see 1908), Robert Darvel discovered that Mars’s dull-witted humanoids are herded and harvested by the vampiric Erloor. (That is to say, it’s a kind of occult, hastily written mashup of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine and The First Men in the Moon.) Le Rouge has been credited with helping French sci-fi transition from its Vernean incorporation of science to a Wellsian imaginative fictionalization of science. In the feuilleton installments that make up this sequel, Darvel’s comrades back on Earth — including several brilliant inventors, the lovely millionairess Miss Teramond, and an avant-garde chef (!) — work feverishly in their Tunisian laboratory to communicate with Darvel. Their blind servant, Zarouk, can perceive “obscure radiations of the electromagnetic spectrum,” which will come in handy when invisible creatures follow Darvel back to Earth, kidnap Miss Teramond, and threaten to prey on all humankind. We discover that the Erloor are controlled by invisible, blood-drinking octopus-bat creatures, which inhabit a kind of massive Habitrail. Moreover, these Vampires are themselves preyed upon by a mysterious, psychic, volcano-dwelling entity. What can it be?

- Kate Douglas Smith Wiggin’s Susanna and Sue. Wiggin was an American educator, author and composer. She wrote children’s stories, most notably the classic children’s novel Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. In this one, Susanna’s husband’s desire to join the Shakers — an agrarian utopian cult — forces her to grapple with an impossible dilemma: how to keep her family intact in a group which does not recognize familial bonds. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops (1909). Written as a riposte to H.G. Wells’s 1899 technocratic utopia When the Sleeper Wakes, in which Londoners live in a multi-tiered underground society, connected by a vast rail network, Forster’s short novella The Machine Stops takes place in a future civilization in which the outdoors is all but uninhabited. A “Machine” supplies each inhabitant of this global civilization with everything he or she might desire — to a degree where, at this point, few people ever leave their well-appointed apartments. Socialization and entertainment are entirely mediated via the Machine: yes, Forster helped predict the Internet. Who programs the Machine? It’s unclear. In fact, most people are programmed by the Machine. When one courageous individual, Kuno, briefly visits the outside world, he’s shunned by his own mother. Later, when the Machine begins to break down, the inhabitants of this utopian society are utterly helpless. Fun fact: This story was published between the author’s much more famous works A Room With A View and Howards End. Serialized here at HILOBROW and included in Voices from the Radium Age (MIT Press), a 2022 story collection edited by yours truly. See this excellent 2022 essay about “The Machine Stops” by Paul March-Russell.

- Garrett P. Serviss’s A Columbus of Space serialized January-June 1909 in All-Story; rev 1911) features a pioneering space flight, powered by nuclear energy derived from uranium, to Venus. Fun facts: Serviss wrote as the “Sun‘s Astronomer” for a column on astronomy in the New York Sun between 1876 and 1892. His Edison’s Conquest of Mars (serialized 1898 in the New York Evening Journal) was an unofficial sequel to Wells’s The War of the Worlds, in which Edison and the world’s most famous scientists head off a second Martian armada in a spaceship armed with a disintegrator ray (both invented by Edison). One of the first edisonades to be written for adults, and an early example of space opera.

- Edith Nesbit’s “The Five Senses.” Collected in Fear (1910). Involves a mysterious drug that transforms its victims. “Time, measureless, spread round. It seemed as though someone had stopped all the clocks in the world, as though he were not in time but in eternity. Only by the waxing and waning light he knew of the night and the day.” Reprinted in The Dreaming Sex: Early Tales of Scientific Imagination by Women.

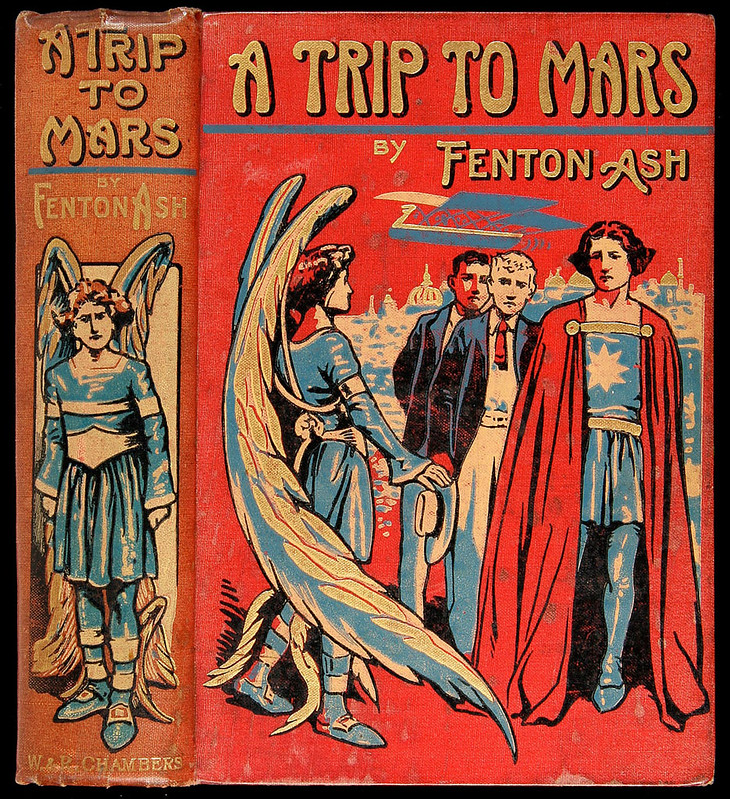

- Fenton Ash (Francis Henry Atkins)’s A Trip to Mars. Two boys who save the life of a visitor from Mars (who turns out to be the planet’s king) are abducted to that planet, where they have various adventures and help to suppress a revolt. Its most original feature is the spaceship used to transport the heroes, a compound of the organic and inorganic that qualifies as an early cyborg, according to Anatomy of Wonder.

- Irene Clyde’s Beatrice the Sixteenth — a feminist utopian novel about a time traveler who discovers a lost world (in another dimension?), which contains a postgender society. (The protagonist, Mary Hatherley, is an explorer and geographer, traveling through the desert somewhere in Asia Minor until a kick from a camel sends her into another plane of existence.) Set in a genderless land called Armeria where people with feminine characteristics form life unions. The novel has been described as a successful example of defamiliarization, in that it places the reader in a world initially without any firm indications of gender and this places strain on the reader’s attempt to apply existing social paradigms which require gender categorization. Some commentators draw attention to how the novel initially avoids the use of gendered pronouns, instead referring to characters as a “figure,” “person” or “personage,” yet as the novel progresses, gendered pronouns such as “she” are increasingly used and feminine characteristics are valued. Fun fact: The author, an English gender-fluid lawyer and writer, was born Thomas Baty. She also co-edited Urania; see 1916.

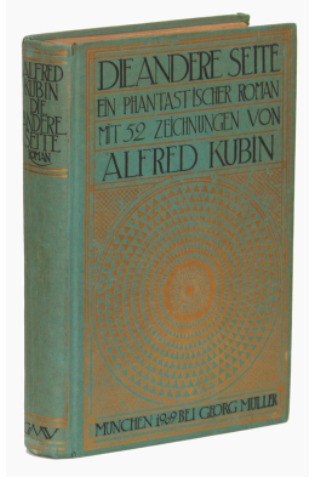

- Alfred Kubin’s Die andere seite (The Other Side). An Austrian artist’s apocalyptic extravanganza. The book tells of a “dream empire” in Asia, the creation of the narrator’s school-friend Claus Patera, and its decay and fall. Fantasy or sf?

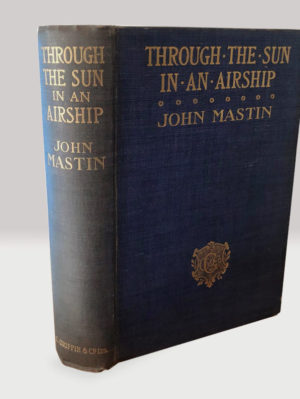

- John Mastin’s Through the Sun in an Airship. Proto-sf with a fin de siècle perspective on interplanetary voyaging across the solar system. The last descendant of the protagonist of Mastin’s The Stolen Planet (1906) tours a number of planets. Through his various narratives of fantasticated touring, Mastin tried to exploit the romance of science in stories which have an attractive (though thin) patina of verisimilitude (the solar system contains a number of conveniently undiscovered planets) and are told in the uplifting manner typical of too many UK boys’ books; they are permeated with religiosity, at times attempting a reconciliation of science and religion.

- Garrett P. Serviss’s “The Sky Pirate” (April-September 1909, in The Scrap Book) — a Verne-ian adventure about a master criminal with an air-yacht. Set in 1939-ish. Features the super-scientific exploits of the eponymous adventurer. Some years back, France and Great Britain fought each other in a war in which aeros had significant battles. Even when badly damaged, they generally sink slowly through the air rather than crash.

- Hilaire Belloc’s A Change in the Cabinet. Part of Belloc’s near-future assault on Edwardian politics; see 1908 for Mr Clutterbuck’s Election. This one, set in 1915, focuses on evolution and the discovery of “Caryll’s Ganglia,” whose presence in the human brain conclusively differentiates us from baboons.

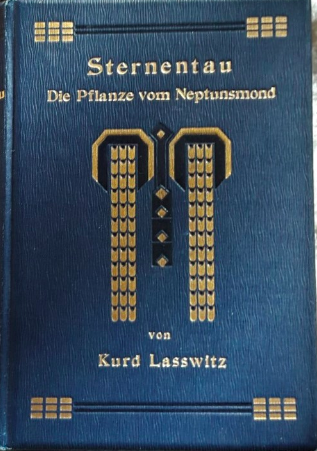

- Kurd Laßwitz’s Sternentau. Die Pflanze vom Neptunmond. Lasswitz was the first major proto-sf writer in German. The stories collected here explore technological and scientific advances; alas, they’re not very fun to read as stories.

- M.P. Shiel’s The Isle of Lies. Romance set (at first) on an island, combining themes of mad scientist, the creation of a superman and the conflict of scholarship and romantic love. Hannibal Lepsius is sired by his father to live a monastic and scholarly life and learn to decipher an ancient stone’s writings. All is well until a boat arrives — with women on board. The action then moves to Paris, where the escaped superman is putting his great and terrible plans into action. “A tale of the power of suggestion written before the word ‘suggestion’ was in everyone’s mouth, as now…” – Shiel (quoted in Locke, A Spectrum of Fantasy). I’ve just recently read this for the first time, and it’s very enjoyable.

NOTES: Richard Leahy’s essay “Superintelligence and Mental Anxiety from Mary Shelley to Ted Chiang” doesn’t mention The Isle of Lies, but it’s helpful to our reading in suggesting that Frankenstein “established… the anxieties revolving around intelligence as an ongoing and ever-evolving sf trope,” and “anticipate[d] the trope of emotionally alien superintelligences…” Superintelligences in sf ever since would “experience social alienation due to the incompatibility between their heightened cognitive intelligence and their emotional understanding.” Language is often a problem for these supergeniuses, who discover “the inadequacy of a structure of symbols intended to replicate and represent reality — a very Saussurean idea.” He suggests that sf supergeniuses possess “the ability to deconstruct reality in a semiotic sense… They are able to perceive the Barthesian structure of myth, and pick apart signs and the ideas they signify to the extent where language is unsettled, thus causing a disturbed relationship with their own self due to the alienation and isolation caused by existing within a system that they can see through.” (They have the ability to “see through matrixes of meaning and social construction, and understand the ideal Forms of reality.” He notes that Chiang’s supergenius is “able to perceive influence from all angles;” he quotes that character as saying that “lines of force twist and elongate between people, objects, institutions, ideas. The individuals are tragically like marionettes, independently animate but bound by a web they choose not to see…”) And Shelley’s “soulless” creature was perhaps the first in sf to suggest “the lack of empathy and detached nature of superintelligences,” “the cold harshness of absolute intelligence,” “a parallel between heightened intelligence and decreased moral empathy due to a hyper-awareness of self” [not sure I agree with this part]. We find in subsequent superminds “a deep anxiety rooted in isolation and alienation caused by enhanced self-awareness.”

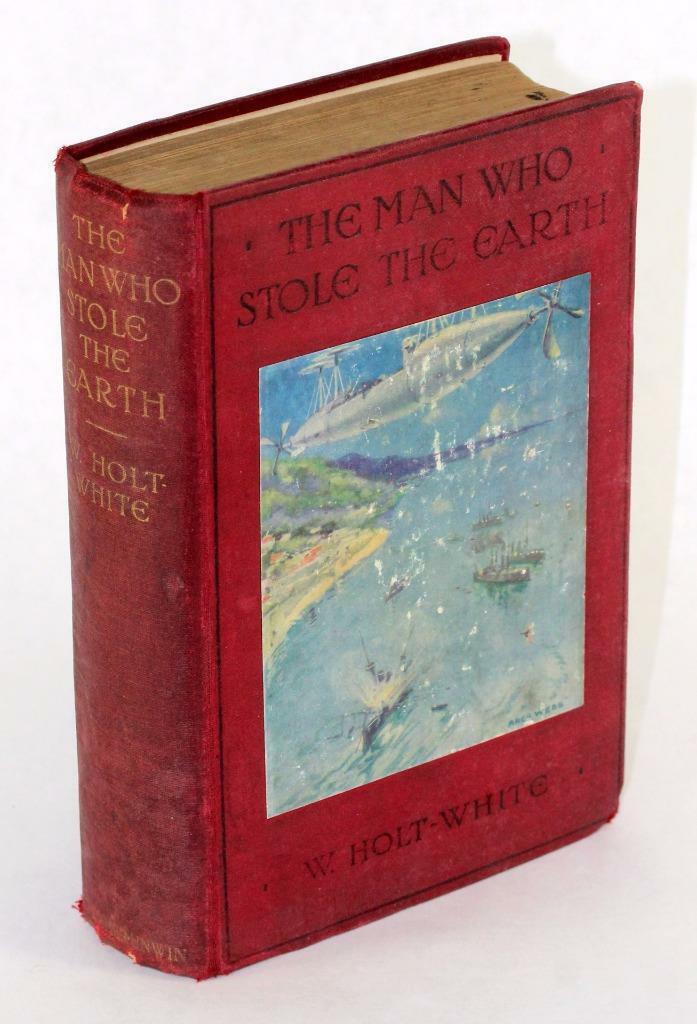

- W. Holt-White’s The Man Who Stole the Earth. Begins as a Ruritanian potpourri of politics and romance. A love-lorn inventor bombs most of Europe into submission in the course of his campaign to gain the hand of the daughter of the King of Balkania, forcing the world into a state of peace.

- Jacques Futrelle’s The Diamond Master (1909; exp as coll with “The Haunted Bell” [19 December 1908-January 1909 Saturday Evening Post] circa 1912) revolves melodramatically around the invention of the artificial manufacture of diamonds, and the inventor’s plan to capitalize on this by inviting established diamond magnates to pay a huge sum to suppress this invention rather than see their market flooded with cheap but perfect diamonds. The added novella is a partly rationalized supernatural tale involving Futrelle’s popular character Professor Augustus S F X Van Dusen, aka the Thinking Machine.

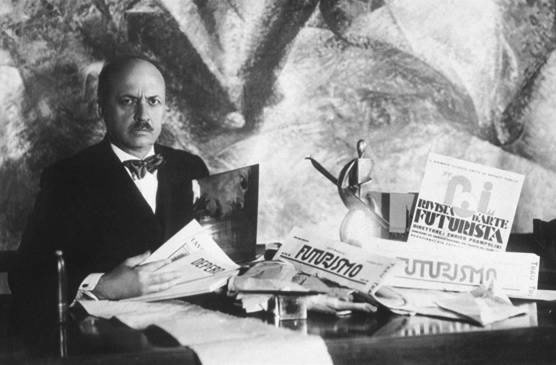

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Mafarka il futurista (trans. 1998 as Mafarka the Futurist: An African Novel). A chaotic tale of rape, pillage, and battle set in North Africa. Describes the feats of a North African dictator who creates, through his masculine rapport with advanced technology, an edifice whose aeronautical principles forcefully adumbrate and in fact embody the future. “The whole work comprises a grim prolepsis of the Pax Aeronautica if Marinetti’s future idols had in fact managed to take over Europe for good.” — SFE. Apart from its misogyny, racism, and glorification of a cult of violence, the novel is remembered for its hero’s creation of a machine brought to life as a superman. Closer to a poem than a novel.

- Maurice Baring’s “Venus” — collected in Orpheus in Mayfair. About an inventor who begins to astral-travel. An occult story, really — but of sf interest because there’s supposedly a scientific explanation.

- Maurice Renard’s Le Voyage Immobile, suivi d’autres histoires singulières. The title story in this collection features an unsteerable craft, powered by antigravity and detrimental to its passengers.

- George Allan England’s serial “The House of Transmutation” (September-November 1909 The Scrap Book, often incorrectly given as “The House of Transformation”) is reminiscent of The Island of Dr Moreau.

- George Allan England’s Lost World serial “Beyond White Seas” (December 1909-May 1910 All-Story) is about immortality and rejuvenation — a recurring theme for England.

- Some of Charles M. Doughty’s poetry is of sf interest. The Cliffs features an airborne “Persanian” invasion of England, which is successfully repelled; the SFE calls it one the most arcane Future War tales ever told. Excerpt from The Cliffs published at HILOBROW in 2022. Also see 1912 for a note on The Clouds.

- R. Norman Grisewood’s Zarlah the Martian. Visual communication is established with an advanced civilization on Mars and a human spirit is scientifically transferred into the body of one of the Martian inhabitants. Both of whom remain happy in their new bodies, though the Earthman – now long-lived, in an advanced society with antigravity machines, and a beautiful Martian wife – seems to have had the better deal, according to the SFE.

- Robert Blatchford’s The Sorcery Shop: An Impossible Romance — socialist utopian novel indebted to Morris’s News from Nowhere. Work has become pleasurable, cities become gardens, love becomes free. The Lamarckian idea that man can be shaped for the better by his environment, and these positive changes then passed along from one generation to the next, is very much in evidence. A journalist, Blatchford founded The Clarion, a weekly newspaper, in order to convert England to Socialism. He is best remembered for an earlier utopia, Merrie England (1893).

- Capt. H.G. Bishop’s “On the Martian Way.” Notable as one of the earliest proto-sf stories to feature a future of routine commercial space travel; also for its use of radio, friendly Martians, “computing machines,” and electrical gravity-repelling screens.

- William Hope Hodgson’s The Ghost Pirates. A ship bearing a mysterious curse slips into a hinterland between parallel worlds, where it becomes vulnerable to assault by bestial creatures from the other universe. “One of the great weird novels.” – Barron (ed), Horror Literature. Bleiler notes that it is derivative of The Inheritors by Conrad and Hueffer.

- P.G. Wodehouse’s The Swoop. Wodehouse was responding to an upsurge in the popularity of the invasion genre: 1909 marked “the year of greatest suppuration” of the genre. William Le Queux’s The Invasion of 1910 had been serialized in the Daily Mail and was a best-seller, while Guy du Maurier’s play, An Englishman’s Home, which had opened on 27 January, was a theatrical sensation.

- Rudyard Kipling’s “The House Surgeon” — a psychic detective story in the vein of Blackwood’s John Silence stories. Explains a ghost in terms of psi powers. First published in Harper’s Magazine for September and October 1909 and collected in Actions and Reactions the same year

- William Le Queux’s The Unknown Tomorrow: How the Rich Fare at the Hands of the Poor (in 1909 as “The Red Rage,” as a book in 1910). Most of the author’s popular works were espionage thrillers in the vein of E Phillips Oppenheim and detective novels. This is a proto-sf story about a socialist revolution in England — marriage is abolished, the seven-hour working day is instituted. Mobs sack London and burn temples of high culture such as the British Museum and and the Bodleian Library.

- Godofredo Emerson Barnsley’s São Paulo no ano 2000, ou, Regeneração nacional — a Bellamy-ish proto-sf novel from Brazil.

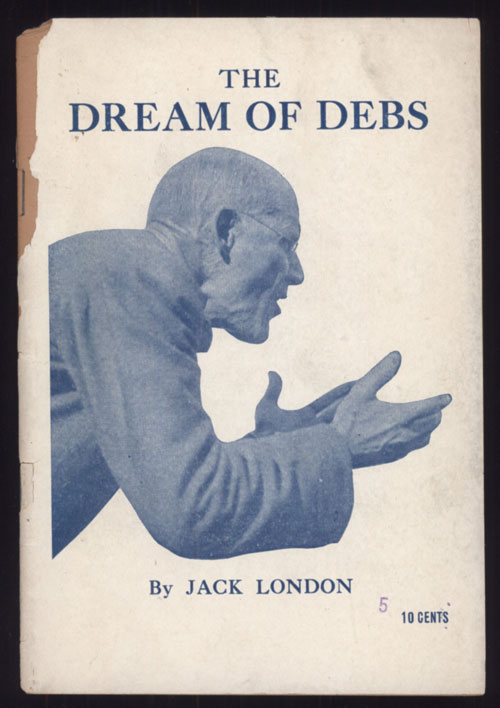

- Jack London’s “In The Dream of Debs” (January 1909 International Socialist Review; circa 1912 chap). A near-future general strike brings the capitalist class to its knees. Short story, first published in International Socialist Review, January 1909, later collected in The Strength of the Strong (1914). “… A fine science fiction story as well as revolutionary tract in which for once London used an orthodox Marxist analysis to draw a picture of the future — a future that is not merely a projection of tendencies already present in his day, but is instead the outcome of as-yet-invisible forces that are the dialectical antithesis of the ones determining the reader’s familiar existence,” writes Richard Gid Powers. “It is excellent science fiction that explores the social and human impact of a great scientific innovation, the development of proletarian class consciousness. As a work of propaganda it is one the socialist propagandists have never tired of reading, for it describes the future as the outcome of that very transformation of consciousness that is the goal of the revolutionary agitator.”

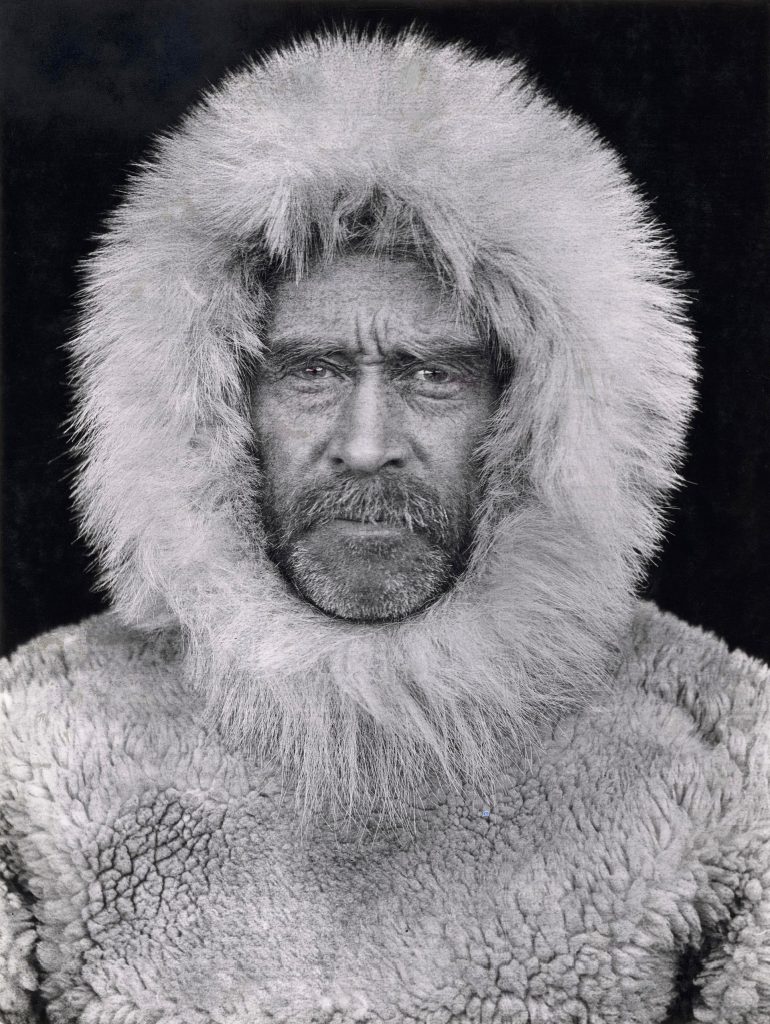

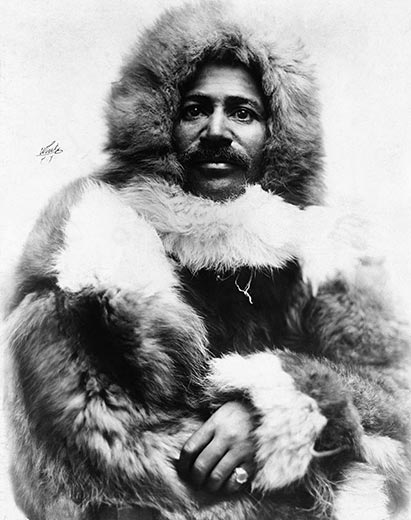

ALSO: Soddy’s The Interpretation of Radium; H.G. Wells would dedicate The World Set Free — in which he hypothesizes both atomic energy and atomic bombs — to Soddy’s book. Farman makes first 100-hour flight. Robert Peary, Matthew Henson, and four Inuit explorers come within a few miles of the North Pole. Apollinaire’s L’Enchanteur pourrissant; Pound’s Personae one of the first radical declarations of poetic modernism. Lloyd Wright’s Robie House. Gaston Leroux’s Le Fantôme de l’Opéra; P.G. Wodehouse’s Mike introduces his character Psmith. Influenced by Charles Hinton, P.D. Ouspensky (who’d become interested in Theosophy in 1907), publishes The Fourth Dimension; his 1915 novel Strange Life of Ivan Osokin would indirectly fictionalize the theory.

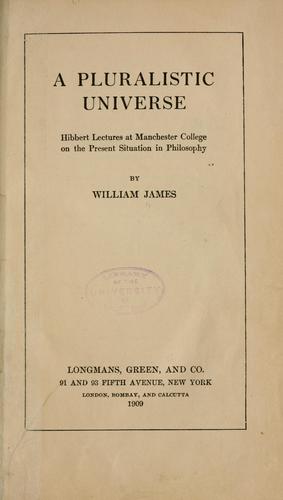

William James’ pamphlet A Pluralistic Universe defends the mystical and anti-pragmatic view that concepts distort rather than reveal reality. James passes from critical discussions of Josiah Royce’s idealism and the “vicious intellectualism” of Hegel to philosophers whose visions he admires: Gustav Fechner and Henri Bergson. He praises Fechner for holding that “the whole universe in its different spans and wave-lengths, exclusions and developments, is everywhere alive and conscious.” (Fechner’s philosophy is characterized by a clash between his metaphysical interests and his positivist proclivities. His metaphysical interests led him toward panpsychism: the doctrine that the universe is created and governed by mind or the soul; his positivist leanings led him to uphold an early version of verificationism and phenomenalism. Fechner insisted that there was no disparity between these tendencies, that the best scientific evidence supported the view that the universe is psychic.)

James employs Henri Bergson’s critique of “intellectualism” to argue that the “concrete pulses of experience appear pent in by no such definite limits as our conceptual substitutes are confined by. They run into one another continuously and seem to interpenetrate.” James concludes by embracing a position that he had more tentatively set forth in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902): that religious experiences “point with reasonable probability to the continuity of our consciousness with a wider spiritual environment from which the ordinary prudential man (who is the only man that scientific psychology, so called, takes cognizance of) is shut off.” Note that James was influenced by Bergson (as he writes in A Pluralistic Universe) “to renounce the intellectualist method and the current notion that logic is an adequate measure of what can or cannot be”. Bergson had induced him, he continued, “to give up logic, squarely and irrevocably” as a method, for he found that “reality, life, experience, concreteness, immediacy, use what word you will, exceeds our logic, overflows, and surrounds it.”

As the author of “Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo” (first appeared as a preface to a 1909 volume of his poems, then reprinted in Italian and French newspapers the same year; translated 1912 as “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism”), Filippo Marinetti is credited with founding the Futurism movement. His “Futurist Manifesto” argues for an epiphanic immolation in the technology of the new age, citing iconic instances of new machines like racing automobiles, or the machine-gun, whose role it is to break the world so the future can come through. This goal is narratized through an explosive, “cleansing” kinetic of speed: progress made manifest. The Manifesto anticipates any future war with glee. The supermen capable of glorying in the endless paroxysm of energy thus given bodily form will necessarily harry women and exalt those fellow supermen who grasp political power. (“We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.”) Futurism flourished primarily in Italy in the years before World War One. Marinetti himself would become a convinced Fascist.

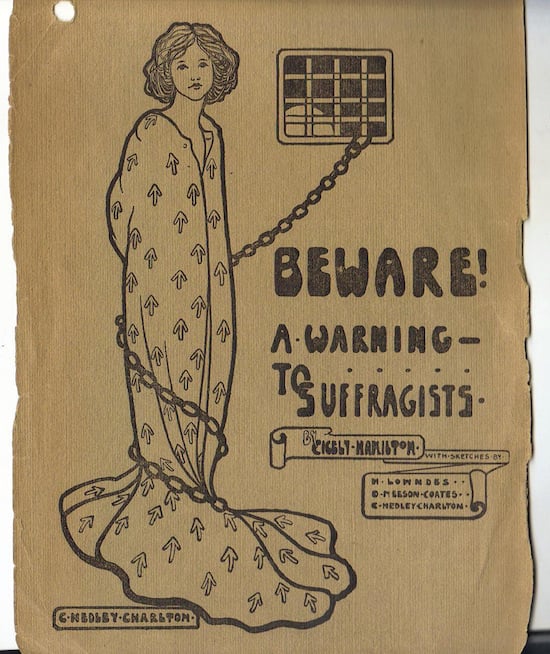

Read Beware! A Warning to Suffragists here.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin