PLANET OF PERIL (40)

By:

July 14, 2019

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

Moscow-based American journalist Edmund Stevens got the scoop on Valentina Tereshkova, not long after she became the first woman in space in 1963. “I wondered what sort of girl she was,” he mused in an article for Ladies Home Journal titled “Comely Cosmonaut.” The American press had described her as “mannish” or as a “chunky Ingrid Bergman.” In fact, Stevens found Tereshkova “decidedly feminine,” neither slim nor plump, with “all of the seductive curves of an attractive woman.” There “was nothing frumpy about her attire, either,” which exhibited “quiet good taste.”

After his thorough inventory of her appearance, Stevens followed up with a few paragraphs on how Tereshkova became the first “girl cosmonaut” (a member of the local aeroclub, she had made over 160 parachute jumps, and applied for the space program in 1962), then turned back to feminine pursuits. “Whoever Valentina eventually marries will probably be getting a very competent housewife,” Stevens concluded. Before she left home for the space program, she did “the cleaning, marketing and mending” for her mother, elder sister, and brother. She was, she told Stevens, “a very good plain cook. No frills,” just the kind of food workers liked, borscht and blini, “and my strawberry jam is second to none.” (Tereshkova’s attitude towards her interviewer and his questions may be divined from her response to an inquiry about how she ate in space. Was it difficult to swallow in zero gravity? “No problem,” she told Stevens, it was just like on Earth. “Try it yourself sometime.”)

Stevens’s concentration on Tereshkova’s feminine assets and abilities was no fluke. Women scientists were viewed with skepticism by the midcentury American public, as were women doctors, lawyers, and any others who performed what was considered traditionally “man’s work.” A woman working in a man’s field was suspected of being overly masculine to one degree or another, and the press and other media tended to double-down on her traditionally feminine qualities if they wanted the public to accept her. (The same could be said for men working as teachers, nurses, or secretaries.) Hence, an article about a woman chemist that appeared in American Girl magazine around the same time made sure to let its young readers know that she also thought cake-baking was “lots of fun!”

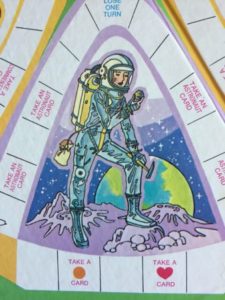

Similarly, when a revised 1976 edition of What Shall I Be? The Exciting Career Game for Girls swapped out “Airline Hostess” for “Astronaut,” the illustrations on the box cover and game board showed a decidedly pretty scientist, one who wouldn’t be out of place in an ad for Clairol’s Herbal Essence Shampoo. Her helmet couldn’t hide her blond hair, lipstick, and eyeshadow. (Sadly, the “Personality” cards are missing from my game, so it’s impossible to know if the heart-shaped card reading “You are overweight. BAD for Airline Hostess, Ballet Dancer, and Model” was retooled for the new version.)

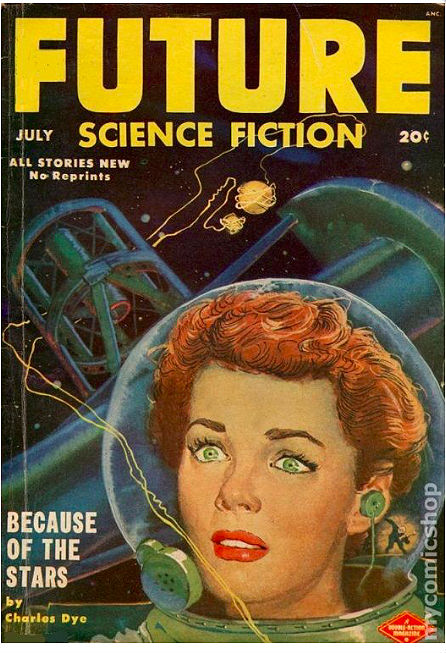

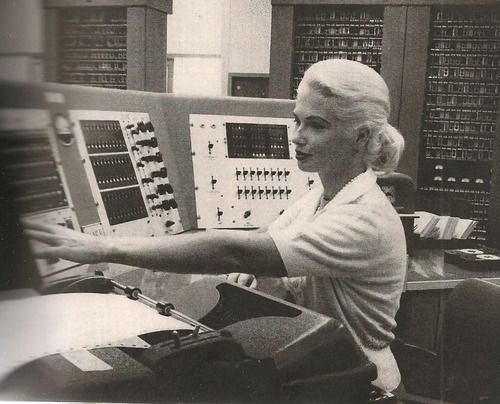

Of course, sexy alien babes and perfectly coiffed and made-up female space explorers long had been staples of American pulp magazine and book covers. Yet when Helen Mann, a flesh-and-blood “Cape Canaveral missile maid with a master’s degree,” appeared on the game show What’s My Line in 1959, the panelists were stumped. As syndicated columnist Ed Koterba put it, “who had ever seen a scientist in a tight-fitting cocktail dress before?”

Mann was a mathematical analyst who worked as a missile tracker for RCA, but Koterba barely touched on her profession in an interview that took place not long after her television appearance. Mann looked “more like a model than a lady just off the launching pad. This gal is 5 feet 5, 27, and smiles softly from a heart-shaped face that melts into long flowing locks of platinum,” drooled Koterba. “Her big, wide sky-blue eyes are just a touch softer than the sky blue jersey that wraps itself comfortably about her. This girl’s a scientist?” Koterba predicted that if Mann and women like her were “called up… for space flight training,” the “waiting line of male recruits would reach to the moon.”

Mann wanted to be “a lady astronaut” someday. When it came to explaining why women belonged in space, she used the language of traditional femininity. Women had “more patience” than men, “and a person needs a lot of patience in space science research,” she told Koterba. Patience probably helped with male journalists, too.

Pioneer aviator Ruth Nichols was one of the women who underwent the same physical and psychological testing as NASA’s Mercury astronauts at William Randolph Lovelace’s privately funded Women in Space Program. Nichols didn’t pass all the Phase I tests and thus did not become a member of the so-called “Mercury 13” (a term that historian Margaret Weitekamp finds “ahistorical and misleading”). She nevertheless called on NASA to “immediately” start a woman’s astronaut testing program. “Nature equipped us women emotionally, physically, and psychologically for space flight,” she wrote in a 1959 article about her experiences. Most women were “passive. Submissive. Patient by birthright.” These stereotypical qualities, along with the experience of childbirth (she herself was childless), made women ideal space travelers, able to face both crisis and boredom on a long flight to another planet.

Nichols stated flat out that she was “not a feminist,” but even that wasn’t enough for Mrs. Walter Ferguson, whose column, “A Woman’s View,” ran in The Pittsburgh Press. “COME now! Feminine independence shouldn’t be carried too far,” she wrote in answer to Nichols, who she deemed a “too-ardent defender champion of her sex.” Nature may have equipped women “with many strong qualities,” Ferguson conceded, “but she also provided us with tongues. And our favorite exercise is wagging them.” A long space trip “that would forbid talking would be hell for the ladies.”

For the time being, women’s space travel was a moot point. “There is no such things [sic] as a lady astronaut,” explained a NASA spokesman in 1963. “We have no plans for lady astronauts for the foreseeable future.” The spokesman then mentioned something of a catch-22: “Our requirement is for an engineering flight test pilot. … There are no girls who meet the criteria today.” Women couldn’t meet the criteria; they were excluded from consideration as jet test pilots. Writing in Ladies Home Journal in 1971, science writer Isaac Asimov was blunt. The only reason qualified American women weren’t allowed to train as astronauts was “that women are not wanted in the U.S. space program. Period.”

Did the hardcore female aviators who passed one or more phases of NASA physiological testing in Lovelace’s Women in Space Program understand his vision of the future? According to historian Weitekamp, Lovelace envisioned “a large orbiting space station with dozens of people” stationed there. Women would be needed as “secretaries, telephone operators, lab assistants, nurses,” the same traditional “women’s careers” they held on military bases back on Earth.

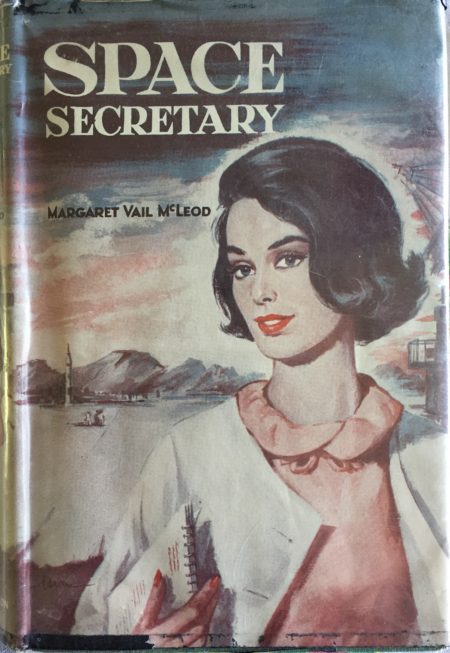

The young women who read Margaret Vail McLeod’s Space Secretary (1963) understood all too well what career paths were open to them. “I know girls can’t be astronauts,” says protagonist Carol McCann, “but Dad, don’t you believe that good craftsmanship behind a desk can be just as important to our space program as the drawing board or electronics?” Carol meets Edith on their way to Cape Canaveral’s hiring office, and worries that “the other girl was one of those mathematical geniuses who worked at Patrick [Air Force Base], the ones featured in the Sunday feature-story magazines as translating into usable data the information the missiles sent back.” But Edith is only another secretarial candidate; she and Carol work on the “Mighty Atlas” missile project right up until Carol gets engaged to the handsome blonde air force lieutenant she meets on her first day on the job. Books like Space Secretary, Space Nurse (1962) and Lab Secretary (1964) let their readers explore the few careers in science that were readily available to them.

In his 1971 Ladies Home Journal article, Asimov positioned himself as an ally to women in space, but the further one read, the clearer it became that he envisioned them as a kind of sexual support staff. He picked apart many of the stereotypical reasons why women would make bad astronauts (they were emotionally unstable during their periods, for example), then speculated on the kind of hijinks a heterosexual crew might get up to on a two-year mission to Mars. “Will the possibility of sex on board offend American morality? Is there the thought that a crew made up of … three men and three women might engage in ‘orgies’?” Asimov declared he had “no intent of arguing here that women’s role in space is entirely that of sexual partner and surrogate mother for men who do the real work.” Women, he continued, indulging in a few old canards, were “more dexterous” than men, not to mention smaller and “more resistant to stress.” Maybe they would be the “prime workers” and male astronauts would be “sent for the comfort women would derive from their company.” (The dexterity argument was usually trotted out as a reason why women made better typists, but, as Gloria Steinem pointed out, was rarely used to explain why they might make better brain surgeons — or astronauts.) Maybe celibacy was the way to go, but if not “then when do we plan to begin training women for tasks in space?” Women were “interestingly different from men in some important physiological ways,” as well. What would be the effect of low gravity “on the extraordinarily complicated reproductive mechanism of the female body”? Asimov didn’t mention whether NASA was tracking the effects of space on male reproductive systems.

NASA finally accepted six women into its astronaut class of 1978, among them Sally Ride. Five years later, Ride became the first American woman in space. Newspapers scoffed at the “unbridled sexism” in press coverage of Tereshkova’s groundbreaking flight back in 1963 — but not everything had changed. Ride, whose 27-year relationship with her female partner was disclosed only after Ride’s death in 2012, came in for her own share of sexist coverage. “There is no doubt that Sally Ride, brown hair, blue eyes, five feet five, weighing 115 pounds, is an unusual woman. … But last summer, on July 24, she did something any woman can appreciate: she got married,” explained a Florida newspaper in 1983.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.