Goslings (6)

By:

October 12, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the sixth installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

3

Thrale’s “higher forces” had shown their hand.

The humble and rotund instrument of their choice had served his purpose, and he was probably the first man in London to receive the news — a delicate acknowledgment, perhaps, of his services.

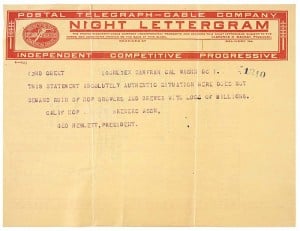

The telegram was addressed to the firm, but as neither of the heads of the house had arrived, Gosling opened it according to precedent.

“Gosh!” was his sole exclamation, but the tone of it stirred the interest of Flack, who turned to see his colleague’s rather protuberant blue eyes staring with a fishy glare at a flimsy sheet of paper which visibly trembled in the hold of two clusters of fat fingers.

Flack lifted his spectacles and holding them on a level with his eyebrows, said, “Bad news?”

Gosling sat down, and in the fever of the moment wiped his forehead with his snuff handkerchief, then discovered his mistake and laid the handkerchief carelessly on the desk. This infringement of his invariable practice produced even more effect upon Flack than the staring eyes and wavering fingers. Gosling might be guilty of mild histrionics, but not of such a touch as this. The utter neglect of decency exhibited by the display of that shameful bandanna could only portend calamity.

“Lord’s sakes, man, what’s the matter?” asked Flack, still taking an observation under his spectacles.

“It’s come, Flack,” said Gosling feebly. “It’s in Scotland. Our Mr Stewart died of it in Dundee this mornin’.”

Flack rose from his seat and grabbed the telegram, which was brief and pregnant. “Stewart died suddenly five a.m. Feared plague. Macfie.”

“Tchah!” said Flack, still staring at the telegram. “‘Feared plague.’ Lost their ’eads, that’s what they’ve done. Pull yourself together, man. I don’t believe a word of it.”

Gosling swallowed elaborately, discovered his bandanna on the desk and hastily pocketed it. “Might a been ’eart-disease, d’you think?” he said eagerly.

“ We-el,” remarked Flack, “I never ’eard as ’is ’eart was affected, did you?”

Gosling held out his hand for the telegram, and made a further elaborate study of it, without, however, discovering any hitherto unsuspected evidence relating to the unsoundness of Stewart’s heart.

“It says ‘feared,’ of course,” he remarked at last. “Macfie wouldn’t have said feared if ’e’d been sure.”

“They’d ’ardly have mentioned plague in a telegram if they ’adn’t been pretty certain, though,” argued Flack.

Gosling was so upset that he had to go out and get a nip of brandy, a thing he had not done since the morning after Blanche was born.

The partners looked grave when they heard the news from Dundee, and London generally looked very grave indeed, when they read the full details an hour later in the Evening Chronicle.

Stewart, it appeared, had come straight through from Berlin to London via Flushing and Port Victoria, and on landing in England he had managed to escape quarantine. His was not an isolated case. For some weeks it had been possible for British subjects to get past the officials. There was nothing in the regulations to allow such an evasion of the order, but it could be managed occasionally. Stewart had been told to spare no expense.

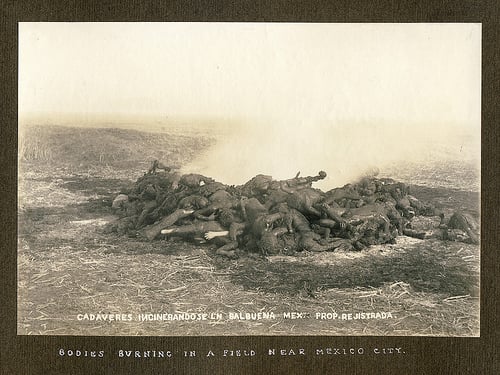

The Evening Chronicle, although it made the most of its opportunity in contents bill and headlines, said that there was no cause for alarm, that these things were managed better in Great Britain than on the Continent; that the case had been isolated from the first moment the plague was recognized (about five hours before death), that the body had been burned, and that the most extensive and elaborate process of disinfection was being carried out even the sleeping coach in which Stewart had travelled from London to Dundee twelve hours before, had been identified and burned also.

London still looked grave, but was nevertheless a little inclined to congratulate itself on the thoroughness of British methods. “We’ll never get it in England, you see if we do,” was the remark chiefly in vogue among the great Gosling family.

But twelve hours or so too late, England was beginning to regret that the Government had been defeated. It was rumoured that the Premier had broken down, had immediately resigned his office, and would not seek re-election as a private member.

This rumour was definitely confirmed in the later editions of the evening papers. Mr Brampton had been summoned to Buckingham Palace and was forming a temporary ministry which was to take office. In the circumstances it was deemed inadvisable to plunge the country into a general election at that moment.

4

Mr Stewart died in the small hours of Friday morning, and the next day, Saturday, the 14th of April, was the first day of panic.

The day began with comparative quiet. No further case had been notified in Great Britain, but telegraphic communication was interrupted between London and Russia, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, and other continental centres. In Germany matters were growing desperate. There had been riots and looting. Military law had been declared in several towns; in some cases the mob had been fired upon. Business was at a standstill, and the plague was spreading like a fire. Between two and three hundred cases were reported from Reims, and upwards of fifty from Paris…

Business houses were being closed in the City of London, and the banks noted a marked tendency among their depositors to withdraw gold; so marked, indeed, that many banks of high standing were glad to be able to close their doors at one o’clock.

It was on this Saturday morning, also, that the bottom suddenly fell out of the money market. For weeks past, prices had been falling steadily, but now they dropped to panic figures. Every one was selling, there were no buyers left. Consols were quoted at 53 1/2.

The air of London was heavy with foreboding, and throughout the morning the gloom grew deeper. The depressed and worried faces to be met at every turn contrasted strangely with the brilliance of the weather. For April had come with clear skies and soft, warm winds.

As the day advanced the atmosphere of depression became continually more marked, and how extraordinary was the effect upon all classes may be judged from the fact that less than 5,000 people paid to witness the third replay between Barnsley and Everton, in the semi-final of the English cup….

In London, men and women hung aimlessly about the streets waiting for the news they dreaded to hear. The theatres were deserted. The feeling of gloom was so real that many women afterwards believed that the sky had been overcast, whereas Nature was in one of her most brilliant moods.

It was a few minutes past three when the pressure was exploded by the report of the final catastrophe. “Two more cases of plague in Dundee and one in Edinburgh,” was the first announcement. That would have been enough to show that all the vaunted precautions had been useless, and within an hour came the notification of two further cases. Before six o’clock, eight more were notified in Dundee, three more in Edinburgh, and one in Newcastle.

The new plague had reached England. It was then that the panic began.

VII

PANIC

1

Gurney, when he left his office on that Saturday, was influenced by the general depression. He went to lunch at the “White Vine,” in the Haymarket, quite determined to keep himself in hand, to argue himself out of his low spirits.

He made a beginning at once.

“Every one seems to have a fit of the blues, Ernst,” he remarked to the waiter with a factitious cheerfulness.

Ernst, less polite than usual, shrugged his shoulders. “There is enough cause already,” he said.

“Have you had bad news from Germany?” asked Gurney, feeling that he had probably been rather brutal.

“Ach Gott! ’s’ist bald Keiner mehr da,” blubbered Ernst, and he wept without restraint as he arranged the table, occasionally wiping his eyes with his napkin.

“I’m most awfully sorry,” murmured the embarrassed Gurney, and retreated behind the horror of his evening paper. He found small cause for rejoicing there, however, and discarded it as soon as his lunch had been brought by the red-eyed Ernst.

“I wonder what Mark Tapley would have done,” Gurney reflected moodily as he attacked his chop.

There were few other people in the restaurant, and they were all silent and engrossed. That dreadful cloud hung over England, the spirit of pestilence threatened to take substance, the air was full of horror that might at any moment become a visible shape of destruction.

Gurney did not finish his lunch, he lighted a cigarette, left four shillings on the table, and hurried out into the air.

He did not look up at the sky as he turned eastwards towards Fleet Street; no one looked up at the sky that afternoon. Heads and shoulders were burdened by an invisible weight which kept all eyes on the ground.

Fleet Street was full of people who crowded round the windows of newspaper offices, not with the eagerness of a general election crowd, but with a subdued surliness which ever and again broke out in spurts of violent temper.

Gurney, still struggling to maintain his composure, found himself unreasonably irritated when a motorbus driver shouted at him to get out of the way. It seemed to Gurney that to be knocked down and run over was preferable to being shouted at. The noise of those infernal buses was unbearable, so, also, was that dreadful patter of feet upon the pavement and the dull murmur of mournful voices. Why, in the name of God, could not people keep quiet?

He bumped into someone on the pavement as he scrambled out of the way of the bus, and the man swore at him viciously. Gurney responded, and then discovered that the man was known to him.

“Hallo!” he said. “You?”

“Hallo,” responded the other.

For a moment they stood awkwardly, staring; then Gurney said, “Any more news?”

The man, who was a sub-editor of the Westminster Gazette, shook his head. “I’m just going back now,” he said. “There was nothing ten minutes ago.”

“Pretty awful, isn’t it?” remarked Gurney.

The sub-editor shrugged his shoulders and hurried away.

Presently Gurney found himself wedged among the crowd, watching the Daily Chronicle window.

A few minutes after three, a young man with a very white face fastened a type-written message to the glass.

There was a rapid constriction of the crowd. Those behind, Gurney among them, could not read the message, and pressed forward. There were cries of “What is it?… I can’t see…. Read it out….” Then those in front gave way slightly, a wave of eagerness agitated the mass of watchers, and the news ran back from the front. “Two more cases of plague in Dundee; one in Edinburgh.”

And with that the pressure of dread was suddenly dissipated, giving place to something kinetic, dynamic. Now it was fear that took the people by the throat: active, compelling fear. Men looked at each other with terror and something of hate in their eyes, the crowd broke and melted. Every man was going to his own home, possessed by an instinct to fly before it was too late.

Gurney shouldered his way out, and stopped a taxi that was crawling past.

“Jermyn Street,” he said.

The driver leaned over and pointed to the Daily Chronicle window. “What’s the news?” he asked.

“The plague’s in Dundee and Edinburgh,” said Gurney, and climbed into the cab and slammed the door.

“Gawd!” muttered the driver, as he drove recklessly westwards.

Sitting in the cab, finding some comfort in the feeling of headlong speed, Gurney was debating whether he would not charter the man to take him right out of London. But he must go home first for money.

At the door of the house in Jermyn Street he met Jasper Thrale.

2

“Have you heard?” asked Gurney excitedly.

“No. What?” said Thrale, without interest.

“There are two more cases in Dundee and one in Edinburgh,” said Gurney. The driver of the cab got down from his seat, and looked from Gurney to Thrale with doubt and question.

Thrale nodded his head. “I knew it was sure to come,” he remarked.

“Better get out of this,” put in the driver.

“Yes, rather,” agreed Gurney.

“Where to?” asked Thrale.

“Well, America.”

Thrale laughed. “They’ll have it in America before you get there,” he said. “It’ll go there via Japan and ’Frisco.”

“You seem to know a lot about it,” said the driver of the cab.

“Do you mean to tell me there’s nowhere we can go to?” persisted Gurney.

Thrale smiled. “Nowhere in this world,” he said. “This plague has come to destroy mankind.” He spoke with a quiet assurance that carried conviction.

The driver of the cab scowled. “May as well ’ave a run for my money first, then,” he said, and thus gave utterance to the thought that was fermenting in many other minds.

There was no hope of escape for the mass, only the rich could seek railway termini and take train for Liverpool, Southampton or any port where there was the least hope of finding some ship to take them out of Europe.

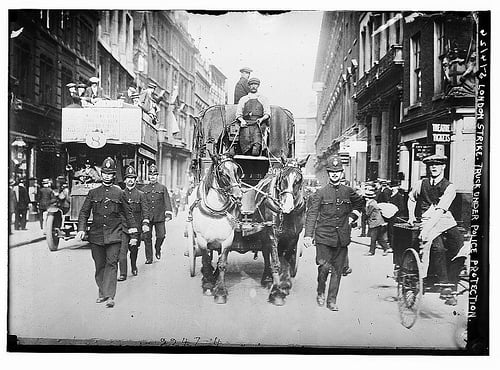

That night there was panic and riot. The wealthy classes were trying to escape, the mob was trying to “get a run for its money.” Yet very little real mischief was done. Two or three companies of infantry were sufficient to clear the streets, and not more than forty people in all were seriously injured….

In Downing Street the new Premier sat alone with his head in his hands, and wondered what could be done to stop the approach of the pestilence. One of the evening papers had suggested that a great line of fire should be built across the north of England. The Premier wondered whether that scheme were feasible. He had never held high office before; he did not know how to deal with these great issues. All his political life he had learned only the art of party tactics. He had learned that art very well, he was a master of debate, and he had shown a wonderful ability to judge the bent of the public mind and to make use of his judgments for party ends. But now that any action of his was divorced from its accustomed object, he was as a man suddenly forced into some new occupation. Whenever he tried to think of some means to stay the progress of the plague his mind automatically began to consider what influence the adoption of such means would have upon the general election which must soon come….

“A line of fire across the north,” he was thinking, “would shut off the whole of Scotland. They would never forgive us for that. We should lose the entire Scottish vote — it’s bad enough as it is.” He sat up late into the night considering what policy he should put before the Cabinet. He tried honestly to consider the position apart from politics, but his mind refused to work in that way….

3

In Jermyn Street Thrale was arguing with Gurney, trying to persuade him into a philosophic attitude.

“Yes, I suppose there’s absolutely nothing to be done but sit down and wait,” said Gurney.

“Personally,” returned Thrale, “I have no intention of spending my time flying from country to country like a marked criminal. That way leads to insanity. I’ve seen men become animals before now under the influence of fear.”

“Yes, of course, you’re quite right,” agreed Gurney. “One must exercise self-control. After all, it’s only death, and not such a terrible death at that.” He got up and began to pace the room restlessly, then went to the window and looked out. Jermyn Street was almost deserted, but distant sounds of shouting came from the direction of Piccadilly. He left the window open and turned back into the room.

“It’s so infernally hard just to sit still and wait,” he said. “If only one could do something.”

“I doubt, now,” said Thrale, quietly, “whether one could ever have done anything. The public and the Government took my warnings in the characteristic way, the only possible way in which you could expect twentieth-century humanity to take a warning a thrill of fear, perhaps, in some cases; frank incredulity in others; but no result either way that endured for an hour…. Belief in national and personal security, inertia outside the routine of necessary, stereotyped employment; these things are essential to the running of the machine.”

“I suppose they are,” agreed Gurney absently. He had sat down again and was sucking automatically at an extinguished pipe.

“In a complex civilization,” went on Thrale “any initiative on the part of the individual outside his own tiny sphere of energy is just so much grit in the machine. There are recognized methods, they may not be the best, the most efficient, but they are accepted and understood. Every clerk who has to calculate twelve pence to the shilling knows how his work would be lightened if he had only to calculate ten, but he accepts that difficulty, because he can do nothing as an individual to introduce the decimal system. And that spirit of acceptance grows upon him until the individual has the characteristics of the class. Only when a man is stirred by too great discomfort does he open his eyes to the possibility of initiative; then come labour strikes. If labour had a sufficiency of ease and comfort, if its lot were not so violently contrasted with that of even the middle-classes, labour would settle down to complacency. But the contrast is too great, and to attain that complacency of uninitiative we must level down. That was coming; that would have come if this plague….”

“What was that?” asked Gurney excitedly, jumping to his feet. “Did you hear firing?” He went to the window again, and leaned out. From Piccadilly came the sound of an army of trampling feet, of confused cries and shouting. “By God, there’s a riot,” exclaimed Gurney. He spoke over his shoulder.

* “Consols were quoted at 53 1/2.” Consol (originally short for consolidated annuities, but can now be taken to mean consolidated stock) is a form of British government bond (gilt), dating originally from the 18th century.

* “I wonder what Mark Tapley would have done.” Mark Tapley is a fictional character in Charles Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit. He is a servant, and his catchphrase is that “There’s no credit in being jolly” under benign circumstances and so he constantly urges himself to find a more challenging set of circumstances in order to test his good spirits.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”