Save the Adventure (9)

By:

October 14, 2013

The frontier epic is an enduringly popular variety of adventure story. One could no doubt break it down into several themes — as I’ve done, elsewhere in this series, for other adventure story types. However, I’m going to present my notes on frontier epics in the form of a single post.

Thanks! To the nearly 400 adventure fans who kickstarted the SAVE THE ADVENTURE e-book club.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Index to All Adventure Lists | Introduction to Adventure Themes & Memes Series | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade

The frontier epic takes the central dilemma of all adventure — the enlightened, modern, rationalized social order vs. a passionate, authentic life — and makes it concrete. Civilization is a place, according to the frontier epic. Once you’ve physically crossed its border or traveled to its far frontier, civilization’s restrictive forms and norms begin to break down. The invisible prison limned by the frontier epic is HABITUS, the objectification of social structure at the level of individual subjectivity — which is to say, the individual’s internalization and normalization of values, dispositions and expectations. Out on the frontier, habitus breaks down. Forms and norms that your civilization encourages you to regard as natural, permanent, and inevitable are revealed as unnatural, impermanent, and evitable.

The downside of this sort of thing is authenticity-mongering, which is rife in this variety of adventure. (NB: I agree with those existentialists who say that authenticity is something you invent.)

Nostalgie de la boue. Martin Green says of the frontier epic that unlike the Robinsonade, which is a dream about starting traditional life, again, from scratch, far from civilization, in some sense purified, the Frontiersman story is about starting a new life that is morally grosser in some ways.

Notes about the adventure vs. the epic:

* According to some scholars, e.g., Michael Nerlich, the adventure mindset, or mentalité is pre-modern. It began in the high Middle Ages (late 12th century). Nerlich notes that adventurers in classical antiquity — like Odysseus — were not celebrated as exemplary human beings, nor was the quest for adventure elevated to the meaning of life; adventure was something inflicted upon you by fate or the gods, something to be endured (in Latin, adventura means “that which happens to a person”). In classical antiquity, an adventure changes neither the adventurer nor the social order; the adventurer is passive, suffering. But the late 12th-century adventure is a semi-anarchic ideological orientation, one which values a certain amount of disorder (as a harbinger of change), the deliberate leaving of the known for the unknown, acceptance of every sort of risk (from the physical to the economic, social, cultural), chance and surprise instead of fate and predestination, recognition and admiration of “the other” (other races, languages, manners, societies, necessities, desires), and irrationalism (sacrifice, non-sense, play).

* The ideology of adventure was forged under specific (revolutionary, antifeudal) historical circumstances. Knightly/chivalric adventure-thought emerged in opposition to (a) the emergent absolutist monarchy, and (b) the rising social and economic power of the medieval borjois. (The bourgeoisie later assimilated this ideology to denote their own capitalistic commerce and production: see the installment of this series on the theme of Un-Alienated Work). Until the late 12th century, knights weren’t necessarily noble or distinguished — they were fighters. But during the 12th century they emerged as a powerful social caste — whose position was threatened by the revolutionary, antifeudal alliance between monarchy and bourgeoisie. In the late 12th century, e.g., in the verse romances of Chrestien de Troyes about King Arthur and his Round Table, adventures are undertaken on a voluntary basis — they are sought out, quested for. The quest if glorified; and so is the hero. Adventure now demands and celebrates voluntary daring, the quest for extraordinary events with unpredictable risk, and honor. Self-testing as an end in itself, with no specific task (and even if it disrupts the social order), is the knight’s ethical duty. The person who actively seeks out danger is celebrated as a higher form of human being than the contemptible city-dwelling bourgeoisie. The underlying message is politically, socially, economically pointed: the bourgeoisie is subordinate to the adventure-seeking knightly caste; and the monarch depends on the knightly caste for protection.

* The allegorical modern epic emerged during the Renaissance — Italian poets commingled the epic tradition derived from Old French poem with the Arthurian romance tradition) as a resistance to the knightly adventure romance; the epic warrior was a more acceptable hero, to the absolutist monarchies, than the knight-errant. For example: Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532 onwards); Sidney’s Arcadia (1570s_; Spenser’s nationalistic, crypto-Protestant/imperialist epic poem Faerie Queene (1590–96); Don Quixote (1605, 1615); Milton’s Paradise Lost; El Cid; Coleridge and Hopkins; Longfellow’s Hiawatha.

Other notes about epics:

* Tone tends to be dignified, slightly melancholic or stoic; diction is elevated in style; many figures of speech.

* The narrative is focused on the exploits of a hero who represents the cultural values of a race, nation, or religious group.

* The action takes place in a vast setting, and covers a wide geographic area. The setting is frequently some time in the remote past. Heroic explorations. Sublime experience of forests, prairies, oceans, mountains, ruins, wars, floods.

* The action contains superhuman feats of strength or military prowess. (In modern epics: sharpshooters, amazing trackers, etc.)

* The narrative often starts in medias res. Subsequently, the earlier events leading up to the start of the poem will be recounted in the characters’ narratives or in flashbacks.

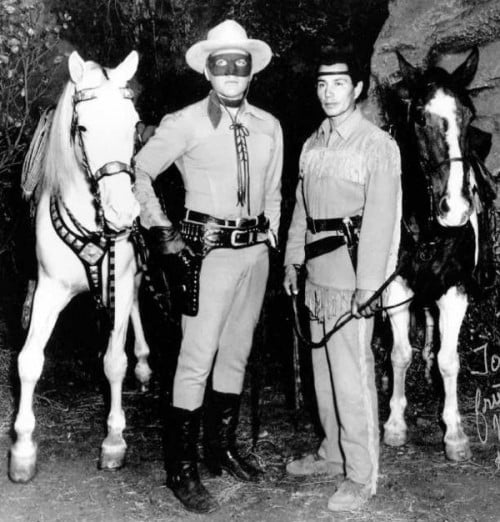

* In frontier epics, specifically, there is often a close friendship forged between two heroes of different cultures.

* James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales set the precedent for this sub-genre of adventure. Natty Bumppo first appears in the 1823 novel The Pioneers. Bumppo is a frontiersman who moves between civilization and savagery. Fleeing civilization, he seeks the consolations of nature and/or solitude and/or an alien tribal culture. Bumppo is the child of white parents, but he grew up with Native Americans. He respects his forest home and all its inhabitants. He and his Mohican “brother” Chingachgook champion goodness by trying to stop the incessant conflict between the Mohicans and the Hurons. He is known as “Deerslayer” in The Deerslayer, “Hawkeye” and “La Longue Carabine” in The Last of the Mohicans, “Pathfinder” in The Pathfinder, “Leatherstocking” in The Pioneers, and “the trapper” in The Prairie.

PS: Mark Twain mocks the Leatherstocking tales viciously in this essay. Also see the Mighty Whitey trope: “A common trope in 18th and 19th century adventure fiction, when vast swathes of the world were being explored and properly documented by Europeans for the first time, Mighty Whitey is usually a displaced white European, of noble descent, who ends up living with native tribespeople and not only learns their ways but also becomes their greatest warrior/leader/representative.”

PPS: Montaigne was the first to apply the Noble Savage trope to the North American Indians, and the trope itself goes all the way back to ancient Greek writers spoke of the Gauls this way. At the time, Cooper was praised for presenting Chingachgook and his son Uncas as heroes; today, we see Cooper’s positive depiction of Native Americans as just another stereotype.

* Cooper’s 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans.

* Cooper’s 1827 novel The Prairie.

* Edgar Allan Poe’s 1838 adventure at sea The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, the great fabulist’s only complete novel. A gruesome and symbolic parable… about what?

* Cooper’s 1840 novel The Pathfinder.

* Cooper’s 1841 novel The Deerslayer.

* G.A. Lawrence’s Guy Livingstone (1857) set the pattern for Ouida — it has episodes in which Ireland serves as the frontier where Englishmen can and must behave like men of empire.

* Ouida’s 1867 novel Under Two Flags — which takes place on the white frontier of North Africa. The hero feels morally and emotionally on the side of those he fights against. Adapted as a movie in 1936.

* Captains Courageous is an 1897 novel, by Rudyard Kipling, that follows the adventures of fifteen-year-old Harvey Cheyne Jr., the spoiled son of a railroad tycoon, after he is saved from drowning by a fishing boat in the north Atlantic.

* Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel Heart of Darkness is a sardonic inversion.

* John Buchan’s 1910 adventure novel Prester John. Set in Africa.

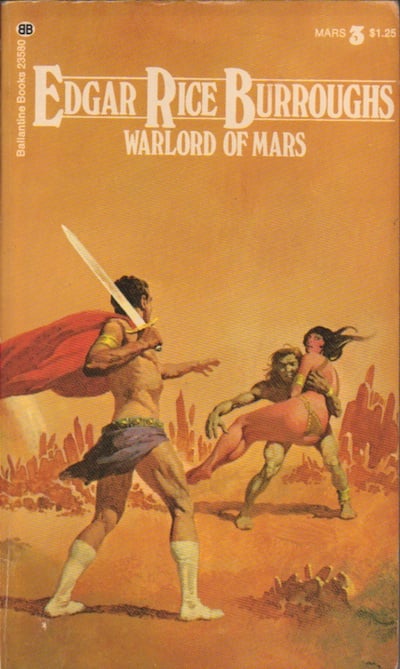

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes (1912)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Return of Tarzan (1913)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Beasts of Tarzan (1914)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Son of Tarzan (1914)

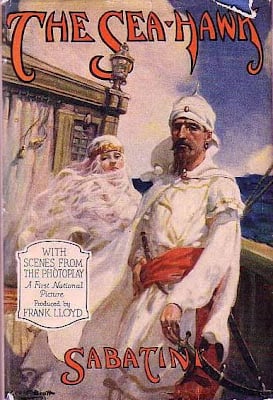

* Rafael Sabatini’s 1915 novel The Sea-Hawk — not to be confused with Errol Flynn adaptation. This one is about life on the frontier, and a westerner’s friendship with Moors.

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar (1916)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Jungle Tales of Tarzan (1916, 1917)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan the Untamed (1919, 1921)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan the Terrible (1921)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the Golden Lion (1922, 1923)

* Henry Stacpoole’s 1923 romance novel The Garden of God (sequel to his 1908 novel, The Blue Lagoon), in which Dick (child of the couple from the first novel) meets Katafa, a Spanish girl who was raised by natives.

* E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India (1924) — a sardonic inversion of this sub-genre?

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the Ant Men (1924)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle (1927, 1928)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the Lost Empire (1928)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan the Invincible (1930–1931)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan Triumphant (1931)

* Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo (1931/1946) should be mentioned here.

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the City of Gold (1932)

* Hergé’s Tintin in America (1932/1945) should be mentioned here.

* The Lone Ranger and Tonto first appeared in 1933 in a popular Detroit radio serial. The show spawned a series of books, an equally popular television show that ran from 1949 to 1957, and comic books and movies.

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the Lion Man (1933, 1934)

* James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon.

* LeRoy W. Snell’s 1934 YA novel The Lead Disk — A Story of the Northwest features all the classic earmarks of the frontier epic. It is a terrific read.

* Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust (1934) — sardonic inversion?

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the Leopard Men (1935)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan’s Quest (1935, 1936)

* Hergé’s The Blue Lotus (1936/1946) should be mentioned here. Tintin’s friendship with Chang marked a new, less racist — even anti-racist — phase for Hergé.

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan the Magnificent (1936, 1937)

* Hergé’s The Broken Ear (1937/1943) should be mentioned here.

* Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan and the Forbidden City (1938)

* Paul Bowles’s The Sheltering Sky (1949) — sardonic inversion?

* Hergé’s Land of Black Gold (1950) should be mentioned here.

* Voss (1957) is the fifth published novel of Patrick White. It is based upon the life of the nineteenth-century Prussian explorer and naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt who disappeared whilst on an expedition into the Australian outback.

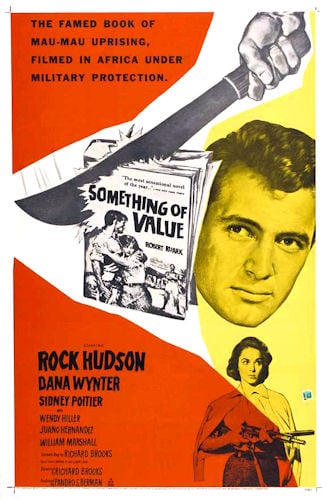

* Something Of Value is a 1957 drama directed by Richard Brooks and starring Rock Hudson and Sidney Poitier. The movie, based on the book of the same name by Robert Ruark, portrays the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya. It stars Rock Hudson as a colonial and Sidney Poitier as a native Kenyan who grew up together but have drifted apart.

* Hergé’s Red Sea Sharks (1958) should be mentioned here.

* Not exactly an adventure, but: Nigerian author Chinua Achebe’s 1958 novel Things Fall Apart is set in a frontier-type setting — a fictional village in Nigeria — the twist being that the visiting outsider is an insider: Okonkwo, a leader and local wrestling champion, who has been away in exile for seven years and returns to find everything changed by Christians.

* Not an adventure, exactly, but: Jack Kerouac’s 1958 novel The Dharma Bums is a kind of frontier epic. The frontier being America’s west coast (Kerouac is an east coaster), and the native guide being Zen Buddhist Japhy Ryder (Gary Snyder). Ray Smith (Kerouac) is torn between the civilized city life (jazz clubs, poetry readings, drunken parties) and the frontier life exemplified by Japhy (bicycling, mountaineering, hiking, hitchhiking).

* Saul Bellow’s 1959 novel Henderson the Rain King is a sardonic inversion of this sub-genre.

* Hammond Innes’s 1960 adventure novel The Doomed Oasis — in which a westerner and an Arab become comrades.

* The Sand Pebbles is a 1963 novel by Richard McKenna about a Yangtze River gunboat in 1926. The protagonist, engine mechanic Jake Holman, teaches his Chinese workers – he refuses to call them “coolies”– to master the ship’s machinery by understanding it, not just “monkey see, monkey do.”

* James A. Michener’s 1963 novel Caravans. Mark Miller, is stationed in Kabul after WWII and is given the assignment of an investigation to find a young woman who has disappeared after her marriage to an Afghan national thirteen months previously. During his journey, Miller comes to a deeper understanding of the complexities and nuances of contemporary Afghan life.

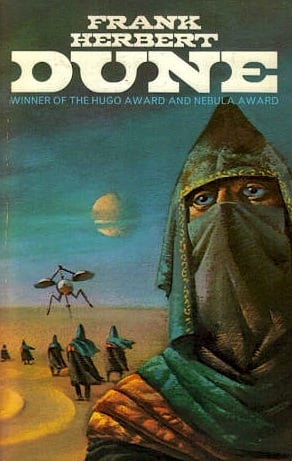

* Frank Herbert’s 1965 sci fi novel Dune.

* Ronald Johnston’s 1965 thriller Danger at Bravo Key takes place on an uninhabited Caribbean island, and the protagonist is a white American with a Caribbean islander sidekick. But there’s a twist — the sidekick turns out to be quite sophisticated, accomplished, and wealthy!

* Lionel Davidson’s 1971 novel Smith’s Gazelle should be mentioned here.

* The 1975 novel Shogun, by James Clavell, is a sardonic inversion of this genre. While John Blackthorne does eventually integrate into Japanese society, he has a lot of difficulty learning the new ways, becomes only moderately competent, does not impress people, and is usually irrelevant.

* The 1990 movie Dances with Wolves is a middlebrow version of this sub-genre.

* TBD

* TBD

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Index to All Adventure Lists | Introduction to Adventure Themes & Memes Series | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series) | Save the Adventure (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE