PLANET OF PERIL (38)

By:

April 13, 2019

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

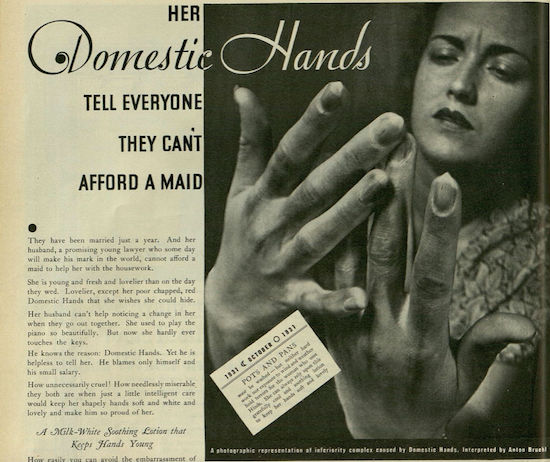

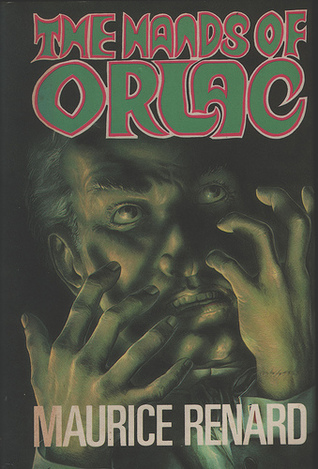

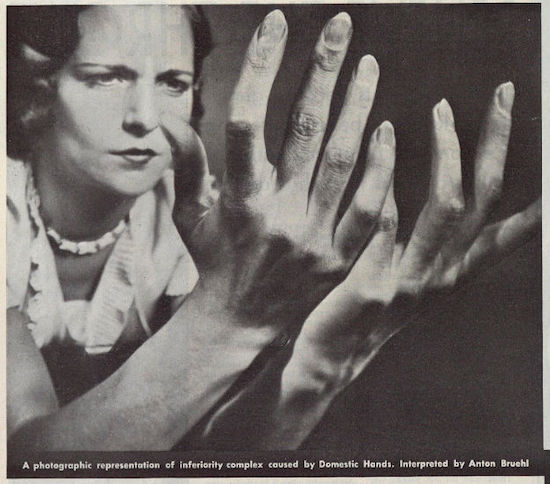

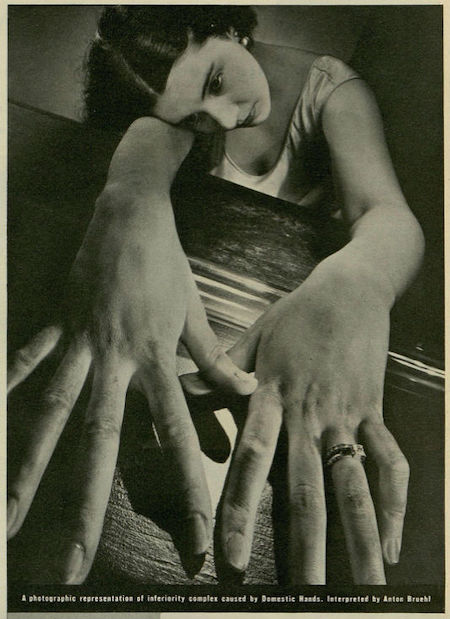

Even by the fear-mongering standards of the beauty industrial complex, the six ads that appeared in women’s magazines in 1931 and 1932 were doozies. Each was illustrated with a different photo of a woman with ludicrously outsized hands, described by a helpful caption as a “representation of inferiority complex caused by Domestic Hands.” This was a malady that could only be cured by the liberal application of Hinds Honey and Almond Cream hand lotion. The high-contrast black and white photos (credited to commercial and fashion photographer Anton Bruehl) featured the odd angles and dramatic shadows au courant in German Expressionism and film noir. A friend points out the similarity between the photos and images from the 1924 version of The Hands of Orlac, an Austrian silent film about a pianist who loses his hands in an accident, only to receive the hands of a murderer in a transplant — hands that are no good at playing the piano any more, but may still be good at killing.

Other companies used the phrase “inferiority complex” in their advertising. Lux soap flakes, for example, used the face and name of famous advice columnist Dorothy Dix in a 1931 ad that suggested no woman need feel inferior if only she washed her lingerie in Lux. But the ad was bright, colorful, and ultimately hopeful. Like many other fear-based ads, it identified a problem (possibly nonexistent outside the world of advertising), added a sprinkling of social anxiety, then promoted the product as a solution. It was unclear whether the women in the Domestic Hands ads ever fully recovered, or whether they obsessed over their now soft and smooth hands from the confines of a rubber room.

The lotion had been around since the nineteenth century, when druggist A.S. Hinds of Portland, Maine, decided to concentrate his business on his most popular product. He invested in nationwide advertising, none of which featured the doom and gloom of the 1930s campaign. Ads from the late 1880s or so described Hinds Honey and Almond Cream as an all-in-one product that could be used on “chapped hands, face, and lips” and made “an excellent lotion for gentlemen after shaving.” In the 1910s, the company offered “The Hinds Cream Girl Calendar” for 10 cents postage paid or free with purchase of a 50 cent bottle. The full-color poster (“with no advertising on front”) featured three photos of a beaming young woman. If that wasn’t exciting enough, the cream was “positively guaranteed not to grow hair,” the copy noted with emphasis.

Then, in 1925, A.S. Hinds sold the company to Lehn and Fink. The new owners of Hinds Honey and Almond Cream were old hands at scare tactics when it came to advertising one of their marquee products, Lysol. “She lacked poise,” was the headline of one 1923 ad. “You might have said ‘she was self-conscious,’” the text continued, but the real problem was feminine hygiene. Nothing that a soothing Lysol-and-water douche couldn’t cure!

Self-consciousness, aka “inferiority complex,” was also key to the Domestic Hands campaign. The first ad appeared in 1931. A disturbed-looking woman stared at her enormous mitts, and a headline proclaimed: “Her Domestic Hands Tell Everyone They Can’t Afford a Maid.” They had only been married a year. He was “a promising young lawyer” who would someday “make his mark in the world,” but didn’t earn enough yet to hire household help. She was “lovelier than on the day they were wed,” except for her chapped hands. Her husband noticed a change in her demeanor. She used to play the piano, but “now she hardly ever touches the keys.” Hubby knew “the reason: Domestic Hands. Yet he is helpless to tell her. He blames only himself and his small salary.” The copy hurtled into overdrive: “How unnecessarily cruel! How needlessly miserable they both are when just a little intelligent care” would keep her hands soft and lovely, and the two of them presumably happy.

The following month, another ad appeared. This time, a worried blonde contemplated her outsized paws under the headline: “He Thought Her Lovely As a Fairy Princess Until He Saw Her Domestic Hands.” Then came an ad that showed a blowsy woman dressed in what looked like a slip playing cards. “Like Dirty Fingernails Domestic Hands Make Women Self-Conscious,” the text explained.

These were nothing compared to what came next. “Her poor bewildered husband simply can’t understand the change that has come over Helen since her marriage last June,” read an ad from early 1932 (one might have thought it was “their” marriage). Helen used to love to socialize but now she never wanted to go anywhere. And forget having guests over. “It was actually embarrassing the other night when Tom brought Ted Graham home for dinner without warning. And after he had gone there was another of those awful weepy scenes.” The problem was not Tom’s inability to call ahead and let his wife know that the insufferable Ted Graham would be joining them for dinner, but “of course, a bad case of Domestic Hands.”

And then there was “The Tragedy of Nan,” a dark-haired, dark-eyed newlywed who stared sadly at those damned gigantic hands of hers. Her marriage to John had been “a real love match, even if it “meant sacrificing luxuries she had taken for granted all her life… doing without a car, going without a maid.” After “a brief honeymoon,” Nan had “plunged into the mystery of housekeeping” as if it were “a gay adventure.” She had “abiding faith in John’s cleverness. He was bound to succeed. It thrilled her to think that she was playing an important part in his success.” You already know what happened next. The “vivacious, carefree” Nan disappeared, replaced by a “furtive, self-conscious, shy” stranger who “even showed her resentment when John brought guests home to dinner.” The ads featuring Helen and Nan suggested that something mysterious and damaging happened to women after the wedding. A similar theme ran through advertising for feminine hygiene but here the danger to marriage and mental health wasn’t sex but improper post-housework hand care.

In addition to the class issues on display (don’t let your hands tell people you can’t afford a maid!), the Domestic Hands campaign had racial overtones. Hinds Honey and Almond Cream was a “milk-white lotion” that promised to impart the same shade to the user’s hands. All one had to do was smooth it on “two or three times a day” and the “most chapped and neglected hands” would grow “softer and whiter and more attractive.”

Smooth, white hands were a longstanding mark of wealth and leisure. In both book and film versions of Gone with the Wind (1936 and 1939, respectively), former belle Scarlett O’Hara is newly poverty-stricken in the wake of the Confederacy’s loss, and must tend to the cotton fields without the assistance of slave labor. In a famous scene, she makes a gown of her plantation’s curtains, then goes to beg scalawag Rhett Butler for money. Butler is momentarily taken in by her display of prewar grandeur, then sees and feels her callused hands. “These don’t belong to a lady. You’ve been working like a field hand,” says Clark Gable’s movie Rhett, in a sanitized version of the book’s language. Book or film, the racial component is clear. Ladies’ hands are white, not only because others do the work, but because “ladies” are by definition Caucasian. Similarly, had the young white housewives in the Domestic Hands ads been able to hire maids, they would in all likelihood have been women of color.

The final ad in the series appeared in April 1932. A woman reached skyward, while the text implored: “Don’t reach for the rainbow with (chapped) Domestic Hands.” Home, hearth, and happiness all depended on one’s hands. It was simple: “roving eyes” went first to a woman’s extremities. Unless her hands were “white and soft and lovely, they may give the wrong impression.” Only a few months later, the December 1932 installment of “The Beauty Clinic,” a regular feature in Good Housekeeping magazine, asked: “Have you a little inferiority complex which takes the joy out of life for you?” Columnist Ruth Murrin suggested those who did look carefully in their mirrors. She was “convinced that many of you who write me are making a mountain out of a molehill.”

Hinds Honey and Almond Cream remained on store shelves for at least another couple of decades, but its advertising never again reached the film noir heights of the Domestic Hands campaign. A series of ads from 1949 focused on outsized, disembodied hands, but now the lighting was softer. The hands were ogled by men (engagement rings conspicuously on display) or groomed cherubic babies. Domestic hands had been domesticized.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.