Goslings (22)

By:

May 3, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twenty-second installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

A third factor that had contributed to the perfection of that complete understanding was not realized by either until they were descending the hill into Bisham.

“I rather wish we weren’t going back,” said Eileen. “Let’s stop a moment. I want to talk. We’ve never thought of what we’re going to do.”

“Do?” said Jasper, as he dismounted. “Well, we’ve just got to make an announcement and that’s the end of it. The Jenkyns lot have all gone.”

“It isn’t the end, it’s the beginning,” replied Eileen. “Don’t you see that we can’t even explain?”

“We sha’n’t try.”

“We shall. We shall have to — in a way. It’ll take years and years to do it. But the point is that they won’t understand, now, none of them, not even Elsie Durham. We aren’t free any longer.”

“We aren’t alone,” she added, bringing the hitherto unacknowledged factor into prominence.

Thrale frowned and looked up into the thin brightness of the frosty sky. “Yes, I understand,” he said. “It’s public opinion that compels one to regard love as shameful and secret. Alone together, free from every suspicion, we hadn’t a doubt. But now, we have to explain and we can’t explain, and we are forced against our wills to wonder whether we can be right and all the rest of the world wrong.”

“We are right,” put in Eileen.

“Only we can’t prove it to anyone but ourselves.”

“And we shouldn’t want to, if we hadn’t got to live with them.”

For a moment they looked at one another thoughtfully.

“No, we mustn’t run away,” Jasper said, with determination, after a pause. “Look, the flood has begun to go down already. That’s our work. There’s other work for us to do yet.”

For a time they were silent, looking down on to Marlow and out over the valley.

“We didn’t go over that hill,” said Eileen, at last, pointing to the distant rise of Handy Cross.

“No,” replied Jasper, and then, “we won’t hide behind hills. Damn public opinion.”

“Oh, yes, damn public opinion,” agreed Eileen. “But we won’t stay in Marlow always.”

THE TERRORS OF SPRING

1

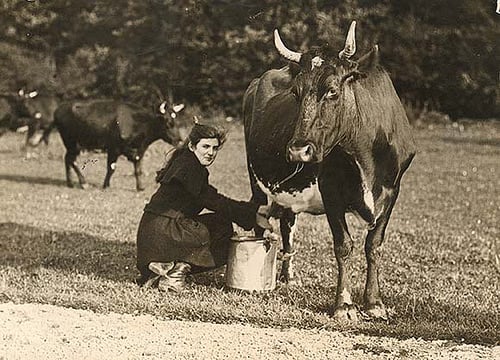

The frost gave way on the third night, and for ten days there was a spell of mild weather with some rain. Carrie Oliver began to contemplate the possibility of getting forward with such ploughing as still remained to be done. She proposed to have an increased acreage of arable that year, and less pasture, less hay and less turnips; the arable was to include potatoes, beans and peas. For the community was rapidly tending towards vegetarianism. They had no butcher in Marlow, and the women revolted against the slaughter of cattle and sheep. They were hesitating and clumsy in the attack, and so inflicted wounds which were not fatal, they turned sick at the sight of the brute’s agonies and at the appalling spurts of blood, and finally when the animal was at last mercifully dead, they bungled the dissection of the carcase.

“I’d sooner starve than do it again,” was the invariable decision pronounced by any new volunteer who had heroically offered to provide Marlow with meat, and even Carrie Oliver admitted that it was a “beastly dirty job.”

“Only,” she added “we’ll ’ave to go on breeding calves or we won’t get no milk, an’ what are we goin’ to do with the bullocks?”

The committee wondered if some form of barter might not be introduced. Wycombe and Henley might have something to offer in exchange, or, failing that, might be urged to accept these superfluous beasts as a present, returning the skins and horns, for which there might be a use in the near future. Sheep must be reared for their wool — the clothes of the community would not last for ever. The subjects of tanning and weaving were being studied by certain members of the now enlarged committee. Neither operation presented insuperable difficulties.

Now that a certain supply of food was provided for, the community was already turning its energy towards the industries. Many schemes were being planned and debated. Marlow was well situated, with such abundance of water and wood at its gates; and the question of attracting desirable immigrants had been raised.

Time was afforded for the consideration of all these schemes by the great frost which began on New Year’s Day and lasted until the end of February.

The frost came first from the south-west, and for three days the country was changed into a fairy world built of sharp white crystals, a world that was seen dimly through a magic veil of mist. Then followed a black and bitter wind from the north-east, that bought a thin and driving snow, and when the wind fell the country was locked in an iron shell that was not relaxed for six weeks.

The flood had nearly subsided before the first frost came, but the river was still high, and presently the water came down laden with ice-floes, that jammed against the weir and the mill, and formed a sheet of ice that gradually crept back towards the bridge.

All field and mill work was stopped, and Thrale and Eileen spent two or three days a week making excursions to London, bringing back coal and other forms of riches.

Their fear of being misunderstood had proved to have been an exaggeration. In that exalted mood of theirs, which had risen to such heights, after four days of adventurous solitude, they had come a little too near the stars. In finding themselves they had lost touch with the world.

Elsie Durham had smiled at their defensive announcement.

“My dear children,” she had said, “don’t be touchy about it. I am so glad; and, of course, I’ve known for months that you would come to an understanding. And there’s no need to tell me that your — agreement, did you say?— was entirely different to any other. I know. But be human about it. Don’t apologize for it by being superior to all of us.”

“Oh, you’re a dear,” Eileen had said enthusiastically.

Nevertheless there were many women still left in Marlow who were less spiritually-minded than Elsie Durham. Comparative idleness induced gossip, and there was more than one party in the community which regarded Thrale and Eileen with disfavour.

The old ruts had been worn too deep to be smoothed out in a few months, however heavy had been the great roller of necessity. And, strangely enough, the life of Sam Evans at High Wycombe was regarded by many of the more bigoted with less displeasure than this perfectly wholesome and desirable union of Thrale and Eileen. The prostitution of Sam Evans was a new thing outside the experience of these women, and it was accepted as an outcome of the new conditions. The other affair was familiar in its associations, and was condemned on both the old and the new precedents.

The mass of the women were quite unable to think out a new morality for themselves….

Relief from all these foolish criticisms, gossipings and false emotions came when the frost broke. A warm rain in the first week of March released the soil from its bonds, and as the retarded spring began to move impatiently into life there was a great call for labour.

But as the year ripened the temperament of the community exhibited a new and alarming symptom.

There was a terrible spirit of depression abroad.

All Nature was warm with the movement of reproduction. Nature was growing and propagating, thrusting out and taking a larger hold upon life. Nature was coming to the fight with new reserves and allies, a fruitful and increasing army, eager for the struggle against this little decreasing band of sterile humanity. Nature was prolific and these women were barren.

And in some inexplicable way the consciousness of futility had spread through the Marlow community. Some posthumous children had been born since the plague, a few young girls —Millie among them — were pregnant, but death had been busier than life during the winter, and from outside came stray reports that in other communities death had been busier still.

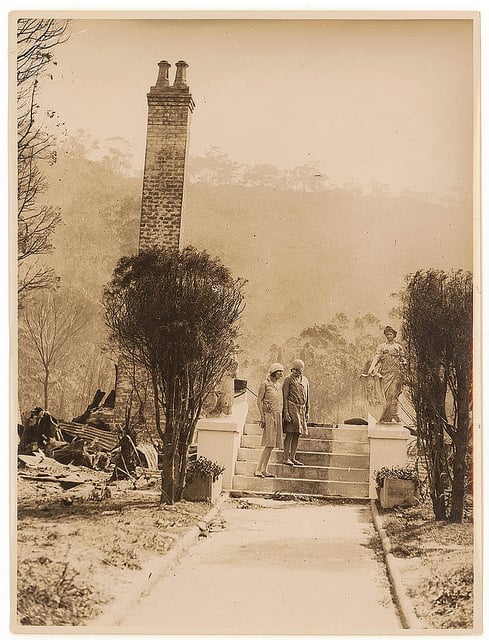

What hope was there for that generation? They were too few to cope with their task. Grass was growing in their streets, their houses were in need of repair, and after their day’s labour in the fields to provide themselves with food, they had neither strength nor inclination to take up the battle anew.

Moreover, the spice was gone from life. Some inherent need for emulation was gone. They were ceasing to take any pride in their persons, and in their clothes. They wore knickerbockers or trousers for convenience in working, and suffered a strange loss of self-esteem in consequence. Many of the younger women still returned in the evenings to what skirts and ribbons they still possessed, but the habit was declining. The uselessness of it was growing even more apparent. There were no sex distinctions or class distinctions among them. Of what account was it that one girl was prettier or better dressed than her neighbour? What mattered was whether she was a stronger or more intelligent worker.

Above all, the woman’s need for love and admiration could find no outlet. They realized that they were becoming hardened and unsexed, and revolted against the coming change. Something within them rose up and cried for expression, and when it was thwarted it turned to a thing of evil….

The mind of the community was becoming distorted. Hysteria, sexual perversions, and various forms of religious mania were rife. Young women broke into futile and unsatisfying orgies of foolish dancing, and middle-aged women became absorbed in the contemplation of a male and human god.

Even the committee did not escape the influence of the growing despair. They looked forward to a future when such machines and tools as they possessed would be worn out, and they had no means of replacing them.

Thrale had reported that the line to London was becoming unsafe for the passage of his trucks. Rust was at work upon the rails; rain and floods had weakened embankments; young growths were springing up on the permanent way, and it was hopeless to contemplate any work of repair. In the old days an army of men had been needed for that work alone. The country roads needed re-metalling, and the houses restoration; they had not the means or the labour to undertake half the necessary work. There were breaches in the river bank and a large and apparently permanent lake was forming in the low meadows towards Bourne End. All about them Nature was so intensely busy in her own regardless way, and they were helpless, now, to oppose her.

The age of iron and machinery was falling into a swift decline. All that the community could look for in the future was a return to primitive conditions and the fight for bare life. Every year their tools and machines would grow less efficient, every year Nature would return more powerful to the attack. In ten years they would be fighting her with rude and tedious weapons of wood, grinding their scanty corn between two stones, and living from hand to mouth. In the bountiful South such a life might have its rewards, but how could they endure it in this uncertain and cruel North?

So while the sun rose higher in the sky and the earth was wonderfully reclothed, the women of Marlow fell deeper and deeper into the horrors of mental depression. What had they to work for, and to hope for, save this miserable possession of unsatisfied life?

SMOKE

1

One bright morning, at the end of April, Jasper and Eileen sat on the cliffs at the Land’s End and talked of the future.

Ten days before, they had left Marlow on bicycles to make exploration. They intended to return; they had explained they would be away for a month at the outside, but in view of the growing depression and the loss of spirit shown by the community, they considered it necessary to go out and discover what conditions obtained in other parts of England. It might be, they urged, that the plague had been less deadly in other districts.

“We should not know, here,” Jasper had argued. “There may be many men left elsewhere; but they might not have been able to communicate with us yet. Their attention, like ours, would have been concentrated upon local conditions for a time. Eileen and I will find out. Perhaps we may be able to open up communication again. In any case we’ll come back within a month and report.”

His natural instinct had taken him into the West Country.

They had left Elsie Durham slightly more cheerful. They had given her a gleam of hope, given her something, at last, to which she might look forward.

Their own hopes had quickly faded and died as they rode on into the West. By the time they reached Plymouth they were thinking of Marlow as a place peculiarly favoured by Providence.

At first they had passed through communities conducted on lines resembling their own, greater or smaller groups of women working more or less in co-operation. In many of these communities a single man was living — in some cases two men — who viewed their duty towards society in the same light as the Adonis of Wycombe. But the unit grew steadily smaller as they progressed. It was no longer the town or village community but the farm which was the centre of activity, and the occupied farms grew more scattered. For it appeared that here in the West the plague had attacked women as well as men. Another curious fact they learned was that the men had taken longer to die. One woman spoke of having nursed her husband for two months before the paralysis proved fatal….

And if the depression in Marlow had been great, the travellers soon learned that elsewhere it was greater still. The women worked mechanically, drudgingly. They spoke in low, melancholy voices when they were questioned, and save for a faint accession of interest in Thrale’s presence there, and the signs of some feeble flicker of hope as they asked of conditions further north and east, they appeared to have no thought beyond the instant necessity of sustaining the life to which they clung so feebly.

Thrale and Eileen rode on into Cornwall, not because they still hoped, but because they both felt a vivid desire to reach the Land’s End and gaze out over the Atlantic. They wanted to leave this desolate land behind them for a few hours, and rest their minds in the presence of the unchangeable sea.

“Let us go on and forget for a few days,” Eileen had said, and so they had at last reached the furthest limit of land.

Cornwall had proved to be a land of the dead. Save for a few women in the neighbourhood of St Austell, they had not seen a living human being in the whole county.

And so, on this clear April morning, they sat upon this ultimate cliff and talked of the future.

The water below them was delicately flecked with white. No long rollers were riding in from the Atlantic, but the fresh April breeze was flicking the crests of little waves into foam; and, above, an ever-renewed drift of scattered white clouds threw coursing shadows upon the blues and purples of the curdling sea.

Eileen and Thrale had walked southwards as far as Carn Voel to avoid the obstruction to vision of the Longships, and on three sides they looked out to an unbroken horizon of water, which on that bright morning was clearly differentiated from the impending sky.

“One might forget here,” remarked Eileen, after a long silence.

“If it were better to forget,” said Jasper.

Eileen drew up her knees until she could rest her chin upon them, embracing them with her arms. “What can one do?” she asked. “What good is it all, if there is no future?”

“Just to live out one’s own life in the best way,” was the answer.

She frowned over that for a time. “Do you really believe, dear,” she said, when she had considered Jasper’s suggestion, “do you really believe that this is the end of humanity?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I have changed my mind half a dozen times in the last few days. There may be a race untouched somewhere in the archipelagos of the South Seas, perhaps — which will gradually develop and repeople the world again.”

“Or in Australia, or New Zealand,” she prompted.

“We should have heard from them before this,” he said. “We must have heard before this.”

“And is there no hope for us, here in England, in Marlow? There are a few boys — infants born since the plague, you know — and there will be more children in the future —Evans’s children and those others. There were two men in some places, you remember.”

“Can they ever grow up? It seems to me that the women are dying. They’ve nothing to live for. It’s only a year since the plague first came, and look at them now. What will they be like in five years’ time? They’ll die of hopelessness, or commit suicide, or simply starve from the lack of any purpose in living, because work isn’t worth while. And the others, the mothers, that have some object in living, will fall back into savagery. They’ll be so occupied in the necessity for work, for forcing a living out of the ground somehow, that they’ll have neither time nor wish to teach their children. I don’t know, but it seems to me that we are faced with decrease, gradually leading on to extinction.

“And I doubt,” he continued, after a little hesitation, “I doubt whether these sons of the new conditions will have much vitality. They are the children of lust on the father’s side, worse still, of tired lust. It does make a difference. Perhaps if we were a young and vigorous people like the old Jews the seed would be strong enough to override any inherent weakness. But we are not, we are an old civilization. Before the plague, we had come to a consideration of eugenics. It had been forced upon us. A vital and growing people does not spend its time on such a question as that. Eugenics was a proposition that grew out of the necessity of the time. It was easy enough to deny decadence, and to prove our fitness by apparently sound argument, but, to me, it always seemed that this growing demand for some form of artificial selection of parents, by restriction of the palpably unfit, afforded the surest evidence. Things like that are only produced if there is a need for them. Eugenics was a symptom.”

Eileen sighed. “And what about us?” she asked.

“We’re happy,” replied Jasper. “Probably the happiest people in the world at the present time. And we must try to give some of our happiness to others. We must go back to Marlow and work for the community. And I think we’ll try in our limited way to do something for the younger generation. Perhaps, it might be possible for us to go north and try our hands at making steel, there are probably women there who would help us. But I don’t think it’s worth while, unless to preserve our knowledge and hand it on. We can only lessen the difficulty in one little district for a time. As the pressure of necessity grows, as it must grow, we shall be forced to abandon manufacture. The need for food will outrun us. We are too few, and it will be simpler and perhaps quicker to plough with a wooden plough than to wait for our faulty and slowly-produced steel. The adult population, small as it is, must decrease, and I’m afraid it will decrease more rapidly than we anticipate, owing to these causes of depression and lack of stimulus….”

“Oh, well,” said Eileen at last, getting to her feet, “we’re happy, as you say, and our job seems pretty plain before us. To-morrow, I suppose, we ought to be getting back, though I hate taking the news to Elsie.”

Jasper came and stood beside her, and put his arm across her shoulders. “We, at any rate, must keep our spirits up,” he said. “That, before everything.”

“I’m all right,” said Eileen, brightly. “I’ve got you and, for the moment, the sea. We’ll come back here sometimes, if the roads don’t get too bad.”

“Yes, if the roads don’t get too bad.”

“And, already, the briars are creeping across the road from hedge to hedge. The forest is coming back.”

“The forest and the wild.”

He drew her a little closer and they stood looking out towards the horizon.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”