The Machine Stops (10)

By:

September 23, 2015

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize E.M. Forster’s 1909 novella The Machine Stops. Published between the author’s much more famous works A Room With A View and Howards End, science fiction scholars remind us that The Machine Stops predicted the Internet and instant messaging… as well as a WALL-E-type dystopia.

It became difficult to read. A blight entered the atmosphere and dulled its luminosity. At times Vashti could scarcely see across her room. The air, too, was foul. Loud were the complaints, impotent the remedies, heroic the tone of the lecturer as he cried: “Courage! courage! What matter so long as the Machine goes on? To it the darkness and the light are one.” And though things improved again after a time, the old brilliancy was never recaptured, and humanity never recovered from its entrance into twilight. There was an hysterical talk of “measures,” of “provisional dictatorship,” and the inhabitants of Sumatra were asked to familiarize themselves with the workings of the central power station, the said power station being situated in France. But for the most part panic reigned, and men spent their strength praying to their Books, tangible proofs of the Machine’s omnipotence. There were gradations of terror — at times came rumours of hope — the Mending Apparatus was almost mended — the enemies of the Machine had been got under — new “nerve-centres” were evolving which would do the work even more magnificently than before. But there came a day when, without the slightest warning, without any previous hint of feebleness, the entire communication-system broke down, all over the world, and the world, as they understood it, ended.

Vashti was lecturing at the time and her earlier remarks had been punctuated with applause. As she proceeded the audience became silent, and at the conclusion there was no sound. Somewhat displeased, she called to a friend who was a specialist in sympathy. No sound: doubtless the friend was sleeping. And so with the next friend whom she tried to summon, and so with the next, until she remembered Kuno’s cryptic remark, “The Machine stops.”

The phrase still conveyed nothing. If Eternity was stopping it would of course be set going shortly.

For example, there was still a little light and air — the atmosphere had improved a few hours previously. There was still the Book, and while there was the Book there was security.

Then she broke down, for with the cessation of activity came an unexpected terror — silence.

She had never known silence, and the coming of it nearly killed her — it did kill many thousands of people outright. Ever since her birth she had been surrounded by the steady hum. It was to the ear what artificial air was to the lungs, and agonizing pains shot across her head. And scarcely knowing what she did, she stumbled forward and pressed the unfamiliar button, the one that opened the door of her cell.

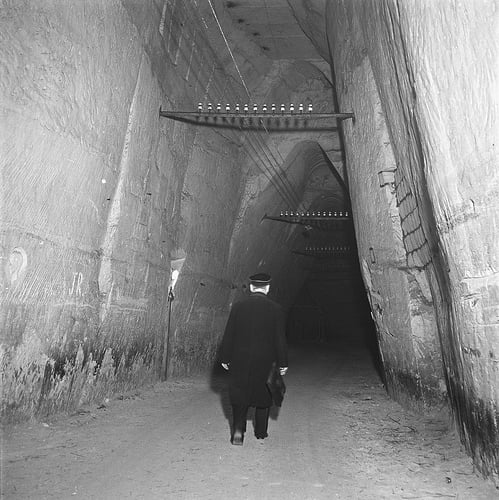

Now the door of the cell worked on a simple hinge of its own. It was not connected with the central power station, dying far away in France. It opened, rousing immoderate hopes in Vashti, for she thought that the Machine had been mended. It opened, and she saw the dim tunnel that curved far away towards freedom. One look, and then she shrank back. For the tunnel was full of people — she was almost the last in that city to have taken alarm.

People at any time repelled her, and these were nightmares from her worst dreams. People were crawling about, people were screaming, whimpering, gasping for breath, touching each other, vanishing in the dark, and ever and anon being pushed off the platform on to the live rail. Some were fighting round the electric bells, trying to summon trains which could not be summoned. Others were yelling for Euthanasia or for respirators, or blaspheming the Machine. Others stood at the doors of their cells fearing, like herself, either to stop in them or to leave them. And behind all the uproar was silence — the silence which is the voice of the earth and of the generations who have gone.

No — it was worse than solitude. She closed the door again and sat down to wait for the end. The disintegration went on, accompanied by horrible cracks and rumbling. The valves that restrained the Medical Apparatus must have weakened, for it ruptured and hung hideously from the ceiling. The floor heaved and fell and flung her from the chair. A tube oozed towards her serpent fashion. And at last the final horror approached — light began to ebb, and she knew that civilization”s long day was closing.

She whirled around, praying to be saved from this, at any rate, kissing the Book, pressing button after button. The uproar outside was increasing, and even penetrated the wall. Slowly the brilliancy of her cell was dimmed, the reflections faded from the metal switches. Now she could not see the reading-stand, now not the Book, though she held it in her hand. Light followed the flight of sound, air was following light, and the original void returned to the cavern from which it has so long been excluded. Vashti continued to whirl, like the devotees of an earlier religion, screaming, praying, striking at the buttons with bleeding hands.

It was thus that she opened her prison and escaped — escaped in the spirit: at least so it seems to me, ere my meditation closes. That she escapes in the body — I cannot perceive that. She struck, by chance, the switch that released the door, and the rush of foul air on her skin, the loud throbbing whispers in her ears, told her that she was facing the tunnel again, and that tremendous platform on which she had seen men fighting. They were not fighting now. Only the whispers remained, and the little whimpering groans. They were dying by hundreds out in the dark.

She burst into tears.

Tears answered her.

They wept for humanity, those two, not for themselves. They could not bear that this should be the end. Ere silence was completed their hearts were opened, and they knew what had been important on the earth. Man, the flower of all flesh, the noblest of all creatures visible, man who had once made god in his image, and had mirrored his strength on the constellations, beautiful naked man was dying, strangled in the garments that he had woven. Century after century had he toiled, and here was his reward. Truly the garment had seemed heavenly at first, shot with colours of culture, sewn with the threads of self-denial. And heavenly it had been so long as man could shed it at will and live by the essence that is his soul, and the essence, equally divine, that is his body. The sin against the body — it was for that they wept in chief; the centuries of wrong against the muscles and the nerves, and those five portals by which we can alone apprehend — glazing it over with talk of evolution, until the body was white pap, the home of ideas as colourless, last sloshy stirrings of a spirit that had grasped the stars.

“Where are you?” she sobbed.

His voice in the darkness said, “Here.”

“Is there any hope, Kuno?”

“None for us.”

“Where are you?”

She crawled over the bodies of the dead. His blood spurted over her hands.

“Quicker,” he gasped, “I am dying — but we touch, we talk, not through the Machine.”

He kissed her.

“We have come back to our own. We die, but we have recaptured life, as it was in Wessex, when Ælfrid overthrew the Danes. We know what they know outside, they who dwelt in the cloud that is the colour of a pearl.”

“But Kuno, is it true? Are there still men on the surface of the earth? Is this — tunnel, this poisoned darkness — really not the end?”

He replied:

“I have seen them, spoken to them, loved them. They are hiding in the mist and the ferns until our civilization stops. Today they are the Homeless — tomorrow ——”

“Oh, tomorrow — some fool will start the Machine again, tomorrow.”

“Never,” said Kuno, “never. Humanity has learnt its lesson.”

As he spoke, the whole city was broken like a honeycomb. An air-ship had sailed in through the vomitory into a ruined wharf. It crashed downwards, exploding as it went, rending gallery after gallery with its wings of steel. For a moment they saw the nations of the dead, and, before they joined them, scraps of the untainted sky.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”