RADIUM AGE: 1931

By:

November 21, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

Astounding Stories of Super Science shortened its title to Astounding Stories in 1931 the same year also saw Amazing change hands again; this time it was acquired by Macfadden.

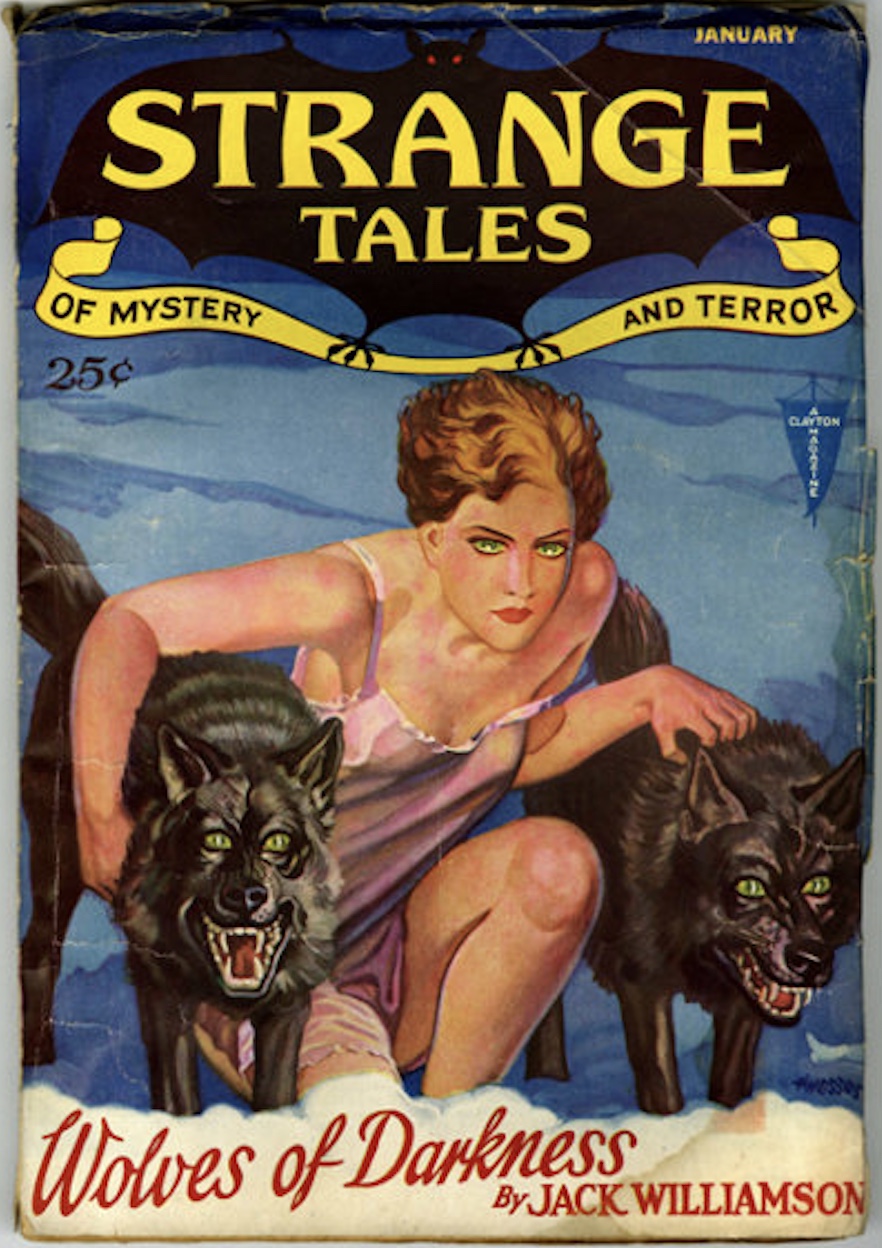

In 1931 Weird Tales got some direct competition from Strange Tales, which frequently published sf as well as fantasy. Like Astounding it paid better rates than the competition, and as a result attracted some good writers, including Jack Williamson, whose “Wolves of Darkness” is one of its better-remembered stories. Strange Tales would fold in 1933. Miracle Science and Fantasy also appeared in 1931 — by all accounts an inferior pulp mag. The other offshoot of the detective pulps (besides weird menace) was the hero pulp. Street & Smith led the way again with The Shadow (Apr. 1931-Summer 1949), a spin-off of a radio series.

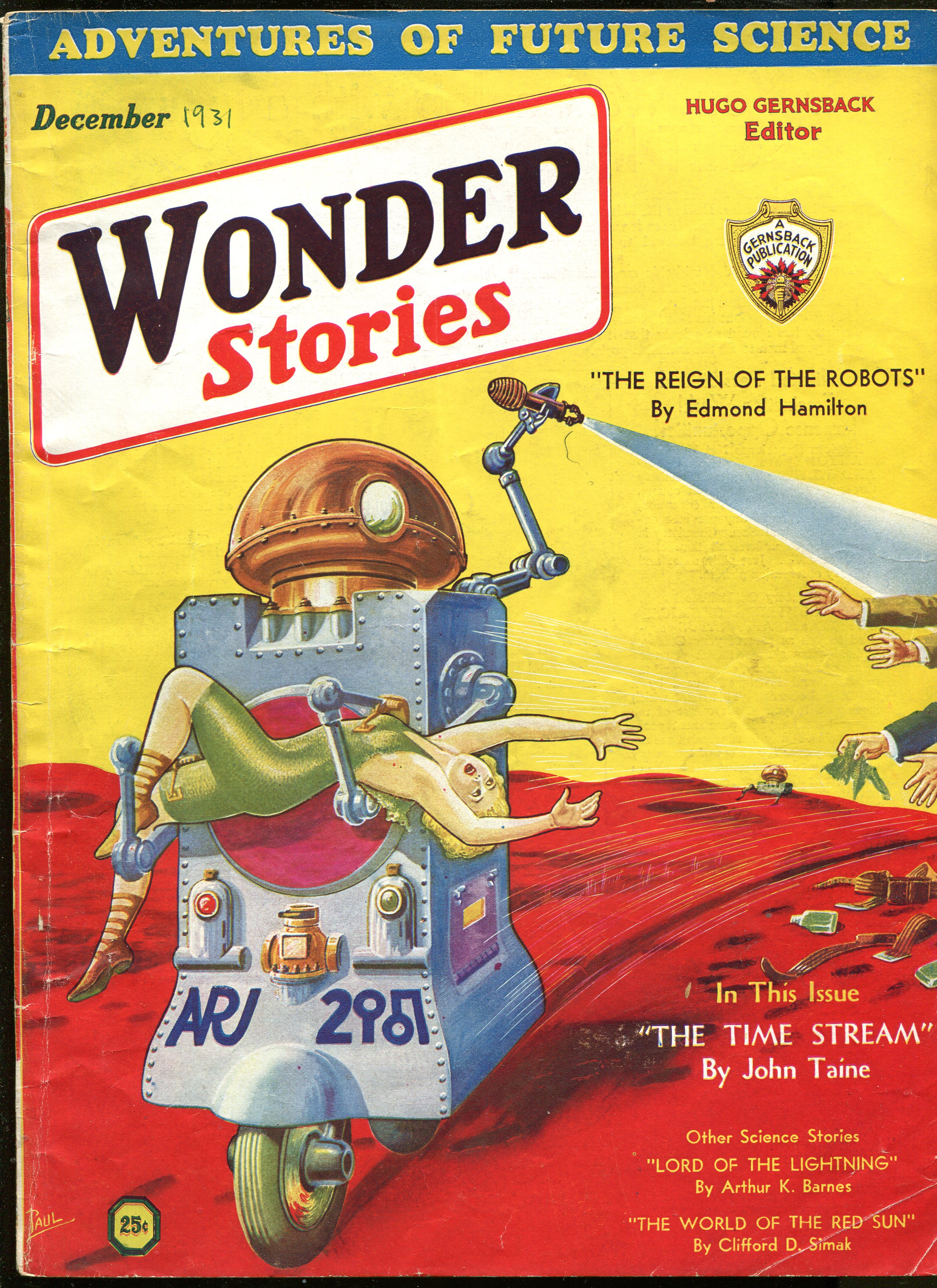

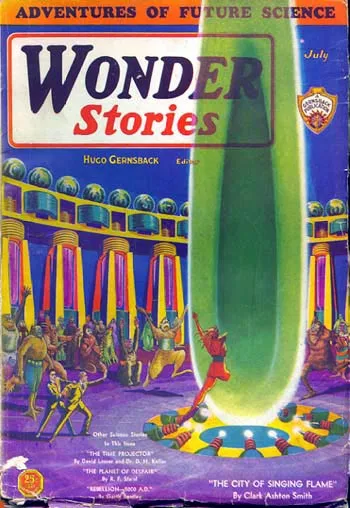

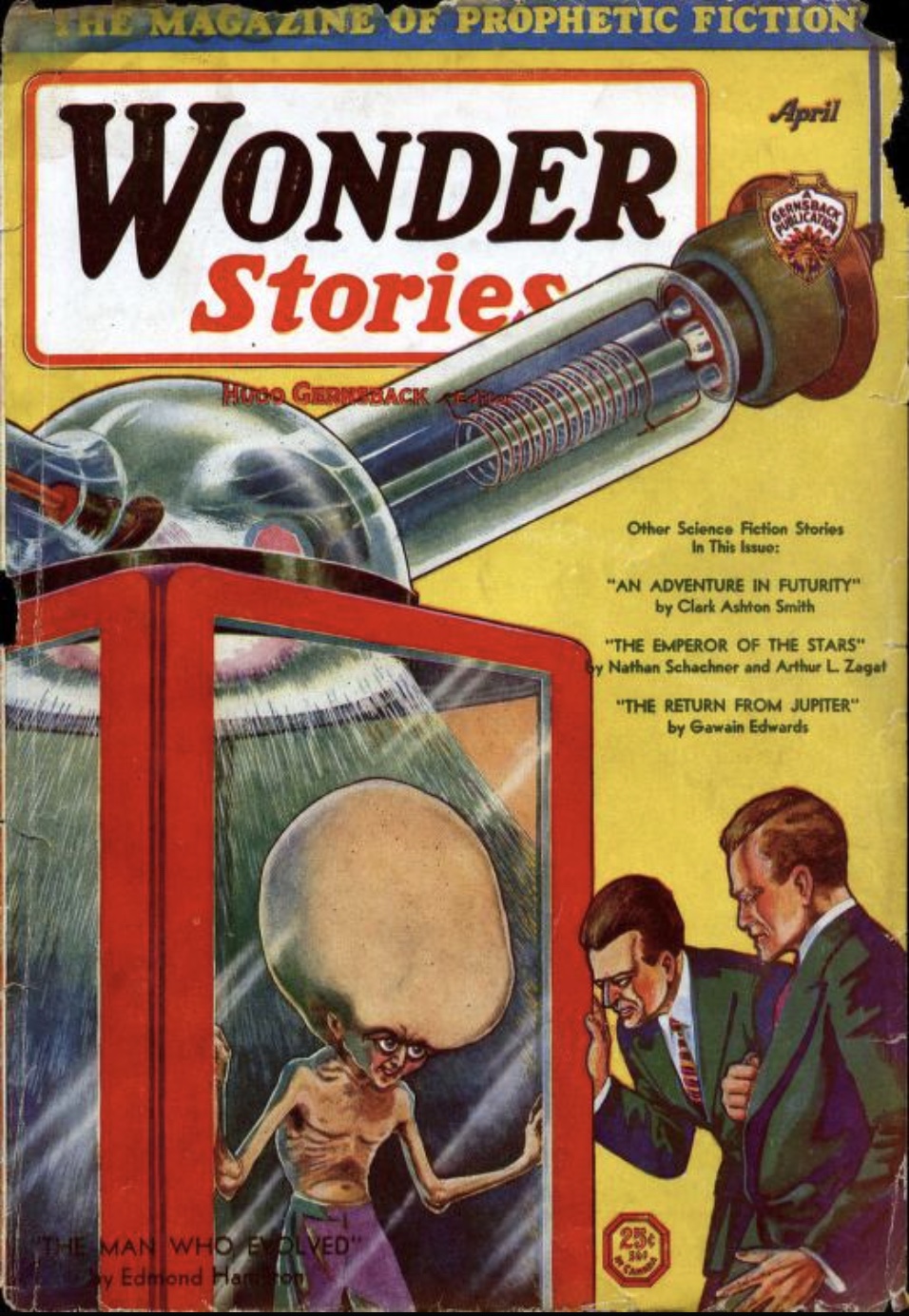

At Wonder Stories, David Lasser remained as editor during the early 1930s. He corresponded with his authors to help improve both their level of scientific literacy, and the quality of their writing; Asimov has described Wonder Stories as a “forcing ground” where young writers learned their trade. Lasser was willing to print material that lay outside the usual pulp conventions, such as Eric Temple Bell’s The Time Stream and Festus Pragnell’s The Green Man of Graypec. John Clute gives Lasser credit for making Wonder the best sf magazine of his day, while Peter Nicholls and Brian Stableford agree that Wonder was the best of Gernsback’s forays into the sf genre. A May 1931 letter from David Lasser to Wonder regular writers (quoted in Ashley’s Time Machines) outlaws space opera, giant insects, hero-vs-monster stories, and asks instead for realistic themes around sex, feminism, and religion, etc. Despite his success, though. Lasser would be let go by Gernsback in mid-1933.

Copyrighted works from 1931 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2027. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1931, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ASTROGATION | DEFLECTOR | DIMENSIONAL | DISRUPTOR | FORCE FIELD | FREE FALL | FUTURE WAR | GATE (a matter transmission device, esp. a portal or device by means of which something may be (instantaneously) transported to another point in space or time, or into another dimension or alternate universe) | MATTER TRANSMITTER | NORMAL SPACE (in contrast to hyperspace) | PARALLEL WORLD | SCIENCE FANTASY | SPACE HELMET | TELEPORT | TIMESTREAM | TRACTOR BEAM | TRANSDIMENSIONAL.

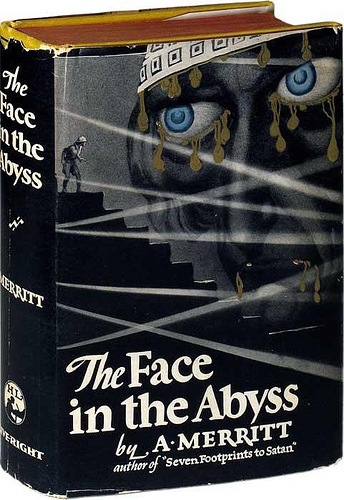

- A. Merritt’s The Face in the Abyss (1931). This semi-occult SF novel, which combines “The Face in the Abyss” (serialized Sept. 1923) and its sequel, “The Snake Mother” (serialized Oct.-Dec. 1930), is set in the Peruvian Andes. Treasure-hunter Nicholas Graydon rescues Suarra, handmaiden to Adana, the Snake Mother of Yu-Atlanchi, from his own companions. Adana is the last of a race of superintelligent serpent people whose servants, the Old Race, are immortal. Although possessed of fragments of their former superior science, they are now obsessed with sex, hunting mutants with dinosaurs, and dream machines. Adana, who possesses spectacular paranormal abilities, is humankind’s only defense against Nimir, a Sauron- or Voldemort-like mage who’d conquer the world if he could inhabit a physical body. He wants Graydon’s, but his designs are thwarted by a band of Old Race outlaws and mutated spiders. Fun fact: Merritt was once considered the greatest SF writer of modern times; he had a magazine — A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine — named after him. E.F. Bleiler praises his “sweeping ideas, high emotion, and perpetual suggestions of deeper phenomena beneath the surface of events.”

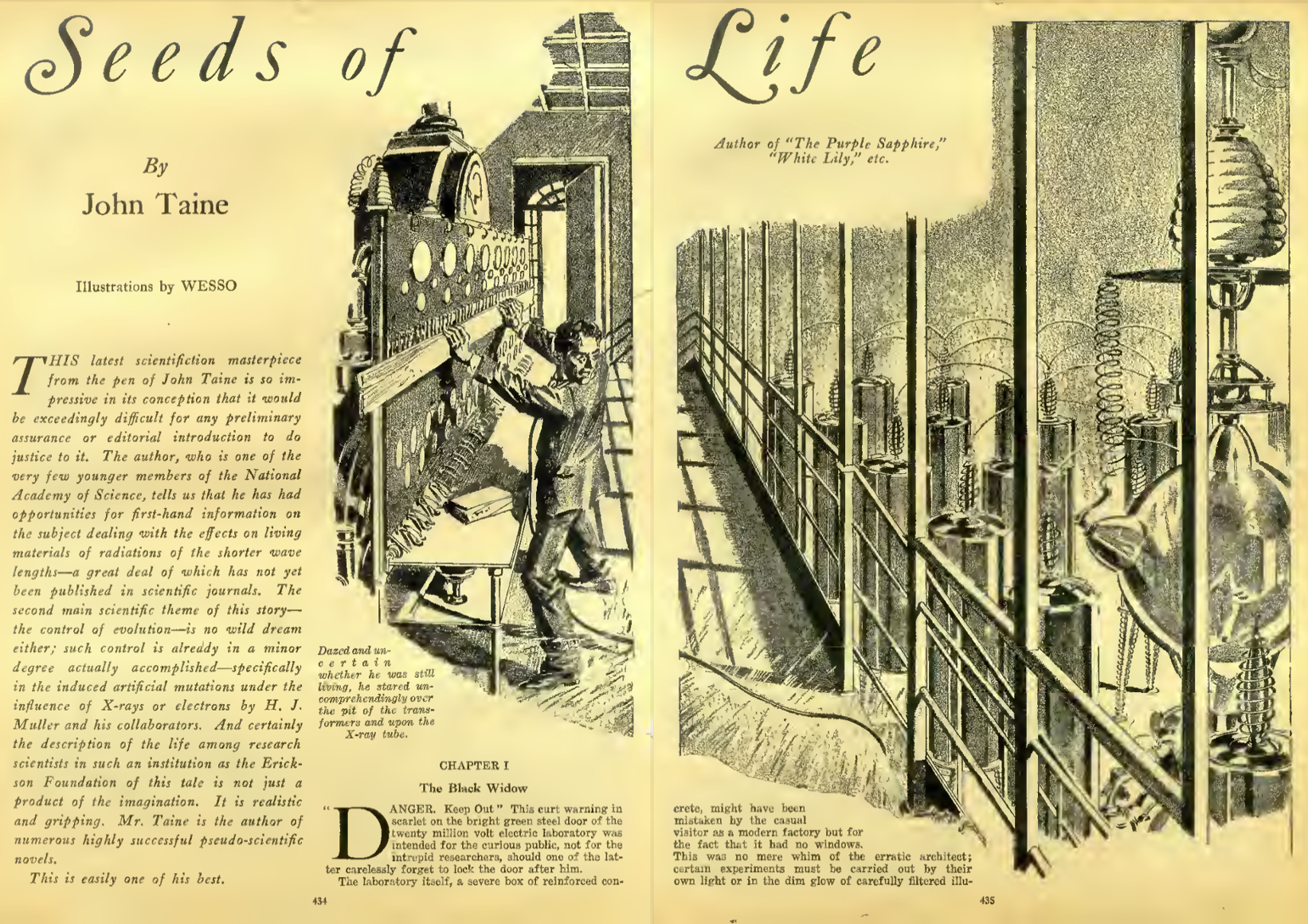

- John Taine’s Seeds of Life (1931). Neils Bork, a pathetic lab technician, attempts suicide via X-rays and is transformed into a supermind in the body of a swarthy Adonis; he renames himself De Soto. (“De Soto was but a partial, accidental anticipation of the more sophisticated and yet more natural race into which time and the secular flux of chance are slowly transforming our kind.”) He invents wireless energy transfer devices, secretly planning to use them to bombard humankind with “dysgenic” rays that will devolve unborn children. Then De Soto’s own evolution reverses itself: “I never used to think [i.e., while he was still a super-genius], but saw the inevitable consequences of any pattern of circumstances — no matter how complicated — immediately, like a photograph of the future.” He repents of his superioristic ways, and is killed by his own reptilian offspring. Fun fact: John Taine was the pseudonym of noted mathematician Eric Temple Bell. The novella, which may have influenced everything from Flowers for Algernon to Spider-Man, was serialized in Amazing Stories Quarterly. Bleiler found the opening segment of the novel to be “fascinating,” but that as a whole “it suffers from formal defects, inadequate development at times, superfluity at others, weak characterizations, and problems with tone.” Still, he concluded, “the novel is well worth reading for its virtues.”

- Neil R. Jones’s Professor Jameson stories (1931-68). In 1958, Professor Jameson arranges for his body to be cryopreserved — in a rocket orbiting the Earth — after he’s dead. Forty million years later, a crew hailing from the planet Zor, whose inhabitants had “built their own mechanical bodies, and by operation upon one another had removed their brains to the metal heads from which they directed the functions and movements of their inorganic anatomies,” discover the satellite. The Zoromes transfer Jameson’s brain into a machine body, then take him to visit the lifeless Earth, an experience that nearly drives him mad, until he realizes that “He could be immortal if he wished! It would be an immortality of never-ending adventures in the vast, endless Universe among the galaxy of stars and planets.” Indeed, Jones would publish 21 more Professor Jameson stories. Are they well-written? Not particularly. However, Jones’s stories were popular at the time, and their cyborg conceit is a terrific one. Asimov claimed the Zoromes, who although technically cyborgs are robot-like in their thorough-going objectivity, gave him his “feeling for benevolent robots who could serve man with decency.” Jones is also credited with inspiring the modern idea of cryonics. Fun fact: The first story in the series is “The Jameson Satellite” (Amazing Stories, July 1931), which is included in Voices from the Radium Age (MIT Press), a 2022 story collection edited by yours truly.

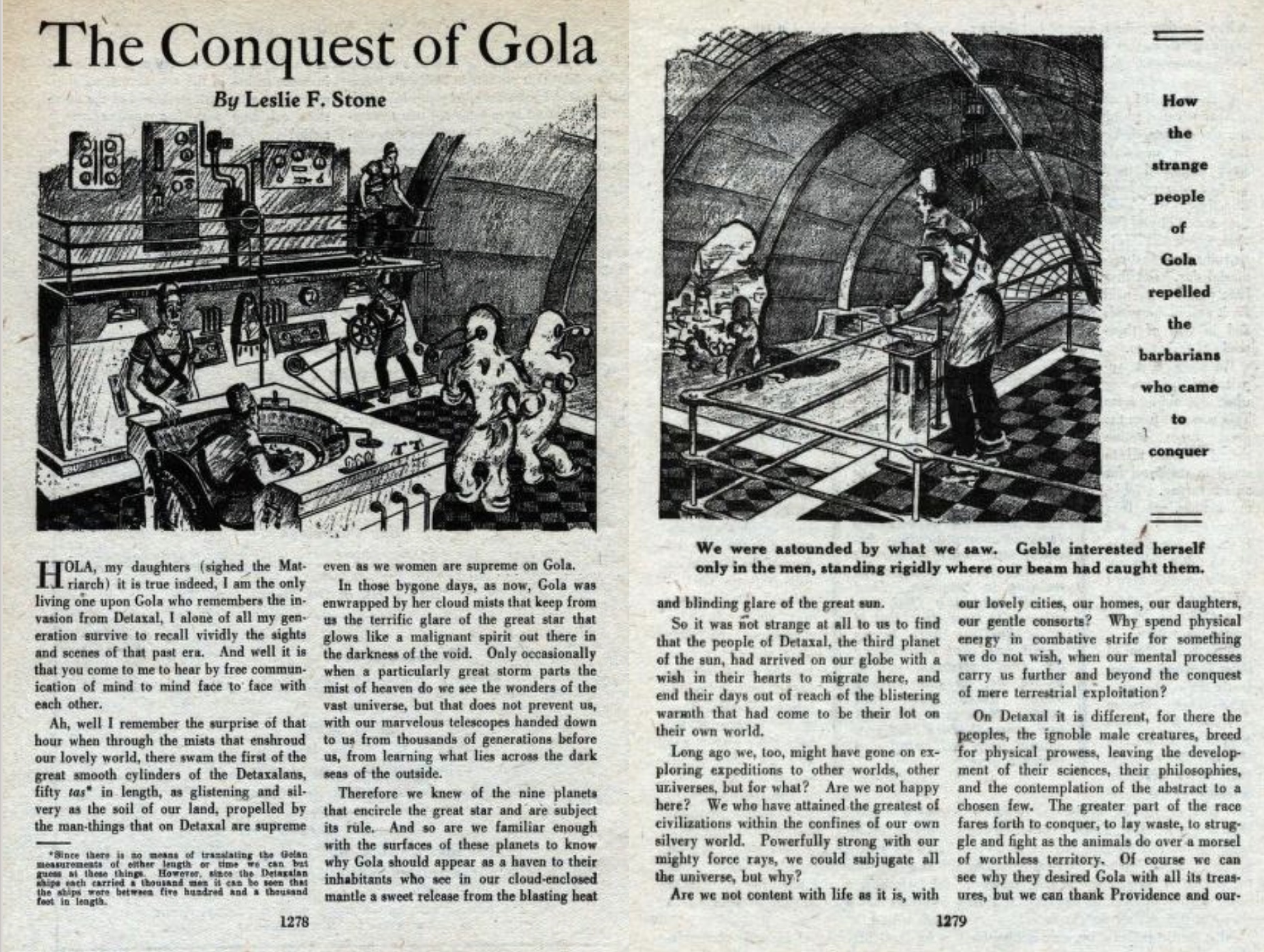

- Leslie F. Stone’s “The Conquest of Gola” (1931). When men from Earth invade Gola (Venus), the planet’s superioristic, Amazonian females — who keep their own passive males as mere houseboys and playthings — fight them off with contemptuous ease, deploying advanced military tech (including laser weapons) and psychological tactics. Narrated by a Golan, the story takes men — and humans, generally speaking — down a peg or two, by viewing them (us) from the perspective of a higher life-form, a non-humanoid alien with attitude. Why are human bodies so inefficient — their organs restricted by function and location? Why do the females of Earth send their hapless males to explore, negotiate, and invade? Fun facts: Stone was one of a very few female authors in sci-fi publisher Hugo Gernsback’s inner circle. The story was serialized in the April 1931 issue of Wonder Stories; reprinted in Groff Conklin’s The Best of Science Fiction in 1946. Also collected in Lisa Yaszek’s excellent 2018 collection The Future Is Female! 25 Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women.

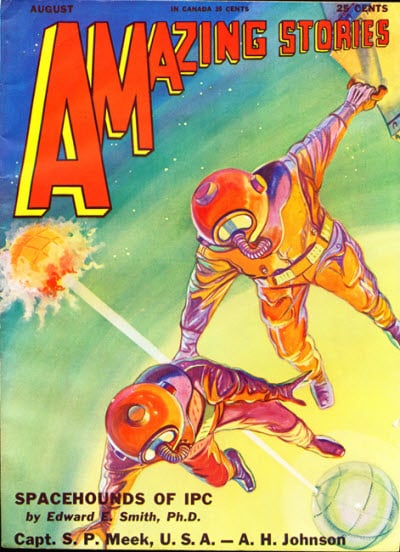

- E.E. “Doc” Smith‘s Spacehounds of IPC (serialized 1931; as a book, 1947). This stand-alone novel — unconnected to the author’s more famous Skylark and Lensman series — is a Robinsonade set mostly on Ganymede, one of Jupiter’s moons. Dr. Percival Stevens, a brilliant scientist, is traveling to Mars aboard the Inter-Planetary Corporation’s liner IPV Arcturus, when it is attacked — by pirates? — and cut into pieces. Commandeering one of the liner sections, Stevens and Nadia, a beautiful passenger, crash-land on Ganymede and begin building an ultra-radio — in order to call for help. Fleeing Ganymede’s native inhabitants, the castaways head back into space, only to be attacked again. They are rescued by explorers from Titan, one of Saturn’s moons. And a lot of other stuff happens — it’s a space opera, after all. Fun facts: Published in the August through September 1931 issues of Amazing; the first story to ever use the sci-fi term “tractor beam.” This was Smith’s own favorite novel, which he described as “really scientific fiction; not, like the Skylarks, pseudo-science.” Moskowitz in Seekers of Tomorrow says it’s as good as Skylark Three — though readers were disappointed he didn’t leave the Milky Way for this one

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Fighting Man of Mars (see 1930) published in book form.

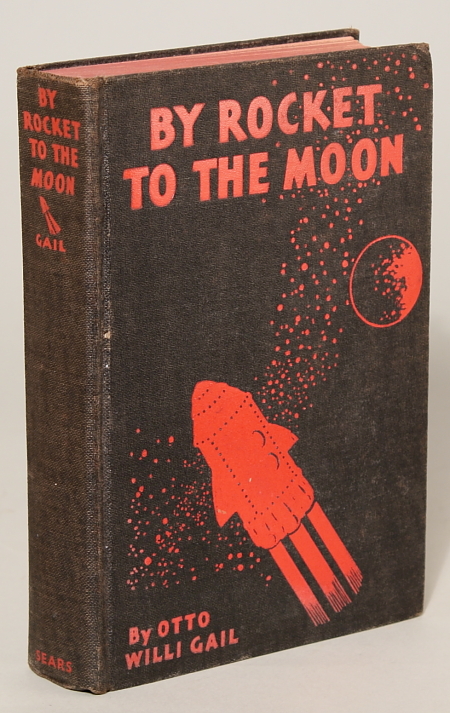

- Otto Willi Gail’s By Rocket to the Moon. (Hans Hardts Mondfahrt, 1928.) First edition in English. Boys’ book, fairly realistic in its description of the first flight into space. “Despite Atlantis and life on the moon, the author has very carefully used the best scientific and technological data of his day, and much of what he says seems very modern.” – Bleiler.

- John Collier’s “Green Thoughts” — appears in the 1943 anthology The Pocket Book of Science Fiction, edited by Donald A. Wollheim.

- P. Schuyler Miller’s “The Man from Mars.” Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

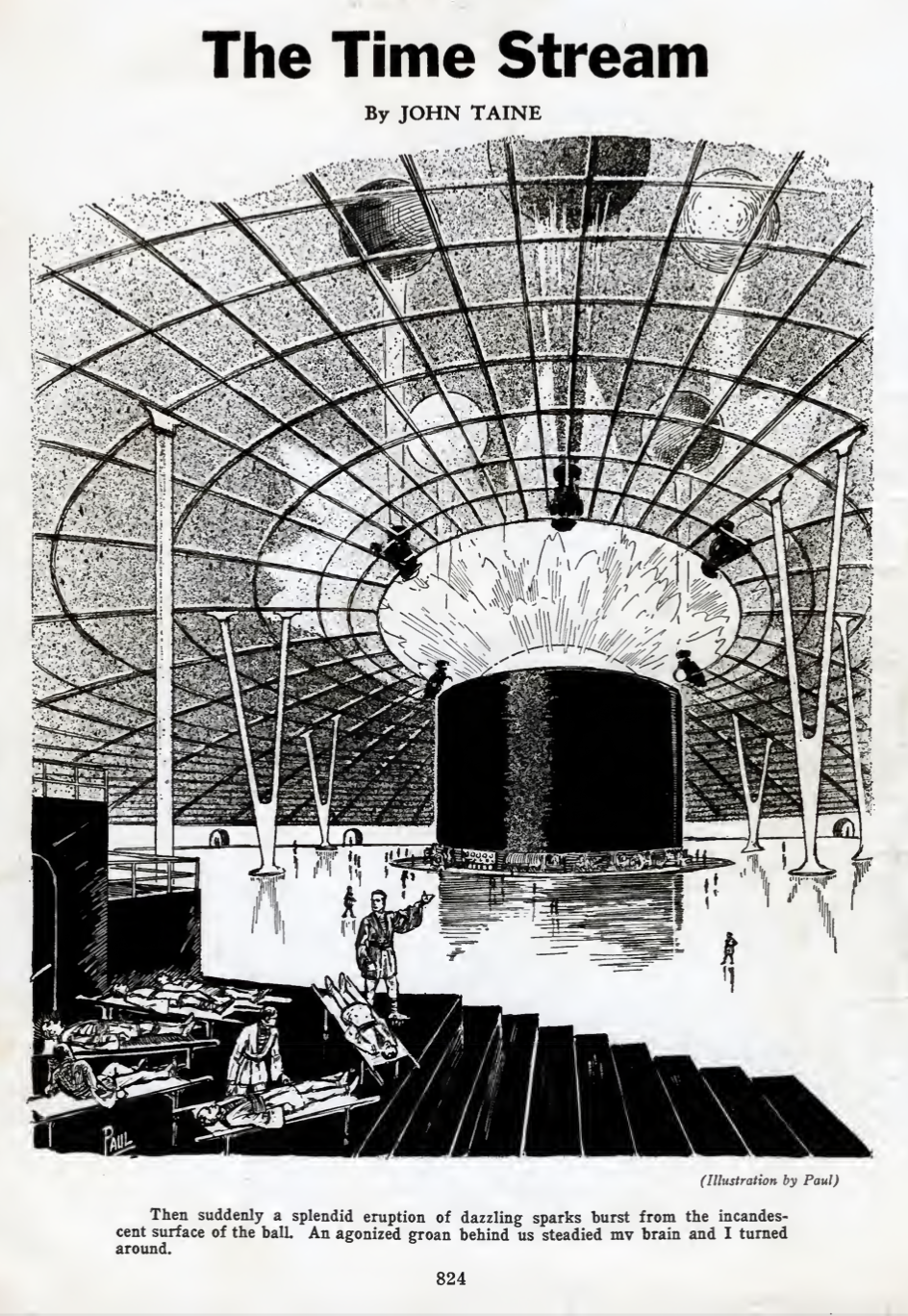

- John Taine’s The Time Stream (serialized 1931–1932, Wonder Stories). Although genetic analysis indicates that Cheryl, citizen of a far-future utopia (on a world, Eos, which might or might not be Earth), ought not to marry the man she loves — because their children will not be perfect specimens — she demands the right to do whatever she pleases. After all, what harm could following your passion do? One of her friends, having discovered that an even mightier civilization once flourished on their planet, speculates that it was uncontrolled passion which doomed it. Cheryl and four friends set out to discover the truth. Meanwhile, on our earth, in the 20th century, a woman named Cheryl and four friends enter the “time stream” — time, they have discovered, is like flowing water; it has eddy currents that can be used to move both forward and back — and discover Eos. Or something like that. It’s a very complicated narrative! Fun fact: Serialized in Wonder Stories, this elaborate time-travel yarn has been called “one of the outstanding products of the early sf magazines,” and Taine’s finest — if flawed — work. His best according to Anatomy of Wonder. Bleiler notes that it is “generally conceded to be Taine’s best novel, despite its somewhat confusing presentation and very ambivalent theme”; he concluded that the ambivalence “makes the novel interesting.”

- John Collier’s No Traveller Returns (1931). When a Professor Wilkinson descends into a London subway station from whence he has never observed anyone to exit, he finds himself in a dystopian future. He and other victims from the same era are stripped and held in cages, before being eaten; only his scrawniness spares him. Eventually, his mathematical doodlings are noticed, and Wilkinson is purchased as a music-hall act. (Foreshadowing Pierre Boulle’s 1963 adventure Planet of the Apes.) In this future England, it transpires, the vast majority of people have settled into a bovine complacency; a few “atavistics,” however, seek sensation and vividness of life. Wilkinson escapes, disguises himself as an atavistic, and finds shelter with an “uninventor” — i.e., a voluntary simplicist who finds ways to do without the things science has created. Eventually, attempting to return to his own time, Wilkinson ends up being captured… and eaten. Fun fact: This novella was published in a limited edition of 210 copies, very rare now. The author never permitted the story to be reprinted.

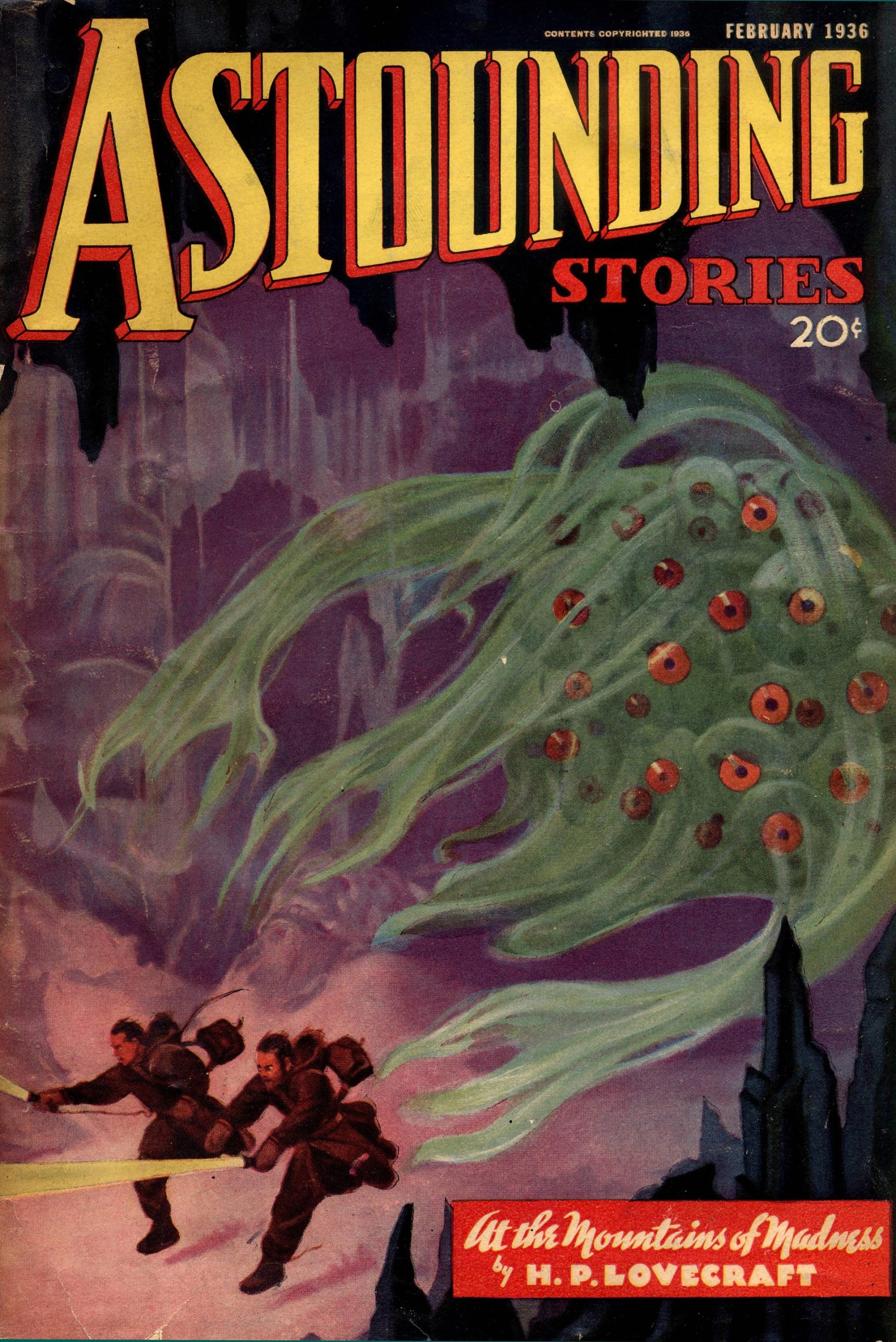

- Lovecraft writes his novel At the Mountains of Madness February 22-March, 1931 — not published until 1936. Based very closely on Byrd’s 1928 first expedition to the Antarctic. Also see John Taine’s The Greatest Adventure.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “An Adventure in Futurity” (Wonder Stories, April 1931).

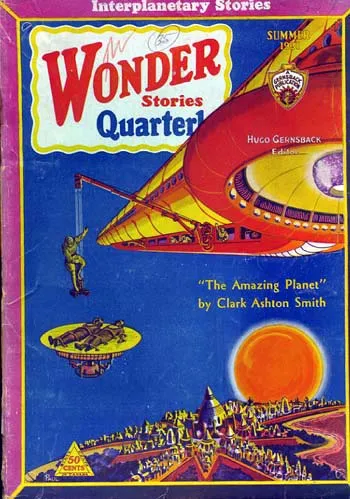

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Amazing Planet” (Wonder Stories Quarterly, Summer 1931).

- A. Rowley Hilliard’s “The Green Torture.” Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

- P. Schuyler Miller and Walter Dennis’s “The Red Spot of Jupiter” (Wonder Stories). Now that space opera was outlawed in Wonder Stories, this story brings grim realism to the exploration of space and relies on character development. Followed by “The Duel on the Asteroid”

- Don Mark Lemon’s “The Scarlet Planet” (in Wonder Stories Quarterly)> Caused an outcry among readers. Sexual adventures of spacemen on a female-occupied planet — a spoof on male dominated society.

- Anthony Gilmore (Harry Bates and Desmond Hall)’s “Hawk Carse.” First in the Hawk Carse series — worth mentioning here because Ashley’s Time Machines calls it a nadir for pulp sf!

- André Maurois (Émile Salomon Wilhelm Herzog)’s The Weigher of Souls. A doctor discovers that the élan vital is a gas which escapes the body at death; his attempts to mingle in posthumous harmony with his wife are, however, frustrated. The Weigher of Souls & The Earth Dwellers (1963) combines this tale with an episode in the Fragments of Universal History — loosely connected satires. Supposed to be an excellent novella in which experimental science meets theological supposition.

- Berilo Neves’s A mulher e o diabo. Story collection.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s The City of Singing Flame. One of his few stories that seem comfortable with the demands of genre sf (July 1931 Wonder Stories). Notable for the power of the sense of wonder it evoked. A Merrittesque tale about another dimensional world.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Heads of Apex” (Astounding, October 1931) has two soldiers of fortune being hired by a strange looking cripple named Solino. He takes them in a submarine to fight in a war undersea. The sub crashes, killing Solino and revealing his wheelchair to be a robot cart and the dead man only a head. They leave the sub for a creepy cavern. There they find a shining pyramid that sends them to another dimension. Arriving in this other phase of our dimension they are attacked by tall, green warriors. They are rescued by more head-men riding on wheeled devices. The Head Men of Apex are the survivors of Atlantis, from 300, 000 years ago, and are scientists who have given up their bodies for eternal machine life.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Planet Entity” (Wonder Stories Quarterly, Fall 1931).

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Beyond the Singing Flame” (Wonder Stories, November 1931).

- Benson Herbert’s “The World Without” (Parling & Klington). Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

- Clifford D. Simak’s “The World of the Red Sun” (Wonder Stories December 1931). The author’s first sf story. Deals with time travel, which would become his favorite sf device for the importation of aliens into rural Wisconsin, always his favorite venue. (In 1938, inspired by John W Campbell Jr’s editorial policy at Astounding, Simak began to produce such stories as “Rule 18” (July 1938 Astounding) and “Reunion on Ganymede” (November 1938 Astounding). He swiftly followed with his first full-length novel, Cosmic Engineers (February-April 1939 Astounding; rev 1950), a galaxy-spanning epic in the vein of E.E. Smith and Edmond Hamilton. While continuing to write steadily for Campbell, his work gradually became identifiably Simakian – constrained, intensely emotional beneath a calmly competent genre sf surface.

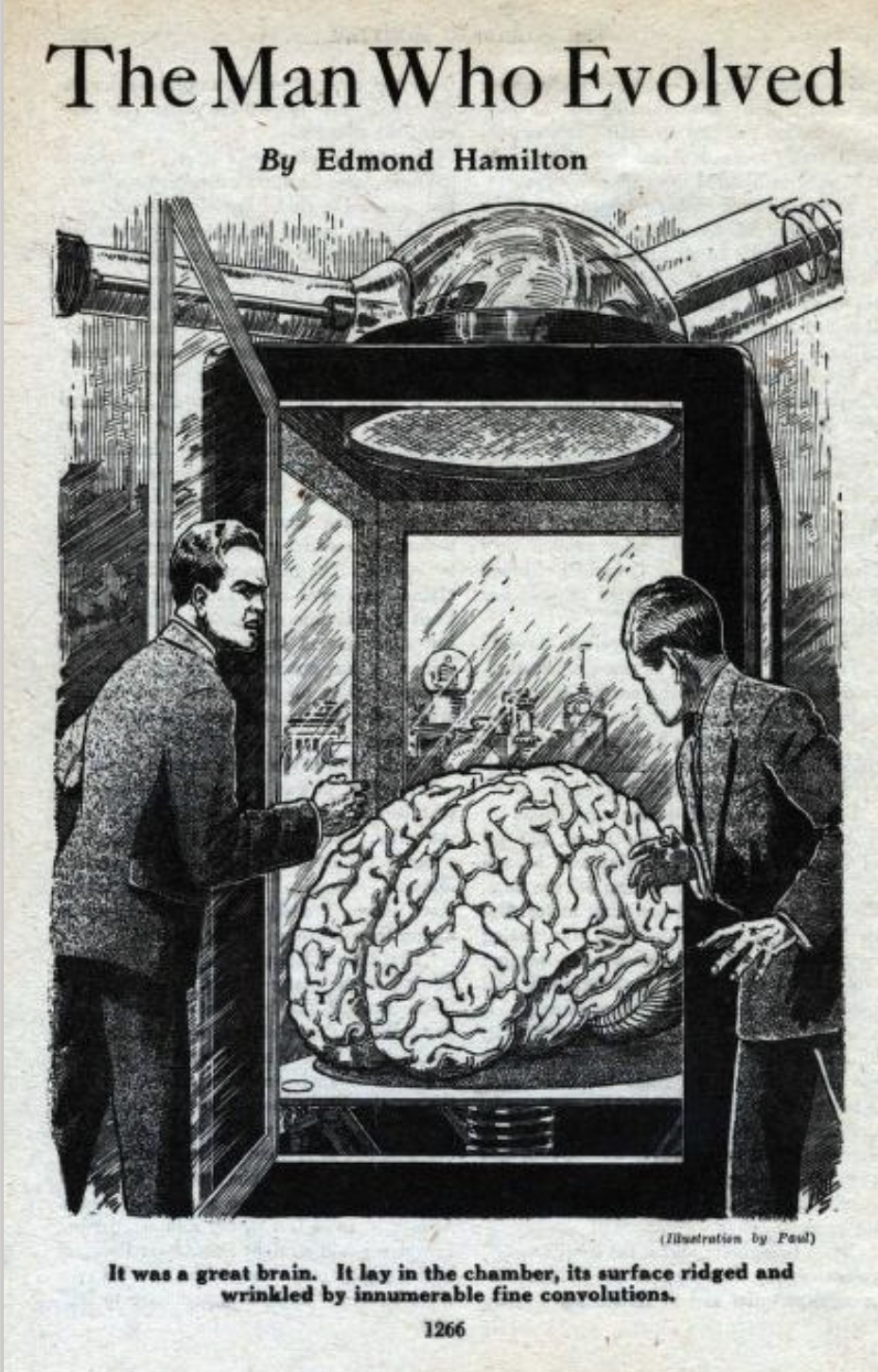

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Man Who Evolved.” Often reprinted. Hamilton was a stalwart of the early pulps, a pioneer of space opera. He was trying to move away from space opera at this point. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.) Note that The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction (2010, ed. Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Arthur B. Evans, Joan Gordon, Veronica Hollinger, Rob Latham, Carol McGuirk) jumps all the way from Forster’s “The Machine Stops” (1909) to this story — nothing from the teens or twenties!

- Egon Friedell’s “Is the Earth Inhabited?” Austrian story — a series of seven postulates by intergalactic professors demonstrating that it is impossible for life to exist on planet Earth. The story is a good example of the sort of mocking irony that was encouraged by editor Karl Krauss and the writers associated with his journal Die Fackel (The Torch). And it is representative of the sort of anomie that impelled Friedell to commit suicide in the face of the rise of Nazism. Collected in The Black Mirror (Wesleyan).

- Erle Stanley Gardner’s “The Human Zero.” Novella about a supercriminal. Not very good, one hears.

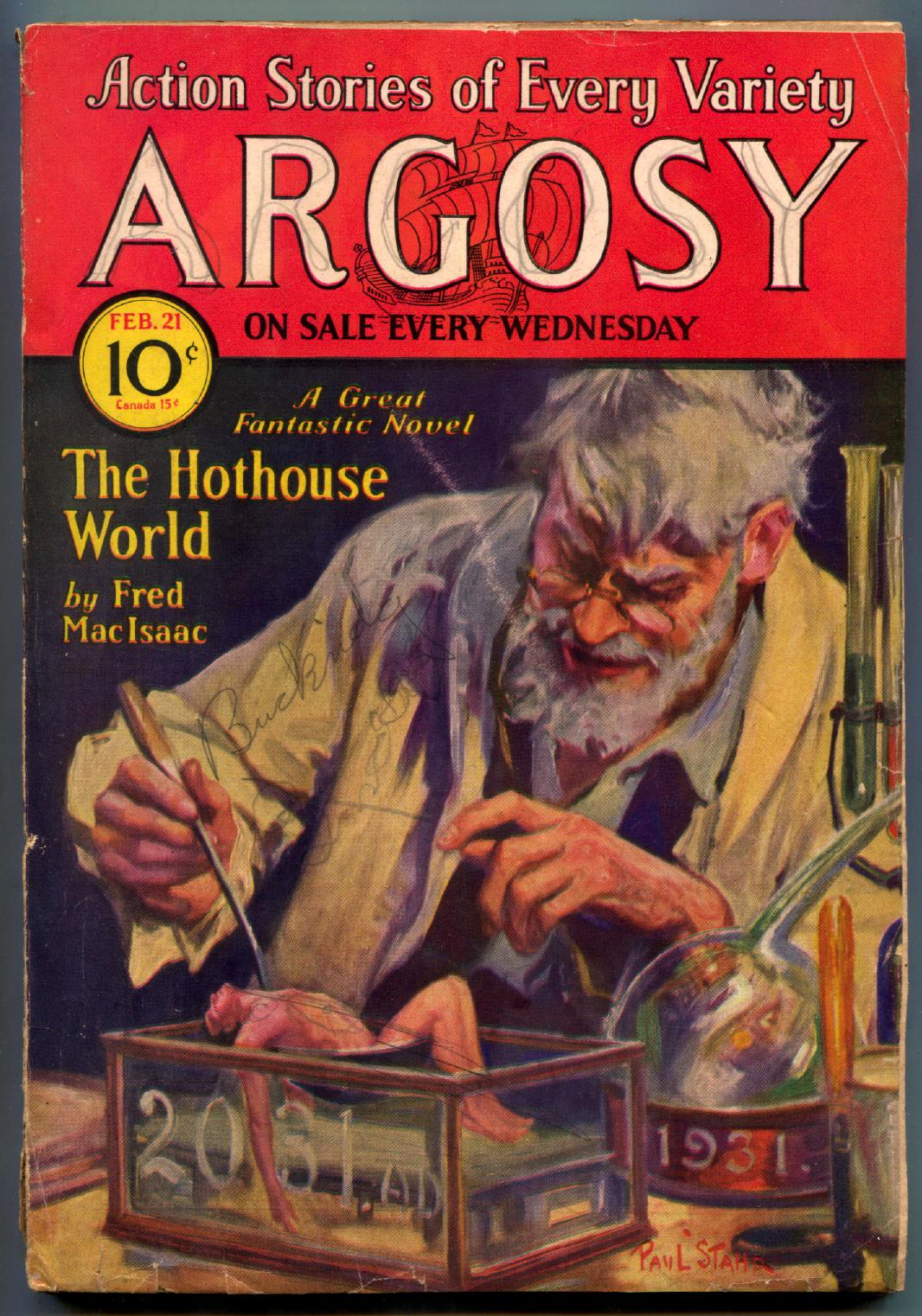

- Fred MacIsaac’s The Hothouse World (21 February-28 March 1931 Argosy; 1965 in book form) awakes its protagonist from suspended animation into the insanely restrictive ruined-Earth world of 2051 CE – its inhabitants pent in a single domed keep – which he liberates once it is demonstrated that the air outside can again be breathed.

- Ellen Olney Kirk’s A Woman’s Utopia, by a Daughter of Eve. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mrs. Norman Lee’s A Woman — or What? See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mrs. G. Stuart’s On the Shores of the Infinite. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

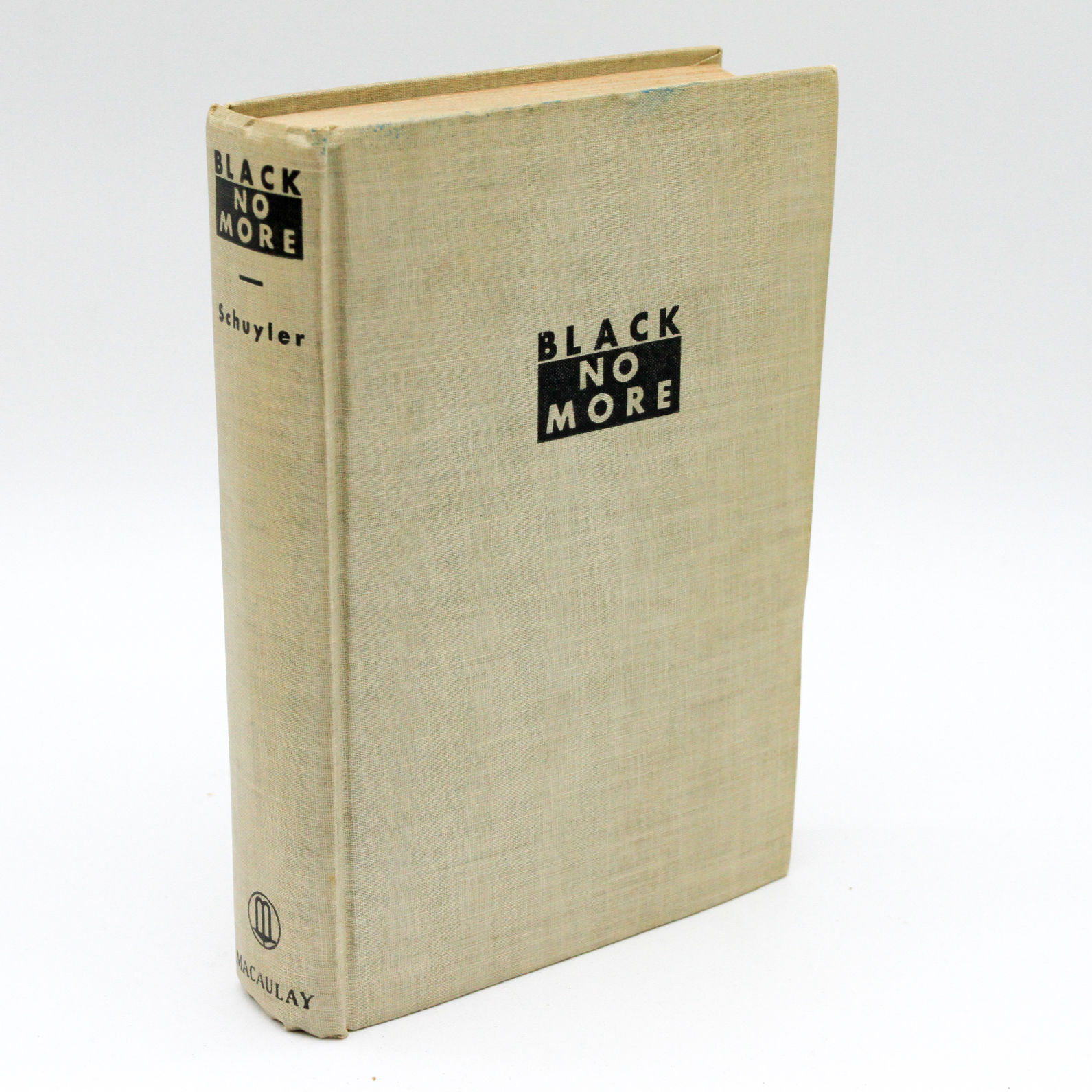

- George Schuyler’s Black No More: Being an Account of the Strange and Wonderful Workings of Science in the Land of the Free, A.D. 1933-1940. Schuyler was an African American author. This satire features the invention of a cosmetic treatment that can bleach Blacks permanent white; the protagonist, now white (Schuyler scathingly mocks any understanding of race as being defined by anything more significant than external circumstances), becomes a leading member of the Ku Klux Klan.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Superman of Dr. Jukes” (Wonder Stories, November 1931) once again features a criminal rather than a scientist as protagonist. “Killer Mike” is a hitman for the mob who ends up on the wrong side of his boss “The Big Shot”. He flees into the world of hobos, where he subsists until Dr. Jukes offers him work on an experiment. For money and lodgings, “Killer” is injected with serum occasionally until several weeks pass. The experiment over, Jukes leaves the killing of the specimen to an underling. Fortunately for “Killer” he had snuck into the lab the night before and accidentally mixed up the bottles. Instead of a lethal injection, he is given more serum, making him super-fast and super-strong. The gunmen are helpless to stop the superman from coming into the big Shot (Frazzini)’s own lair and taking him. Mike and his victim are chased by mobs of thugs and police wanting the reward. Killer Mike takes them out into the desert, for the superman continues to change under the power of the serum, now seven feet tall and burning hot. Frazzini’s mind is an open book, and Mike tells him to quiet his mind. The vibrations increase and he can see another dimension, filled with beautiful places and people. But Mike has reached his climax and now begins to cool down. The magical other realm disappears and he wanders the desert out of his mind.

- Kafka’s posthumous compilation Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer: Ungedruckte Erzählungen und Prosa aus Dem Nachlas (translated into English in 1933 as The Great Wall of China and Other Pieces). The title story (written 1917) evokes an illimitable time abyss. (The recognition of deep time – the realization of truly awesome timescales – is one of sf’s staple generators of a sense of wonder.) The SFE suggests that the story has been deeply influential, almost in secret, on many sf authors.

- Gunnar Serner’s SweStölden av Eiffeltornet (The Theft of the Eiffel Tower). Incorporates speculative and imaginative elements. Swedish.

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Whisperer in Darkness” (August 1931 Weird Tales). “Wild horror stalked the Vermont hills — a story of weird fungi from the newly discovered ninth planet.” One of the handful of Lovecraft’s sf stories which are considered central to his oeuvre.

- J.M. Walsh’s Vandals of the Void. Australian author — an interplanetary thriller.

- J. Leslie Mitchell’s The Thirteenth Disciple: Being Portrait and Saga of Malcolm Maudslay in his Adventure Through the Dark Corridor (1931). An oddly desultory Lost World tale, which presents the argument that evolution could not properly be understood in Whig terms, with earlier members of the family climaxing (for the moment) in Homo sapiens being seen as prototypes to be perfected in us. This line of thought distinguishes him from Wells, and indeed from almost the whole of British Anthropology and fiction. His first sf novel.

- Jack Williamson’s “The Meteor Girl.” Early story about Einstein’s theory.

- Jack Williamson’s “The Stone from the Green Star.”

- Jack Williamson’s “Through the Purple Cloud” — parallel worlds story.

- John Hargrave’s “The Imitation Man.” Mentioned in Anatomy of Wonder. Lighthearted, telepathy.

- End of the World (French: La Fin du monde) is a 1931 French science fiction film directed by Abel Gance based on the novel Omega: The Last Days of the World by Camille Flammarion. The film stars Victor Francen as Martial Novalic, Colette Darfeuil as Genevieve de Murcie, Abel Gance as Jean Novalic, and Jeanne Brindau as Madame Novalic. The plot concerns a comet hurtling toward Earth on a collision course and the different reactions people have to the impending disaster. Scientist Martial Novalic who discovers the comet, seeks a solution to the problem and becomes a fugitive after skeptical authorities blame him for starting a mass panic.

- John W. Campbell’s “Islands of Space.” An Arcot, Morey, Wade story — the team explores space at faster-than-light speed and engaging in mighty alien wars.

- John Wyndham (John Beynon Harris)’s “Worlds to Barter” (Wonder Stories May 1931). Mentioned by Moskowitz in Seekers of Tomorrow.

- Lord Dunsany’s collection The Travel Tales of Mr Joseph Jorkens. Spoof sf explanations and premises are sometimes discernible in Dunsany’s Jorkens tales. Most of these stories were first published in magazine form, beginning with the first, “The Tale of the Abu Laheeb” (Christmas Number 1926, The Graphic), which is a missing-link tale. Like this example, some of the tall tales told by the unreliable Jorkens hint at outright sf, e.g. communication with and travel to and from Mars, and various inventions including antigravity, extraterrestrial holocausts and the Futuroscope time viewer. These tales helped focus the attention of the era’s sf and fantasy writers upon the late Victorian and Edwardian “Club Story” as a suggestive mode for sf and fantasy.

- Murray Leinster’s “The Fifth-Dimensional Catapult.”

- Michel Corday’s La Flamme éternelle (1931). Its sequel is Ciel Rose (1933). These have been translated together in one volume by Brian Stableford, as The Eternal Flame (2013).

- Miles J. Breuer’s “The Birth of a New Republic.”

- Neil Bell’s Precious Porcelain. A mad scientist generates diseased doppelganger avatars which savagely disrupt a provincial town. Hello, Invasion of the Bodysnatchers. See Anatomy of Wonder – series of experiments in evocation of alternate personalities.

- Neil Bell’s The Gas War of 1940 (1931 as Miles; vt Valiant Clay 1934 as NB). See Seventh Bowl (1930), the first in the Gas War sequence.

- Owen Johnson’s The Coming of the Amazons. See more in Anatomy of Wonder. Good humored book about the coming of female-dominated society. Moskowitz says it’s the best book about women as a ruling class. By the author of a series of books about Stover (Stover at Yale, etc.).

- Ralph Milne Farley’s “The Time Traveler.” Time travel story by prolific pulp sf writer.

- S.S. Held’s La Mort du fer (The Death of Iron). Serge-Simon Held was a French science fiction author known for the 1931 environmentalist novel La Mort du Fer. Translated by Fletcher Pratt, published in Wonder Stories in 1932. The novel is set in northern France, and concerns a mysterious “disease” which attacks iron. This eventually ushers in an “after-metal” world, in which plant life flourishes.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Earth Owners.” One of the first examples of a theme later to be enormously popular in sf: that Earth is already invaded and we are manipulated by aliens in disguise. Charles Fort formulated this paranoid insight pithily: “We are property.”

- Philip Wylie’s The Murderer Invisible. Brilliant scientist discovers a chemical formula to render matter invisible and utilizes his secret in an attempt to rule the world. A tale inspired by Wells’s The Invisible Man (1897), which served as the basis for Universal Studio’s first attempts to create a shooting script for the Wells novel (the filmed version of The Invisible Man was based on the original tale from a screenplay by R C Sherriff).

ALSO: Edison dies; Urey discovers deuterium. Wilkins captains Nautilus submarine under the Arctic Ocean. Planck’s Positivism and the Real Outside World. Mosley forms fascist UK political party. Faulkner’s Sanctuary. Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key, Nathanael West’s The Dream Life of Balso Snell, Hergé’s Tintin en Amérique . Dali’s Persistence of Memory. Chaplin’s City Lights, James Whale’s Frankenstein with Karloff.

Julian Huxley’s “What Dare I Think?” speculates on future developments — including a designer drug that would one day be taken by millions — on which his brother Aldous will expand in Brave New World.

Lo! is the third published nonfiction work of the author Charles Fort (first edition 1931). In it he details a wide range of unusual phenomena. In the final chapter of the book he proposes a new cosmology that the earth is stationary in space and surrounded by a solid shell which is “not unthinkably far away”.

Of Fort’s four books, this volume deals most frequently and scathingly with astronomy (continuing from his previous book New Lands). The book also deals extensively with other subjects, including paranormal phenomena, which were explored in his first book, The Book of the Damned. Fort is widely credited with having coined the now-popular term “teleportation” in this book, and here he ties his previous statements on what he referred to as the Super-Sargasso Sea into his beliefs on teleportation. He would later expand this theory to include purported mental and psychic phenomena in his fourth and final book, Wild Talents.

Lo! takes its derisive title from what Fort regarded as the tendency of astronomers to make positivistic, overly precise, and premature announcements of celestial events and discoveries. Fort portrays them as quack prophets, sententiously pointing towards the skies and saying “Lo!”.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin