RADIUM AGE: 1918

By:

August 21, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the years 1918–1919 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Teens (1914–1923).

If we were to divide the Radium Age into quarters, 1918 would be the first year of its third quarter (1918-1926). How might we characterize this sub-era? Something for me to think about.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1918.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1918, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: PLANETEER (H. E. Flint’s “The Planeteer” in All-Story Weekly).

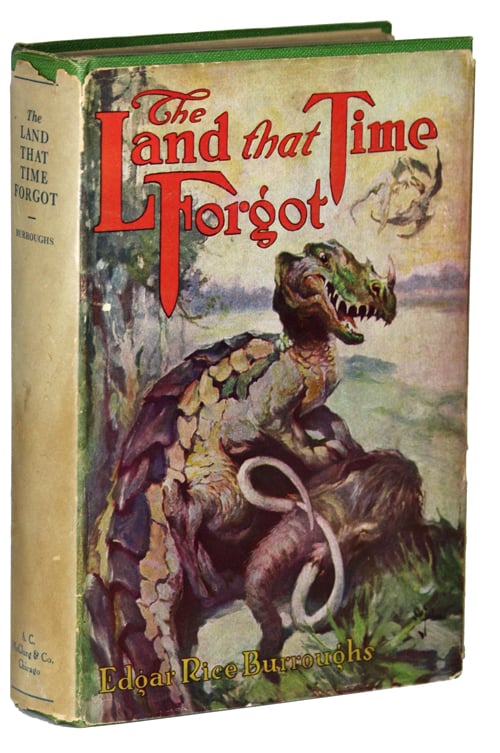

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Land That Time Forgot (1918). Of Burroughs’s non-series tales, this is considered the finest. During WWI, a shipwrecked American shipbuilder (Bowen Tyler), beautiful Frenchwoman Lys La Rue, and the crew of a British tugboat capture a German U-boat — and sail it to the Antarctic, dodging Allied ships — until they find themselves drawn to an uncharted magnetic island… inhabited by beast-men in various states of evolution. The British and German sailors agree to work together, under Tyler, to survive (Swiss Family Robinson-style) until they can somehow refuel the U-boat. However, when Lys is captured by proto-humans and the Germans abscond with the sub, Tyler must set off into the interior of the island. The tale cunningly presents in literal form the dictum that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, for individual animals on Caprona metamorphose through evolutionary stages. Fun fact: Confusingly, in 1924 it was published — along with two sequels (The People That Time Forgot, Out of Time’s Abyss) under the omnibus title The Land That Time Forgot.

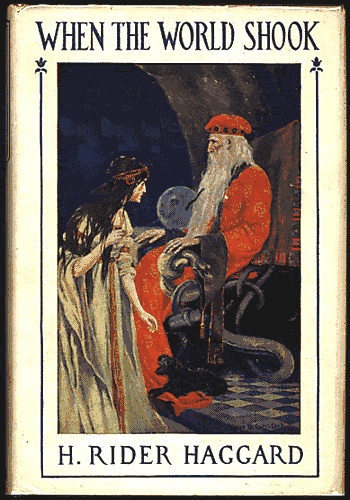

- H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook (serialized 1918–1919). When adventurers Bastin, Bickley, and Arbuthnot are marooned on a South Sea island, they discover two Atlanteans in a state of suspended animation. One of the awakened sleepers, Lord Oro, is a superman — the last king of the Sons of Wisdom, who’d relied on hyper-advanced technology to subjugate the planet’s lesser peoples. The other is Oro’s sexy daughter, Yva… who falls in love with Arbuthnot. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front. Why? To determine whether or not he should once again employ an infernal chthonic machine to drown the worthless human race, as he’d done 250,000 years earlier! Fun fact: One of the few SF tales by the author of King Solomon’s Mines and She. Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by James Parker.

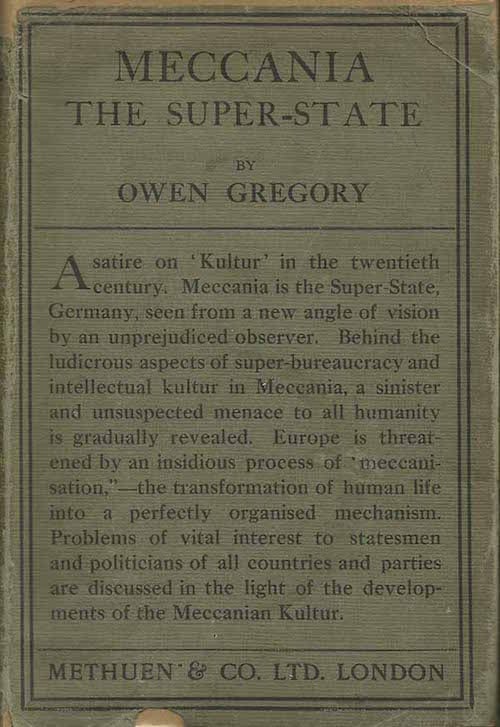

- Owen Gregory’s Radium Age science-fiction adventure Meccania: The Super-State (1918). In the year 1970, Ming, a young Chinese traveler, visits the Central European state of Meccania. Constantly monitored by official guides, Ming gets into more trouble when his personal diary — in which he notes that Meccania’s militaristic government dominates social life, that the country is a place of “perpetual propaganda” where dissenters are sent to mental hospitals and concentration camps, and that everyday life there is “an odd mixture of arrogance, xenophobia, over-punctiliousness, over-organization, chauvinism, and rigidity” — does not match the records of his guides with perfect exactness. The state maintains a eugenic breeding program; all telephone conversations are monitored; and workers’ actions are monitored and regulated in precise detail. Fun fact: This dystopian, proto-totalitarian state is obviously based on Germany; its neighbors are “Franconia” [France], “Luniland” [Britain], and “Lugrabia” [Russia].

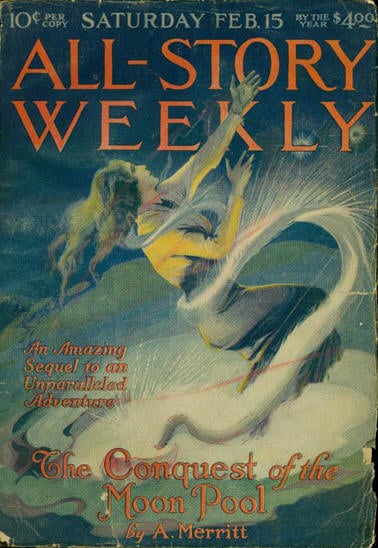

- A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool (1918–1919). The scientist Dr. Goodwin, the dashing pilot/adventurer Larry O’Keefe, and others descend into the Earth’s core — in pursuit of an entity that sometimes rises to the surface of the planet and captures men and women. In addition to a lost race of powerful, handsome “dwarves” and a lost race of froglike humanoids, the explorers discover that the entity they seek is the Dweller, essentially an AI created by an advanced race, known as the Shining Ones (ancient astronauts?). The Dweller — artificial intelligence? — has the capacity for great good and great evil, but over time is has tended to become evil rather than good. Yolara, a beautiful woman who serves the Dweller, falls in love with O’Keefe; so does Lakla, a beautiful woman who serves the Shining Ones. The adventurers must persuade or coerce the Dweller to become good — but how? Fun fact: The Moon Pool, which originally appeared as two stories (see 1919) in All-Story Weekly, is sometimes cited as an influence on Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu.” The story shot him to the front of the popularity ranks after Burroughs. Listed in the Science Fiction After 1900 timeline. Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2021–2022.

- William Butler Yeats’s “The Second Coming” (w. circa 1918-1919; November 1920 The Dial) is a dark vision of the fate of the world in the aftermath of World War One and the Spanish flu pandemic, the unspoken but manifest double catastrophe — “jackpot,” as William Gibson might put it — that awakens the “rough beast.” “The poem has increasingly been understood as an intense prolepsis of the dark future ahead” — SFE.

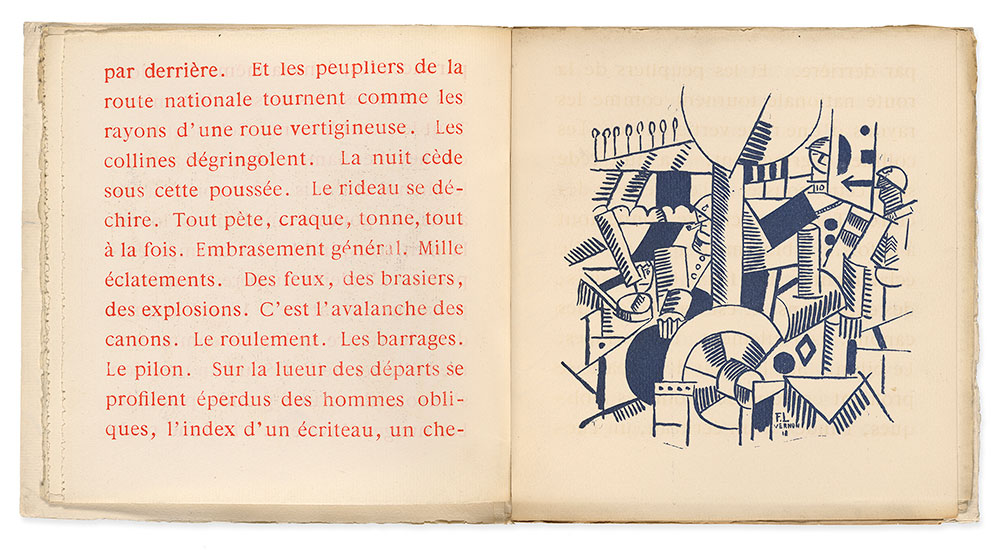

- Karl Kraus’s play The Last Days of Mankind. A satirical indictment of the glory of war. Kraus’s play enacts the tragic trajectory of the First World War, when mankind raced toward self-destruction by methods of modern warfare while extolling the glory and ignoring the horror of an allegedly “defensive” war. Bertolt Brecht hailed The Last Days as the masterpiece of Viennese modernism. In the apocalyptic drama Kraus constructs a textual collage, blending actual quotations from the Austrian army’s call to arms, people’s responses, political speeches, newspaper editorials, and a range of other sources. Seasoning the drama with comic invention and satirical verse, Kraus reveals how bungled diplomacy, greedy profiteers, Big Business complicity, gullible newsreaders, and, above all, the sloganizing of the press brought down the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

- A. Merritt’s “The People of the Pit.” Merritt’s yarn — an early example of “weird” fiction, which appeared in All-Story Weekly — destabilizes Enlightenment assumptions about the knowability of the universe, suggesting there are worlds here on Earth that lie beyond our understanding. Collected in Moskowitz’s Masterpieces of Science Fiction, the first time this often-reprinted story appeared in an sf anthology. Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2022. Will be reissued by MIT Press as part of the collection More Voices from the Radium Age.

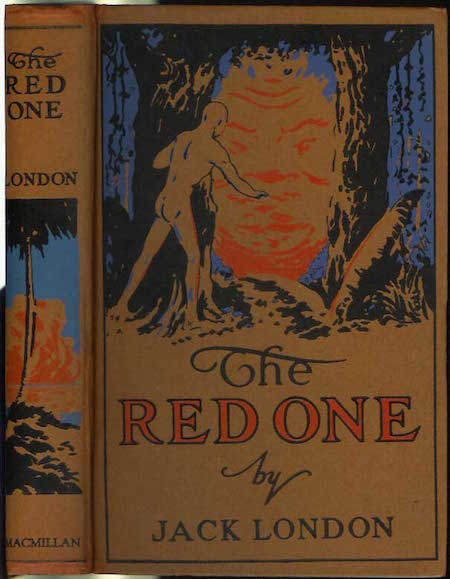

- Jack London’s “The Red One.” Lured into the uncharted jungle of Guadalcanal by an otherworldly noise, the naturalist Bassett is attacked by cannibalistic bushmen — who worship a deity known as “The Red One” (or “The Star-Born”). It’s a giant red sphere, which Bassett realizes is a message sent from an alien civilization — perhaps millennia ago — but which was lost, never to be discovered by western civilization. (“It was as if God’s Word had fallen into the muck mire of the abyss underlying the bottom of hell; as if Jehovah’s Commandments had been presented on carved stone to the monkeys of the monkey cage at the Zoo; as if the Sermon on the Mount had been preached in a roaring bedlam of lunatics.”) Will Bassett be able to carry news of this tremendous discovery out of the wilderness? Or will he be sacrificed to the Red One? Fun facts: First published posthumously, in the October 1918 issue of The Cosmopolitan; the story likely helped inspire Arthur C. Clarke’s The Sentinel — which inspired Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2012. Included in Voices from the Radium Age (MIT Press), a 2022 story collection edited by yours truly.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “Take it as Red.” R. Coutts Armour, who wrote prolifically as Coutts Brisbane (among other pseudonyms) was particularly good at bizarre alien life forms. His earliest known story is “Mixed Piggles” for The Red Magazine, 1 December 1910; in “Beyond the Orbit” (15 February 1914 Red Magazine) Mars is blown up by an Earthman; he prefigures Stanley G. Weinbaum in the creation of aliens both harmless and humorous. This is his fourth proto-sf story, as far as I can tell.

- Donovan Bayley’s “The Man Who Met Himself.” First appeared in the UK’s Red Magazine, reprinted in The Thrill Book. A man who, after an accident, frees his inner self. Is it sf?

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett) “Behind the Curtain.” This was a busy year for Stevens! “Behind the Curtain” appeared in the 21 September 1918 All-Story Weekly. A man’s obsession with an Egyptian sarcophagus and its dessicated occupant leads to an act of horrific revenge. Moskowitz says it is “superbly done.”

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s “Friend Island” — takes place in a gender-reversed future. In a future world where society is matriarchal, an old sailor tells a story of being shipwrecked on a strange, sentient tropical island which seems to want to cater to her every need. First appeared in All-Story Weekly. Serialized at HILOBROW in 2021.

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s The Citadel of Fear. A novel serialized in seven weekly installments in The Argosy (September 14–October 26). A Lost World tale — lost Mexican city with Aztec super-science. I think this is where Stevens gets her “dark fantasy” innovator rep.

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s “The Labyrinth” — appeared in three parts in All-Story Weekly. When Hildreth Wyndham’s cousin goes missing, he tracks down the man who abducted her. During a rescue attempt, however, things go horribly awry and an eclectic group of abductors, abductees, and rescuers find themselves trapped in a deadly and constantly shifting underground labyrinth constructed by a madman.

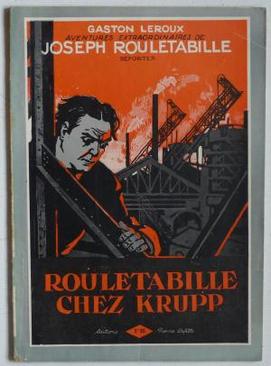

- Gaston Leroux’s Rouletabille chez Krupp (September 1917-March 1918), the last of the author’s otherwise nonfantastic tales to feature the reporter and adventurer Joseph Rouletabille. It’s a World War One thriller involving the invention of a super weapon.

- Homer Eon Flint’s “The Planeteer” (9 March 1918 All-Story Weekly). This is the prolific author’s first sf story, a remarkable work of interplanetary fiction. He was considered All-Story‘s best sf writer (by the editor). Moskowitz in Scientific Romance says this was a “different” novel, a cosmic concept that readers loved; it deals with sexual rivalry and personal ambition in an anti-Bellamistic society. Its sequel, “King of Conserve Island” (12 October 1918 All-Story Weekly), describes the corruption and collapse of a socialist society on Jupiter under the propaganda attacks of a reactionary, capitalist society. A good world wins through in the end.

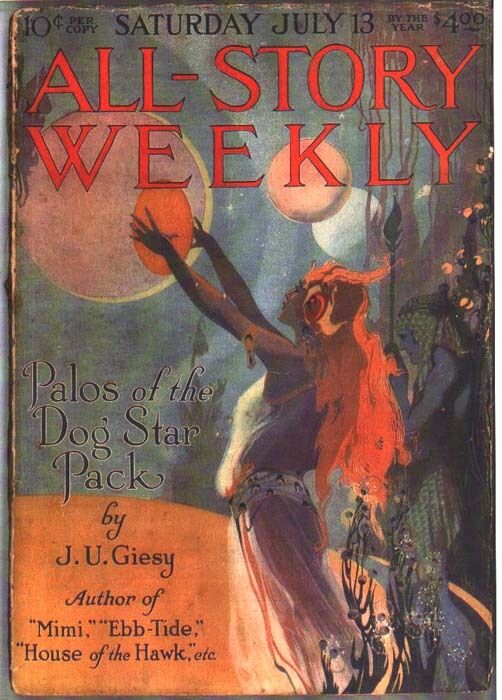

- J.U. Giesy’s Palos of the Dog Star Pack. Burroughsian fantasy — but also occult. Set on the planet Palos, the novel concerns Jason Croft, who has learned the art of astral projection. Croft feels an unusual calling to Sirius, the Dog Star, and projects his consciousness there, eventually finding his way to the major planet of the solar system, Palos. Once there, Croft finds human life, and floats among them observing their lives. He falls in love with the princess Naia, and determines to win her love. He eventually finds a host body in the form of a “spiritually sick” man. Within the man’s body, Croft sets out to win the love of the princess, by introducing technological improvements to the rulers of her kingdom. Because of the knowledge gained by astrally spying upon key figures and places on Palos, the people view him as an “angel” of sorts, sent by their deity Zitu. Moskowitz in Scientific Romance says this story is fascinating and well told. Sequels in 1919 and 1921.

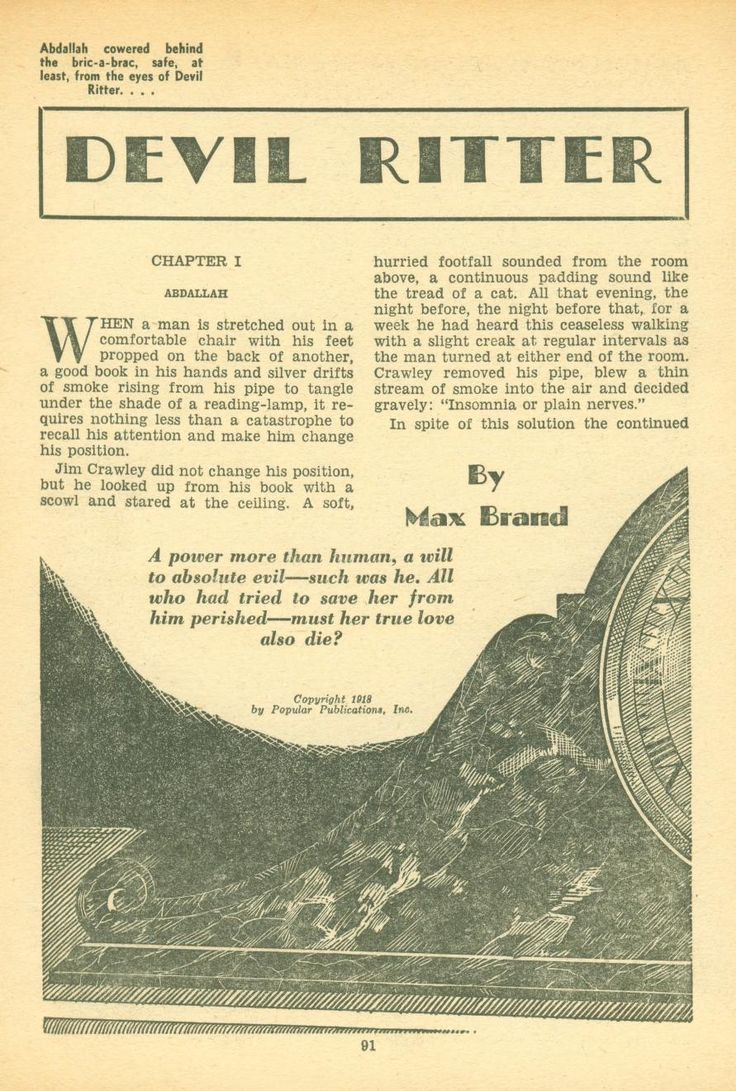

- Max Brand’s Devil Ritter. Brand was a famous writer of westerns. Moskowitz in Scientific Romance says this one — about a man who finds a telepath who can transmit to him all the impressions in the world (like Professor X’s Cerebro?) — is pretty good.

- Efim Zozulya’s The Doom of Principal City. A short novel. he giggle of the machine drives people crazy. Total surveillance. See Drozdz’s essay on “Parodies of Authority in the Soviet Anti-Utopias from 1918-1930.”

- Etbin Kristan’s Pertinčarjevo pomlajevanje (Pertničar’s Rejuvenation). Deals with unsuccessful attempts in creating the new race of men. Yugoslavian.

- Marie Corelli’s The Young Diana: An Experiment of the Future, about a scientific experiment to make a woman (and hence Woman in general) beautiful. A scientist develops a new rejuvenation technique that turns an older woman into a beautiful but completely heartless young woman. Subversive depiction of social norms. In 1922 it was adapted into an American silent film of the same title starring Marion Davies.

- Anna, comtesse de Brémont’s The Black Opal. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Lily McManus’s “The Professor in Ireland”, first serialised in the newspaper Sinn Fein. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

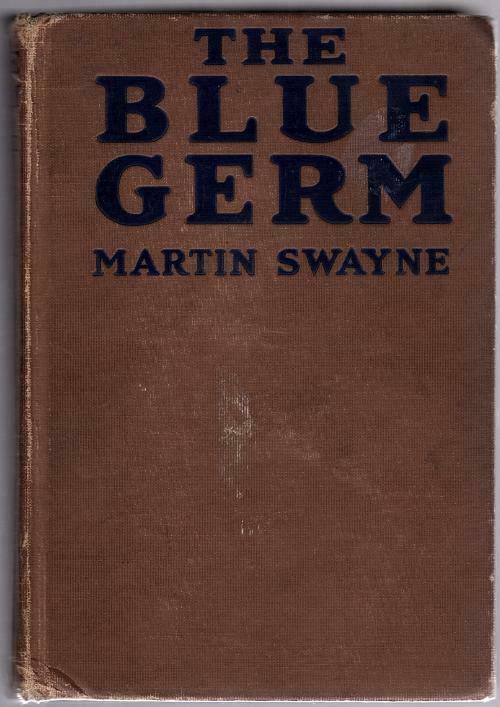

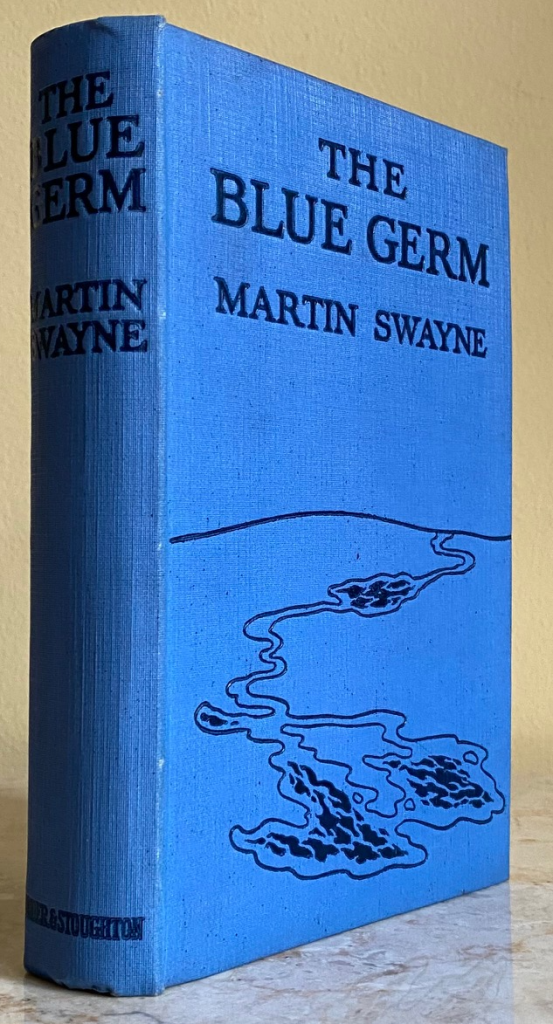

- Martin Swayne’s The Blue Germ. Inventive novel about an attempt to stop all human diseases, including aging, that is successful — but has some unattractive side effects. Martin Swayne was a pen name used by British psychiatrist (and noted Fourth Way teacher) Maurice Nicoll.It begins with a rural British doctor getting a marvelous revelation as he trips over his black cat, then making an abrupt visit to Russia. A strange and engaging tale with something deeper hiding in the silliness.

- George Allan England’s The Nebula of Death. Moskowitz calls it the most important piece of sf ever to run in The Popular Magazine.

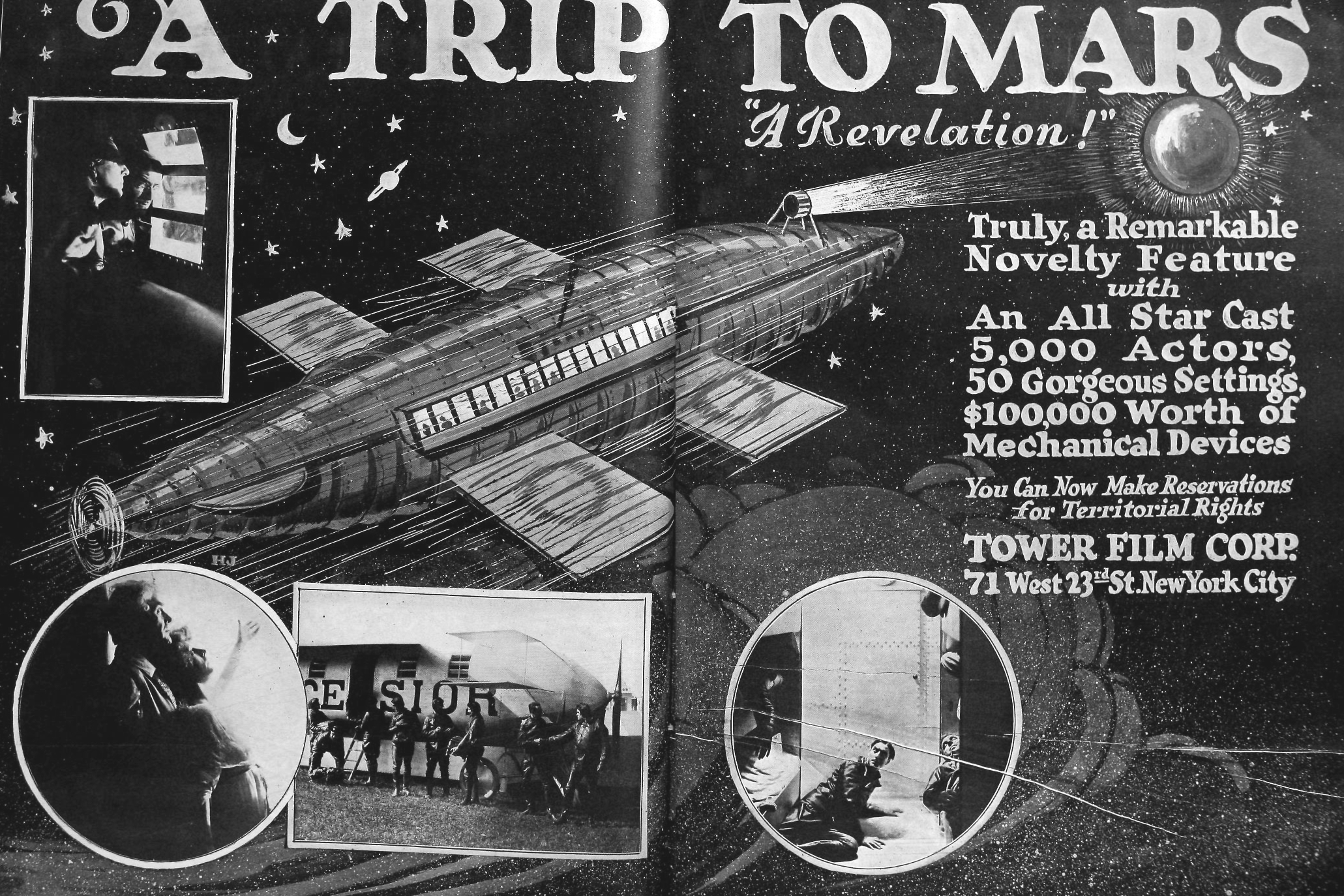

- Himmelskibet (akaExcelsior / A Trip to Mars / Das Himmelschiff) is a 1918 Danish film about a trip to Mars.

The artist’s “schadographs” are among the earliest intentionally abstract photographs. Using the cameraless photogram technique—in existence since the discovery of photography but previously unused for artistic purposes—Schad covered the surfaces of light-sensitive paper with various objects and then left them to develop by his windowsill. He preferred worn materials, such as scraps of paper and bits of fabric, often searching for these things on the streets and in garbage cans. Schad frequently extended his assault on artistic tradition by cutting a jagged border around the schadographs, “to free them,” as he explained, “from the convention of the square.”

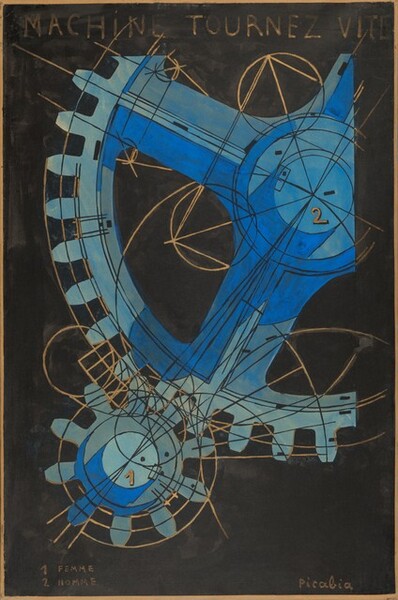

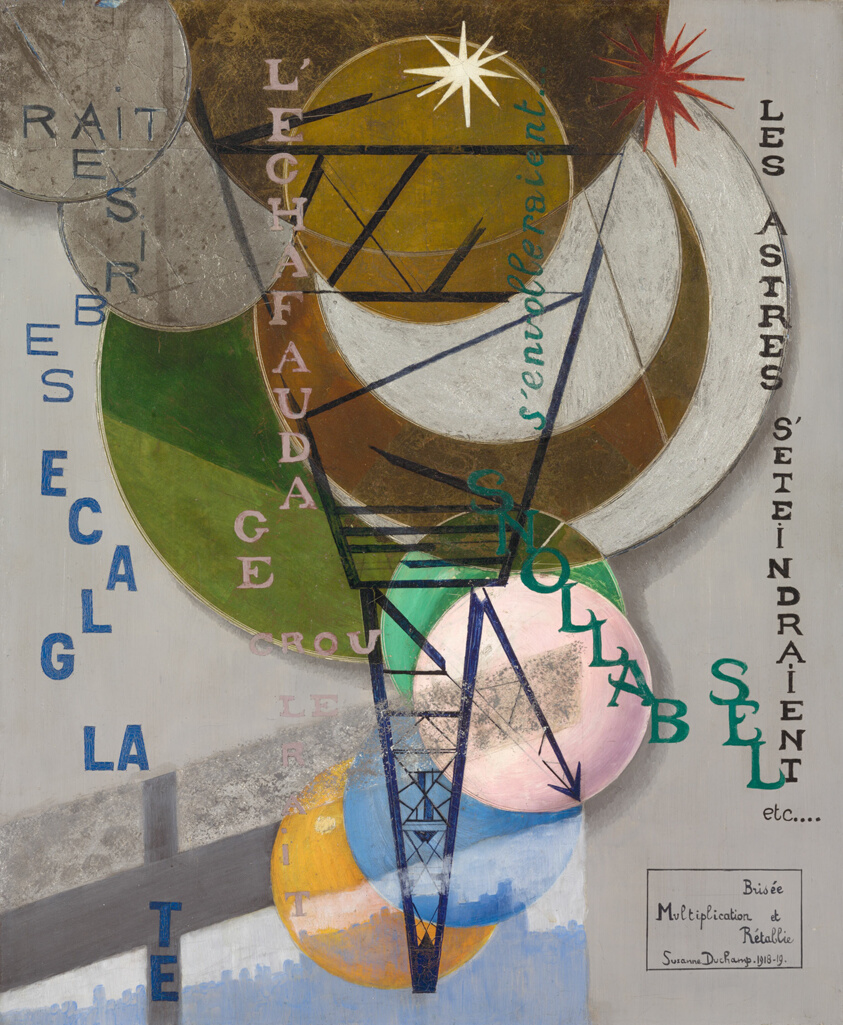

ALSO: Eddington’s Gravitation and the Principle of Relativity, Shapley discovers the true dimensions of the Milky Way. Emmy Noether theorizes the connection between symmetry and conservation laws. Constantinescu publishes Theory of sonics: a treatise on transmission of power by vibrations, originating the study of this branch of continuum mechanics. WWI rages — German offensive on the Western Front, Germans bomb Paris, Allied offensive on the Western Front opens, Allied conference at Versailles agrees on peace terms, German republic founded. “Spanish ‘flu” becomes worldwide influenza epidemic. British government abandons Home Rule for Ireland; Nicholas II and family executed; Rosa Luxemburg cofounds the German revolutionary Communist Workers’ Party; Eugene Debs imprisoned. Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians, US Post Office burns installments of Joyce’s Ulysses, Adams’ The Education of Henry Adams. Russell’s Mysticism and Logic. Kokoschka’s expressionist paintings, Miró’s first paintings. Tzara’s “Manifeste Dada 1918” proclaims that “Dada ne signifie rien”; Ball’s Flametti, or The Dandyism of the Poor fictionalizes the early days of Dada. Gasoline Alley strip first appears. Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party (Partito Politico Futurista) in early 1918, which was absorbed into Benito Mussolini’s Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919, making Marinetti one of the first members of the National Fascist Party.

Ernst Bloch’s Geist der Utopie (1918) (The Spirit of Utopia; republished in 1923). Bloch was influenced by Hegel and Marx (and by Karl May, author of popular adventure stories), as well as by apocalyptic and religious thinkers such as Thomas Müntzer, Paracelsus, and Jacob Böhme. He established friendships with György Lukács, Bertolt Brecht, Kurt Weill, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W. Adorno. His work — in particular, his magnum opus Das Prinzip Hoffnung (The Principle of Hope, 1938–1947) — focuses on an optimistic teleology of the history of mankind. In its biblical-Marxist-Expressionist style of thinking, Bloch’s Spirit of Utopia is a unique attempt to rethink the history of Western civilizations as a process of revolutionary disruptions and to reread the artworks, religions, and philosophies of this tradition as incentives to continue disrupting. For Bloch utopia is not just a subject for rational construction and projection into the future, but also something present in the now, although available only in glimpses or image-traces. Furthermore, these utopian image-traces are not necessarily wed to “progressive” politics. Indeed, one of Bloch’s most acute analyses of the utopian dimension concerns its function in the appeal of fascism, which is able to activate anti-capitalist imagery that works as an anticipation or prefiguration of utopia. Thus this reactionary movement appeals to longstanding popular traditions renounced by the overly rationalist left of the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries. By refusing to have any truck with “mystical” and “irrational” protests against the alienation and repressive rationalization of industrial capitalism, the left participated intellectually in the very same quantitative (and in its own way mystifying) logic as did its opponent, Capital, and ceded important terrain to the forces of reaction.

In 1918, Ouspensky separates from Gurdjieff, settling in England and teaching the Fourth Way in his own right.

T.S. Eliot in 1918: “A poet, like a scientist, is contributing toward the organic development of culture: it is just as absurd for him not to know the work of his predecessors or of men writing in other languages as it would be for a biologist to be ignorant of Mendel or De Vries.” (“Contemporanea,” The Egoist, 5/6, Jun.-Jul. 1918). Eliot also compared the critic to the scientist in The Egoist, 5/9 (Oct. 1918).

Writing in Der Stijl (1918), Georges Vantongerloo: “The great truth, or the absolute truth, makes itself visible to our mind through the invisible.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin