RADIUM AGE: 1923

By:

September 26, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The year 1923, in my periodization scheme, marks the end of the cultural decade known as the “Nineteen-Teens.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1923 (and 1924) as cusp years during which the Teens end and the Twenties begin.

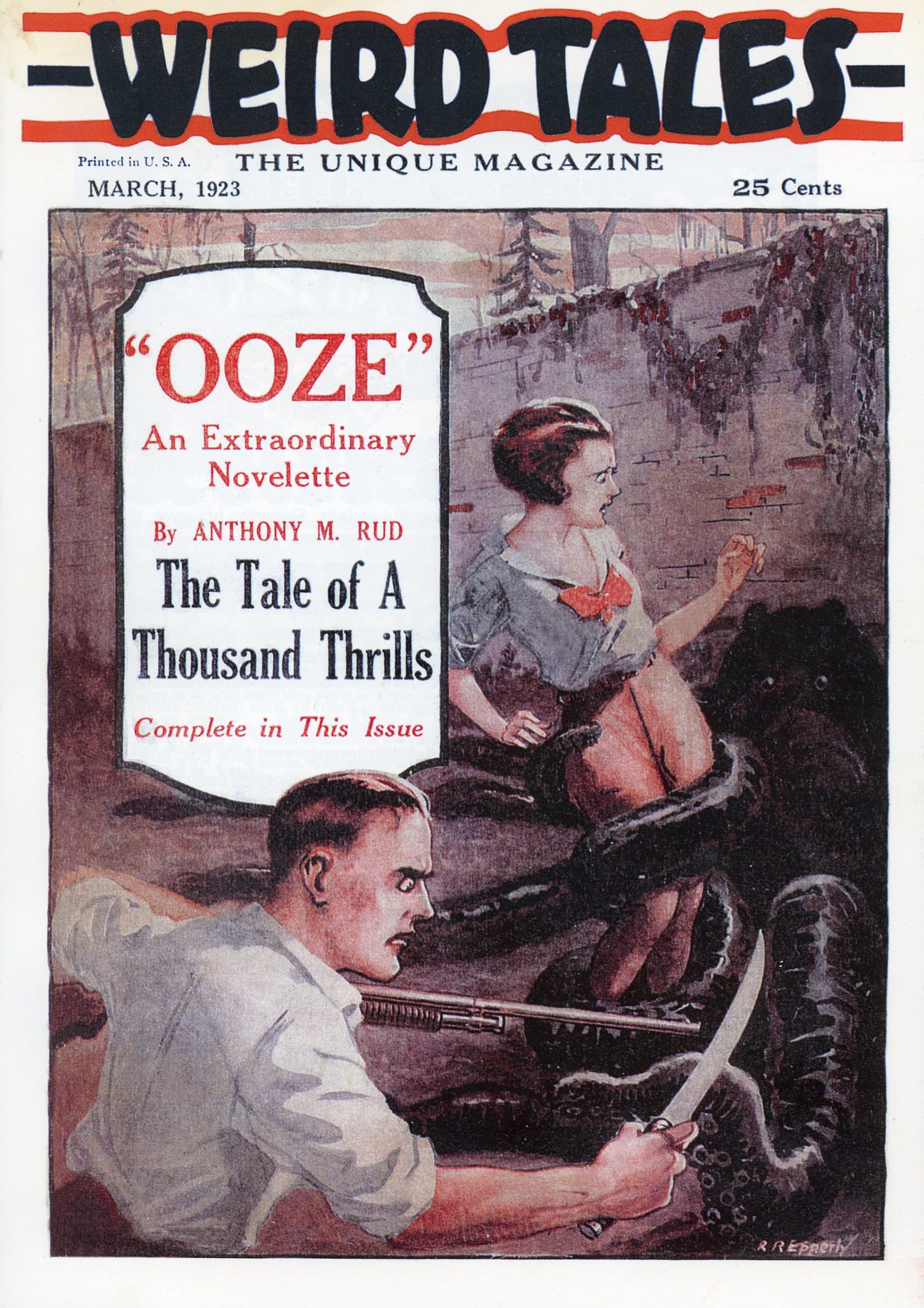

Weird Tales debuted in March 1923, providing a venue for fiction, poetry, and non-fiction on topics ranging from ghost stories to alien invasions to the occult. It was the first magazine to be primarily associated with fantasy and science fiction. See 1924.

Also in 1923: Gernsback devotes an entire issue of Electrical Experimenter to “scientific fiction.”

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1923, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: PARALLEL UNIVERSE | SPACE TRAVEL | WEIRD (describing supernatural horror (often in weird fiction, weird tale, etc. — in title of Weird Tales)

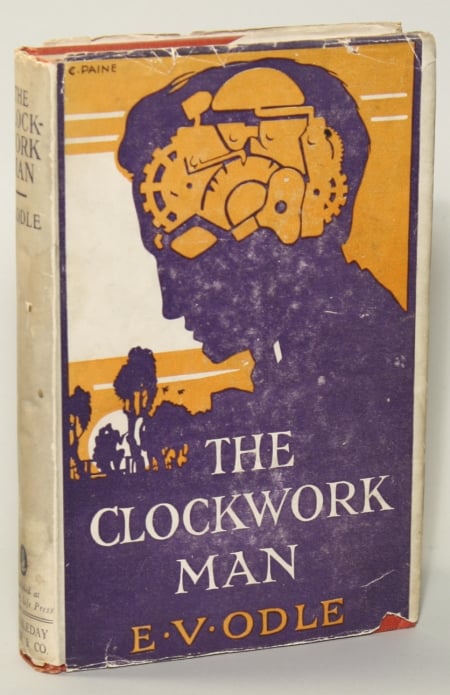

- E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man (1923). Years from now, advanced beings known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these marvelous devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live perfectly regulated lives. However, if one of these devices should ever go awry, a “clockwork man” from the future might turn up in the 1920s, perhaps at a cricket match in a small English village. Considered the original cyborg novel, and perhaps the original singularity novel too. “Odle’s ominous, droll, and unforgettable The Clockwork Man is a missing link between Lewis Carroll and John Sladek or Philip K. Dick,” says Jonathan Lethem. “Considered with them, it suggests an alternate lineage for SF, springing as much from G.K. Chesterton’s sensibility as from H.G. Wells’s.” Fun fact: Rumors that “E.V. Odle” was a pen name for Virginia Woolf are amusing, but unfounded. Edwin Vincent Odle (1890–1942) was a writer who lived in Bloomsbury, London during the 1910s. From 1925–35, he was editor of the British short-story magazine The Argosy. Reissued in 2022 by MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series with an Introduction by Annalee Newitz.

- J.J. Connington’s Nordenholt’s Million (1923). As denitrifying bacteria inimical to plant growth spread around the world, causing agricultural blight, Jack Flint is invited to become director of operations at a huge survivalist colony located in England’s Clyde Valley. Flint discovers that his employer, the ruthless plutocrat Nordenholt, has blackmailed the country’s politicians in order to establish his stronghold, of which he becomes dictator in all but name. What’s more, Nordenholt’s henchmen purposely wreck what remains of British civilization, leading to scenes of horrific mass violence and agony; and the colony’s workers are treated like serfs. The plant-killing plague ends… but Nordenholt’s collectivized serfs refuse to work, blow up the factories on which their fragile community depends, and join weird religious cults! The author, it seems, was as worried about the Soviet Revolution as he was about right-wing politicians and rapacious businessmen eager to use any disaster as an excuse to dispense with democracy, liberty, and justice. Fun fact: Connington was the pseudonym of Alfred Walter Stewart, the British chemist who coined the term isobar as complementary to isotope. Reissued in 2022 by MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series, with an introduction by Matthew Battles and an afterword by Evan Hepler-Smith.

- Arpad Ferenczy’s The Ants of Timothy Thummel. Ferenczy is the Hungarian author of the German-language proto-sf novel Timotheus Thümmel und seine Ameisen (1923; trans anon as The Ants of Timothy Thümmel 1924), a Satire featuring a race of ants in central Africa whose Intelligence exceeds that of humans, and who engage in a kind of world-spanning Great Ant War with surrounding tribes of ants; these events may be presumed to have happened aeons earlier, as the only record of the war is to be found in a hieroglyphic tablet which itself refers to events in the deep past.

- Some of the poems in Vachel Lindsay’s Going to the Sun are of sf interest.

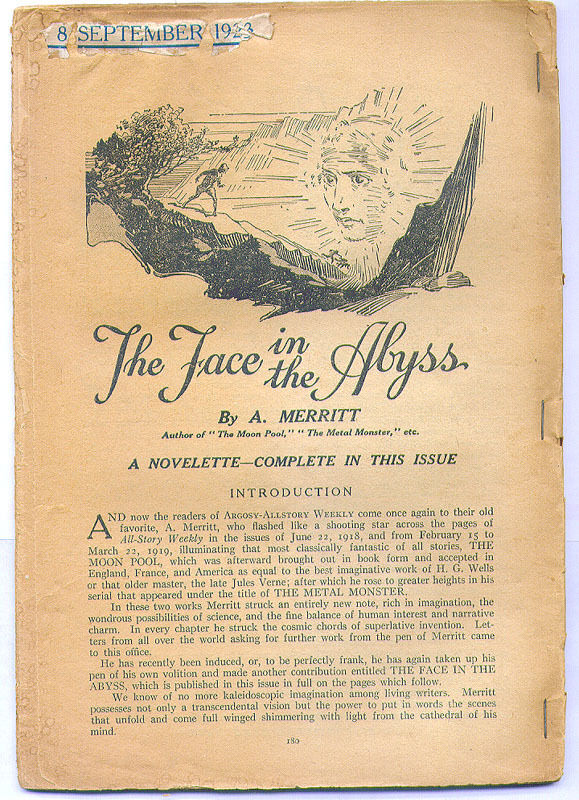

- A. Merritt’s The Face in the Abyss (serialized in Argosy All-Story Weekly). The original novella, some say, is superior to the 1931 novel version.

- A. Merritt’s “The Pool of the Stone God.”

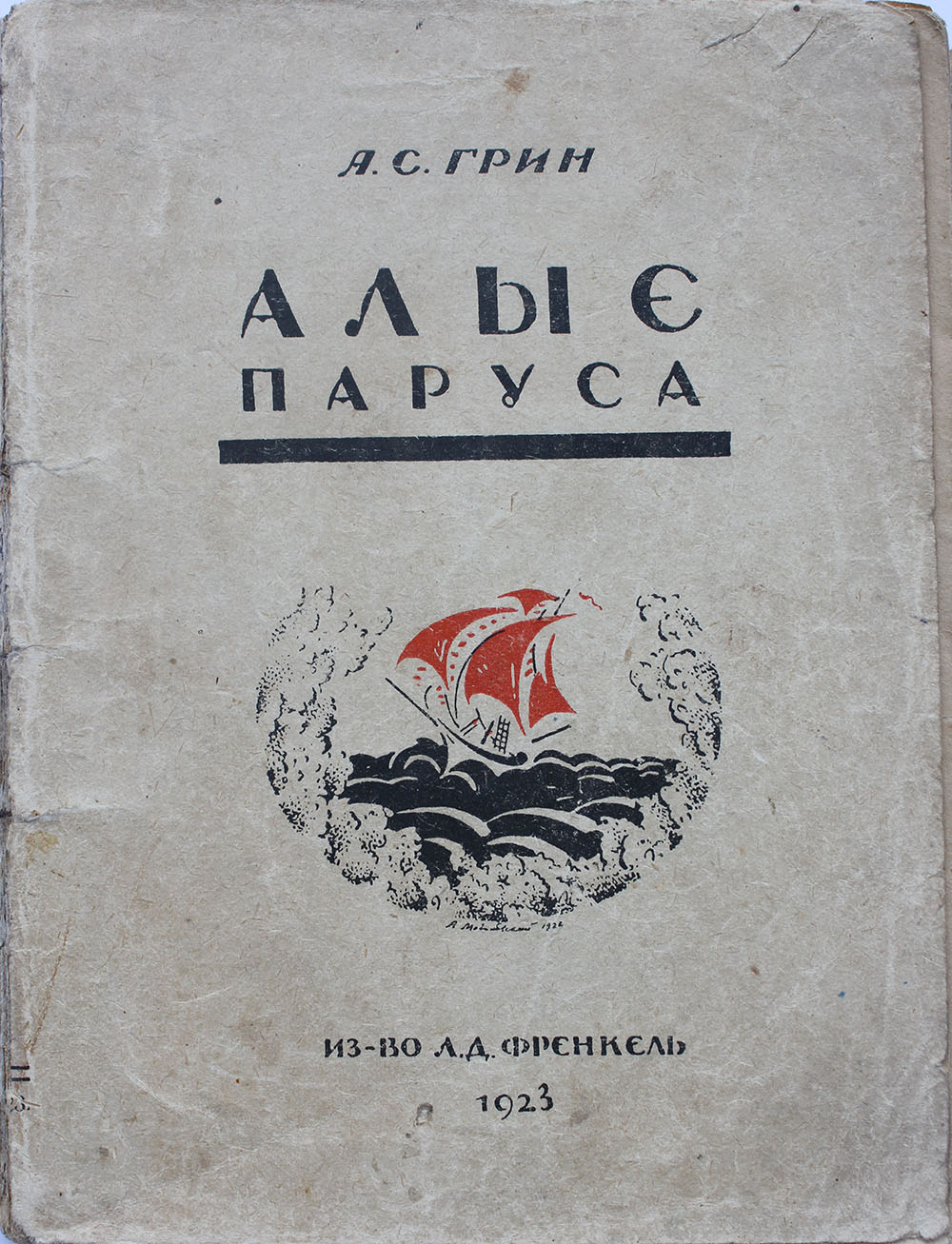

- Alexander Grin’s Alyie parusa [“Scarlet Sails”]. Grin, a Russian author, began his writing career after his imprisonment and exile after the 1905 Revolution. His romances set in a parallel world fed a strong appetite in Russia, especially after the 1917 Revolution when high fantasy was taboo, and they were printed in millions of copies. Containing many fantastic elements they include the stories in Shapka-nevidimka [“The Hat of Invisibility”] (coll 1908), the novels Alyie parusa [“Scarlet Sails”] (1923), Blistaiushchii mir [“The Shining World”] (1923), Doroga nikuda [“Road Nowhere”] (1930) and others.

- Alexander Grin’s Blistaiushchii mir [“The Shining World”]

- Austin Hall’s “Hop o’ My Thumb.” Another microcosmic romance. Called Hall’s most interesting solo work.

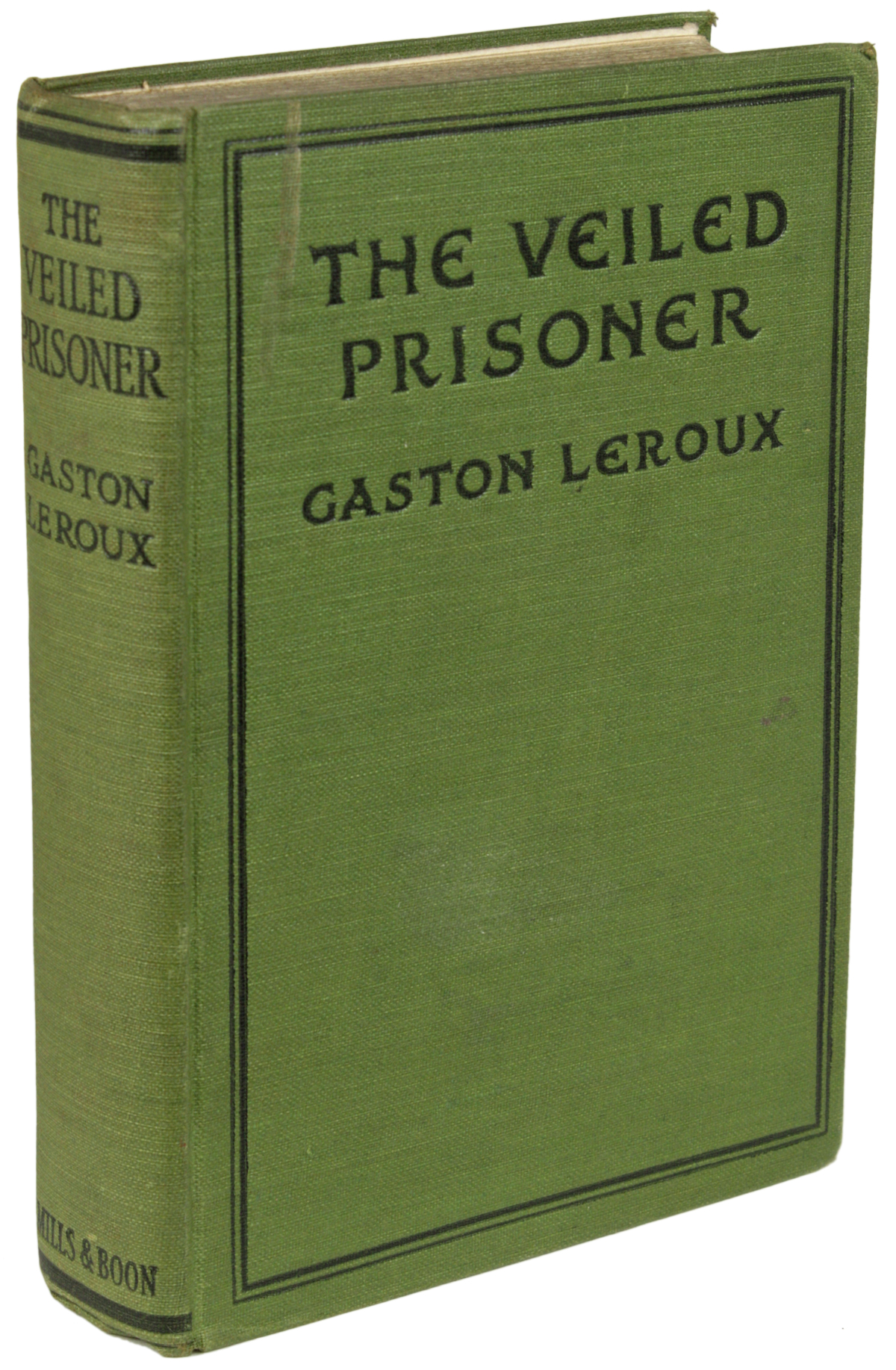

- Gaston Leroux‘s The Veiled Prisoner. Translated by Hannaford Bennett (1923). Science fiction novel of adventure and intrigue set in the first world war and featuring a super-submarine commanded by a mysterious person obviously inspired by Captain Nemo. Includes the concept of undersea trench warfare.

- Christopher Blayre (Edward Heron-Allen)’s The Cheetah-Girl (1923 chap). Kind of an amazing story — seems almost too raunchy and transgressive to publish today. Reminds me a bit of Octavia Butler.

- Claude Farrère’s Contes d’outre et d’autres mondes (Tales of Beyond and Other Worlds). Some of the stories in this collection (untranslated?)are proto-sf.

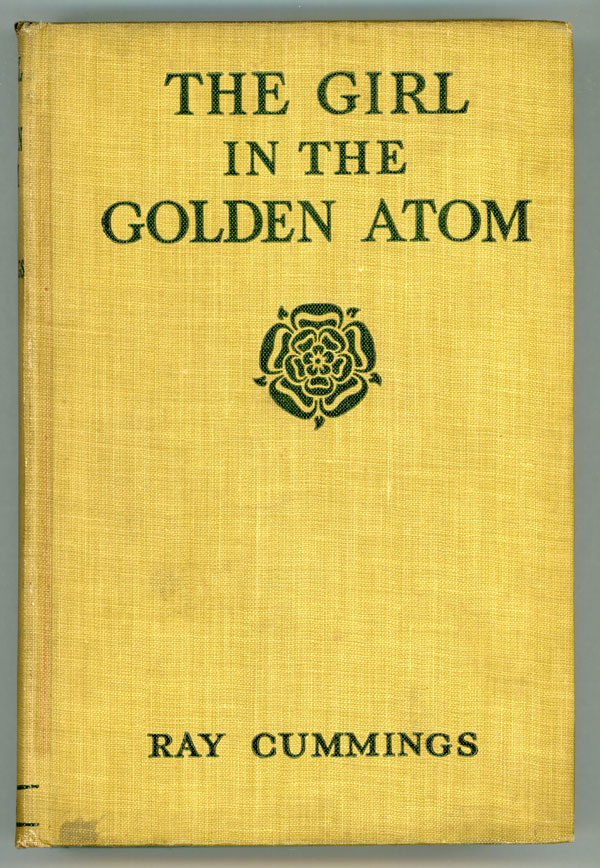

- Ray Cummings’s The Girl in the Golden Atom. “The Girl in the Golden Atom,” Cummings’ first published story, appeared in the 15 March 1919 issue of All-Story Weekly. It was an instant success and was followed by a sequel, “People of the Golden Atom,” published 24 January–28 February 1920. The two stories are here collected as the author’s first book. See 1919.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “Growth” — about giantism.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s “The Moon Maid” (stories May 1923-September 1925 Argosy All-Story Weekly as “The Moon Maid” [5 May-2 June 1923], “The Moon Men” [21 February-14 March 1925] and “The Red Hawk” [5-19 September 1925]. Describes a civilization in the hollow interior of the Moon and a future invasion of the Earth. As a fixup in 1926, and there were 1960s versions too.

- Francis Stevens’s “Sunfire” (July-September 1923 Weird Tales). A Merritt-esque story of a lost civilization in Brazil. Ashley suggests this is one of the author’s weaker works, probably rejected by the Munsey magazines.

- George Allan England’s “The Thing from – ‘Outside'”. A creature that may hail not merely from off-world but from a dimension “outside the universe” stalks an expedition in the Canadian wilderness. A science-fictional updating of Blackwood’s 1910 horror tale “The Wendigo,” the story appeared in the April 1923 issue of Hugo Gernsback’s magazine Science and Invention. Ashley says: England had by now passed his peak in the Munsey magazines but still a better writer than any of Gernsback’s contributors, so this was one of the best stories that Science and Invention published

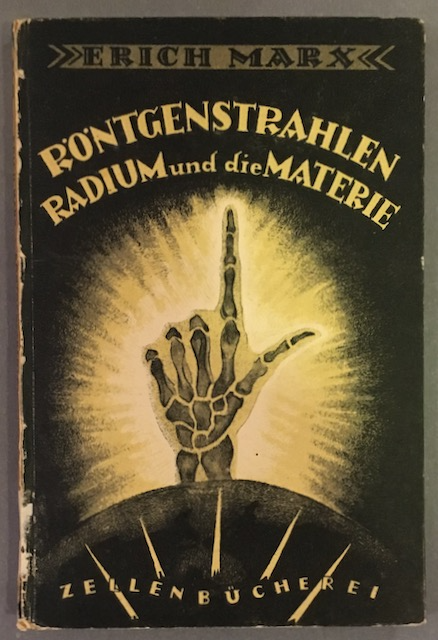

- Gertrude Atherton’s Black Oxen. Women (only) are rejuvenated by X-rays directed to the gonads. The novel’s sexual implications caused a scandal.

- John Hargrave’s Harbottle. A bitter Wellsian novel of ideas.

- John Martin Leahy’s “Draconda” (serial). Haggard-esque lost race on Venus, not very well written but fondly remembered. In Weird Tales.

- Gilbert Collins’s The Valley of Eyes Unseen — Lost Race adventure. A Tibetan hidden valley inhabited by scientifically advanced descendants of Alexander the Great’s Greeks, from whom the protagonist eventually escapes by purloining one of their inventions, mechanical wings. Michael Dirda tells me he likes it.

- Otis Adelbert Kline’s “The Thing of a Thousand Shapes.” Kline’s debut – in Weird Tales.

- P. Anderson Graham’s The Collapse of Homo Sapiens. Time traveler visits England two hundred years in the future. English civilization has been destroyed by wars with socialists and Blacks. The few survivors live in the woods and cannot believe that scientific and mechanical aids ever existed. Said to be one of the better awful warning stories published in Britain between the World Wars. Sounds racist!

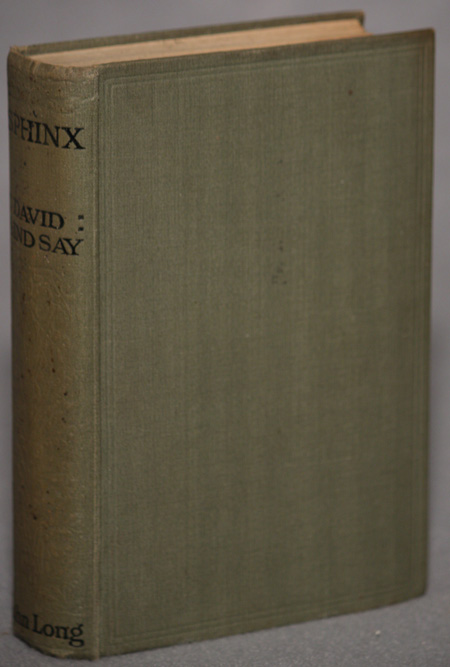

- David Lindsay’s Sphinx. Places muted metaphysical images of the same type as those found in the author’s A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) and THE HAUNTED WOMAN (1922)] in a conventional domestic drama. A hapless young man becomes entangled with two women while trying to perfect a machine to record the deep, unremembered dreams that contain the hidden truth of human existence.” “SPHINX comes closer to traditional science-fiction than anything else Lindsay was to write.” – Wolfe. “Most critics have dismissed SPHINX as a failure, but I find it curiously fascinating.” – Bleiler.

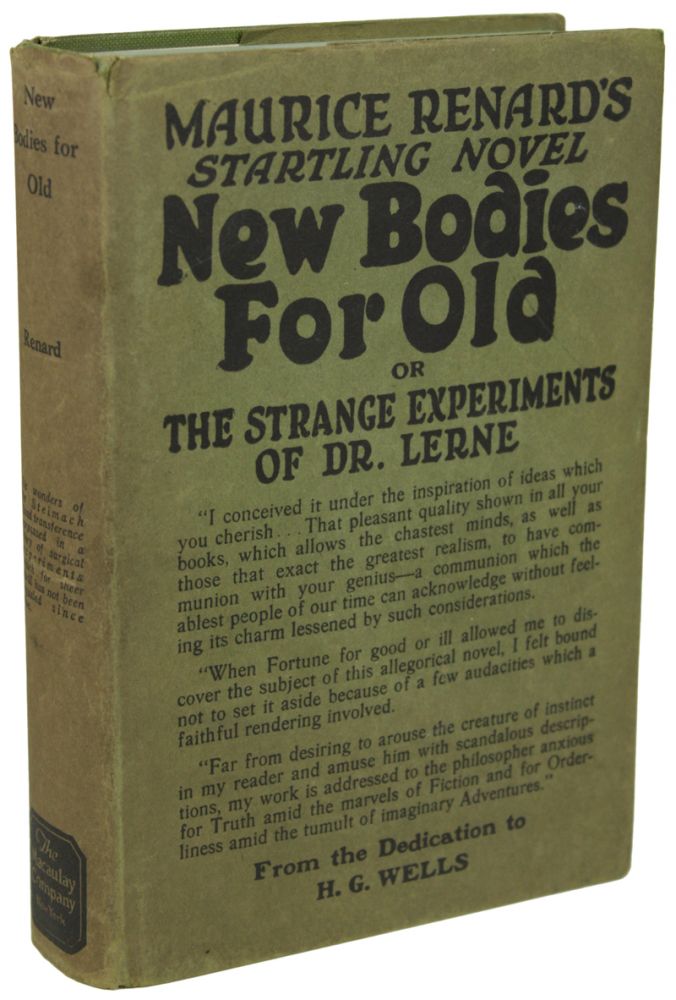

- Maurice Renard’s New Bodies for Old. The author’s first and best novel, first published in 1908 as LE DOCTEUR LERNE. See 1908.

- Théo Varlet and André Blandin’s Timeslip Troopers. This title added by Brian Stableford.

- Albino Coutinho’s Brazil – A Liga dos planetas [“The League of Planets”]. Features space flight to utopian Venus and Mars.

- Ronald Knox’s Memories of the Future: Being Memories of the Years 1915–1972, Written in the Year of Grace 1988 by Opal, Lady Porstock Combines a parody of the current autobiographies of women of fashion with a gentle satire on current whims — educational, medical, political and theological.

- G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s “The Man from the Atom.” Wertenbaker was 16 at the time. He was Gernsback’s first important discovery.

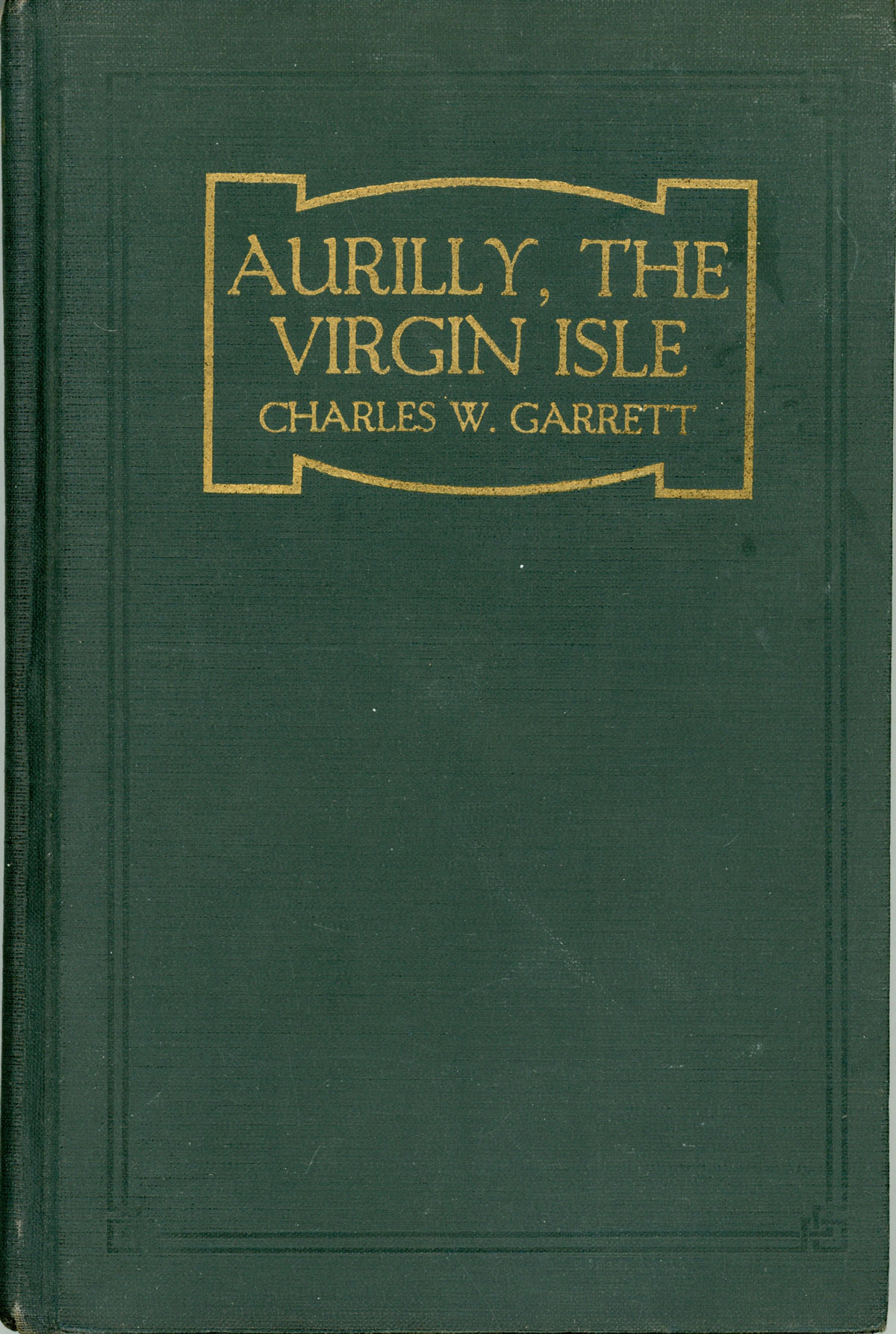

- Charles W. Garrett’s Aurilly. Eccentric science fiction novel in which a planetoid strikes Earth somewhere in the North Pacific causing a giant tidal wave and the emergence of an island some 400 miles long parallel to the Aleutians with rich gold deposits that, following exploitation, ultimately disrupt the world’s economy.

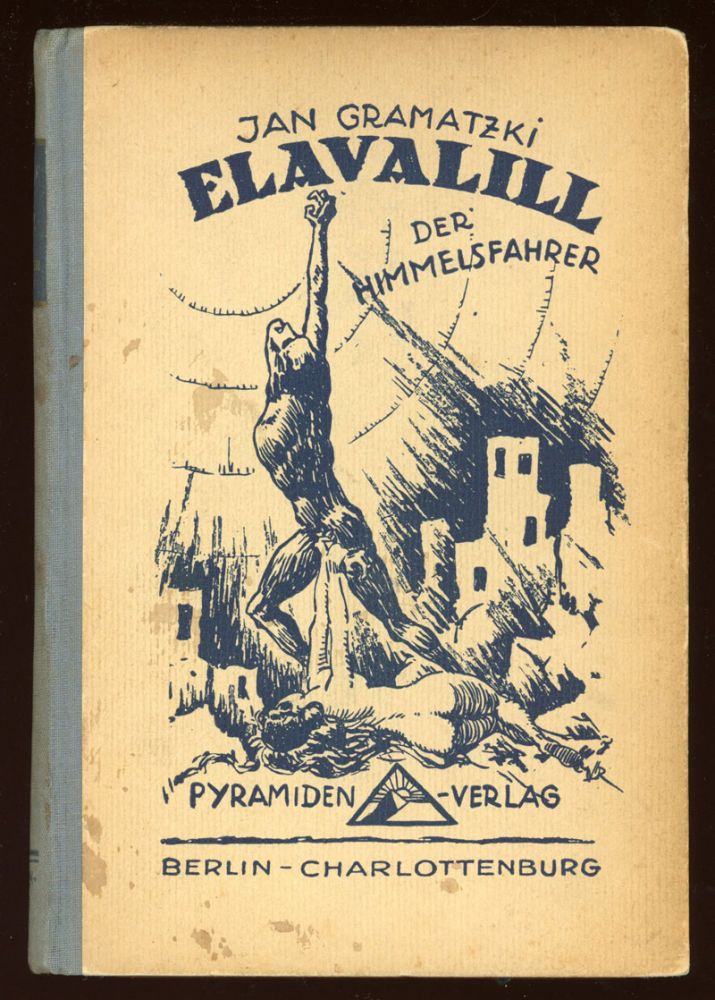

- Jan Gramatzki’s Elavalill. A novel of super science in which a German astronomer and an old Norwegian scientist who has invented “Elavalill” travel in a space ship to Venus. Meanwhile, a misanthropic inventor with an earthquake machine attacks European cities. After the destruction of Paris, Germany is attacked by the French and Poles — who suspect the Germans are responsible for the artificially created earthquakes. Germany is in chaos. After a few years the astronauts return from Venus and the earthquake machine breaks down. “Jan Gramatzki” was probably physicist Hugh Ivan Gramatzki (1882-1957). Gramatzki also wrote DER KRISTALL (1917), an occult novel about the search for the philosopher’s stone.

- Nina Murnie Doney’s My Life on Eight Planets, or A Glimpse of Other Worlds. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Laura Shellabarger Hunt’s Ultra: A Story of a Pre-Natal Influence. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- H. Alfarata Chapman Thompson’s Idealia, a Utopian Dream; or, Resthaven. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

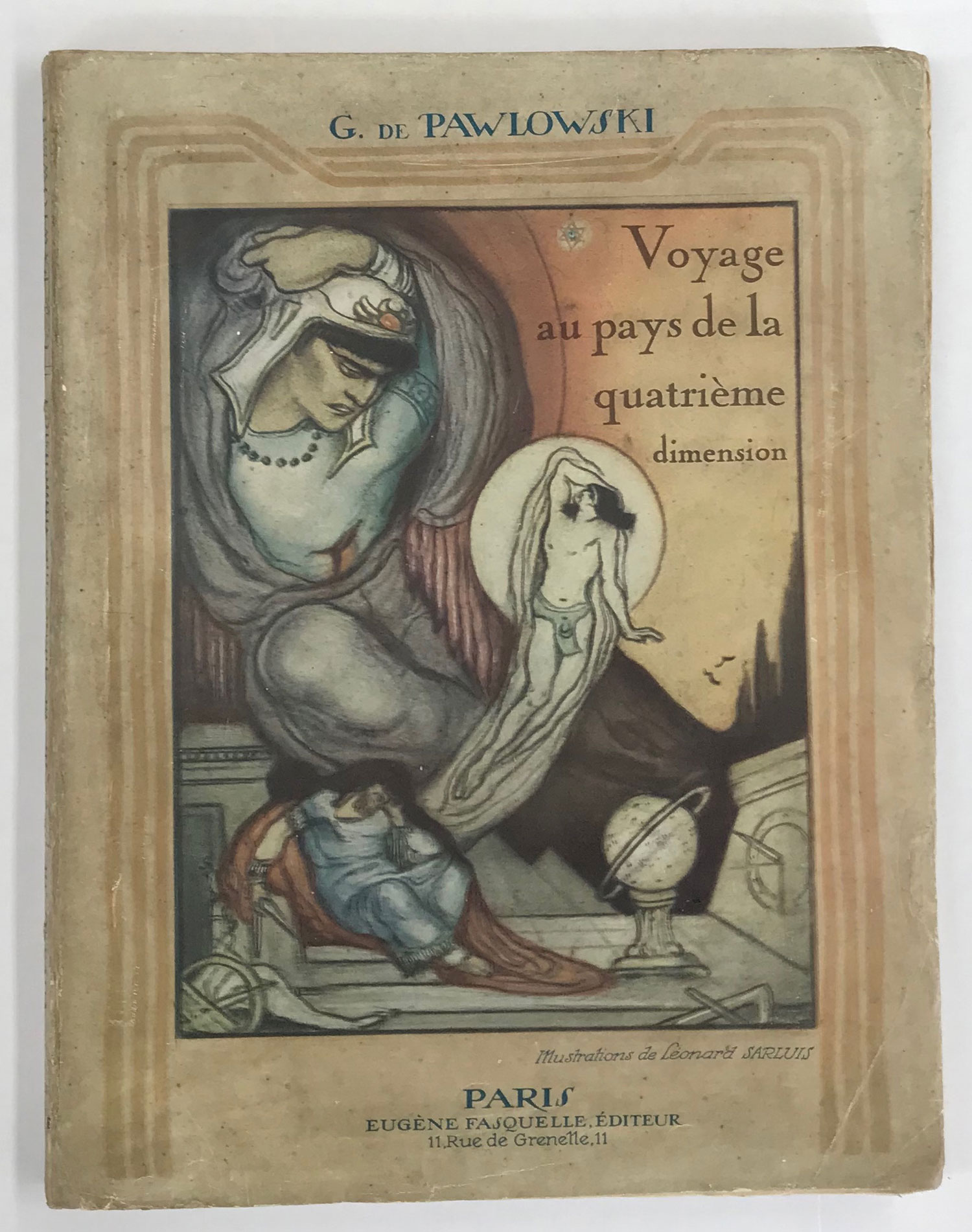

- G. Pawlowski’s Voyage au Pays de la Quatrieme Dimension. A famous anti-realistic roman de l’Idee, first published in 1912. “The new material added to the body of the text in the 1923 edition consisted of additional pieces that had appeared in COMOEDIA between 1912 and 1914 — Pawlowski was conscripted thereafter for the duration of the Great War to serve as an engineer in the ‘auto-service’ and had to give up the editorship of the magazine. The new chapters were inserted at various points in the text, according to their approximate internal chronology — many of them, inevitably, in the relatively dour section dealing with the present day and the supposed development of the collective consciousness he calls ‘the Leviathan'” (Stableford). Stableford calls it remarkable.

- H.G Wells’s Men Like Gods. The author’s second major Utopian fantasy and, according to some critics, his best. “Three carloads of Earthlings, accidentally transported into an anarchistic ‘Utopia’ based on science and rationalistic social planning, react with the violence and bigotry which the author regards as characteristic of capitalism.” — Survey of Science Fiction Literature

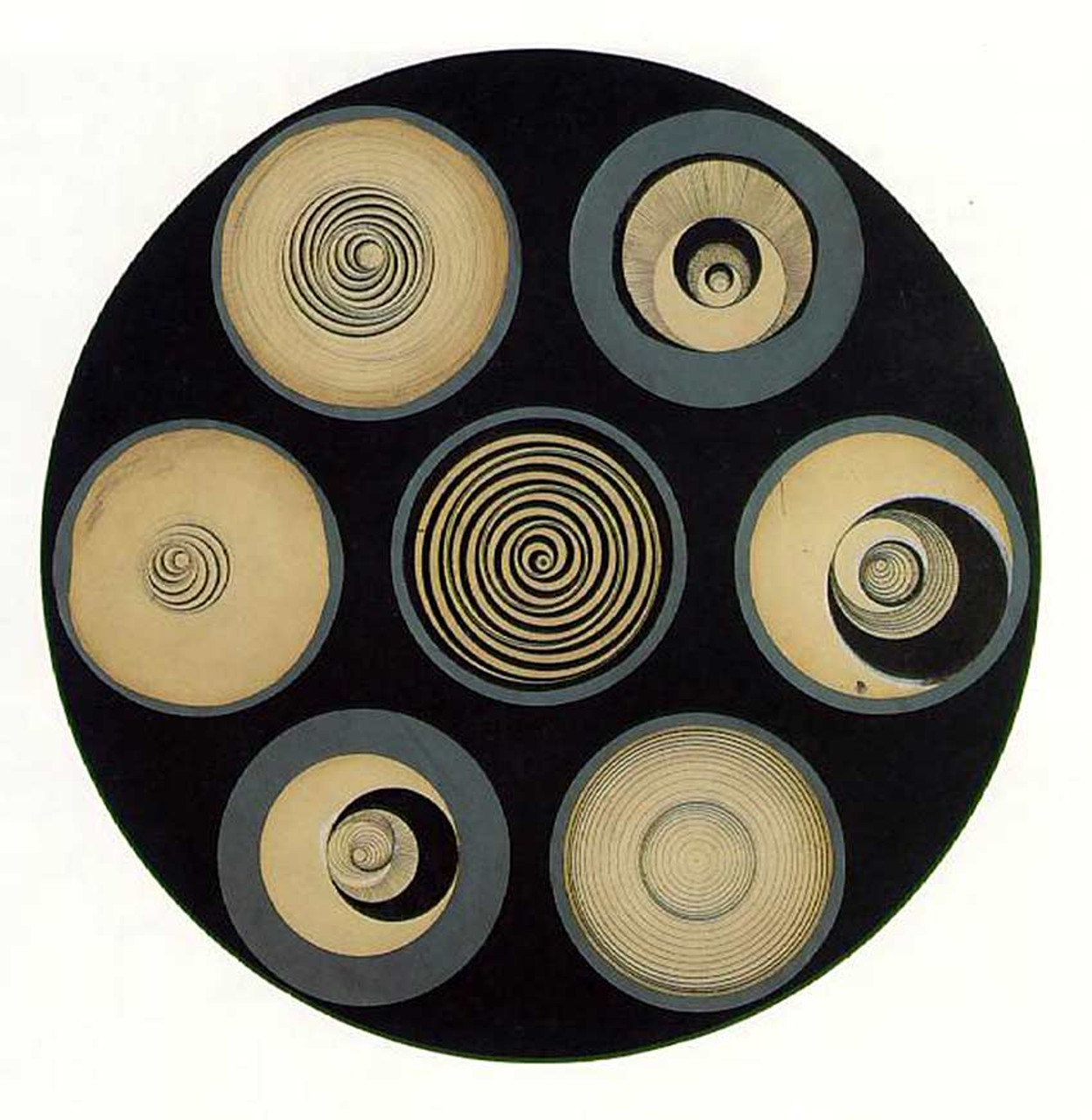

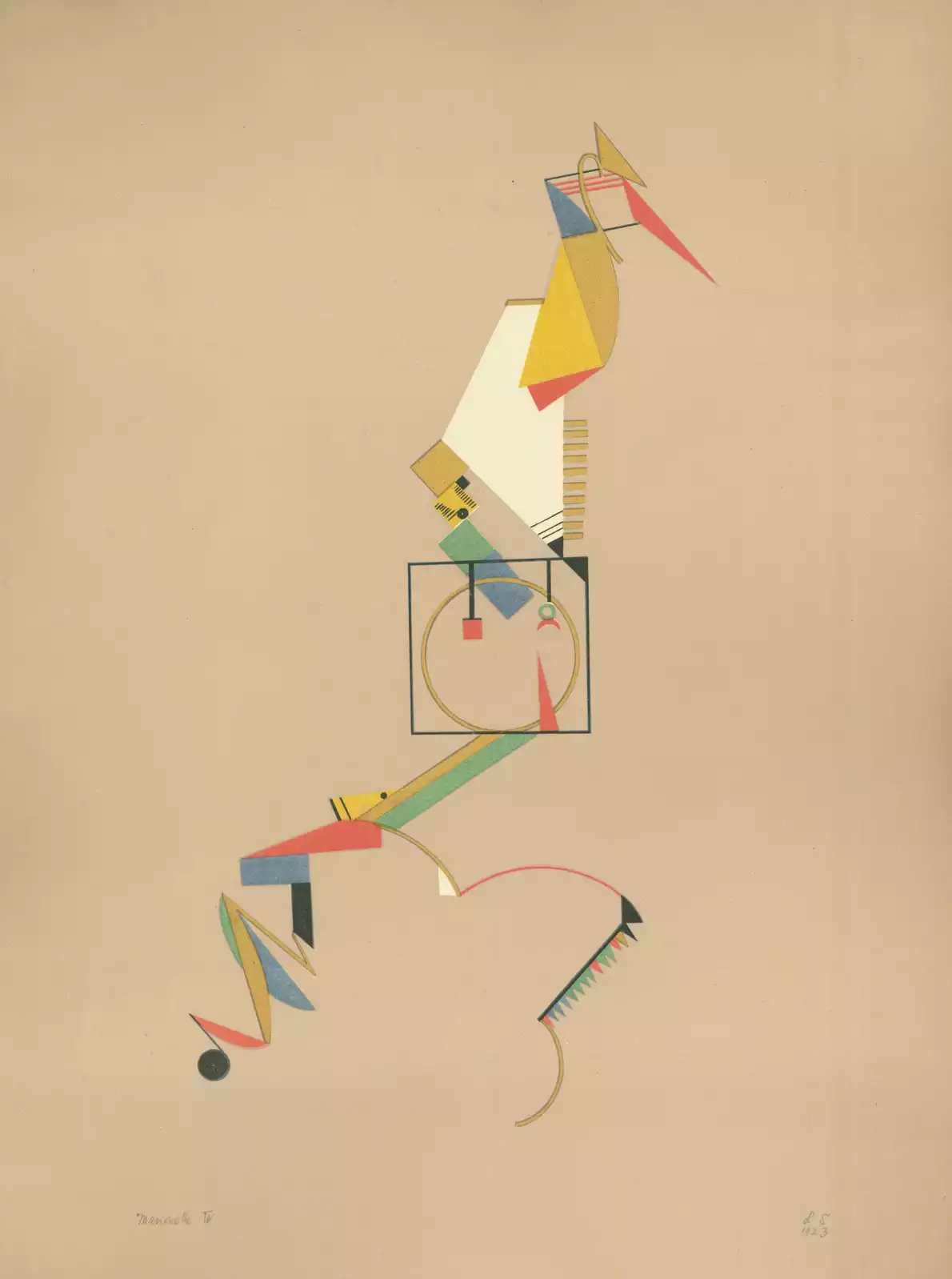

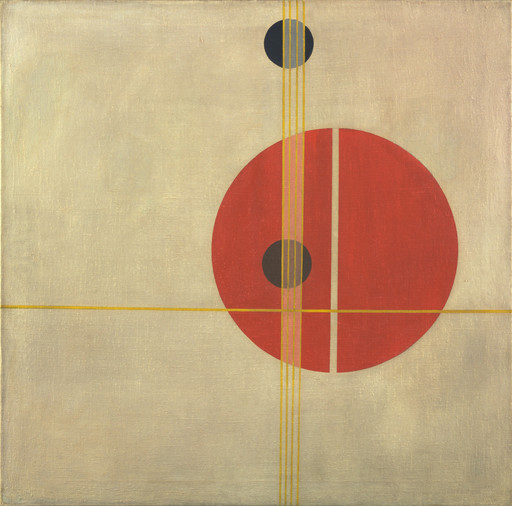

In the early 1920s, Ivan Kliun painted a series of works that he named “Cosmic Images”. One of these “images” is the painterly composition “Red light, spherical construction”. The painting reflects the attraction of many artists of the Russian Avant-garde for theories on astronomical phenomena, their interest in the future conquest of space and the understanding of the nature of the universe.

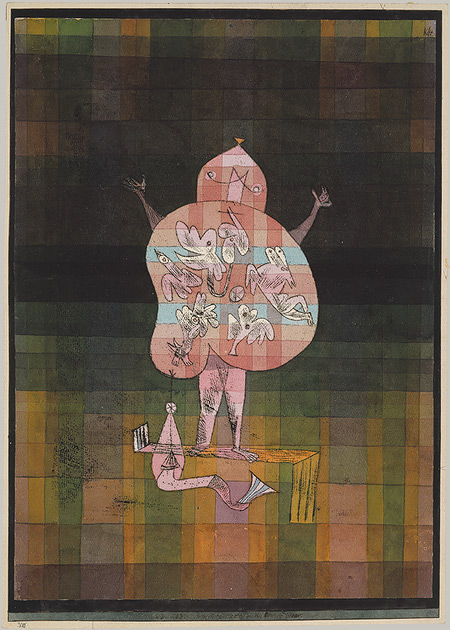

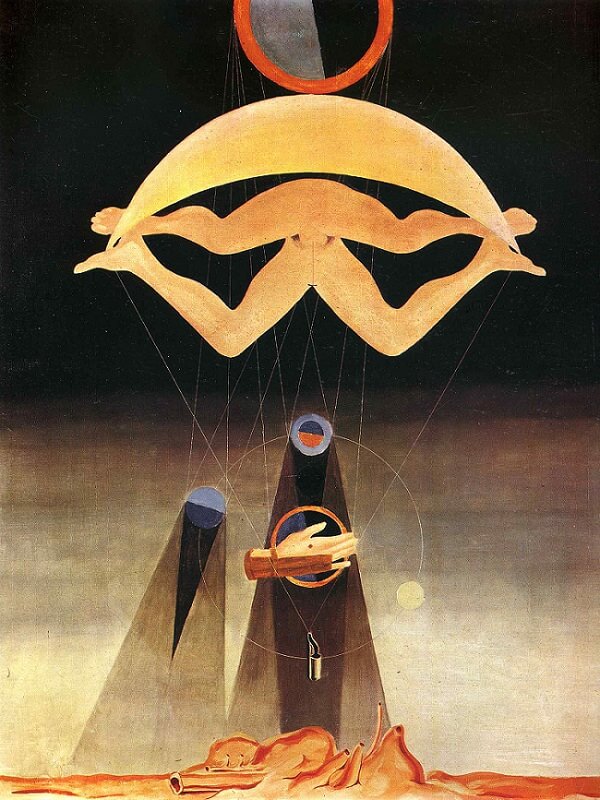

Ernst studied philosophy and psychology in Bonn and was interested in the alternative realities experienced by the insane. This painting may have been inspired by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s study of the delusions of a paranoiac, Daniel Paul Schreber. Freud identified Schreber’s fantasy of becoming a woman as a ‘castration complex’. The central image of two pairs of legs refers to Schreber’s hermaphroditic desires. Ernst’s inscription on the back of the painting reads: ‘The picture is curious because of its symmetry. The two sexes balance one another.’

ALSO: Andrade’s The Structure of the Atom. Arthur Eddington publishes the textbook The Mathematical Theory of Relativity. Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch in Munich fails. Two hundred thousand KKK members attend a conclave in Kokomo, Ind. Messerschmitt establishes his aircraft factory. Coolidge becomes US president. Philosophy of Symbolic Forms (1923–1929), Cassirer’s most important work; whereas animals perceive their world by instincts and direct sensory perception, he argues, humans create a universe of symbolic meanings. Sayers’s Whose Body? (the first Wimsey adventure), Wodehouse’s The Inimitable Jeeves, Christie’s Murder on the Links. Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk. Buber’s I and Thou, Freud’s The Ego and the Id. End of Dada movement.

Einstein’s Sidelights on Relativity, which Rucker describes as “highly readable.” It contains translation of his 1920 address “Ether and the Theory of Relativity” (1920) and “Geometry and Experience” (1921). See 1920 and 1921.

The Hungarian philosopher György Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Makes concepts such as alienation and reification central to Marx’s theory, and argues for the primacy of the concept of totality. The book helped to create Western Marxism and is the work for which Lukács is best known. A crucial text for the French Situationist theorist Guy Debord, and for Theodor W. Adorno’s Critical Theory.

New Lands is the second nonfiction book of the author Charles Fort, published in 1923. It deals primarily with astronomical anomalies.

Fort expands in this book on his theory about the Super-Sargasso Sea – a place where earthly things supposedly materialize in order to rain down on Earth – as well as developing an idea that there are continents above the skies of Earth. As evidence, he cites a number of anomalous phenomena, including strange “mirages” of land masses, groups of people, and animals in the skies. He also continues his attacks on scientific dogma, citing a number of mysterious stars and planets that scientists failed to account for.

Of all of Fort’s books, New Lands is the worst-regarded. His speculations (serious or joking, he does not reveal) concerning continents in the sky and the supposed top-like shape of the Earth have dated considerably.

JBS Haldane’s original lecture on the subject to the Heretics on 4th February 1923 was attended by C. K. Ogden. It was Ogden who urged the publication of Daedalus; it sold 15,000 copies in its first year and was in its seventh impression by 1926. Most likely prefiguring Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), Daedalus is a book of prophecies.

Herbert Read’s poems in The Mutations of the Phoenix (1923) help inaugurate a neo-metaphysical school in modernist poetry (running through Empson, Michael Roberts, c. Day Lewis), which incorporate science into poetry.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin