Air Bridge (6)

By:

March 9, 2015

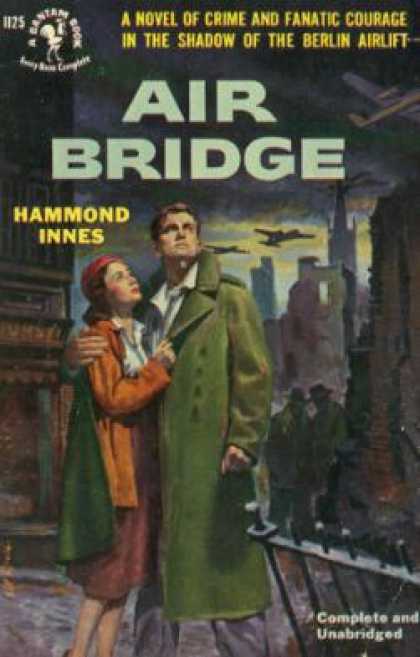

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Hammond Innes’s 1951 espionage thriller/Robinsonade Air Bridge. Set in England during the Berlin blockade and airlift of 1948–49 (during which time the British RAF and other aircrews frustrated the Soviet Union’s attempt to gain practical control of that city), the novel’s protagonist is a mercenary pilot… but is he a traitor? Hammond Innes wrote over 30 adventures, many of them set in hostile natural environments. Enjoy!

Saeton left next morning on the old motor bike which was their sole form of transport. And it was only after he’d gone that I realized how much the whole tempo of the place depended on him. Without the driving enthusiasm of his personality it all seemed flat. Tubby worked with the concentration of a man trying hard to lose himself in what he was making. But it was a negative drive. For myself I found the time hanging slowly on the hands of my watch and I determined to go down to the farm that evening and make it up with Else. Somehow I hadn’t been able to get her out of my mind. I think it was her presence in the hangar with Saeton that first night that I’d arrived at Membury that intrigued me. The obvious explanation I had proved to be wrong. Now, suddenly, I was filled with an urgent desire to get at the truth. Also I was lonely. I suppose any girl would have done — then. But she was the only one available and as soon as Tubby and I knocked off I went down to the Manor.

The kitchen curtains were drawn and when I knocked at the door it wasn’t Else who opened it. A small, gray-haired woman stood framed against the light, a swish of silk at her feet and the scent of jasmine clinging on the air. “I was looking for Else Langen,” I explained awkwardly.

She smiled. “Else is upstairs dressing. Are you from the airdrome? Then you must be Mr. Fraser. Won’t you come in? I am Mrs. Ellwood.” She closed the door behind me. “You must find it very cold up at the airfield now. I really think Mr. Saeton should get some proper heating put in. I’ve told him, any time he or his friends want a little home comfort to come over and see us. But he’s always so busy.” We were in the kitchen now and she went over to the Aga cooker and stirred vigorously at the contents of a saucepan, holding her dressing-gown close around the silk of her dress. “Have you had dinner, Mr. Fraser?”

“No. We have it later —”

“Then why not stay and have some food with us? It’s only stew, but —” She hesitated. “I’m cook tonight. You see, we’re going to the Red Cross dance at Marlborough. It’s for Else, really. Poor child, she’s hardly been anywhere since she came to us. Of course, she’s what they call a D.P. and she’s here as a domestic servant — why do they call them D.P.S? — it’s so depressing. But whether she’s a servant or not, I don’t think it right to keep a young thing shut away here without any life. You people at the airdrome are no help. We never see anything of you. And it is lonely up here. What do you think of Else? Don’t you think she’s pretty, Mr. Fraser?”

“I think she’s very pretty,” I murmured.

She cocked an eye at me. She was like a little gray-haired sparrow and I had a feeling that she missed nothing. “Are you doing anything tonight, Mr. Fraser?”

“No, I was just going to —”

“Then will you do something for me? Will you come to this dance with us? It would be a great kindness. You see, I had arranged for my son, who works with the railways at Swindon, to come over, but this afternoon he rang up to say he had to go to London. I wouldn’t mind if it were an English girl. But you know what country places are. And after all” — she lowered her voice — “she is German. It would be a kindness.”

“But I’ve no clothes,” I murmured.

“Oh!” She waved the spoon at me like a little fairy godmother changing me into evening clothes on the spot. “That’s all right, I’m certain. You’re just about my son’s size. Come along and we’ll see*”

And of course the clothes fitted. It was that sort of a night. By the time I had changed the three of them were assembled in the big lounge hall. Colonel Ellwood was pouring drinks from a decanter that sparkled in the firelight. He was a tall, very erect man with gray hair and a long, serious face. His wife fluttered about with a rustle of silk. And Else sat in a big winged-chair staring into the fire. She was dressed in very deep blue and her face and shoulders were like marble. She looked lonely and a little frightened. She didn’t look up as I came in; She seemed remote, shut away in a world of her own. Only when Mrs. Ellwood called to her did she turn her head. “I think you know Mr. Fraser.” She saw me then and her eyes widened. For an awful moment I thought she was going to run from the room, but then she said, “Good-evening,” in a cold, distant voice and turned back to the fire.

She hardly said a word all through dinner and when we were together in the back of the car she drew away from me and sat huddled in her corner, her face a white blur in the reflected light of the headlights. Not until we were dancing together in the warmth of the ballroom did she break that frigid silence and then I think it was only her sense of loneliness in that alien gathering that made her say, “Why did you come?”

“I was lonely,” I said.

“Lonely?” She looked up at me then. “You have your — friends.”

“I happen to work there — that’s all,” I said.

“But they are your friends.”

“Three weeks ago I had never met any of them.”

She stared at me. “But you are a partner. You put up money.” She hesitated. “Why do you come here if you do not know them?”

“It’s a long story,” I answered and holding her close in the swing of the music I suddenly found myself wanting to tell her. But instead I said, “Else. I want to apologize for the other night. I thought —” I didn’t know how to put it, so I said, “That first night I came to Membury — why were you in the hangar with Saeton?”

Her gray eyes lifted to my face and then to the cut on my forehead. “That also is a long story,” she said slowly. And then in a more friendly tone: “You are a strange person.”

“Why did Saeton think I was a friend of yours that night?” I asked. “Why did he call to me in German?”

She didn’t answer for a moment and I thought she was going to ignore the question. But at length she said, “Perhaps I tell you some day.” We danced in silence for a time. I have said that she was a big girl, but she was incredibly light on her feet She was like thistledown in my arms and yet I could feel the warm strength of her under my hand. The warmth and the music were going to my head, banishing loneliness and the tension of the past weeks. “Why did you come to the farm tonight?” she asked suddenly.

“To see you,” I answered.

“To apologize?” She was smiling for the first time. “You did not have to.”

“I told you — I was lonely.”

“Lonely!” Her face seemed to harden. “You do not know what that word means. Please, I would like a drink.” The music had stopped and I took her over to the bar. “Well, here is to the success of those engines!” Her tone was light, but as she drank her eyes were watching me and they did not smile. “Why do you not drink? You are not so crazy about those engines as Mr. Saeton, eh?” She used the word crazy in its real sense.

“No,” I said.

She nodded. “Of course not. For him they are a part of his nature now — a great millstone round his neck.” She hesitated and then said, “Everyone makes for himself on this earth some particular hell of his own. With Saeton it is these engines, ja?” She looked up into my face again. “When are they finished — when do you fly them?”

I hesitated, but there was no reason why she shouldn’t know. Living so close at the Manor she would see us in the air. “With luck we’ll be in the air by Christmas. Airworthiness tests are fixed for the first week in January.”

“So!” A sudden mood of excitement showed in her eyes. “Then you go on to the air bridge. I hope your friend Saeton is happy then.” Her voice trembled slightly. She was suddenly tense and the excitement in her eyes had changed to bitterness.

“Why are you so interested in Saeton?” I asked her.

“Interested — in Saeton?” She seemed surprised, almost shocked.

“Are you in love with him?” I asked.

Her face hardened and she bit at her lower lip. “What has he been saying?”

“Nothing,” I answered.

“Then why do you ask me if I am in love with him? How can I be in love with a man I hate, a man who has —” She stopped short, staring at me angrily. “Oh!” she exclaimed. “You are so stupid. You do not understand nothing — nothing.” Her fingers were white against the stem of the glass as she sought for words.

“Why do you say you hate him?” I asked.

“Why? Because I offer him the only thing I have left to offer — because I crawl to him like a dog —” Her face was suddenly white with anger. “He only laugh. He laugh in my face, I tell you, as though I am a common — nutte.” She spat the word out as though she were hating herself as well as Saeton. “And then that Carter woman comes. He is a devil,” she whispered and then turned quickly away from me and stared miserably at the crowded bar. “You talk of loneliness! That is what it is to be lonely. Here, with all these people. To be away from one’s own people, a stranger in a —”

“You think I don’t understand,” I said gently. “I was eighteen months in a prison camp in Germany.”

“That is not the same thing. There you are still with your own peoples.”

“Not after I escaped. For three weeks I was alone in Germany, on the run.”

She stared up at me and gave a little sigh. “Then perhaps you do understand. But you are not alone here.”

I hesitated, and then I said, “More alone than I have ever been.”

“More alone ” She stopped and gazed at me unbelievingly. “But why is that?”

I took her arm and guided her to a seat. I had to tell her now. I had to tell someone and she was a German, alone in England — my story was safe with her. I told her the whole thing, sitting there in an alcove near a roaring fire with the sound of dance music in my ears. When I had finished she put her hand on mine. “Why did you tell me?”

I shrugged my shoulders. I didn’t know myself. “Let’s dance,” I said.

We didn’t talk much after that. We just seemed to lose ourselves in the music. And then Mrs. Ellwood came and said we must go as her husband had to start work early the next morning. In the car going back Else didn’t talk, but she no longer shrank into her corner of the seat. Her shoulder leaned against mine and when I closed my hand over hers she didn’t withdraw. “Why are you so silent?” I asked.

“I am thinking of Germany and what fun we could have had there — in the old days. Do you know Weisbaden?”

“Only from the air,” I answered and then wished I had not said that as I saw her lips tighten.

“Yes, of course — from the air.” She took her hand away and seemed to withdraw into herself. She didn’t speak again until the car was climbing the hill to Membury, and then she said very quietly, “Do not come to see me again, Neil.”

“Of course I shall,” I said.

“No.” She said it almost violently, her eyes staring at me out of the darkness. Her hand gripped mine. “Please try to understand. We are like two people who have caught sight of each other for a moment through a crack in the wall that separates us. Whatever the S.S. do to my father, I am still a German. I must hold fast to that, because it is all I have left now. I am German, you are English, and also you are working —” She stopped and her grip on my hand tightened. “I like you too much. Do not to come again, please. It is better so.”

I didn’t know what to say. And then the car stopped. We were at the track leading up to the quarters. “You can return the clothes in the morning,” Mrs. Ellwood said. I got out and thanked them for the evening. As I was about to shut the car door, Else leaned forward. “In England do you not kiss your partners good-night?” Her face was a pale circle in the darkness, her eyes wide. I bent to kiss her cheek, but found her lips instead. “Good-bye,” she whispered.

The Ellwoods were chuckling happily as they drove off. I stood watching until the red tail-light had turned into the Manor drive and then I went up the track to the quarters, wondering about Else.

It was to be nearly three weeks before I saw Else again, for Saeton returned the following evening with the news that the Air Ministry now wanted the plane on the airlift by the 10th January, and airworthiness tests had been fixed for 1st January.

In the days that followed I plumbed the depths of physical exhaustion. I had neither the time nor the energy for anything else. And it went on, day after day, one week dragging into the next with no let-up, no pause. Saeton didn’t drive. He led. He did as long as we did at the bench, then he went back to the hangar, typing letters far into the night, ordering things, staving off creditors, running the whole of the business side of the company. My admiration for the man was boundless, but somehow I had no sympathy for him. I could admire him, but I couldn’t like him. He was inhuman, as impersonal as the mechanism we pieced together. He drove us with the sure touch of a coachman who knew just how to get the last ounce out of his horses, but didn’t care a damn what happened to them in the end so long as he made the next stage on time.

But it was exciting. And it was that sense of excitement that carried me through to Christmas. The airfield hardened to iron as the cold gripped it. The runways gleamed white with frost in the sunshine on fine days. But mostly it was gray and cold with the plowed-up earth black and ringing hard and metallic like solidified lava. There was no heating in the hangar. It had the chill dank smell of a tomb. Only the work kept us warm as we lathered ourselves daily into a sweat of exhaustion.

Saeton was working for engine completion on December 20, installation by December 23 and first test on Christmas Day. It was a tight schedule, but he wanted a clear week for tests. But though we worked far on into the night, we were behind schedule all the time and it was not until Christmas Eve that we completed that second engine.

The final adjustments were made at eight-thirty in the evening. We were dead beat and we stood in front of the gleaming mass of metal in a sort of daze. None of us said a word. We just stood back and looked at it. I produced a packet of cigarettes and tossed one to Saeton. He lit it and drew the smoke into his lungs as though smoke alone could ease the tension of his nerves. “All right, fill her up with oil, Tubby, and switch on the juice. I’ll get Diana. She’d like to be in on this.” He went over to the phone and rang the quarters. I helped fill up with oil. We checked that there was petrol in the wall tank, tightened the unit of the petrol feed and switched on.

There was a tense silence as we waited for Diana. Five weeks’ work stood before us and a touch of the starter button would tell us whether we’d made a job of it. It wasn’t like an engine coming out of a works. There everything moves with an inevitable progression from the foundry and the lathes and the electrical shop to the assembly and the final running in. This was different. Everything had been made by hand. One tiny slip in any of the precision work… I thought of how tired we were. It seemed incredible that everything would work smoothly.

A knock on the door of the hangar sounded incredibly loud in the silence. Tubby went to the door and let his wife in. “Well, there it is, Diana,” Saeton said, pointing to the thing. His voice trembled slightly. “Thought you’d like to see what your cooking has given birth to.” Our laughter was uneasy, forced. “Okay, Tubby. Let her go.” He turned away with a quick nervous twist of his shoulders and walked down to the far end of the bench. He wasn’t going to touch that starter switch himself. He wasn’t even going to watch. He stood with his back towards us, puffing at his cigarette, his hands playing aimlessly with the pieces of metal lying on the bench.

Tubby watched him, hesitating.

“Go on — start it.” Saeton’s voice was a rasp.

Tubby glanced at me, swallowed nervously and crossed to the starter motor which was already connected up. He pressed the switch. If groaned, overloaded with the stiffness of the metal. The groaning sound went on and on. He switched off and went over to the engine, his practiced eye running over it, checking. Then he went back to the starter motor. The groaning sound was faster now, moving to a hum. There was a sharp explosion. The engine rocked. The hum of the starter took over again and then suddenly the stillness of the hangar was shattered by a roar as the motor picked up. The whole building seemed to shake. Tubby switched off, hurried to the engine and adjusted the controls. When he started it again, the roar settled to a steady, glorious hum of power, smooth and even like the dynamos of a power station.

Saeton ground out his cigarette and came back along the bench. His face was shining with sweat. “She’s okay,” he shouted about the din. It was part statement, part question. Tubby looked up from the controls and his fat, friendly face was creased in a happy grin and he nodded. “Carburetion wants a bit of adjustment and the timing on that —”

“To hell with the adjustments,” Saeton shouted. “We’ll do those tomorrow. All I care about at the moment is that she goes. Now switch the damned thing off and let’s go and have a drink. My God, we’ve earned it.”

The roar died away as Tubby cut off the juice. The hangar was suddenly still again. But there was no tension in the stillness now. We were all grinning and slapping each other on the back. Tubby caught hold of his wife and hugged her. She had caught our mood of relief. Her eyes were shining and she just didn’t seem able to contain her excitement “Anybody else like a kiss?” I was nearest to her and she reached up and touched her lips to mine. Then she turned and caught hold of Saeton. She pressed her lips to his, her hands tightening on his overalls. He caught hold of her shoulders and pushed her away almost roughly. “Come on. Let’s get a drink.” His voice was hoarse.

Saeton had kept a bottle of whisky for this moment “Here’s to the airlift!” he said.

“To the airlift!” we echoed.

We drank it neat, talking excitedly of how we’d manage the installation, what the first test flight would show, how the plane would behave on two engines. Saeton planned to use the outboard engines for take-off only. With the extra power developed by the Satan Mark II all flying would be done on the two engines. We bridged in our excitement all the immediate problems and talked instead of how we should develop the company, what planes we should buy, what routes we should operate, whose works we should take over for mass production. In a flash the bottle was empty. Saeton wrung the last drop out of it and smashed it on the concrete floor. “That’s the best bottle of Scotch I’ve ever had and I won’t have it lying on any damned rubbish heap,” he shouted. His eyes were dilated with the drink and his own excitement.

Our glasses suddenly empty, we stood around looking at them in silence. It seemed a pity to end the evening like this. Saeton apparently felt the same. “Look, Tubby,” he said. “Suppose you nip on the old bike and run down into Ramsbury. Bring back a couple of bottles. Doesn’t matter what it costs.” He glanced at me. “Okay, Neil? It’s your money.” And as I nodded, he clapped my arm. “You won’t regret having backed us. If you live to be as old as Methuselah you’ll never make a better investment than this. More Scotch, Tubby!” He waved his arm expansively. “Get on your charger, boy, and ride like hell. This bloody dump is out of Scotch. Come on. Well hold your stirrups for you and we’ll be out to cheer you as you ride back, bottles clanking in your saddle-bags.”

We were all laughing and shouting as we trooped out to the store-room where the bike was housed. Tubby roared off, his face beaming, his hand whacking at the rear of the bike as he flogged through the gears. His tail-light disappeared through the trees and we fell suddenly silent Saeton passed his hand across his eyes. “Let’s go in,” he said moodily and I saw that the nerves at the corners of his eyes were twitching. He was near to breaking point. We all were. A good drunk would do us good and I suddenly thought of Else. “What about making it a party,” I said. “I’ll go down and see the Ellwoods.” I knew they wouldn’t come, but I thought Else might. Saeton tried to stop me, but I was already hurrying down the track and I ignored him.

A light was on over the front door of the farm. It looked friendly and welcoming.

Mrs. Ellwood answered my ring. “It’s you, Mr. Fraser.” She sounded surprised. “We thought you must have left.”

“We’ve been very busy,” I murmured.

“Come in, won’t you?”

“No, thank you. I just came down to say we’re having a party. I wondered if you and Colonel Ellwood could come up for a drink. And Else/’ I added.

Her eyes twinkled. “It’s Else you’re wanting, isn’t it? What a pity! We’ve been expecting you all this time and now you come tonight. Else has had to go to London. Something about her passage. She’s going back to Germany, you know.”

“To Germany?”

“Yes. Oh, dear, it’s all very sudden. And what we shall do without her I don’t know. She’s been such a help.”

“When is she going?” I asked.

“In a few days’ time I imagine. It was all very unexpected. Just after that dance. She got a letter to say her brother was very ill. And now there is some trouble about her papers. Do come and see her before she goes.”

“Yes,” I murmured. “Yes, I’ll come down one evening.” I backed away trying to remember if Else had said she had a second brother. “Good-night, Mrs. Ellwood. Sorry you won’t join us.” I heard the door close as I started back down the drive. Hell! The evening suddenly seemed flat. A feeling of violent anger swept through me. Damn the girl. Why for God’s sake, couldn’t she be home this evening of all evenings?

I took a short cut through the woods. I was just in sight of the quarters when I heard the snap of a twig behind me. I glanced over my shoulder and saw the figure of a man emerging out of the darkness. “Who’s that?” he asked. The voice was Tubby*s.

“Neil,” I said. “Did you get the Scotch?”

For answer I heard the clank of bottle against bottle. “Bloody bike ran out of petrol just up the road.” His voice was thick. He’d either had several at the pub or he’d opened one of the bottles. “What are you doing, looking for fairies?”

“IVe just been down to the farm,” I said.

“Else, eh?” He laughed and slipped his arm through mine.

We went on in silence. A lighted window showed through the trees like a homing beacon. We came out of the woods and there was the interior of the dining-room. Saeton and Diana were there, standing very close together, a bottle on the table and drinks in their hands. “I wonder where they got that?” Tubby murmured. “Come on. We’ll give them a surprise.”

We had almost reached the window when Diana moved. She put down her drink and moved closer to Saeton. Her hand touched his. She was talking. I could hear the murmur of her voice through the glass of the window. Tubby had stopped. Saeton fook his hand away and turned towards the door. She caught hold of him, swinging him round, her head thrown back, laughing at him. The tinkle of her laughter came out to us in the cold of the night air.

Tubby moved forward. He was like a man fa a dream, compelled to go to the window as though drawn there by some magnetic influence. Saeton was standing quite still, looking down at Diana, his hard, leathery face unsoftened, a muscle twitching at the corner of his mouth. Standing there in the darkness facing that lighted window it was like watching a puppet show. “All right. If you want it that way.” Saeton’s voice was harsh. It came to us muffled, but clear. He knocked back his drink, set down the glass and seized hold of her by the arms. She lay back in his grip, her hair hanging loose, her face turned up to him in complete abandon.

Saeton hesitated. There was a bitter set about his mouth. Then he drew her to him. Her arms closed round his neck. Her passion was to me something frightening. I was so conscious all the time of Tubby standing there beside me. It was like watching a scene from a play, feeling it through the senses of a character who had yet to come on. Saeton was fumbling at her dress, his face flushed with drink and quite violent Then suddenly he stiffened. His hands came away from her. “That’s enough, Diana,” he said. “Get me another drink.”

“No, Bill. It’s me you want, not drink. You know you do. Why don’t you —”

But he took hold of her hands and tore them from his neck. “I said get me another drink.”

“Oh God! Don’t you understand, darling.” Her hand touched his face, stroking it, smoothing out the deep-etched lines on either side of the mouth. “You want me. You know you do.”

Tubby didn’t move. And I stood there, transfixed by his immobility.

Saeton’s hands slowly reached out for Diana, closed on her and then gripped hold of her and hurled her from him. She hit the edge of the table and clutched at it. He took two steps forward, standing over her, his head thrust slightly forward. “You little fool!” he said. “Can’t you understand you mean nothing to me. Nothing, do you hear? You’re trying to come between me and something that is bigger than both of us. Well, I’m not going to have everything wrecked.”

“Go on,” she cried. “I know I don’t rate as high as that bloody engine of yours. But you can’t go to bed with an engine. And you can with me. Why don’t you forget it for the moment? You know you want me. You know your whole body’s crying out for —”

“Shut up!”

But she couldn’t shut up. She was laughing at him, goading him. “You never were cut out for a monk. You lie awake at nights thinking about me. Don’t you? And I lie awake thinking about you. Oh, Bill, why don’t you —”

“Shut up!” His voice shook with violence and the veins were standing out on his forehead, hard and knotted.

Her voice dropped to a low murmur of invitation. I could no longer hear the words. But the sense was there in her face, in the way she looked at him. His hands came slowly out, searching for her. Then suddenly he straightened up. His hand opened out and he slapped her across the face — twice, once on each cheek. “I said — shut up! Now get out of here.”

She had staggered back, her hand to her mouth, her face white. She looked as though she were going to cry. Saeton reached out for the bottle. “If you’d had any sense you’d have given me that drink.” His voice was no longer hard. “Next time, pick somebody your own size.” He tucked the bottle under his arm and turned to go. But he hesitated at the door, looking back at her. I think he was going to say something conciliatory. But when he saw the blazing fury in her eyes, his face suddenly hardened again. “If you start any trouble between me and Tubby,” he said slowly, “I’ll break your neck. Do you understand?” He wrenched open the door and disappeared.

A moment later the outer door of the quarters opened and we were spotlighted in the sudden shaft of light. Saeton stopped. “How long have you two been —” He slammed the door. “I hope you enjoyed your rubbernecking. I’m going over to the hangar.” His footsteps rang on the iron-hard earth as his figure merged into the darkness of the woods.

Neither of us moved for a moment. Utter stillness surrounded us, broken only by the muffled sound of Diana’s sobs where she lay across the table, her head buried in her hands amongst the litter of glasses. I felt the chill glass of the bottles as Tubby thrust them into my hands. “Take these over to the hangar,” he said in a strangled voice.

I watched him as he opened the door of the quarters and went inside, walking slowly, almost unwillingly. I didn’t move for a moment. I seemed rooted to the spot. Then the door of the dining-room opened and I saw him enter. I’d no desire to stand in as audience on another painful scene. I turned quickly and hurried through the woods after Saeton.

When I entered the hangar, Saeton was sitting on the work bench staring at the new engine and drinking out of the bottle. “Come in, Neil.” He waved the bottle at me. “Have a drink.” His voice was slurred, almost unrecognizable. God knows how much he’d drunk in the short time it had taken me to get to the hangar.

I took the bottle from him. It was brandy and more than half-empty. The liquid ran like fire down my throat and I gasped.

“You saw the whole thing, I suppose?” he asked.

I nodded.

He laughed, a wild, unnatural sound. “What will Tubby do?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

He got off the bench and began pacing up and down. “Why did he ever let her come here? It was no place for her. She likes plenty going on— lots of people, excitement, plenty of noise and movement. Why don’t men learn to understand their wives? Let’s forget about it” He waved his arm angrily. “What have you got there — Scotch?” He came over and picked up one of the bottles from the bench where I’d placed it. “Thank God we’ve got some liquor, anyway.” He glanced at the bottle of brandy which I still held. “Queer, a woman hiding away a bottle like that.” He unscrewed the top of a whisky bottle.

“Haven’t you had enough?” I suggested.

He gave me a glassy stare. “It’s Christmas Eve, isn’t it? And the engine is finished. I could drink a bloody vat.” He raised the bottle to his lips and drank, rocking slightly back on to his heels and then forward on to his toes. “Funny, isn’t it?” he muttered hoarsely, wiping his lips with the back of his hand. “You start out with the idea of celebrating and before you know where you are you’re trying to drown your sorrows. Neil, old man.” His free hand reached out and fastened around my shoulders. ‘Tell me something. Be honest with me now. I want an honest reply. Do you like me?”

I hesitated. If I’d been as drunk as he was it wouldn’t have mattered. But I was comparatively sober and he knew it.

His arm slipped away from my shoulders and he staggered away from me towards the engine. He stood in front of it and addressed it. “You bastard!” he said. Then he lurched round towards me. “I haven’t a friend in the world,” he said and there was a frightful bitterness in his voice which caught on a sob of self-pity. “Not a friend in the whole wide world,” he repeated. “Diana was right. An engine is something you create, not a living being. God damn it! I don’t care. Do you hear me — I don’t care. I don’t give a damn for the whole human race. If they don’t like me, why should I care? I don’t need anything from them. I’m building something of my own. And that’s all I care about, do you hear? I don’t give a damn —” He turned suddenly at the sound of the hangar door opening.

It was Tubby. He came slowly down the hangar. “Give me a drink,” he said.

Saeton handed him the bottle. Tubby raised it to his lips and gulped, Saeton watching him, his body tense. “Well?” he asked. And then as Tubby didn’t answer he added, “For God’s sake say something, can’t you. What happened?”

Tubby raised his eyes and looked at Saeton. But I don’t think he saw him. His hand strayed to the leather belt that supported his trousers. “I thrashed her,” he said in the same flat tone. “She’s packing now.”

“Packing?” Saeton’s voice was suddenly hard and crisp. In that moment he seemed to shake off all the effects of the drink.

“I’ve telephoned for a taxi.”

Saeton strode over to him and caught hold of him by his jacket. “You can’t walk out on me now, Tubby. In a few days we’ll be making our first test flight. After all this time.”

“Can’t you forget about your engine for just one night?” Tubby’s voice was tired. There was a sort of hopelessness about it. “I want some money, Saeton. That’s what I came to see you about.”

Saeton laughed suddenly. ‘There isn’t any money. You know that. Not until we’re on the airlift.” The sudden sense of domination was back in his voice and I knew that he had seen how he could keep Carter with us.

“How much do you want, Tubby?” I asked, feeling for my wallet.

Saeton rounded on me, his face heavy with anger. “If you think the two of us can get the plane into the air, you’re crazy,” he said. “For one thing the margin of time is too small. For another there may be alterations to make. Neither you nor I —” He turned away with a quick, angry shrug.

“How much do you want?” I asked again.

“A fiver.” He came across to me and I gave him the notes. “I hate to do this, Neil, but…” His voice tailed away.

“Forget it,” I said. “Are you sure that will be enough?”

He nodded. “It’s only to get Diana to London. She’ll stay with her friends. She’s got a job waiting for her. It’s just to see her through for a few days. She’s going back to the Malcolm Club. She worked for them during the war and they’ve been wanting her back ever since the airlift got under way.” He stuffed the money into his pocket. “She’ll pay you back.”

He turned to leave the hangar, but Saeton stopped him. “They employ girls at the Malcolm Club, not engineers. What are you going to do?”

Tubby looked at him. “I’m staying here,” he said. “I promised I’d see you into the air and I’ll keep my prom ise. After that —”

But Saeton wasn’t listening. He came across the hangar like a man who has been reprieved. His eyes were alight with excitement, his whole face transfigured. “Then it’s okay. You’re not walking out on me.” He caught hold of Tubby’s hand and wrung it. “Then everything’s all right.”

“Yes,” Tubby answered, withdrawing his hand. “Everything’s all right, Bill.” But as he turned away I saw there were tears in his eyes.

Saeton stood for a moment, watching him go. Then he turned to me. “Come on, Neil. Let’s have a drink.” He seized hold of the opened bottle of Scotch. “Here’s to the test flight!”

There was only room for one thing in the man’s mind. With a sick feeling I turned away. “I’m going to bed,” I said.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”