RADIUM AGE: 1901

By:

April 24, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the cultural era of the Nineteen-Oughts begins c. 1904. So the first few years of the Twentieth Century should be regarded as a kind of interregnum between sf’s Scientific Romance era and the Radium Age. As we look at the years 1900–1904, say, we will find elements of both eras intermingling; and all traces of the Scientific Romance era will not vanish even after 1904.

By 1901, the Theosophists Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater could claim, in the introduction to Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation, that Curie’s discovery of radium and Röntgen’s X-ray photos (which had caused a global sensation in 1896) had “revolutionized the concept of matter and are leading science into the astral world.” Occult notions of “astral sight” or “four-dimensional vision” — which surpass the merely material, illusory world of the senses and give access to permanent transcendental realities — were now, occultists and psychical researchers exulted, scientifically proven. (Excerpts from Thought-Forms here.)

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1901, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: SPACE EXPLORER | FANNISH (of or relating to a dedicated or obsessive fan) | ANT-MAN.

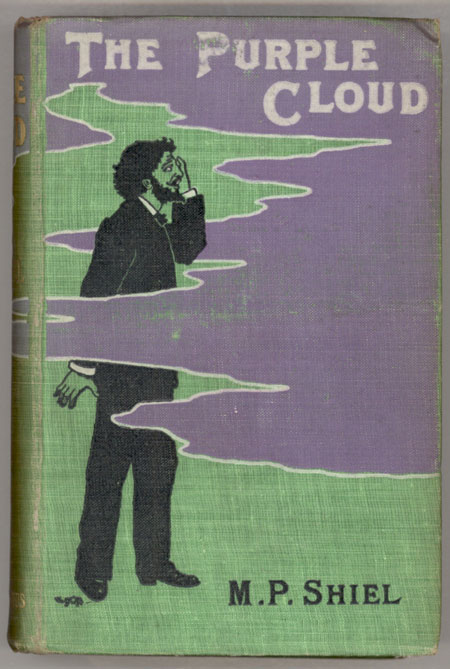

- M.P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud — an apocalyptic “last man” novel. Set around 1920, the premise is that cosmic forces of good and evil are in precarious harmony on Earth, but the balance is broken when explorers reach the north pole. Chthonic forces of destruction — a poisonous purple vapor — are released. Adam Jeffson, the explorer who reached the pole first, returns to a wiped-out world. He goes slightly mad and sets about destroying cities; he also dresses as a sultan and builds a fantastic palace. When he discovers a young woman also surviving, will they become a new Adam and Eve… or will he kill her? Born on the island of Montserrat in the West Indies, the author’s father was likely the illegitimate child of an Irish Customs officer and a female slave — making Shiel one of the very few sf authors of color during the Radium Age, not to mention perhaps the first UK novelist of Caribbean origin. He also proclaimed himself king of the island of Redonda.) Around 1899–1900, Shiel conceived a loosely linked trilogy of novels, of which The Purple Cloud was the first to see publication. The others are The Lord of the Sea (also 1901; a fantasy of history with sf elements — a controversial work because of its treatment of Judaism; Bleiler concludes that it is “somewhat offensive” but not virulently hateful) and The Last Miracle (1906). Earlier proto-sf includes the orientalist The Yellow Danger (1898). Lovecraft: “One of my favourites is M.P. Shiel, whose House of Sounds is a marvellous tour de force comparable to its obvious Poesque prototype The Fall of the House of Usher. The first half of Shiel’s novel The Purple Cloud is also a veritably stupendous piece of work.” (to Fritz Leiber, 9 November 1936)

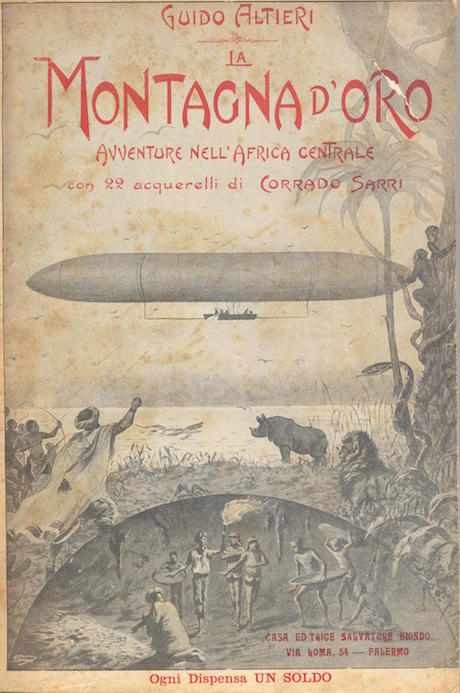

- Emilio Salgari’s La montagna d’oro (The Golden Mountain, as by Guido Altieri). Ottone Steker, German, and his companion Matteo Kopeki, Greek, venture into the heart of Africa aboard a revolutionary airship designed by Steker. The aeronauts are in search of the legendary “Golden Mountain” and its fabulous treasure, which they learned about thanks to a document from a British traveler who disappeared two years earlier. The document was found by chance by the Arab El-Kabir, a friend of the two companions, who joins them in the adventurous search. Opposing the airship’s international crew is the ruthless Altarik who, having learned of the secret, has set out to reach the hidden treasure first.

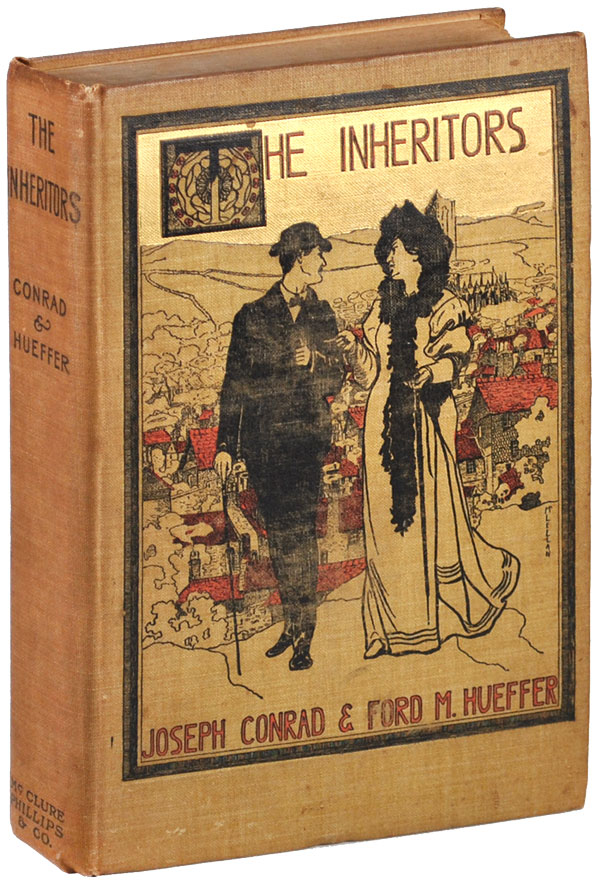

- The Inheritors: An Extravagant Story is a quasi-sf novel on which Ford Madox Ford and Joseph Conrad collaborated. It concerns a future scheme to colonize Greenland — along the lines of contemporary plans to develop the Belgian Congo. Thinly veiled political satire that has not aged particularly well. An element of sf enters when two of the leading characters — the villains — claim to be from from the fourth Dimension — a metaphor, here, for a modern generation of cold-hearted materialists. We are offered a fourth-dimension vision of “something beyond, something vaster — vaster than cathedrals, vaster than the conception of the gods to whom cathedrals were raised.” The narrator tells how, “I heard the nature of the Fourth Dimension – heard that it was invisible to our eyes, but omnipresent.” The “Dimensionists” or “Inheritors” — whose exact aims are never made clear, which sort of makes them early prototypes of the truly inscrutable alien — triumph in the end. Neither author was satisfied with the book but Bleiler says it is a “pleasant social fairy tale of morality.”

- Frank L. Pollock’s “The Invisible City” — a Black Cat story in which a hypnotist/scientist who has mastered the science of vibrations hides a city. Ultimately not super interesting. Pollock was a Canadian writer of adventure stories. Bleiler says it could have been a good novella, but the story is too undeveloped. Also the author of “The Skyscraper in B Flat” (1904), “The Crimson Blight” (1905), “Finis” (1906) and “World-Wreckers” (1908).

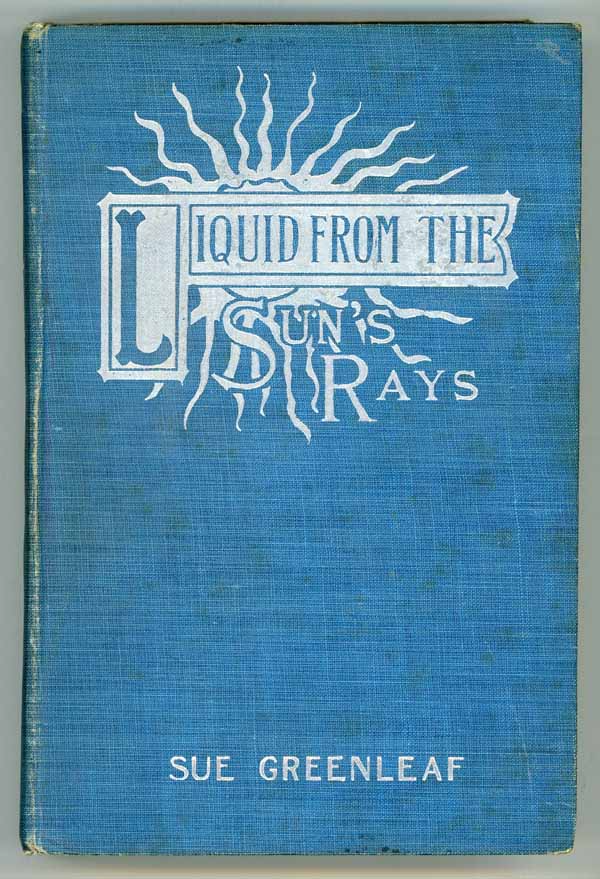

- Sue Greenleaf’s Liquid from the Sun’s Rays. Retitled as Don Miguel Lehumada: discoverer of liquid from the sun’s rays; an occult romance of Mexico and the United States. See 1906.

- Carra Depuy Henley’s A Man from Mars — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Ethel Watts Mumford Grant’s “When Time Turned” (in The Black Cat) — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women. Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers.

- Mary Anne Moore Ling’s A Woman of Mars; or, Australia’s Enfranchised Woman — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

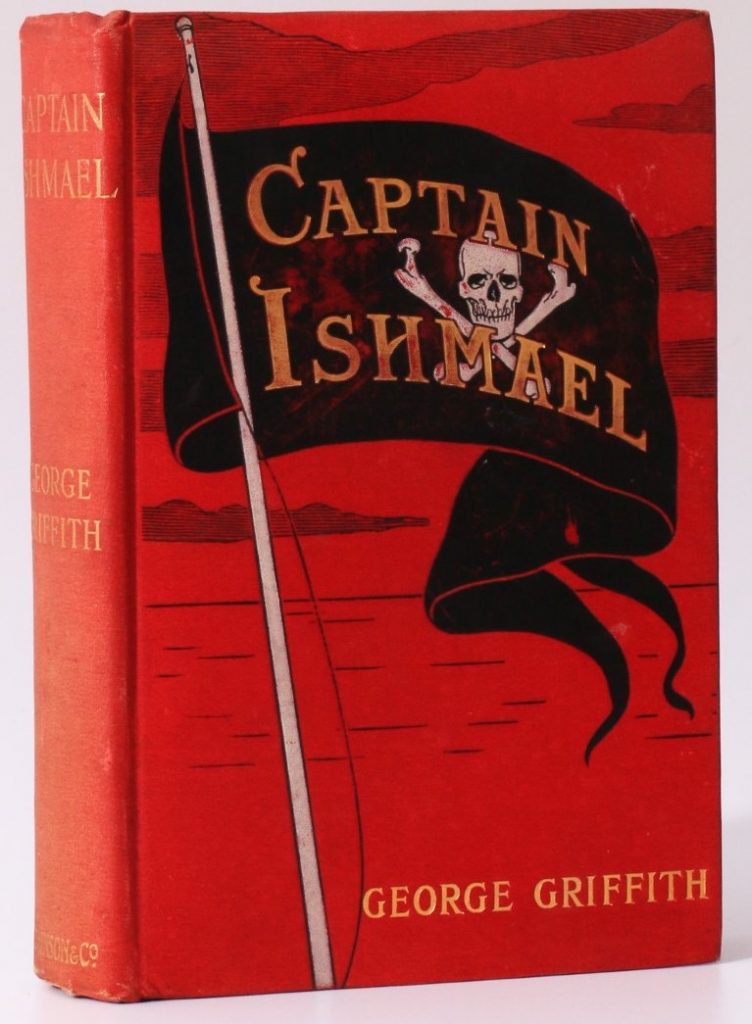

- George Griffith’s Captain Ishmael, an early example of the Parallel Worlds theme. “A man doomed to wander deathless through the ages, who several times meets the Wandering Jew, and in the end invents long-range guns with explosive shells in a ‘world of if,’ long before anybody else,” notes Moskowitz. Griffith was a prolific British proto-sf writer and noted explorer, extremely influential in the UK (but not the US).

- George C. Wallis’s “The Last Days of Earth,” which appeared in the UK’s Harmsworth’s Magazine. As the sun goes out, the last two humans prepare to leave Earth for a nearby star. Serialized at HILOBROW in 2021. Will be reissued by MIT Press as part of the collection More Voices from the Radium Age. Wallis also wrote “The Great Sacrifice” (1903), “The Star Shell” (1926–1927), and more.

- Ion Arnold’s “The Man Who Found Zero” (September 1901, The Black Cat) describes the first trip into Earth orbit.

- William Alexander Taylor’s Intermere is a utopian novel conerning the journey of a man lost in a shipwreck and saved by the commander of a hidden ancient country, Intermere. The protagonist is instructed in Intermere’s superior technology, economics, and methods of government. Taylor introduces themes on the topics of term limits for politicians, the equal distribution of wealth, and a system of motivation and reward for scientific advancement.

- Edwin Lester Arnold’s mystical proto-sf adventure Lepidus the Centurion: A Roman of To-Day. Semi-supernatural, semi-sf. Louis Allenby discovers an ancient Roman in a state of suspended animation; in contending with Lepidus for the affections of the same women, Allenby is forced to mature. Not very interesting, Arnold is best remembered for Phra the Phoenician (1890/1891) — a supernatural novel about time travel through reincarnation.

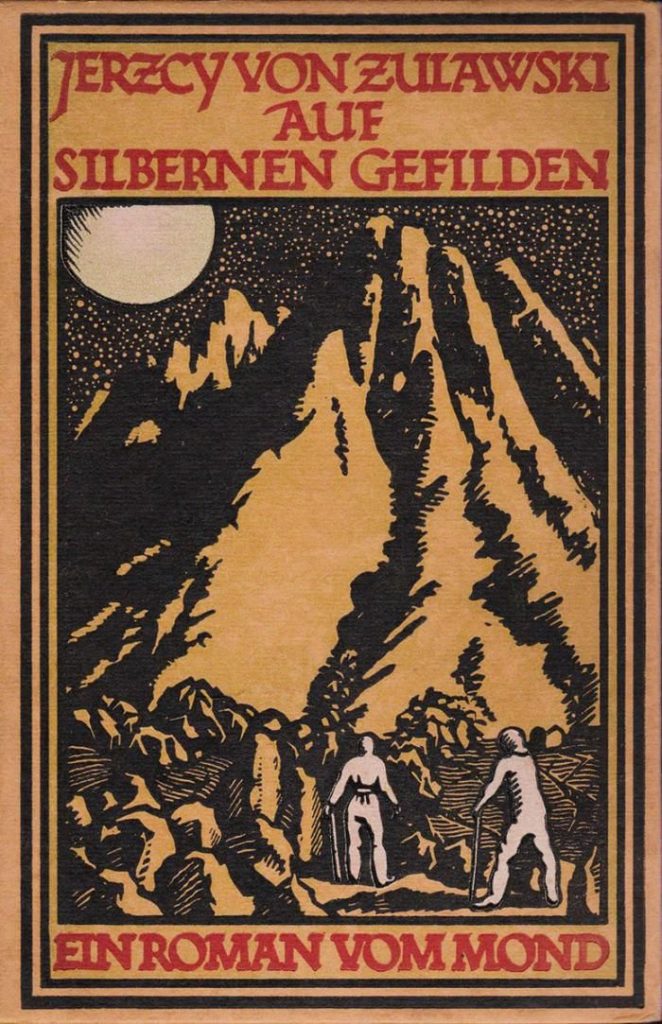

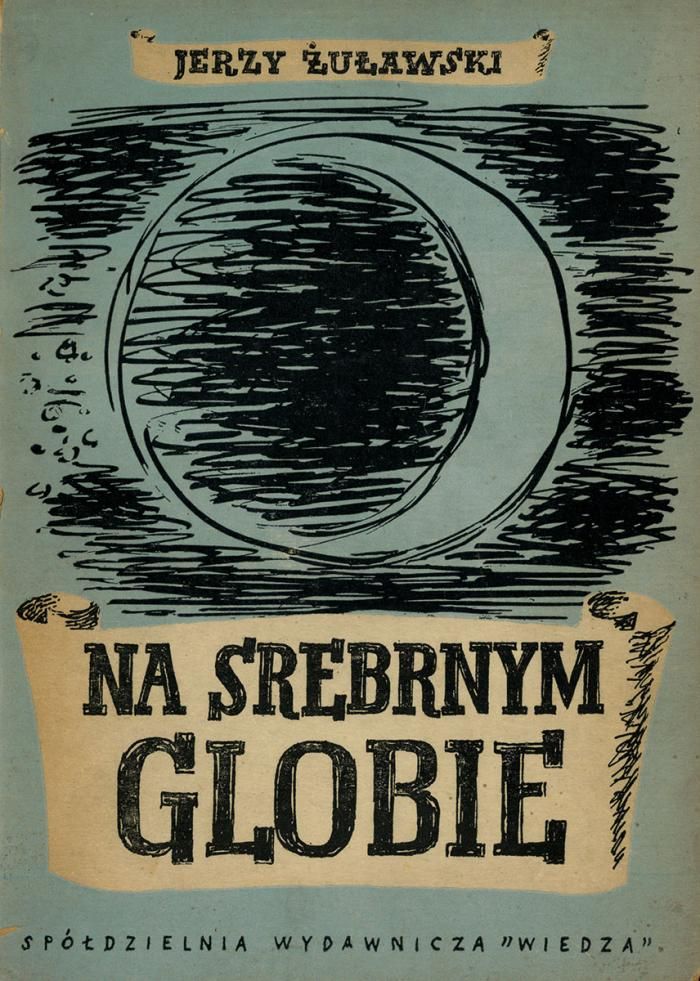

- Jerzy Żuławski’s On the Silver Globe. The Polish author is best known for his sf epic Trylogia Księżycowa (The Lunar Trilogy, 1901–1911. The first volume, Na Srebrnym Globie (On the Silver Globe) describes, in the form of a diary, the story of a marooned expedition of Earth astronauts who find themselves stranded on the Moon and founded a colony there. After several generations, they lose most of their knowledge and are ruled by a religious cult. Serialized in Głos Narodu (The Voice of the Nation, 1901–1902l as a (re-edited), 1903). The second volume, Zwycięzca (The Conqueror or The Victor, 1910), focuses upon the colonists’ anticipated Messiah, another traveler from Earth. The third volume, Stara Ziemia (The Old Earth, 1911) describes the visit of two Lunar colonists to 27th-century Earth. Read more about the trilogy here.

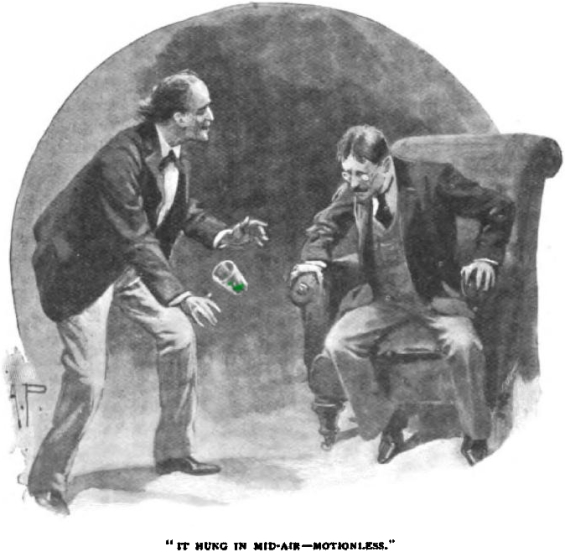

- H.G. Wells‘s “The New Accelerator.” Prof. Gibberne’s elixir accelerates all of an individual’s physiological and cognitive processes, such that the external world appears almost frozen into immobility. Bleiler calls it a “well-imagined investigation of an important motif, enlivened by an ironic touch.” Collected in From Wells to Heinlein (1979, ed. James Gunn).

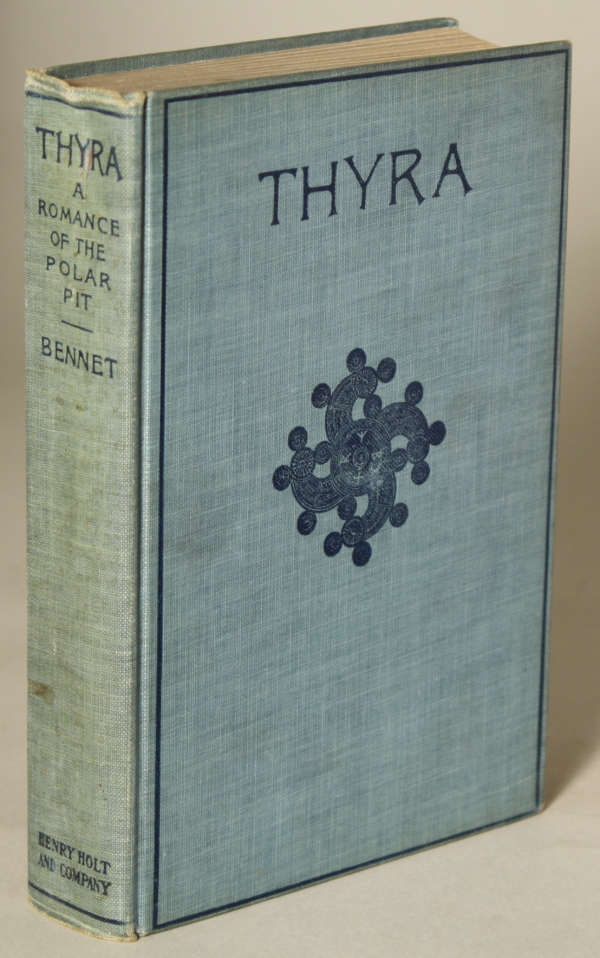

- Robert Ames Bennet’s Thyra: A Romance of the Polar Pit. A well-known lost race novel, regarded by many to be a minor classic of the genre. A quartet of explorers in a hot-air balloon drift and crash in an unexplored part of the Arctic, where they find, in a sort of hollow earth, a Norse colony, a pit with fantastic creatures, a ghoulish system of human sacrifice, and adventures aplenty. The story also involves what one could call a lost-race-within-a-lost-race. An excellent recreation of the Nordic zeitgeist. “Bennet’s description of an expedition’s thrust northward from Franz Joseph Land in 1896 provided one of the most realistic passages in the genre … THYRA pictured the full horror of Arctic exploration.” – Clareson, The Emergence of American Science Fiction: 1880-1915

- H.G. Wells‘s “A Dream of Armageddon.” A stranger in a railroad carriage tells of his dream of flying machines, pleasure cities for the wealthy — but a war breaks out (invasion of the West by Asians?). Lacks clarity.

- H.G. Wells‘s “Filmer.” The final conquest of the air in 1907. A minor effort.

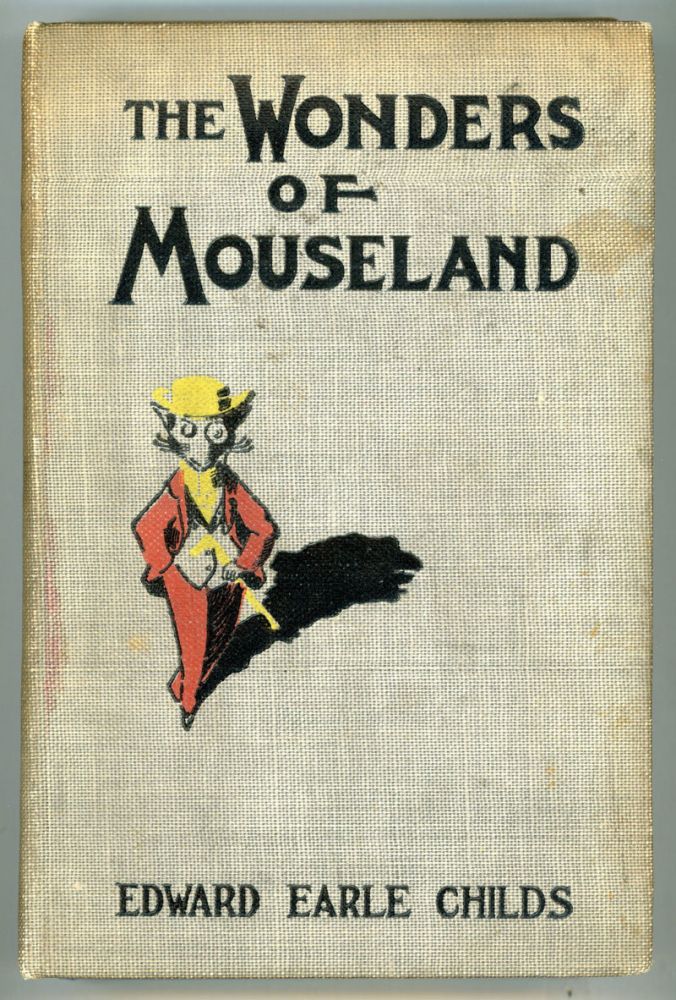

- Edward Earle Childs’ The Wonders of Mouseland. Narrator shipwrecked in the Pacific is discovered by a race of intelligent mice whose civilization is based upon information gathered from secret expeditions to lands inhabited by men. Marginally utopian, mostly satire: not a children’s book.

- James B. Nevin’s “The Whereabouts of Mr Moses Bailey” — in The Argosy — about invisibility. Two inventors discover how to make themselves invisible except for their eyes — but they can’t return to visibility. Ashley describes it as more mature than some other proto-sf of the era; it’s clearly a ripoff of (homage to?) Wells’s The Invisible Man.

- Max Ehrman’s A Fearsome Riddle. Epistolary novella about a mad scientist/mathematician who experiments on himself with drugs and sleep deprivation in effort to control or distort time. Of interest also for its detailed and rounded portrait of the black servant Blanchard. “… metaphysical speculations on time … a literate, intelligent, thought-provoking work.” – Bleiler

- Kurd Laßwitz’s “Die Universalbibliothek” (The Universal Library). Lasswitz was a German scientist, philosopher, and proto-sf author — Germany’s Jules Verne — credited with bringing sf to Germany. A playful mathematical puzzle in which four people meet — it’s a symposium-story — and discuss the desirability of creating a universal library, which would contain not only everything already written in the past but also anything possibly written in the future. The story turns from utopian speculation into dystopian unease — reflecting the era’s anxiety about the never-ending novelty of modernity. Borges picked up the idea in his essay THE TOTAL LIBRARY (1939; note that Borges claims falsely that Lasswitz “urges mankind to construct that inhuman library, which chance would organize and which would eliminate intelligence”) and later elaborated in his THE LIBRARY OF BABEL (1941). In the English-speaking world, Lasswitz’s story has been available only in an abridged version, translated by Willy Ley and published in Clifton Fadiman’s anthology Fantasia Mathematica (1958). Read it here.

- Ludwig Hevesi’s “MacEck’s sonderbare Reise zwischen Konstantinopel und San Francisco” (MacEck’s Curious Journey between Constantinople and San Francisco). The author’s real name was Ludwig Hirsch. See his 1906 collection Die fünfte Dimension (The Fifth Dimension).

- E. Tickner-Edwards’s “The Man Who Meddled with Eternity” — collected in Beyond the Gaslight: Science in Popular Fiction 1895–1905.

- L. Frank Baum’s The Master Key: An Electrical Fairy Tale, Founded Upon the Mysteries of Electricity and the Optimism of Its Devotees. Allegory for children, offering a figurative semi-supernatural source for various science-fictional devices. When a child experimenting with circuits accidentally creates a master circuit, he summons a benevolent Demon of Electricity. Who provides him with anti-gravity flight, a ray weapon, etc. Silly.

- John Davidson’s The Testament of a Vivisector. Fun fact: Scottish schoolteacher, poet, playwright and author, his intensely urban poetry, much of which focuses on science and technology from an almost mystical point of view, had a shaping influence now forgotten. He wrote Nietzschean scientific romances, while in the Testaments series, a cosmological sublime soars beyond the Nietzschean.

- Frank T. Bullen’s “The Last Stand of the Decapods” — collected in Science Fiction by the Rivals of H. G. Wells and Beyond the Gaslight: Science in Popular Fiction 1895–1905.

- Georgre Griffith’s “The Raid of Le Vengeur” — collected in Science Fiction by the Rivals of H. G. Wells.

- Philip Verrill Mighels’s The Crystal Sceptre (1901; vt The King of the Missing Links 1904; cut, with several chapters excised, under original title 1906). A young man’s balloon is driven by vast winds to an undiscovered island in the Pacific, in which Lost World he discovers two warring tribes of weapon-bearing ape-like “missing links” with some power of speech. Becoming king of the lighter-skinned tribe, he releases a white woman from the clutches of the darker-skinned society, and escapes with her. [I believe the edition shown here is 1906.] Fun fact: The author’s wife. Ella Sterling Mighels, wrote a lost-race adventure of her own: Fairy Tale of the White Man: Told from the Gates of Sunset (1915); it sites the origin of the white man in her home state of California.

- E. E. Kellett’s “The Lady Automaton” — collected in Science Fiction by the Rivals of H. G. Wells.

- Jack London’s “A Relic of the Pliocene.” The story’s narrator is camping “in the far north” where he surprisingly plays host to a campfire visitor, a fellow human with the most curious mukluk boots. The visitor tells our narrator that they are made from Mammoth hide, which our narrator scoffs at. Mammoths have long vanished from the earth, after all. Not long vanished, explains the visitor. Only recently so, for he killed the last one with his own hand…

- Jack London’s “The Minions of Midas.” An anarchist group called The Minions of Midas blackmail a wealthy magnate. The tale shows how little life is valued by both parties: on the one hand, The M of M show little remorse for the innocent victims they kill as means to put pressure on the cold-hearted magnate Eben Hale, who on the other hand, gives in to nothing. Recently adapted into a Netflix TV series.

- Samuel Butler’s Erewhon Revisited Twenty Years Later, Both by the Original Discoverer of the Country and by His Son is a belated sequel to Butler’s Erewhon (1872). It’s a satire on the origins of Christianity. Higgs returns to Erewhon and meets his former lover Yram, who is now the mother of his son George. He discovers that he is now worshipped as “the Sunchild”, his escape having been interpreted as an ascension into heaven, and that a church of Sunchildism has sprung up. He finds himself in danger from the villainous Professors Hanky and Panky, who are determined to protect Sunchildism. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature judges that it “has less of the free imaginative play of its predecessor…but, in sharp brilliance of wit and criticism, in intellectual unity and coherence, it surpasses Erewhon.”

- Rev. J. M. Bacon’s “The Fate of the Firefly” — collected in Beyond the Gaslight: Science in Popular Fiction 1895–1905.

- L.T. Meade (pseudonym of Elizabeth Thomasina Meade Smith) and Clifford Halifax, M.D.’s A Race with the Sun. Eight linked sensational mystery and detective stories related by Paul Gilchrist, a forensic scientist “whose life study has been science in its most interesting forms — he is also a keen observer of human nature and a noted traveler” (preface). Exotic poisons, hypnosis, super explosives, etc. “The Paneled Bedroom” is a tale of mesmerism and murder; in “A Race with the Sun,” rival scientists attempt to steal the formula for a new explosive, which they intend to sell to the German government. Borderline proto-sf.

- Mark Twain’s “The Secret History of Eddypus, the World-Empire” — a horrific but uncompleted vision of a future, 1000 years hence, where Mary Baker Eddy’s Christian Science rules the world, and Twain himself, the potential saviur, is confused with Adam.

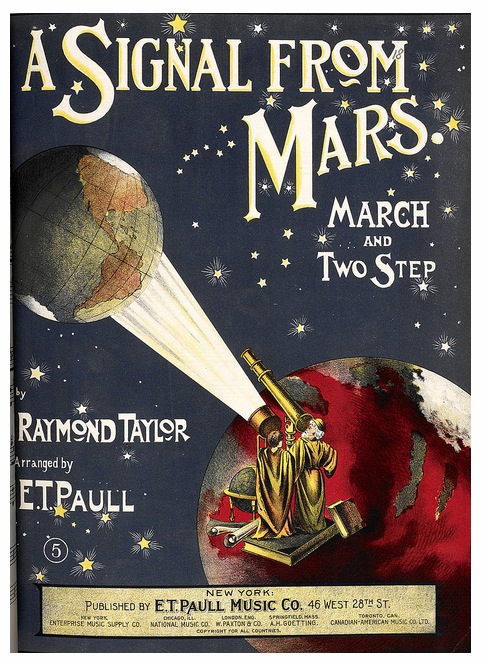

Also: American astronomer Annie Jump Cannon becomes the first to classify stars by temperature. Max Planck’s Laws of Radiation. Marconi transmits telegraphic radio messages across the Atlantic. Third Law of Thermodynamics postulated. First British submarine launched (shown above). Death of Queen Victoria, Edward VII takes the throne; Boer War still raging — introduction of the “concentration camp.” President McKinley assassinated by anarchist, succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt. Visitors to the 1901 Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, New York could take a ride called A Trip to the Moon — inspired by the Méliès movie. Kipling’s Kim, McCutcheon’s Graustark, Mann’s Buddenbrooks (indebted to Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher”). Bucke’s 1901 treatise Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind — another influence on proto-sf. Publication of an unscrupulously edited collection of notes and fragments of Nietzsche’s literary remains: Der Wille zur Macht. Selections from the Work of Fourier (1901), a translation of the French social philosopher’s utopian notions (communal property, free love) and pseudoscientific theories of “attraction,” predictions about the advancement of technology, etc., which Bleiler claims influenced some proto-sf authors of this era.

Rudolph Steiner during this period begins lecturing about what will become anthroposophy — a new religious movement that aims to study the spiritual world with comparable precision and clarity to that obtained by scientists investigating the physical world. In his unfinished autobiography, Steiner would relate that even as a child, he’d felt “that one must carry the knowledge of the spiritual world within oneself after the fashion of geometry … [for here] one is permitted to know something which the mind alone, through its own power, experiences. In this feeling I found the justification for the spiritual world that I experienced … I confirmed for myself by means of geometry the feeling that I must speak of a world ‘which is not seen’.” Published in 1901: Steiner’s Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age.

H.G. Wells’s first non-fiction bestseller was Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (1901). When originally serialized it was subtitled “An Experiment in Prophecy,” and is considered his most explicitly futuristic work. It offers the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that “my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea”).

PS: Also see the “Twilight (1901)” section of Henry Adams’ The Education of Henry Adams (1907/1918). Excerpt here.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin