Air Bridge (2)

By:

February 11, 2015

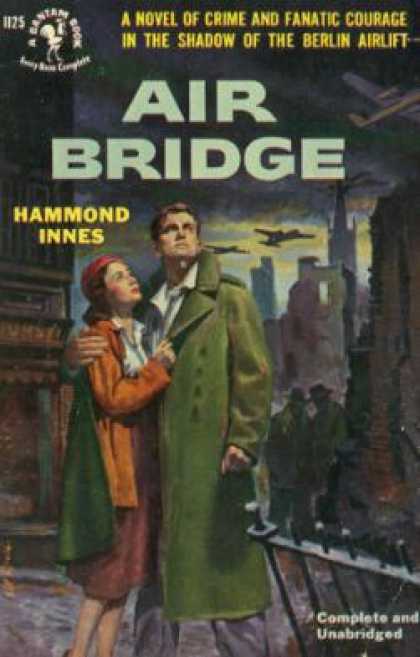

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Hammond Innes’s 1951 espionage thriller/Robinsonade Air Bridge. Set in England during the Berlin blockade and airlift of 1948–49 (during which time the British RAF and other aircrews frustrated the Soviet Union’s attempt to gain practical control of that city), the novel’s protagonist is a mercenary pilot… but is he a traitor? Hammond Innes wrote over 30 adventures, many of them set in hostile natural environments. Enjoy!

“When you’ve finished we’ll go up to the hangar.” He lit a cigarette and turned to the inside of the paper. He didn’t look up as he spoke.

I hurried through the rest of the meal, and as soon as I’d finished he got up. “Put your jacket on,” he said. “I’ll get your shoes.”

The air struck quite warm for November as we went out into the sunlight but there was a dank autumnal smell of rotting vegetation. A berberis gleamed red against the gold of the trees and there were some rose bushes half-covered with the dead stalks of bindweed. It had been a little garden, but now the wild had moved in.

We crossed the garden and entered a path, leading through the woods. It was cold and damp amongst the trees though the trunks of the silver birch saplings were dappled with sunlight. The wood thinned and we came out on the edge of the airfield. The sky was crystal clear, bright blue with patches of cumulus. The sun shone white on the exposed chalk of a dispersal point. Far away, beyond the vast curve of the airfield, a line of hills showed the rounded brown of downland grass. The place was derelict with disuse — the concrete of the runways cracked and sprouting weeds, the buildings that dotted the woods half-demolished into rubble, the field itself all plowed up for crops. Only the hangar, fifty yards away to our left, seemed solid and real.

“What’s the name of this airfield?” I asked Saeton.

“Membury.”

“What are you doing living up here on your own?”

He didn’t answer and we continued in silence. We turned the corner of the hangar and walked to the center of the main doors. Saeton took out a bunch of keys and unlocked the wicket door that I’d pushed open the previous night. Inside, the musty smell of concrete and the damp chill was familiar. Both the inboard engines of the plane were missing. It had a sort of toothless grin. Saeton pressed his hand against the door till the lock clicked and then led the way to the back of the hangar where the workbench stretched along the wall. “Sit down,” he said, indicating a stool. He drew up another with his foot and sat down facing me. “Now then—” He took my wallet from his pocket and spread the contents on the oil-black wood of the bench. “Your name is Neil Leyden Fraser and you’re a pilot. Correct?”

I nodded.

He picked up my passport. “Born at Stirling in 1915, height five-eleven, eyes brown, hair brown. Picture quite flattering compared with what you look like at the moment.” He flicked through the pages. “Back and forth from the Continent quite a bit.” He looked up at me quickly. “Have you taken many planes out of the country?”

I hesitated. But there was no point in denying the thing.

“Three,” I said.

“I see.” His eyes didn’t move from my face. “And why exactly did you engage in this somewhat risky business?”

“Look,” I said, “if you want to get me under cross-examination hand me over to the police. Why haven’t you done so already? Do you mind answering me that?”

“No. I’m quite prepared to tell you why — in a moment. But until I have the answer to the question I’ve just asked I can’t finally make up my mind whether to hand you over or not.” He leaned forward then and tapped my knee. “Better tell me the whole thing. I’m the one person, outside of the organizers of your little racket, who knows that you’re the pilot calling himself ‘Callahan.’ Am I right?”

There was nothing I could say. I just nodded.

“All right then. Either I can give you up or I can stay quiet. That places me in the position of judge. Now, why did you get mixed up in this business?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “Why the hell does anyone get mixed up in something illegal? I didn’t know it was illegal. It wasn’t at first anyway. I was just engaged to pilot a director of a British firm of exporters. His business took him all over Western Europe and the Mediterranean. He was a Jew. Then they asked me to ferry a plane out. They said it was being exported to a country where the British weren’t very popular and suggested that for the trip I use a name that was more international. I agreed and on arrival in Paris I was given papers showing my name as ‘Callahan.’”

“It was a French plane?”

“Yes. I took it to Haifa.”

“But why did you get mixed up with these people in the first place?”

“Why the hell do you imagine?” I demanded angrily. “You know what it was like after the war. There were hundreds of pilots looking around for jobs. I finished as a Wing Co. I went and saw my old employers, a shipbuilding yard on the Clyde. They offered me a £2 rise — £6 10s. a week. I threw their offer back in their faces and walked out. I was just about on my uppers when this flying job was offered to me. I jumped at it. So would you. So would any pilot who hadn’t been in the air for nearly a year.”

He nodded his head slowly. “I thought it’d be something like that. Are you married?”

“No.”

“Engaged?”

“No.”

“Any close relatives who might start making inquiries if Neil Fraser disappeared for a while?”

“I don’t think so,” I answered. “My mother’s dead. My father remarried and I’m a bit out of touch with him. Why?”

“What about friends?”

“They just expect me when they see me. What exactly are you driving at?”

He turned to the bench and stared for a while at the contents of my wallet as though trying to make up his mind. At length he picked up one of the dog-eared and faded photographs I kept in the case. “This is what interested me,” he said slowly. “In fact, it’s the reason I didn’t ring the police last night and denied that I’d seen anything of you when they came this morning. Picture of you with Waaf girlfriend. On the back it’s got — September, 1940: Self and June outside our old home after taking a post-blitz cure.” He held it out to me and for the first time since I’d met him there was a twinkle in his eyes. “You look pretty tipsy, the pair of you.”

“Yes,” I said. “We were tight. The whole place collapsed with, us in it. We were lucky to get out alive.”

“So I guessed. It was the ruins that interested me. Your old home was a maintenance hangar, wasn’t, it?”

“Yes. Kenley Airdrome. A low-flying daylight raid — it pretty well blew the place to bits. Why?”

“I figured that if you could describe a maintenance hangar as your home in 1940 you probably knew something about air-engines and engineering?”

I didn’t say anything and after staring at me for a moment he said impatiently, “Well, do you know anything about air-engines or don’t you?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Practical — or just theory? Given specifications and tools can you build an engine?”

“What are you getting at?” I asked. “What do you—”

“Just answer my questions. Can you operate a lathe, do milling, grinding and boring, screw cutting and drilling?”

“Yes.” And then I added, “I don’t know very much about jets. But I’m pretty sound on all types of piston engines.”

“I see. And you’re a pilot?”

“Yes.”

“When did you become a pilot?”

“In 1945, after I escaped from Germany.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. I wanted a change. In 1944 I was posted to bombers as flight engineer. I started learning to fly. Then we were shot down. I escaped early in 1945 and remembered enough about flying to pinch a Jerry plane and crash-land at an airfield back home. Shortly after that I got my wings.”

He nodded vaguely as though he hadn’t been listening. He had turned slightly on his stool and was staring somberly at the gleaming fuselage of the Tudor. His eyes caught a shaft of sunlight from the high windows and seemed to gleam with some inner fire. Then he turned back to me. “You’re in a spot, aren’t you?” It wasn’t said unpleasantly — more a statement of fact. “But I’ll make you a proposition. See that engine over there?” I turned. It stood against the wall and was chocked up on wooden blocks. “That’s finished — complete. It’s hand-built, mostly right here in this hangar. Well, that’s one of them. But there’s got to be another before I can get this crate into the air.” He nodded towards the Tudor. “It’s due to fly on the Berlin Airlift on 25th January — fuel freighting. We’ve got the tanks installed. Everything’s ready. All we need is a second engine. We’ve started on it already. But I’m pressed for time. That first one took us six months. And now Carter, who’s been working on it with me, is getting impatient. I’m a pilot, not an engineer. If he walks out on me, which is what he threatens to do, I’ll have to pack up — unless I’ve got somebody else to carry on.” He looked at me, eyes narrowed slightly. “Well, what about it? Can you build another engine like that, if necessary on your own?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I haven’t examined it and I don’t know what equipment you’ve got.” My eyes roved quickly along the bench, noting the lathes, the racks of taps, boxes of dies, the turning tools, the jigs and the welding equipment. “I should think I could,” I added.

“Good.” He got up as though it were settled and went over to the completed engine. He stood there staring at it, and then he turned away from it with a quick, impatient movement of his shoulders as though throwing off something that was constantly at the back of his mind. “You won’t get any pay. Free board and lodging, beer, cigarettes, anything that is absolutely necessary. You’ll work up here until the thing’s complete. After that… well, we’ll see. If things work out the way they should, then you won’t lack a permanent job if you want it.”

“You seem to be taking my acceptance rather for granted,” I said.

“Of course I am,” he said, swinging round on me. “You’ve no alternative.”

“Look—just what’s your racket?” I demanded. Tm in enough trouble without getting deeper —”

“There’s no racket,” he cut in angrily. “I run a company called Saeton Aircraft Ltd., and I rent these premises from the Air Ministry. It’s all perfectly legal.”

“Then why pick on a lonely spot like this? And last night — you were scared of something. And you shouted at me in German. Why in German? And who was the girl?”

He came towards me then, his head thrust forward, his thick neck hard with the tautness of the muscles. “Take my advice, Fraser — accept my offer and don’t ask questions.” His jaw was so tight that the words came through his teeth.

I had got to my feet now. “Are you sure you haven’t pinched this plane?” I asked. Damn it! He wasn’t going to get me in a worse mess.

For a moment I thought he was going to strike me. But instead he turned away with a little laugh. “No. No, I didn’t pinch it.” He rounded on me and added violently, “Nor this engine, nor these tools, all this equipment. There’s three years of my life in this hangar — three years of sweating my guts out, improvising, struggling, trying to make fools see that if only…” He stopped suddenly. Then in a voice into which he had forced mildness he said, “You’ve nothing to worry about, Fraser. It’s all perfectly legal. And once this plane is in the air and —” He was interrupted by someone banging on the hangar door. He hesitated and then glanced at me. “That could be the police. Which is it to be — complete the second engine for me or do I hand you over? You’ll be quite safe up here in a day or so,” he added.

The banging on the door seemed to merge with the hammering of my heart. The possibility of arrest, which had gradually receded, now became real and instant. But I had already succumbed to a flicker of hope that had grown up inside me. “Ill stay,” I said.

He nodded as though there had never been any doubt of it. “Better nip into the fuselage. You can hide in the toilet at the rear. They won’t think of looking for you there.”

I did as he suggested and climbed into the fuselage. In the dark belly of the plane I could just make out the shape of three large elliptical tanks up for’ard. I heard the click of the door being opened and the sound of voices. The door slammed to and for a moment I thought they’d left the hangar. But then their footsteps were echoing on the concrete as they came down towards the bench. There was the drone of a man’s voice, low and urgent. Then Saeton cut him short: “All right. Throw in your hand if you want to. But we’ll talk about it back at the quarters, not here.” His voice was hard and angry.

“For God’s sake, Bill, be reasonable. I’m not throwing in my hand. But we can’t go on. You know that as well as I do.” They had stopped close beside the fuselage. The man was breathing heavily as though he were out of breath. He had a slight cockney accent and his voice was almost pleading. “Can’t you understand — I’m broke. I haven’t a bean.”

“Well, nor have I,” Saeton said harshly. “But I don’t whine about it. In three months from now…”

“It’s been two years already,” the other put in mildly.

“Do you think I don’t know how long it’s been?” Saeton’s voice softened. “Listen, Tubby, in three months we’ll be on top of the world. Think of it, man — only three months. Surely to God you can pull in your belt and stick it as long as that after all we’ve been through together?”

The other grunted. “But you’re not married, are you chum?”

“So your wife’s been getting at you. That’s it, is it? I ought to have known it. Well, if you think your wife’s going to stop me from getting that plane into the air…” Saeton had been lashing himself into a fury, but he stopped suddenly. “Let’s go back to the quarters. We can’t talk here.”

“No,” the other said obstinately. “I’ll say what I’ve got to say here.”

“We’re going back to quarters,” Saeton said gently. “Well talk about it over a cup of tea.”

“No,” the other repeated, still in the same obstinate tone. “We’ll talk it over here and now if you don’t mind. I’m not going to have you rowing Diana for something that isn’t her…”

“Diana!” Saeton’s voice was suddenly harsh. “You haven’t brought her back…”

“She’s down at the quarters now,” the other said stolidly.

“At the quarters! You bloody fool! This is no place for a woman. They can’t keep their mouths shut and —”

“Diana won’t talk. Besides, she’s nowhere else to go.”

“I thought she was sharing a flat with a friend in London.”

“Damn it, man,” the other shouted, “can’t you understand what I’m trying to tell you? We’re broke. I’m overdrawn by twenty quid and the bank has warned me I’ve got to settle my overdraft within three months.”

“What about your wife? Didn’t she have a job?”

“She got fed up and chucked it.”

“And you’re supposed to throw up all you’ve worked for just because she’s bored. That’s typical of a woman. If you can take it, why can’t she? Doesn’t she under stand…”

“It’s no good kicking at Diana,” the other cut in. “She’s not to blame. She’s stuck it pretty well if you ask me. Now it’s come to this — either I find a job that’ll bring us in some money so that we can live together like normal human beings, or else…”

“I see.”

“You don’t see at all,” the other snapped, his voice rising on a note of anger. “All you can think of is the engines. You’re so crazy about them you don’t behave like a human being at all. Well, I’m not made that way. I’m married and I want a home. I’m not busting up my marriage because of your engines.”

“I’m not asking you to go to bed with them, am I?” Saeton snarled. “Well, all right. If you’re so in love with your matrimonial pleasures that you can’t see the future that’s within your grasp…”

“I think you’d better withdraw that remark.” The man’s voice was low and obstinate.

“Oh God!” Saeton exploded “All right, I withdraw it. But for Christ’s sake, Tubby, stop to think what you’re doing.”

It seemed to me it was about time I showed myself. I slammed the toilet door and stumped across the steel-sheeted floor of the plane. From the open door of the fuselage I could see them standing, staring up at me. Saeton’s companion was dressed in an old pair of gray flannels and leather-patched sports jacket — a round, friendly little man with a shock of unruly hair. His fresh, ruddy complexion contrasted oddly with Saeton’s hard, leathery features. By comparison he looked quite boyish though he was about my age. Little creases of fat crinkled the corners of his eyes giving them a permanent twinkle as though he were perpetually on the verge of laughter. “Who’s this?” he asked Saeton.

“Neil Eraser. He’s an engineer, and he’s come up here to work with us on that last engine.”

“My successor, eh?” the other said quickly. “You knew I’d be leaving.”

“Don’t be a fool. Of course, I didn’t. But I knew time was getting short. With an extra hand…”

“How much are you paying him?”

“Oh, for God’s sake!” Saeton explained angrily. “His keep. That’s all.” He turned to me. “Fraser. This is Tubby Carter. He built the engine I’ve just shown you. Did you fix that toilet door?”

“Yes,” I said. “It’s all right now.” I got down and shook Carter’s hand.

“Fraser is an old friend of mine,” Saeton explained.

Carter’s small, button-brown eyes fixed themselves on my face in a puzzled frown. “You look as though you’ve been in a rough house.” His eyes stared at me, unwinking, as I searched desperately for some reasonable explanation.

It was Saeton who supplied the answer. “He got mixed up in some trouble at a night-club.”

But Carter’s eyes remained fixed on my face. “Neil Fraser.” He seemed to be turning the name over in his mind and my heart sank. Suppose the police had discovered who Callahan was. After all, I’d only seen one of the daily papers. “Are you a pilot by any chance?”

I nodded.

“Neil Fraser.” His face suddenly lit up and he snapped his fingers. “101 Bomber Squadron. You were the type who made a tunnel escape from prison camp and then pinched a Messerschmitt and flew it back to England. We met once — remember? At Mildenhall.” He turned to Saeton. “How’s that for a photographic memory, eh? I never forget a face.” He laughed happily.

Saeton glanced at me with sudden interest. Then he turned to Carter. “You stay here with Fraser and talk over your boyhood memories. I’m going to have a word with Diana.”

“No, you don’t, Bill.” Carter had caught his arm as he turned away. “This is between you and me. You leave Diana out of this.”

Saeton stopped. “It’s all right, Tubby,” he said and his voice was almost gentle. “I won’t upset your wife, I promise you. But before she forces you into some dead-end job she must be given the facts. The situation has altered since you left on Saturday. With Fraser here we can still get on to the airlift on schedule.”

“It took us six months to build that one.” Carter nodded to the completed engine.

“That included tests,” Saeton answered. “And we came up against snags. Those have been ironed out now. Damn it, surely she’ll have the sense to give you two months longer. As for money, leave that to me, I’ll wring some more out of Dick if I have to squeeze it out of him with my bare hands. It’s a pity he’s such a —” He stopped abruptly, his lips compressed as though biting on the words. “You stay here. I’ll talk to Diana. She’s no fool. No woman is when it comes to looking to the future. We’ve got all the metal and castings. All we’ve got to do is build the damned thing.” His eyes swung towards the plane. “Then well have ’em all licked.” He stood staring at it as though by mere effort of will he could get it into the air. Then almost reluctantly his gaze came back to Carter. “You can have that front room that used to be the office. It’ll work out. You’ll see. She can do the cooking for us. That’ll keep her busy, and it’ll give us more working time.”

“I tell you, her mind’s made up,” Carter said wearily. Saeton laughed. It was a slightly cynical laugh. “No woman’s mind is ever made up,” he said. “They’re constructed for the purpose of having their minds made up for them. How else do you imagine the human race survives?”

Carter stood quite still watching Saeton as he left the hangar. Then he turned and went straight over to the end of the workbench by the telephone and took down a pair of overalls. As he got into them he glanced at me curiously. “So you’re an engineer?” He zipped up the front of the overalls. Then he went over to a small petrol engine and started it up. “We’re working on the pistons at the moment.” He pulled a big folder towards me across the bench and opened it out. There were sheafs of fine pencil drawings. “Here we are. Those are the specifications. You can work a lathe?” I nodded. He took me down the bench. The lathe was an ex-R.A.F. type, the sort we’d had in the maintenance hangar at Kenly. The belt drive was running free. With a quick movement of his hand he engaged it and at the same time picked up a half-turned block of bright metal. “Okay, then. Go ahead. Piston specifications: five-inch diameter, seven-inch depth, three-ring channels, two to be drilled for oil disposal, and there’s a three-quarter inch hole for the gudgeon-pin sleeve. And for the love of Mike don’t waste metal. This outfit’s running on a shoe-string, as you’ve probably gathered.”

It was some time since I’d worked at a lathe. But it’s a thing that once you’ve learnt you never forget. He stood over me for a time and it made me nervous. But as the shavings of metal ran off the lathe my confidence returned. My mind ceased to worry about the events of the last twenty-four hours. It became concentrated entirely in the fascination of turning a piece of mechanism out of a lump of metal. I ceased to be conscious of his presence. Hands and brain combined to recapture my old skill, and pride of craftsmanship took hold of me as the shape of the piston slowly emerged from the metal.

When I looked up again Carter was leaning over the specifications, his eyes staring at a bolt he was screwing in and out of a nut. His mind was outside the shop, worrying about his own personal problems. He looked up and caught my eye. Then he threw the bolt down and came towards me.

I bent to my work again and for a time he stood watching me in silence. At length he said, “How long have you known Saeton?”

I didn’t know what to say so I didn’t answer him. “Saeton was a Coastal Command pilot.” The metal whirled under my hands, thin silver slivers streaming from it. “I don’t believe you’ve ever met him before in your life.”

I stopped the lathe. “Do you want me to balls this up?” I said.

He was fidgeting with the metal shavings. “I was just wondering—” He stopped then and changed his line of approach. “What do you think of him, eh?” He was looking directly at me now. “He’s mad, of course. But it’s the madness that builds empires.” I could see he worshipped the man. There was a boy’s admiration in his voice. “He thinks he’ll lick every charter company in the country once he gets into the air.”

“They’re most of them on the verge of bankruptcy anyway,” I said.

He nodded. “I’ve been with him for two years now. Working in partnership, you know. We had one plane flying — single-engined job. But that crashed.” His fingers strayed back to the metal shavings. “He’s a crazy devil. Incredible energy. The hell of it is his enthusiasm is infectious. When you’re with him you believe what he wants you to believe. Did you hear what we were talking about when you were fixing that door?”

“Part of it,” I said guardedly.

He nodded absently. “My wife’s got a will of her own. She’s American. Do you think he’ll persuade her to agree to give me three months more?” He picked up a block of metal destined to be the next piston. “He’s right, of course. With the three of us working at it we ought to be able to complete the second engine in two months.” He sighed. “Having come this far I’d like to see it through to the end. This place has become almost a part of me.” He turned slowly and stared at the tailplane of the aircraft. “I’d like to see her flying.”

I couldn’t help him so I started the lathe again and he moved off along the bench and began work on an induction coil.

Half an hour later Saeton returned. He came and stood over me as I measured the diameter of the piston-head with a screw micrometer. Carter moved along the bench. “Well?” he asked, his voice hesitant.

“Oh, she agrees,” Saeton said. His manner was offhand, but when I glanced at him I saw that he was pale as though he’d driven himself hard to get her agreement. “She’ll bring lunch up to us here.”

Carter stared at him almost unbelievingly. Then suddenly his eyes crinkled and his face fell into its natural mold of smiling good humor. “Well, I’m damned!” he said and went whistling down the bench back to his induction coil.

“I see you know how to handle a lathe,” Saeton said to me. And then with sudden violence, “By God! I believe we’ll do it in a couple of months.”

And then the phone rang.

He started and the light died out of his face as though he were expecting this call. He went slowly down the bench and lifted the receiver. His face gradually darkened as he bent over the instrument and then he shouted, “You’re selling out on me? Don’t be a fool, Dick… Of course, I understand… But wait a minute. Listen, damn you! I’ve got another man up here. Two months, that’s all I’m asking… Well, six weeks then… No, of course I can’t guarantee anything. But you’ve got to hang on a bit longer. In a couple of months we’ll have it in the air… Surely you can hang on a couple of months? … All right, if that’s the way you feel. But come down and see me first… Yes. A thing like this needs talking over… Tomorrow, then. All right.”

He replaced the receiver slowly. “Was that Dick?” Carter asked.

Saeton nodded. “Yes. He’s had an offer for the aircraft and all the equipment here. He’s threatening to sell us up.” He picked up a stool and sent it spinning across the hangar. “God damn him, why can’t he understand we’re on the verge of success at last?”

Carter said nothing. I returned to my lathe. Saeton hesitated and then seized hold of the folder of specifications. For a moment he held it in his hands as though about to tear it across. His face was dark with passion. Then he flung it down and went over to the engine standing on its blocks against the wall. He pressed a switch and the thing roared into life, a shattering, earsplitting din that drowned all sound of my lathe. And he stood watching it, caressing it with his eyes as though all his world was concentrated in the live, dinning roar of it.

* “Picture of you with Waaf girlfriend.” — The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was the female auxiliary of the Royal Air Force during World War II, established in 1939.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”