RADIUM AGE: 1932

By:

November 27, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

In Time Machines, Ashley claims that 1932-1933 is phase three of a 25-year period of the sf pulp mags (i.e., from inception c. 1926 to 1950); during this brief phase David Lasser forced realism into sf (see note in 1931). “Realist” sf would rapidly permeate the field and take off with Campbell, ushering in sf’s so-called Golden Age.

Strange Tales and Astounding Stories cease publication in 1932.

The first of many “weird-menace” pulps — offshoots of the detective pulps; the victims (usually women) find themselves being hunted and tortured by sadistic villains — appears late in 1932: Dime Mystery.

Copyrighted works from 1932 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2028. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1932, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ATOMICS | EARTH-NORMAL (a state, amount, or value of something (as gravity or atmospheric pressure) that is typical of what is found on Earth) | GRAVITY DRIVE (a spaceship drive that uses any technology associated with gravity) | JUMP (a journey through hyperspace n.; any (nearly) instantaneous travel over a large distance; cf. jump) | LIGHT-SPEED (a unit of measure equal to the speed of light; cf. light) | MOON BASE | NEEDLE GUN | OUTWORLD (on or from another planet, esp. one remote from the homeworld or far from a solar system’s star) | SOMA (in Brave New World: a narcotic drug which produces euphoria and hallucination, distributed by the state in order to control the population by promoting content and social harmony) | SPACE COLONY | SPACEMAN | SPEEDER | SUPERPOWER | TELEPORTATION | TELESCREEN | VIEWPHONE | WARP (to travel through space by means of a space warp).

- Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932). Six hundred and thirty-two years A.F. (After Ford), a narcissistic culture of youthfulness, consumption, mood-altering drugs, and sexual promiscuity has become dominant throughout the World State. Fetuses are manipulated, and children conditioned, in such a manner as to produce an optimal ratio of labor to management; two of the story’s main characters, the “pneumatic” Lenina Crowne and Bernard Marx, work in London’s Directorate of Hatcheries and Conditioning. Bernard is troubled by the methods by which society is sustained; Lenina is content. While on vacation at a “Savage” (pre-Fordist) reservation in New Mexico, Bernard and Lenina discover John, a young man whose mother was from the World State; John sees everything in terms of Shakespearean characters, plots, and tropes. John makes attempts to intercede in the smooth functioning of the soulless “brave new world” he discovers; he is thwarted at every turn, though. Will he succeed in winning “the right to be unhappy”? Fun fact: One of the most famous science fiction novels of all time, Brave New World anticipates real-world developments in reproductive technology. The Modern Library ranked it fifth on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.

- Olaf Stapledon’s Last Men in London (1932). This is the story of Paul, a teacher telepathically possessed by a member of an evolved human species (the Last Men) living in the distant future, and one of Paul’s students: “Humpty,” a London teenager and “supernormal” in whom there is “some promise of a higher type.” As adolescents, the reader is led to believe, all “submerged supermen” like Humpty (whose nickname refers to his oversized cranium) are misfits: they don’t take themselves seriously, they don’t want to get ahead, they despise athletics, they’re puzzled and bored by religion and patriotism, they don’t regard sexuality as shameful, and they remain idealistic long after childhood. Humpty outlines a plan to found a new human species — one that will control the world and eliminate or domesticate the “subhuman hordes”; however, luckily for the rest of us, he succumbs to despair. Fun fact: Stapledon writes insightfully about homo superior — he’s credited with coining the term — in three of the four novels for which he’s remembered.

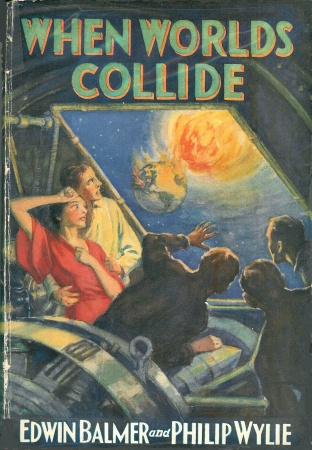

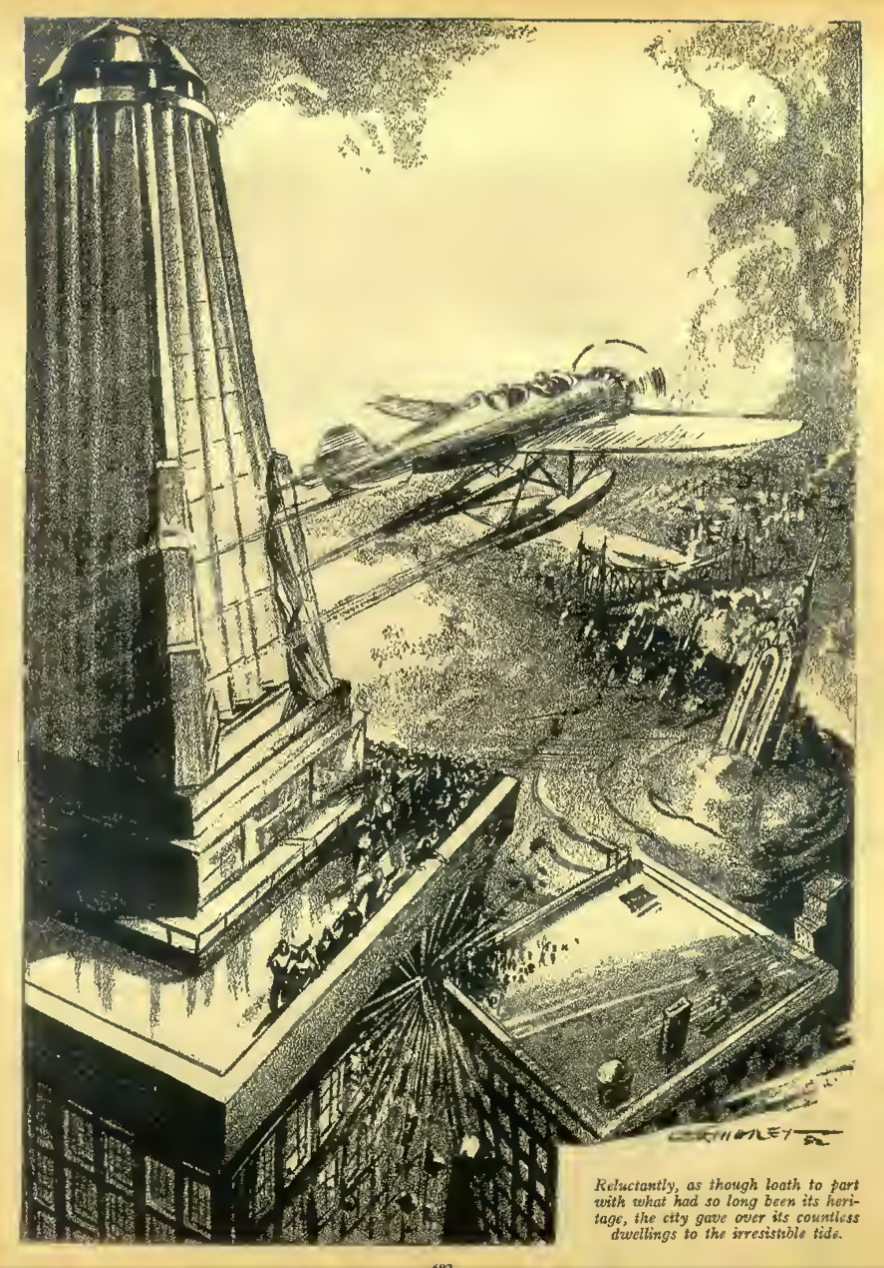

- Edwin Balmer and Philip Gordon Wylie’s When Worlds Collide (1932). Two rogue planets are entering the sun’s orbit! The League of the Last Days — an international band of 1,000 brilliant scientists, action heroes, and fertile women (I exaggerate, but not much) — hatch a desperate plan, and set about designing, constructing, and outfitting rocket-arks. We are treated to two terrifying apocalyptic scenes: One, when the rogue planets first pass by the Earth, triggering stupendous cataclysms; and the other, when worlds collide: “The very Earth bulged… It became plastic. It was drawn out egg-shaped. The cracks girdled the globe. A great section of the Earth itself lifted up and peeled away….” But it’s the post-apocalyptic scenes that are the most haunting: a deserted Chicago whose skyscrapers are knocked out of plumb; violent, half-naked mobs battling the National Guard in Pittsburgh; an army of hate-filled Midwesterners that nearly succeeds in wrecking the rocket-ship project. Sequel: After Worlds Collide (1934). Fun facts: The book influenced the strip Flash Gordon, while Siegel & Shuster lifted key ideas from both When Worlds Collide and Wylie’s earlier SF novel, Gladiator when they created Superman. George Pal’s 1951 movie adaptation of Worlds is a sci-fi classic.

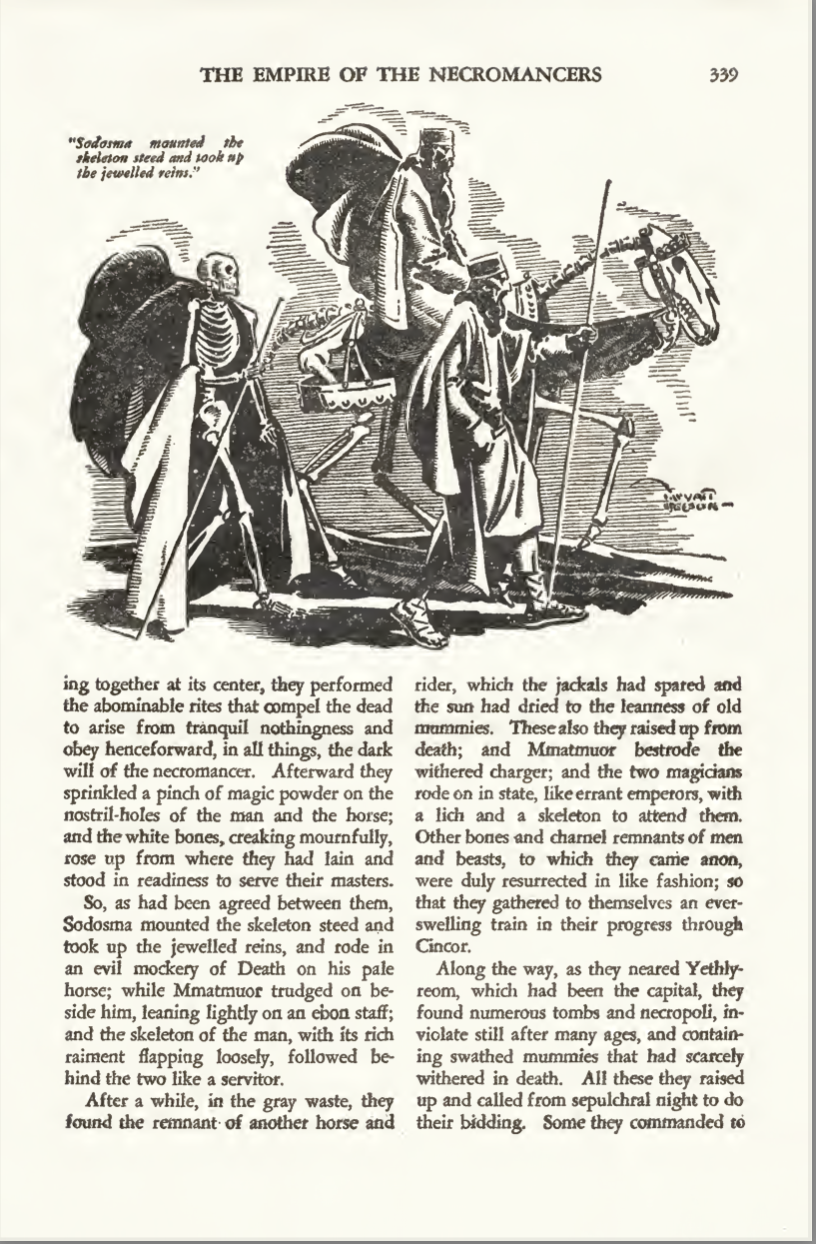

- Clark Ashton Smith’s Zothique (1932-1953). In sixteen stories, not to mention a verse play (!), all written in gorgeous, ornate prose, and all published in the pulp magazine Weird Tales, Smith depicts the dark goings-on of Zothique, a continent where the elites live in perfumed decadence, and lost kingdoms litter the deserts. Most of the story’s main characters are necromancers: indeed, the first-published Zothique story is titled “Empire of the Necromancers” (September 1932). Other memorable titles include “The Isle of the Torturers” (March 1933), “The Dark Eidolon” (January 1935), “The Tomb Spawn” (May 1934), and the Robert E. Howard-esque “The Black Abbot of Puthuum” (March 1936). So is this fantasy, as opposed to science fiction? It’s both. The Zothique stories are set in the far future, when Earth’s sun glows a dim red; Zothique — comprising what once were Asia Minor, Arabia, Persia, India, and parts of northern and eastern Africa — is the only continent extant. In fact, Smith is credited with having pioneered the Dying Earth genre of science fiction. Fun fact: Along with H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith made the years 1933-37 a Golden Age for Weird Tales.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s first collection, The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies (coll 1932 chap [large pages; reprints are over 100 pages long]), in which at least three tales from various venues are presented together, without comment.

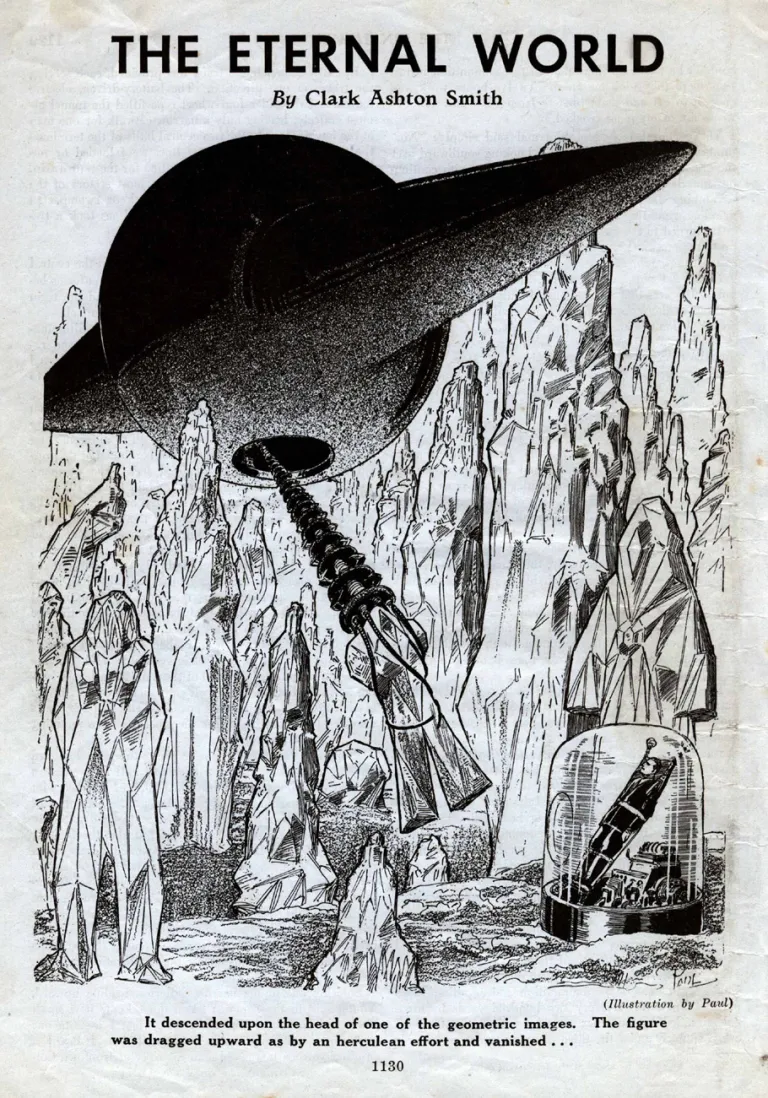

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Eternal World” (Wonder Stories, March 1932). A man invents a mechanism, utilizing a force which can project him laterally in universal time, thus achieving instantaneous space-transit. The force projects him beyond time and space, as we know them, into a universe with different properties, into a sort of eternity, peopled with strange, frozen figures, where he and his machine are unable to function, as if they were caught in a block of ice, though he maintains a sort of consciousness, such as might characterize the unmoving things about him. Into this timelessness, there come invading entities, who, by means of some sort of super-magnetic force, are able to move and live, albeit sluggishly. They take the time-explorer in his mechanism, and certain of the timeless ones, back to their own world, intending to enslave them and release the dynamic power of the eternal beings in a war against rival peoples. Evidently they have taken the explorer for one of the timeless things. In this world, subject to ordinary time-space conditions, the statue-like entities become instantly alive and tremendously active and defy all control of their captors.

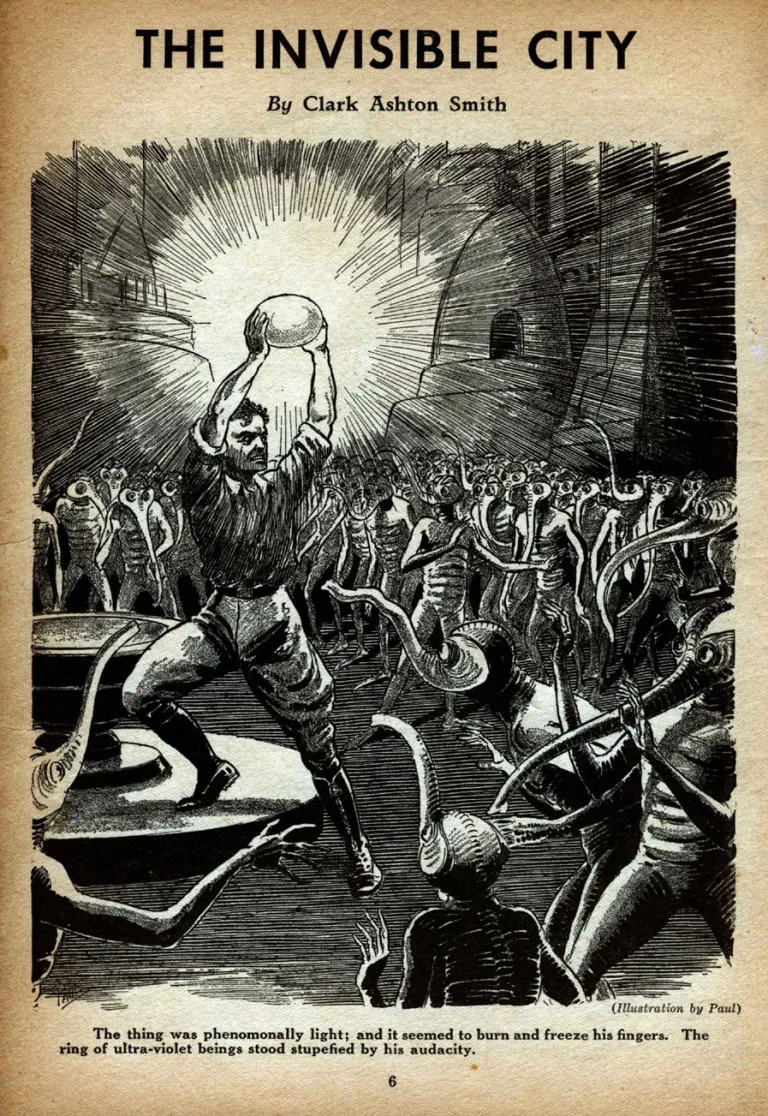

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Invisible City” (Wonder Stories, June 1932). Two explorers, wandering in the Gobi desert, lost, and searching for water, come to a series of strange, regular-shapen pits in the desert floor. Examining these, they find to their amazement that the pits are covered with an invisible, solid substance, that they are walking among unseen walls, on unseen pavements, in what appears to be a maze of buildings wrought of an ice-cold substance absolutely permeable to light. In some of the pits they see the apparently floating bodies of strange creatures, which they take to be mummies. One of the two men falls down a flight of steps, drops his rifle, and is attacked by an unseen monster, the minotaur of this strange labyrinth….

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Flight Into Super-Time” (Wonder Stories, August 1932). Eccentric millionaire Domitian Malgraff and his Chinese servant Li Wong head off in a time machine, first to adventure into the future, but if that fails to hold there interest—says Malgraff in a letter to his ex-fiancée—there is always the past.

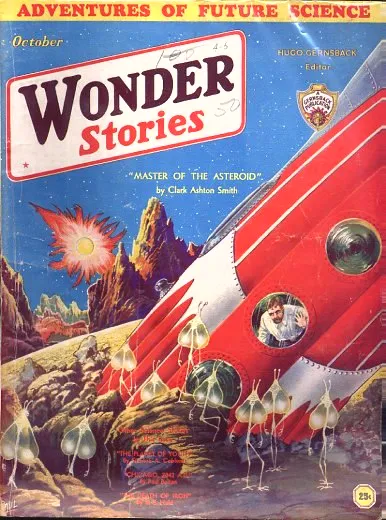

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Master of the Asteroid” (Wonder Stories, October 1932). “One of the cliques consisted of three men, Roger Colt, Phil Gershom and Edmond Beverly. These three, through banding together in a curious fashion, became intolerably antisocial toward all the others. It would seem that they must have gone close to the borderline of insanity, and were subject to actual delusions. At any rate, they conceived the idea that Mars, with its fifteen Earthmen, was entirely too crowded. Voicing this idea in a most offensive and belligerent manner, they also began to hint their intention of faring even further afield in space.”

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Dimension of Chance” (Wonder Stories, November 1932). “Far off, through the inconceivably clear air, on the enormously extended horizon, he could see the faint notching of the California mountains. Then, as the planes hurtled on, it seemed to him that a vague, misty blur, such as might appear in sun-dazzled eyes, had suddenly developed in mid-air beyond the Japanese. The blur baffled him, like an atmospheric blind spot, having neither form nor hue nor delimitable outlines. But it seemed to enlarge rapidly and to blot out the map-like scene beyond in an inexplicable manner.”

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Planet of the Dead” (Weird Tales, March 1932). An amateur astronomer is studying a certain remote, obscure star, which fascinates him greatly, when he falls into a cataleptic condition. In this state, which lasts for hours, he undergoes a psychic experience which seems to cover years. He finds himself in a world of dim, tremendous antiquity, lit by an aging sun. When a catastrophe overtakes this sun, he returns to mortal life, and finds that the star he was studying has vanished.

- J.B. Priestley’s Dangerous Corner. A play about time — rewinding it, undoing mistakes.

- Jack Williamson’s “The Moon Era.” Asimov found this long, fervently Merritt-esque story imaginative and moving. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- I.M. Stephens’s (Inga Marie Stephens Pratt) with Fletcher Pratt’s “A Voice Across the Years” in Amazing Stories Quarterly, Winter 1932 (later expanded as Alien Planet). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Aelfrida Tillyard’s The Approaching Storm. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women. A rare and unusual work of speculative fiction. Published seven years before the start of the Second World War, this dystopian novel tells of a “stricken England” in the aftermath of a period of international conflict, defeated and under the control of a totalitarian “Red Republic”. The story follows the two child protagonists who are taken in by an “old country squire” who describes the country as it was and how it had come to be. The blurb at the front of the book promises a “provoking and sensational” climax.

- Hazel Heald’s “The Man of Stone”, in Wonder Stories, October 1932. Heald was a pulp fiction writer, who lived in Somerville, Massachusetts. She is perhaps best known for collaborating with H. P. Lovecraft. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

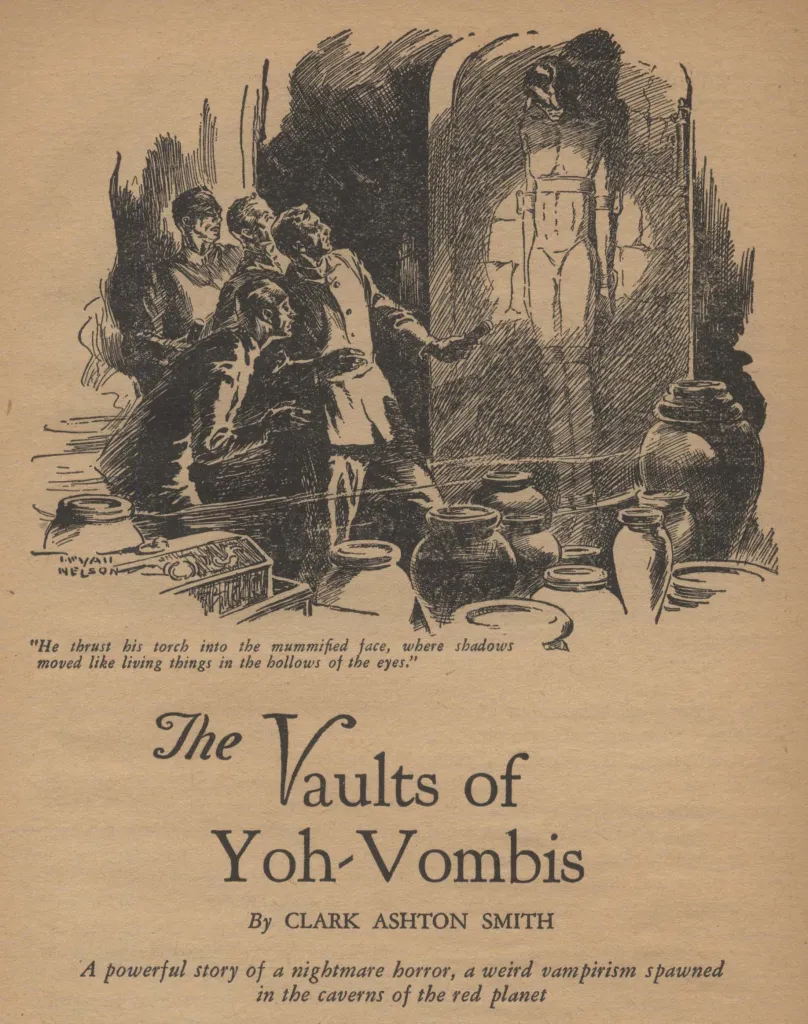

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Vaults of Voh-Vombis” (Weird Tales, May 1932). Some human explorers in a deserted ancient city on Mars are driven to take shelter in subterranean vaults by a strange, crawling, mat-like monstrosity called the vortlup. The vaults are evidently of mausolean nature, and contain the mummies of an ancient Martian race, some of which lack the upper portion of the head. The explorers become separated in the dark, winding passages, and one is lost from the others. They hear a muffled cry at some distance, followed by silence; and going in the direction of the cry with their flashlights, meet a terrible sight — the body of their comrade which still walks erect, with a great black, slug-like creature attached to the half-eaten head. The thing is controlling the corpse which passes its friends, enters another catacomb, and removes a heavy boulder from the mouth of a deeper vault….

- Julian Huxley’s The Captive Shrew and Other Poems of a Biologist. See “To a Dancer” and “Cosmic Death.” Aldous Huxley’s brother.

- J.B Morton’s poem 1933 And Still Going Wrong is of sf interest. The collection assembles verse satires about the then very Near Future, satire and nonsense being the intimately intertwined primary modes of his poetry. Composed in the rancorously anti-“progress” anti-Modernist fashion of his mentor Hilaire Belloc.

- S. Fowler Wright’s vivid early short fiction was assembled in The New Gods Lead, which groups seven vitriolic dystopian stories under the heading “Where the New Gods Lead” (the new gods in question being Comfort and Cowardice). Set in nightmarish future where scientism has made life frightful. These include a notable fantasy of immortality, “The Rat” (March 1929 Weird Tales), a trilogy of parables about the taking over of human prerogatives by machines, “Automata” (September 1929 Weird Tales), and two polemics against Wright’s pet hates, birth control and the motor car, “P.N. 40” (June 1929 Red Book Magazine as “Love in the Year 93 E.E.”) and a new story, “Justice.”

- Jack Williamson’s “Wolves of Darkness.” About an invasion by beings from another dimension. Ashley’s Time Machines says this story is memorable, about fourth-dimensional werewolves. Not an early version of Williamson’s novel Darker Than You Think. Clovis McLauren, a medical student studying in New York, receives a telegram from his father asking him to come to the ranch in the Texas Panhandle. His father is a physicist conducting some type of experiments on the ranch that involve light. When he arrives at the ranch he is attacked by wolves. Bullets don’t seem to hurt the animals. Running with them is a beautiful girl wearing only a thin silk shift. She is Stella, the daughter of the man assisting Clovis’s father. Like everyone else alive at the ranch, she has been possessed by some entity. Dr. McLauren’s experiments opened a doorway to another dimension, and something evil has come through!

- Francis Flagg’s “The Seeds of the Toc-Toc Birds” (Astounding, January 1932). A man named Talbot is doing geological work on an old mine when his Mexican helper, Manuel, draws his attention to a strange looking bird with metallic feathers. Later he hears strange noises coming from the old mine, but urgent business takes him away before he can explore them. Later the town of Oracle, near the mine, is overtaken by strange jungle plants that spring up almost immediately. These plants are seeded by strange black globes that drop the seeds. After oracle, the weird invasion moves on to Tucson. Eventually the army is called in to deal with the strange plants and the odd-looking birds and globes. The cause of the invading birds and seeds becomes known when Milton Baxter, a student of Professor Reubens, comes forward to explain to Congress what he knows. Reubens had witnessed the professor’s invention of a machine that could look into matter, into the multiverse of worlds that exist inside a single grain of sand. There he discovers the race of the Toc-Toc Birds and their advanced mechanical society. The professor works with the birds to bridge the two worlds. The Professor has since disappeared.

- Lao She’s Cat Country (simplified Chinese: 猫城记; traditional Chinese: 貓城記; pinyin: Māochéngjì, also translated as City of Cats). Serialized 1932, as a book 1933. See – chapter in Isaacson. Allegory for Chinese society set on a Martian landscape; an attempt to come to terms with Western epistemology; a dystopian Martian travelogue. The unnamed first-person narrator’s spaceship crash-lands on Mars. His companion perishes in the crash, and he is stranded alone. He soon meets the planet’s inhabitants, who have the faces of cats but otherwise appear human, and is captured by some of these cats and meets the leader of the group, called Scorpion, a landlord who owns a plantation of “reverie leaves,” an addictive drug that is used by all cats. The narrator is employed by Scorpion to guard his reverie leaves and eventually learns Felinese and gets acquainted with the country and its culture, guided by Scorpion and his son Young Scorpion. In China, this novel represented a resuscitation of sf after two decades of near total silence in the genre. A bleak take on Chinese prospects inspired by Wells’s The First Man in the Moon. Lao She declared his attempt at satire a failure.

- Howard Fast’s “Wrath of the Purple” (Amazing, October 1932). About a blob whose growth is unstoppable (for a while). Though now known for his historical works (particularly Spartacus), Fast broke into print in Amazing, with this story. He would not actively produce sf until the later 1950s.

- Eando Binder’s “The First Martian” (Amazing, October 1932). Earl and Otto Binder’s first story; a first contact story

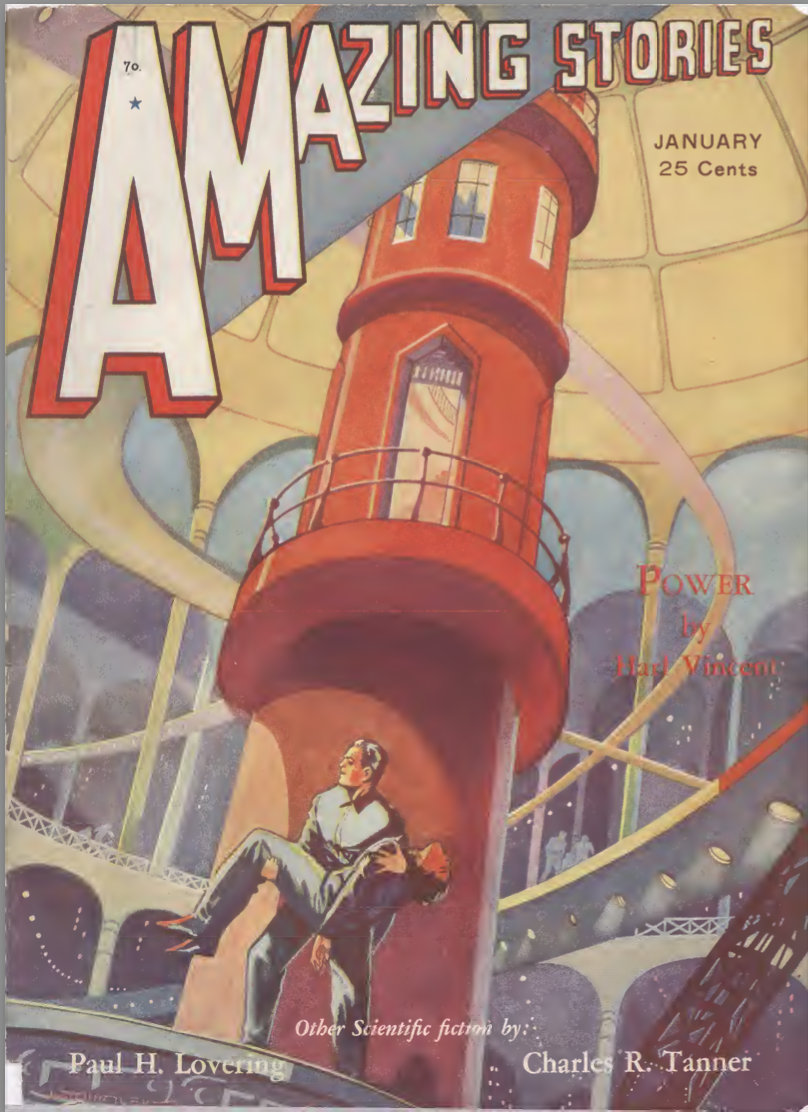

- Charles R. Tanner’s “Tumithak of the Corridors” (January 1932 Amazing). Survivors of an alien invasion of earth. Tanner is best known for his series featuring Tumithak, which began with “Tumithak of the Corridors.” Set in the fifty-third century, two millennia after Earth has been invaded by the shelks from Venus and mankind has been driven underground into a maze of deep tunnels. In that period humans have forgotten most of their previous advanced science. Tumithak, a young man, determines to venture to the surface and kill a shelk, and en route discovers other forms of humans and societies that have emerged. In “Tumithak in Shawm” (June 1933 Amazing), generally a better story, Tumithak leads a party of warriors back to the surface to defeat the shelks. There are other post-Radium Age Tumithak stories, too. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- P. Schuyler Miller and Walter Dennis’s “The Duel on the Asteroid.” Sequel to “The Red Spot of Jupiter.”

- Francis Flagg’s “After Armageddon” (Wonder Stories, September 1932) is a post-apocalyptic tale narrated by a man who remembers the old days to his young apprentice, Bilembo. The French invade America with a weapon of mass destruction that looks like explosive and poisonous fog. The fogballs as they are known don’t dissipate but last for decades, rolling about destroying life and property. The narrator is a rich man with servants and multiple homes in L. A. and the country. When the killer fogs come he flees with his family and the help in a flying car. Slowly technology fails and the survivors revert to more savage ways. The narrator’s butler Williams changes from servant to master as he leads their small band through dangers. He solves their first crisis, the lack of women, by instituting polygamy. Williams takes the band back to the Pacific coast before dying, where the narrator assumes his role as head priest.

- Henrik Dahl Juve’s “In Martian Depths” (Wonder Stories, September 1932). A hostile and unfriendly Mars — more “realistic” than space opera had tended to be.

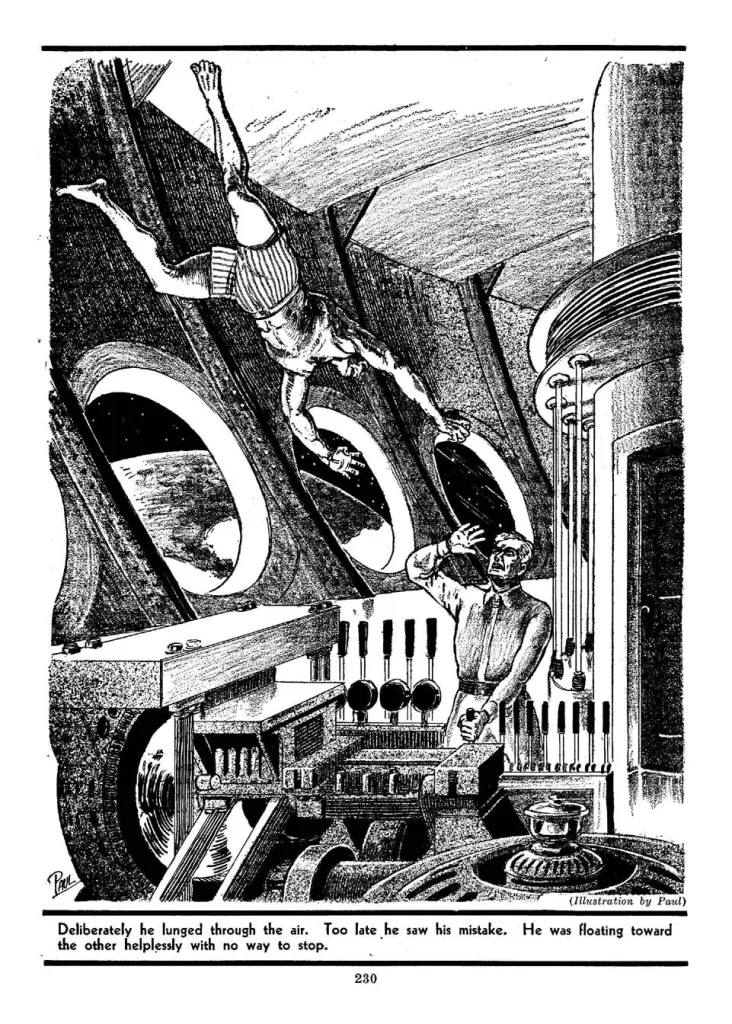

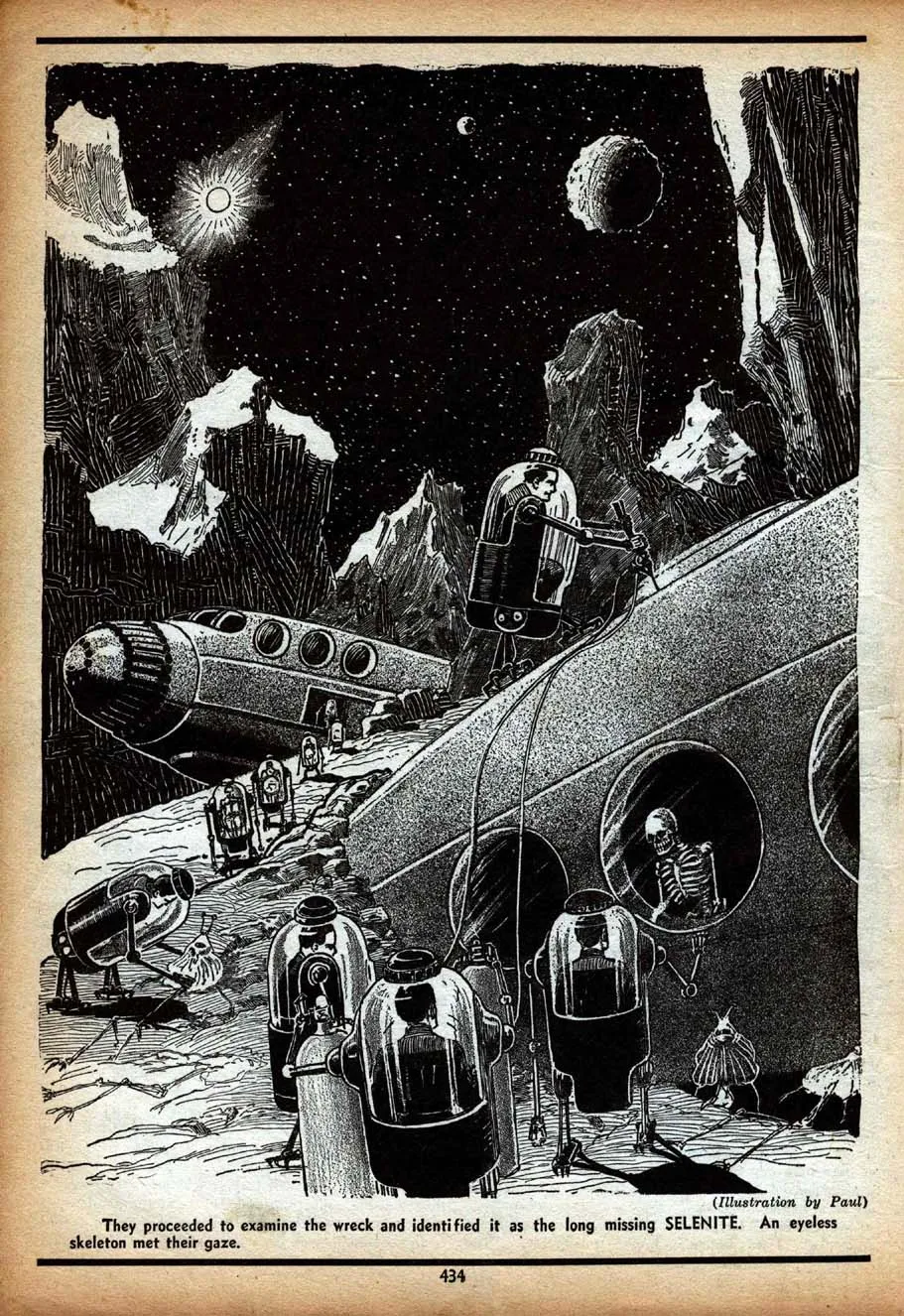

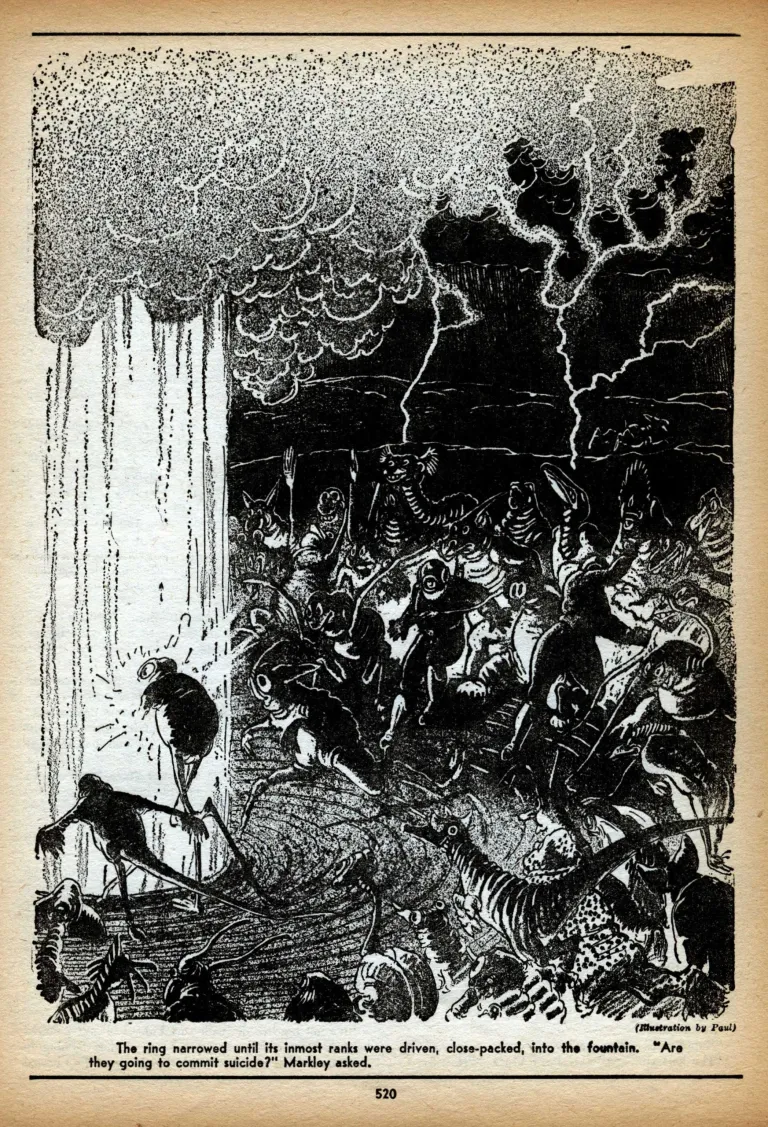

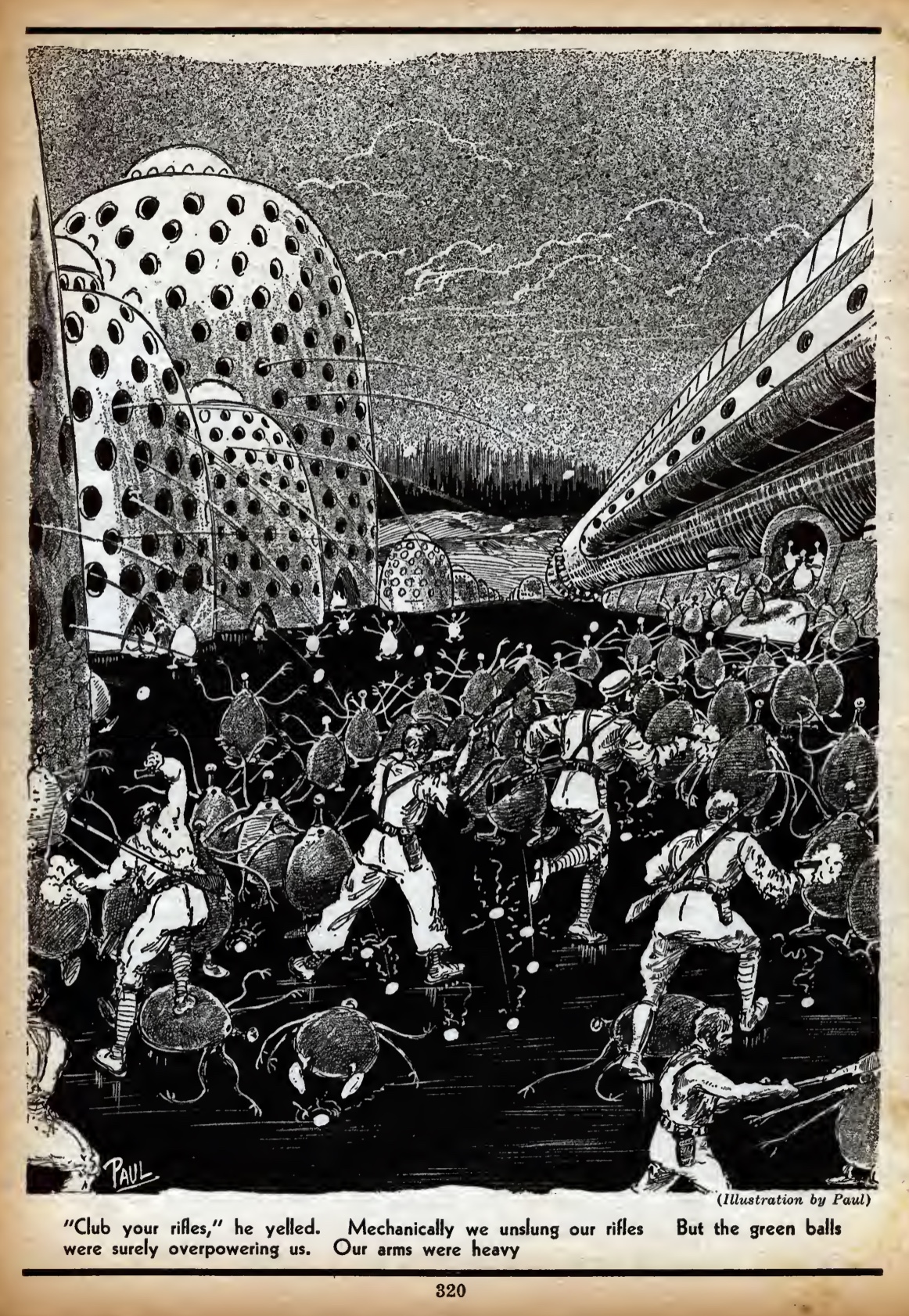

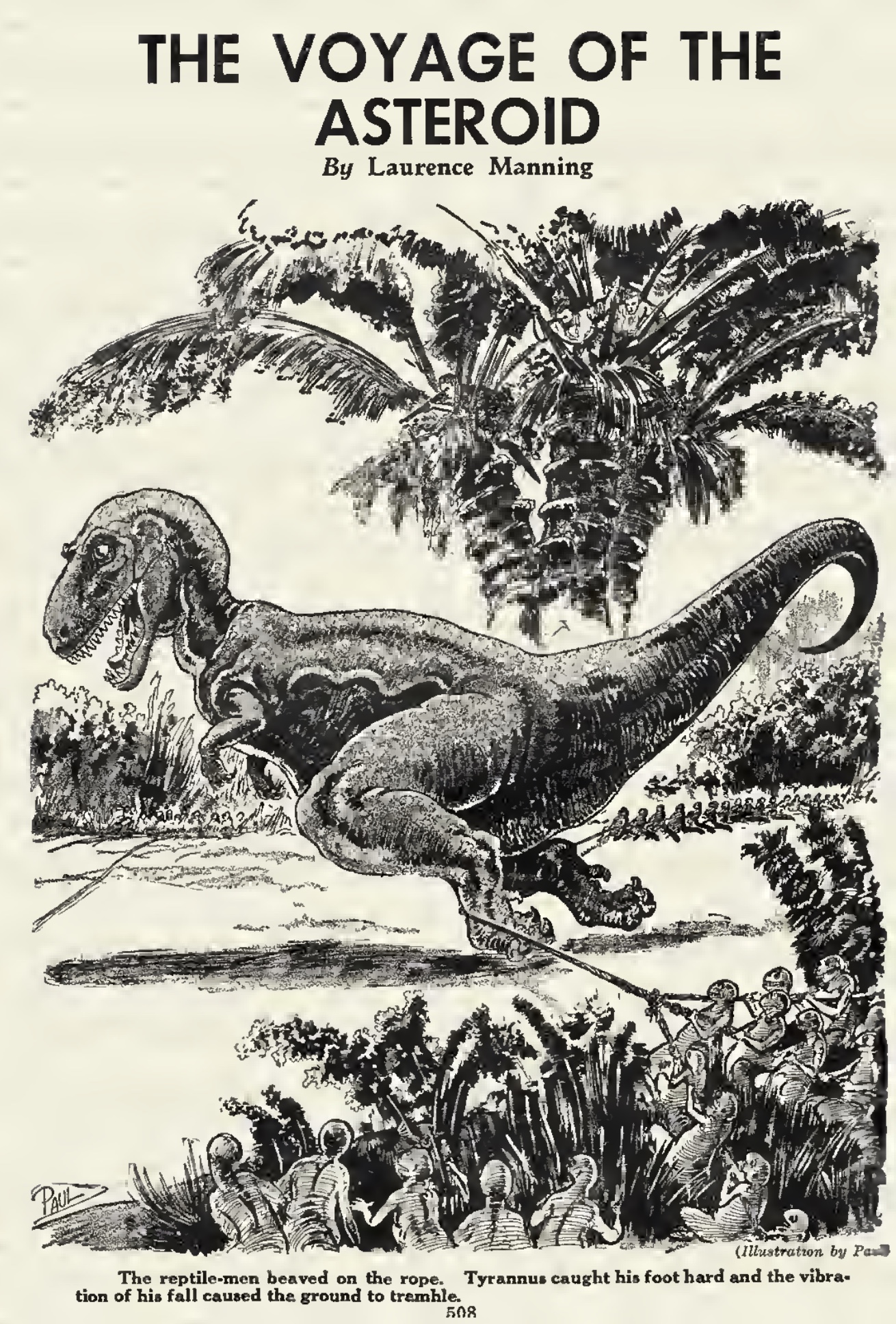

- Laurence Manning’s “The Voyage of the Asteroid” (Summer 1932 Wonder Stories Quarterly) and “The Wreck of the Asteroid” (December 1932-February 1933 Wonder Stories. Ashley’s Time Machines calls the sequel one of the best stories of the period; realistically depicts space travel and exploration on Venus. SFE: Manning’s style was very much of his time, but he had a more wide-ranging imagination than many of his colleagues. Fun facts: Canadian-born author, in the USA from 1920, a founder of the American Interplanetary Society and editor of its journal, Astronautics, who began to publish work of genre interest with “The City of the Living Dead” with Fletcher Pratt for Wonder Stories in May 1930. He is best remembered for his numerous contributions to Wonder Stories and Wonder Stories Quarterly in the 1930s.

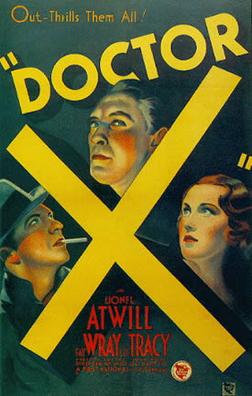

- Doctor X is a 1932 American pre-Code mystery horror film produced jointly by First National and Warner Bros. Based on the 1931 play originally titled The Terror by Howard W. Comstock and Allen C. Miller, it was directed by Michael Curtiz and stars Lionel Atwill, Fay Wray and Lee Tracy.

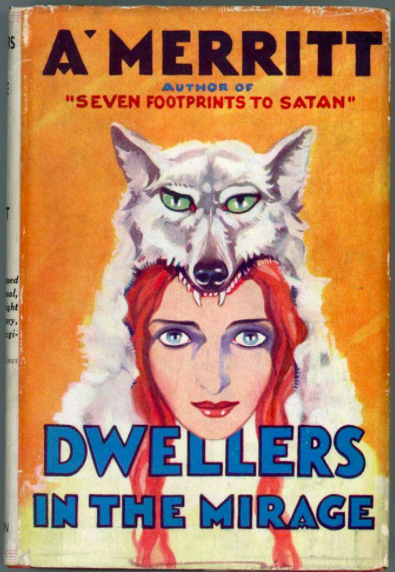

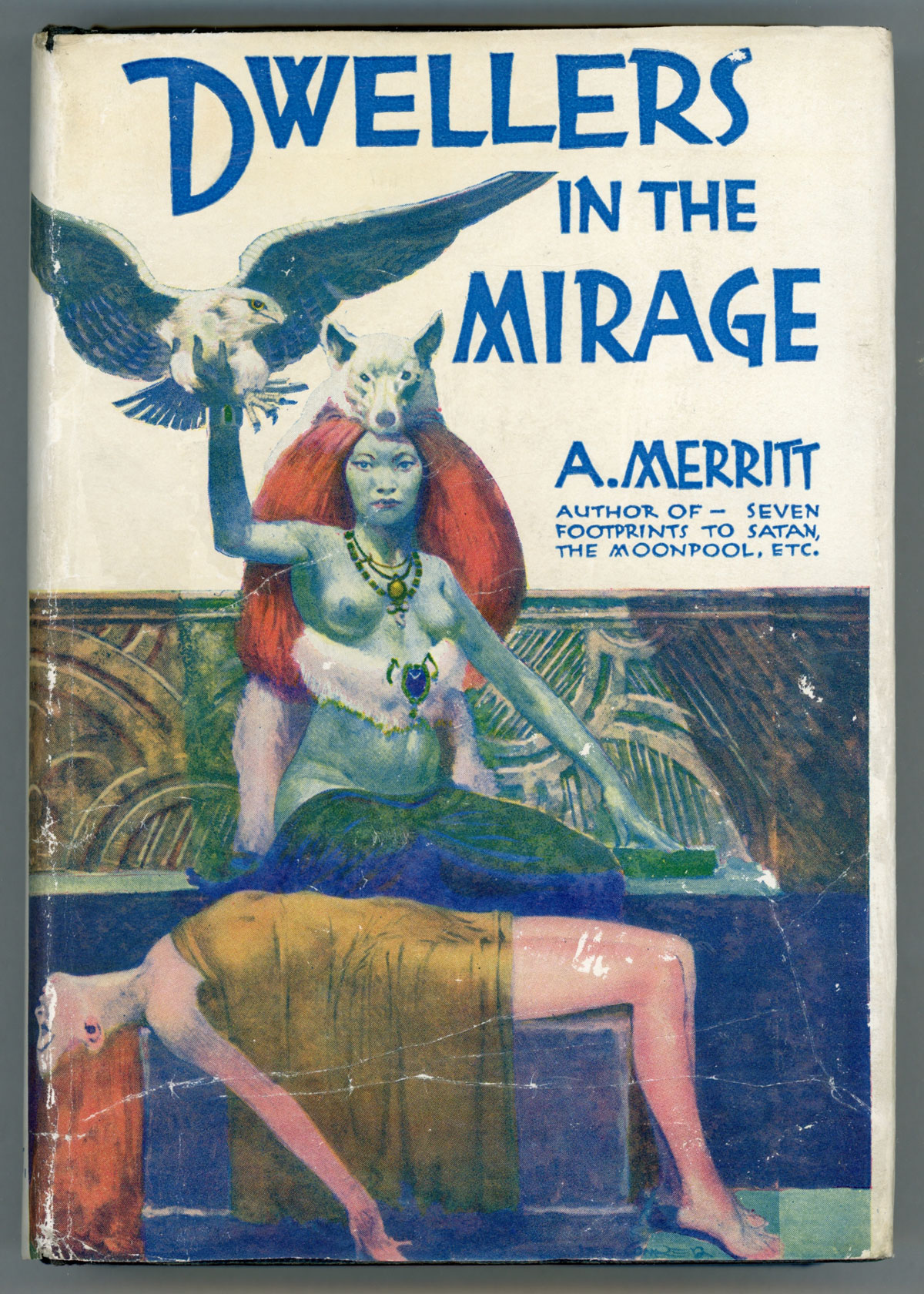

- A. Merritt‘s Dwellers in the Mirage. Science fantasy? Hiking in northern Alaska, explorer Leif Langdon and his Native American friend discover a Hggrd-esque hidden valley inhabited by golden-skinned pygmies and the descendants of Mongolians. Soon Langdon, who was once told he was a descendant of Dwayanu, an ancient Mongolian king, finds himself possessed by the spirit of Dwayanu. Langdon/Dwayanu starts a civil war between the valley’s inhabitants; can he fight off the influence of his ancestor? Meanwhile, Merritt is in top form: we encounter giant leeches; a Cthulhu-esque octopoid creature — from another dimension — that dissolves whatever it touches; and a beautiful witch woman! Fun fact: One of Michael Moorcock’s favorite fantasy novels. Dwellers in the Mirage was originally serialized in Argosy beginning with the January 23, 1932 issue.

- Elfred Berggren’s Robotarnas gud (God of the Robots). Swedish story by a young engineer, markedly inspired by Karel Čapek’s R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots, but nevertheless an impressively imaginative and stylistically mature work. It was posthumously issued, since Berggren suffered from tuberculosis and died at twenty-nine. Full text.

- Erle Stanley Gardner’s “New Worlds” — a catastrophe novella.

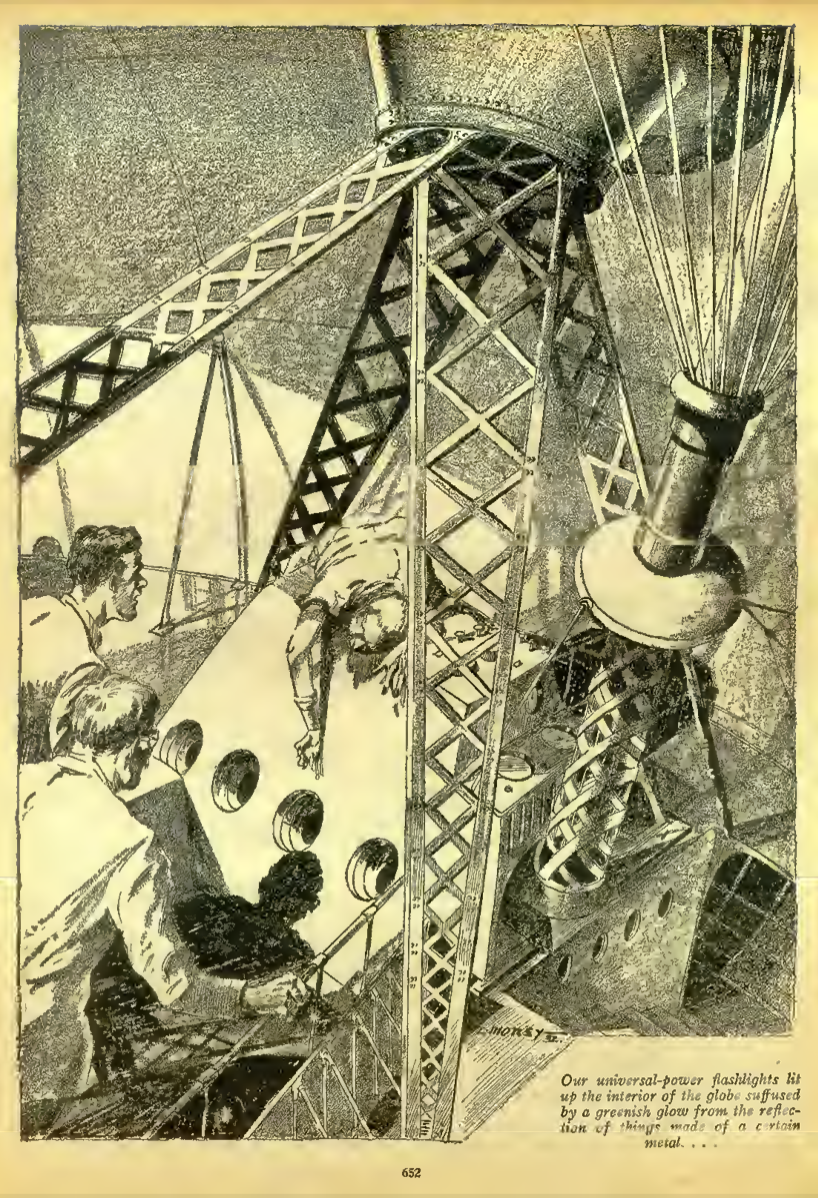

- Harl Vincent’s “Power” — a dystopian pulp story.

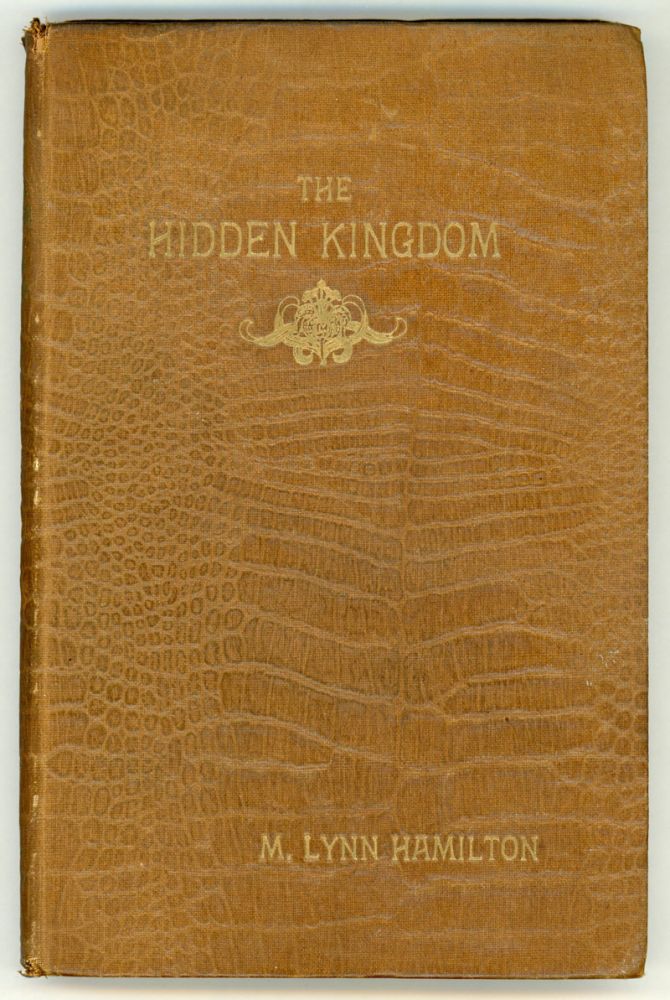

- M[arianne] Lynn Hamilton’s The Hidden Kingdom. Utopian lost race novel. A doctor is kidnaped and taken to “Ordsborough,” a thriving hidden utopian community on a plateau in northwest Australia ruled by Colonel Ord. A “Provides a crisp updating the hidden world motif of the earlier romances … The book is weakened, as usual, by the exigencies of love interest.” – Blackford, et al., Strange Constellations: A History of Australian Science Fiction.

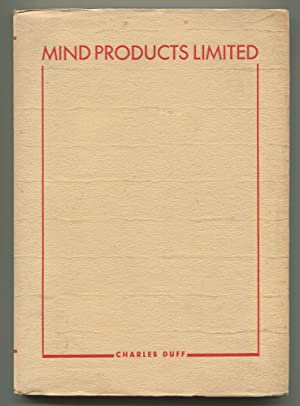

- Charles Duff’s play Mind Products Limited, a three-act play depicting the world of 1960 — a world involving mind control (and X-ray vision), carplanes and television phones, “a Čapek-like vision of totalitarianism in a world gone — subversively — mad” as John Clute puts it.

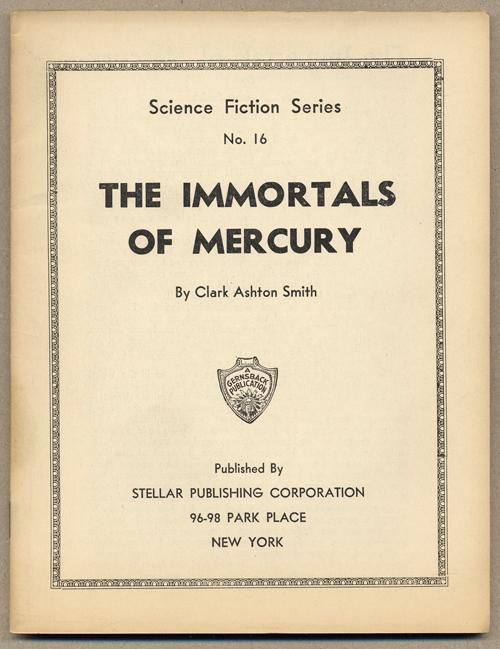

- Clark Ashton Smith’s The Immortals of Mercury. A conspicuously uneasy space opera. It initially seems to be an attempt to write sf without the ornate accoutrements Smoth usually deployed. An explorer on Mercury is kidnapped by savage natives, saved by seemingly advanced immortals who live underground, but finds that his protoplasm is necessary to keep them alive, and he escapes. At this point, instead of following his protagonist’s climb back upwards to his ship in normal sf fashion, Smith depicts his panicked course deeper and deeper into the horrors beneath Mercury, eating helpless monsters to stay alive as he goes, emerging finally, dehumanized and frozen, on the night side of the planet, where he freezes to death.

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “Dream in the Witch House” (Weird Tales, July 1933) — Walter Gilman, a student of mathematics, lives in the house of one of the Salem’s witches. The witch, it seems, had spoken of “lines and curves that could be made to point out directions leading through the walls of space to other spaces beyond” — so Gilman wants to understand how she’d achieved “an insight into mathematical depths perhaps beyond the utmost modern delvings of Planck, Heisenberg, Einstein, and de Sitter.” In a dream, he travels to the fourth dimension — “prisms, labyrinths, clusters of cubes and planes, and Cyclopean buildings.”

- Harry Stephen Keeler’s The Box from Japan. Set in the near future of 1942, with various eccentric predictions including a new food source (the Giant Sugar Cactus), the return of Prohibition, and holographic color TV.

- S.S. Held’s La Mort du Fer (The Death of Iron; 1931, translated in Wonder Stories, September-December 1932, as “The Death of Iron”). Picks up the theme of Raoul Bigot’s ‘Le Fer Qui Meurt’ (15 December 1918) in an elaborately extrapolated fashion. “The novel is considerably more sophisticated in its writing and thinking that the other works translated for Hugo Gernsback’s pulp magazines.” — Stableford, The Plurality of Imaginary Worlds: The Evolution of French Roman Scientifique.

- Mato Hanžeković’s Gospodin čovjek (Cooperative Press Institute; I’ve seen the title translated as “Mr. Man” and “Man, the Noble”), the first utopian novel in Serbo-Croatian literature, one hears. Also called one of the two most important Yugoslavian sf novels published in the period up to the beginning of World War Two. Hanžeković was founder and editor of the monthly Hrvatski žak i Književnik, the weekly Hrvatska istina, editor of the Hrvatski dnevnik and the culture section of the daily Gospodarstvo. His most successful and modern literary creations are considered to be his travel diaries Letters from Lumbarda (1923).

- Clifford D. Simak’s “Mutiny on Mercury.”

- Clifford D. Simak’s “The Voice in the Void” (Spring 1932 Wonder Stories Quarterly), about the desecration of a sacred tomb on Mars which possibly contains the relics of a messiah from Earth. An early work of sf interest from Simak. Ashley’s Time Machines notes it explores religious themes.

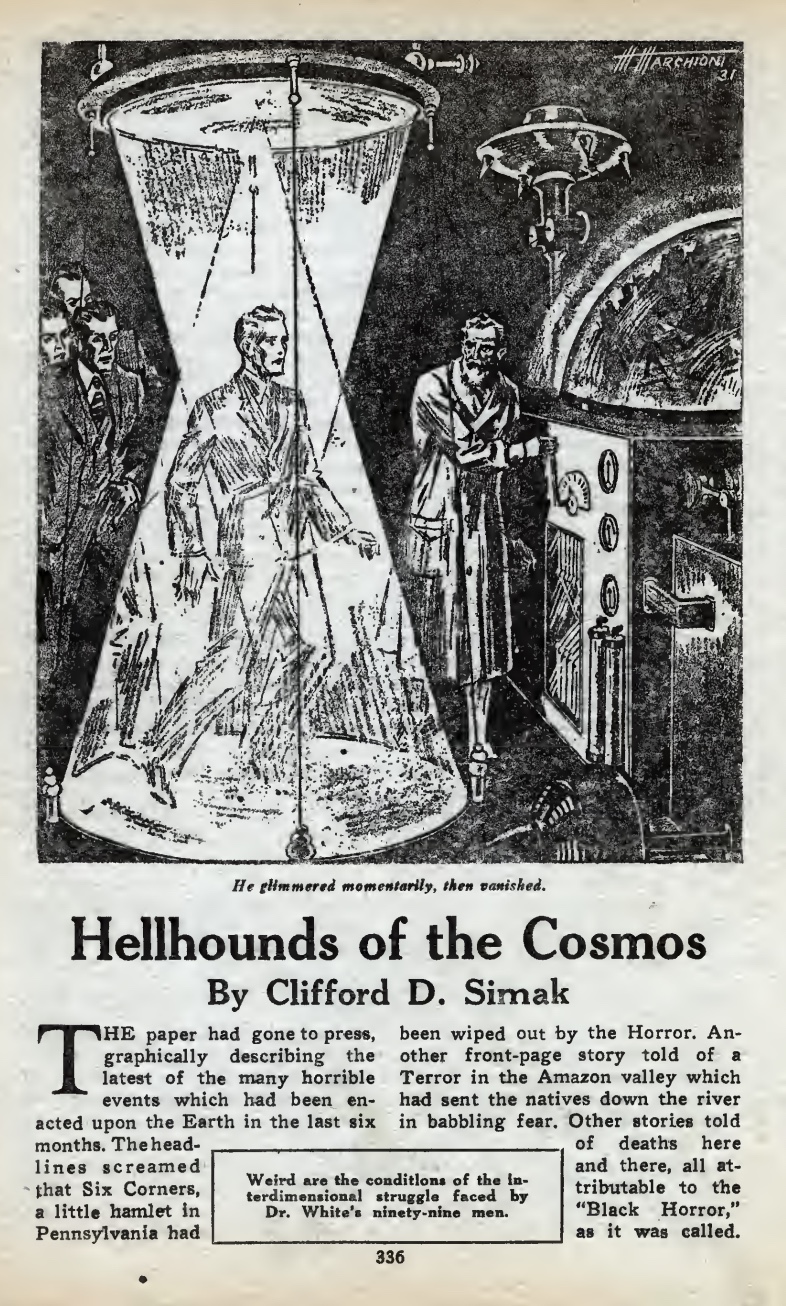

- Clifford D. Simak’s “Hellhounds of the Cosmos” (June 1932 Astounding), in which defenders of Earth who, in order to fight a monster in another dimension, combine into a gestalt. “Weird are the conditions of the interdimensional struggle faced by Dr. White’s ninety-nen men.”

- Clifford D. Simak’s “The Asteroid of Gold.”

- David H. Keller’s The Metal Doom (May-July 1932 Amazing). Keller was a conservative, anti-feminist, racist sf author, one hears. Advanced civilization ends when all metal begins to rust. Like most Keller stories of this sort, it starts strongly but dwindles into inconsequence.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “A Conquest of Two Worlds” (Wonder, February 1932). Now that space opera was outlawed in Wonder, we see interesting new premise. Here, Earth colonists are exploitive alien invaders. Hamilton’s hero seeks to stop the exploitation of Jovians by other space explorers. Editor’s note: “Just as the white man had nothing to be proud of in his early conquest of the Americas, so the human race will hardly look back with pride if it manages to conquer the solar planets. The dominating force of greed is not expected to suddenly vanish when enterprising men roam the interplanetary spaces.”

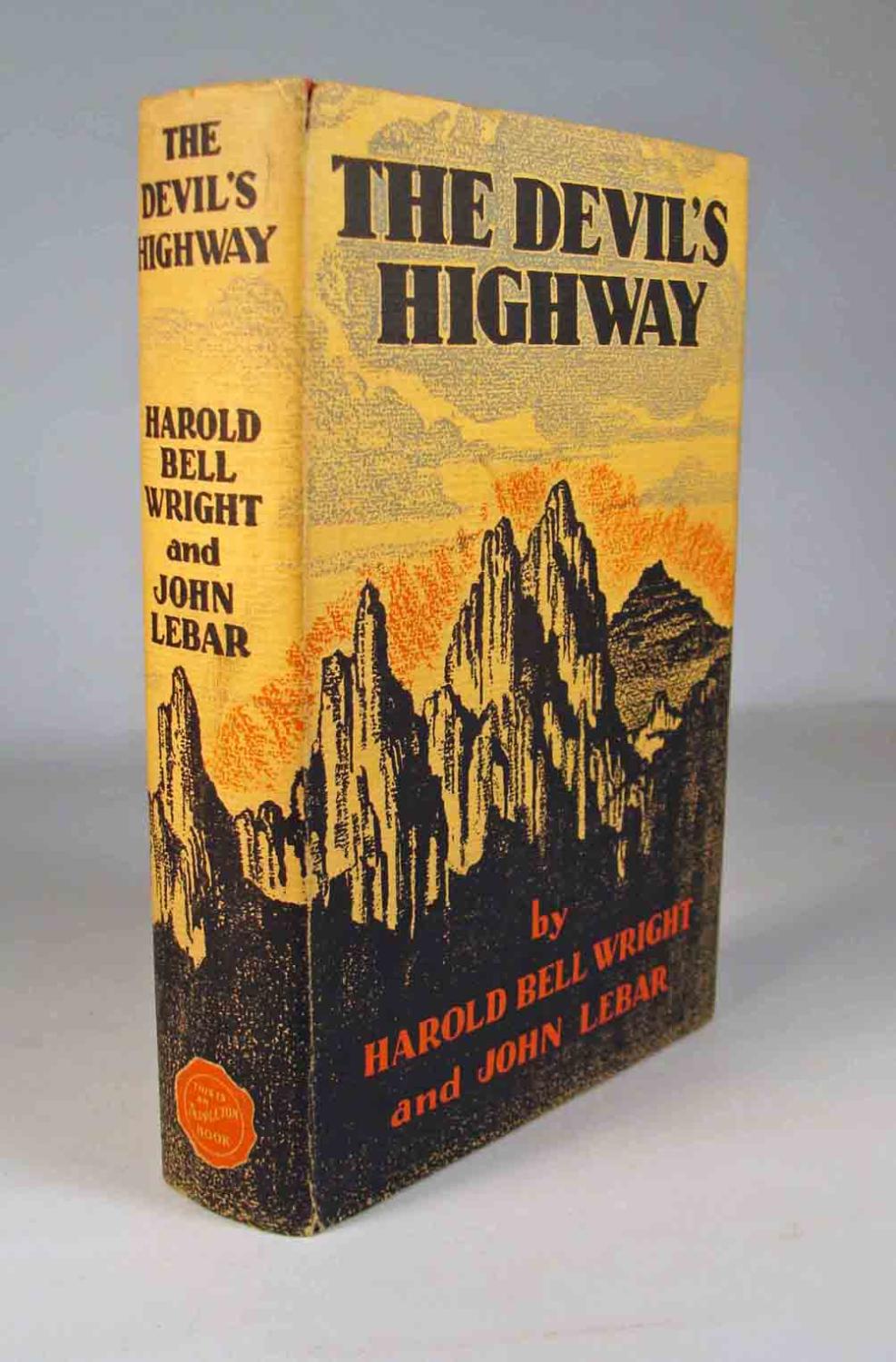

- Harold Bell Wright and John Lebar’s The Devil’s Highway — according to The Anatomy of Wonder, this is one of the best mad scientist stories. The mad scientist and his culpable colleagues have invented a thought-control device operating with the help of a power source called “ethericity”; it suppresses the better instincts of its victims. They are then inclined, out of bitterness, to further his plot to eliminate Homo sapiens (his motive being that he is a dwarf who had been maltreated as a child). Fun fact: Wright is said to have been the first American writer to sell a million copies of a novel and the first to make $1 million from writing fiction. Wonder Stories panned Wright’s only science fiction novel, The Devil’s Highway, saying “If not for the mawkish sentimentality, and endless moralizing of this book, it might have been an interesting piece of work”. Amazing Stories, however, found the novel “a very creditable attempt at combining two almost incompatible conceptions: The psychic and the physical” and concluded that The Devil’s Highway “is quite enjoyable, as it is logical and exceedingly well written.” Fun fact: “John Lebar” is the nom de plume of Wright’s son Gilbert Munger Wright.

- Harold Nicolson’s “Public Faces.” Political fantasy about the development of atom bomb — mentioned in Anatomy of Wonder.

- J. Leslie Mitchell’s Three Go Back (cut and bowdlerized December 1943 by Famous Fantastic Mysteries; this mutilated version reissued 1953). A collection of linked stories in which a pacifist, an arms manufacturer, and a woman radicalized by the idiotic death of her lover in war are passengers on an airship, which is hurtled by timeslip back to an Stone Age mid-Atlantic Atlantis. They find there unspoiled proto-Basques in an Eden doomed by the nearing Ice Age and by conflicts with savage Neanderthals; the two surviving castaways then snap back to the present. The book is notable for its sentimental but strongly held idealization of prehistory as a Golden Age, and for its realistic and ebullient female protagonist, who adapts far more readily to her strange surroundings than either of the men. This is Prehistoric SF imbued with the expository thrust of the Scientific Romance.

- Jean-Louis Njemba Medu’s Nnanga Kôn. A Bulu-language sf/fantasy novel, the title of which means “white ghost” or “phantom albino.” Medu’s novel, which casts white colonialists as technologically advanced supernatural beings, won the International African Institute Competition for 1932. It has been described as a powerful first-contact narrative. It became so popular in Medou’s native Cameroon that it became the basis of local folklore. More than 30 years after the author’s death, the novel was translated into French (as Le Phantom Blanc) by Jacques Fame Ndongo, and published by Sopecam publishers of Yaounde in 1989.

- Shaemas O’Sheel’s It Never Could Happen, or The Second American Revolution. This political fantasy uses the dispersal of the Veterans’ “Bonus Army” in July 1932 as its point of departure. The skeletal narrative is presented as a future history published in 1982, THE VETERANS’ REVOLUTION OF 1932, whose first-person narrator is General Elmer Hicks, formerly commander-in-chief of the U.S. forces.

- John Buchan’s The Gap in the Curtain. Buchan’s only sf novel proper, in which his character Leithen participates. A Nobel Prize-winning scientist exposes seven members of the British upper classes to an experience of precognition of the near future, based on the time theories of J.W. Dunne. Each sees, in an issue of the London Times from one year hence, an unmistakable reference to his fate (the only woman involved has fainted too soon to see what will happen to her); as a result an entrepreneur becomes involved in the exploitation of michelite, a new mineral which cannot be dented and cannot corrode; others become involved in near-future politics; and one comic narrative, taking off from Wodehouse, is an Appointment in Samarra tale with a happy ending. The focus of the episodes told within this frame is on the nature of character, which is infinitely mutable, not on the future, which (properly understood) is fixed.

- John Gloag’s To-morrow’s Yesterday. Bitter satire, scathing about English complacency. SFE mentions it as an example of foreboding about how we might lead to the end of civilization.

- John Gray’s Park: A Fantastic Story, a gently humorous novel. Catholic priest Father Mungo Park dreams of a timeslip visit to a future utopian Britain now colonized by black African Catholics, while the descendants of the former white population are primitive degenerates living underground, perhaps in echo of Wells’s Morlocks. A similar racial reversal scenario features in Evelyn Waugh’s short story “Out of Depth” (see 1933).

- John W. Campbell’s “The Last Evolution” (1932, Amazing Stories). Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2020.

- John W. Campbell’s Invaders from the Infinite (Amazing Stories Quarterly, Spring 1931). An Arcot, Morey, Wade novel. The team help an alien race against a universal menace. Ashley’s Time Machines notes that some call this story the “apex of space opera.” Uses some clever ideas such as harnessing the emotions as weapons. Bleiler: “The early John W. Campbell story par excellence: weak novelistic skills combined with very strong speculative, imaginative theoretical physics. While one may be bored with [the] interminable lectures and rendered drowsy by the repeated space battles, but one must also admire Campbell’s ingenuity in creating novel artifacts.”

- John Wyndham (John Beynon Harris)’s The Lost Machine. A novella in Amazing Stories April 1932. A robot commits suicide, after being stranded on Earth — a touching story. – Mentioned by Moskowitz in Seekers of Tomorrow as “remarkable.” He began publishing work of genre interest with “Worlds to Barter” as by John Beynon Harris in Hugo Gernsback’s Wonder Stories for May 1931, contributing several more tales to that market through the early 1930s.

- John Wyndham (John Beynon Harris)’s “The Venus Adventure” (Wonder Stories May 1932). Loss of innocence on Venus when a puritanical space pioneer corrupts the planet’s natives. Moskowitz calls it “remarkable.”

- Leslie F. Stone (Leslie Frances Rubenstein)’s “The Hell Planet.” Critical of colonialism – more realistic than space opera – the horrors of the planet Vulcan. Stone remains best known for “The Conquest of Gola” (April 1931 Wonder Stories).

- Leslie F. Stone’s “The Man who Fought a Fly.”

- Maurice Renard’s Celui qui n’a pas tué (He Who Did Not Kill). Though announced as a 1932 title with galley proofs printed, it was not published owing to the bankruptcy of its Paris publisher Georges Crès; it finally appeared in 2019. One of his collections containing stories, mostly extremely short, on a great variety of sf themes: clones, invisibility, time travel, cyborgs, gravity, time paradoxes, Eechatology and, especially and often, altered modes of Pprception.

- Murray Leinster’s “Politics” (Amazing Stories, June 1932). America’s Army and Navy take on and defeat a superior invading force despite the cowardly pacifism of the country’s political class. PS: Leinster was one of the few science fiction writers from the 1930s to survive in the John W. Campbell era of higher writing standards, publishing over three dozen stories in Astounding and Analog under Campbell’s editorship.

- Neil Bell’s “The Facts About Benjamin Crede.” A sarcastic messianic fantasy, in the July 1932 The London Mercury.

- Philip Wylie’s The Savage Gentleman. A child is brought up isolated from humanity on an island bearing traces of a lost world (perhaps Atlantis), and excoriates the social world when finally exposed to it. PS: Pulp historians point out that the themes of The Savage Gentleman are replicated to an uncanny degree in the pulp character Clark “Doc” Savage (1933) created by Lester Dent.

- Raymond Z. Gallun’s “The Revolt of the Starmen.”

- Richard Vaughan’s “The Woman From Space” (Spring 1932 Wonder Stories Quarterly). In which Earth is under threat from an errant planet and which women from that planet take over when the men destroy themselves, then look for husbands on Earth. Features an array of superscientific gadgetry. Mentioned in Moskowitz’s collection When Women Rule. Ashley’s Time Machines notes that the story looks at how men had all but destroyed themselves in an unrelenting war and it was left to women to establish utopia. PS: The author, believed to have been Canadian, wrote only two known stories, the first being “The Woman from Space.”

- Thomas S. Gardner’s “The Last Woman.” Only one woman, kept alive in a zoo, visited by aliens. Mentioned in Moskowitz’s collection When Women Rule. Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

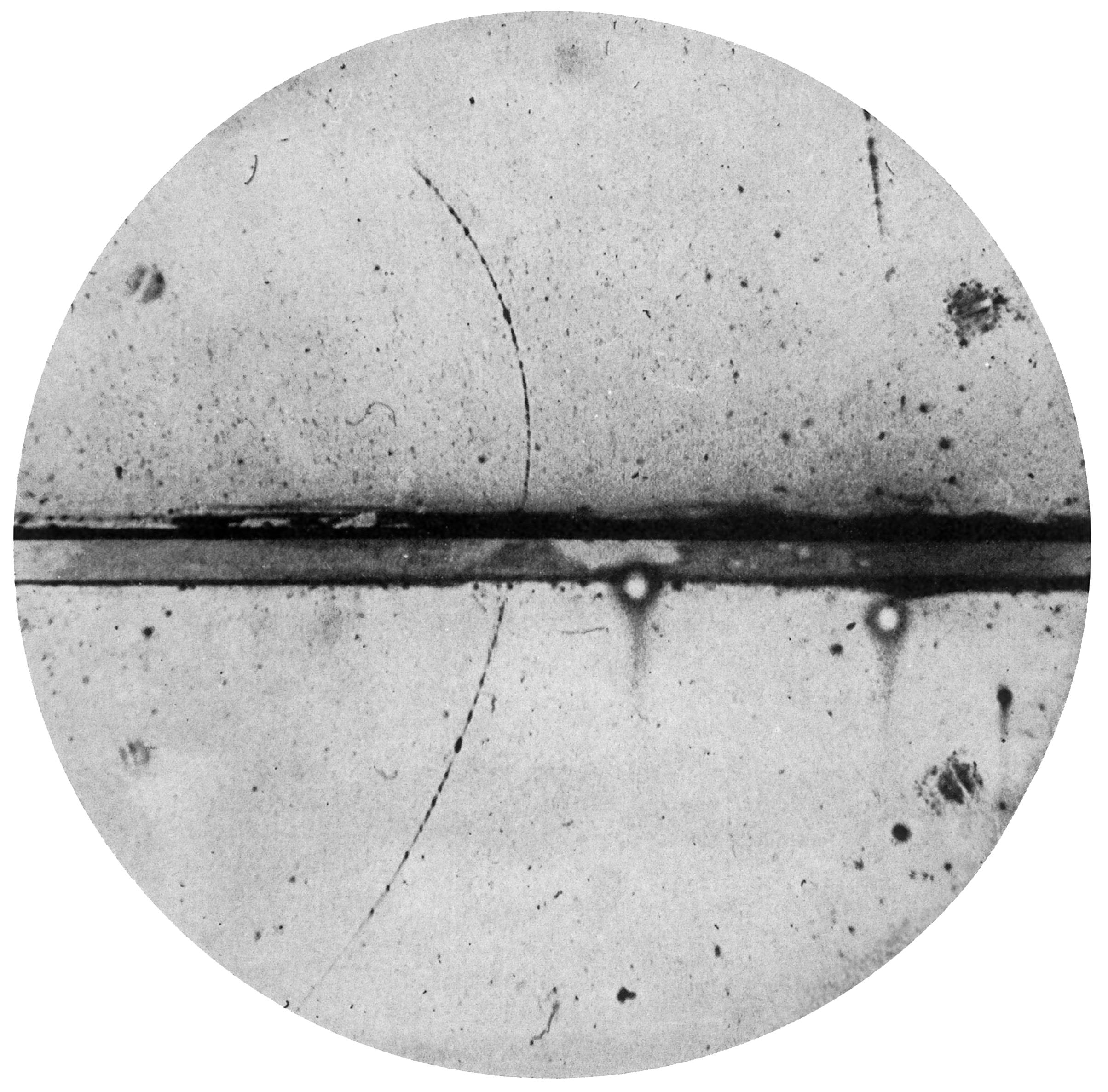

ALSO: Anderson discovers positron (the first evidence of antimatter); Chadwick discovers the neutron; Heisenberg wins Nobel in Physics for the creation of the matrix theory of quantum mechanics. Carothers synthesizes polyamide (nylon in 1936). Gandhi arrested; Hitler refuses Hindenburg’s offer to become Vice Chancellor; Franklin D. Roosevelt becomes US president. Bergson’s The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, his fourth and final principal work. Earhart is the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic; kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby. Graham Greene’s Stamboul Train (also known as Orient Express), Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House in the Big Woods, Hergé’s Tintin adventure Les Cigares du Pharaon (serialized 1932–1934), Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty. Brecht’s St. Joan of the Slaughter Houses, Celine’s Voyage au bout de la nuit. Calder exhibits “stabiles” and “mobiles.” Grand Hotel with Garbo, Weissmuller’s first Tarzan movie. “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” a popular song in the US.

Until 1932, the atom was believed to be composed of a positively charged nucleus surrounded by negatively charged electrons. In 1932, James Chadwick bombarded beryllium atoms with alpha particles. An unknown radiation was produced. Chadwick interpreted this radiation as being composed of particles with a neutral electrical charge and the approximate mass of a proton. This particle became known as the neutron. With the discovery of the neutron, an adequate model of the atom became available to chemists.

Since 1932, through continued experimentation, many additional particles have been discovered in the atom. Also, new elements have been created by bombarding existing nuclei with various subatomic particles. The atomic theory has been further enhanced by the concept that protons and neutrons are made of even smaller units called quarks. The quarks themselves are in turn made of vibrating strings of energy. The theory of the composition of the atom continues to be an ongoing and exciting adventure.

Wild Talents, published in 1932, is the fourth and final non-fiction book by Charles Fort. Fort’s writing style and tongue-in-cheek sense of self-deprecating humor is prominent, here, particularly in the section on his own purported psychic experiences. Fort discusses many topics he had touched on before — poltergeists, spontaneous human combustion, animal mutilations, vampires, and ghosts — along with many supposed cases of psychokinesis and ability to control one’s surroundings. His thesis is that in primeval times, man needed such extraordinary powers in order to survive in the wilderness, and that all people can potentially (re-)develop these powers if they literally put their mind to it. He also explores alleged cases of witchcraft and murder by mental suggestion, compiling an impressive list of “occult criminology” in support. He attacks the scientific taboo which he feels prevents “wild talents” from being accepted. Fort also plays around with the idea that humans are able to transform into animals at will.

“Radium — Boon or Menace?” was the title of a June 1932 article in Everyday Science and Mechanics. Its author interviewed 6 specialists and came up pretty much with the consensus we have today: radium can treat cancer pretty well sometimes. Sometimes it works the way you want, sometimes it doesn’t, but in any case always make sure the radium is contained and please don’t eat it.

As a student in the School of Engineering at George Washington University from 1930, L. Ron Hubbard became acquainted with Paul Linebarger (Cordwainer Smith), a fellow student, who as editor of the Literary Supplement of The Hatchet, the college paper, published Hubbard’s first story, “Tah”; this was not sf. Hubbard’s prolific career as an sf writer wouldn’t begin until 1938.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin