PLANET OF PERIL (13)

By:

February 9, 2017

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

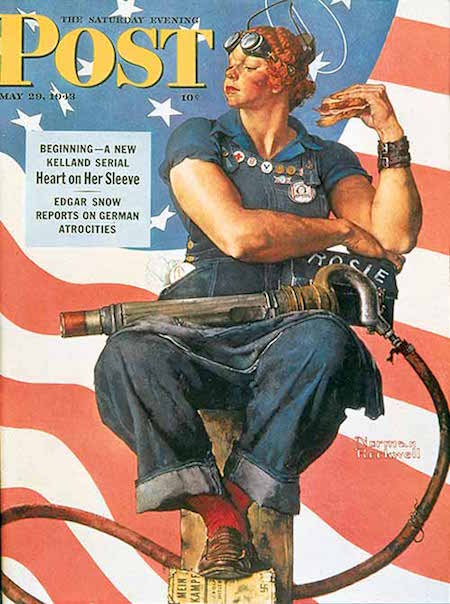

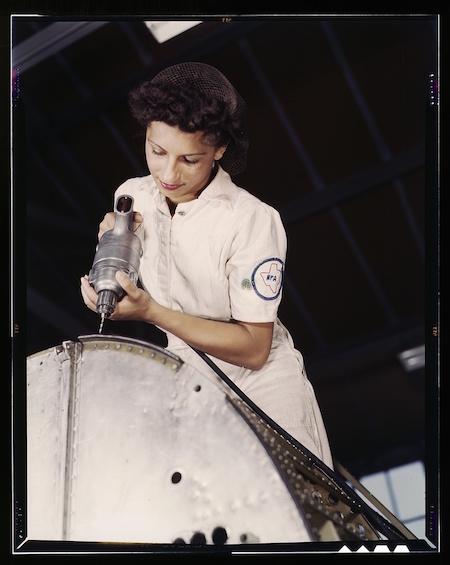

Norman Rockwell’s 1943 Saturday Evening Post cover portrait of Rosie of the Riveter has become so iconic that it’s hard to picture an American woman war worker of the period any other way than dressed in overalls with a rivet gun in her lap. To modern eyes, Rosie’s utilitarian outfit seems anything but controversial, but questions concerning the propriety of women in slacks raged for the duration of the war.

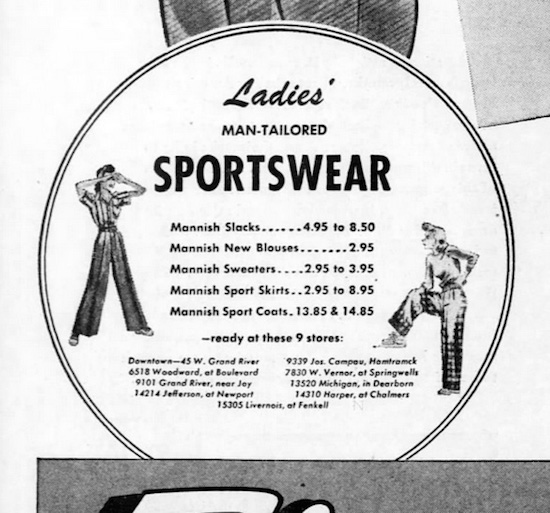

Dress reformers in the 1850s and bicyclists in the 1890s respectively experimented with Bloomers and divided skirts, but pants as women’s leisurewear really started to catch on in the years before Pearl Harbor. Interviewed in 1942, a buyer for “one of New York’s Best department stores” told a syndicated columnist that women had been “quietly wearing slacks,” for activities like housework and gardening. Since the attack, however, there had been an almost 300 percent rise in sales. Slacks were handy in case of emergency. “No girdle, no stocking — you step in, and you’re adequately and modestly clothed, and you are warm.” They were also integral for some kinds of factory work.

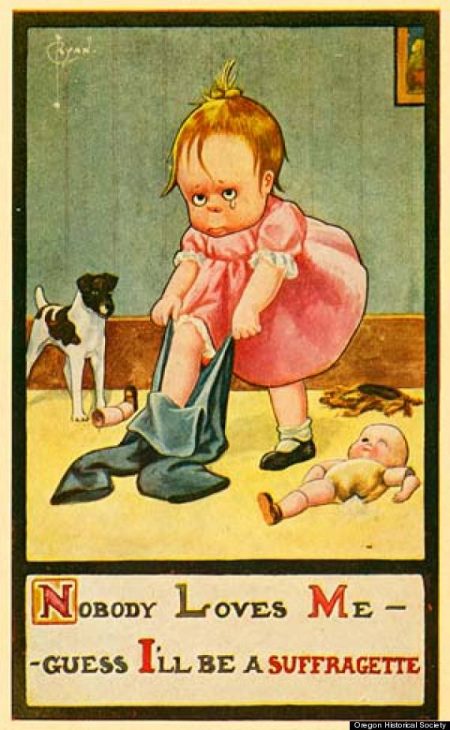

Yet the idea persisted that, in the words of an anti-suffrage postcard from 1906, “Pants are made for men, not for women. Women are made for men, not pants.” Could a woman war worker maintain her femininity while wearing menswear and doing men’s work?

Opinions varied. A writer at the Brooklyn Eagle declared herself a “One-Woman Crusade Against Slacks-Wearers Who Wear Them for No Particular Reason” in August 1942. “The hullabaloo for wearing slacks was stirred up as a direct result of increased activities for women in war time. Slacks, it was argued, allowed a woman more freedom, permitted her to do a man’s job less conspicuously than if she were attired in form-fitting sweater and skirt.” The writer conceded that slacks were appropriate for jobs in defense factories. But when it came “to a choice between a woman wearing slacks willy-nilly on all occasions and… looking like a woman in clothes that flatter her own physical attributes,” she’d take the latter.

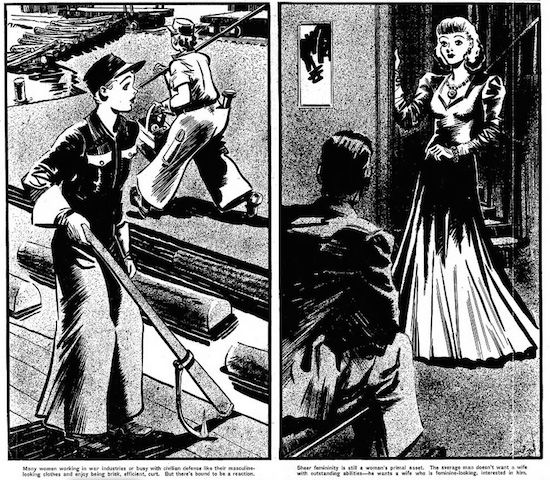

Pop psychologist Harold Johnson, whose 1943 column took up a full page in several newspapers, thought women enjoyed wearing slacks a little too much:

Strutting around in a snappy, masculine-looking uniform? Like its feel of mannishness?

Working in a defense industry? Running a canteen unit? Member of a motor corps?

You like your trim, tailored trousers or slacks! You like to be brusque, efficient, curt. In fact, ladies, you’re getting a kick out of all this business. And the more it takes you away from traditional cloistered feminine existence, the more you like it!

Once again, pants were acceptable in factories or civil defense activities, even for gardening, but trouble arose when a woman went “berserk over the new opportunities for masculine clothing and mannish actions.” If a woman wanted to interest a man (Johnson left no room for other attractions), she needed him to think of her as a “feminine creature” at all times. “Your clothes should serve as part of your appeal in feminine charm.”

Laurel Nelson Baker assumed readers of her 1943 guidebook for would-be war workers possessed this feminine concern for clothing. “There is hardly a woman who has considered going to work in a factory… who isn’t going to ask, and perhaps a little tremulously, ‘But what shall I wear?’” she wrote in Wanted: Women in the War Industry. “You must admit, for it is a well established fact, that you are a vain creature. And all the factory jobs in the country, whatever their other compensations would not appeal to you if you had to appear before your fellow workers wearing some ‘simply horrid looking thing!’”

What women actually wore to their factory jobs varied enormously. Nell Giles was a Boston Globe columnist (“Susan, Be Smooth!”) who took a war job in 1942 in order to write about it for the paper. Her coworkers at a General Electric plant in West Lynn, Massachusetts, mostly wore skirts and dresses under work smocks, including a fashionista in “black linen toe-strap sandals, pink toenails, and a black-and-pink cotton dress.” Giles thought that the women who did wear pants looked well dressed, and was surprised that slacks were “the exception and not the rule” for assembly jobs.

Ann Pendleton dressed “unglamorously in cotton blouses and blue slacks” for her factory job three hours outside New York City, an experience recounted in her lightly fictionalized Hit the Rivet, Sister (1943). Others wore similar outfits, but many worked in flowing “pajama suits… bright yellow, pale pink, gorgeously flowered.” All looked with disdain at a “college girl” who “wanders among us in her trimly tailored pastel coveralls” straight out of a fashion magazine spread. Everyone wore makeup; Pendleton was lectured by a work pal who didn’t think she touched up her lipstick often enough. When rumors circulated that women workers would be required to wear uniforms, blame was immediately placed on the factory’s so-called “sweater girls,” rather than on the male workers who shouted “Keep ‘em flying” as they passed by.

“There is sex in war plants, sure,” wrote fashion designer and all-around maverick Elizabeth Hawes in Wenches with Wrenches (1943). “But it’s absolutely no problem to anyone. If you want it, you can have it — and if you don’t want it, nobody bothers you.” (She and the women she trained with were subjected to another kind of harassment, however, “admonished by one instructor that women have no place in a machine shop” while another “busied himself persuading the females they would lose their femininity if they wore slacks.”)

Hawes was a tough cookie, but other women clearly were bothered by the attention they received. Women war workers were better off “unpainted and unvarnished” and dressed in work clothes due to “the simple and undeniable fact that there would be nothing left of us, pants or no pants, if we really looked as we like to think we do in our civilian clothes,” wrote Josephine von Miklos in I Took a War Job (1943). A former New York photographer and industrial designer, Von Miklos worked as a drill press operator in a New England plant making bombs and fuses. She later transferred to a shipyard, where she found a “legion of waterfront Casanovas… just like schoolboys who think that bathroom jokes make them sound grownup.”

Slacks were supposedly “unfeminine,” yet they didn’t actually protect women from unwanted attention. Constance Bowman and Clara Marie Allen were schoolteachers who spent a summer building B-24 Liberator bombers, then wrote about it in Slacks and Callouses (1944). They found “just two kinds of women” in wartime San Diego: those who went to work in skirts and those who went in slacks. Far worse than the female ice cream clerk who refused to serve them because they wore Consolidated Aircraft uniforms were the men “lounging on corners” who looked them over from head to toe “in a way we didn’t like… with special focus on the ‘empennage’ (a term for the tail assembly of an airplane…). Men grabbed us and followed us and whistled at us.” (A pickup line noted by more than one memoirist: “How about a little war work?”)

Clothes, they “reflected sadly, make the woman — and some clothes make the man think that he can make the woman. In our dusty blue slacks we were ‘Sister’ and ‘Baby’; and even our glasses, Dorothy Parker to the contrary notwithstanding, were no protection.”

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.