Air Bridge (10)

By:

May 2, 2015

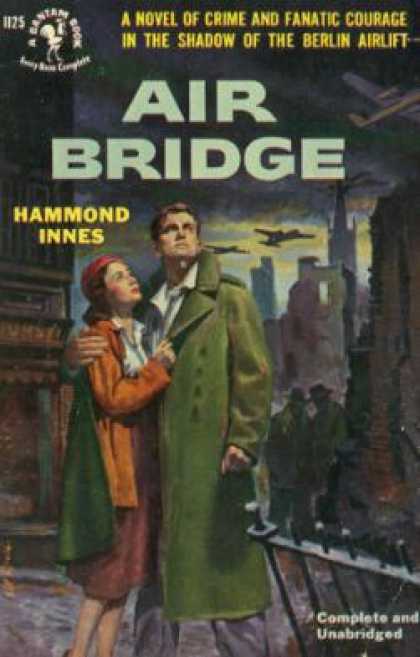

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Hammond Innes’s 1951 espionage thriller/Robinsonade Air Bridge. Set in England during the Berlin blockade and airlift of 1948–49 (during which time the British RAF and other aircrews frustrated the Soviet Union’s attempt to gain practical control of that city), the novel’s protagonist is a mercenary pilot… but is he a traitor? Hammond Innes wrote over 30 adventures, many of them set in hostile natural environments. Enjoy!

The coffee was thick and sweet. With it was a potted meat sandwich and a highly-colored cake full of synthetic cream. “Cigarettes?” I said, offering him a packet.

“Well, thanks. That’s one of the troubles here in Berlin. Cigarettes are damned hard to come by. And it’s worse for your boys. They’re down to about fifteen a day. Well, what do you think of Gatow?” He laughed when I told him I was disappointed. “You expected to find it littered with aircraft, eh? Well, that’s organization. Tempelhof is the same. They’ve got it so that these German labor teams turn the planes round in about fifteen minutes.”

“What brings you out to Gatow?” I asked him. “Just paying Diana a visit?”

“Sort of. But I got a good excuse,” he added with a grin. “I had to interview a German girl who has just got a job out here as a checker in your German Labor Organization. Some trouble about her papers and we urgently need her down at Frankfurt. That’s why I came up to Berlin.”

“You’re not stationed here then?” I asked.

“No. I’m normally in the Zone. It’s nice and quiet down there — by comparison. I just been talking to your SIB major over there. The stories that man can tell!”

“What’s he doing up at Gatow?” I asked.

“Oh, there’s been some trouble with the Russians. This is your first trip, isn’t it? Well, you see those trees on the other side of the airfield?” He nodded through the windows. “That’s the frontier over there.”

“The Russian Sector?”

“No. The Russian Zone. Last night Red Army guards opened up on a German car just after it had been allowed through the frontier barrier into the British Sector. Then their troops crossed the frontier and pushed the car back into their Zone under the nose of the R.A.F. Regiment. Your boys are pretty sore about it.”

“You mean the car was shot up in British territory?” I asked.

He laughed. “Seems that sort of thing is happening every day in this crazy town. If they want somebody, they just drive into the Western Sectors and kidnap them.” The corners of his eyes crinkled. “From what I hear our boys do the same in the Eastern Sector.”

An R.A.F. orderly called to me from the door. “Two-five-two ready, sir.”

“Well, I guess that’s your call. Glad to have met you, Fraser.”

“Neil!” Diana caught hold of my arm. “Tubby has just told me — about the crash.” She glanced quickly at Tubby who was saying good-bye to her brother. “What’s Bill doing now?” she asked in a quick whisper. I didn’t know what to say so I kept my mouth shut. “Oh, don’t be silly. I’ve got over that. But I know how it must have hit him. Where is he now?”

“He’s still at Membury,” I said. And then added, “He’s sticking the plane together with sealing wax.”

“You don’t mean to say he’s still going on with it?”

“Look — I’ve got to go now,” I said. “Good-bye, Diana.”

She was staring at me with a puzzled frown. “Goodbye,” she said automatically.

Outside it was still raining. We climbed into the plane and taxied out to the runway. “You’re clear to line up now, Two~five-two. Two-six-O a-concrete — angels three-five.” We flew out along the single exit corridor and were back in Wunstorf in good time for lunch. A letter was waiting for me at the mess. The address was typed and the envelope was postmarked “Baydon.” Dear Neil. Just to let you know I have almost completed the break-up. I have a flare path now. All you have to do is buzz once and I’ll light you in. Good luck. Bill Saeton. As I folded the letter Tubby came into the room. “Message from Harcourt. We’re not on the 1530 wave. He’s switched us to 2200. Says the other boys need a night’s sleep.”

So it had come. I had a sudden sick feeling.

He peered at me anxiously. “You feeling all right, Neil?”

“Yes. Why?”

“You look pretty pale. Not nervous, are you? Damn it, you’ve no reason to be. You had enough experience of night flying during the war.” His gaze fell to the letter in my hand but he didn’t say anything and I tore it into small pieces and stuffed them into my pocket.

“Better turn in then if we’re going to fly all night,” I said.

But I knew I shouldn’t sleep. Hell! Why did I have to agree to this damn-fool scheme? I was scared now. Not scared of the danger. I don’t think it was that. But what had seemed straightforward and simple over a drink in the pub at Ramsbury seemed much more difficult now that I was actually a part of the airlift. It seemed utterly crazy to try and fly a plane out of this organized bus service of supply delivery. And I had to convince a crew. that included Tubby Carter that they had got to bail out over the Russian Zone. The menace of the Zone had already gripped me. I lay and sweated on my bed, listening to the 1530 wave taking off, knowing that mine was the next wave, scared that I should bungle it.

At tea I could eat nothing, but drank several cups, smoking cigarette after cigarette, conscious all the time of Tubby watching me with a puzzled, worried expression. Afterwards I walked down to the field in the gathering dusk and watched the planes pile in, a constant stream of aircraft glimmering like giant moths along the line of the landing lights. I saw my own plane, Two-five-two, come in, watched it swing into position on the loading apron and the crew pile out, and I hung on, waiting for the maintenance crew to finish servicing it. At last it stood deserted, a black shape against the wet tarmac that glistened with the reflection of the lights. I climbed on board.

Saeton and I had discussed this problem of simulating engine failure at great length. The easiest method would have been simply to cut off the juice. But the fuel cocks were on the starboard side, controlled from the flight engineer’s seat. We had finally agreed that the only convincing method was to tamper with the ignition. I went forward to the cockpit and got to work on the wiring behind the instrument panel. I had tools with me and six lengths of insulated wire terminating in small metal clips. What I did was to fix two wires to the back of three of the ignition switches. These wires I led along the back of the instrument panel and brought out at the extreme left on my own side. All I had to do when I wished to simulate engine failure was to clip each pair of wires together and so short out the ignition switches. That would close the ignition circuit and stop the plugs sparking.

It took me the better part of an hour to fix the wires. I was just finishing when a lorry drove up. There was the clatter of metal and the drag of a pipe as they connected the fuel lorry to the tanks in the port hand wing. The lorry’s engine droned as it began refueling.

I waited, conscious already of a fugitive, guilty feeling. Footsteps moved round the plane. Rather than be caught crouched nervously in the cockpit of my own machine, I went aft down the fuselage, climbing round the three big elliptical tanks and dropping on to the asphalt. I started to walk away from the plane, but the beam of a torch picked me out and a voice said, “Who’s that?”

“Squadron-Leader Fraser,” I answered, reverting automatically to my service title. “I’ve just been checking over something.”

“Very good, sir. Good-night.”

“Good-night,” I answered and went hurriedly across to the terminal building and along the road to the mess. I went up to my room and lay on my bed, trying to read. But I couldn’t concentrate. My hands were trembling. Time dragged by as I lay there chain-smoking. Shortly after seven-thirty the door opened and Westrop poked his head into the room. “You coming down to dinner, sir?”

“May as well,” I said.

As we went down the echoing corridors and along the cinder paths to the mess, Westrop chattered away incessantly. I wasn’t listening until something he said caught my attention. “What’s that about a crash?” I asked.

“Remember when we arrived here yesterday — the station commander was talking about a Skymaster that was missing?” he said. “Well, they made a forced landing in Russian territory. I got it from a flight lieutenant who’s just come off duty at Ops. One of our crews sighted the wreck this afternoon. The Russians have apparently denied all knowledge of it. What do you think happens to crews who get landed in the Russian Zone?”

“I don’t know,” I said shortly.

“The flight lieutenant said they were probably being held for interrogation. He didn’t seem worried about them. But they might be injured. Do you think the Russians would give them medical treatment, sir? I mean” — he hesitated — “well, I wouldn’t like to have a Russian surgeon operate on me, would you?”

“No.”

“What do you think they hope to gain by this sort of thing? Everybody seems convinced they’re not prepared to go to war yet. They’ve stopped buzzing our planes. That seems to prove it. They got scared when they crashed that York. I was talking to an R.E. major this afternoon. He said the trouble was their lines of communication. Their roads are bad and their railways from Russia to Eastern Germany are only single track. But I think it’s more than that, don’t you, sir? I mean, they can’t possibly be as good as us technically. They could never have organized a thing as complicated as the airlift, for instance. And then their planes — they’re still operating machines based on the B 29’s they got hold of during the war.” He went on and on about the Russians until at length I couldn’t stand it. any more. “Oh, for God’s sake,” I said. “I’m sick and tired of the Russians.”

“Sorry, sir, but —” He paused uncertainly. “It’s just — well, this is my first operational night flight.”

It was only then that I realized he’d been talking because he was nervous. I thought: My God! The poor kid’s scared stiff of the Russians and in a few hours’ time Tm going to order him to jump. It made me feel sick inside. Why wasn’t my crew composed entirely of Field. I didn’t care about Field. I’d have ordered him to jump over wartime Berlin and not cared a damn. But Tubby and this child…

I forced myself to eat and listened to Westrop’s chatter all through the meal. He had a live, inquiring mind. He already knew that we had to cover seventy miles of the Russian Zone in flying down the Berlin approach corridor. He knew, too, all about Russian interrogation methods — the round-the-clock interrogation under lights, the solitary confinement, the building up of fear in the mind of the victim. “They’re no better than the Nazis, are they?” he said. “Only they don’t seem to go as far as physical torture — not against service personnel.” He paused and then said, “I wish we wore uniform. I’m certain, if anything like that happened, we’d be better off if we were in R.A.F. uniform.”

“You’ll be all right,” I answered without thinking.

“Oh, I know we shan’t have to make a forced landing,” he said quickly, mistaking what had been in my mind. “Our servicing is much better than the Yanks and —”

“I wouldn’t be too sure of that,” I cut in. “Have a cigarette and for God’s sake stop talking about forced landings.”

“I’m sorry, sir. It was —” He took the cigarette. “You must think me an awful funk. But it’s odd — I always like to know exactly what I’m facing. It makes it easier, somehow.”

Damn the kid! I’d always felt just like that myself. “I’ll see you at the plane at 21:46,” I said and got quickly to my feet. As I went out of the dining-hall I glanced at my watch. Still an hour to go! I left the mess and walked down to the airfield. The night was cold and frosty, the sky studded with stars. The apron was full of the huddled shapes of aircraft, looking clumsy and unbeautiful on the ground. Trucks were coming and going as the RASO teams worked to load them for the next wave. I leaned on the boundary fence and watched them. I could see my own plane. It was the left-hand one of a line of Tudors. Fuel loading and maintenance crews had completed their work. The planes stood deserted and silent. The minutes dragged slowly by as I stood, chilled to the marrow, trying to brace myself for what I had to do.

The odd thing is I never thought of refusing to carry out my part of the plan. I could have raised technical difficulties and put it off until gradually Saeton lost heart. Many times since I have asked myself why I didn’t do this, and I still don’t really know the answer. I like to think that Saeton’s threat of exposing my identity to the police had nothing to do with it. Certainly the audacity of the thing had appealed to me. Also I believed in Saeton and his engines and the airlift had only served to increase their importance in my eyes. Moreover, my own future was involved. I suppose the truth is that my attitude was a combination of aU these things. At any rate, as I stood there on the edge of Wunstorf airfield waiting for zero hour, it never occurred to me not to do it.

At last my watch told me it was nine-fifteen. I went slowly back to the mess. Tubby came in as I was getting into my flying kit. “Well, thank God the weather’s cleared,” he said cheerfully. “I wouldn’t want to be talked down by GCA the first time we went in by night.” GCA is Ground Control Approach, a means of blind landing where the plane lands on instructions from an officer operating radar gear at the edge of the runway.

By nine-fifty we were climbing into the plane. Our take-off time was 22:36 and as I lifted the heavy plane into the starlit night my hands and stomach felt as cold as ice. Tubby was checking the trim of the engines, his hand on the throttle levers. I groped down and found one of my three pairs of wires and touched the ends of them together. The inboard port motor checked. It worked all right. I glanced quickly at Tubby. He had taken his hand from the throttles and was listening, his head on one side. Then he turned to me. “Did you hear that engine falter?” he shouted.

I nodded. “Sounded like dirt in the fuel,” I called back.

He stayed in the same position for a moment, listening. Then his hand went back to the throttles. I glanced at the airspeed indicator and then at my watch. Three-quarters of an hour to Restorf beacon at the entrance of the air corridor.

The time dragged. The only sound was the steady drone of the engines. Twice I half-cut the same motor out. On the second occasion I did it when Tubby had gone aft to speak to Field. I held the wires together until the motor had cut out completely. Tubby suddenly appeared at my elbow as I allowed it to pick up again. “I don’t like the sound of that engine,” he shouted.

“Nor do I,” I said.

He stood quite still, listening. “Sounded like ignition. I’ll get it checked at Gatow.”

I glanced at my watch. It was eleven-sixteen. Any minute now. Then Field’s voice crackled in my ears. “We’re over the corridor beacon now. Right on to 100 degrees. We’re minus ten seconds.” I felt ice cold, but calm, as I banked. My stomach didn’t flutter any more. I leaned a little forward, feeling for the metal clips. One by one I fastened them together in their pairs. And one by one the engines died, all except the inboard starboard motor. The plane was suddenly very quiet. I heard Tub-by’s muttered curse quite distinctly. “Check ignition!” I shouted to him. “Check fuel!” I made my voice sound scared. The airspeed indicator was dropping, the luminous pointer swinging back through 150, falling back towards the 100 mark. The altimeter needle was dropping, too, as the nose tilted earthwards. “We’re going down at about 800 a minute,” I shouted.

“Ignition okay,” he reported, his hand on the switches. “Fuel okay.” His eyes were frantically scanning the instrument panel. “It’s an electrical fault — ignition, I think. The bastards must have, overlooked some loose wiring.”

“Anything we can do?” I asked. “We’re down to three thousand already.”

“Doubt it. Not much time.”

“If you think there’s anything we can do, say so. Otherwise I’m going to order the crew to bail out.” I had kept my inter-com mouthpiece close to my lips so that Field and Westrop could hear what we were saying.

Tubby straightened up. “Okay. We’d better bail out.” His face looked stiff and strained in the light of the instrument panel.

“Get your parachutes on,” I ordered over the intercom. “Field. You go aft and get the fuselage door open. We may have to ditch her.” Out of the tail of my eye I saw the two of them struggling with their parachutes. Field shouted something to Westrop and a moment later the bags containing the other two parachutes were slid on to the floor of the cockpit. “Get back to the fuselage door,” I told Westrop. “I’ll send Carter aft when I want you to jump.” I glanced at the altimeter dial. “Height two-six,” I called to Tubby.

He straightened up. “Nothing I can do,” he said. “It’s in the wiring somewhere.”

“Okay,” I said. “Get aft and tell the others to jump. Give me a shout when you’re jumping.”

He stood there, hesitating for a moment. “Okay.” His hand gripped my arm. “See you in the Russian Zone.” But he still didn’t move and his hand remained gripping my arm. “Would you like me to take her while you jump?” he asked.

I realized suddenly that he was remembering the last time I’d jumped, over Membury. He thought my nerve might have gone. I swallowed quickly. Why did he have to be so bloody decent about it? “Of course not,” I said sharply. “Get aft and look after yourself and the others.”

His eyes remained fixed on mine — brown, intelligent eyes that seemed to read my mind. “Good luck!” He turned and dived quickly through towards the fuselage. Leaning out of my seat, I looked back and watched him climbing round the fuel tanks. I could just see the others at the open door of the fuselage. Tubby joined them. Westrop went first, then Field. Tubby shouted to me. “Jump!” I called to him. The plane skidded slightly and I turned back to the controls, steadying her.

When I looked back down the length of the fuselage there was no one there. I was alone in the plane; I settled myself in my seat. Height one thousand six hundred. Airspeed ninety-five. I’d take her down to a thousand feet. That should put her below the horizon of the three who had jumped. Through the windshield I saw a small point of light moving across the sky — the tail-light of one of the airlift planes holding steadily to its course. I wondered if those behind could see me. In case, I banked away and at the same time broke one of the wire contacts. The outboard port engine started immediately as I unfeathered the prop.

As I banked out of the traffic stream a voice called to me — “You bloody fool, Neil. You haven’t even got your parachute on.” I felt sudden panic grip me as I turned to find Tubby coming back into the cockpit.

‘Why the hell haven’t you jumped?”

“Plenty of time now,” he said calmly. “Perhaps the other engines will pick up. I was worried about you, that’s why I came back.”

“I can look after myself,” I snapped. “Get back to that door and jump.”

I think he saw the panic in my eyes and misunderstood it. His gaze dropped to my parachute still in its canvas bag. “I’ll take over while you get into your parachute. With two engines we might still make Gatow.”

He was already sliding into the second pilot’s seat now and I felt his hands take over on the controls. “Now get your ’chute on, Neil,” he said quietly.

We sat there, staring at each other. I didn’t know what the hell to do. I glanced at the altimeter. The needle was steady at the thousand mark. His eyes followed the direction of my gaze and then he looked at me again and his forehead was wrinkled in a puzzled frown. “You weren’t going to jump, were you?” he said slowly.

I sat there, staring at him. And then I knew he’d got to come back to Membury with me. “No,” I said. And with sudden violence, “Why the hell couldn’t you have jumped when I told you?”

“I knew you didn’t like jumping,” he said. “What were you going to do — try and crash land?”

I hesitated. I’d have one more shot at getting him to jump. I edged my left hand down the side of my seat until I found the wires that connected to the ignition switch of that outboard port motor. I clipped them together and the motor died. “It’s gone again,” I shouted to him. I switched over to the automatic pilot. “Come on,” I said. “We’re getting out.” I slid out of my seat and gripped him by the arm. “Quick!” I said, half-pulling him towards the exit door.

I think I’d have done it that time, but he glanced back, and then suddenly he wrenched himself free of my grip. I saw him reach over the pilot’s seat, saw him tearing at the wires, and as he unfeathered the props the motors picked up in a thrumming roar. He slid into his own seat, took over from the automatic pilot and as I stood there, dazed with the shock of discovery, I saw the altimeter needle begin to climb through the luminous figures of its dial.

Then I was clambering into my seat, struggling to get control of the plane from him. He shouted something to me. I don’t remember what it was. I kicked at the rudder bar and swung the heavy plane into a wide banking turn. “We’re going back to Membury,” I yelled at him.

“Membury!” He stared at me. “So that’s it! It was you who fixed those wires. You made those boys jump ” The words seemed to choke him. “You must be crazy. What’s the idea?”

I heard myself laughing wildly. I was excited and my nerves were tense. “Better ask Saeton,” I said, still laughing.

“Saeton!” He caught hold of my arm. “You crazy fools! You can’t get away with this.”

“Of course we can,” I cried. “We have. Nobody will ever know.” I was so elated I didn’t notice him settling more firmly into his seat. I was thinking I’d succeeded. Td done the impossible — I’d taken an aircraft off the Berlin airlift. I wanted to sing, shout, do something to express the thrill it gave me.

Then the controls moved under my hands. He was dragging the plane round, heading it for Berlin. For a moment I fought the controls, struggling to get the ship round. The compass wavered uncertainly. But he held on grimly. He had great strength. At length I let go and watched the compass swing back on to the lubber lines of our original course.

All the elation I had felt died out of me. “For God’s sake, Tubby,” I said. “Try to understand what this means. Nobody’s going to lose over this. Harcourt will get the insurance. As for the airlift, in a few weeks the plane will be back on the job. Only then it will have our engines in it. We’ll have succeeded. Doesn’t success mean anything to you?” Automatically I was using Saeton’s arguments over again.

But all he said was, “You’ve dropped those boys into Russian territory.”

“Well, what of it?” I demanded hotly. “They’ll be all right. So will Harcourt. And so will we.”

He looked at me then, his face a white mask, the little lines at the corners of his eyes no longer crinkled by laughter. He looked solid, unemotional — like a block of granite. “I should have known the sort of person you were when you turned up at Membury like that. Saeton’s a fanatic. I can forgive him. But you’re just a dirty little crook who has —”

He shouldn’t have said that. It made me mad — part fear, part anger. Damn his bloody high and mighty principles! Was he prepared to die for them? I reached down for the wires. My fingers were trembling and numb with the cold blast of air that came in through the open doorway aft, but I managed to fasten the clips. The engines died away. The cabin was suddenly silent, a ghostly place of soft-lit dials and our reflections in the windshield. We seemed suddenly cut off from the rest of the world. A white pin-point of light slid over us like a star — our one contact with reality, a plane bound for Berlin.

“Don’t be a fool, Fraser!” Tubby’s voice was unnaturally loud in the stillness.

I laughed. It wasn’t a pleasant sound. My nerves were keyed to the pitch of desperation. “Either we fly to Membury,” I said, “or we crash.” My teeth were clenched. It might have been a stranger’s voice. “You can jump if you want to,” I added, nodding towards the rear of the cockpit where the wind whistled.

“Unfasten those wires!” he shouted. And when I made no move he said, “Get them unfastened and start the motors or I’ll hurt you.”

He was fumbling in the pocket beside his seat and his hand came out holding a heavy spanner. He let go the controls then. The plane dipped and slid away to port. Automatically I grasped the control column and righted her. At the same time he rose in his seat, the spanner lifted in his hand.

I flung myself sideways, lunging out at him. The spanner caught me across the shoulder and my left arm went numb. But I had hold of his flying suit now and was pulling him towards me. He had no room to use the spanner again. And at the same moment the plane dropped sickeningly. We were flung into the aisle and fetched up against the fuel tanks in the fuselage.

For a moment we stood there, locked together, and then he fought to get clear of me, to get back to start the motors again. I was determined he shouldn’t. I’d take him down into the ground rather than fly on to Gatow to be accused of having attempted to take a plane off the airlift. I clutched hold of him, pinning his arms, bracing myself against the tanks. The plane lurched and we were flung between the tanks into the main body of the fuselage where the wind roared in through the open doorway. That lurch flung us against the door to the toilet, breaking us clear of each other. He raised the spanner to strike at me again and I hit him with my fist. The spanner descended, striking my shoulder again. I lashed out again. My fist caught his jaw and his head jerked back against the metal v of the fuselage. At the same moment the plane seemed to fall away. We were both flung sideways. Tubby hit the side of the open doorway. I saw his head jerk back as his forehead caught a protruding section of the metal frame. Blood gleamed red in a long gash and his jaw fell slack. Slowly his legs gave under him.

As he fell I started forward. He was falling into the black rectangle of the doorway. I clutched at him, but the plane swung, jerking me back against the toilet door. And in that instant Tubby slid to the floor, his legs slowly disappearing into the black void of the slip-stream. For an instant his thick torso lay along the floor, held there by the wind and the tilt of the plane. I could do nothing. I was pinned by the tilt of the plane, forced to stand there and watch as his body began to slide outwards, slowly, like a sack, the outstretched hands making no attempt to hold him. For a second he was there, sliding slowly out across the floor, and then the slip-stream whisked him away and I was alone in the body of the plane with only the gaping doorway and a thin trickle of blood on the steel flooring to show what had happened.

I shook myself, dazed with the horror of it. Then I closed the door and went for’ard. Almost automatically my brain registered the altimeter dial: Height 700. I slipped into the pilot’s seat and with trembling fingers forced the wires apart. The engines roared. I gripped the control column and my feet found the rudder bar. I banked and climbed steeply. The lights of a town showed below me and the snaking course of a river. I felt sick at the thought of what had happened to Tubby. Height two-four. Course eight-five degrees. I must find out what had happened to Tubby.

I made a tight, diving turn and leveled out at five hundred feet. I had to find out what had happened to him. If he’d regained consciousness and had been able to pull his parachute release… Surely the cold air would have revived him. God! Don’t let him die. I was sobbing my prayer aloud. I went back along the course of the river, over the lights of the town. A road ran out of it, straight like a piece of tape and white in the moonlight. Then I shut down the engines and put down the flaps. This was the spot where Tubby had fallen. I searched desperately through the windshield. But all I saw was a deserted airfield bordered by pine woods and a huddle of buildings that were no more than empty shells. No sign of a parachute, no comforting mushroom patch of white.

I went back and forth over the area a dozen times. The airdrome and the woods and the bomb-shattered buildings stood out clear in the moonlight, but never a sign of the white silk of a parachute.

Tubby was dead and I had killed him.

Dazed and frightened I banked away from the white graveyard scene of the shattered buildings. I took the plane up to 10,000 feet and fled westward across the moon-filled night. Away to the right I could see the lines of planes coming in along the corridor, red and green navigation lights stretching back towards Lubeck. But in a moment they were gone and I was alone, riding the sky, with only the reflection of my face in the windshield for company — nothing of earth but the flat expanse of the Westphalian plain, white like a salt-pan below me.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”