The Fugitives (16)

By:

August 30, 2014

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Morley Roberts’s 1900 novel The Fugitives, an adventure set against the backdrop of the Second Boer War (1899–1902). The author was once known for his novel The Private Life of Henry Maitland (1912), but he quickly passed into obscurity. How obscure? In a 1966 story about plagiarism (“The Longest Science-Fiction Story Ever Told”), Arthur C. Clarke attributed an 1898 sci-fi story of Roberts’s (“The Anticipator”) about the same topic to H.G. Wells; in a 1967 guest editorial in If (“Herbert George Morley Roberts Wells, Esq.”), a contrite Clarke noted that not a single Morley fan had emerged to point out this error. HiLoBooks — in conjunction with the Save the Adventure book club, which under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn is issuing The Fugitives as an e-book — is rectifying this situation. Enjoy!

That night they ran out of food, and Hardy risked his liberty, to say nothing of his life, which just then appeared of little worth, in stealing something to eat from a neighboring farm. As it turned out, there was no one in the house, which lay all by itself in a little irrigated hollow. He ransacked it and discovered some tinned beef and about four pounds of weevily flour in the bottom of a sack. The whole proceeding was perfectly natural and normal to him, and was in no way a violation of any law. By now he and Blake had reverted to a strange state of nature, that nature which is only about three meals away from the President of any poverty-defence league, which is pretty to think of when some fat men make speeches.

But Hardy did not think of this. Nor did Blake. They were savages by now; grimed, sunburnt, ragged savages, and there was no such thing as law and order or property in the scheme of their universe. Nor, indeed, was there any sense of time; except that the days were atrociously long and the nights peculiarly short even for summer. During that night to the north of Krugersdorp they would have been puzzled to declare how many days they had been on the road. The whole wide world was a phantasmagoria: they themselves were the sole realities in it; the Boers and the war and the British army were shadows dancing on the veldt beyond the horizon; and when Hardy, who had eyes like a hawk, that hunger made clearer, discerned a gun set upon a truck far away on the line, it was just a gun and nothing else. It had no wide implications: to such a degree had their horizons narrowed.

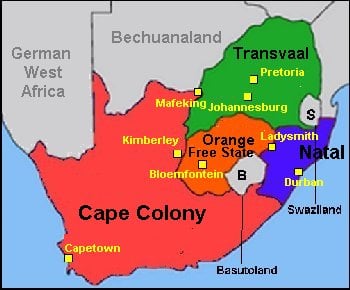

They had to escape. That was the first thing. And then they had to get, let us say, to Kimberley or south of it, by slipping through the line of Boers. But first they had to get to the Vaal. Then once more time narrowed, and with it space. If they could only crawl upon that train, now visibly making up for Potchefstroom, it would seem like final achievement.

Even the Boers ceased to be Boers. They became just so many obstacles. A burglar comes at last to look thus on the police and all other barriers which stand between him and so much plate.

But the oddest thing about this short-sighted life was its forgetfulness and its quick adaptation to necessary misery. They forgot the days and could not calculate time to come. Pretoria was a century off. But so was the Hennop’s River, where they had that particularly fine drink which stood out in serried days of dusty thirst. And so was Krugersdorp when they slunk upon the train and got beneath a tarpaulin that concealed a gun. They lay there for an hour, which was a great portion of eternity. But when the train moved, they forget they had had to wait at all, and they talked, as they spat dust, of indifferent things in the manner of confirmed tramps who are given to talking in a reminiscent manner as if they had had several incarnations of which they retained the memory. But things lost their true relations and were seen in the flat, like a Chinese landscape without perspective. Gordon Hardy told Blake how he happened to know Hoffman, who had introduced him to the Mischief-Maker at Brussels. But Hoffman, Leyds, and Silvio Da Costa were equally misty, though Hardy repeated trivialities about them till Blake was tired. In unconscious revenge he talked about Natal, which appeared as far off as a Saturnian country, and Hardy said “Oh!” and “Ah!” with a strained indifference that Blake did not observe. For he was sure it must be singularly interesting.

They could not risk going through Potchefstroom by daylight, so they got off before the train reached the town and lay all day in a culvert which was exactly like the one that had sheltered Hardy on his way to Pretoria. They were again short of food, for the jolting of the truck over the badly ballasted road had sifted most of their remaining flour away, and left nothing but a few active weevils. Though a sprinkling of weevils in cooked bread makes it look like caraway cake, as a whole diet they are useless, as Hardy remarked when he shook them out. When it got dark they went west-southwest past Potchefstroom and again struck the railway line toward Klerksdorp.

“We’ll have to get food to-morrow,” said Hardy. But the necessity of getting it did not worry him. He pointed out to Blake that no man was much good who could not walk three days on tobacco and water. “And besides we are not hungry now. I remember ——” And he beguiled the way with the story of a friend of his who had been six days without food.

“So when I say we’ll have to get food,” he added, “I mean it will be all the better if we do. That’s all.”

And Blake said “Yes” without any marked enthusiasm at a prospect of a failure in the commissariat. But he was beginning to trust Hardy rather blindly. When any number of men are together, one does all the leading and most of the work. Now Hardy did it, of course.

“I suppose this is adventure,” said Blake, as they walked.

“Don’t doubt it,” replied Hardy, cursing as he fell over a thorn-bush; “only it happens to be real adventure, not romance.”

But he added a moment later, and half to himself, — “Romance comes after.”

Not yet could they look upon their toil with such friendly eyes as to discern its romantic side.

They camped that morning on the banks of the Vaal in a tangle of reeds and willows, where they ventured to light a fire in order to make some coffee. The country was peculiarly deserted, even for a country which is so sparsely populated: they saw no sign of human life, and by bad luck came close to no farm-house which might have offered some opportunity for loot. They ate the last remains of their bacon and washed it down with strong coffee.

“Make up your mind to go hungry for a bit,” said Hardy, as he sat by the slow-moving waters of the river. “At any rate we have plenty of water.”

“It’s the great difficulty of the campaign,” said Blake, who was lying flat on his back looking up at the sky. “I wonder what is going on at Kimberley. Were they hard pressed?”

“Yes,” replied Hardy, with unaffected indifference. These were far-off matters that scarcely troubled him.

“I suppose the new Commander-in-Chief will move there first,” said Blake after a pause. “He should be there or thereabouts now.”

A little interest in the real affairs of men roused itself in him.

“Lend me your map,” he said, and without a word Hardy threw it across to him. Blake rolled over, and, instead of being a tramp, brightened a bit and became a soldier again. He studied the map carefully.

“How far down the river would you go?” he asked after ten minutes.

“Oh, I don’t know, as far as you like,” said Hardy carelessly.

“Humph!” was Blake’s reply, and he sat up and grew suddenly keen. “No further than Christiania, I say.”

“Why not?”

And Blake explained.

“After all the ructions about our going into Natal, Bobs will strike at Bloemfontein for sure. And if Kimberley is so hard pressed he will move on a line which will threaten Bloemfontein and relieve Kimberley at once, don’t you think?”

“I’m not a strategist,” said Hardy. “I’ll take your word for it.”

“I don’t ask you to be a strategist,” replied Blake, “but that is common sense, isn’t it?”

“Sounds like it,” said Hardy, yawning.

“Then we must take it for granted that he will not move direct on Kimberley, for that would make the Boers’ retreat easy. He will strike for the upper Modder. He will be in force and will either compel the Boers to retreat in a hurry or will break their centre and divide them. They must retreat north to Warrenton or to Kimberley, but not north across the veldt. Do you follow?”

Hardy began to get interested.

“Yes, and what then?”

“It will be dangerous for us to follow the Vaal down very far, whether they are retreating or not. The weakest part of them will be south of Hoopstadt or Christiania. We must go south from there.”

“And leave the water?”

If Blake had not been full to the lips of coffee he might have replied differently. But just now he was not thirsty.

“I guess we must. You see our men might be as far as Boshof or further when we get down there. I expect they are fighting now. What date is it?”

“Lord knows,” said Hardy, “somewhere in the beginning of February. I believe it was the second when you climbed that wall. But I hope you are right. We might get to Hoopstadt in three days or so, and Boshof isn’t much more than sixty miles further. I wish we could steal some horses. As it is, I’m beginning to feel that there are neither Boers nor British in our world, but that we have clean dropped out of everything into a dream.”

This was the first consecutive and human conversation they had held since leaving Pretoria, and it did both good and sharpened their tired and blunted minds. Without their quite knowing it, the fact that they were close to water relieved them of such anxiety that the tension relaxed of itself. They were possessed of the first great necessity of existence. And by and by the slow, insistent, onward movement of the great stream, which was then no more than half full, put a new idea into Hardy’s mind.

“I wonder ——” he said.

“What?” asked Blake.

“Nothing,” said Hardy. But all the same he did wonder.

“The river isn’t navigable,” he said, as they issued from their hiding-place when the night fell; “but where there is a river there should be a boat, eh?”

“Yes,” said Blake.

“Why shouldn’t we find one and go down stream in it? It would be better than stumbling over rocks and thorn scrub,” said Hardy. “My legs are in tatters.”

“So are mine,” replied Blake ruefully. “There’s a deal more scratch than skin to mine. But if we took one, supposing we found it, wouldn’t the owners come to look it up?”

“Then we might be had, eh?”

But all the same, Hardy kept his eyes open as long as they stayed on the banks of the stream. That, however, was not long, for the going was very difficult, and they presently struck north for the road and travelled on it at a great rate till nearly dawn.

“I’m getting hungry,” said Blake.

But Hardy replied callously:

“Chew some tobacco.”

He had been doing it himself, although the loose, rough Boer tobacco was not adapted for the habit which so many men who lead hard lives fall into.

But Blake failed when he tried.

“I don’t see that being very ill is a good substitute for being hungry,” he remarked in disgust.

“Oh, stick it out,” said Hardy. “Perhaps we’ll find something to eat by and by.”

And just before the dawn, as they were again striking south, they stumbled on an old trek ox turned out to pick up if he could and to die if he could not.

“Well, it was like murder,” said Blake.

But if it was, they now had food for any reasonable length of time. Hardy spent the morning slicing the hard beef into thin strips, which he laid on the hot rocks to frizzle and dry in the sun. Having beef and water set Blake at ease, and yet he began growling for bread and mustard. Hardy was so much better tempered that he heard him most patiently.

“Don’t grouse so,” he laughed; “you’ve no notion what a low-down wreck you look, Blake, or you would see that water and biltong are quite good enough for you.”

But Blake replied:

“If I can’t see myself, I see you.”

And so the day passed, and the next, and after it another, and still the world was the same, and the same hot sun searched them through even as the cool night winds made them shiver. Only once in the three days did they see a white man, and he was a very old Boer riding down the road toward McDermont as they lay hidden in the spruit that passes that place. Once or twice they saw Kaffirs in the distance, but as they avoided every farm they ran little risk in a country that was practically denuded of all its male white inhabitants. And now they came down on the river once more just where another stream ran into it from the southeast.

“It’s the Vet,” said Hardy. “We had better cross.”

They looked for a pont and at last found it. But close to it was a house in which they saw lights.

“We must swim,” said Hardy.

And Blake confessed he could not swim.

“Well, you are a man,” cried Gordon Hardy, who was much annoyed at so absurd an obstacle. “Why the devil didn’t you say so before?”

This seemed very unjust to Blake, and he demanded hotly why he should have said it before.

“Oh, well, then,” said Hardy, “we’ll try the pont. Don’t argue!”

“I wasn’t arguing,” retorted Blake. “Of all the absurd chaps ——”

“Rot,” said Hardy crossly, “you are arguing. Of course any man ought to be able to swim.”

Blake held his tongue. If he did it with difficulty, that difficulty is not hard to understand. Hardy was certainly exigent.

It was long past midnight before they dared go down to the water’s edge and get upon the pont. As they pulled the heavy thing across, the chain creaked and rattled, as Hardy expressed it, “enough to wake the dead.”

But there were many dead that day to the south of them that would not wake till the day of judgment, and just as they camped south of Hoopstadt, in the willows fringing the Vet, Blake seemed to know it.

“I hear something,” he said uneasily.

“Perhaps you hear the sun getting up,” cried Hardy, who had recovered his good temper.

“I wonder ——”

“What do you wonder, Blake?”

But Blake did not answer. He left Hardy and went out on the open veldt and lay down. Hardy followed him curiously.

“What are you doing?”

Blake lifted his hand impatiently, and Hardy sank on his heels in a favorite Kaffir attitude.

“How many miles do you suppose ——” began Blake, and then he stopped. “By God, I hear guns!” he said.

* “I suppose this is adventure,” said Blake, as they walked. “Don’t doubt it,” replied Hardy, cursing as he fell over a thorn-bush; “only it happens to be real adventure, not romance.” But he added a moment later, and half to himself, — “Romance comes after.” — A concise statement of a certain era’s attitude towards adventure.

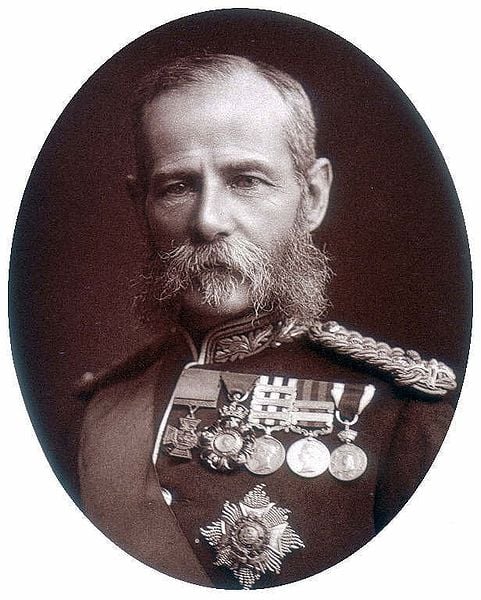

* “After all the ructions about our going into Natal, Bobs will strike at Bloemfontein for sure. And if Kimberley is so hard pressed he will move on a line which will threaten Bloemfontein and relieve Kimberley at once, don’t you think?” — “Bobs” was the popular nickname for Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, one of the most successful British commanders of the 19th century. He served in the Indian rebellion, the Expedition to Abyssinia and the Second Anglo-Afghan War before leading British Forces to success in the Second Boer War. He also became the last Commander-in-Chief of the Forces before the post was abolished in 1904.

* They looked for a pont and at last found it. — Afrikaans for “ferry.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”