RADIUM AGE: 1935

By:

December 18, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

If we were to divide the Radium Age into quarters, 1935 would be the final year of its fourth quarter (1927-1935). How might we characterize this sub-era? Something for me to think about.

In my original formulation of the Radium Age, this era in the development of the sf genre ended in 1933. However, as noted above, eras don’t simply begin or end on a particular date… it’s a process. So I’ve extended my purview into the years 1934 and 1935 as well, seeking traces of the vanishing Radium Age even as sf’s so-called Golden Age begins to emerge.

Hugo Gernsback shifts away from sf to nonfiction, around this time — Wonder was failing; in November 1935 it started publishing bimonthly instead of monthly.

Let’s talk about what will happen in the world of pulp sf during the years immediately after 1935…

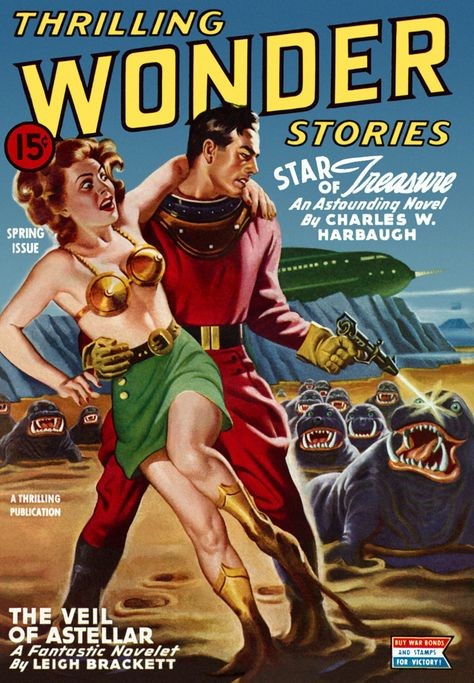

In 1936 Gernsback will sell Wonder to Beacon Publications, where, retitled Thrilling Wonder Stories, it will continue for nearly 20 years. This would mark the end of the Gernsback era in the pulps!

Between 1939 and 1941 there will be a boom in sf and fantasy magazines. Several publishers will enter the field, including Standard Magazines, with Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories (a retitling of Wonder Stories); Popular Publications, with Astonishing Stories and Super Science Stories; and Fiction House, with Planet Stories, which focused on melodramatic tales of interplanetary adventure. Also, Ziff-Davis will launch Fantastic Adventures, a fantasy companion to Amazing.

Astounding will extend its preeminence in the field during the post-1935 era. In 1937, John W. Campbell will become editor of Astounding. He will discover and/or employ Theodore Sturgeon, Lester del Rey, A.E. Van Vogt, Henry Kuttner, Robert Silverberg. L. Sprague de Camp; significant female writers such as Leigh Brackett and C.L. Moore; and the three most important writers who will help him shape the genre’s so-called Golden Age: Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and L. Ron Hubbard. Campbell will also launch Unknown, a fantasy companion to Astounding, in 1939; this will be the first serious competitor for Weird Tales, and it is now regarded as one of the most influential pulp magazines of the era.

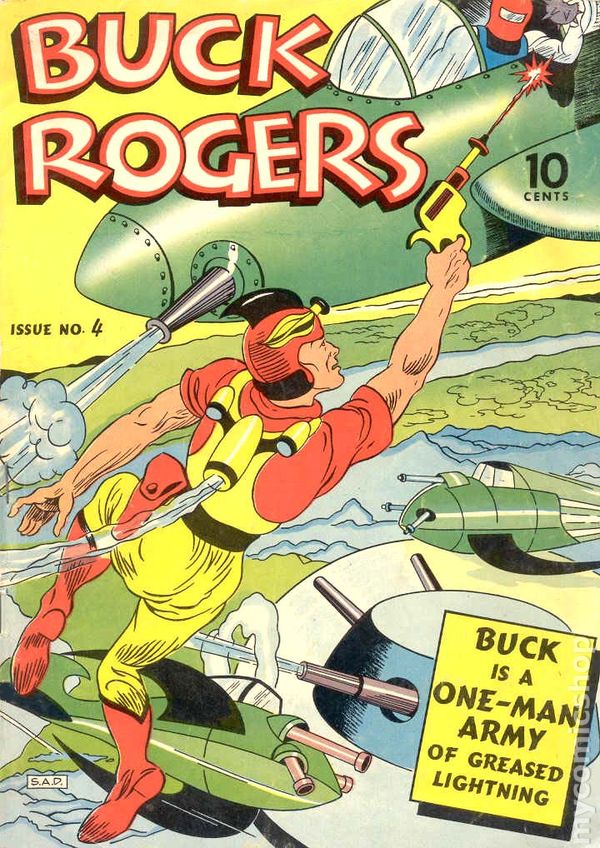

Why do I always call sf’s c. 1934–1963 period (note that I consider 1934–1935 an interregnum period) the “so-called” Golden Age? In part because that moniker was first used during this period, by sf writers and editors eager to distinguish what they were producing from the supposedly inferior proto-sf and sf of the twentieth century’s first decades — i.e., the era I’ve dubbed sf’s emergent Radium Age. I reject their characterization of pre-Golden Age sf as poorly written, naive, and immature “Buck Rogers” silliness (though this sort of thing was certainly popular during the Radium Age), so — even though I do admire and enjoy much “Golden Age” sf, I question the moniker.

Also! This golden idol, to quote Nebuchadnezzar, has feet of clay. Campbell’s “Golden Age” has a dark side: racist, misogynist, xenophobic, libertarian, anti-utopian. Let me immediately add that Radium Age proto-sf is very often also racist, sexist, and xenophobic; the MIT Press series of proto-sf reissues which I edit takes pains to point this stuff out. However, as I’ve noted elsewhere in this timeline series, Campbell and his cronies were influential in guiding the sf genre to mainstream success by redefining the genre in a restrictive way — systematically making it more difficult for women and people of color to publish sf. Since the Sixties the genre has struggled, with limited success until only quite recently, to overcome this “new normal.”

During the Campbell era pulp sf editors and readers alike would openly organize to purge the field of the “wrong” kind of fan and the “wrong” kind of writer.

Though he’d publish Leigh Brackett’s first stories, C.L. Moore’s best stories, Kate Wilhelm’s first story, and some other women sf writers, Campbell was a misogynist and abhored what he considered “feminine” aspects of pre-Golden Age sf. Leslie F. Stone, for example, would recall that Campbell rejected her story “Death Dallies Awhile” (it would appear in Weird Stories in June 1938) out of hand, stating that women had no place writing science fiction. See my notes in the 1926 installment on Susanne F. Bozwell’s research demonstrating that during the Golden Age, “editorial changes in the name of genre purity led to a steep decline in the publication of women in sf magazines.” Bozwell notes that in the early pulp period (c. 1926–1931, i.e., what I’d call Radium Age years), fifty-two women wrote for the pulps. Which wasn’t great! But during the Campbell era, it would get worse: From 1932–1939 (as sf’s Radium Age gave way to its so-called Golden Age), the number of women sf pulp authors would decrease sharply.

In the 1960s, Campbell would write in support of segregation (“Segregation,” 1963), call slavery “a useful educational system” and claim black writers did not or could not “write in open competition.” In a 1998 essay, “Racism and Science Fiction”, Samuel R. Delany would recall Campbell rejecting his novel Nova in 1967, saying in a telephone conversation with Delany’s agent that, though he had enjoyed the book, he did not feel his magazine’s readership “would be able to relate to a black main character.” All this was in addition to Campbell’s derogatory comments about women and homosexuality.

In her essay “Hitch Your Dragon to a Star” (in 1974’s Science Fiction: Today and Tomorrow) Anne McCaffrey — who began publishing work of genre interest in 1953 — recounts how she submitted a story to Campbell the protagonist of which was a “liberated woman.” Campbell wouldn’t have it: “Essentially, he told me, man still explores new territory and guards the hearth; woman minds that hearth whether or not she programs a computer to dust, cook, and rock the cradle.”

In their introduction to the 1995 anthology New Eves: Science Fiction About the Extraordinary Women of Today and Tomorrow, edited by Janrae Frank, Jean Stine & Forrest J Ackerman, the editors refer to the period between 1930 and 1950 as the era “when women were frozen out” of the sf pulps.

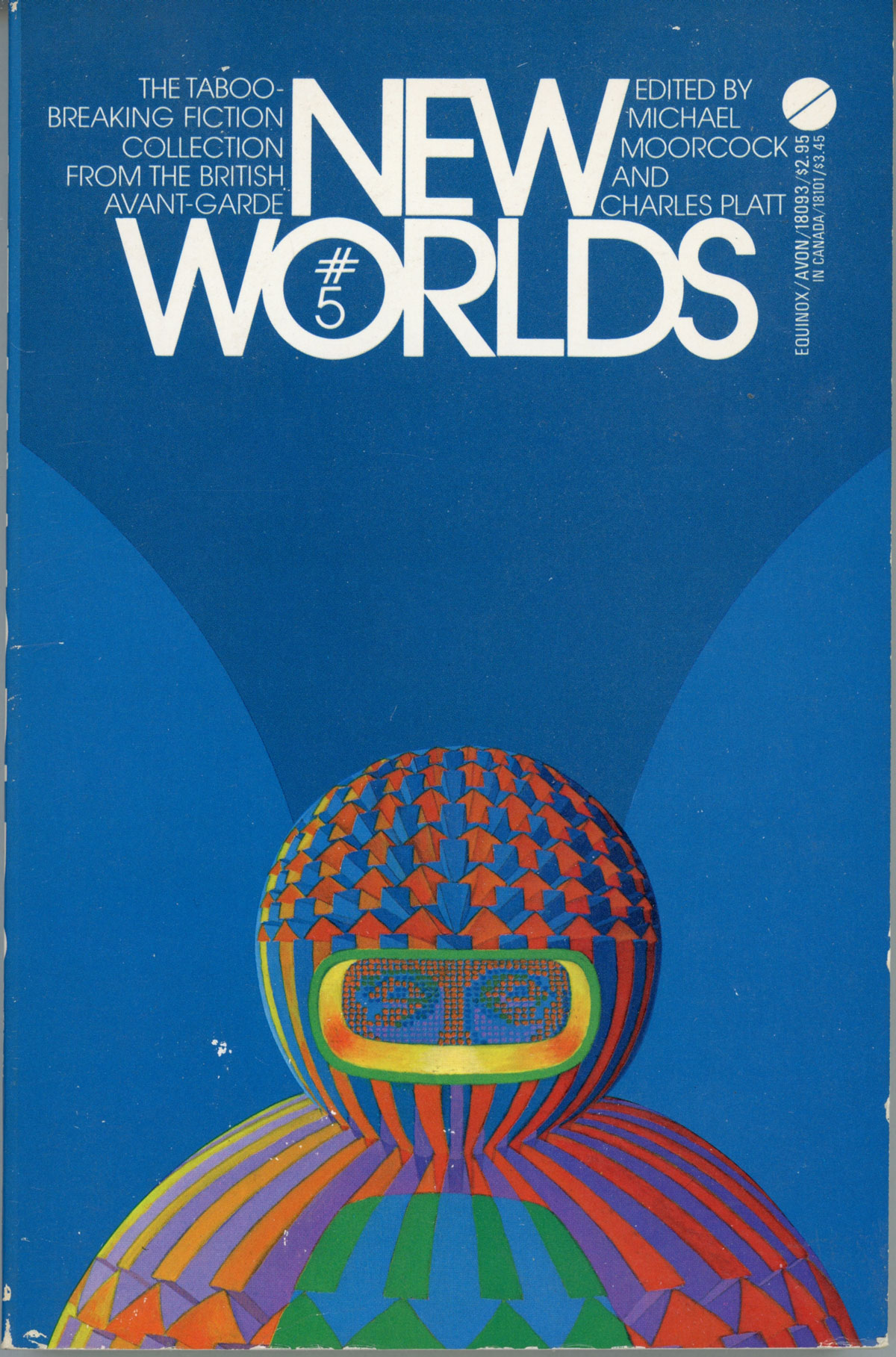

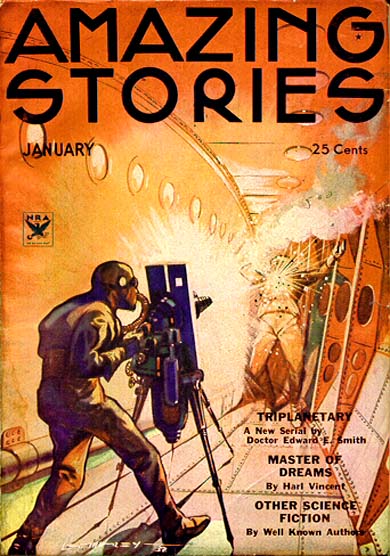

Michael Moorcock, who would succeed Campbell as sf’s great pulp magazine editor in the 1960s, would in a 1978 essay (whose title, “Starship Stormtroopers”, calls out Heinlein in particular as a kind of proto-fascist) critique the reactionary and conservative elements in sf and fantasy. He doesn’t let the Radium Age off the hook, either. American sf pulps of the 1930s (so: Radium Age and also Golden Age pulps) like Amazing Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories, he recalled, offered up “a good old-fashioned mixture of implicit racialism/militarism/nationalism/paternalism carried a few hundred years into the future or a few million light years into space.”

Moorcock would go on to recall:

John W. Campbell, who in the late thirties took over Astounding Science Fiction Stories and created what many believe to be a major revolution in the development of sf, was the chief creator of the school known to buffs as ‘Golden Age’ sf and written by the likes of Heinlein, Asimov and A.E. Van Vogt — wild-eyed paternalists to a man, fierce anti-socialists, whose work reflected the deep-seated conservatism of the majority of their readers, who saw a Bolshevik menace in every union meeting. They believed, in common with authoritarians everywhere, that radicals wanted to take over old-fashioned political power, turn the world into a uniform mass of ‘workers’ with themselves (the radicals) as commissars. They offered us such visions, when they attempted any overt discussion of politics at all. They were about as left-wing as The National Enquirer or The Saturday Evening Post (where their stories occasionally were to appear). They were xenophobic, smug and confident that the capitalist system would flourish throughout the universe, though they were, of course, against dictators and the worst sort of exploiters (no longer Jews but often still ‘aliens’). Rugged individualism was the most sophisticated political concept they could manage — in the pulp tradition, the Code of the West became the Code of the Space Frontier, and a spaceship captain had to do what a spaceship captain had to do… . By the early fifties Astounding had turned by almost anyone’s standard into a crypto-fascist deeply philistine magazine pretending to intellectualism and offering idealistic kids an ‘alternative’ that was, of course, no alternative at all.

The counter-“Golden Age” argument can’t really be articulated any better than that. Or can it? Fast-forward to 2019, when Jeannette Ng won Analog Science Fiction and Fact‘s John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. In her acceptance speech she called Campbell a “fascist.” Also: “He is responsible for setting a tone for science fiction that haunts this genre to this very day,” she said. “Stale, sterile, male, white, exalting in the ambitions of imperialists, colonialists, settlers and industrialists.” Thanks to Ng’s speech, the award has since been retitled the Astounding Award for Best New Writer. Ng said: “It’s a good move away from honoring a completely obnoxious man who kept a lot of people out of the genre, who kept a lot of people from writing, who shaped the genre to his own image.”

Cory Doctorow, a recipient of the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer as well as a recipient of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, publicly agreed with Ng, saying:

There’s plenty of evidence that Campbell’s views were odious and deplorable. It wasn’t just the story he had Heinlein expand into his terrible, racist, authoritarian, eugenics-inflected yellow peril novel Sixth Column. Nor was it Campbell’s decision to lean hard on Tom Godwin to kill the girl in “Cold Equations” in order to turn his story into a parable about the foolishness of women and the role of men in guiding them to accept the cold, hard facts of life.

It’s also that Campbell used his op-ed space in Astounding to cheer the murders of the Kent State 4. He attributed the Watts uprising to Black people’s latent desire to return to slavery. These were not artefacts of a less-englightened era. By the standards of his day, Campbell was a font of terrible ideas, from his early support of fringe religion and psychic phenomena to his views on women and racialized people.

Longtime sf reviewer and anthologist Rich Horton chimed in, too:

I think Campbell did tremendous good for the field, in a number of ways — insisting on better prose, better story construction, promoting a fruitful formula for using scientific speculation as a way to generate story ideas, and truly supporting new writers (yes, white men mostly), and truly helping them improve. (And that’s the rationale for naming the Campbell Award after him.) But he did lots of harm, too. Many have pointed out that he endorsed a colonialist view of the human future in space, and insisted on human superiority. And this is to a great extent true (though you can find plenty of counterexamples in Astounding.) He supported a lot of really stupid pseudo-scientific ideas, aside from his pernicious racial views, and especially in the last couple of decades of his time at Astounding/Analog these hobbyhorses of his contributed to a real decline in the magazine’s quality (indeed — it did become pretty sterile eventually). These ideas went way beyond the most famous and probably worst of them (Dianetics/Scientology) — he was also at times obsessed with the Dean Drive, with dowsing, with psi, with something called the Hieronymous Machine — and he wanted his writers to write stories with those ideas at the core.

Responding to Ng’s use of the term “fascist,” John Scalzi agrees: “Go have a deep dive into some of the things Campbell believed and espoused; the Venn diagram for ‘Things Campbell Said’ and ‘Things Fascists Say’ is, uhhhhh, overlappy.”

So yeah — that’s why I question the moniker “Golden Age.” I agree with Horton that sf did “mature” in terms of prose quality, overall, during this era; but… we should be very skeptical of the rhetoric of “maturity,” via which racist, misogynist, anti-socialist and other toxic ideologies are smuggled into our set of assumptions about sf. The era’s virtues and vices are thoroughly imbricated, impossible to untangle; the same goes for the virtues and vices of its authors. But we can at least expose the vices.

One could go on about this topic, but I’ll stop here. I also make a few remarks about this sort of thing in this Q&A.

PS: Frederik Pohl once wrote, “I was not part of the Campbell revolution. I was in the opposing camp. In fact, John Campbell and I were competitors. By the fall of 1939, when I was nineteen years old, I had discovered how to be sure there was at least one science-fiction editor who would look with favor on my stories: I became one.” I’d like to know more about this opposing camp!

Only eight science-fiction and fantasy magazines would survive World War II. Very few science-fiction or fantasy pulps were launched after this date; the 1950s was the beginning of the era of digest magazines, though the leading pulps continued until the mid-1950s. Sf authors would stop selling to pulps, and move instead to mainstream magazines and large book publishers.

Copyrighted works from 1935 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2031. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

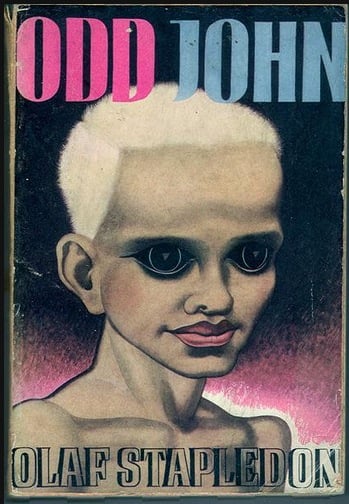

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1935, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: BLAST RIFLE | GRAVITIC | HOMO SUPERIOR (in Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John) | ION GUN | SAPIENT | SCANNER | SPACE WARP | TERRAN | VIEWPORT.

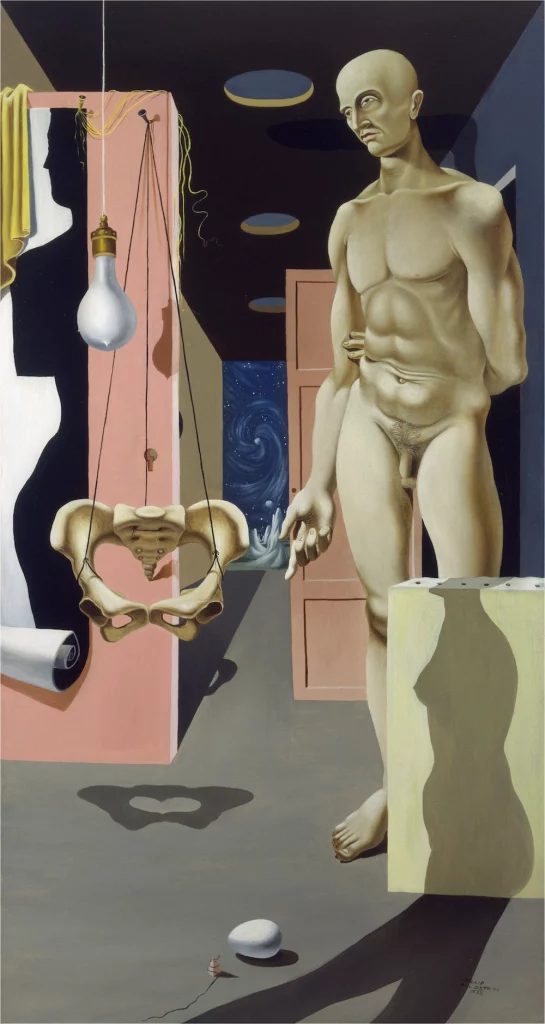

- Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John (1935). An extraordinary novel — by a visionary author who helped usher in Radium Age-era sci-fi themes and memes into the genre’s so-called Golden Age — which deserves to be much better known. Led by a teenage mutant “supernormal,” Odd John, a group of evolved misfits form an island colony. There, they experiment with telepathic communication, free love, “intelligent worship,” and “individualistic communism.” The jacket illustration shown here captures Stapledon’s notion of the titular John: half-child and half-philosopher, ruthless but not malicious, “a creature which appeared as urchin but also as sage, as imp but also as infant deity,” a fallen angel with a face that is “half monkey, half gargoyle, yet wholly urchin, with its huge cat’s eyes, its flat little nose, its teasing lips.” Cue David Bowie: “Look at your children/See their faces in golden rays/Don’t kid yourself they belong to you/They’re the start of a coming race.” The novel’s narrator, who has observed John growing up, and who is the only un-evolved human permitted to visit the island, isn’t sure whether to be overjoyed or terrified about what the “wide-awakes” are planning. Fun fact: Matthew De Abaitua’s terrific 2015 sci-fi novel If Then is, in certain key respects, an example of Stapledon fanfic… complete with a WWI-era homo superior known as Omega John.

- Herbert Read’s The Green Child. M.R. Sauter once enthused about this book, here at HILOBROW, under the auspices of a series on 1930s fantasy. It’s a philosophical novel that could perhaps best be described as science fantasy. A philosophical novel whose hero, having grown disenchanted with the imperfections of the quasi-utopian state which he has established in South America, returns to England where he discovers a mysterious green child and a truly utopian mode of existence. “A remarkable double utopia in which two visions of ideal human life — one a Latin-American political utopia, the other a mystical, underground realm in which human aspirations are transcended — mirror one another, comprising together a critique and dramatic metaphor of the utopian impulse as a whole.” – Clute and Nicholls (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

- Nelson Bond’s “The Monster from Nowhere” — a fourth dimensional creature — a likely source of inspiration for Pynchon’s Against the Day.

- Régis Messac’s Quinzinzinzili. At the time of World War II, a Japanese scientist develops a chemical reaction that combines the oxygen and nitrogen in the atmosphere. The air becomes unbreathable for the majority of species, and humanity is swept with mass extinction. Ten children left in a deep cave survive and find the purified Earth. The man who accompanies them, their tutor, witnesses the creation of a new humanity — whose new god they call Quinzinzinzili. Messac was in active service throughout World War One, where his pacifism was confirmed; his later Communist affiliations presumably occasioned his deportation in 1943 by the German government and incarceration in various camps until his death, probably in January 1945, in the Gross-Rosen complex, or Dora, or Bergen-Belsen.

- Hemendrakumar Roy’s Amaanushik Maanush (The Inhumans). More info on this Bangla-language novel to come.

- Jacques Spitz’s L’agonie du globe (1935; trans Margaret Mitchiner as Sever the Earth 1936), describes the consequences attendant upon a geological disaster which splits the planet into two halves. The portion containing America soon collides with the Moon; there are no survivors. Spitz has been called perhaps the central French sf author of the 1930s/1940s.

- Alan Hyder’s Vampires Overhead. Apocalyptic horror thriller in which alien vampires come to earth via comet, and devastate civilization. Anticipates Colin Wilson’s THE SPACE VAMPIRES by 40-odd years. “Told with very considerable vigor.” — Clute and Nicholls.

- James Corbett’s Devil-Man from Mars. Antiwar SF thriller heavily influenced by the works of Wells. Mars is a peaceful utopian world state; the humanoid Martians are seven-foot tall advanced super-beings who live in the nude in harmony with nature. The story includes Corbett’s mind control, a “Propulsive Ray,” and a “Death Ray,” the latter to be used on Earth to enforce world peace. Not a good book. But it seems oddly similar to Stranger in a Strange Land, to me.

- Maurice Dix’s The Golden Fluid. An Oriental cadre of secret masters aspire to immortality through imbibing an elixir of unknown provenance, and by using advanced technology to preserve themselves. They threaten the world, but are defeated in the end.

- M.P. Shiel’s The Invisible Voices. The fifth and last book of Shiel stories issued during his lifetime. Mixed collection of eleven short stories in a frame narrative, several of which are fantasy and sf, including the excellent visionary fantasy, “The Place of Pain.”

- Lilith Lorraine’s “The Celestial Visitor” (Wonder Stories) and “The Isle of Madness” (Wonder Stories). LL is one of at least five pseudonyms of Mary Maude Wright (1894-1967), US poet, editor, radio lecturer and author, who regularly published sf in the 1930s pulps. Her favourite themes include classless societies and revised gender roles. In the first story, we learn that as Atlantis was dying, some Atlanteans escaped to another planet and established a perfect civilization. One day, far in the future, a bored member of this race discovers its terrestrial origins and journeys back to earth, where he is jailed, heralded by a journalist, and falls in love with a judge’s daughter. (This also reminds me of Stranger in a Strange Land; see the JAmes Corbett novel above.) The second story concerns America in 1940; the country has turned fascistic, and is devoted to a religion that combines materialism and violence, overseen by a mechanical mind. Those who resist the conformity are exiled to the “Isle of Madness.” There, over generations, they develop super-sciences and come into telepathic contact with some kind of human master soul. In time, the soul tells them to spread out across the world, where they see humankind has collapsed into wolf-like creatures and civilization is no more.

- G. Cornwallis-West’s The Woman Who Stopped War. Suggested to me by Susan Grayzel. Novel of the near future and of a women’s pacifist movement in Britain to avert war. Mary Sarn – who has already lost her lover in World War One – sacrifices her virtue to a war-friendly man of wealth in order to gain money to fund the Women’s Save the Race League as another conflict threatens. War is halted. But was it worth the cost? The author (1874-1951) was as well known for his marriages as for his fiction, his first being to Jennie Churchill, mother of Sir Winston Churchill, whom he deserted for Mrs Patrick Campbell as she was about to star in the London premiere of Shaw’s Pygmalion in 1914, and whom he deserted in turn.

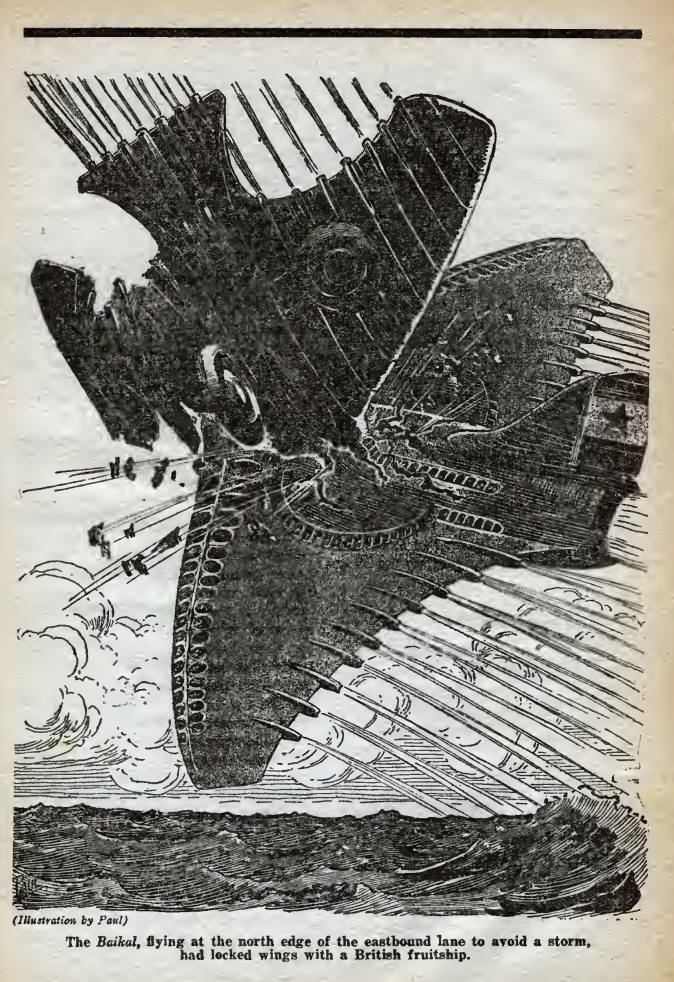

- Frank Dubruz Fawcett’s (as by Simpson Stokes) Air-Gods’ Parade. Suggested to me by Susan Grayzel. Assembles Future War tales, usually involving aviation, with a slight hint of the Pax Aeronautica.

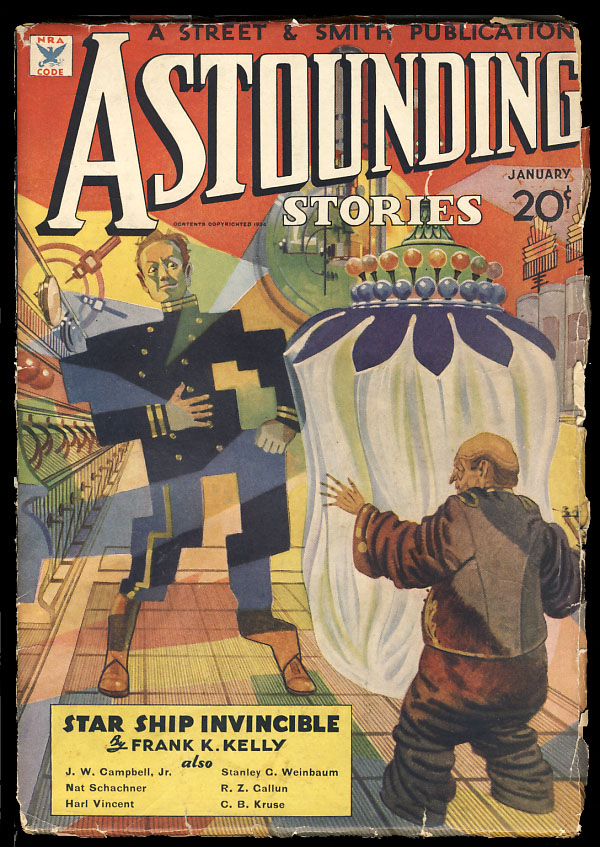

- Ross Rocklynne’s “Man of Iron” (Astounding). Ross Rocklynne was the working name of US author Ross Louis Rocklin (1913-1988) for his sf stories, most of which appeared in such magazines as Astounding from the mid-1930s up to 1947, beginning with “Man of Iron.” He specialized in space-opera plots constructed around sometimes ingenious “scientific” problems.

- Laurence Manning’s “Seeds from Space.” The culmination of his Stranger Club sequence, which began with “The Call of the Mech-Men” (November 1933 Wonder Stories). Ashley’s Time Machines says it’s very good.

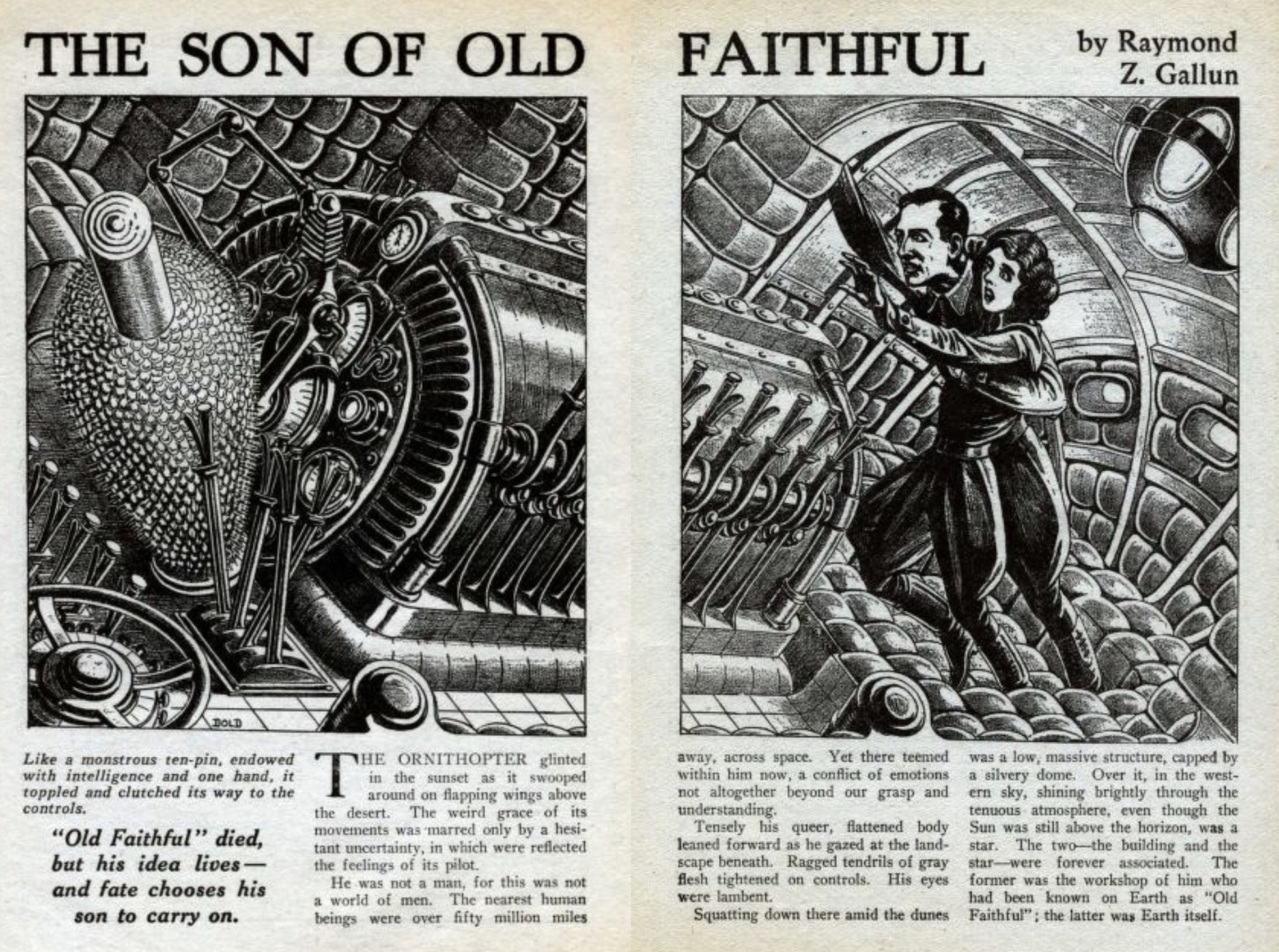

- Raymond Z. Gallun’s “Son of Old Faithful.” Sequel to “Old Faithful.” Fun fact: This seems to be the first time “The Son of” title concept was used in a sf magazine.

- Laurence Manning’s World of the Mist (Wonder, September 1935). Short novel exploring another dimension — Ashley says it’s good.

- Algernon Blackwood’s “Elsewhere and Otherwise” (in the collection Shocks). A strange short story about a man who somehow transcends space and time, returning briefly to pay back a debt. Blackwood’s belief in other dimensions, or “higher space”, as he called them, fuels several of his later stories. He enjoyed the phrase “elsewhere and otherwise”, believing that people might slip through into a higher dimension and either reappear at a great distance, as in the later John Silence story “A Victim of Higher Space” (December 1914) and “The Man Who Was Milligan” (November 1923), or be trapped in higher space, aware of our plane of existence but unable to make contact, as in “Elsewhere and Otherwise.”

- Axel Klinckowström’s Skräck över norden [“Terror in the North”]. Swedish dystopia by zoologist, prolific author and explorer Axel Klinckowström (1867-1936). Rapid climate change creates a new glacial period during which modern Scandinavian society is destroyed.

- C.L. Moore’s “Julhi” (Weird Tales, March 1935). A Northwest Smith adventure. Northwest takes a wrong turn in the ruins of Vonng, Venus.

- C.L. Moore’s “Nymph of Darkness” (Fantasy Magazine fanzine, April 1935; written with Forrest J. Ackerman). A Northwest Smith adventure.

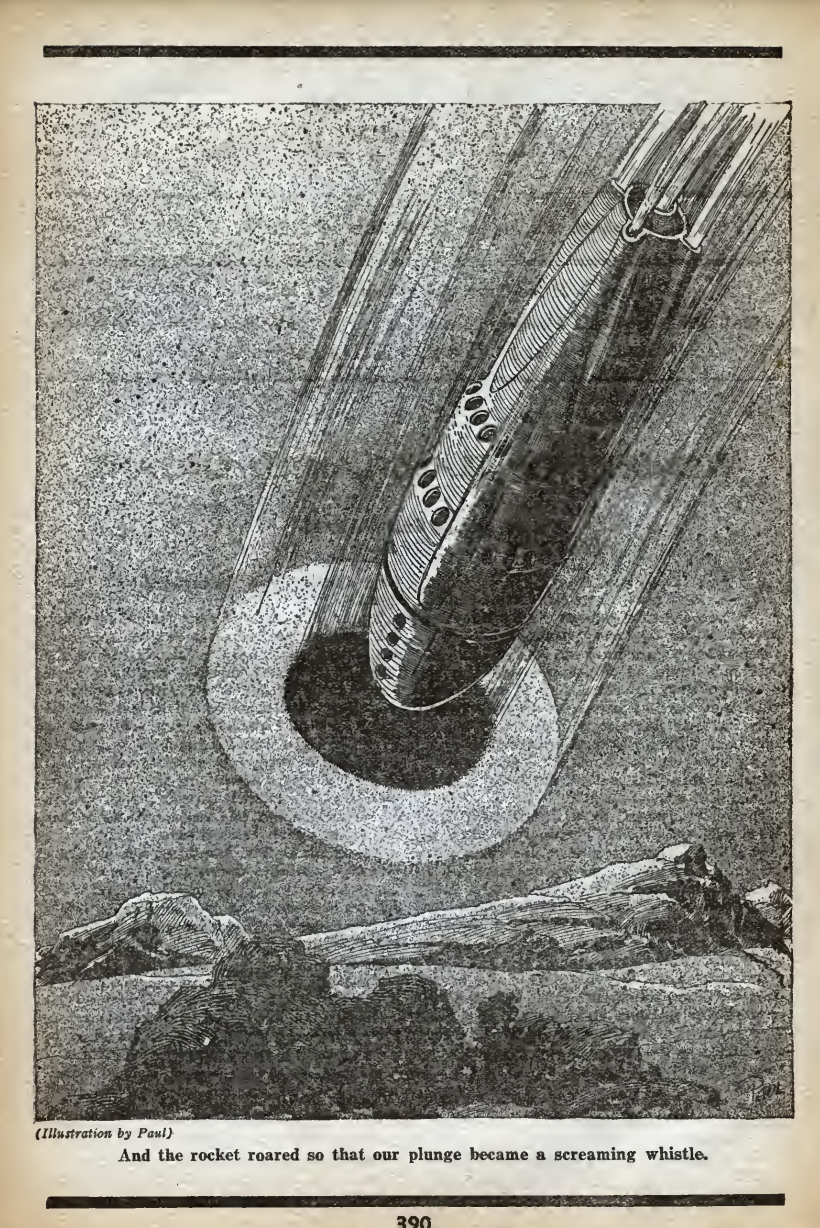

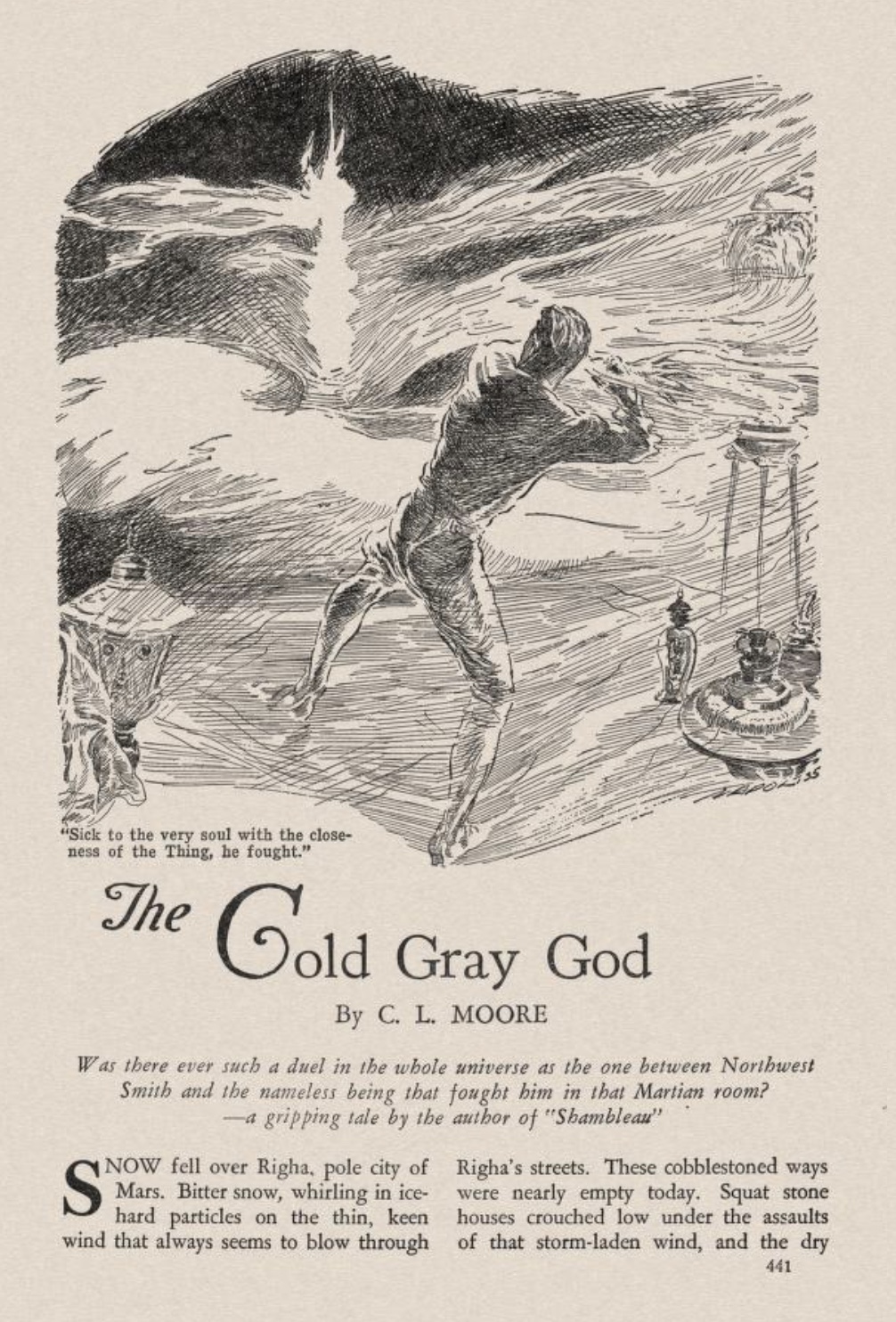

- C.L. Moore’s “The Cold Gray God” (Weird Tales, October 1935). A Northwest Smith adventure. In the polar city of Righa on Mars, Northwest meets a Venusian lady who isn’t quite herself. Judai is a standard noir Lady in Red, an old flame, and a glamorous idol singer once thought to be missing. And, like all of Smith’s sudden flames, she is hopelessly doomed. By the time she returns to Northwest’s life, she is little more than a skinsuit for something unseen. All the little familiarities known between old partners are now wrong, enough to tip off the usually obtuse Smith. But the sheer memory of the beauty of the woman who was Judai causes Smith to investigate. The being occupying Judai has its eye on Northwest Smith as its next skinsuit, and the artifact Smith recovers is key to let it jump from one body to the next. Smith spends the last half of the tale fighting to keep control of his body and his mind from something more ancient and deadly than the Shambleau who almost devoured him. That something wants to use him to unlock the door for an even greater evil.

- C.L. Moore’s “Jirel Meets Magic” (July 1935 Weird Tales). A Jirel of Joiry adventure. Begins in medias res, as Jirel is leading a charge over the drawbridge of a castle that protects the sorcerer, Giraud. She ends up venturing into a peculiar woodland beyond a magic window – finding equally peculiar people and things there. It’s a Narnia-ish fantasy story, I guess, unless we think of the door as an sf dimensional portal.

- Claude Houghton’s This Was Ivor Trent. Arguably science fiction, since it looks at a writer who has a vision of the future. Houghton declared that his work was substantially based on the thesis that modern civilization must collapse “because it no longer believes it has a destiny”; thus his novels of ideas occasionally stray into the surreal, the supernatural or sf. Houghton comes closest to the full Scientific Romance in this novel, which examines the effect upon a writer of a vision of human evolution in which he is communicated with by a man of the future, confirming in Trent a mysterious ability to influence his fellows. But this power is insufficient to stay the omnipresent dread felt by the cast — and indeed by most of Houghton’s characters — a dread specifically associated with the aftermath of the previous war and premonitions of World War Two.

- Clifford D. Simak’s “The Creator.” Novelette in Marvel Tales of Science and Fantasy (March-April 1935). Suggests that our universe was not created by God.

- Donald MacPherson’s Go Home, Unicorn. Pseudonym of UK psychologist George Humphrey (1889-1966) who held various academic posts in Canada and the USA and later became professor of psychology at Oxford. A Scientific Romance set in Montreal, in which the life of a research scientist — loved by two women, one jealous — is much confused by projections, into the world of matter, of their (and other people’s) mental fantasies, brought into being by the X-ray field he is using to create mutations (in guinea-pigs; there is much scientific speculation, rather far-fetched, about the nature of the mind/matter division. The sequel, Men Are Like Animals (1937), features the same research scientist Reggie Brooks, and involves a device that controls thoughts.

- Fenner Brockway’s Purple Plague: A Tale of Love and Revolution (1935), in which a passenger liner is quarantined for a decade because of a plague. A new egalitarian society emerges; there is much opportunity for satire.

- George Schuyler’s “The Ethiopian Murder Mystery” (5 October 1935-? February 1936 Pittsburgh Courier). A series of murders leads to the discovery of an Italian plot to prevent the Ethiopian government from obtaining a newly invented Death Ray.

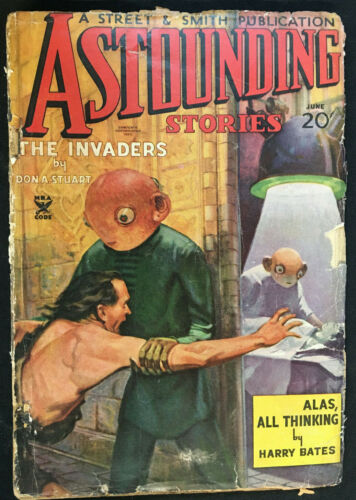

- Harry Bates’s “Alas, All Thinking!” (June 1935 Astounding). A novelette. Explores the idea that technological progress might produce degeneration in human beings. Bates was founding editor of Astounding Stories, January 1930-March 1933. Bates contributed stories to Astounding in collaboration with his assistant editor, Desmond W Hall, the two sometimes writing together as H B Winter but more famously as Anthony Gilmore, under which name they produced the popular Hawk Carse series. (His 1940 story “Farewell to the Master” would be adapted as The Day the Earth Stood Still.) He wrote “Alas, All Thinking!” under his own name. Fun fact: In “Will the Atomic Bomb Ever Be Perfected?” Philip K. Dick would write that “Out of the SF that I have read, one story means more to me than many others. It is Harry Bates’s “Alas, All Thinking.” It is the beginning and the end of of literate science fiction. Alas.”

- John W. Campbell (as Don A. Stuart)’s “Night” (Astounding Stories, October 1935). An intriguing sequel to “Twilight” — shows how machines continue to survive long after humans. Scott Bradfield calls this one of Campbell’s breakthrough stories “that testify to a young author’s sense of isolation and helplessness in the face of immeasurable universal forces.”

- John W. Campbell (as Don A. Stuart)’s “The Machine” (1935, Astounding). Part of the Machine Trilogy. Ashley’s Time Machines describes it as a super-computer realizing its constant vigil over humans will ultimately harm them. AI — artificial intelligence./li>

- John W. Campbell’s “The Invaders” (1935, Astounding as by Stuart).

- John W. Campbell’s “Rebellion.”

- John Wyndham (John Beynon Harris)’s The Secret People. First novel? serialized in The Passing Show.

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “Pygmalion’s Spectacles” — prophetic treatment of virtual reality.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Dark Age” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1938).

- Festus Pragnell’s “The Green Man of Graypec” (July-September 1935 Wonder Stories), published in 1936 as The Green Man of Kilsona, and then in revised form in 1950 as The Green Man of Graypec. Describes a voyage into a miniature world where the inhabited planet of Kilsona is discovered. Pragnell (Frank William Pragnell) was a UK police constable (!), clerk and author.

- Katharine Burdekin’s [“Murray Constantine”] The End of This Day’s Business. Written 1935, published by The Feminist Press, 1989. Utopia written in 1930s, by a feminist, not published for 50 years. In a world ruled by women, men live alone and rear boys in a cheerful atmosphere of sports, physical labor, and healthy sexuality, but without the consciousness of anxiety of knowledge of history claimed by women. It is the 63rd century and women have long established their ascendancy, having sickened of the world wars that men wage. Males are raised in careful ignorance of the past; literature exists only in Latin, a language of which men are not even aware. Men here hate their bodies, suffer profound insecurity, cannot fulfill themselves. Grania, a distinguished philosopher, perceives the harm of sexism and risks her life to educate her son. As Pygmalion, her dogged lessons concentrate heavily on the flawed political and social structures of our times, here called the Childhood Age, and on the particular horrors of fascism and Hitler. This novel, described by Choice as “a forgotten masterpiece,” turns on the desire of a woman to teach her son about the past. Burdekin’s (1896-1963) companion, a woman who requests anonymity, has stated that the English feminist “never… took longer than six weeks in writing any book.” So it is not surprising that this previously unpublished 1935 novel almost wholly neglects literary craft in favor of the author’s political agenda. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Hazel Heald’s “Out of the Eons,” in Weird Tales, April 1935. I think this is fantasy, not sf. Several members of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos are mentioned in this story. Hazel Heald (1896 – 1961) was a pulp fiction writer, who lived in Somerville, Massachusetts. She is perhaps best known for collaborating with Lovecraft. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- March Cost (Margaret Mackie Morrison)’s The Dark Glass. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

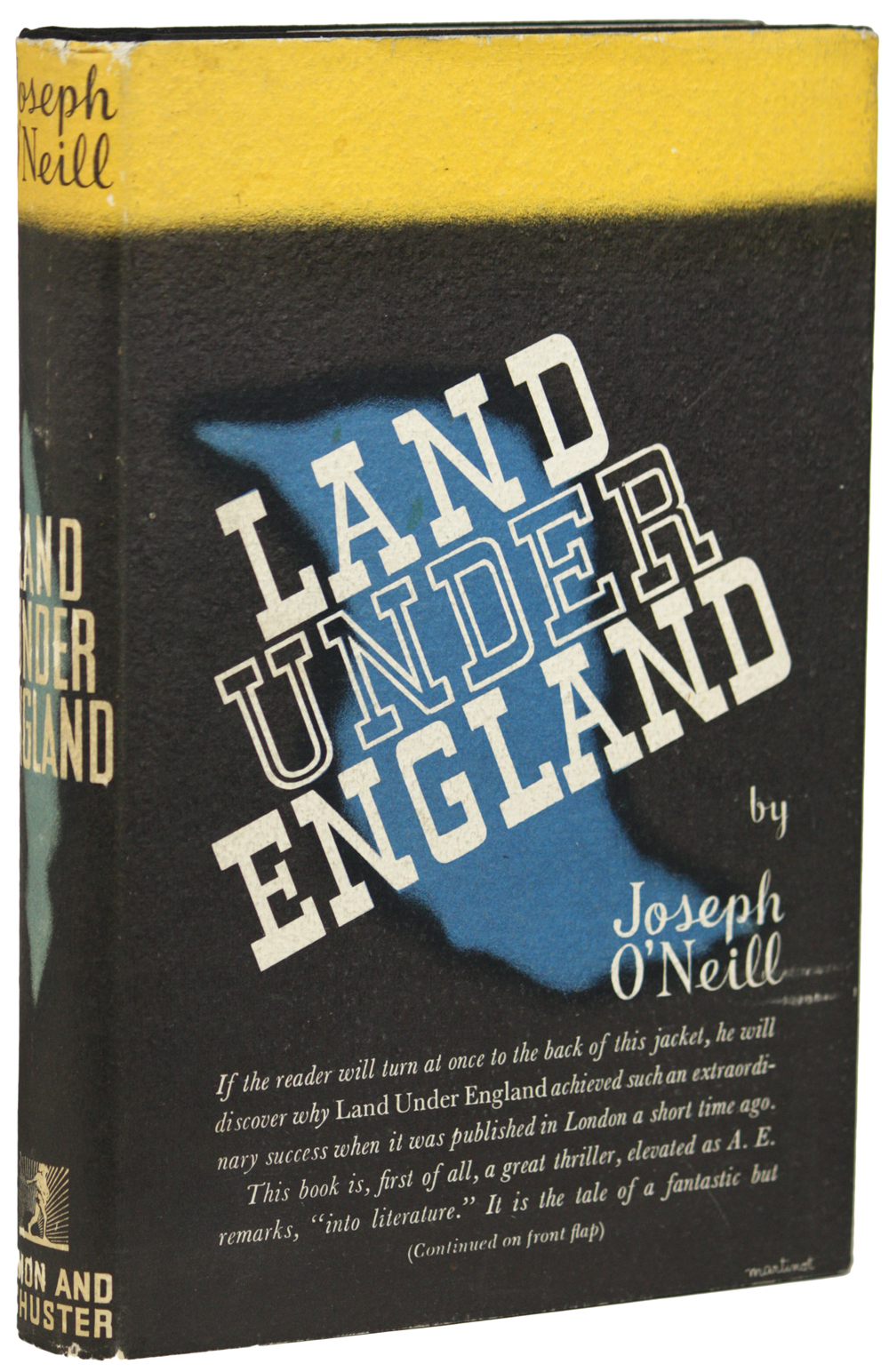

- Joseph O’Neill’s Land Under England. A stylish political allegory about totalitarianism and thought control. A terrifying journey into the earth’s interior. The protagonist refuses to join the rigidly controlled society of the interior world’s inhabitants and must find a route to the surface or perish. “A totalitarian utopia where little individual emotions are absorbed by the love for the common good. There are only two classes: the leaders and the robotlike citizens, whose minds have been ‘rearranged.'” – Gerber, Utopian Fantasy

- Leslie F. Stone’s “The Man with the Four Dimensional Eyes” (Wonder Stories, August 1935). Relative perspective.

- Leslie F. Stone’s “Cosmic Joke” (Wonder Stories, January 1935). Inspired by her young son. Stone would slow down after 1935, publishing just one story per year.

- Leslie F. Stone’s “When the Flame-Flowers Blossomed” (Weird Tales, November 1935).

- Leslie F. Stone’s “The Fall of Mercury” (Amazing Stories, December 1935).

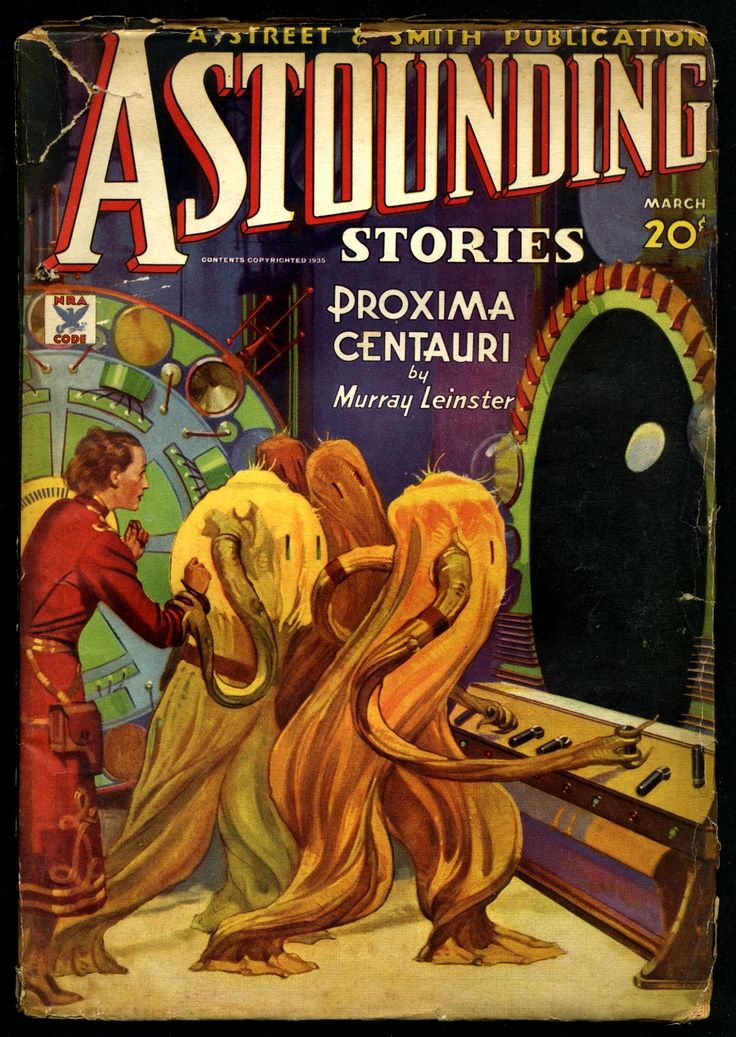

- Murray Leinster’s “Proxima Centauri.” The first of Leinster’s many space operas. Leinster prefigures the “generation starship” theme in “Proxima Centauri” (March 1935 Astounding), whose spherical starship makes the relatively modest journey from Earth to Proxima Centauri in seven years, but is crewed with families who produce more children en route: it is noted that “not only could the mighty ship subsist her crew forever, but that the crew itself […] could so far perpetuate itself as to make a voyage of a thousand years”. (Also anticipating later treatments, there is a revolt of crew against officers.) Leinster published some remarkably inventive and clear-sighted stories in the mid-1930s. Reprinted in Road to Science Fiction. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

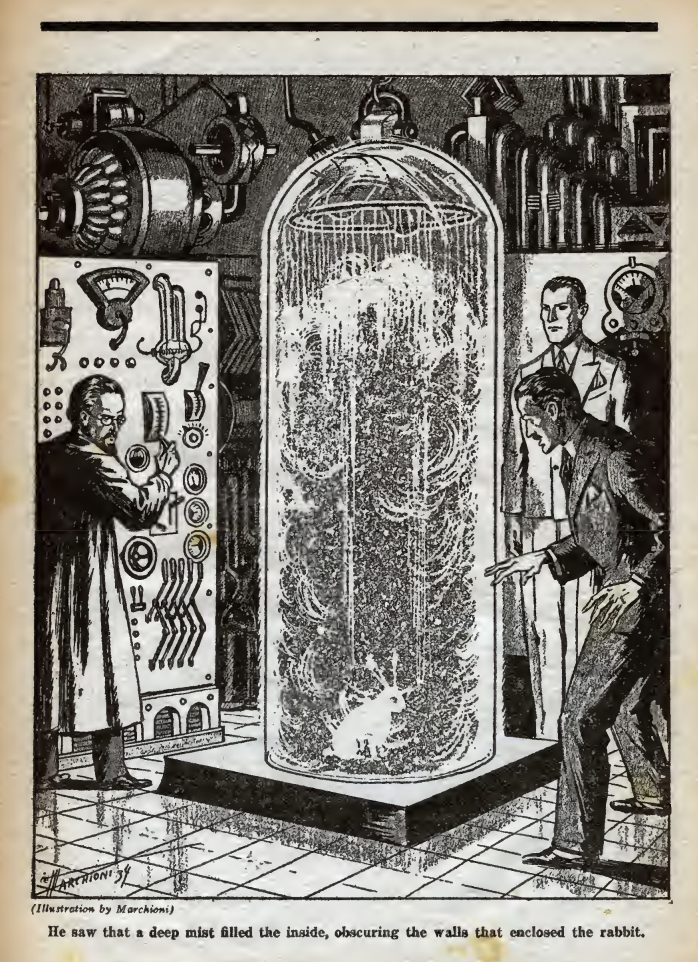

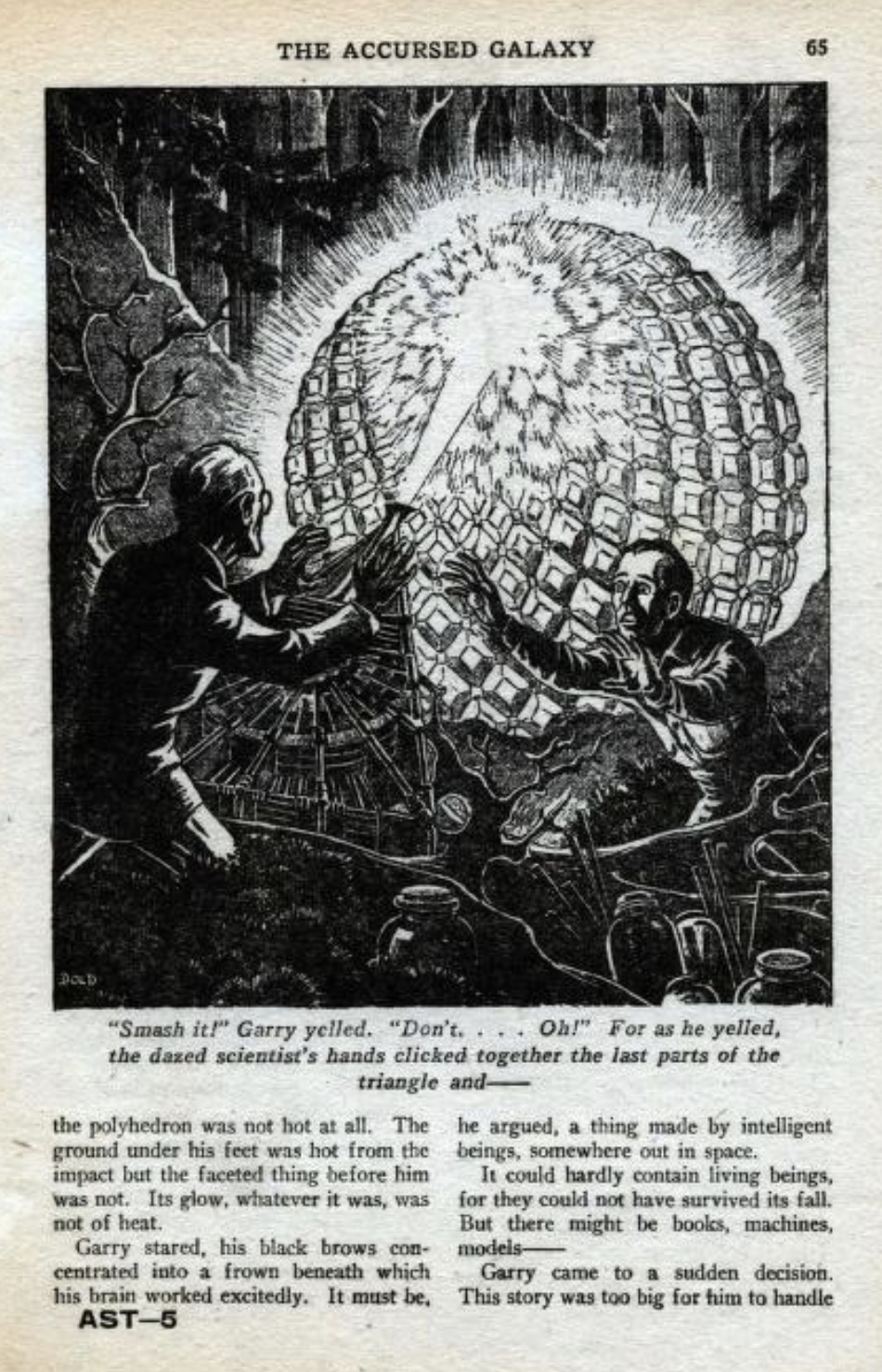

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Accursed Galaxy” (Astounding, July 1935). A story in which humankind is revealed to be castoff junk of other species. Adams, a NY newspaper reporter brings Peters, a scientist, to the site of a crashed UFO. The craft is a prison, holding an immaterial alien made of “force.” Through telepathy (which appears in every one of these stories), the alien tells the story of his crime, and of the creation of material life. At one time all life in the universe consisted of immortal force creatures. But then the prisoner, while experimenting with matter, accidentally brought some matter to life. This life spread throughout the universe like a disease, despite the best efforts of the force creatures to stamp it out. Eventually the force creatures resorted to quarantining infected solar systems in the center of the universe, and propelling galaxies of clean systems away – this explains the expansion of the universe observed by scientists via the phenomenon of red shift. It is our own galaxy which is accursed, and we ourselves are the curse. Fun facts: in her intro to The Best of Edmond Hamilton, Leigh Brackett uses this story as an example of a “streak of misanthropy” detectable in some of her husband’s work. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- Murray Leinster’s “The Fourth-Dimensional Demonstrator” (Astounding, December 1935) — humorous sf comparable to Weinbaum’s. Title of this amusing story refers to a gadget that “demonstrates the fourth dimension” — or rather, that it’s possible to travel along the fourth dimension, time, the way we can travel along the 3 spatial dimensions. But the application of time travel is ingenious.

- Naomi Mitchison’s We Have Been Warned. A tangled near-future political novel involving the oppression of the Left in the UK. Mitchison was Haldane’s sister.

- Neil Bell’s Mixed Pickles, his first and best adult story collection. Includes “The Mouse” and “The Evanescence of Adrian Fulk” and a sarcastic messianic fantasy, “The Facts About Benjamin Crede” (July 1932 The London Mercury). “The Mouse” about an inventive genius who brings happiness to the world but also makes it possible to destroy it; “The Evanescence of of Adrian Fulk” is a quirky macrocosmic fantasy; “The Facts About Benjamin Crede” is a fantasy about a man who can fly.

- Oswald Levett’s Papilio Mariposa. From Austria. Can be read as a fantastic allegory of the fate of the Jews: an ugly and strange individual is changed into a vampiric butterfly; feelings of inferiority and the desire for a fantastic harmony with an inimical environment result in tragedy. Oswald Franz Levett, actually David Loewitt (1884 – 1942) was an Austrian writer, lawyer and translator. In March 1939, Levett emigrated to Brussels , where he worked in the aid organization for Jews from Germany. In July 1940 he was arrested in Brussels; in 1942, he was deported to the Maly Trostinez extermination camp. Levett was not among the two survivors of this deportation.

- Ralph Milne Farley’s “The Man Who Met Himself.” Time travel story by prolific pulp sf writer.

- Raymond Z. Gallun’s “Davey Jones’ Ambassador.” Speculative biology akin to the best works of Weinbaum but more somber. Gallun was an unusually thoughtful pulp writer.

- Raymond Z. Gallun’s “Derelict” (Astounding Stories, October 1935). An early story about moral robots, by an unusually thoughtful pulp writer. When a long-abandoned alien ship is found orbiting Jupiter, an intrepid space explorer boards to discover what he can.

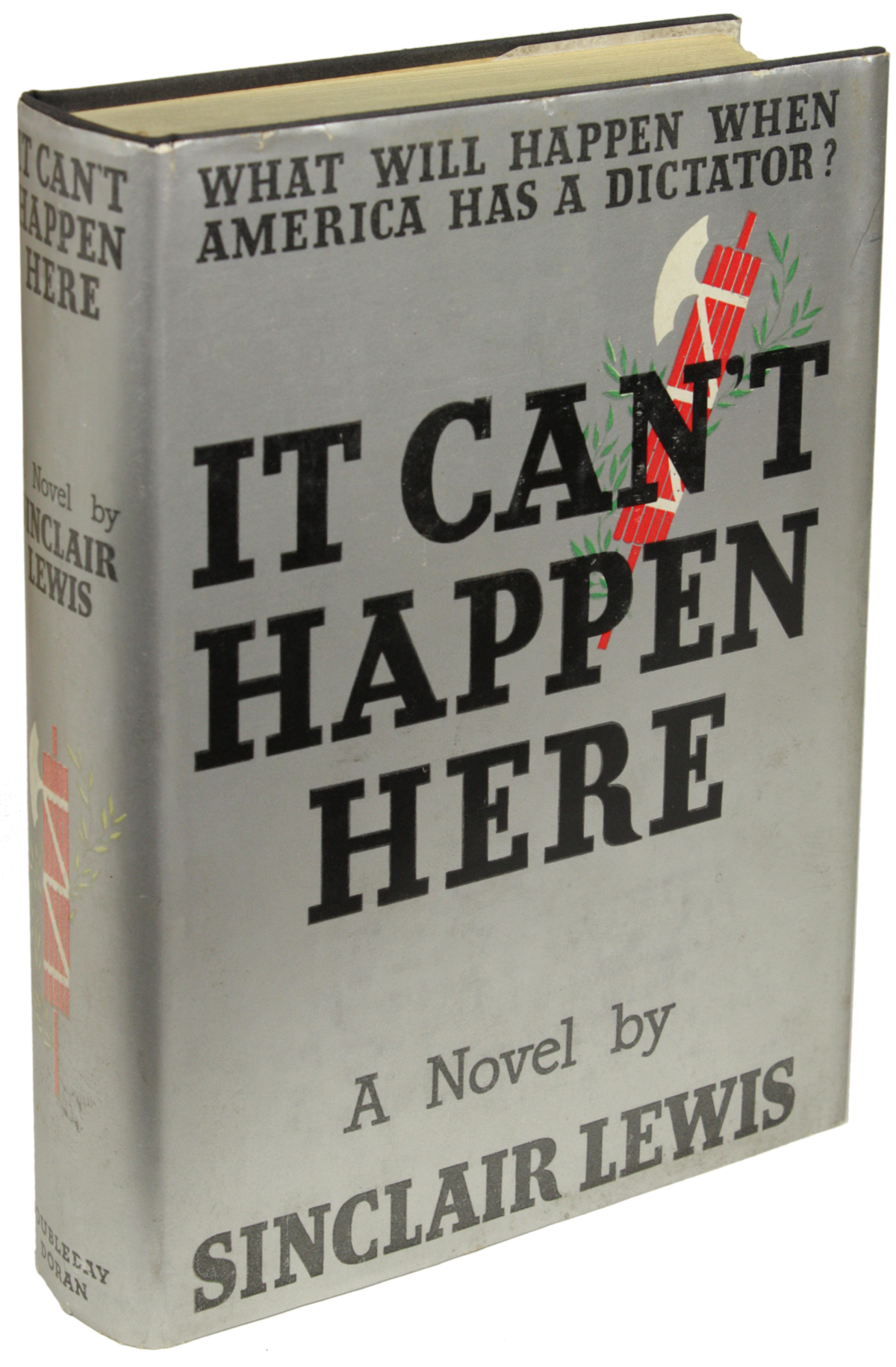

- Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here. The candidate of the “Forgotten Men,” the one who declared Americans “the greatest Race on the face of this old Earth,” and who runs on a platform against immigration, the liberal media, elites and welfare cheats, seems likely to clinch his party’s presidential nomination. Doremus Jessup, a small-town Vermont newspaper editor, sees something dark and terrible brewing in American politics — the potential for “a real fascist dictatorship” led by the up-and-coming populist candidate Berzelius Windrip. Friends scoff at this extravagant concern. “That couldn’t happen here in America, not possibly!” A work of dystopian fantasy, one man’s effort in the 1930s to imagine what it might look like if fascism came to America. At the time, the obvious specter was Hitler, whose rise to power in Germany provoked fears that men like the Louisiana senator Huey Long or the radio priest Charles Coughlin might accomplish a similar feat in the United States. Fun fact: After the 2016 US presidential election, this book was much discussed.

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “The Lotus Eaters.” Anatomy of Wonder says it’s among the best of all sf pulp stories. Super-intelligent plants. Collected in Moskowitz’s Masterpieces of Science Fiction; Moskowitz says Weinbaum is one of the truly important sf authors but one of the least known to the general public.

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “The Adaptive Ultimate” (November 1935 Astounding). Pamela Sargent’s introduction to More Women of Wonder credits Weinbaum with being more innovative than others in his treatment of female characters. She points out that this story has as its main character a female “superman.” A drab, plain woman named Kyra Zela is operated on — her pineal gland — and she becomes a chameleon-ike figure who adapts in order to survive and thrive in any circumstance. Published under a pseudonym and filmed in 1957 as She-Devil.

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “The Worlds of If.” Alternate History story, one of a series of comedies featuring the eccentric scientist Professor van Manderpootz. Considered among the best examples of sf pulp humor. The story’s title has often been used to describe sf itself

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “The Ideal” — another humorous Professor van Manderpootz story.

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “The Mad Moon.” Said to be one of his better stories. See Damon Knight’s Science Fiction of the Thirties; also Anatomy of Wonder. Appears in the 1980 anthology Science Fiction: The Best of Yesterday.

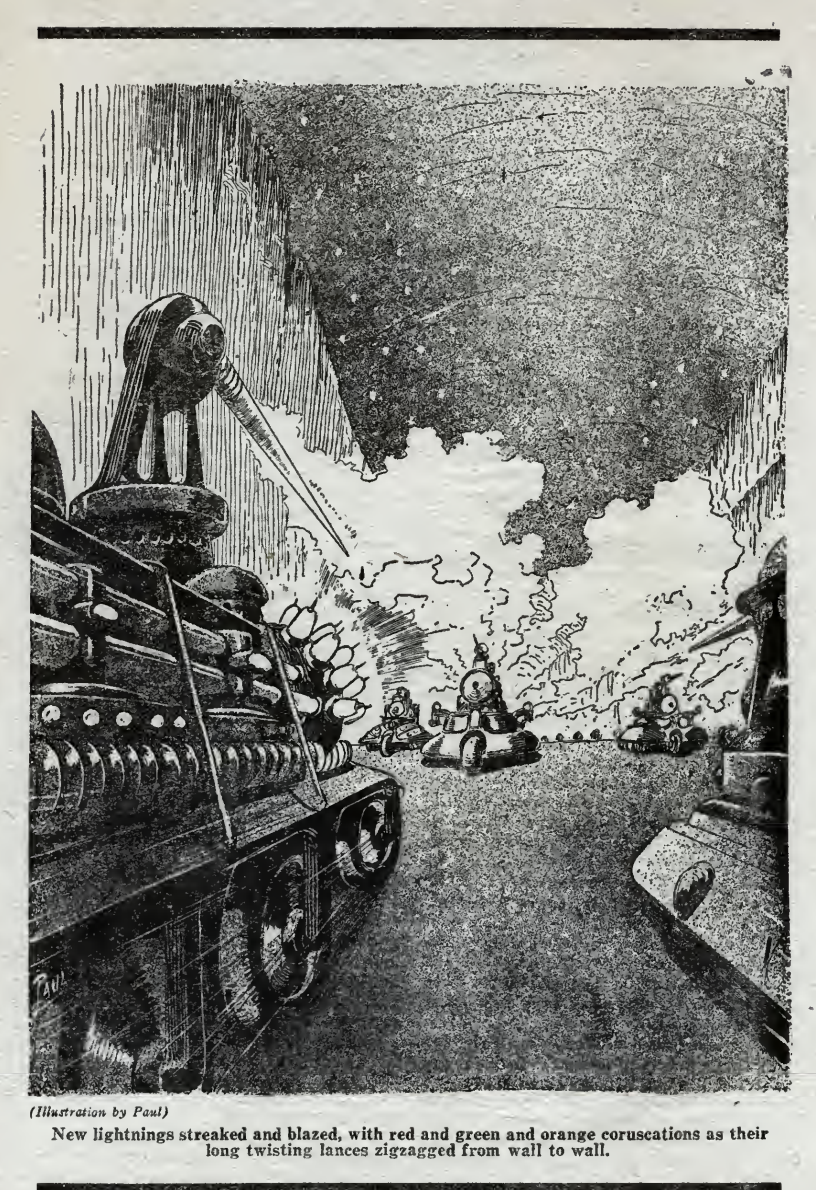

- Stanton A. Coblentz’s Hidden World (Mar, Apr, May 1935 Wonder). Considered the best of his heavy-handed satires. See Anatomy of Wonder. A cliff overlooking tremendous galleries and caverns and, far below, two armies battling with powerful destructive weapons…this was the place into which Comstock and Clay had been thrust by what they thought was an earthquake. Here, below the desert – below the silver mine which the two had been exploring – were two hidden civilizations, deadly enemies, and the possessors of far-advanced scientific secrets. Separated from his companion, Comstock finds himself captured by chalk-faced people and brought into a civilization that was both bewildering and awe-inspiring. For while the people of this Alice-in-Wonderland land of Wu appeared to be scientific geniuses, they look and act like madmen! Frank’s efforts to reform the society of Wu meet so much resistance and resentment that he is compelled to renew the war with Zu, whose own dictator has just been deposed. The new dictator of Zu turns out to be Clay in disguise.

- W.E. Johns’s Biggles Hits the Trail. Johns was the most popular British writer for children except for Enid Blyton. He became famous in particular for the 102 books about airman Biggles. This novel features a lost Himalayan mountain rich in radium, whose inimical inhabitants have harnessed this resource for invisibility and Death Rays.

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “The Red Peri” (Astounding). Pamela Sargent’s introduction to More Women of Wonder credits Weinbaum with being more innovative than others in his treatment of female characters. She points out that this story has as its main character a female space pirate.

- Benson Herbert’s Crisis! – 1992 (October 1935-January/February 1936 Wonder Stories; 1936 in book form as “The Perfect World”). With an introduction by M P Shiel. Deals with the ominous passage of another planet close to Earth’s orbit, and with what humans discover when they land on it: the planet is actually a World Ship.

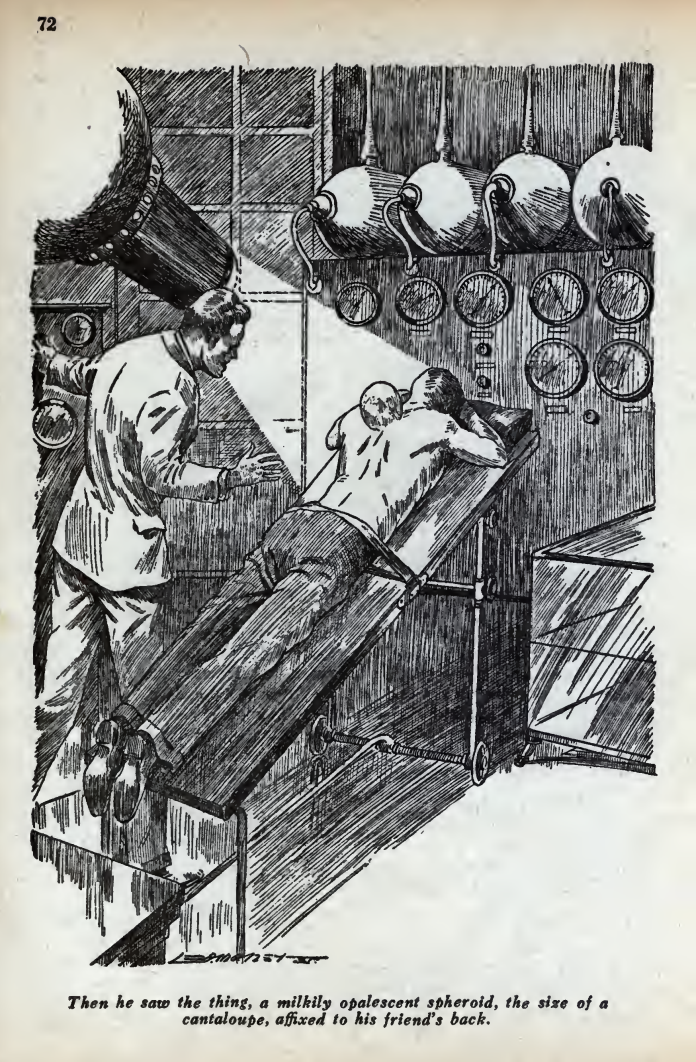

- Harl Vincent’s “Parasite” (Amazing Stories, July 1935). Invading aliens attach themselves to us and control our thoughts. This is fifteen years before Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters really popularized the “aliens among us” trope. PS: Edmond Hamilton had written about disguised aliens controlling humans’ lives in “The Earth-Owners” (1931). (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- Victoria Cross’s [aka Vivian Cory] Martha Brown, M.P.: A Girl of Tomorrow. Gender-role reversal satire. Set in a future in which women and men in England have exchanged traditional gender roles. The novel ends, however, with Martha Brown abandoning her English political career and going to America, where, apparently, men are still real men. Rich Horton writes: “Her attitudes on class — mainly represented by utter contempt for the ‘lower classes’ — were revolting. Her attitudes on gender were odd: on the one hand she thought women indisputably the superior sex: men, she wrote, had no interest at all in intellectual pursuit. On the other hand once a woman met her true lover she was bound to be submissive to him — a truly worthwhile man, if rare perhaps, was apparently far superior to any woman.” See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Susan Ertz’s Woman Alive, But Now Dead. A science fiction novel set after all women other than the titular heroine have perished in a plague. One hears that Mike Ashley is a fan. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Elise Kay Gresswell’s When Yvonne Was Dictator. An important work of feminist SF involving an 18-year-old Yvonne becoming prime minister of the UK and subsequently dictator. An optimistic, socialist novel with equality for women. “I trust that now we live in a war-free world, a world that accepts human woman as it accepts human man, that does not place the burden of taxation on shoulders that have not caused it, that does not make the State the foster-parent of its children – I trust that now we shall know an era the world never yet has known of joy, happiness, progress, and companionship.” See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Esther Meynell’s Time’s Door. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mairi O’Nair’s The Girl with the X-Ray Eyes. Features a young woman detective with the power of telepathy, which helps her solve her cases. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- David R. Daniels’s story “The Branches of Time.”

- Alan Connell;s novelette The Reign of the Reptiles

- Claire Myers Owens’s The Unpredictable Adventure: A Comedy of Woman’s Independence by Claire Myers Spotswood. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Alexander Laing’s The Motives of Nicholas Holtz (also published as The Glass Centipede). Persuasively authentic in its use of biological data, it is a well-told story of the creation of artificial life in the form of a deadly plague bacterium, threatening to create a pandemic, and of the dangers that beset the man who investigates the ensuing deaths. NB: Appeared on January 1, 1936 — so just barely outside the Radium Age era I’ve identified. Laing is best known for his books on the sea, and for editing influential anthology The Haunted Omnibus (1937). recommended to my attention by Frank Cioffi.

Also published as In Caverns Below. Ashley’s Time Machines says it’s a good satirical novel about an advanced subterranean society.

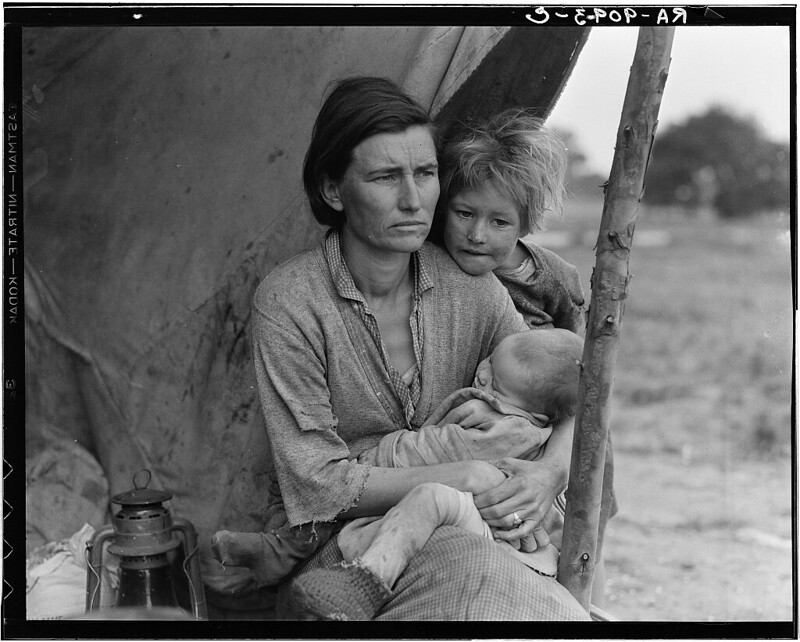

ALSO: Radar equipment to detect aircraft built. Nazis repudiate Versailles Treaty; Nuremberg Laws against Jews (Jewish citizens stripped of their citizenship); the Luftwaffe formed. (Germany in 1936 will occupy the Rhineland, and Hitler and Mussolini will declare the Rome/Berlin “Axis.”) Show trials take place in Russia — the beginning of a process by the end of which Stalin had arrested and executed almost every important living Bolshevik from the Revolution. Mussolini invades Abyssinia. Persia changes its name to Iran. The Dust Bowl strikes the middle of North America. CIO organized; Alcoholics Anonymous organized. Roosevelt signs US Social Security Act. Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat. Selznick’s David Copperfield, Mutiny on the Bounty, Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps. Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Conqueror (1935–1936); Hergé’s The Broken Ear; Dorothy L. Sayers’s Gaudy Night; C.S. Forester’s The African Queen.

Post-1935 sf that could arguably be included in the Radium Age canon includes:

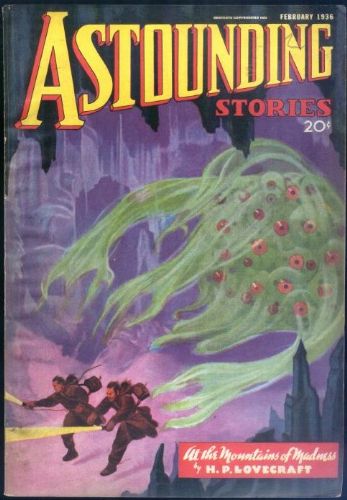

H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1936; as a book, 1964). A 1930 scientific expedition to Antarctica — from Arkham, Massachusetts’s Miskatonic University — discovers the ruins of a vast, ancient city… and the frozen bodies of some strange creatures, part-plant and part-animal. Part of the expedition is massacred — and it appears as though some of the frozen creatures have come back to life! Exploring the ruins, the surviving explorers determine that it was built by Elder Things, who first came to Earth shortly after the Moon took form, and built their cities with the help of shape-shifting, all-purpose “Shoggoths” (like Al Capp’s Shmoos, but uncannier). The Elder Things battled both the Star-spawn of Cthulhu and the Mi-go; and as the Shogvoths gained independence, their civilization began to decline. (Hello, Planet of the Apes.) Only one explorer escapes with his sanity intact… and he must warn another expedition to stay away from an even worse, unnamed thing which lurks in Antarctica! Fun fact: Originally serialized in the February, March, and April 1936 issues of Astounding Stories. Andrew Hultkrans analyzed At the Mountains of Madness for HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

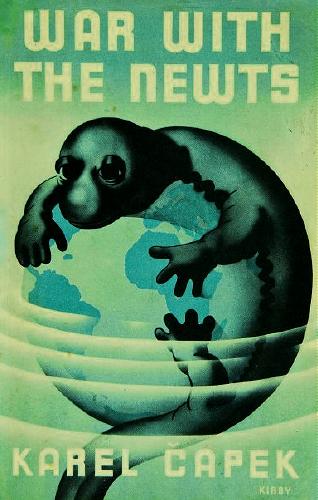

Karel Čapek’s Válka s mloky (War with the Newts, 1936). The light-hearted first section of the book, which skewers European attitudes towards non-white races, recounts the discovery of an intelligent but child-like breed of large newts, on a small island near Sumatra… and their enslavement and exploitation in the service of pearl farming and other underwater enterprises. The Newts develop speech, and absorb aspects of human culture. In the book’s second section, the Newts began to rebel against their masters — hello, Planet of the Apes. The final section of War with the Newts is darker in tone: It recounts the outbreak of war between the Newts and humans. The British, French and Germans are portrayed as stubborn and nationalistic; and we hear from a German scientist who has determined that the German Newts are actually a superior Nordic race, and who invokes lebensraum to justify their destruction of portions of the world’s continents. The final chapter is a metafictional exercise in which the Author and the Writer discuss what will happen next: The Newts will destroy the world’s landmasses and enslave humanity. Fun fact: Sci-fi scholar Darko Suvin has described War with the Newts as “the pioneer of all anti-fascist and anti-militarist SF.”

H.P. Lovecraft’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth (1936). While on an antiquarian tour of New England, this novella’s unsuspecting narrator visits Innsmouth, Massachusetts — a blighted seaport, near Arkham, which is populated entirely by people who look a bit odd and who tend to shamble. The narrator persuades an old-timer, named Zadok, to tell him about the town’s history… and hears a wild story about fish/frog-like humanoids known as Deep Ones, who helped Innsmouth’s fisherman prosper, in exchange for the occasional human sacrifice! It seems that an Innsmouth merchant, Obed Marsh, had discovered the creatures while on a voyage in the West Indies. (Which is why this is a science fiction horror story, not merely fantasy: it’s about a Lost Race.) Marsh established a church — the Esoteric Order of Dagon — in honor of the Deep Ones’ deity. Over time, the Deep Ones slaughtered some of Innsmouth’s residents, and bred with others; their offspring looked like normal humans, but only for a while. The narrator doesn’t believe Zadok’s story… and yet, Zadok disappears mysteriously. Later, the narrator discovers that he, himself, is descended from Obed Marsh — and that he may become a frog-man. Is he just going mad? Or will he dwell in the sunken city Y’ha-nthlei? Fun fact: This was the only one of Lovecraft’s full-length novels distributed during his lifetime. Lovecraft based the town of Innsmouth on his impressions of Newburyport, Massachusetts. Arkham, of course, is based on Salem. Anthony Miller analyzed The Shadow Over Innsmouth for HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937). Stapledon’s extraordinary, brilliant (if often difficult) novel describes a history of life in the universe, while exploring the philosophical notion that between different civilizations, no matter how physically and mentally dissimilar they may be, there must exist a progressive unity. Via unexplained means, our narrator is transported from England — and out of his body — into space. He explores alien civilizations on other worlds — and his consciousness merges with that of beings from these worlds, who then join him on his journey around the universe. Like humankind, we discover, alien species evolve in a Darwinian manner, and possess a capacity to value, to be aware, and to be creative. In addition to many imaginative descriptions of species, we encounter far-out technological marvels and sci-fi concepts: the first known instance of what is now called the Dyson sphere; descriptions of the Multiverse; the idea that the stars are intelligent beings; the formation of a networked consciousness spanning planets, galaxies, and even the cosmos; and a Star Maker who creates the universe but views it without any feeling for the suffering of its inhabitants. At last, invested with cosmic consciousness, our narrator returns to Earth at the place and time he left. Fun fact: Stapledon’s novel has been praised by H. G. Wells, Virginia Woolf, Brian Aldiss, Doris Lessing, Stanisław Lem, Jorge Luis Borges, and Arthur C. Clarke.

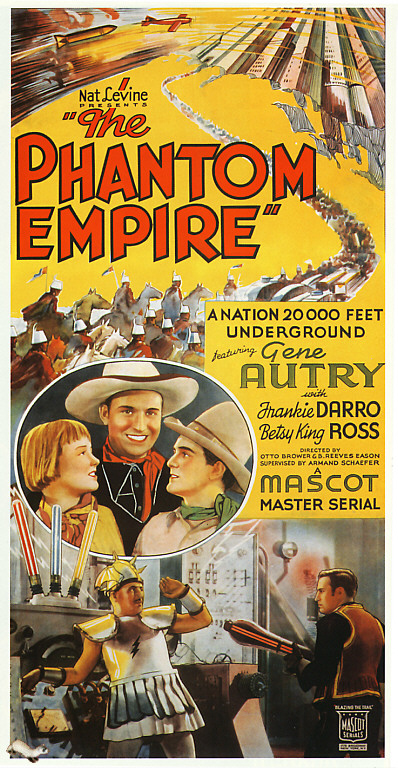

The Golden Age of film serials — low-budget, quickly-produced shorts depicting futuristic, heroic adventures, action, melodramatic plots, and gadgetry — begins with The Phantom Empire (1935) starring Gene Autry, about an advanced underground civilization which had ray guns and television communication screens. The serials will really take off the following year with Ace Drummond (Universal), Flash Gordon (Universal), The Adventures of Frank Merriwell (Universal), Undersea Kingdom (Republic), etc. Buck Rogers in 1939. The quasi-science fiction Dick Tracy serials begin in 1937. Sf serials featured elements like space travel, high-tech gadgets, plots for world domination, and mad scientists — all still popular today.

In a 1935 paper, Einstein and Nathan Rosen showed that general relativity predicted that black holes (which were not yet known by that name) could form in pairs connected by shortcuts through space-time, called Einstein-Rosen bridges — what sf writers (following physicists) would call “wormholes.” But in another 1935 paper, Einstein, Rosen and Boris Podolsky pointed out a seeming logical inconsistency in quantum mechanics. They pointed out that, according to the uncertainty principle of quantum physics, a pair of particles once associated would be eternally connected, even if they were light-years apart. Measuring a property of one particle — its direction of spin, say — would instantaneously affect the measurement of its mate. If these photons were flipped coins and one came up heads, the other invariably would be found out to be tails. To Einstein this proposition was ludicrous, and he dismissed it as “spooky action at a distance.” But today physicists call it “entanglement,” and lab experiments have confirmed its reality.

Physicist Daniel Kabat told the New York Times (in October 2022): “We’re used to thinking that information about an object — say, that a glass is half-full — is somehow contained within the object. Entanglement means this isn’t correct. Entangled objects don’t have an independent existence with definite properties of their own. Instead they only exist in relation to other objects.”

Einstein probably never dreamed that the two 1935 papers had anything in common. But physicists now speculate that wormholes and spooky action are two aspects of the same “magic.” In 2012 Drs. Maldacena and Susskind They proposed that spooky entanglement and wormholes were two faces of the same phenomenon. As they put it, employing the initials of the authors of those two 1935 papers, Einstein and Rosen in one and Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen in the other: “ER = EPR.”

Haldane’s Philosophy of a Biologist.

Julian Huxley’s We Europeans: A Survey of ‘Racial Problems’ (with anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon) debunks what its authors called a “vast pseudo-science of ‘racial biology'” endorsed by fascist nationalists. He fought against Nazism and race science for years. At the same time, he was racially prejudiced and a major proponent of eugenics.

J. B. S. Haldane and Julian Huxley were undoubtedly the best-known British biologists during the first half of the century. Their fame rested only in part upon their scientific achievements. Otherwise, they were recognized and respected for their popularizations of science, the breadth of their intellects, and, not unimportantly, the luster of their family names. They combined progressive and sometimes socialistic agendas with eugenic fervor. For them, genetic planning was a facet of the modern utopian state: a tool for good that needed to be severed from the corrosive evils of ethnonationalism and racial prejudice. See their 1939 geneticists’ manifesto.

Bernard Wolfe (1915-1985) earned a BA in psychology from Yale in 1935, worked for two years in the Merchant Marine, and for a time was personal secretary to Leon Trotsky in Mexico. He began publishing work of genre interest with the novelette “Self Portrait” in Galaxy for November 1951, soon following this with his only sf novel, Limbo (1952). From 1935–1938, Theodore Sturgeon (aged 17) was a sailor in the merchant marine, and elements of that experience would find their way into several of his stories.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin