Air Bridge (13)

By:

May 23, 2015

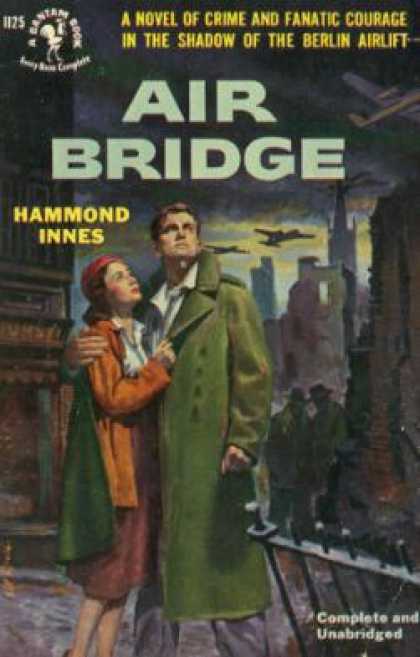

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Hammond Innes’s 1951 espionage thriller/Robinsonade Air Bridge. Set in England during the Berlin blockade and airlift of 1948–49 (during which time the British RAF and other aircrews frustrated the Soviet Union’s attempt to gain practical control of that city), the novel’s protagonist is a mercenary pilot… but is he a traitor? Hammond Innes wrote over 30 adventures, many of them set in hostile natural environments. Enjoy!

For a long time after the plane had disappeared I stood there on the fringe of the woods gazing at the empty expanse of the airfield. A small wind whispered in the upper branches of the fir trees and every few minutes there was the distant drone of a plane — airlift, pilots flying down the corridor to Berlin. Those were the only sounds. The cold seeped through my flying suit, stiffening my limbs, and at length I turned and walked into the woods. A few steps and I had lost the airfield. The trees closed round me and I was in a world apart. It was very still there in the woods, even the sound of my footsteps was muffled by the carpet of pine needles. I could still hear the planes, but I couldn’t see them. The branches of the trees cut me off from the sky and only a ghostly radiance told me that the moon still filled the world with its white light.

I found a path and followed it to the earth mound of an old dispersal point. The frost-cracked concrete was a white blaze in the moonlight, cutting through the dark ranks of the trees to the open plain of the airfield. I stopped there to consider what I should do. My mind went back to the scene in the plane. We had been flying almost due south when Tubby’s body slid through the open doorway. I had gone straight back to the cockpit and then I had looked through my side window and seen Hollmind airfield below me. That meant that Tubby had gone out north and slightly west of the field.

I followed the line of the concrete till I came out on to the edge of the airfield and turned left, walking in the shadow of the woods till I reached the north-west extremity of the field. Buildings began there, shapeless heaps of broken rubble. I skirted these and entered the woods again, following a path that ran in the direction I wanted to go.

It was four o’clock when I began my search. I remember thinking that Saeton would be at Wunstorf. The plane would be parked on the loading apron in the row of Tudors where it had stood before. Only the crew would be different — and the numbers and the engines. He’d be reporting to Ops and checking in at the mess, finding a bed in the echoing concrete corridors of that labyrinth that housed the human force of the airlift. He’d be one of them now, getting up when the world was asleep, going to bed when others were shaving. In a few hours perhaps it would be his plane I’d hear droning over on its way to Berlin. He’d be up there, with success ahead of him, while I was down in these grim, dark woods, searching for the body of the man who’d given two years to help him build those engines. Damn it, it wasn’t even his plane. It was my plane. Nothing was really his. Even the design of the engines he’d pinched from Else’s father.

Blind anger drove everything else out of my head for a moment. Then I steadied myself, forcing my mind to concentrate on the thing I’d set myself to do. I decided to walk east and west, backwards and forwards on a two mile front working gradually northwards. The impossibility of complete coverage was apparent from the start. I had a small pocket compass, that was all. The trees, fortunately, were well spaced out, but they were all alike. There was nothing to guide me. It was obvious that at some points I should be covering the same ground twice, maybe three times, while at other times I should be leaving large gaps uncovered. But it was the only course open to me and with a feeling of hopelessness I turned west on my first beat. It was past five when I came to the western fringe of the woods and looked across the dreary flatness of the Mecklenberg plain with the moon dipping over it towards the horizon. And in that time I had stopped a hundred times to investigate a deeper shadow, a dead branch that looked like an arm or a patch of white where a beam of direct moonlight shone on the bark of a pine trunk.

Dawn found me at the end of the eastward beat. The daylight penetrated slowly into the woods, a slight lightening of the deeper shadows, a paling of the moon’s whiteness. I didn’t really see it until I was in a clearing that showed me the bomb-battered ruins of the hangars that lay along the north fringe of Hollmind airfield. It was a gray dawn, still, but pitilessly cold, with great cloud banks rolling in from the north and the feel of snow in the air.

I ate two sandwiches and took a nip from the flask Saeton had given me. There was rum in that flask and I could feel the warmth of it trickling into my stomach. But as I turned again on my third beat I was already tired. There was no breath of wind. The woods seemed frozen into silence. The only sound was the drone of aircraft. That sound had been with me all the time. It was monotonous, unending. But God, how glad I was of it! That sound was my one link with the world, with reality. And as the daylight increased, I began to look for the planes in the gaps in the trees. At last I saw one. It was flying across my line of march at about three thousand feet, the thick belly unmistakable — a York. That meant that it had come from Wunstorf. The men in that plane would have breakfasted before dawn with the electric lights on and the mess warm with the smell of hot radiators and food. They had hot food in their bellies and hot coffee.

I stood there in the clearing, watching the plane till it was out of sight, the smell of coffee stronger than the smell of the pines, remembering a shop I’d known as a kid that had a big grinder always working in the window, spilling its fragrance into the street. As the plant disappeared over the tops of the trees another came into sight, exactly the same, flying the same route, flying the same height. I watched another and another. All Yorks. All exactly the same. It was as though they were on an endless belt going behind the trees, like those little white clay airgun targets you find at fairs.

The smell of coffee lingered with me as I went on into the somber gloom of the woods.

Shortly after midday it began to snow, the flakes drifting gently down out of the leaden sky, dark, widely-spaced specks until they landed and were transformed to little splashes of virgin white. It was less cold after the snow began to fall. But by then I was feeling sleepy, exhausted and hungry. There were two sandwiches left and half a flask of rum. I saved them for the night and stumbled on.

On my eighth beat I found a crumpled piece of metal. It was lodged in the branches of a tree — a piece of the tailplane of the Tudor Saeton had pranged at Membury. It didn’t seem possible that it was less than twelve hours since I’d slung that fragment out of the open door of the fuselage with these woods flashing by below me.

An hour later I nearly walked into a Russian patrol. I was almost on top of them before I heard the low murmur of their voices. They were in a group, short men with round, sallow faces, black boots and brown tunics buttoned to the neck. The soldiers leaned on their rifles while two officers bent over a piece of metal that gleamed dully.

I wondered what they’d make of these scraps of metal scattered through the woods as I slipped past them and continued eastward. The snow thickened and the sky darkened. Patches of white showed in the gaps between the trees and these I had to avoid for fear of leaving footprints. In the gathering darkness and my growing weakness every shadow became a Russian soldier. My progress became wretchedly slow. Finally it was too dark to go on and I dug a hole for myself close under the low-sweeping branches of a large fir and lay down in it, covering myself with pine needles.

I finished the two sandwiches and drank the rest of the rum. But within an hour the warmth of the rum had completely evaporated; the cold of the night moved in on me, gripping my limbs like a steel sheet. Sleep was impossible. I lay and shivered, my mind a blank, my body in a coma of misery. The cold covered everything. The snow became hard and powdery, the trees cracked.

By midnight I was so frozen that I got to my feet and stamped and swung my arms. My breath hung like smoke in front of my face. The snow clouds had passed. Stars shone frosty-clear above my head and the moon had risen showing me a beautiful, fairy-white world of Christmas trees.

I started moving westward, walking blindly, not really caring where I went so long as I got some warmth into my limbs. And that was how I found Tubby’s flying helmet. I just stumbled on it lying on a patch of snow. I suppose what had happened was that it had been caught on one of the branches of a tree and when the snow weighed the branch down it had slipped to the ground.

I don’t remember feeling any excitement. I think I was too numbed with cold to have any feelings at all. And I had no sense of surprise either. I had been so determined to find him that it hadn’t occurred to me that I should fail. I have always believed that if you go out for a thing hard enough, you get it in the end, and I didn’t bother to consider the virtual impossibility of the task I had set myself. But though I had found his helmet I could find no trace of Tubby himself. There was just the helmet. Nothing else.

After a thorough search of the area I returned to the spot where the helmet had lain. The trees were very thick and in the darkness of the shadows it was impossible to see whether there was anything lodged in the branches. In the end I climbed to the top of the tree that overhung the spot. With my head thrust above the snow-laden branches I looked over a plain of white spikes that glistened in the moonlight. By shaking the tree I got rid of most of the snow. The needle foliage looked very green, but there was no sign of anything that would prove that this was the spot where Tubby had fallen.

I was half-way down the tree, back in the world of half-light and shadows, when my hand slid from the gritty surface of the bark to something softer. My fingers closed on it, feeling the smoothness of light material. I didn’t need to look at it to know that this was nylon. I pulled at it and my hand came away with a torn strip of parachute silk about the length of a scarf.

I was excited then. That strip of nylon silk showed that Tubby had pulled his parachute release before he hit the ground and I went tumbling down the tree, oblivious of the snow that fell on my neck and trickled in icy streams down my back, oblivious of everything but that single fact—Tubby wasn’t dead. He might have hurt himself, but he’d regained consciousness, he’d pulled the release and his parachute had opened. And I realized then how the fear of finding him, a mangled, blood-stained heap of broken bones and torn flesh, had haunted me. In a frenzy I searched the area again, trampling the snow in my haste to find out what had happened to him after he’d crashed through the trees.

But the snow hid all trace.

At length, utterly exhausted, I sat down on a dry patch of ground with my back against the bole of a tree and lit one of my last cigarettes. I had searched the area in a circle extending about fifty yards from the spot where I had come upon the helmet. I had found no trace of him. Clearly one of two things had happened — either he had been all right and had left the area on foot or else he had been injured and some woodsman had found him and got him away. Or perhaps it had been the Russians who’d found him. Maybe the patrol I’d seen in the afternoon had come upon him and carted him off to Hollmind. The possibility that he might be dead was nagging at me again. I had to be sure that he was alive.

I got to my feet again. I would have to widen my search, radiate out until I found some trace. I began walking again, circling out from the spot where the helmet had lain. The snow helped me here, for all I had to do was walk outside the footprints I’d made on my previous circuit. The moon was high overhead now and it was much lighter under the trees. At four o’clock in the morning, after walking for over two hours in a widening circle, I stumbled upon a broad track running through the woods. One side of the track was sheltered by the trees arid was clear of snow and there I found the marks of a farm cart. I traced it back to a spot where it had stood for some time. The tracks did not continue. They finished there and I knew then that Tubby was either dead or injured. Cold and wretched, I turned westward and followed the track till it left the shelter of the woods and ran out into the bitter flatness of plowed land that was all white under the moon.

The wheel tracks were lost under the snow now, but the track was still visible — two deep ruts swinging south-west towards a Christmas card huddle of steep-roofed farm buildings. As I approached I saw the yellow glow of a light. It came from the half-open door of a barn. Inside the barn a man was filling sacks with potatoes from a deep, square hole in the floor. Wooden boards heavy with earth were stacked against the heaped-up straw and earth had been piled near the door.

The man must have sensed my presence, for he suddenly paused in his work and looked straight at me where I stood in the gaping doorway. He was short and wiry with a broad forehead and his eyes looked startled and afraid. “Wer sind Sie? Was wollen Sie?”

“I am an English flier,” I replied in German. “I am looking for a friend of mine who may be injured.”

He put down his fork and came towards me, his dark, frightened eyes peering first at my face, then at my clothes. “Come in then and close the door please. The wind blow it open I think.” He fixed the latch with trembling fingers. “I was afraid it was the Russians.” He laughed nervously. “They want everything — all my crops. For the East, you know.” His speech was jerky. “To feed our pigs we must keep something.” He held the lantern close to me, still examining me uncertainly. Apparently he was finally satisfied, for he lowered the lantern and said, “You look tired. You walk far, yes.”

“What has happened to my friend?” I asked. “He was brought here, wasn’t he? Is he — is he dead?” I waited, dreading his answer.

He shook his head slowly. “Nein. He is not dead. But he injure himself very much when he land in the trees. Now you lie down in the straw there. I must finish my work before it is light. Then I get you something to eat, eh?”

But I wasn’t listening. “Thank God!” I breathed it aloud. Tubby was alive. He was alive and Fd found him. I hadn’t killed him after all. I felt suddenly light-headed. I wanted to laugh. But once I started to laugh I felt I should never stop. I held my breath, fighting to control myself. Then I stumbled into the straw, sinking into it, relaxing, knowing I had done everything I could and that God had been with me. I had found Tubby and he wasn’t dead. “When did you find him?” I asked.

“Four days ago,” the man answered. He had returned to his work.

“And you have not handed him over to the Russians?”

He paused with a forkful of potatoes. “No, we do not hand him to the Russians. You have to thank my wife for that. Our daughter is in Berlin. She live in the French Sector with her husband who work on the railways there. But for the air bridge, she would be like us — she would be under the Russians.”

I mumbled my thanks. My head kept nodding. It was very warm and comfortable there in the straw. “Is he badly hurt?”

“Ja. He is not so good. Several ribs are broken and his arm and he has concussion. But he is conscious. You can speak with him.”

“He should have a doctor.” My voice sounded very far away. I couldn’t keep my eyes open.

“You do not have to worry. Our doctor is coming here to see him every day. He is a good doctor and he do not love the Russians because they take him to the East for a year to work with our prisoners. Once he meet my son. My son, Hans, is a prisoner of the Russians since 1945. Before that he is in North Africa and Italy and then on the Eastern front. I do not see him now for almost six years. But soon I hope he will come home. We have had two letters…”

His voice droned pleasantly and my eyelids closed. I dreamed I was back in Stalag Luft I, but the guards all wore tight-necked brown tunics and black knee-length boots, and there was always snow and no hope of release or escape — only the hope of death. They kept on interrogating me, trying to get me to admit that I’d killed Tubby — there were intensely bright lights and they kept on shaking me… I woke to find the farmer bending over me, shaking my shoulder. “Wake up, Herr Fraser.” He pronounced the “s” sharply and not as a “z.” “It is seven o’clock. We will have some food now and then you can talk with your friend.”

“You know my name?” I murmured sleepily. And then I felt in my breast pocket. My papers were still there. He must have put them back after examining them. I clambered stiffly to my feet. I was cold and very tired.

“I think perhaps we put your flying clothes under the straw, eh? I do not wish my men to know I have a British flier here. By talking, one of them might be given my farm. That is something they learn from the Nazis.” He said the “Nazis” unemotionally as one might talk of an avalanche or some other act of God.

When I had hidden my flying suit he took me across the farmyard to the house. It was a cold, bleak dawn, heavy with leaden cloud that promised more snow. Overhead I heard the drone of the planes flying in to Berlin, but I couldn’t see them, for the ceiling was not much more than a thousand.

My memory of the Kleffmann’s house is vague; a memory of warmth and the smell of bacon, of a big kitchen with a great, clumsy, glowing stove and a bright-eyed, friendly little woman with wisps of graying hair and the slow, sure movements of one who lives close to the earth and whose routine never changes. I also remember the little bedroom high up under the roof where Tubby lay, his fat cheeks strangely hollow, his face flushed with fever and his eyes unnaturally bright. The ugly, patterned wallpaper with butterflies flying up vertical strips was littered with photographs of Hans Kleffmann who would some day come back from Russia and meet his mother and father again for the first time in six years. There were photographs of him as a baby, as a boy at the school in Hollmind, in the uniform of the Nazi Youth Organization and finally in the uniform of the Wehrmacht — against the background of the Hradcany Palace in Prague, in a Polish village, with the Eiffel Tower behind him, in the Desert leaning on a tank, in Rome with St. Peter’s Dome over his left shoulder. And there were a few less formal snaps — Hans in bathing shorts on the Italian Riviera, Hans with a dark-haired girl in Naples, Hans ski-ing in the Dolomites. Hans filled that room with the nostalgia of a boy’s life leading inevitably, irrevocably to the Russian prison camp. They showed me a letter. It was four lines long — I am well and the Russians treat me very kindly. The food is good and I am happy. Love, Hans.

Tubby, lying in that small, neatly austere bed, was an intruder.

He was asleep when I went in. The Kleffmanns left me sitting by his bed while they got on with the business of the farm. Tubby’s breath came jerkily and painfully, but he slept on and I had a long time in which to become familiar with Hans. It’s almost as though I had met him, I got to know him so well from those faded photographs — arrogant and fanatical in victory, hard-faced and bitter in defeat. There in that room I was face to face with the Germany of the future, the Germany that was being hammered out on the vulcan forge of British, American and Soviet policy. I found my eyes turning back repeatedly to the grim, relentless face in the photograph taken at Lwow in the autumn of 1944 and comparing it with the smiling carefree kid in knickerbockers taken outside the Hollmind school.

Then Tubby opened his eyes and stared at me. At first I thought he wasn’t going to recognize me. We stared at each other for a moment and then he smiled. He smiled at me with his eyes, his lips, a tight line constricted by pain. “Neil! How did you get here?”

I told him, and when I’d finished he said, “You came back. That was kind of you.” He had difficulty in speaking and his voice was very weak.

“Are they looking after you all right?” I asked awkwardly.

He nodded slowly. “The old woman is very kind. She treats me as though I were her son. And the doctor does his best.”

“You ought to be in hospital,” I said.

He nodded again. “But it’s better than being in the hands of the Russians.”

“Thank God you’re alive anyway,” I said. “I thought —” I hesitated and then said, “I was afraid I’d killed you. You were unconscious when you went out through the door. I didn’t mean it, Tubby. Please believe that.”

“Forget it,” he said. “I understand. It was good of you to come back.” He winced as he took a breath. “Did you take the plane back to Saeton?”

“Yes,” I said. “It’s got our engines in now and Saeton’s at Wunstorf. They ordered him over immediately to replace Harcourt’s Tudor.”

His mouth opened to the beginning of a laugh and then he jerked rigid at the pain it caused him.

“You ought to be in hospital,” I said again. “Listen,” I added. “Do you think you could stand another journey in that cart, up to Hollmind airfield?”

I saw him clench his teeth at the memory.

“Could you stand it if you knew at the end there would be a hospital and everything in the way of treatment you need?”

The sweat shone on his forehead. “Yes,” he breathed, so quietly that I could hardly hear him. “Yes, I’d face it again if I knew that. Maybe the doc here would fix me up with a shot of morphia. But they have so little in the way of drugs. They’ve been very kind, but they’re Germans, and they haven’t the facilities for…” His voice trailed away.

I was afraid he was going to fade into unconsciousness and I said quickly, “I’m going now, Tubby. Tonight I’ll start out for Berlin. I’ll make it just as quickly as I can. Then, within a few hours, I’ll be back with a plane and we’ll evacuate you from Hollmind. Okay?”

He nodded.

“Good-bye then for a moment. I’ll get through somehow and then we’ll get you to a hospital. Hold on to that. You’ll be all right.”

The corners of his lips twitched in a tight smile. “Good luck!” he whispered. And then as I rose from the bed, his hand came out from beneath the sheets and closed on mine. “Neil!” I had to bend down to hear him. “I want you to know — I won’t say anything. I’ll leave things as I find them. The plane crashed. Engine failure — ignition.” His voice died away and his eyes closed.

Bending close to him I could hear the sob of his breathing. I reached under his pillow for his handkerchief to wipe the sweat from his forehead. The handkerchief was dark with blood. I knew then that his lung was punctured. I wiped his forehead with my own handkerchief and then went quietly out of Hans’s little bedroom and down the dark stairs to the kitchen.

They gave me a bed and I slept until it was dark. Then, after a huge meal by the warmth of the kitchen stove, I said good-bye to the Kleffmanns. “In a night or two,” I told them, “I will be back with a plane and we’ll get him away.”

“Gut! Gut!” The farmer nodded. “It is better so. He is very bad, I think. Also it is dangerous for us having him here in the farm.”

Frau Kleffmann came towards me. She had a bulky package in her hand. “Here is food for your journey, Herr Fraser — some chicken and some bread and butter and apples.” She hesitated. “If anything happens, do not worry about your friend. He is safe here. We will look after him. There has been war between us, but my Hans is in Russia. I will care for your friend as I would have others care for Hans if he is sick. Auf wiedersehen!” Her gnarled hand touched my arm and her eyes filled with tears. She turned quickly to the stove.

The farmer accompanied me to the door. “I try to arrange for you to ride in a lorry who go once a week to Berlin with potatoes. But” — he spread his hands hopelessly — “the driver is sick. He do not go tonight. If you go three miles beyond HoUmind there is a cafe there for motor drivers. I think you will perhaps get a ride there.” He gave me instructions how to by-pass Hollmind and then shook my hands. “Viel Glück, Herr Fraser. Come soon, please, for your friend. I fear he is very sick.”

More snow had fallen during the day, but now the clouds had been swept away by a bitter east wind and the night was cold and clear. The moon had not yet risen, but the stars were so brilliant that I had no difficulty in seeing my way as soon as my eyes became accustomed to the darkness. High above me the airlift planes droned at regular three-minute intervals — I could see their navigation lights every now and then, green and red dots moving steadily through the litter of stars and the drift of the Milky Way. The white pin-point of their tail-lights pointed the way to Berlin for me. I had only to follow them through the night sky and I should arrive at Gatow. For them Gatow was twenty minutes flying time. But for me….

I turned south on the hard straight road that led to the town of Hollmind, wondering how long the journey would take me. The snow was deep and crisp under my feet Kleffmann had given me an old field-gray Wehrmacht greatcoat and a Wehrmacht forage cap; Hans’s cast-off clothing. For the first time since I’d landed in Germany I felt warm and well-fed.

Nothing stirred on the road. The snow seemed to have driven all transport off it. My footsteps were muffled and I walked in a deep silence. The only sound was the drone of the planes overhead and the hum of the wind in the telegraph wires. I reached the fork where the road branched off that I was to take in order to by-pass Hollmind. There was a signboard there — Berlin 54 km.

Fifty-four kilometers isn’t far; not much more than thirty miles. A day’s march. But though I had had a good rest, I was still tired and very stiff. I was wearing shoes and my feet were blister-sore. And there was the cold. For a time the warmth of exercise kept it out, but, as I tired, the sweat broke out on my body and chilled into a clammy, ice-cold film, and then the wind cut through my clothing and into my flesh, seeming to blow straight on to my spine. God, it was cold! For miles, it seemed, I walked along by-roads through unmarked snow and there was no traffic. I must have missed the turning back on to the Berlin road, for it was almost midnight when I finally found it again and I saw no transport café — only dark woods and the illimitable miles of white agricultural land, flat and wind-swept.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”