Best 19th c. Adventure

By:

September 9, 2013

This series of nine posts, the first of which you are reading now, will list what I consider to be the Top 32 adventure novels from the 19th Century, as well as the Top 21 adventure novels from each of the first eight socio-cultural decades — the Oughts (1904–1913), the Teens (1914–1923), the Twenties (1924–1933), the Thirties (1934–1943), the Forties (1944–1953), the Fifties (1954–1963), the Sixties (1964–1973), and the Seventies (1974–1983) — of the 20th Century.

Which adds up to a Top 200 list of my all-time favorites.

There’s more! In this post (on 19th Century adventures), I’ve appended a list of 18 second-tier favorites — for a grand total of 50 Top Adventures of the 19th Century. And in subsequent posts, I’ve also appended a list of 29 second-tier favorites — for a grand total of 50 Top Adventures of each 20th Century socio-cultural decade. All in all, then, I’ve listed 450 Top Adventures from 1805–1983. And there’s more! Each post also includes a third tier of adventures worth a mention.

A note about these third-tier lists of adventures: I hope HiLobrow readers will peruse them closely, because (unlike the titles on my Top 32 or 21 lists, and unlike most of the titles on my 2nd-tier favorite lists) they tend to have fallen into obscurity. Many are no longer in print; most haven’t been digitized yet. These are terrific adventures! If they weren’t, I wouldn’t have included them. Instead of thinking of them as “third-rate,” please think of the titles on my third-tier adventure lists as Most Deserving of Rediscovery.

This series of nine posts is just a starting place. My intent is to put these lists out there for discussion and criticism; I will make changes to them after posting — certainly to the 2nd- and 3rd-tier lists of favorite adventures, but perhaps even to the 1st-tier lists. Down the road, I’ll draw upon these lists to create genre-specific lists of favorite adventures. I’ll also draw upon these lists — particularly the 3rd-tier lists — for inspiration in my publishing project(s).

I also intend to create another series of adventure novel lists — perhaps 20 altogether — in which I’ll name my favorite adventure novels by theme. For example: stranded on a desert island, roaming the frontiers of civilization, living by your wits, treasure hunt, unlikely companions united for a common purpose, secret identity, cat-and-mouse game, escaping from prison, cracking a code, a test of one’s loyalty or honor or courage, a conspiracy plot, a revenge scheme, battling the elements, civilized people reverting to savagery. Soon!

I hope you enjoy the list below (fellow James Fenimore Cooper haters — please note the caveat included in the writeup of The Last of the Mohicans, and note that except for his little-known The Crater, there aren’t any other Cooper titles in the Top 50), and the series. Please leave comments! My thanks to io9.com readers who have done so already; I’ve followed your excellent advice.

If you’re interested in reading re-discovered science fiction adventures, check out the 10 titles from HiLoBooks — available online and in gorgeous paperback form.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Index to All Adventure Lists | Introduction to Adventure Themes & Memes Series | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade

In chronological order:

- * 1814. Walter Scott’s 18th c. frontier adventure Waverley. The novel — which sends a young Englishman adventuring in the highlands of Scotland, during the Jacobite uprising which sought to put Bonnie Prince Charlie on the British throne — is regarded as the first historical novel. Note that Scotland, that savage tribal land just across the border from hyper-civilized England, was the original adventure frontier.

- * 1818. Mary Shelley’s Gothic science fiction adventure Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. From multiple points of view, we read about a brilliant scientist and his creation: a dehumanized creature who longs for love and friendship and, eventually, revenge. PS: There are two editions of the book; the 1831 “popular” edition was heavily revised and tends to be the one most widely read; scholars tend to prefer the 1818.

- * 1820. Walter Scott’s 12th c. knightly adventure Ivanhoe, the protagonist of which makes his first appearance at a tourney in disguise, known only as The Disinherited Knight. (Also at that tourney is a mysterious archer named Locksley. Who can it be?) This popular book was single-handedly responsible for the medievalist craze in early 19th-century England.

- 1826. James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier adventure The Last of the Mohicans. Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales were popular and influential (esp. in France!), and therefore deserve a mention here — despite the fact that Mark Twain tore Cooper a new one. Despite its flaws — there are many! — this novel does feature a truly epic pursuit, so it deserves a place on the Top 21.

- 1837–39. I realize that mentioning a Charles Dickens joint here opens up a can of worms, but Oliver Twist in particular is a great adventure, and the Artful Dodger is awesome.

- * 1838. Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic sea adventure The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Poe’s only complete novel — about a teenager who stows away on a ship, is kidnapped by mutineers and pirates, encounters cannibals, and explores the Antarctic before discovering the key to all Western mystical traditions — has been described as “at once a mock nonfictional exploration narrative, adventure saga, bildungsroman, hoax, largely plagiarized travelogue, and spiritual allegory.”

- * 1844. Alexandre Dumas’s 17th c. swashbuckling adventure The Three Musketeers introduces us to three unforgettable characters: the distinguished, highly educated Musketeer Athos; the religious and scholarly yet womanizing younger Musketeer Aramis; and the Falstaffian Musketeer Porthos. It is their sanguine companion D’Artagnan who coins the classic phrase “All for one, and one for all!”

- 1844–45. Alexandre Dumas’s avenger-type adventure The Count of Monte Cristo. It’s all here: a wronged man seeking revenge, a jailbreak, poisonings, smugglers, a sex slave (spoiler: she’s freed), and a treasure cave. Serialized in 117 installments, it’s on the long side; still, according to Luc Sante, this story is today as “immediately identifiable as Mickey Mouse, Noah’s flood, and the story of Little Red Riding Hood.”

- 1847. James Fenimore Cooper’s sea-going adventure The Crater. Fun fact: Adventure aficionados consider this one much superior to his Leatherstocking tales!

- * 1851. Herman Melville’s sea-going adventure Moby-Dick is, we all know, much more than it appears to be on the surface. It is an allegory of (maybe) man’s gnostic rage against the occluded world in which he lives, separated from real reality. Perhaps more than you want to know about how whaling works, but one of the all-time great yarns.

- 1865. Lewis Carroll’s fantasy adventure Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

- 1868. Wilkie Collins’s detective adventure The Moonstone. Generally considered the first English-language detective novel.

- * 1870. Jules Verne’s science-fiction adventure Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea introduces us to Captain Nemo, a scientific genius who roams the depths of the sea in his submarine — in quest of treasure, knowledge, and revenge. NB: The book inspired Arthur Rimbaud’s poem “Le Beateau Ivre.”

- 1874. Jules Verne’s science-fiction Robinsonade The Mysterious Island. An engineer, a sailor, a young boy, a journalist, and an African American butler escape a Civil War prison in a hot air balloon and crash land on a Lost-type island in the South Pacific. Who is observing them, helping them? Marred by didactic lessons of all sorts.

- * 1876. Jules Verne’s espionage adventure Michael Strogoff, considered one of Verne’s best books. When the Tartar Khan incites a rebellion and separates the Russian Far East from the mainland, Michael Strogoff, courier for Tsar Alexander II, is sent to Irkutsk on a crucial mission.

- * 1883. Robert Louis Stevenson’s 18th c. treasure-hunt adventure Treasure Island, which led to the popular perception of pirates as we know them today: e.g., peg-legged, one-eyed. Note that the castaway character Ben Gunn is a parody of Daniel Defoe’s character Robinson Crusoe!

- 1884–45. Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn — note that Twain, who scorned Walter Scott-type romances, uses the term “adventure” sardonically. He was poking holes in the prevailing sentimental and Romantic ethos of the literary establishment. Still, Twain’s novel is a fun romp through the American South in its grotesquerie, and it offers authentic thrills along the way.

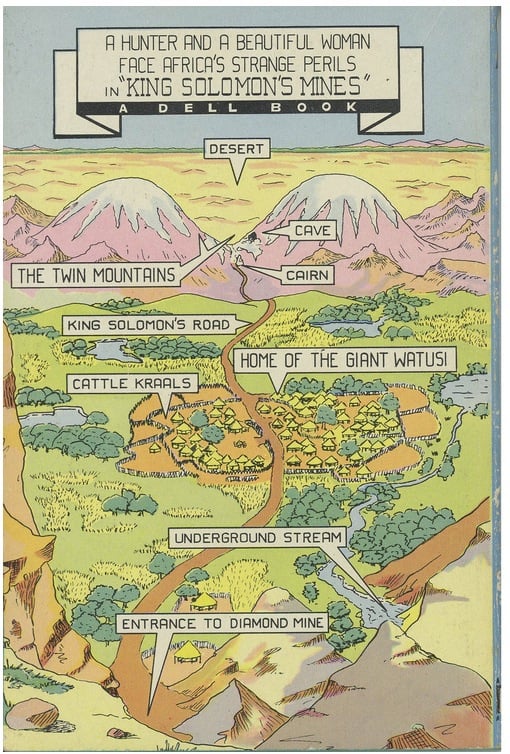

- * 1885. H. Rider Haggard’s frontier adventure King Solomon’s Mines, which set a new standard for thrills — thanks to the author’s illiberal belief that denizens of England are so coddled that they’ve forgotten their own savage nature. The first novel written in English that was based on the African continent, and the first “Lost World” adventure. NB: Haggard would write 18 books featuring Allan Quatermain, the hero of King Solomon’s Mines.

- * 1886. Robert Louis Stevenson’s 18th c. avenger-type adventure Kidnapped, in which young David Balfour is sold into servitude by his wicked uncle. With the help of Alan Breck, a daring Jacobite, David escapes and travels across Scotland by night — hiding from government soldiers by day.

- 1887. H. Rider Haggard’s treasure hunt/occult adventure She. Weird fun, particularly if you like reincarnation stuff. Spoiler: In a later novel, She and Quatermain will cross paths!

- * 1888. Rudyard Kipling’s Haggard-esque frontier adventure The Man Who Would Be King. Two British adventurers become kings of a remote part of Afghanistan, because — it turns out — the Kafirs there practice a form of Masonic ritual and the adventurers know Masonic secrets.

- * 1891. Arthur Conan Doyle’s knightly adventure The White Company. Perhaps more of an ironic homage to than a sardonic inversion of the genre. Actually one of his best adventures!

- 1891. H. Rider Haggard’s Viking adventure Eric Brighteyes. Considered one of his best books.

- * 1894. Anthony Hope’s swashbuckling adventure The Prisoner of Zenda, which takes place in the fictional central European country of Ruritania, and which concerns a political decoy restoring the rightful king to the throne, was so influential that its genre is now called Ruritanian. Perhaps the first political thriller.

- * 1896. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The Island of Doctor Moreau. Edward Prendick, a shipwrecked man, is left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, who creates human-like beings from animals. After Moreau is killed, the Beast Folk begin to revert to their original animal instincts.

- * 1897. Bram Stoker’s supernatural horror adventure Dracula, whose readers know what kind of monster the protagonists seek before they do. Described by Neil Gaiman as a “Victorian high-tech thriller,” the book’s use of cutting-edge technology — and true-crime story telling, from newspaper clippings to phonograph-recorded notes — creates an eerily realistic vibe.

- 1898. Alfred Jarry’s ’pataphysical adventure Gestes et Opinions du Docteur Faustroll, Pataphysicien. Faustroll and his monkey butler travel around Paris — on a mythical register — in a high-tech boat/vehicle. Published posthumously, in 1911.

- 1899. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the protagonist of which is sent up a river in Africa to seek the European manager of a remote ivory station who has turned into a charismatic monster, is a sardonic inversion of yarns by adventure authors who didn’t give much thought to the colonialist and racist context within which their civilization-vs.-savagery narratives played out. “The horror! The horror!”

- * 1900–01. Rudyard Kipling’s espionage adventure Kim, in which an Irish orphan in India not only becomes the disciple of a Tibetan lama, but is recruited by the British secret service to spy on Russian agents participating in the Great Game. In the process, he races across India; Kipling — an imperialist, but a keen observer of India all the same — brilliantly captures the essence of that country under the British Raj.

- * 1901. Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective mystery adventure The Hound of the Baskervilles. Mystery adventures don’t have a large place on these lists of mine… because although they’re fun exercises in ratiocination and puzzle-solving, they’re often not particularly thrilling. Conan Doyle, however, is a great adventure writer. And this novel is not your typical Sherlock Holmes story; it is jam-packed with thrills and chills.

- * 1903. Robert Erskine Childers’s espionage adventure The Riddle of the Sands can be a demanding read for those with no interest in sailing or timetables. But it’s a thrilling yarn nevertheless, one which sought to alert British readers to the danger of German invasion. Its protagonists are archetypes of the amateur adventure hero, the likes of whom would later appear so memorably in the novels of John Buchan.

- * 1903. Jack London’s Klondike adventure The Call of the Wild, which expresses the author’s notion that because the veneer of civilization is fragile, humans revert to a state of primitivism with ease. PS: Note that London’s White Fang shows the flipside of this trajectory.

ALSO SEE: The Best Scientific Romances (1864–1903)

ALSO SEE: The Best Scientific Romances (1864–1903)

ALSO SEE: The Best Scientific Romances (1864–1903)

ALSO SEE: The Best Scientific Romances (1864–1903)

PS: According to my eccentric periodization scheme, about which I’ve written elsewhere, the first year of the 19th Century is 1805, and its final year is 1903.

PPS: The starred entries on the list are those titles I would include on a shorter list of the Top 21 19th-Century Adventures.

- 1817. Walter Scott’s Waverly adventure Rob Roy, in which a young Englishman travels to the Scottish Highlands in order to collect a debt stolen from his father. During his travels he encounters Rob Roy MacGregor — the folk hero and outlaw known as the Scottish Robin Hood.

- 1860. Paul Féval’s vampire adventure Knightshade (French: Le Chevalier Ténèbre).

- 1867. Ouida’s frontier adventure Under Two Flags takes place in North Africa. With a twist: The hero feels morally and emotionally on the side of those he fights against.

- 1868. Jules Verne’s exploration adventure Around the World in Eighty Days.

- 1868. Émile Gaboriau’s crime adventure Monsieur Lecoq. The first case of the titular policeman (an ex-criminal), who’d made sporadic appearances in earlier works by the author, and who was to prove a major influence on Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes.

- 1871. Lewis Carroll’s fantasy adventure Through the Looking-Glass. Enter the Jabberwocky!

- 1876. Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer, which — like Huckleberry Finn — is simultaneously a sardonic inversion of Scott-type romantic adventures, and itself an exciting adventure. The Injun Joe scene in the cave… brrr!

- 1885. Jules Verne’s espionage adventure Mathias Sandorf features: islands, cryptograms, surprise revelations of identity, technically advanced hardware, a solitary figure bent on revenge, a pursuer who is himself pursued, and more. It’s the complete espionage adventure package.

- 1889. William Morris’s fantasy adventure The House of the Wolfings. An important influence on J.R.R. Tolkien.

- 1889. William Morris’s fantasy adventure The Story of the Glittering Plain.

- 1892. H. Rider Haggard’s Zulu adventure Nada the Lily. Considered one of his best books.

- 1894. S.R. Crockett’s The Raiders. Caught up in the strife between smugglers on the Solway Coast and the gypsies of Galloway, young Patrick Heron is flung into a society of outcasts and outlaws.

- 1894. H. Rider Haggard’s lost-race fantasy adventure The People of the Mist.

- 1895. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The Time Machine.

- 1897. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The Invisible Man. A scientist invents a way to change a body’s “refractive index” so that it absorbs and reflects no light. Experimenting upon himself, he becomes invisible… and plans a reign of terror. A great hunted-man type thriller: How do you catch an invisible man?

- 1898. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The War of the Worlds.

- 1900. L. Frank Baum’s fantasy adventure The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

- 1901. M.P. Shiel’s science fiction adventure The Purple Cloud.

- 1808. Heinrich von Kleist’s novella The Marquise of O features some adventure elements.

- 1808. Heinrich von Kleist’s play Penthesilea, about the Amazonian queen, Penthesilea. An exploration of sexual frenzy.

- 1810. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Gothic novel Zastrozzi (1810). An outlaw is obsessed with revenge against men who — it is eventually revealed — are his father and half-brother.

- 1811. Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s fantasy novella Undine.

- 1812. Johann David Wyss’s Robinsonade The Swiss Family Robinson. Marred by moralizing, but (a) sustainable living is modeled, and (b) pirate attack!

- 1815. Walter Scott’s poem The Lady of the Lake.

- 1815. E.T.A. Hoffman’s fantasy adventure The Devil’s Elixirs.

- 1815. Walter Scott’s Waverly adventure Guy Mannering.

- 1819–21. E.T.A. Hoffman’s fantasy adventure The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr.

- 1820. Charles Maturin’s Gothic adventure Melmoth the Wanderer was a favorite of Charles Baudelaire’s and Oscar Wilde’s.

- 1821. James Fenimore Cooper’s espionage adventure The Spy. Set in America during the Revolution. Notable because most readers at the time were not interested in American literature with an American setting.

- 1821. Walter Scott’s Waverly adventure Kenilworth.

- 1821. Charles Nodier’s dream adventure Smarra, ou les démons de la nuit, conte fantastique.

- 1815. Walter Scott’s Waverly adventure The Pirate.

- 1823. James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier adventure The Pioneers. Ace frontiersman Natty Bumppo first appears in this novel. One of the Leatherstocking series.

- 1826. Mary Shelley’s apocalyptic science fiction adventure The Last Man.

- 1827. Alessandro Manzoni’s historical adventure The Betrothed.

- 1831. Victor Hugo’s Gothic-type adventure The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

- 1834–35. Honoré de Balzac’s avenger-type adventure Le Père Goriot. The notorious Vautrin may have helped inspire Émile Gaboriau’s character Monsieur Lecoq.

- 1835. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “Young Goodman Brown” deserves a mention because it’s the same plot as Edgar Wright’s 2007 movie Hot Fuzz.

- 1840. James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier adventure The Prairie. One of the Leatherstocking series.

- 1840. James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier adventure The Pathfinder. One of the Leatherstocking series. If you were going to read one of this series besides Last of the Mohicans, this is the one.

- 1841. James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier adventure The Deerslayer. One of the Leatherstocking series.

- 1843. Edgar Allan Poe’s hermeneutic adventure “The Gold-Bug.” A terrific tale of ratiocination which I’d include on the Top 21 list… except it isn’t a novel.

- 1843. Paul Féval’s swashbuckling adventure Le Loup Blanc.

- 1845. Alexandre Dumas’s Three Musketeers sequel Twenty Years After.

- 1846–47. James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest’s penny-dreadful adventure The String of Pearls. The literary debut of Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

- 1846. Herman Melville’s sea-going adventure Typee, in which a whaleman who jumps ship is confined by a cannibalistic tribe, was praised by Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and other contemporaries.

- 1847–50. Alexandre Dumas’s Three Musketeers sequel The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later. Includes “The Man in the Iron Mask.”

- 1852. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s hunted-man adventure Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

- 1854. Gérard de Nerval’s dream adventure Aurelia.

- 1854. Alexandre Dumas’s crime adventure Les Mohicans de Paris. Monsieur Jackal, the mysterious head of the Paris Sûreté, may have helped inspire Émile Gaboriau’s character Monsieur Lecoq.

- 1857. Paul Féval’s swashbuckling adventure The Hunchback (French: Le Bossu).

- 1860. Wilkie Collin’s thriller The Woman in White wasn’t the first “novel of sensation,” but it popularized the genre for a mass audience. Fun fact: the story was published in Charles Dickens’s magazine All the Year Round.

- 1862. Victor Hugo’s Gothic avenger-type adventure Les Misérables. Jean Valjean, a.k.a. Monsieur Madeleine, Ultime Fauchelevent, Monsieur Leblanc, and Urbain Fabre, struggles to lead a normal life — under various aliases — after serving a 19-year prison sentence for stealing bread for his starving sister and her family. Not really an adventure, but it has adventurous moments.

- 1874. Paul Féval’s vampire adventure La Ville Vampire.

- 1864. Jules Verne’s exploration adventure Journey to the Center of the Earth is pretty fun, though near-fatally marred, IMHO, by the didactic geography lessons. PS: Scholars claim that J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit was heavily influenced by this novel.

- 1864. Sheridan Le Fanu’s fantasy thriller Uncle Silas. Not exactly an adventure.

- 1865. Paul Féval’s vampire adventure La Vampire.

- 1866. Charles Kingsley’s knightly adventure Hereward the Wake tells the story of the last Anglo-Saxon holdout against the Norman Conquest. Troubling admiration for Teutonic vigor… but a ripping yarn that was instrumental in elevating the real-life Hereward into an English folk-hero.

- 1871. Col. George Tomkyns Chesney’s science fiction adventure The Battle of Dorking. England is invaded by Germany!

- 1871. Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s science fiction adventure Vril, the Power of the Coming Race. Some theosophists, notably Helena Blavatsky, William Scott-Elliot, and Rudolf Steiner, accepted the book as truth!

- 1874. Paul Féval’s vampire adventure La Ville Vampire.

- 1878. Fortune du Boisgobey’s Monsieur Lecoq crime adventure Le Vieillesse de Monsieur Lecoq. Note that the titular character was invented by Émile Gaboriau.

- 1881. Mark Twain’s 16th c. avenger-type adventure The Prince and the Pauper, the humorist’s first attempt at historical fiction. Two young boys — Tom Canty, a pauper who lives with his abusive father, and Prince Edward, son of King Henry VIII — are identical in appearance.

- 1884. Richard Jefferies’s science fiction adventure After London imagines a London reclaimed by nature after some unexplained catastrophe.

- 1885. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Prince Otto: A Romance is set in the imaginary Germanic state of Grünewald. That is, it’s a Ruritanian-type adventure avant la lettre.

- 1886. Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. A terrific psychological thriller. Very short — written in three days.

- 1886. William Busnach and Henri Chabrillat’s Monsieur Lecoq crime adventure La Fille de Monsieur Lecoq. Note that the titular character was invented by Émile Gaboriau.

- 1887. Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective mystery A Study in Scarlet introduces readers to brilliant detective Sherlock Holmes and his companion Dr. Watson.

- 1887. H. Rider Haggard’s frontier adventure Allan Quatermaine is one of many featuring Quatermaine, an English-born professional big game hunter who finds English cities and climate unbearable. We also meet, for the first time, Haggard’s influential Zulu warrior character, Umslopogaas.

- 1887. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes adventure The Sign of Four.

- 1888. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Scott-esque knightly adventure The Black Arrow: A Tale of the Two Roses.

- 1888. Edward Bellamy’s science fiction adventure Looking Backward. A utopian vision more than an adventure; immensely influential and popular in its day.

- 1889. Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court is a sardonic inversion of Scott-esque medieval romances. But — as you might expect — still a fun story.

- 1889. Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Master of Ballantrae. A tale of revenge set in Scotland, America, and India. I haven’t read it — does it deserve to be in my Top 50?

- 1889. Arthur Conan Doyle’s occult adventure The Mystery of Cloomber.

- 1891. Edwin Lester Arnold’s mystical science fiction adventure Phra the Phoenician.

- 1892. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story collection The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

- 1892. Arthur Conan Doyle’s historical adventure The Great Shadow.

- 1893. Arthur Conan Doyle’s historical adventure The Refugees.

- 1893. Robert Louis Stevenson’s frontier adventure Catriona. An excellent sequel to Kidnapped.

- 1894. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story collection The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes.

- 1894. William Morris’s fantasy adventure The Wood Beyond the World.

- 1894. Rudyard Kipling’s collection of stories The Jungle Book. Here the different species of animals seem to represent different tribes or nations in hierarchical order. Not a novel, or I might include it on the Top 21 list. Followed by The Second Jungle Book (1895).

- 1895. Stephen Crane’s military adventure The Red Badge of Courage. Overcome with shame after he flees from a Civil War battlefield, Private Henry Fleming longs for a wound — a “red badge of courage.”

- 1896. Arthur Conan Doyle’s historical adventure Rodney Stone.

- 1896. John Buchan’s knightly adventure Sir Quixote of the Moors. His first novel, written when he was 19. Set in Scotland in the late 17th century.

- 1896. William Morris’s fantasy adventure The Well at the World’s End.

- 1896. Anthony Hope’s collection of Ruritanian adventure/romance stories The Heart of Princess Osra. A prequel of sorts to The Prisoner of Zenda.

- 1896. Arthur Conan Doyle’s story collection The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard is an ironic homage to the picaresque adventure genre. It’s very funny, in a dry British way. But at the same time the action is non-stop, and the protagonist is one of the greatest adventurers ever.

- 1897. Rudyard Kipling’s sea-going adventure Captains Courageous. A spoiled rich teenager is saved from drowning by a fishing boat in the north Atlantic. I love the movie.

- 1897. Arthur Conan Doyle’s historical adventure Uncle Bernac.

- 1897. Stephen Crane’s short story “The Open Boat” — collected in the definitive 1945 collection The Pocket Book of Adventure Stories, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern.

- 1898. Anthony Hope’s Ruritanian adventure Rupert of Hentzau. A sequel to The Prisoner of Zenda. Wildly popular in its day.

- 1898. Alfred Ollivant’s YA canine adventure Bob, Son of Battle. A tremendous adventure set in the English county of Cumbria.

- 1899. John Buchan’s Lost Race adventure story “No-Man’s Land.” The narrator is a young Oxford Fellow in Celtic Studies who during a fishing and walking holiday stumbles on a small tribe of Picts. They have survived for millennia in Galloway cave.

- 1900. Morley Roberts’s frontier adventure The Fugitives. I picked this one up in a thrift store; it is forgotten utterly by contemporary readers. Possibly a YA novel? Anyway, a very exciting South African hunted-man plot.

- 1901. Edwin Lester Arnold’s mystical science fiction adventure Lepidus the Centurion.

- 1901. George Barr McCutcheon’s Ruritanian adventure novel Graustark: The Story of a Love Behind a Throne. Graustark is a fictional country in Eastern Europe; The Prisoner of Zenda is an obvious influence. This book and its sequels were enormously popular. I’m a fan.

- 1902. Owen Wister’s Western adventure The Virginian. Set on a Wyoming cattle ranch, this is the first Western. It’s also a Walter Scott-style knightly romance.

NOTES ON ADVENTURE WRITER GENERATIONS

Original Romantic Generation (1765-74)

1771: Walter Scott (Top 200: Waverley, Ivanhoe)

Original Promethean Generation (1785-94)

1789: James Fenimore Cooper (Top 200: The Last of the Mohicans, The Crater)

Monomaniac Generation (1795–1804)

1797: Mary Shelley (Top 200: Frankenstein)

1802: Alexandre Dumas (Top 200: The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo)

Autotelic Generation (1805–14)

1809: Edgar Allan Poe (Top 200: The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket). HiLo Hero.

1812: Charles Dickens (Top 200: Oliver Twist) HiLo Hero.

Retrogressivist Generation (1815–24)

1819: Herman Melville (Top 200: Moby-Dick). HiLo Hero.

1824: Wilkie Collins (Top 200: The Moonstone). HiLo Hero. Cusper.

Post-Romantic Generation (1825–33)

1828: Jules Verne (Top 200: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, The Mysterious Island, Michael Strogoff). HiLo Hero.

1832: Lewis Carroll (Top 200: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.). HiLo Hero.

Original Decadent Generation (1834–43)

1835: Mark Twain (Top 200: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn). HiLo Hero.

New Promethean Generation (1844–53)

1847: Bram Stoker (Top 200: Dracula). HiLo Hero.

1850: Robert Louis Stevenson (Top 200: Treasure Island, Kidnapped). HiLo Hero.

Plutonian Generation (1854-63)

1856: H. Rider Haggard (Top 200: King Solomon’s Mines, She, Eric Brighteyes, Marie, When the World Shook). HiLo Hero.

1857: Joseph Conrad (Top 200: Heart of Darkness, Nostromo)

1859: Arthur Conan Doyle (Top 200: The White Company, The Hound of the Baskervilles, The Lost World, The Valley of Fear). HiLo Hero.

1863: Anthony Hope (Top 200: The Prisoner of Zenda). Cusper.

Anarcho-Symbolist Generation (1864–73)

1865: Rudyard Kipling (Top 200: The Man Who Would Be King, Kim, With the Night Mail). HiLo Hero.

1866: H.G. Wells (Top 200: The Island of Doctor Moreau). HiLo Hero.

1870: Robert Erskine Childers (Top 200: The Riddle of the Sands)

BEST ADVENTURE LIT: Best 19th Century Adventure (1805–1903) | Best Nineteen-Oughts Adventure (1904–1913) | Best Nineteen-Teens Adventure (1914–1923) | Best Twenties Adventure (1924–1933) | Best Thirties Adventure (1934–1943) | Best Forties Adventure (1944–1953) | Best Fifties Adventure (1954–1963) | Best Sixties Adventure (1964–1973) | Best Seventies Adventure (1974–1983). I’ve only recently started making notes towards a list of Best Adventures of the Eighties, Nineties, and Twenty-Oughts.

ADVENTURERS as HILO HEROES: Katia Krafft | Freya Stark | Louise Arner Boyd | Mary Kingsley | Bruce Chatwin | Hester Lucy Stanhope | Annie Smith Peck | Richard Francis Burton | Isabella Lucy Bird | Calamity Jane | Ernest Shackleton | Osa Helen Johnson | Redmond O’Hanlon | Gertrude Bell | George Mallory | Neta Snook | Jane Digby | Patty Wagstaff | Wilfred Thesiger | Joe Carstairs | Florence “Pancho” Barnes | Erskine Childers | Jacques-Yves Cousteau | Michael Collins | Thor Heyerdahl | Jean-Paul Clébert | Tristan Jones | Neil Armstrong

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE