Goslings (3)

By:

September 21, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the third installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

4

One Saturday afternoon Thrale came into Gurney’s chambers and burst out: “Just Heaven! why you fools stand it I can’t imagine!”

“What’s up now?” asked Gurney.

Thrale sat down and drew his chair up to the table. The pupils of his dark eyes were contracted and seemed to glow as if they were illuminated from within.

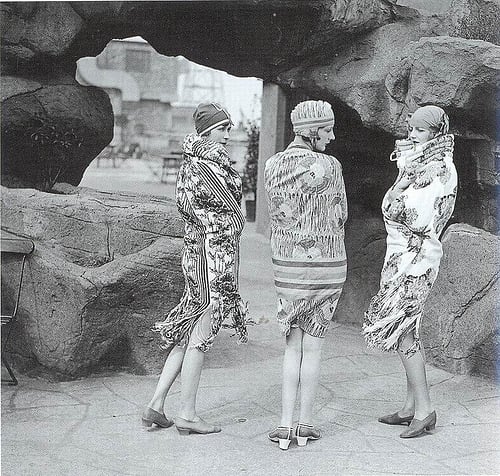

“I was in Oxford Street this morning, watching the women at the sales,” he said. “All the biggest shops in London are devoted to women’s clothes. Do you realize that? And it’s not only that they’re the biggest — there are more of them than any other six trades put together can show, bar the drink trade, of course. The north side of Oxford Street from Tottenham Court Road to the Marble Arch is one long succession of huge drapers and milliners. And what in God’s name is the sense or reason of it? What do these huge shops sell?”

“Dresses, I suppose,” ventured Gurney, “and stockings, underlinen, corsets, hats, and so on.”

“And frippery,” said Thrale, fixing his brilliant dark eyes on Gurney, “And frippery. Machine lace, ribbons, yokes, cheap blouses, feathers, insertions, belts, fifty thousand different kinds of bits and rags to be tacked on here and there, worn for a few weeks and then thrown away. Millions of little frivolous, stupid odds and ends that are bought by women and girls of all classes below the motor-class, to make a pretence — gauds and tawdry rubbish not one whit better from the artistic point of view than the shells and feathers of any half-naked Melanesian savage. In fact, meaningless as the Melanesians’ decorations are, they do achieve more effect. And what’s it all for, I ask you?”

Thrale paused, and Gurney offered his solution.

“The sex instinct, fundamentally, isn’t it?” he said. “The desire — often subconscious, no doubt — to attract.”

“Well, if that is so,” said Thrale, “what terribly unintelligent fools women must be! If women really set out to attract men, they must realize that they are pandering to a sex instinct. Do you think any man is attracted by a litter of odds and ends? Doesn’t every woman sneer when they see some Frenchwoman, perhaps, who dresses to display her figure instead of hiding it? Don’t they bitterly resent the fact that their own men-folk are resistlessly drawn to stare at, and inwardly desire, such a woman? Don’t they know perfectly well that such a woman is attractive to men in a way their own disguised bodies can never be?”

“Yes, old chap; but your average middle-class English girl hasn’t got the physical attractions to start with,” put in Gurney.

“Look at it in another way, then,” replied Thrale. “Doesn’t every woman know perfectly well — haven’t you heard them say — that a nurse’s dress is very becoming — a plain, more or less tightly-fitting print dress, with linen collars and cuffs? Don’t you know yourself that that attire is more attractive to you than any befrilled and bedecorated arrangement of lace, ribbons and gauds? Why are so many men irresistibly attracted by parlourmaids and housemaids?”

“Yes,” meditated Gurney, “that’s all true enough. Well, are women all fools, or what is it?”

“The majority of women are sheep,” said Thrale. “They follow as they are led, and don’t or won’t see that they are being led. And the leaders are chiefly men — men who have trumpery to sell. Why do the fashions change every year — sometimes more often than that in matters of detail? Because the trade would smash if they didn’t. New fashions must be forced on the buyers, or the returns would drop; women would be able to make their last year’s clothes do for another summer. That must be stopped at any cost. Those vast establishments must maintain an enormous turnover if they are to pay their fabulous rents and armies of assistants. There are two means of keeping up the sales, and both are utilized to the full. The first is to supply cheap, miraculously cheap, rubbish which cannot be made to last for more than a season. The second is to alter the fashions which affect the more durable stuffs, so that last year’s dresses cannot be used again. This fashion-working scheme reacts upon the poorer buyers, because it compels them to do something to imitate the prevailing mode, if they can’t afford to have entirely new frocks. That is where all these bits of frilling and what-not come in; make-believe stuff to imitate the real buyers — the large majority of whom don’t buy in Oxford Street, by the way.

“Mind you, there is a limit to the sheep-like docility of women in this connexion. They refused, for instance, to return to the crinoline, and they refused the harem skirt — one of the very few sensible devices of the fashion-imposers. And this in the face of the prolonged, strenuous and expensive methods of the fashion ring. With regard to the crinoline, I think that failure was due to over-conceit on the part of the fashion-imposers. They had come to believe that they could make the poor fools of women accept anything, and on the two marked occasions on which they attempted to introduce the crinoline, the contrast to the existing mode was too glaring. If the fraud had been worked more gradually by way of full skirts and flounces, some modification of the crinoline to the necessities of ’buses and tubes might have been foisted upon the buyers.”

“Oh, my Lord!” ejaculated Gurney; “do you mean to say that women just accept these fashions without any sense or reason at all?”

“You’re rather a blithering ass, at times, Gurney,” remarked Thrale.

Gurney smiled. “You don’t give me time to think,” he said, “I feel like an accumulator being charged. I haven’t had time yet to begin working on my own account. You’re so mighty — so mighty dynamic — and positive, old chap.”

“Well, it’s so absurdly obvious that there must be a reason for women accepting the fashions, you idiot!” returned Thrale. “And the first and biggest reason is class distinction. The women with money want to brag of it by differentiating themselves from the ruck of their sisters, and the poor women try to imitate them to the best of their ability. Women dress for other women. There is sex rivalry as well as class rivalry at the bottom of it, but they dare not put sex rivalry first and dress to please men alone, because they are afraid of the opinions of other women.”

“Sounds all right,” said Gurney, and sighed.

“And we, damned fools of men, stand all this foolishness and pay for it. Pay, by Jove! I should think so! I should like to see the trade returns of all the stuff of this kind that is sold in England alone in one year. They would make the naval estimates look small, I’ll warrant. We even imitate the women’s foolishness in some degree. There are men’s fashions too, but the madness is not so marked; fortunately the body of middle-class men can’t afford to make fools of themselves as well as of their women — though they are asses enough to wear linen shirts and collars which are uncomfortable unsightly and expensive to wash.”

Gurney regarded his lecturer’s canvas shirt and collar, and then stood up and observed his own immaculate linen in the glass over the fireplace. “I must say I like stiff collars and shirts,” he remarked; “gives one a kind of spruceness.”

Thrale laughed. “It’s only another sex instinct,” he said. “Women like men to look ‘smart.’ When you are playing games with other men, or camping out, you don’t care a hang for your ‘spruceness.’ Oh! and I’ll admit the class distinction rot comes in too. You’re afraid of public opinion, afraid of being thought common. If the jeunesse dorée started the soft shirt in real earnest, you would soon be able to persuade your women that that looked smart or spruce, or whatever you liked to call it.”

“Look here, you know,” said Gurney, “you’re an anarchist, that’s what you are.”

“You’re half a woman, Gurney,” said Thrale. “You think in names. All people are ‘anarchists’ who think in ideas instead of following conventions.”

5

Not until he had been staying with Gurney for more than a week did Thrale speak explicitly of his purpose in London. But one cold evening at the end of January, as the two men were sitting by a roaring fire that Gurney had built up, the younger man unknowingly opened the subject by saying, “Things are pretty slack at the present moment. The Evening Chronicle has even fallen back on the ‘New Plague’ for the sake of news.”

“What do they say?” asked Thrale. He was lying back in his chair, nursing one knee, and staring up at the ceiling.

“Oh, the usual rot!” said Gurney “That the thing isn’t understood, has never been ‘described’ by any medical or scientific authority; that it is apparently confined to one little corner of Asia at the present time, but that if it got hold in Europe it might be serious. And then a lot of yap about the unknown forces of Nature; special article by a chap who’s been reading too much Wells, I should imagine.”

“It seems so incredible to us in twentieth-century England that anything really serious could happen,” remarked Thrale. “We are so well looked after and cared for. We sit down and wait for some authority to move, with a perfect confidence that when it does move, everything is bound to be all right.”

“With such an organism as society has become,” said Gurney, “things must be worked like that. A certain group to perform one function, other groups for other functions, and so on.”

“Cell-specialization?” commented Thrale. “Some day to be perfected in socialism.”

“I believe socialism must come in some form,” said Gurney.

“Yes, it’s an interesting speculation, in some ways,” said Thrale, “but the higher forces are about to put a new spoke in the human wheel, and the machinery has to be stopped for a time.”

“What have you got hold of now?” asked Gurney.

“The thoughtful man,” went on Thrale, still staring up at the ceiling, “would have asked me to define my expression ‘the higher forces.’”

“Well, old man, I knew that was beyond even your capacity,” returned Gurney, “so I thought we might ‘cut the cackle and come to the ’osses.’”

Thrale suddenly released his knee and sat upright; then he moved his chair so that he directly confronted his companion.

“Look here, Gurney,” he said, and the pupils of his eyes contracted till they looked like black crystal glowing with dark red light. “Do you realize how some outside control has always diverted man’s progress; how when nations have tended to crystallize into specialized government, some irruption from outside has always broken it up? You can trace the principle through all known history, but the most marked cases are those of the Egyptians and the Incas — two nations which had developed specialized government to a science. There is some power — whether we can credit it with an intelligence in any way comprehensible to us from the feeble basis of our own knowledge, I doubt — but there is some outside power which will not permit mankind to crystallize into an organism. From our, human, point of view, from the point of view of individual comfort and happiness, it would be of enormous benefit to us if we could develop a system of specialization and swamp the individual in the community. And in times of peace and prosperity that is always the direction in which civilization tends to evolve. But beyond a certain point — as the individualists have not failed to point out — that state of perfect government will lead to stagnation, degeneration, death. Now, in the little span of time that we know as the history of mankind, there has been no world-civilization. As soon as a nation tended to become over-civilized and degenerate, some other, younger, more barbarous people flowed over them and wiped them out. In the case of Peru the process had gone very far, owing to the advantages of the Incas’ peculiar segregation. But then, you see, the development in the East, the new world (I ought to explain that I find the oldest civilization of the present epoch in America) reached a point in Spain and England which sent them out across a hemisphere to wreck and destroy the Incas.

“Well, we have now reached a condition when the nations are in touch with one another and progress becomes more general. We are in sight of a system of European, Colonial and Trans-Atlantic Socialism, more or less reciprocal and carrying the promise of universal peace. Whence, you ask, is any irruption to come that will break up this strong crystallizing system which is admittedly to work for the happiness and comfort of the individual? There has been much talk of an Asiatic invasion, a rebellious India or an invading China, but those civilizations are older than ours; if we can trust the precedents of history in this connexion, the conquerors have always been the younger race.” He broke off abruptly.

Gurney had been sitting fascinated and hypnotized by the compulsion of Thrale’s personality; he had been held by the keen, intent stare of those wonderful dark eyes. When Thrale stopped, however, the tension snapped.

“Well,” remarked Gurney, “I think that’s a jolly good argument to prove that we have, at last, reached a stage of universal progress towards the ideal.”

“You can’t conceive,” asked Thrale, “of any cataclysm that would involve a return to the old segregation of nations, and bring about a new epoch beginning with separated peoples evolving on more or less racial lines?”

Gurney pondered for a moment or two and then shook his head.

“Little wonder,” said Thrale, “I had often considered this problem, and I could think of no upheaval which would bring about the familiar effect of submersion. Years ago there was always the possibility of a European war, but even that would have only a temporary effect despite the forecast of Mr Wells in The War in the Air. No, I considered and wondered if my theory was faulty. I was willing to reject it if I could find a flaw….”

“And then?” questioned Gurney.

Thrale leaned forward again and once more compelled the other’s fascinated attention.

“And then, when I was in Northern China, seven weeks ago, I saw a solution, so appalling, so inconceivably ghastly, that I rejected it with horror. For days I went about fighting my own conviction. I couldn’t believe it! By God, I would not believe it!

“There, within a hundred and fifty miles of the border of Tibet, the outside forces have planted a seed which has been maturing in secret for more than a year. There that seed has taken root, and from that centre is spreading more and more rapidly, and it may spread over the whole world. It is like some filthily poisonous and incredibly prolific weed, and its seeds, now that it has once established itself, are borne by every wind, dropping here and there in an ever-widening circle, every seed becoming a fresh centre of distribution outwards.”

“But what, in Heaven’s name, is the weed?” whispered Gurney.

“A new disease — a new plague — unknown by man, against which, so far as we know, he has no weapon. In those scattered villages among the mountains there are no men left to work. Everything is done by women. They are prohibited more fiercely than any leper settlement. No one dares to approach within five miles of them. But every week or two another village is smitten, and the inhabitants fly in terror and carry the infection with them.

“Gurney, it’s come to Europe! There are new centres of distribution in Russia at the present time. If it isn’t stopped it will come to England. And it doesn’t decimate the population. It wipes the men clean out of existence; not one man in ten thousand, the Chinese say, escapes.

“Is it possible that this can be the means of the ‘higher forces’ I spoke of, the means to segregate the nations once more?”

III

LONDON’S INCREDULITY

1

Jasper Thrale’s mission was no easy one. England, it appeared, was slightly preoccupied at the moment, and had no ear for warnings. Generally, he was either treated as a fanatic and laughed at, or he was told that he greatly exaggerated the danger and that these matters could safely be entrusted to the Local Government Board, which had brilliantly handled the recent outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease. But there were some exceptions to this rule.

His first definite statement had been made to his own editor, Watson Maxwell of the Daily Post.

“Yes,” said Maxwell, when he had given Thrale a patient hearing, “it is certainly a matter that needs attention. Would you care to go out as our special commissioner and report at length? …”

“There isn’t time,” replied Thrale. “The thing is urgent.”

Maxwell brought his eyebrows together and looked keenly at his correspondent. “Do you really think it’s so serious, Thrale?” he asked. “After all, what evidence have you, beyond the Chinese reports?”

“I know there are several cases in Russia,” said Thrale.

“Yes, yes; I don’t doubt that,” returned Maxwell, with a touch of impatience. “But unless you can bring evidence to show that this new disease is as deadly as you say, it is not a matter that I could give space to at the present time. For one thing, the Evening Chronicle has been making rather a feature of it for the last three or four days, and I don’t see that I could do much unless we had some special inside information. Then, the House will be sitting again next week, and it seems to me not altogether improbable that we shall have a stormy session, which will mean that a good deal of ordinary matter will have to give way. …” He broke off, and then added, with a friendly smile: “But if you would go out as our commissioner, we should be glad to make you a proposal.”

“There will be no need for a commissioner in a week’s time,” replied Thrale. “You don’t seem to understand that I’m not looking out for a job. I don’t want to write articles; I don’t want to be paid for the information I can supply. I foresee a grave danger, which is growing more grave hourly by reason of the Russian Government’s censorship of all reports referring to the plague. It is a danger which should be understood at once. If you send any commissioner, send the cleverest physician you can find, and a bacteriologist.”

There could be no doubt of Thrale’s earnestness, and Maxwell, who was not only a very capable editor, but also an able and intellectual man, was impressed. Unfortunately, the interests of his proprietors at that moment necessitated a great effort to prop up the very unstable Liberal Government, which had been in power for four years and was now on its last legs. It was so essential from the proprietors’ point of view — three of them were on the Government front bench — that the dissolution should be postponed until such time as the Ministry could go to the country with a reasonable prospect of success. A tentative English Church Disestablishment Bill was to be introduced in the coming session, and it was hoped that if the Government had to go to the country they could make a platform on that one clear issue. It was a good Bill, designed to win the Nonconformist vote, without completely alienating the High Church party. In other words, the Government was eager at that moment to please the majority of the electors, which is, presumably, the highest object of a representative government.

“If it had been at any other time,” said Maxwell, and pushed his chair back.

Thrale understood that the interview was at an end. He rose from his chair and picked up his hat.

“We shall be glad to print any articles you care to send us,” said Maxwell, with his kind smile, “but I can’t undertake a campaign, you understand, at the present moment.”

It was nearly four o’clock, but Thrale just managed to catch Groves of the Evening Chronicle.

2

Groves had his hat on, and was just off to tea at his club when Thrale’s name was sent in to him. He told the messenger that he would see Mr Thrale in the waiting-room downstairs.

Thrale had had some experience of newspaper methods, and he inferred that the reception was equivalent to a refusal to see him. He knew what those interviews in downstairs waiting-rooms implied. It was not the first time that he had been treated like an insurance agent or a tradesman and told, in effect, “Not to-day, thank you.”

In this case he was mistaken in his inference. Groves had had an eye on Thrale’s articles for some time past, and though he thought it a diplomatic essential to keep his man waiting for ten minutes, he had no intention of offending him.

Groves came into the waiting-room with a slightly abstracted air. “Sorry to keep you waiting Mr Thrale,” he said. “The fact is, that I wanted to finish before I left. Did you want to see me about anything particular?”

“Yes,” returned Thrale; “I have some facts about the new plague which ought to be given publicity at once.”

Groves pursed his thick lips and shook his head. “Well, well,” he said, “will you come and have tea with me at the club?”

He took Thrale’s assent for granted, and went out abruptly, leaving his guest to follow.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”