PLANET OF PERIL (36)

By:

February 12, 2019

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

“Scarcely a day passes that some mother does not appeal to us to exert whatever influence is in our power against the jazz tendency of the day,” wrote the editor of the Ladies Home Journal in the fall of 1921. What could be done with “a flapper daughter who drinks whisky, smokes cigarettes, wears diaphanous, clinging frocks, parks her corsets at dances, and rolls her stockings below the knee”? The “jazz type” of young woman “substituted the brazenness of the harlot for the dignity and naturalness and sweetness” of the old-fashioned girl. Articles with titles like “Does Jazz Put the Sin in Syncopation” (short answer: yes) and “Unspeakable Jazz Must Go!” made the Journal’s position clear: America was “dancing hellward, via the jazz route,” and young women were leading the way.

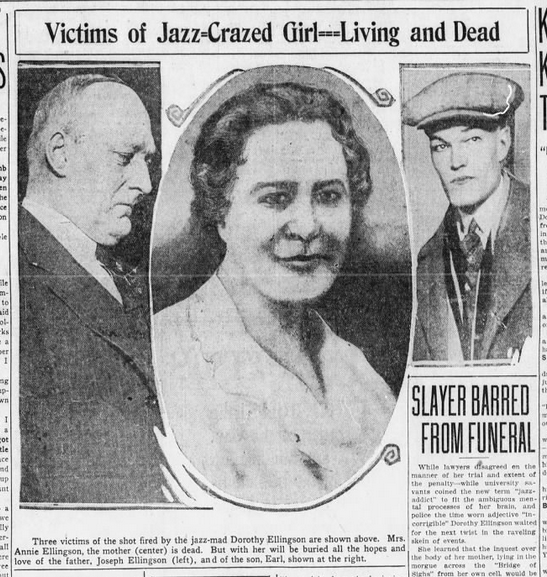

Yet even the most stalwart of the Journal’s moral crusaders could not have foreseen the public uproar that occurred in January 1925, when 16-year-old Dorothy Ellingson of San Francisco shot and killed her 47-year-old mother, Anna. “Dorothy wanted powder and rouge and lipstick,” her shocked and heartbroken brother, Earl, told reporters. “She wanted bobbed hair and fancy clothes. She was full of life, overflowing with enthusiasm and ‘pep.’” Dorothy wanted to stay out all night long, dancing to that most modern music, jazz, at Chinatown clubs. She had fallen in with a group of musicians, and often didn’t come home until the wee small hours of the morning. Her night owl lifestyle made it difficult to hold on to her work as a stenographer. The new year was supposed to be a new beginning, and when Dorothy told Anna she was going to a party that night, they quarreled. Again. Only this time, Dorothy grabbed Earl’s revolver from a drawer and shot her mother dead. Then she rifled through Anna’s purse, and left the house. That night, Dorothy went to the party, where she drank, laughed, and acted as if nothing out of the ordinary had occurred.

The press, especially William Randolph Hearst’s sensationalistic San Francisco Examiner, went berserk. “The human story” behind the murder, wrote a columnist for Hearst’s paper the day after the killing, centered on “a beautiful girl, a mere child, the butterfly daughter of an old-fashioned mother” who didn’t understand “modern things.” Dorothy was “fiery haired, tall, slim, gay” and was only “answering the call of life,” according to the Examiner’s columnist. The “cafes, cabarets, hotels, rooming houses” that police searched when looking for her were “the places butterflies may go to get their wings singed.”

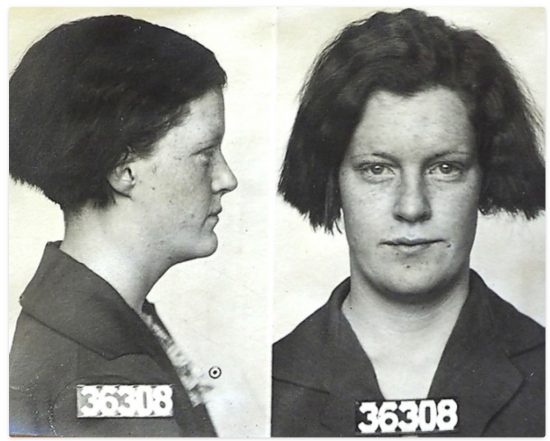

As the lurid details of Dorothy’s crime and past behavior became known, she quickly dropped in the press’s estimation from a butterfly to a moth — and not “a bright gay moth, but a besmirched little thing with drooping wings,” according to another Examiner columnist. She was “not a beauty,” despite what other reporters said. She had “a mop of reddish hair, not any too well kept, rather good features, a pair of sly eyes, shallow and deceitful, a secretive smile… a constant, never-ending, never-changing smile… full of cunning and full of guile and full of the strange, secretive pride of her strange, secretive heart.”

“Tiger Girl.” “Jazzmaniac.” “Moth Girl.” The press couldn’t get enough of “flame-haired” Dorothy and her sordid story. She ran away from home the first time at age 12, played hooky from school for weeks at a time (but was intelligent enough to keep up with her class). At the time of the murder, she was a ward of the juvenile court. At the Coroner’s inquest, her father and brother testified that Dorothy had “a willful disposition and for the last four years had been virtually incorrigible.” (According to the New York Times, the “jury further went on record as favoring enactment of legislation regulating the sale and possession of firearms,” as without access to her brother’s .45, Dorothy surely would not have shot and killed her mother.)

As evidence of her incorrigibility, the papers pointed to her diary, part of which was written in a kind of shorthand code. Much of what could be deciphered was “unprintable: ribald verse, toasts, jingles.” Whatever could be printed, was. Even viewed from a much more permissive era, there was enough to worry any parent:

“Met H. and had a fine feed. Nice fellows. This is the life, wonderful time. Pep, jazz, gin. Went to the beach and later got drunk.”

“Out on a hot-time party with Ben and the gang. When it was all over I was all in.”

“Another whipping, but I stayed home. Won’t stand for another one. Will do as I please henceforth and love where I please. Tuesday another auto ride and lots of drinks. Big time. Lots of love, too.”

A reporter enumerated the things that Dorothy loved and understood: “Jazz, automobiles, the moving pictures, chop suey restaurants, the snarling whine of the saxophone, the teasing wail of violin strings, bright lights, loud laughter.” It was a litany of everything the Ladies Home Journal found unwholesome and indecent.

Another reporter was more succinct: “This is a tale of the jazz age.”

Across the Atlantic, one of the architects of the jazz age took notice. F. Scott Fitzgerald, trying to write a new novel in Paris, followed the Ellingson murder in the international edition of the New York Herald Tribune. He tried to work it and the Leopold-Loeb case of the previous year (in which a pair of privileged teens kidnapped and killed 14-year-old Bobby Franks in what they planned as, but turned out not to be, the “perfect murder”) into the story. He said as much to his agent, as well as to his frenemy, Ernest Hemingway. The heroine of his work-in-progress, he confessed to Hemingway in a mostly tongue-in-cheek 1926 letter was “a girl named Sophie Irene Loeb who kills her mother.”

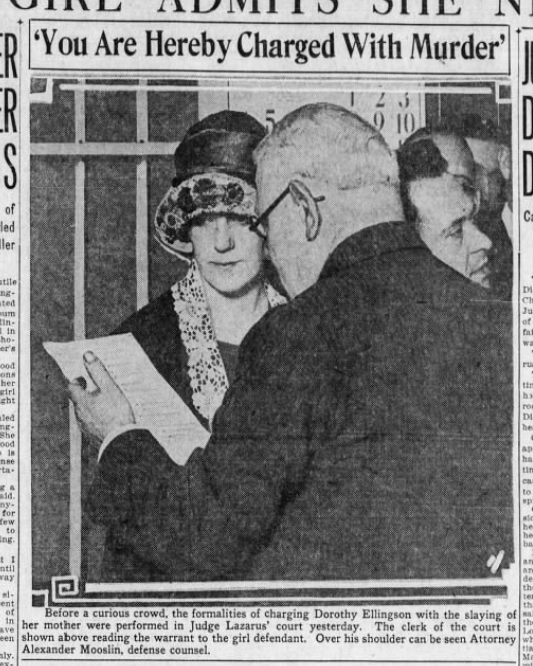

Police said that Dorothy wept broken-heartedly in her cell, but her behavior in court did little to change the public’s perception of her as a cold and calculating “matricide,” as the papers called her, willful and lacking in self control. During a days-long proceeding to determine her sanity (ordered by the judge after she fainted in court one too many times), Dorothy “hurled” a glass of water at her attorneys, and smashed a bottle of smelling salts on the table for emphasis. “I wish I could take the stand and tell the truth,” she cried another day. “Anybody could get up and tell those lies about me. You’d better get out of my sight before I choke you.”

The jury found her insane. Juror Marie Dietz based her verdict on the fact that Dorothy went out to the party “where she danced, drank whiskey, and did other worse things only a few hours after the crime.” Only a crazy girl could murder her mother, then “make love, drink liquor, dance, and laugh” like nothing happened, in Mrs. Dietz’s opinion.

As for Dorothy’s fainting in court, Dietz was wise to that. “I am a woman and know most of the tricks of my sex.” It was easy to bring on a faint: “Just breathe deeply, do everything to work your nerves to a high pitch, and then, at the right moment, hold your breath. If you know the trick you will faint like Dorothy Ellingson did every time in court.” Dorothy’s pale complexion was as fake as her fainting. “No woman could possibly be as pale as she appeared in court. She may have ‘taken in’ the men, but not me.” Mrs. Dietz saw traces of cold cream and “powder in wholesale lots.”

Thirty days after she was remanded to the insane asylum at Napa, Dorothy was examined by a panel of eight doctors who agreed she was never insane in the first place. What she lacked was “the right parental influence.” It was “very evident,” in the opinion of one of them, that “her parents did not give her the necessary moral training to develop within her resistance to wrongdoing.”

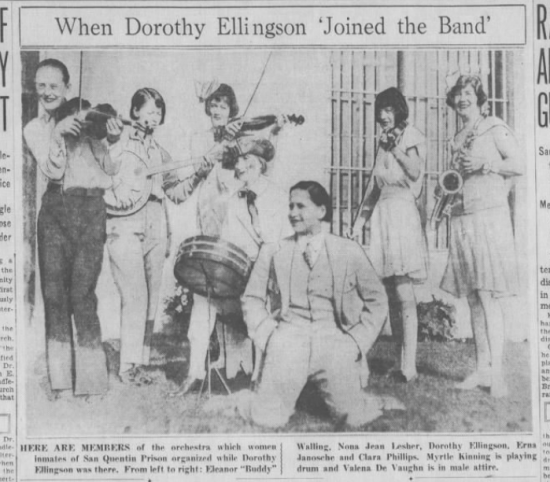

This time, the trial proceeded without interruption. Dorothy, now 17 years old, was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to from one to ten years in San Quentin. (The penitentiary held both male and female inmates until 1932, when the California Institution for Women was opened at Tehachapi.)

She served six and a half years. “There is no ‘next job’ of crime for me,” she wrote (or “wrote”) in a series for the Examiner about her life in prison, after her release. “If the world will give me half a chance, Dorothy Ellingson will become a good citizen. That is my promise.”

Almost exactly a year later, in March 1933, Dorothy was arrested in San Francisco for grand theft after she stole jewelry and a black velvet dress from her roommate. “I must have been crazy to take those things,” she told the inevitable herd of reporters. “No, please don’t say I wanted the dress to go to a party.” Out on bail, she was hospitalized after a serious suicide attempt. The roommate (who was unaware that her flatmate “Dorothy Jentoff” was the famous killer and disturbed by her suicide attempt) refused to press charges, and a judge dismissed the case.

Dorothy had at least a couple more brushes with the law. In 1938, a young woman being held on a morals charge slipped out the door of SFPD’s Northern Station, and left in an automobile with “jazz girl” Dorothy Ellingson. Dorothy’s notoriety ensured she made the papers, but she was not charged with any crime.

The situation in January 1955 was altogether more serious and sad. Newspapers reported that 46-year-old “faded beauty” Dorothy, and her 16-year-old son were jailed in facing cells in Marin, she for grand theft ($2000 in jewelry, clothing, and cash from a former employer), he for burglary (he broke into a house on Christmas Eve). Dorothy told reporters that her son “took it like a little man” when she told him, as they both sat in jail, that she had killed her mother all those years before (the local paper also noted that Dorothy “attempted to throw the blame on her 16-year-old son” when confronted by police with the stolen goods). Estranged from her construction worker husband, Dorothy (living under the name Diane Stafford) said she stole the items because she needed money help her 17-year-old daughter, who was married with a child of her own. Dorothy was sentenced to six months in county jail.

Fitzgerald was long in the grave by then, of course, felled by heart attack at the age of 44 in 1940. Tender is the Night was published in book form in 1934. Fitzgerald jettisoned the matricide storyline after six drafts.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.