RADIUM AGE: 1925

By:

October 9, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1925, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: BLASTER (a weapon that fires a destructive beam of energy) | MATTER-TRANSMITTING (designating or relating to a matter transmitter) | ROCKET-SHIP (a spacecraft powered by rockets) | SPACE CRUISER (a spaceship).

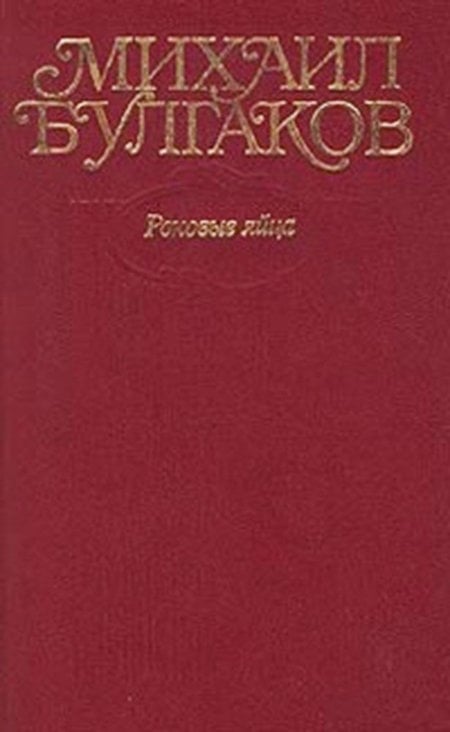

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s satirical science fiction adventure The Fatal Eggs. In a near-future (or perhaps alternate-history) Moscow, the zoologist Vladimir Ipat’evich Persikov discovers a ray that causes frogs and other organisms to mature and reproduce at a rapid rate. At the same time, however, a disease wipes out all of Soviet Russia’s domesticated poultry. Persikov’s equipment is confiscated by the authorities, and thousands of chicken eggs are sent to his laboratory… so that the ray can be used to regenerate the country’s chicken population overnight. Unfortunately, a mixup causes snake and crocodile eggs, instead of chicken eggs, to be treated with the growth ray. Catastrophe! Is the novel a satire — cf. Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita — of the leadership of Soviet Russia? Certainly, some critics at the time suspected as much. However, the novel (novella, really) is squarely in the tradition of western science fiction — from Frankenstein to H.G. Wells’s The Food of the Gods, say — which warns arrogant scientists not to meddle too deeply in nature’s mysteries.

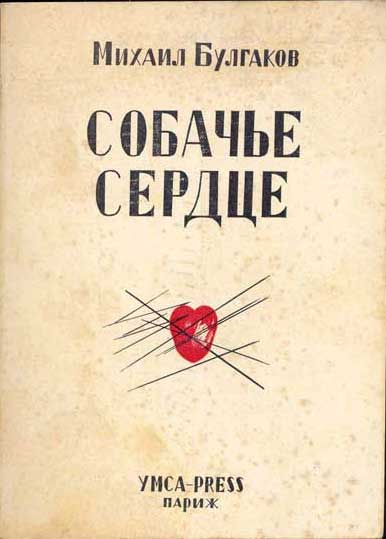

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog (1925). A comedic thriller that mostly takes place inside a Moscow apartment. Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky and his assistant, Dr. Bormenthal, implant the sexual organs and pituitary gland of an evil man into Sharik, a well-behaved dog. The scientists believe that they are imposing a progressive scientific system upon the Russian people; indeed, the resulting creature, a lout who calls himself “Sharikov” — succeeds all too easily in Soviet society. (Is Bulgakov’s story a satire on Communist attempts to create a New Soviet man? No doubt. But it’s also an homage to H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau.) How will Dr. Bormenthal deal with the problematic Sharikov? Firmly. Fun fact: Written in 1925, the book was considered critical of the Soviet state — so until after the fall of the USSR, it circulated in samizdat only.

- Vsevolod Ivanov and Viktor Shklovsky’s Iprit (Mustard Gas). Issued serially in nine parts. A satirical detective/sf novel. Ivanov (1895–1963) and Shklovsky (1893–1984) both had connections to the literary group the Serapion Brothers, who upheld the creed that art must be independent of political ideology. Iprit is a parody of Soviet science fiction, involving a deadly new gas designed for use in a future world war. Ivanov and Shklovsky both later capitulated to the Soviet demands of realistic art. Shklovsky was a Russian and Soviet literary theorist, critic, writer, and pamphleteer. He is one of the major figures associated with Russian formalism. Note that his Theory of Prose came out the same year as this book!

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s The Navigators of Infinity (1925). Astronauts travel to Mars in the Stellarium, a spaceship made of “argine” (an indestructible, transparent material), and powered by artificial gravity. On Mars, the explorers come in contact with two races: the peaceful, six-eyed, three-legged “Tripèdes,” who have ceased to reproduce and are dying out; and the invading “Zoomorphs.” Having fallen in love (!) with one of the human astronauts, a young Martian female — merely by wishing it — gives birth to a child. This joyous event heralds the rebirth — City of Men-style — of the Martian race. Fun fact: Sci-fi scholars claim that Rosny aîné [Joseph Henri Honoré Boex, whose nom de plume contains the word “elder” (aîné) because he and his younger brother used to write together under the joint moniker J.-H. Rosny], author of the seminal 1909 prehistoric-fiction novel Quest for Fire, coined the word “astronautique” in this novel. Rosny aîné, who began writing in the 1880s, is considered the second-most important pioneer in French science fiction, after Jules Verne.

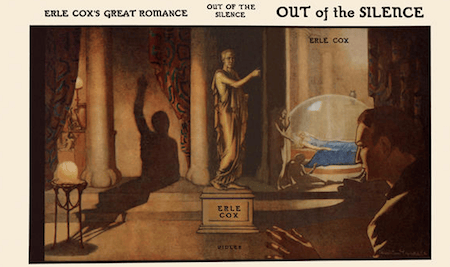

- Erle Cox’s Out of the Silence (1925). Having stumbled upon the subterranean repository of a long-vanished, fantastically advanced civilization, Alan Dundas awakens a beautiful woman from a state of suspended animation. Earani’s amazing intelligence and abilities are the end result of her civilization’s worldwide eugenics program, which she intends to put back into practice, as soon as she conquers the planet. “This world of yours is full of pain and misery… Is any price too great that buys a perfect and wholesome humanity?” Earani demands of Australia’s prime minister. “You hold that to carry out my mission would be a crime. I hold that to fail in doing so would be a crime.” (Alan, who falls in love with Earani, is undisturbed by her plan to wipe out the “colored races” and inferior whites; one is not sure what the author himself thinks about this subject.) David Bowie’s synopsis: “Here she comes, here she comes again/The same old painted lady/From the brow of the superbrain/She’ll scratch this world to pieces/As she comes on like a friend.”

- Lady Dorothy Mills’s The Dark Gods. Probably not SF, set in Africa. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

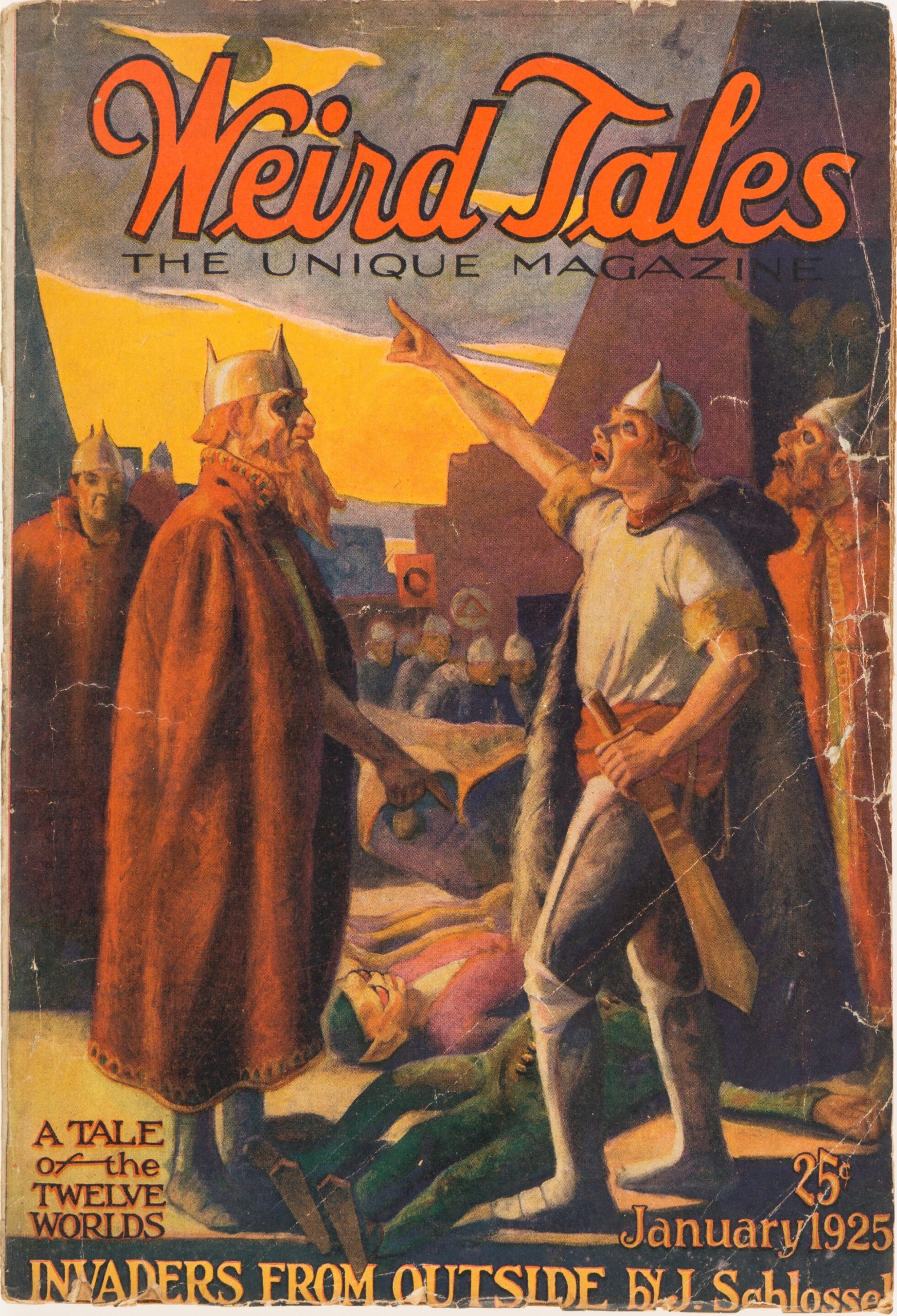

- Lenore Chaney’s “White Man’s Madness” (January 1925) in Weird Tales. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- G.K. Chesterton’s Tales of the Long Bow, tall tales of literalized figures of speech (the Thames, thanks to industrial pollution, is easily set on fire) which culminate in a near-future English revolution.

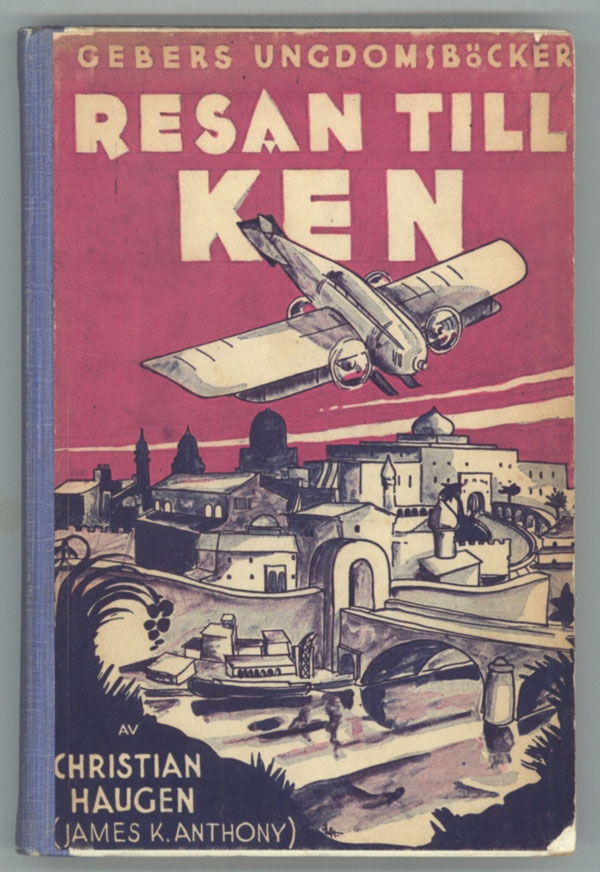

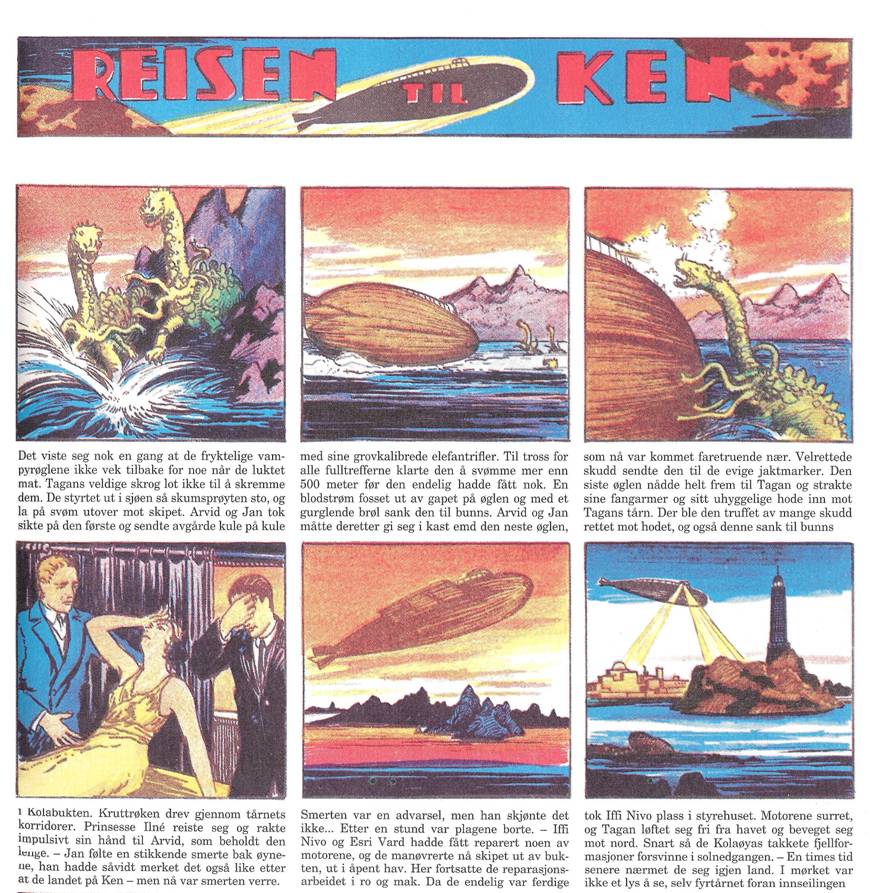

- James K. Anthony (writing as “Christian Haugen”)’s Resan Till Ken. Journey to Ken is a popular sf novel by a Norwegian author. The space cruiser Tagan travels to the planet Ken. The story was adapted into a comic strip (written by Haugen and drawn by Arent Christensen) which ran in the magazine Arbeidermagasinet for Alle in 1933-1934, and was continued by the same team as “Den Tause Verden” in 1935-1936. Journey to Ken is one of the world’s earliest science fiction comic strips.

- Hilaire Belloc’s Mr. Petre. An ironic tale of high finance, politics, and the problems caused by amnesia.

- Maurice Renard and Albert Jean’s Le Singe (curiously translated as Blind Circle, 1928). The author’s most detective-like sf narrative — perhaps patterned on Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” First appeared in feuilleton format (in 62 episodes) in a Parisian pulp journal. Its plot concerns a police investigation of the mysterious presence of multiple dead bodies — all of the same person, a certain Richard Cirugue. After innummerable twists and turns in the narrative, the mystery is finally solved: Richard is actually still alive. Using his recent discovery of an electrolysis procedure to duplicate (but not animate) animal and human tissue, he had fabricated lifeless clones of himself and scattered them around Paris as a publicity stunt to attract investment capital for his scientific research. In an even more bizarre twist, Richard subsequently dies (for real) but his spirit manages to survive and ultimately inhabits the cloned body of his brother, whose wife he lusts after.

- José Moselli’s La Fin d’Illa (20 January-9 July 1925 Sciences et Voyages). Of very considerable sf interest. Translated by Brian Stableford as Illa’s End in 2011. In 1875 a ship discovers a previously unknown island, full of massive artifacts, including many ancient documents dating back to Gondwana, more than a hundred million years earlier. They described the conflict between the Cities of Illa and Nour, describing a civilization extraordinarily advanced in terms of technology – including nuclear weapons, force fields, flying saucers, solar power, and genetically engineered ape-like slaves. Fun fact: Moselli’s science fiction appeared exclusively in popular magazines like L’Épatant, L’Intrépide, Cri-Cri, etc. It was not until 1970 that any of his magazine publications were republished in book form.

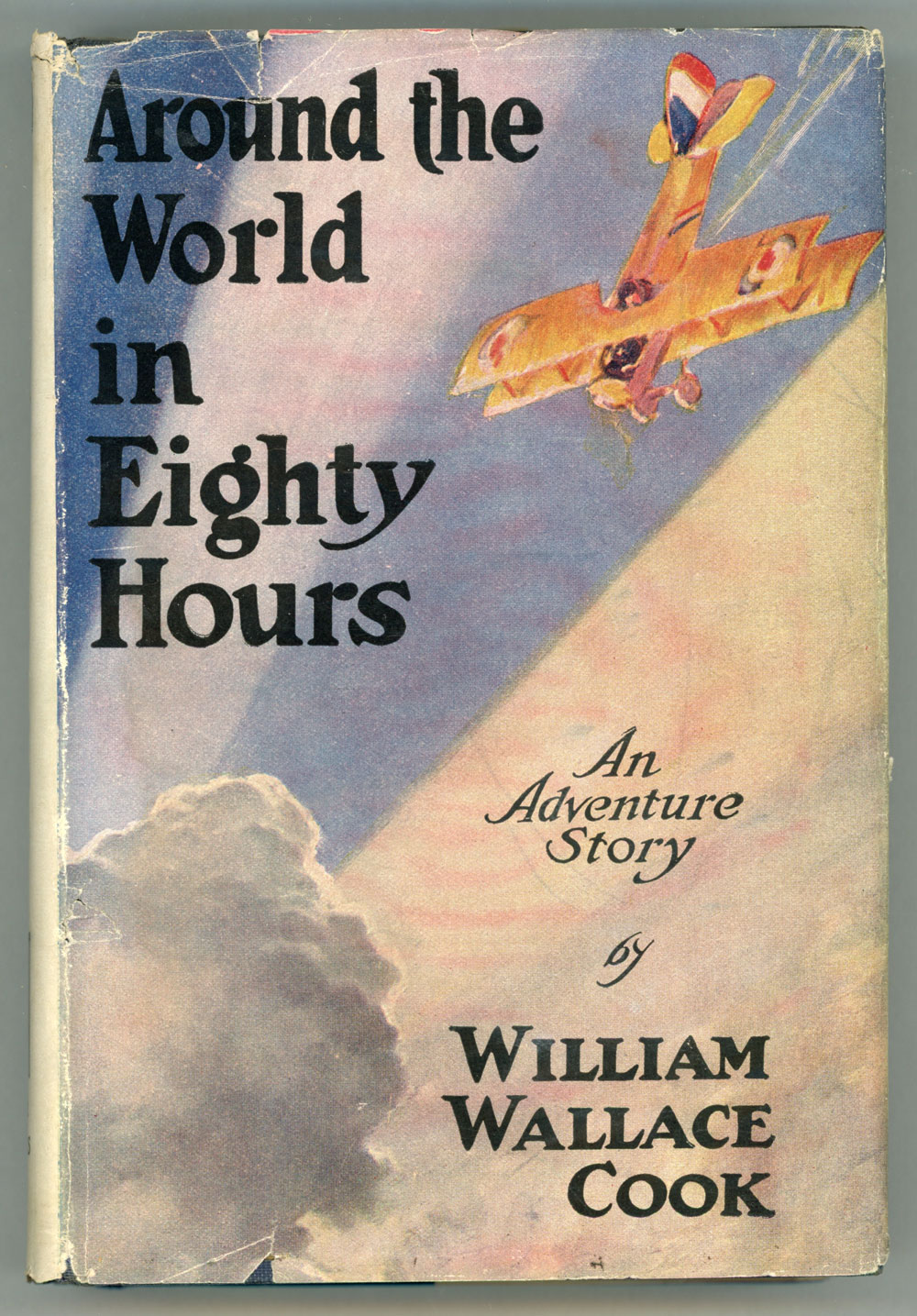

- William Wallace Cook’s Around the World in Eighty Hours. A race around the world in futuristic space-going aircraft.

- Berenice V. Dell’s The Silent Voice. A very long utopian romance set in the fortieth century. “Sex-role reversal in the far future.” – Sargent.

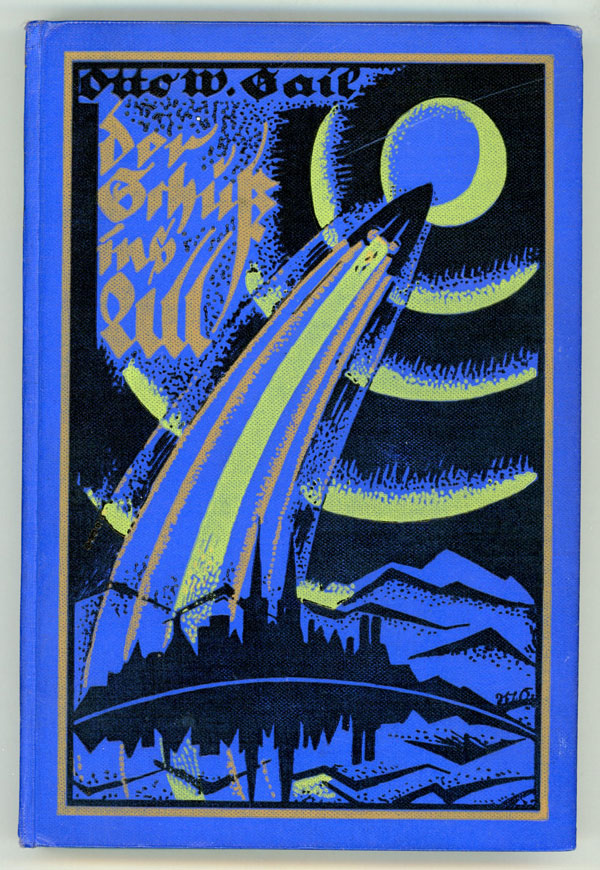

- Otto Willi Gail’s Der Schuss ins All. Gail’s first SF novel, a fictional treatment of mankind’s first step into space. The story was translated into English by Francis Currier and published as “The Shot into Infinity” in Hugo Gernsback’s SCIENCE WONDER QUARTERLY, Fall 1929.

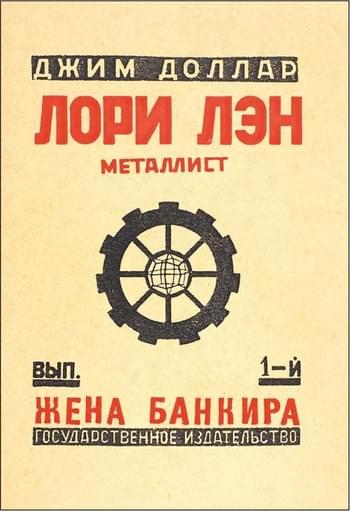

- Marietta Shaginyan’s Лори Лэн, металлист (Lori Len, metallist) [translated as “Laurie Lane, Metalworker”]. Sequel to Mess-Mend: Yankees in Petrograd (see 1924). Wikipedia erroneously gives the date for this one as 1924.

- H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Temple” — appears in the 1980 anthology Science Fiction: The Best of Yesterday.

- Alexander Beliaev’s Golova professora Douela [“Professor Dowell’s Head”] (1925; exp 1938). Melodrama involving a severed head attached to anew body. The most prominent writer of pre-World War Two sf in Russia was Alexander Beliaev, author of more than 60 books. His Chelovek-amfibia (1928; The Amphibian), Golova professora Douela [“Professor Dowell’s Head”] and Ariel (1941) are known to all Soviet schoolchildren, being constantly reprinted. Most of his novels are set in capitalist countries whose social and scientific mores are fiercely criticized. The “Red Detective Story” theme of world revolution virtually disappears in Beliaev, doubtless as a consequence of Trotsky’s disgrace and exile in 1927.

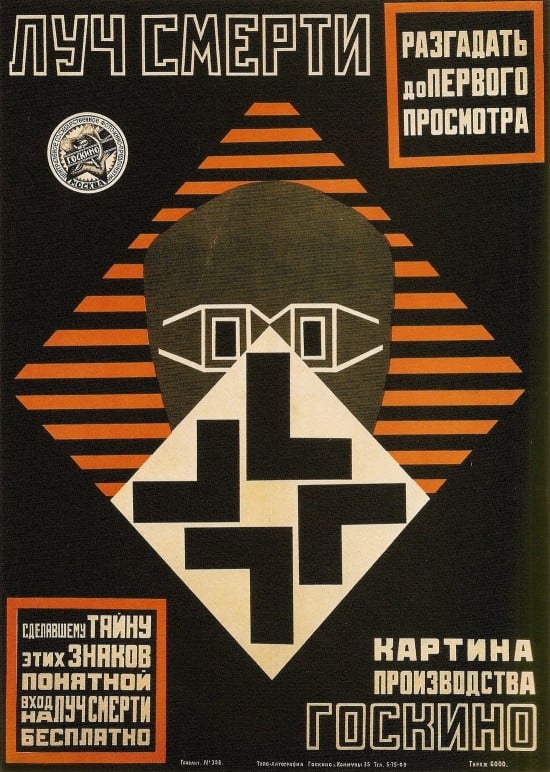

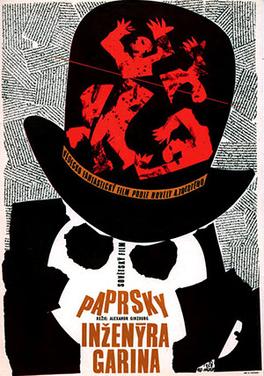

- Alexei Tolstoy’s Giperboloid inzhenera Garin (1925-1926; 1933; rev 1939; trans 1936 as The Death Box; rev edition trans 1955 as The Garin Death Ray). Another good example of the subgenre known as the “krasnyi detektiv” [“Red Detective Story”]: stories of adventures abroad often involving assistance to world revolutionary movements, and often with a fantastic element such as a new weapon. Vladimir Nabokov considered it Tolstoy’s finest fictional work. The Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin is a black-and-white 1965 Soviet science fiction film based on Aleksey Tolstoy’s novel of the same name

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s “The Moon Men” and “The Red Hawk.” Parts of The Moon Men. Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2013.

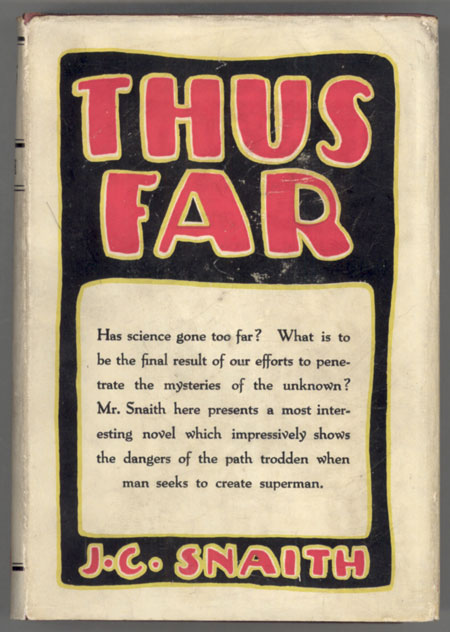

- J.C. Snaith’s Thus Far. “Murder mystery against a background of biological experimentation… The book must have impressed Stanley G. Weinbaum, two of whose stories seem strongly indebted to it.” – Bleiler.

- G.K. Chesterton’s Tales of the Long Bow. Collection of linked stories. Tall tales of literalized figures of speech which culminate in a near-future English revolution.

- Gilbert Collins’s The Starkenden Quest (1925). An underground civilization is located somewhere north of Khmer, whose primordial dwarf inhabitants (they are not throwbacks, as wvolution seems to have passed them by) are enthralled by an immortal blonde priestess. A great flood ends the tale.

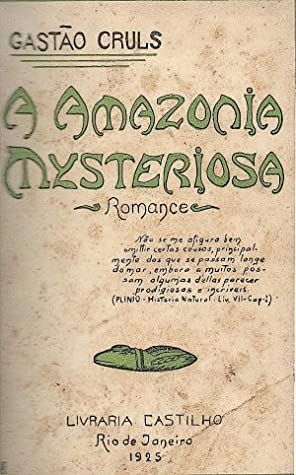

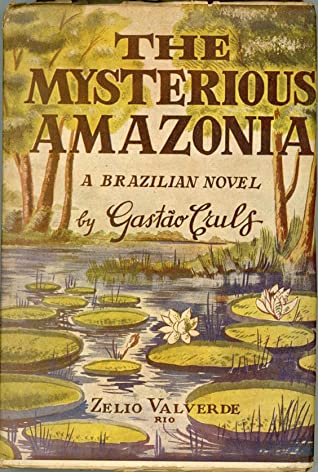

- Gastão Cruls’s A Amazônia misteriosa (1925; trans J T W Sadler as The Mysterious Amazonia. An adventure novel featuring a tribe of warrior women (descended from the Incas) and a German scientist who performs Moreau-like experiments on Indians.

- Greye La Spina’s “Invaders from the Dark.”

- Greye La Spina’s “The Remorse of Professor Panebianco.” In which a mad scientist sacrifices the woman who loves him for his ambition in a lethal experiment. Think Shelley’s Frankenstein in reverse: instead of discovering the secret to bringing the dead back to life only to abandon it, the horror is derived from the sacrifice of love in service of power.

- Greye La Spina’s “The Last Cigarette.”

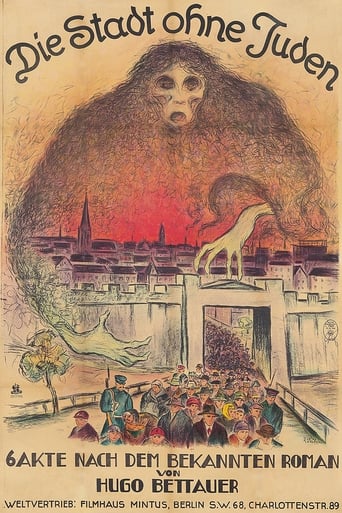

- Hugo Bettauer’s Die Stadt ohne Juden [“The City without Jews”]. The expelled Jews are finally recalled to restore the prosperity of the city. By a Jewish author.

- Ivan Narodny’s The Skygirl, A Mimodrama.

- Hemendrakumar Roy’s Meghduter Marte Agaman (The Arrival of the Messengers from the Skies, 1925-26). A Martian adventure. More info on this Bangla-language novel to come.

- J. Schlossel’s “Invaders from Outside” (Weird Tales). Schlossel was a pioneer contributor of space opera to the pulp magazines, ahead of Edmond Hamilton and E E Smith. He published just six stories. His first, “Invaders from Outside,” is set aeons hence in the solar system’s past when Earth carried only primitive life but where intelligent life exists on Earth’s Moon, Mars several of the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn plus a fifth planet between Mars and Jupiter which at the end of the story is destroyed and forms the asteroid belt. This life forms a confederation which is benign but which has to do battle with a violent parasitic alien planet that enters the solar system. Ashley says Schlossel is ignored today although his work in the twenties showed considerable originality.

- Karel Čapek’s The Makropoulos Secret (performed 1922: 1922; unauthorized trans by Randal C Burrell in novel format as The Makropoulos Secret 1925; authorized trans by Paul Selver of rev text vt The Macropoulos Secret 1927). Cloaks in comic routines the terrifying story of the alluring, world-weary, 300-year-old protagonist, the secret of her longevity, and her ambivalently conceived death. The work is most familiar as the basis of a 1926 opera by Leoš Janáček.

- Berenice V. Dell’s The Silent Voice. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- V. Torlesse Murray’s The Rule of the Beasts. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Maurice Baring’s Half a Minute’s Silence. Collects twenty-five stories including the author’s outstanding horror story “Venus.”

- Nictzin Dyalhis’s “When the Green Star Waned” (Weird Tales). An early space opera — badly written.

- Salvador de Madriaga’s The Sacred Giraffe. Political satire in which black women don’t believe white people existed or that men ever ruled.

ALSO: Heisenberg, Bohr, and Jordan develop quantum mechanics for atoms. Millikan discovers cosmic rays in the upper atmosphere. Cecilia Payne’s PhD thesis provides spectral evidence that stars are composed almost entirely of hydrogen with helium, contrary to scientific consensus at the time. Burtt’s The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science is published. Baird successfully transmits the first television pictures. Scopes goes on trial for violating Tennessee law that prohibits the teaching of evolution. Hitler reorganizes Nazi Party and publishes Mein Kampf. Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Kafka’s The Trial (posthumously), Stein’s The Making of Americans. The New Yorker begins to appear. Chaplin’s The Gold Rush, Lloyd’s The Freshman. The Charleston becomes a fashionable dance; crossword puzzles come into vogue.

In 1925, a New York Times article ran the headline, “New Radium Disease Found; Has Killed 5.” The new disease was called, “radium necrosis,” a polite term for the painful process of one’s jaw disintegrating and developing tumors. The five killed by this so-called “new radium disease” were a handful of the girls who were instructed to put radium in their mouths by way of paintbrush. “Trust in radium unjustified,” the article sources from a New York doctor. “Cancer called incurable.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin