The Unconquerable (25)

By:

December 18, 2014

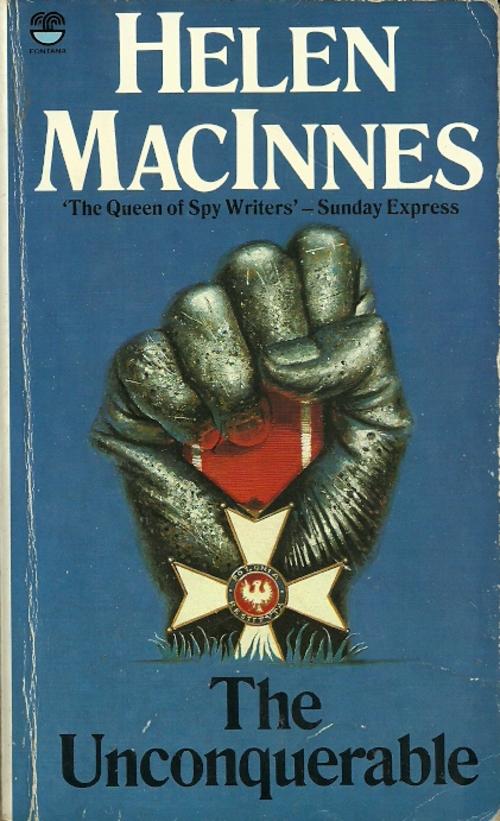

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

Three of the men were waiting in the thickness of the trees. Their faces were alert, their guns held ready.

“The others have gone ahead with the coats and rifles. A good haul,” a short, muscular man said. He looked at Sheila. So did his companions. Their eyes were hard.

“Korytów,” Sheila repeated weakly.

“She’s crying,” Jan said, his good-natured face trying to look as hostile as the others. “She’s scared.”

Sheila shook her head desperately. “Korytów,” she said, her voice breaking on the word.

“Keep moving,” the captain said. “Get away from the road. We’ll question her when it’s safe.”

“Why didn’t you shoot her with the others?” It was the short, broad-shouldered man.

“It wasn’t so easy,” said Jan. “Not when she’s on her knees looking up at you and telling you she’s not dead.”

“The bigger men come, the softer they are,” the other said angrily.

“Quiet. Well get some information out of her before we shoot,” the captain said. “Keep moving.”

The men scattered once more through the trees. The captain wasn’t holding her arm any more, but he watched her out of the side of his eyes. Sheila stumbled on, trying to keep up with the quick lope of the men. The light was fading now, and the army of pines closing in around her increased the darkness. Her heels twisted under her on-the surface roots of the trees. Once she fell forward on her face. The captain waited for her, watching her pick herself up so slowly and men try to run after him. She was too tired to notice that his revolver was held ready to use. He slipped it back into its holster as she came even with him again. He held her arm once more, but this time the grip helped, instead of forcing her along beside him. At last the journey was over. Or at least temporarily over. The men, who had gone on ahead with the German coats and rifles, had heaped them outside a woodsman’s hut in a small clearing. There they had waited for the captain and the others. Nine men altogether. Sheila counted. Three of them, at a signal from the captain, walked separately into the woods. They carried rifles. The rest of the party dropped wearily on the ground.

Now that she could see the sky clearly once more, Sheila knew that evening had come. Night would not be far away. Again she thought of Korytów, and a picture of torches lighting its darkness, of shallow trenches and weeping children, flared up before her.

“Korytów,” she said again.

“She’s always saying Korytów,” Jan remarked. “Perhaps it is all the Polish she knows.”

“Is this as far as we take her?” the short man who believed in shooting her demanded.

“We shall soon know,” the captain answered. He sat down on the soft earth covered with faded pine-needles. “Sit!” he said to Sheila. She obeyed him.

The captain asked quietly, “Where were you going in that car? Where did you come from? Better tell us before we get it out of you.”

“I was going to Korytów,” she began in Polish, and then stopped. She held her aching head in her hands. “Oh, God,” she said in English, “if only I could get my thoughts straight!”

The men round her stopped their quiet talking and looked at her. In her own language the captain said, “Why did you speak English?”

She said wearily, “But I come from England. My family is Scottish. And I can’t think of the right Polish words at this moment. They’ve all gone.”

“Well, we will talk in English then. Two of us understand it fairly. Now go on. You were going to Korytów. Why?”

‘To warn it. The Germans are going to make an example of it. Perhaps to-morrow, perhaps even to-night. I couldn’t find that out.”

“So you travelled in a German car to save a Polish village? Did you intend to bring the inhabitants to safety in that car?” The captain’s quiet irony quickened her reply.

“I’ll answer all your questions. But first send some one to Korytów. We must not waste any more time. Please!”

“We aren’t wasting time. We are going to find out a few things,” the captain said coldly. The broad-shouldered man knew English, too, for he was translating freely to the others.

“Why were you riding in a German car?”

The short man laughed. “Why do pretty blondes in pretty clothes ride in German cars?” he said in Polish. All the men laughed. It wasn’t a pleasant laugh.

The captain shook his head slowly. “That doesn’t explain this case. She wasn’t with an officer. Corporals don’t have large staff cars to take blondes for pleasure-rides.” The men were silent again, and the captain said in English, “Go on. Tell this story of yours.”

“But first send two men to Korytów.”

“First we shall hear your story.”

Sheila stared at the man. And then she knew he was right. Too many traps had been set by Germans.

She told the story quickly. The captain and the man, who disbelieved everything she said quite openly, were listening attentively. Jan had drawn near to listen to the foreign voice. The others stretched themselves more comfortably on the pine-needles and talked together in a low murmur about the ambush.

The story was given simply and as directly as Sheila could manage. She told of her visit to Korytów this summer, of everything that had followed. She didn’t mention Olszak’s name; he was described as “a friend of the Aleksanders’ uncle,” just as Hofmeyer became “one of his assistants.” She didn’t speak of her father, of Uncle Matthews, or of Olszak’s underground movement. These particulars were too dangerous even to be told to the enemies of Germany. But the essential part of the story, the part that would win these men’s trust and help Korytów, was clear enough. When she had finished her hurrying sentences she looked at the men. In the growing darkness she couldn’t see their expressions. Jan, not having understood one word of her story, moved uneasily as if asking her not to expect anything from him. The other two were motionless. Their silence worried her.

“If you examine the papers in my handbag,” she said, “you’ll find my British passport as Sheila Matthews and the forged birth certificate of Anna Braun and the A.O. identification paper and the forged change of name from Anna Braun to Sheila Matthews and the permits which were given me to let me accomplish this journey under false pretences.” Her head still throbbed with a deep, steady pulse, but the feeling of grave danger had cleared her mind. She was seeing things now with a terrifying clearness. What a futile way to die, she thought. How abjectly silly…

There was a rustle of paper. The thickset man held a torch carefully pointed downward. The tall Jan cupped his large peasant’s hands round its weak light. The captain turned over the various pages, studied the text and the photographs and the seals. Sheila watched in an agony of impatience. They were so slow, so thorough, so slow.

At last the torch was switched off.

“Well?” Sheila said. “Will you send some one to Korytów?”

The men ignored her. They talked quickly together. The short man argued.

And then the captain said, “There are some points in your favour. You didn’t use the corporal’s gun on Jan, although it had fallen beside your hand in the car. You didn’t struggle away from us at any time. You made no attempt to escape among the trees when I released your arm. These points are in your favour.”

“Well,” Sheila said, “well ——” Her relief choked her.

“On the other hand, how do we know that your story is really true, that you were not instructed to use it if ever you were questioned by some Poles?”

“Well ——” Sheila halted again. In desperation she said to

the watchful men, “Don’t any of you come from this district? Does no one here know Korytów? He could question me about it.”

“We all belong to this district,” the captain said quietly. “I used to visit the Aleksanders. I know them. What was their house like?”

Sheila plunged into a brief description of the house and garden.

“All very well,” the short man said, interrupting her flatly. “The Germans occupied that house on their push to the east. The Germans could have told you what that house is like.”

The captain nodded, but he called softly to one of his men who was stretched on the ground. The man came forward.

“Your girl lived in Korytów. When did you last see her?” the captain asked him.

“August.”

“Do you recognize this woman here?”

“Can’t say I do.”

“Did you hear of any foreigner staying at the big house in Korytów this summer?”

The man thought over that. “Believe I did. My girl did mention some funny kind of clothes she had seen in the village. Yes, now I think of it, there was a visitor at the big house.”

“Did you hear the visitor’s name?”

“It was one of these foreign ones, twisting your tongue.”

In Polish Sheila said, “Did you know Kawka? How is his mother, who was so ill? Did you know Benicki — Wanda, the little goose-girl — Jan Reska, the schoolmaster? Felix, Maria?”

“Aye, all these I knew. Jan Reska… There was a lot of talk about him and —” The man looked at his captain. He had remembered in time that he was a friend of the Aleksander family.

“Pani Barbara is dead,” Sheila said quietly.

“God rest her soul.”

“And Pan Professor Korytowski has been arrested. Pan Andrew is missing.”

The man said, “He is?” And then slowly, as if the name had struck some thin note in his memory, he added, “I remember now. There was talk he was going to marry the foreigner — that was it. That was why she was there.”

Sheila could feel the captain’s eyes staring at her. Thank God, in one way, for the peasant’s chief interest — gossip. In one way, thank God. In another way — she felt her cheeks flush hotly under the captain’s unseen scrutiny.

“You have said you met Andrew Aleksander in London,” he said softly, “and that Madame Aleksander invited you to Korytów. This last piece of information adds a little more sense to your story, even if it does embarrass you.”

“What about Korytów?”

“I think we’ll let you handle that. We must push on to our camp fifteen miles south of here. We could set you back on me road near the scene of your accident. You could make up a story of lying unconscious in the wood to which you fled. You will find the Germans all right. They will be there by this time. And then you can go on to Korytów and complete your mission there.” He held out her handbag to her.

She didn’t take it. She said dully, “And then I’ll be back with them again.”

“But they trust you. So you told us.”

“Yes. But my luck can’t hold for ever. I managed to scrape through this afternoon at the Gestapo headquarters only because one of the men was despised and distrusted by the others. And because four Nazis were all in different branches of the service. But if I were to meet four Gestapo men, all solidly together —”

“Then why were you chosen for this kind of work?”

“I wasn’t especially chosen or trained. I’ve told you. It just sort of happened. Things have a habit of becoming more complicated than they were planned. If I go back I’ll be deeper in than ever… Streit, the Gestapo man invited me to dinner… He meant it….”

“Couldn’t you handle that?” The Pole’s voice was mocking.

The wind, rustling the pointed pines, had risen to blow away the clouds. Above her head now was a clear sky. The darkness gave way to the half-light of stars. The shadows round her were now faces. She could see the smiles on the two men’s lips.

She rose abruptly. “Yes, I’m a coward. I know that. I want the easy way of disappearing.” It would have been a good way, too. No suspicion on Hofmeyer. Only a minor fanfare for Anna Braun, kidnapped and missing in the line of duty.

“All right,” she said slowly. She passed one hand wearily over her brow, held out the other for her bag. She turned towards the path which had brought her here. Her steps were as slow as her words; her feet dragged. The broad-shouldered man moved quietly round to block her way.

“One moment!” the captain called after her. “Three things I want to know. Who is the man you called your chief — the friend of Korytowski?”

“I can’t tell you that.”

“Who is the man you called his assistant, the man who employed you?”

“I can’t tell you that, either.”

“Why did you say ‘Wisniewski’ down on the road?”

Sheila caught her breath. She answered slowly as if trying to find for herself the reason why that name had come so spontaneously to her lips, “Your men called you rotmistrz. That meant you belonged to the cavalry. So did he.”

“There are several cavalry officers of that name. Surely you didn’t expect me to know your Wisniewski.”

“He was a horseman I thought you would know. Adam Wisniewski. He represented Poland at the international riding competitions. Surely you must know him if you are in the cavalry? I thought that if you knew him and saw that I knew him, then you wouldn’t shoot me at once. You’d give me a chance to explain. All I wanted was not to have a Polish bullet in me. It seems a pity to die so — so unnecessarily. And then…” She hesitated and looked sharply at the listening faces. Did the rest of these men really not understand English?

“And then?” the captain repeated patiently.

“Well, he is doing something of the same kind of fighting as you are. I suppose when I saw a cavalry officer leading a guerrilla attack I thought — at least I suppose I thought — subconsciously of Adam Wisniewski.”

“I think,” the captain said very slowly, “I think we have still more information to find out. Your story was not so complete as it seemed. Sit down. Just how do you know what Wisniewski is doing? When did you last see him?”

Sheila looked at the man who still blocked her path. Jan had moved up obediently beside him.

She said angrily, “I don’t believe you ever meant me to leave. You still don’t believe me. Why did you tell me to go when you didn’t mean it?”

“To see if you would go readily, eager to reach your German friends with the news that our camp was fifteen miles south of this point. I believe you more than I did ten minutes ago.”

“But what about Korytów?” To the man whose girl lived at Korytów she said in Polish, “Korytów is to be destroyed by the Germans. Some one must warn the people to scatter to the woods, to other villages.”

“I can handle my own men, thank you,” the Polish captain said in a hard voice. Then wearily, “Korytów will be your final test. I’ll send two men. If they don’t return or if they find no Germans arrive within forty-eight hours, then we shall know you are too clever to live.”

To the man whose girl lived at Korytów he said, “Go with Jan. Warn the people. Then watch for two nights and two days to see if the Szwaby arrive. You know where to join us. We’ll wait for you there until the night after your watch is ended. Take great care. I may be sending you into a trap.”

From the irritation in his voice Sheila suddenly realized the risk the captain was taking. He was half angry with himself that he should have listened to her. He was torn with doubts between a possible danger to Korytów, probable danger to his men, suspicion of such a story, belief in certain extraordinary details. To hold her as a hostage was the most generous thing he could afford to do. The broad-shouldered man obviously shared none of the part-belief which had been awakened in the captain. Sheila, listening to the captain’s worried voice, knew she should be thankful for even this small mercy. Her own irritation over the slowness of his decision vanished.

Jan was looking at her. He said with a broad grin, “You wouldn’t make me dead, would you, miss?”

Sheila shook her head. She was smiling now. She said to the man who knew Korytów, “Find Pani Marta and the two children, Teresa and Stefan. Tell them they must go to Warsaw and Madame Aleksander. She is ill and alone at Frascati Gardens 37. She needs them.” She opened her bag quickly and searched for her re-entry permit into Warsaw. “No good. Oh damn and blast and damn,” she said in English to herself. The permit was in the decided name of Anna Braun. “Tell Pani Marta she must swear she lived in Warsaw and was a refugee who is now returning. She must do that. Otherwise she won’t get in. Remember: Frascati 37.”

The men nodded, looked to their captain for a sign of dismissal, and then moved silently towards the path back towards the road.

“I’d almost believe she meant what she was saying if I hadn’t seen the results of so many German lies.” It was the broad-shouldered man who was speaking. He stood, compact and solid and watchful.

“Enough, Thaddeus,” the captain said. He stared at the ground before his feet and men looked suddenly at Sheila. His eyes were bitter. If you’ve lost me two good men, by God, I’ll shoot you myself, he seemed to say. For one moment Sheila thought he was going to recall the men and let Thaddeus have his way. He rose suddenly, and moving towards the other men gave them quick orders. They lifted the spoils they had won, wearing part of them, carrying the rest.

An owl gave its sharp cry behind Sheila. She started. But it was the broad-shouldered man called Thaddeus. He repeated the mournful cry as she watched him, and then smiled in spite of himself at her amazement. From three places in the wood came the hoots of other owls, irregular, so natural, that Sheila thought of the three sentries stationed there only after she saw that the rest of the men were leaving the clearing. They scattered, walking singly or in pairs.

The captain said, “I’m afraid I must burden you with my presence. Only keep silent. We have forty-eight hours for talking in the safety of our camp. That will be a pleasant way to pass the time.”

“And if your men don’t return?” Sheila asked wryly.

The officer smiled stiffly, too formally, as if she had made a remark in doubtful taste. “It will still have been a pleasant way,” he said calmly.

The sharply pointing pines rustled in the wind. It was a sad wind, sighing and lamenting. The stars were remote and cold. The other men had vanished into the deep shadows of the wood. Sheila kept the steady pace of the man beside her, and his silence. Beyond the wood were long stretches of solitary fields. Beyond the fields were other woods. Beyond the woods were further fields. The distance was much longer than fifteen miles. Fifteen miles, he had said. Fifteen miles to the south. Yes, fifteen miles to the south for the Germans’ benefit. Fifteen miles to the south for her information if she were in German pay. Now she knew that they weren’t travelling due south, either.

When dawn came mist shrouded the endless plain behind them and the wide forest which lay ahead. Within the shelter of the first band of trees the captain let her rest for ten minutes. And then her heavy feet were following his, deeper into the thickness of the forest. Once he caught her as she stumbled drunkenly against his side. After that he kept a grip of her arm and helped her through the wet, thick underbrush.

“One more mile,” he promised her, looking at her white face. “A short one,” he added encouragingly. Sheila was too tired to answer. She was too tired to smile. She could only try to keep erect, to wade through the heavy white mist which swirled round her legs and hid her feet like the cold hungry surf of a surging sea.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”