RADIUM AGE: 1912

By:

July 10, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

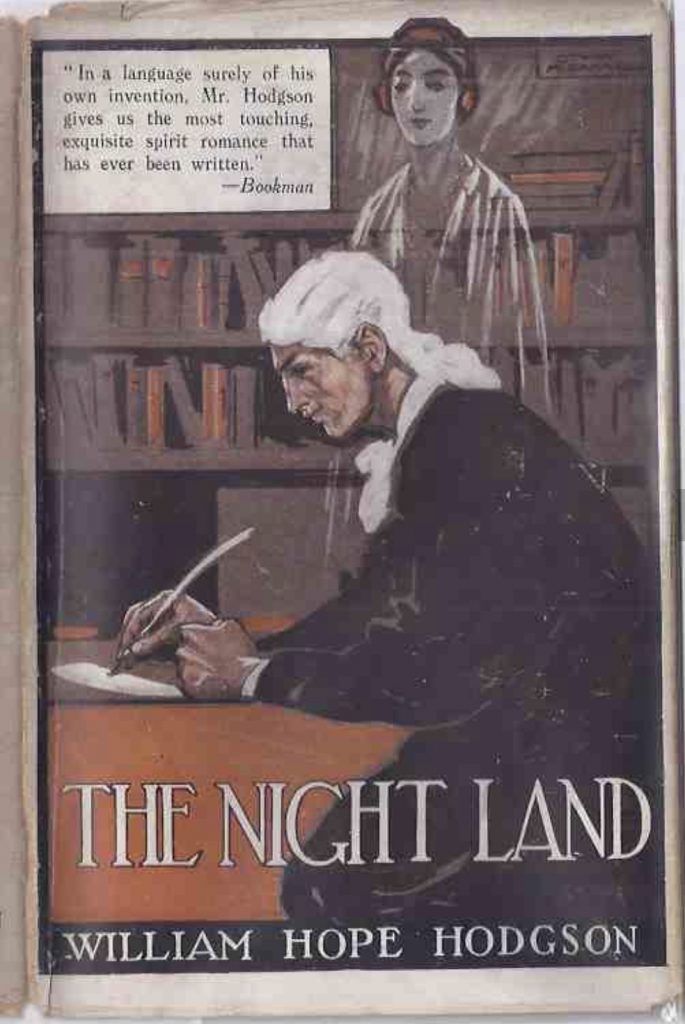

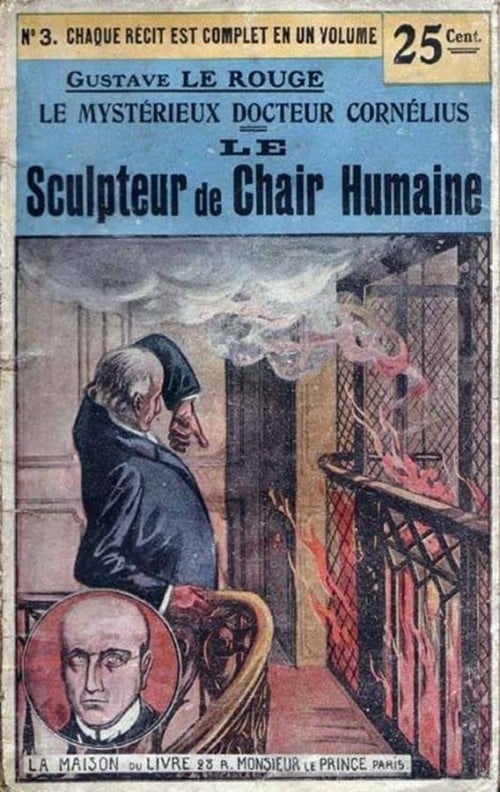

As I suggested in a 2010 post for io9.com, the year 1912 was a boffo one for the emergent sf genre. British readers, that year, enjoyed: William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, set on a frozen future Earth whose human inhabitants live in an underground redoubt surrounded by monstrous invaders from another dimension; Kipling’s As Easy as A.B.C., set in a future world dominated by an international Aerial Board of Control; and Sax Rohmer’s first Fu Manchu story, “The Zayat Kiss.” Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World was the first of several thrillers about Prof. George E. Challenger and companions. In France, meanwhile, Le Mystérieux Docteur Cornelius, by French SF author Gustave Le Rouge, pitted an alliance of heroes against a mad-scientist-led criminal empire.

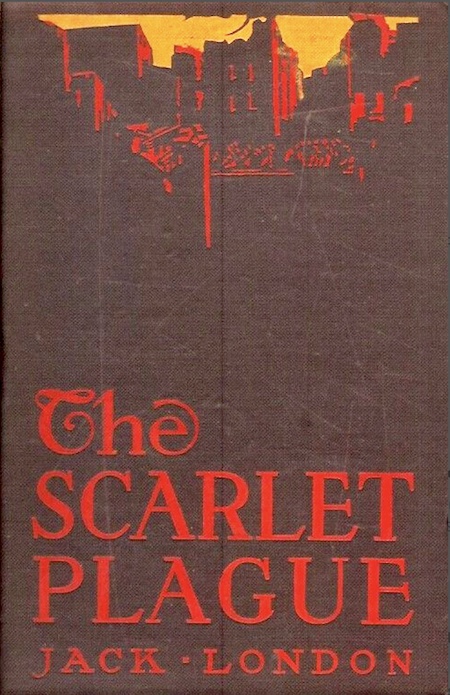

Also: The Vacant World, the first part of George Allan England’s Darkness and Dawn trilogy, in which two modern people wake up a thousand years after the Earth has been devastated by a meteor; The Second Deluge, Garrett P. Serviss’ adventure story in which a modern Noah’s warnings about an apocalyptic flood are proven correct (serialized 1911–1912, see 1911 installment of this series); and Jack London’s post-apocalyptic The Scarlet Plague was first serialized.

Most important, perhaps, was All-Story Magazine‘s serialization of Under the Moons of Mars, an epic pulp adventure inspired by the Mars-is-dying speculations of Percival Lowell, as well as Tarzan of the Apes by the same author. Because Edgar Rice Burroughs’s stories were wildly popular with readers, Munsey’s magazines, especially All-Story, would increasingly focus on fantastic adventures — thus contributing significantly to the development of sf. Along with George Allan England’s Darkness and Dawn series, Burroughs’s stories issued in what Moskowitz calls the era of the pulp scientific romance.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1912.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1912, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: MARSQUAKE | SPACESICKNESS (H. Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+ in Modern Electrics).

- William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land (1912). In the far future, what remains of the human population dwells deep below the Earth’s frozen surface in a pyramidal fortress-city that for centuries has been surrounded by giants, “ab-humans,” enormous slugs and spiders, and malevolent Watching Things from an alien dimension. The unnamed narrator, along with apparently every other surviving human, lives trapped in the Last Redoubt, an eight-mile-high metal pyramid-city constructed by their ancestors using now-forgotten technologies. The pyramid is protected from the Slayers, who surround and observe it constantly, by mysterious Powers of Goodness, and also by a massive force-field powered by the “Earth Current” — a Tesla-esque force drawn from the planet itself. When the narrator receives a telepathic distress signal from a young woman whom (in a previous incarnation) he’d once loved, he sallies forth on an ill-advised rescue mission — into the uncharted and unfathomable Night Land. Fun fact: “One of the most potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written.” — H.P. Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927). Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Erik Davis.

- Gustave Le Rouge’s Le Mystérieux Docteur Cornelius stories (1912–13). Dr. Cornelius Kramm is a brilliant, New York- and Paris-based cosmetic surgeon (nicknamed the “Sculptor of Human Flesh”) who, along with his brother Fritz, secretly rules an international criminal empire called the Red Hand. One of Cornelius’ top agents is Baruch Jorgell, a sadistic sociopath; Dr. Cornelius uses his skills as a surgeon to alter Jorgell’s appearance, making him unrecognizable. The Red Hand’s growing influence — Le Rouge’s saga was serialized in eighteen volumes — leads to the creation of an alliance of scientists, industrialists, and adventurers who fight back. There is a romance angle: One of the adventurers, Harry Dorgan, is in love with Baruch’s sister. After a globe-hopping battle, the Red Hand is defeated and Dr. Cornelius killed — or is he? Fun fact: The Dr. Cornelius stories, in order, are L’Énigme du Creek Sanglant, Le Manoir aux Diamants, Le Sculpteur de Chair Humaine, Les Lords de la Main Rouge, Le Secret de l’Île des Pendus, Les Chevaliers du Chloroforme, Un Drame au Lunatic Asylum, L’Automobile Fantôme, Le Cottage Hanté, Le Portrait de Lucrece Borgia, Coeur de Gitane, La Croisière du Gorill-Club, La Fleur du Sommeil, Le Buste aux Yeux d’Émeraude, La Dame aux Scabieuses, La Tour Fiévreuse, Le Dément de la Maison Bleue, and Bas les Masques.

- William Hope Hodgson’s The Dream of X. An abridged version of Hodgson’s 1912 proto-sf novel The Night Land. The abridgment was originally published as part of the chapbook collection Poems and the Dream of X in 1912 by R. Harold Paget. A very early use of “X” as a standalone letter in a genre fiction title, as far as I can tell.

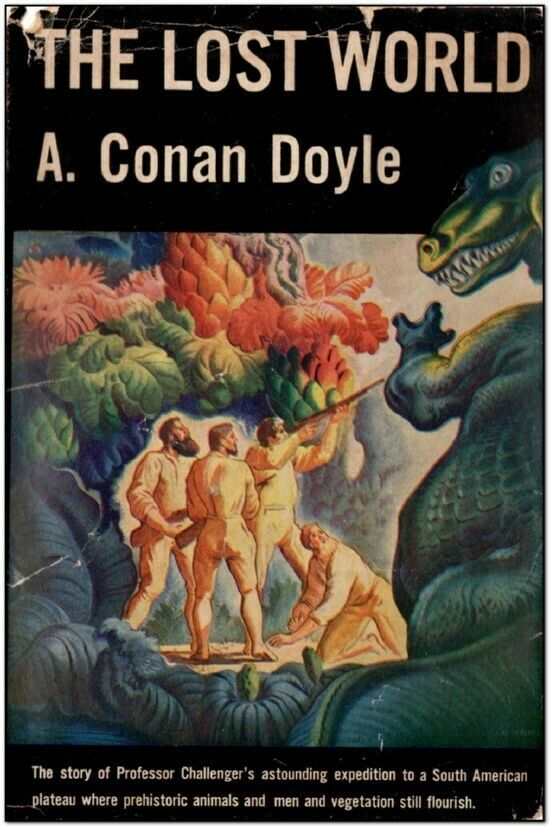

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912). Having assembled a crew of adventurers, the brilliant, blustering physiologist and physicist Prof. Challenger journeys to a South American jungle… in search of a lost plateau crawling with iguanodons. It’s a ripping yarn — the first popular dinosaurs-still-live tale, prototype for everything from King Kong to Jurassic Park. At the same time, however, it’s a philosophical novel, one which animates — in a thrilling, humorous fashion — the author’s obsessive drive (also seen in his Sherlock Holmes stories) to reconcile the claims of logical reason and intuition. Challenger’s foil, the respected zoologist Professor Summerlee, is an avatar of the inductive method of reasoning; we first meet him when he rises from the audience at a lecture in order to accuse Challenger of making non-testable assertions. Although Summerlee is an admirable figure, in the end his refusal to accept any facts that haven’t been revealed by means of instruments and techniques of observation and experiment make him look like a dogmatic nincompoop. Plus: Battles with proto-humanoids! Fun fact: Doyle followed up this bestselling novel with The Poison Belt (1913) and The Land of Mist (1926), as well as two short stories about Challenger. Doyle’s story helped launch a renewed interest in Lost-World stories in pulp proto-sf.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars (serialized 1912; in book form, 1917). Transported to Mars — via something like astral projection — ex-soldier John Carter finds himself embroiled in a war between the Red and Green Martians. The barbaric, nomadic Green Martians are 15 feet tall, with six limbs; they inhabit the abandoned cities of Barsoom (that is, Mars). The Red Martians, meanwhile, are civilized humanoids, organized into city-states that control Barsoom’s water. Carter’s unusual coloring, and the extraordinary strength he is afforded by the planet’s weak gravity, make him uniquely capable of forming alliances among honorable members of both Barsoomian peoples. He falls in love with Dejah Thoris, beautiful daughter of a Red Martian chieftain, and rescues her from both Green and Red Martians before leading a Green Martian army against the enemy of Thoris’s state. Fun facts: Serialized pseudonymously, in the same year that Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes appeared, this is the first in the author’s popular “Barsoom” planetary romance series. It was originally titled Under the Moons of Mars. PS: I might be in the minority, on this subject, but I quite enjoyed the book’s 2012 Hollywood adaptation, John Carter.

- William Hope Hodgson’s “The Derelict” (1 December 1912 Red Magazine), in which an abandoned ship is found to be covered by a single dangerous, fungoid living organism, presumably evolved over time from chemicals aboard the ship in a hot, damp climate.

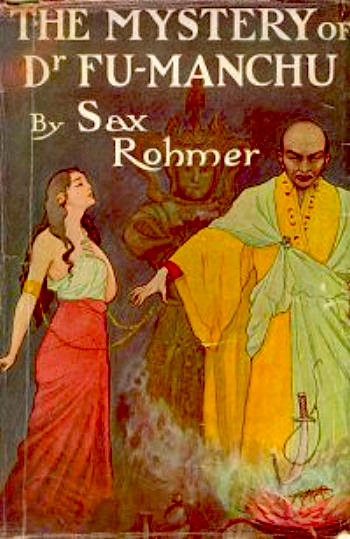

- Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1912—1913). In this first Fu Manchu novel, assembled in 1913 from stories published in magazines during 1912, colonial police commissioner Nayland Smith is in hot pursuit of Fu Manchu, an agent of a Chinese secret society, the Si-Fan. A brilliant scientist and criminal mastermind, Fu Manchu has relocated from China and Burma to East London’s Limehouse district, from where — Smith believes — he is orchestrating a wave of assassinations targeting Western imperialists. Oh, and he appears to be kidnapping Europe’s best engineers and smuggling them back to China for some nefarious purpose, too! Fun fact: Rohmer’s Fu Manchu character would inspire racist depictions of Asian sci-fi/fantasy villains from Ming the Merciless to Dr. No. The character was also featured in movies, TV, radio, comic strips, and comic books through the middle of the century; these latter entertainments — which depicted Rohmer’s villain with a long, drooping mustache (not mentioned in the books), has led to that style of facial hair becoming popularly known as a “Fu Manchu.”

- George Allan England’s The Vacant World (serialized 1912). The first part of the author’s Darkness and Dawn trilogy. When engineer Allan Stern and his beautiful secretary, Beatrice, wake up on the upper floor of a ruined Manhattan skyscraper, over a thousand years in the future, they are understandably confused. What happened? It’s a Rip Van Winkle story in which an asteroid has destroyed most life on Earth; New York lies in ruins. Wild animals and savage, mutated humans roam the streets — alas, I’m sorry to report that they are African-Americans. Allan uses his skills to make explosives, build bridges, fly bi-planes, and so forth; Beatrice joins him in discussions of how to rebuild civilization along utopian lines. This is pulp fiction, with a socialist edge. It’s not well-written, but it’s of historical interest, because — along with Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague — it’s an early post-apocalyptic yarn. Listed in the Cambridge Companion to SF chronology, singled out in Moskowitz’s A History of the Scientific Romance. Fun fact: England unsuccessfully ran for Governor of Maine as a socialist. The other books in the Darkness and Dawn trilogy are Beyond the Great Oblivion (1913) and Afterglow (1914).

- Mabel Winifred Knowles’s A Message from Mars (as by Lester Lurgan). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- George Randolph Chester’s The Jingo.”Lost race with satirical elements; shipwrecked American lands on island populated by classical Greeks; modern innovations, and complications, ensue. A variant on Twain’s Connecticut Yankee, romanticism meets material positivism.” – Robert Knowlton. “In a delightful spoof on the lost-race motif, the jingoistic Jimmy Smith, representative of the Eureka Manufacturing Company, brings ‘improvements’ to the kingdom of Isola in the Antarctic.” – Anatomy of Wonder

- Max Beerbohm’s A Christmas Garland — Christmas-themed parodies of contemporary authors, including proto-sf authors. His Kipling send-up has a London policeman pounce upon a red-robed “airman” seen emerging suspiciously from a chimney-pot. The neologism-studded gloom of Thomas Hardy’s Napoleonic verse epic The Dynasts is echoed by a Beerbohm “sequelula” that opens in the Void: “Our own Solar System is visible, distant by some two million miles.” To Hardy’s chorus of observing spirits, humanity appears as “parasites by which, since time began,/Space has been interfested.” Max’s H.G. Wells spoof envisions a future utopia where Christmas has become General Cessation Day, that happy time when old folk walk in stately procession to the lethal chambers. Thus they joyously “‘make way’ for the beautiful young breed of men and women who, in simple, artistic, antiseptic garments, are disporting themselves so gladly on this day of days.” Also parodies Chesterton, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, Hilaire Belloc, GB Shaw, etc.

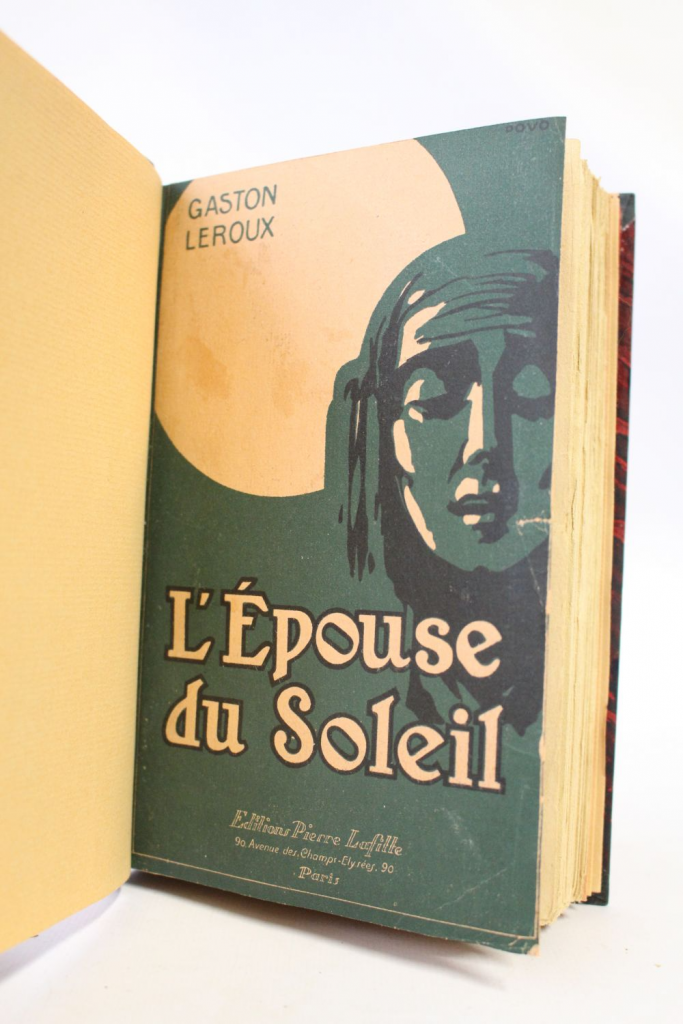

- Gaston Leroux’s L’Espouse de Soleil (March-August 1912 in Je Sais Tout (translated November 1914 in Blue Book as The Bride of the Sun. Dick Montgomery hopes to marry his fiancé, Maria-Teresa de la Torre, the daughter of a Spanish marquis, in Peru. When Maria-Teresa discharges a group of Quichua Indians working in the household, including Huascar, Maria-Teresa is kidnapped. It is rumored that she will be sacrificed to the new Sun King of the country’s Indian population. When Huascar offer to help Dick save Maria-Teresa, a rescue mission into lost-world territory begins. A key influence on Hergé’s Tinton adventure The Prisoners of the Sun.

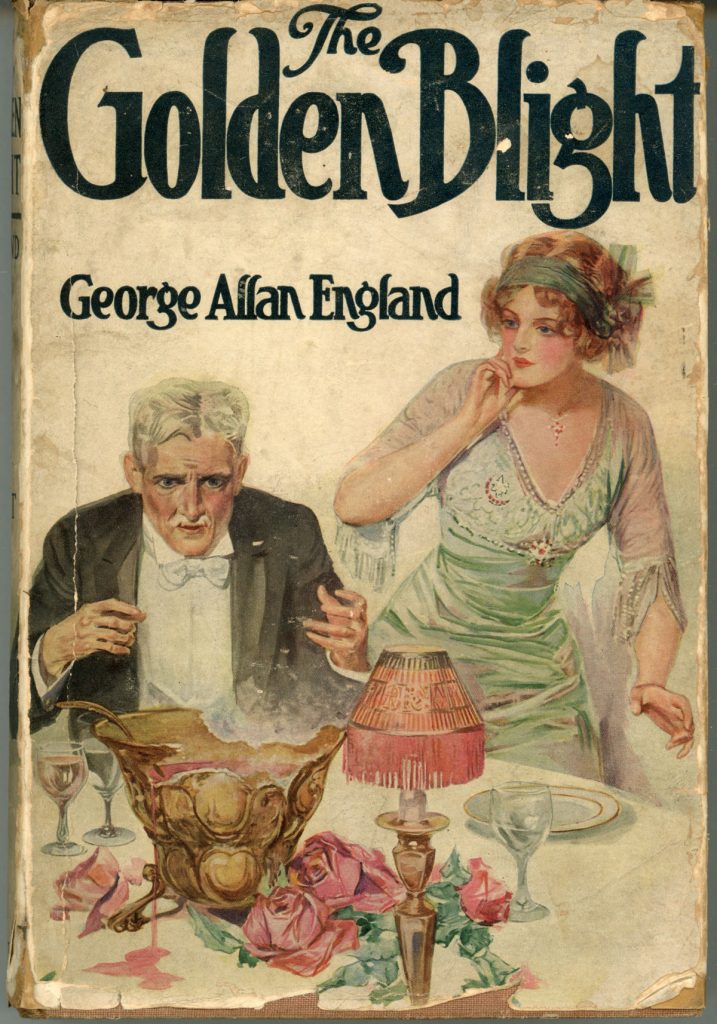

- George Allan England’s The Golden Blight — a ray that temporarily changes gold to ash. In the author’s own summary: “Storm discovers a method of turning all the world’s gold-supply into ashes. He demands that Murchison shall take steps to put an end to war, on pain of ruining him and the entire capitalist class, and overthrowing capitalism. Murchison refuses, and defies him. Storm demonstrates his power. At a great banquet given by Murchison, Storm projects his power and turns all the gold-plate and ornaments to dross. A hasty meeting of financiers is called, and plans laid to kill Storm. But he foils all plots, and continues his work of destruction, with repeated demands that the capitalists yield, etc.” In addition to being anticapitalist, I hear it’s quite a racist story. “More lively and better written than most of England’s socially oriented fiction, but with many long essay sections on war and the munitions industry.” – Bleiler

- Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague (1912). Outside the ruins of San Francisco, a former UC Berkeley professor recounts the chilling sequence of events — a gruesome pandemic which killed nearly every living soul on the planet, in a matter of days — which led to his current lowly state. Modern civilization has fallen, and a new race of barbarians, descended from the world’s brutalized workers, has assumed power. Over the space of a few decades, all learning has been lost. In the post-apocalyptic social order, women are degraded and beaten: Vesta Van Warden, wife of the richest man in America before the plague, we learn from the ancient James Howard Smith, became the chattel of one of her former servants, a man known only as Chauffeur. Predatory nomads — members of the Chauffeur Tribe — named Hoo-Hoo and Hare-Lip roam among the ruins of San Francisco. And Smith, formerly a professor of literature at UC Berkeley, is reviled by his juniors for being literate. Fun fact: Reissued by HiLoBooks with an Introduction by Matthew Battles.

- Gustave Le Rouge’s “Bas les masques!”, “Cœur de gitane”, and “L’automobile fantôme” — proto-sf stories (I think) from this year.

- Jacque Morgan’s “The Feline Light and Power Company is Organized” — first in a series of humorous invention stories. Seems silly.

- John N. Raphael’s Up Above, the Story of the Sky Folk. Raphael was a Uruguayan-born translator (mostly of French plays), Paris correspondent for several papers, and author. Based on Renard’s Le Peril Bleu, as Raphael acknowledges. In the near future, vast spaceships manned by invisible aliens are abducting humans and various flora and fauna. Blood falls like rain from the skies. (Published in another version in 1915.)

- Paul Scheerbart’s “Malvu the Helmsman” — German proto-sf story. Collected in The Black Mirror (Wesleyan). One of his “astral” novelettes, a marvelous, poetic conte philosophique from a turn-of-the-century bohemian mystic who has more in common with the writings of the French Symbolists than the Vernelike Lasswitz.

- Francis Lynd’s Scientific Sprague — the efforts of an engineer-scientist to solve a number of mysteries and crimes that threaten a small western railroad. Not sf, exactly. But a cool cover.

- Edward Mandell House’s Philip Dru: Administrator: A Story of Tomorrow, 1920-1935 is a futuristic political novel published anonymously an American diplomat, politician, and presidential foreign policy advisor. A benevolent dictator imposes a corporate income tax, abolishes the protective tariff, and breaks up the ‘credit trust — a remarkable adumbration of Woodrow Wilson and his first term. There are other reforms outlined, too: workmen’s insurance law, co-operative marketing and land banks, free employment bureaus, and an 8-hour work day.

- Rudyard Kipling’s “‘As Easy as A.B.C’: A Tale of 2150 AD” (March-April 1912 The London Magazine), later included in A Diversity of Creatures (coll 1917). A somewhat dystopian vision in which agents of the A.B.C. fly to Chicago to deal with a revolt of the local underclass, whose demands for a return of democracy have generated attacks by the rest of the population. Incidental sf devices include an electrical precursor of the force field. The Pax Aeronautica vision – though not necessarily the political view it argues – is derived at least in part from H G Wells. Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2012.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s The Star-Treader and Other Poems — which the SFE describes as “sf-tinged but fustian-choked poems.” “The Star-Treader” is collected in Sense of Wonder: A Century of Science Fiction (2011, ed. Leigh Ronald Grossman).

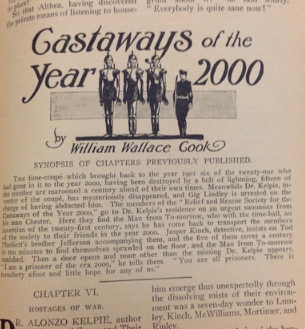

- William Wallace Cook’s Castaways of the Year 2000. Moskowitz’s History of the Scientific Romance says this sequel to Cook’s A Round Trip to the Year 2000 was popular, and that it contains significant social criticism despite its lighthearted mood.

- Some of Charles M. Doughty’s poetry is of sf interest. The Clouds describes a successful airborne invasion of England; the SFE calls it one the most arcane future war tales ever told. See 1909 for a note on The Cliffs. Excerpt from The Cliffs published at HILOBROW in 2022.

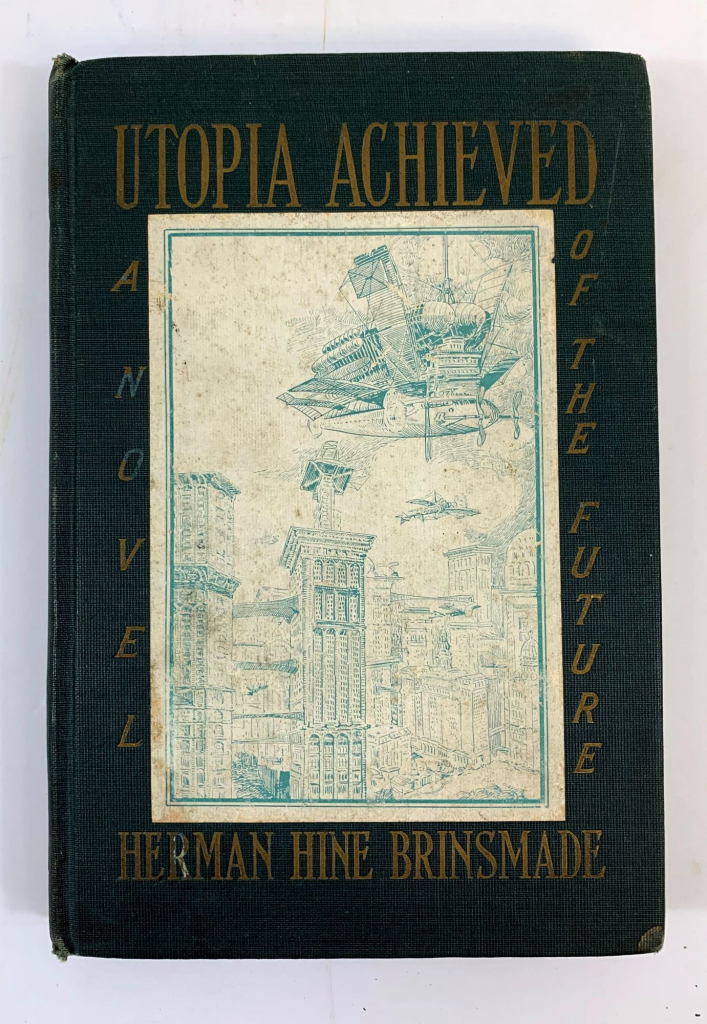

- Herman Hine Brinsmade’s Utopia Achieved — about a futuristic NYC. Set in 1960 and had a storyline that advocated for the single tax. The story described a city of the future where people eat an efficient vegetarian diet.

- Wilhelm Lamszus’s Menschenschlachthaus: Bilder von kommenden Krieg (1912; trans Oakley Williams as The Human Slaughter-House (Scenes from the War That Is Sure to Come) 1913 UK). German educator and author, dismissed from his teaching post when the Nazi regime took over, presumably because of his anti-war writings, including this novel. A prophetically horrific Near Future vision of WWI from the viewpoint of an impassioned pacifist, who undergoes a profound vision of the tortured Earth before killing himself.

- Richard Fifield Lamport’s Veeni the Master. “Science fantasy romance in which, just before life on earth is extinguished by the fires of a comet, a ‘chosen few’ are enabled by an omnipresent but non-altruistic Veeni to transfer their souls into the bodies of the human inhabitants of Zan, a planet round another star.” — Locke, A Spectrum of Fantasy

The title of Kupka’s work refers to Sir Isaac Newton, who discovered that the light of the sun is composed of the seven colors of the spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Kupka’s radiant composition incorporates circular bands of vibrating color, including the full range of the spectrum as well as white.

ALSO: Vesto Slipher is the first to discover that distant galaxies are redshifted, thus providing the first empirical basis for the expansion of the universe. Soddy’s The Chemistry of the Radioactive Elements (1912–1914) and Matter and Energy. Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious precipitates a break with Sigmund Freud. Skull of “Piltdown Man” presented to the Geological Society of London as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown form of early human. Arizona and New Mexico become states; Wilson becomes US president. The Titanic sinks; John Jacob Astor, Jacques Futrelle, and W. T. Stead, all proto-sf authors, die. Lenin and Stalin team up. Textile worker’s strike in Lawrence, Mass., shows power of the IWW. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes, Mann’s Death in Venice (Nietzschean depiction of the artist as one who lives between the poles of the abyss and sterility), Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage. Cravan publishes 5 issues of Maintenant!. Hugo Ball meets Wassily Kandinsky, Richard Huelsenbeck, Emmy Hennings; Duchamp enters a painting in the Cubists’ 1912 Salon des Indépendants: Nude Descending a Staircase*; Picasso’s The Violin. Voynich manuscript discovered. The Futurist architect Antonio Sant’Elia expressed his ideas of modernity in his drawings for La Città Nuova (The New City) (1912–1914). This project was never built and Sant’Elia was killed in the First World War, but his ideas influenced later generations of architects and artists.

*Duchamp’s never-completed manuscript 1912–1920 A l’Infinitif, also known as The White Box, references Poincaré’s writings on the fourth dimension (as well as Jouffret’s).

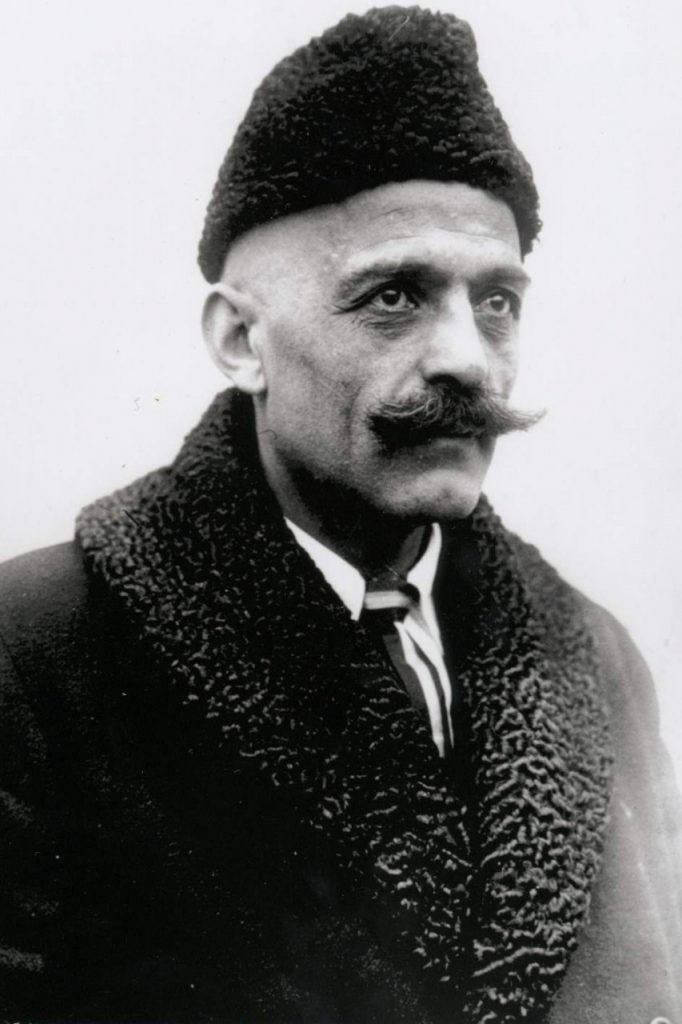

On New Year’s Day in 1912, George Gurdjieff (formerly a hyponotherapist and possibly a spy) arrived in Moscow and attracted his first students, who learned from him that most humans do not possess a unified consciousness and thus live their lives in a state of hypnotic “waking sleep” — but that it is possible to awaken to a higher state of consciousness via the “Fourth Way,” an approach to self-development he’d developed over years of travel in the East, where he’d taken an interest in the way of the fakir (self-mastery through physical struggle), the way of the monk (self-mastery through struggle with the affections) and the way of the yogi (self-mastery through struggle with mental habits). His doctrine – which seems essentially to apply “scientific” expressions of mystical intuitions with the aim of providing models of harmonious selfhood for his followers – deeply influenced figures like A.R. Orage and P.D. Ouspensky. Gurdjieff is several times referenced in Brian Aldiss’s Barefoot in the Head.

Also see this site for another take on Gurdjieff.

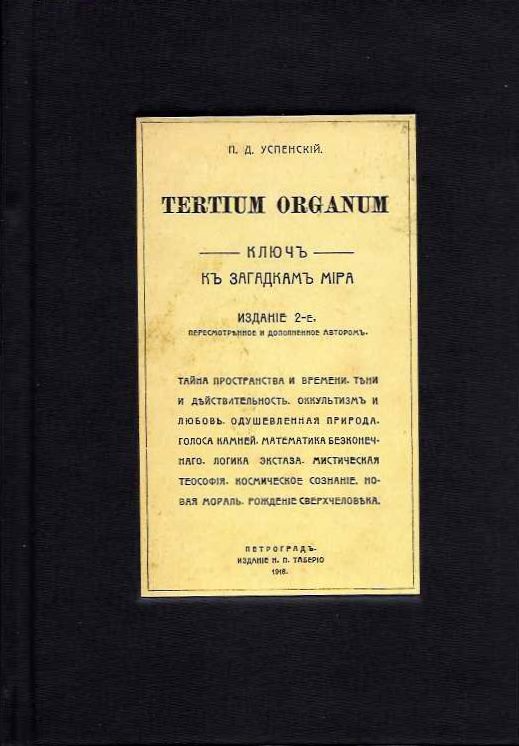

P.D. Ouspensky’s Tertium Organum: The Third Canon of Thought, a Key to the Enigmas of the World, which denies the ultimate reality of space and time and negates Aristotle’s Logical Formula of Identification of “A is A,” published this year also. Architect Claude Bragdon, who was fascinated by fourth dimension theories, would translate the book into English and publish it to acclaim. The book is a pretentious millenarian compendium of occultist clichés of the previous thirty years; however, to many artists, not just Cubists but Surrealists as well, the concept of the fourth dimension symbolized freedom from the stifling constraints of capitalist reality.

Tertium Organum purports to present a new epistomology and a new ontology in accordance with Einstein’s theory of a four-dimensional time continuum. Ouspensky opens his argument by reiterating Kant’s proof that ultimate realities cannot be apprehended by an empirical perception. (Kant had proved that basic phenomena like time and space were only extensions of the individual consciousness.) Assuming that a noumenal world exists, how can we, asks Ouspensky, perceive these ultimate realities? His solution is to turn to consciousness itself, to the intuitive faculty of the mind, for the means whereby these ultimate truths may be perceived. Such reasoning as this only confirmed what Frank himself had decided earlier – that Scientific truth, because it was relative, was inferior to Religious truth, and that scientific or empirical reasoning, when pursued as an end in itself, became destructive and analytical, breaking down the traditional integers of belief and producing nothing to take their place.

Although Ouspensky admits that, as the creatures in Plato’s cave, mortal man can never hope to fully comprehend the world of ultimate reality — “inexpressibility is the sign of truth” — he does make some tentative deductions about this world by a series of analogies. For one thing, it is a world composed of three dimensions plus the fourth dimension. Just as a dog, when he walks past a three-dimensional object, perceives its third dimension (depth) as something fleeting and transitory, so man perceives the fourth dimension (time) as something fleeting and transitory. The fourth dimension is time itself, but since it is a dimension, it is therefore static. Thus the noumenal world is a world of the Eternal Now of Hindu philosophy, a world without past or future. Since there is no duration in such a world, there is no action. And since there is no action, there can be no cause and effect. Likewise, three-dimensional qualities like size and position are nonexistent, and are replaced by subjective feelings of affinity and remoteness. There is no death in this world: everything participates in eternal life. Likewise, there is no individuation, and all share a common self: “Everything is the whole.” Contrary to traditional Platonism, the material world is not illusory — it is only the noumenal world represented imperfectly to our senses. As was previously mentioned, Ouspensky believed that the nature of this noumenal world could be known through mysticism. Any type of mysticism would suffice, he thought, from the extreme asceticism of Yoga to the ecstatic trance of the Dionysian, just as long as the conventional perception of phenomena was disrupted and “an expansion of consciousness” took place.

The book was familiar to many writers in the twenties. Philip Horton reports that the

1923 literary clique — Hart Crane, Gorham Munson, and Jean Toomer — of which Waldo Frank served as patriarch, professedly considered Ouspensky’s book to be their “bible.”

Tertium Organum describes four stages of spiritual development. These are characterized in part by the ability to perceive each of the four spatial dimensions. He described the perception of the fourth and highest stage: “A feeling of four-dimensional space. A new sense of time. The live universe. Cosmic consciousness. Reality of the infinite. A feeling of communality with everyone. The unity of everything. The sensation of world harmony. A new morality. The birth of a superman.”

Also in 1912: Rudolf Steiner breaks away from the Theosophical Society to found an independent group, which he names the Anthroposophical Society. Like many other occultists at the turn of the twentieth century, Steiner felt that he was pulling back the curtain on materialistic science so that all could see its spiritual context. Regarding evolution, for example, Steiner posited an evolutionary drama of cosmic proportions. His cosmology, like Blavatsky’s, is complex, even dizzying, and reiterates ancient motifs now deemed occult. Betraying a Pythagorean fondness for certain basic numbers, Steiner talked of the seven states of consciousness, the seven life kingdoms or conditions, the four elements, the three creative functions, the ten cabalistic sephiroth, the nine angelic orders, and so on. These orders, kingdoms, functions, and elements are linked to the planets or zodiacal constellations in a vast system of evolving consciousness.

The brainchild of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, Rayonism (sometimes translated from Russian as Rayism) developed new ways to express energy and movement. From its conception as a subset of Russian Futurism, Rayonism drew from scientific discoveries — Larionov had most likely read Marie Curie’s Radioactivity and The Discovery of Radium, both recently published in Russia — and theoretical conceptions of the fourth dimension. The adoption of transparency and fractured objects was influenced by changing understandings of the material world through the discovery of x-rays and radioactivity. The world no longer could be thought of as purely solid and concrete. This, in turn, reinforced fourth-dimensional theories of space and experience as a continuum of our observable universe. The “Rayonist Manifesto” was written in 1912. Although short-lived, Rayonism was a crucial step in the development of Russian abstract art.

The heroic age of Antarctic exploration is underway. In 1912, Morton Moyes, a member of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, was unintentionally left alone in an isolated hut in Antarctica for nine weeks. As Elizabeth Leane notes in “Locating the Thing: The Antarctic as Alien Space in John W. Campbell’s ‘Who Goes There?’, Moyes began to “think of all Antarctica as… a slow-brained sentient being bent on making a man part of itself… some it conquered, grafting them indivisibly to its body” (quote from a Moyes letter). The abject nature of the Antarctic — Leane uses Kristeva’s theory — its nature as an abyss at the border of the subject’s identity, a place where borders are breached (she points to earlier theories of Symmes Holes, in which the North Pole is like the planet’s mouth and the South Pole its sphincter and/or birth canal), a landscape both lifeless but always shrinking and expanding, shapeshifting — informed Poe’s Antarctic stories, and in pulp stories of the early- to mid-twentieth century, was embodied in horrifying alien entities that are ill-defined and lacking in fixed shape, and which threaten to dissolve the subjecthoods of their victims. Antarctic aliens in pulp sf will change shapes, leak fluids, and threaten the expeditioners’ own bodily boundaries. Not merely a generically hostile and unexplored setting, Leane concludes, the Antarctic in proto-sf of this era signifies “an instability at the margins of the subject and the margins of the world.”

William James’s Essays in Radical Empiricism — a posthumous collection includes his groundbreaking essays on “pure experience” (See 1904). James’s “radical empiricism” is distinct from his “pure experience” metaphysics. It is never precisely defined in the Essays, and is best explicated by a passage from The Meaning of Truth (1909) where James states that radical empiricism consists of a postulate, a statement of fact, and a conclusion. The postulate is that “the only things that shall be debatable among philosophers shall be things definable in terms drawn from experience,” the fact is that relations are just as directly experienced as the things they relate, and the conclusion is that “the parts of experience hold together from next to next by relations that are themselves parts of experience.” James is one of the most attractive and endearing of philosophers: for his vision of a “wild,” “open” universe that is nevertheless shaped by our human powers and answers to some of our deepest needs, but also, as Russell observed in his obituary, because of the “large tolerance and … humanity” with which he sets that vision out.

Kandinsky in 1912 (On the Spiritual in Art) assesses two dangers in contemporary art. The artist’s role is to depict spiritual truths — to get beneath realism and to express the sacred geometry of how things are. He worries that Matisse and Picasso, the artists then best known for defining the revolutionary developments in the visual arts throughout the opening decades of the twentieth century, were headed in bad directions. Matisse’s rigorous style (post-1906) that emphasisized flattened forms and decorative patterns was the right idea, but his exaggeration of color made his works merely ornamental. Picasso’s “destruction of the material object” was the right idea, but instead of revealing an underlying truth, Picasso merely scattered the destroyed object’s pieces over the canvas — creating what Kandinsky dismissively named “fantasy.”

Cubism was not essential to the progress of any major artist moving away from a representational mode to an asbtract mode — instead, they were influenced by spiritualism, and also by Symbolist painting and theory. Symbolism contained the seeds of abstract art.

Shjeldal: “Kandinsky’s art has nothing important in common with Cubism, Futurism, or the other breakout movements of the epoch. His independence of Picasso made him a crucial influence on the efforts to blow open the knitted pictorial space of Parisian modernism — first of Joan Miró and later of Arshile Gorky and the Abstract Expressionists. The formal difference is apparent in Kandinsky’s shadings of fragmented shapes: they stay flat, rarely suggesting the outward and inward tilts, the bumps and hollows, of Cubism. Any illusion of internal space is usually an effect of the “push and pull” (a famous formulation by the artist and teacher Hans Hofmann) of cool and warm colors, or the front-and-back dynamic of linear designs overlaid on colored grounds.”

Kandinsky’s ambitious theories of abstraction, promulgated in his book On the Spiritual in Art, is saturated in Theosophist mysticism, eccentric takes on science, and, most of all, accounts of his own subjective process.

Sxhjeldal approves more of Malevich and Mondrian: “Meanwhile the other cogent innovators of abstract painting, Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, each found a way, by reduction, to establish fundamental forms that yield firm and clear impressions.”

Balla’s nonreferential paintings were informed by his fascination with spiritualism. A fascination he shared with other Italian futurists.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin