PLANET OF PERIL (43)

By:

October 22, 2019

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

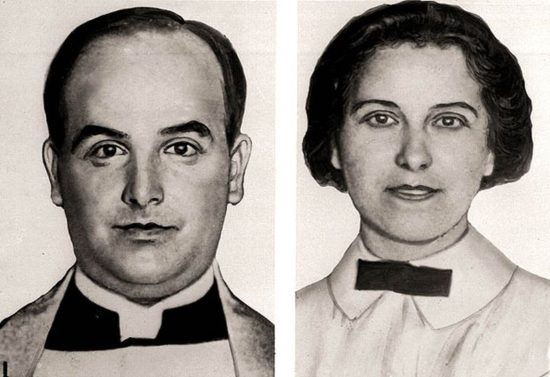

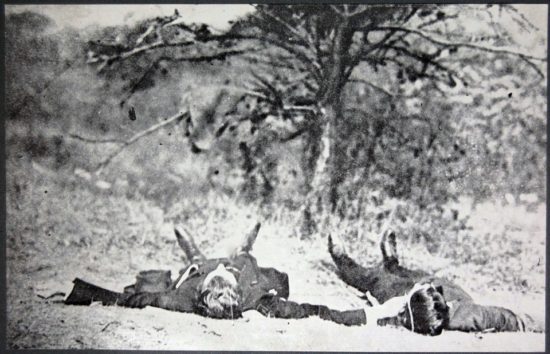

They were found on the morning of September 16, 1922, shot to death underneath a crabapple tree, just off the dirt road used as a lovers’ lane by locals in Somerset, New Jersey. They had been missing not quite 48 hours. Their bodies had been staged, lying side-by-side on their backs with their toes pointed toward the tree trunk. Her head lay on his extended right arm, while her hand lay just above his left knee. One of his engraved calling cards was propped against the sole of his shoe.

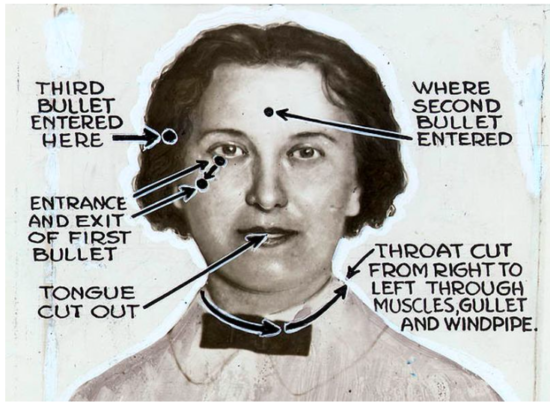

He was the Rev. Edward W. Hall, the 45-year-old rector of the Church of St. John the Evangelist in nearby New Brunswick. She was Eleanor Mills, age 34, a member of the St. John’s choir married to the church sexton, and, as everybody seems to have known, Hall’s lover. There were several signs that she bore the brunt of the killer’s animus. He had been shot once, she four times. A brown silk scarf draped neatly around her neck hid the fact that her throat had been cut so deeply she was all but decapitated. Hall’s Panama hat covered his face and underneath it, his glasses had been “placed lovingly on his nose.” Someone had closed his eyes, while Eleanor’s remained wide open in horror. An autopsy later revealed that the chorister’s tongue was missing — a persistent rumor said it had been cut out by her killer.

A selection of torn-up love letters was scattered between the bodies, and it didn’t take long for others to find their way to the newspapers. “You are a true priest,” read one of Eleanor’s letters. “You see in me merely my physical inspiration. You, the priest. Was Pan religious? God wants his people to enjoy all things deeply.” New York’s Daily News included a helpful sidebar titled “Pan”: “The Pan to which Mrs. Mills alluded was the Greek god of flocks, of pastures, of fair fruits and pregnant fields…. Pan was represented with horns, goat’s feet and ears.”

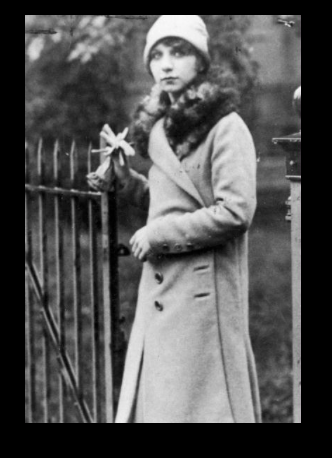

The press went wild. This was spicy stuff, these pregnant fields and horny goats and supposedly God-fearing Christians enjoying all things deeply. As if that weren’t exciting enough for the reading public, one of the leading characters in the case was Eleanor’s 16-year-old daughter, Charlotte. Teenage girls’ wild behavior was the subject of a moral panic in 1922, and here was a real live flapper, who sported bobbed hair and short skirts. Papers described her as having “the physical and mental development and independence of convention of a grown woman.” She also had a firm opinion about the identity of the murderer, and wasn’t shy about talking to the press. “A jealous woman killed my mom and Mr. Hall,” she told reporters, before naming the suspect “with bitterness in her voice.”

The jealous woman was Hall’s wife, the former Frances Noel Stevens, an heir to the Johnson & Johnson fortune. Edward Hall had been the “handsome young rector with New York manners” whose wooing swept the rich and “high-principled spinster,” a decade his senior, off her feet. Now, the papers described Mrs. Hall as “stout and gray-haired and no longer young,” while her husband’s murdered paramour was the “young and pretty wife of the church sexton.”

Mrs. Hall refused to hire a private detective, on the grounds that to do so would “show an unchristian disposition to get vindictive revenge.” She believed the murders had been “a terrible mistake of some kind.” (This may well have been the truth. One theory of the case suggests the killings occurred when the adulterous couple was confronted by Mrs. Hall and several male relatives, and things got out of hand.) The partners of the victims steadfastly maintained their belief in the innocence of their departed spouses’ relationship, or so they said. When Mr. Mills visited Mrs. Hall in the days after the murder, she promised that she would “spend her strength and resources to find the murderer.”

Even though Mrs. Hall had been her Sunday school teacher, Charlotte had never liked her. The feeling may have been mutual. “Mrs. Hall does not like flappers, and I’m a flapper,” said Charlotte. On the other hand, she and her mother had been “chums” who for years had shared a bedroom after Eleanor stopped sleeping with her husband, James (by all accounts, Mr. Mills was an unambitious loafer). Her mother made Charlotte’s clothes and “always had a surprise for me. A handkerchief, a ribbon, a book,” she remembered in a heart-wrenching article she wrote for Cosmopolitan magazine in 1929.

Several months prior to the murders, Eleanor told her daughter that if she didn’t survive an upcoming kidney operation (paid for by the Halls), Charlotte should make sure that a bundle of incriminating letters be sent to one of Eleanor’s sisters. Charlotte also knew that her mother left letters for Hall in a particular large book in his study, one located on “the second shelf from the bottom of the bookcase.” Perhaps she also knew that her mother recently had become violently ill for days after accepting a cup of coffee from Mrs. Hall. “If I did not know Mrs. Hall was a dear friend,” Elearnor told one of Charlotte’s aunts, “I would have been sure the coffee was poisoned.”

When a distraught Charlotte went to visit Mrs. Hall after the bodies were discovered, she was met instead by one of Hall’s attorneys who suggested the teen be sent to an institution. “Why should I be put away,” Charlotte asked reporters. “Just because my mother was murdered? Just because I didn’t hesitate to say who I thought had guilty knowledge of the murder? Well, I’m not going to be sent away.” The failure in 1922 of the Grand Jury to indict anyone for the murders hadn’t changed her “opinion a bit as to the identity of one person who was certainly mixed up in the plot that resulted” in her mother’s death.

Her experiences inside the Grand Jury room convinced her that the district attorney “was much more interested in the slanderous reports concerning my own life” than he was in finding the murderer. Charlotte was appalled that, instead of being questioned about her mother’s movements and frame of mind, she had been grilled about whether she herself smoked or drank (she did neither). She also faced insinuations that she’d rather go to roadhouses at night than stay home and keep house for her father and brother.

Townsfolk criticized her for not wearing black. “Look at her!” she heard a woman say. “Wouldn’t you think she’d have the decency to wear black for her mother. That girl’s a disgrace to the town.” Charlotte later explained that her mother asked her not to wear black if she died. A Christian despite her sins, Eleanor Mills told her daughter that death was “the best thing in life.” Someone nevertheless sent Charlotte a black veil with a note that read: “Wear this veil to hide your face… It is not fit to be seen. You are a public disgrace.”

Four years later, the case reignited when the husband of the Hall’s former maid, Louise Geist, claimed in a divorce petition that she had received $5,000 for withholding crucial information from investigators. Back in 1922, Louise testified about comings and goings in the Hall household on the last evening of the reverend’s life, as well as that an upset Willie Stevens (Mrs. Hall’s “eccentric” brother who lived with the family) told her the following morning that “something terrible happened last night.” According to the divorce petition, Mr. Hall told Louise (she sarcastically called him “my old buddy”) that he and Mrs. Mills planned to elope. Louise passed this tidbit to Mrs. Hall on the night of the murder. Mrs. Hall, along with Willie, were then driven to the lovers’ trysting spot by the family chauffeur.

The explosive allegations, along with pressure from William Randolph Hearst’s Daily Mirror newspaper, resulted in Mrs. Hall, Willie Stevens, plus another brother and a cousin being charged in the deaths of Edward Hall and Eleanor Mills. Trial began on November 3, 1926.

There isn’t enough space to go in to all of the details here, but suffice it to say the Hall-Mills case is stuffed with enough gossip, intrigue, and just plain weirdness (the state’s star witness was known as the “Pig Woman,” for the hogs she raised on her farm) to satisfy the most discriminating true-crime fan. Charlotte alleged jury tampering (she saw one of the defense attorneys speaking to a jury member), as did several others, but their concerns were ignored. On December 3, Mrs. Hall and the other defendants were acquitted in what Charlotte called “a terrible miscarriage of justice.”

During the trial, Charlotte Mills was once again an object of fascination. She had lost none of her bluntness. “There was one thing about the murder which always impressed me as the act of a woman,” she told reporters. “This was the cut throat. Whoever did this was just as bad as the person who fired the bullet and ought to suffer the full penalty of the law.” Now 20 years old and working as a stenographer in New York, she “resembled a Broadway ingenue,” according to one news report. The papers carefully detailed her fashion choices, including the “large picture hat, a white and brown summer frock, flesh colored stockings and white shoes,” she wore to the courthouse on the day of her testimony.

Not all the coverage of Charlotte and her clothing was positive, however. Novelist Anne Austin called Charlotte “the swagger flapper type, a little pert, a little too sophisticated to win much sympathy, a little too adroit in making the most of the opportunities that have come to her through her dreadful notoriety.” Austin described Charlotte’s “pretty face… strong, supple young body” and “knowing but still dewy blue eyes” before taking her to task for selling her story to a newspaper syndicate. Her cute outfits were the result of blood money, Austin suggested. “And so she sold her heart and her memories of her mother and Dr. Hall to the papers. Would any of us rather see her in queer, cheap little garments, because the effect would have been more dramatic?” Now, Austin continued, it was said that Charlotte “looked toward Broadway as a market for her prettiness and peculiar fame.”

This was too unfortunately true. Beginning in December 1926, Charlotte appeared “in person at every performance” of “Who’s Guilty?,” a play based on the Hall-Mills murders. She had refused a larger role in the play, finding it “distasteful,” and instead gave a curtain speech. “My mother was a good woman. Please try to think kindly of her,” she told audiences, then recalled her mother’s final words to her: “Wait for me until I come back.” Charlotte was “pale and haggard,” by one account, “on the verge of a physical and mental breakdown.” She was denounced from pulpits and editorial pages for what was viewed as a pathetic attempt to cash in on the tragedy. The play folded after five weeks.

In fact, she needed the money. As she later explained, she was unable to keep a job, not because of her abilities or demeanor, but because once her employer or coworkers found out she was Charlotte Mills, they fired her. Little sympathy awaited her at home. When she was dismissed without explanation from a job in a New York City department store, her father told her: “Well, there’s nothing to be done about it. What else could you expect? Your mother did it. She dragged my name in the mud. If she had stayed at home and behaved herself, all this wouldn’t have happened to you. You’re her daughter, and you can’t expect people to think well of you.” Not surprisingly, Charlotte went to live with her mother’s sisters.

Charlotte’s notoriety remained strong enough in January 1927 that she was subpoenaed to appear at the divorce trial of 51-year-old real-estate magnate Edward West “Daddy” Browning and his 16-year-old child bride, Frances Heeman Browning, known far and wide as “Peaches.” Apparently, Charlotte had been in the waiting room of the Hearst newspaper syndicate while Peaches discussed her series, “Why I Left Daddy Browning,” behind closed doors. (The syndicate wrote both girls’ serialized stories, though each carried a byline making it seem like she had written the story herself.) When Charlotte appeared in court, one paper called her “that drab, troubled looking little reminder of the Hall-Mills trial.”

That same year, Hearst’s Daily Mirror hired Charlotte to write a column called the “Dog Exchange,” in which she found new homes for stray dogs. But when Hall-Mills publicity finally died down, Charlotte was no longer useful to the paper, which had only hired in her in order to keep her close in case they needed her for a story about the murders. She was fired.

Charlotte Mills died of cancer at 46 in 1952, after a life of “self-imposed anonymity.” Even so, notoriety stalked her from beyond the grave. When the adult children of a woman in Philadelphia submitted her obituary to the local newspaper in 1986, they were shocked to discover that she was not in fact, the Charlotte Mills of Hall-Mills murder fame, an identity she had been using since at least the early 1930s. When her children asked her why author William Kunstler in his 1960 book about the case had said Charlotte Mills died in 1952, their mother “just brushed it off” and told them to “Let it rest.” (Her real name was eventually found to be Marie Thompson. Perhaps unsurprisingly, friends described her as “a real lollapalooza.”)

The real Charlotte Mills never recovered from the loss of her mother. As she wrote in the 1929 Cosmopolitan article, her beloved mother was taken away overnight “and life’s all different and I know I can never go back to what it was before.” She used to be a tender-hearted girl. “Anyone’s troubles made me cry. Now I just want to laugh and laugh — perhaps because laughter is so close to tears.” Her mother’s murder remains unsolved.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.