The Unconquerable (21)

By:

November 20, 2014

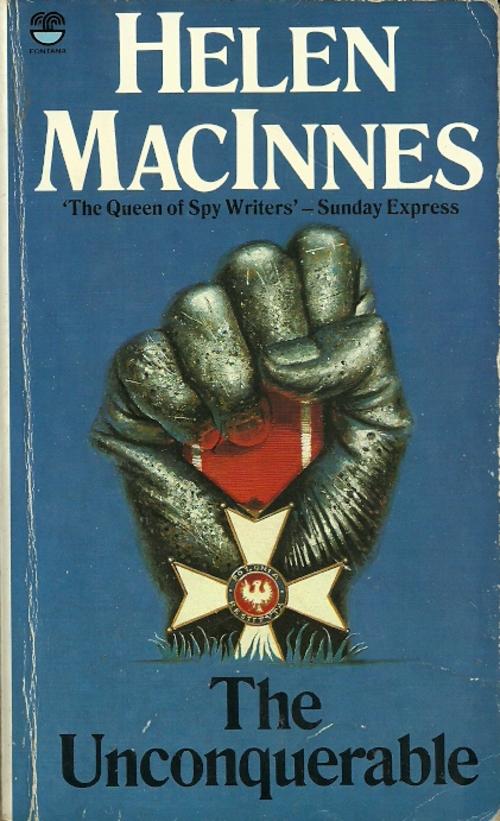

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

Inside the living-room of Stevens’ flat Madame Aleksander and Casimir were waiting. The paraffin which Casimir had ‘found’ now burnt in a lamp which he had ‘discovered.’ Madame Aleksander sat with her legs wrapped in a blanket. Casimir sat at her feet, directing the terrier as it tried to walk backward on its hind-legs. Madame Aleksander was smiling at the dog’s anxious eyes.

“I feel better each hour, Sheila,” she said as the girl entered. “Casimir has been telling me long stories. And he has been teaching the dog a new trick, and it’s trying so hard to please. Just look at it!”

Sheila felt happier as she heard the new note in Madame Aleksander’s voice. The dull, dead tone had gone. She was indeed better, much better.

“I’ll soon be able to leave for Korytów,” she was saying happily. “Casimir is determined to come with me to protect me.”

Sheila bent down to pat the dog as it scratched impatiently for notice at her legs.

“We’ve found a name for him,” Casimir said proudly. “He’s a Scottish dog, so Madame Aleksander said we must give him a Scots name. He’s Volterscot.”

“Walter Scott,” madame said with a smile. “I had to read his novels when I was learning English.”

“Volterscot!” Casimir called and snapped his fingers. The dog cocked his ears and twisted his head to the side. He panted his smile. “See,” Casimir said with delight, “he knows his name!” Volterscot wagged his tail happily, took Casimir’s forefinger gently between his teeth, and paraded before the boy, proudly leading his hand back and forward.

“Volterscot is showing that he owns you, Casimir,” Sheila said. “If I had a nice bone he should have it.” Volterscot deserved more than that, she thought, as she looked at Casimir’s face, young once more, and then at Madame Aleksander watching the boy and dog together.

“I’ll get him one. Somehow,” Casimir said and leaped to his feet with all the unnecessary violence of a boy of twelve. “And there’s our supper to find, too. Have you three zlotys? Prices are awful high, now.”

Sheila counted out five zlotys. About four shillings, she calculated quickly. She always seemed to translate money into English values. “Take good care,” she called after him, but he was already out of the door with a last wave of his hand. Volterscot looked at the two women as if to excuse himself, and darted after Casimir.

“Volterscot, the almost human.” Sheila said, and tried to look as if she felt like making a joke.

Madame Aleksander was watching her keenly, “Did you have a nice walk?”

“Yes. No.”

“That sounds very mixed.” Madame Aleksander looked as if she would like to hear more about Sheila’s afternoon. Sheila said quickly, “And what have you been doing besides getting up against my orders? I must be a very bad nurse if my patient will not obey me.”

“Casimir helped me into this room. It was he who tucked this blanket round my legs. He’s a nice boy, Sheila. I’ve got very fond of him. And then we just sat and talked, and three hours disappeared.”

“I am sorry I was so long.”

“Nonsense. You need more fresh air. You’ve lost the colour in your cheeks. But I’m glad you’ve stopped putting that horrid red stuff on your lips.”

Sheila looked at herself critically in the small mirror over the bookcase. She wondered where she had lost that lipstick. Nowadays everything got lost, and one never seemed to be able to remember where things had been put. It didn’t matter. Nothing mattered but finding something to eat and disguising it as food.

“Pale. But interesting, I hope,” she said.

“And we had three visitors. There was a man about the electric lights. And there was a man to see if the ’phone could be put into order.”

Sheila’s fingers stopped twisting the curls into a pattern over her brow. She turned away from the mirror. “Really? That’s good.” She looked nervously at the walls. Where did they hide those damned things?

“They told me that we should have running water soon. Men are working at the pipes day and night.”

“Good. And who was the third visitor?”

“Mr Stevens. He came to collect the typewriter. He is going away.”

“So soon?”

“To-night.”

“To-night?” Well, the Germans hadn’t lost much time in getting rid of the neutrals. She felt twice as depressed. Parting from friends always made her feel as if she had lost something of herself; as each one went a gap was left.

“Yes. He and another American and a Swedish gentleman called Schlott. It seems Mr Schlott had his business here, but the Germans have taken a dislike to him, and he must leave, too. Mr Stevens is going to be a correspondent in Switzerland for an American newspaper. It is a better job than his old one. Isn’t that splendid?”

“Yes.”

“Sheila, couldn’t you go with him? Can’t you pretend you are an American?”

Sheila looked shrewdly at the blue eyes, too bright in the white face. So Steve had enlisted Madame Aleksander’s help. “And what about a passport?”

“You could have lost it in the siege. Russell Stevens said he and his American friend would vouch for you. The Germans seem eager to get rid of neutrals. Perhaps they don’t want them to see how they are going to treat us.”

“I’m staying here.” Sheila touched Madame Aleksander’s shoulder lightly.

“You must not think only of me. You must think of yourself, Sheila,” Madame Aleksander said gently. She took Sheila’s hand and held it. “I can always go to Edward’s flat. I feel I should have taken you and Casimir there, anyhow. I wonder why Edward and Michal were so insistent that I shouldn’t go there?”

“Wasn’t it bombed?” Sheila asked, her eyes on the wall in front of her.

“He didn’t tell me! What about his manuscript?” Madame Aleksander was nervous again. Her voice was raised, her eyes were troubled. Sheila was sorry she had mentioned anything about the flat, and yet she had had to stop any speculation about Michal Olszak.

“Oh, I don’t think the whole place was destroyed. And you know Uncle Edward. He would save his book first of all.”

“Yes,” Madame Aleksander agreed. She relaxed again, but she was still worried. Her thin hands plucked at the fold of blanket on her lap.

“Why don’t you go back to bed? When Casimir brings back our supper I’ll cook it and bring it to you on a tray. And I’ll read to you.” She looked at the pile of American magazines which Steve had left behind and wondered what story she might find suitable to-night. Madame Aleksander’s taste ran to stories about New England villages, or about ranches in the West, or about plantations in the South. These were her escape from the ruins of Warsaw, perhaps because her life at peaceful Korytów had been a composite of all three.

“Casimir…” Madame Aleksander mused. “Sheila, do you know anything at all about him?”

“Only what I’ve guessed. I think his family were refugees from the West.”

“To-night he told me a little, a very little and yet so much. His mother had long black hair. When she was brushing it it fell beneath her waist.”

“How did you find that out?”

“I was brushing my hair. He was watching me in silence, standing over there at the bedroom door with this blanket over his arm. Then he said that.”

There was a silence. At last Madame Aleksander said, “I am going to take him to live with us at Korytów. I think I’ll try to leave to-morrow, or the day after. The sooner, the better. I’ll never feel really well again until I get there.”

“You must first get official permission.”

“Permission? Korytów is only about forty miles away!”

“It is impossible to travel even five miles without the proper identification papers and a letter of permission. I saw the queue to-day outside the German Kommandatur: people waiting for permission. Sometimes it takes days.”

“Nothing but waiting,” Madame Aleksander said with rising anger. “First we waited for the war, then for news, then for bombs, then for help, then for food and water. We waited to be killed, we waited for word from our families, we waited for the Germans to take over the city. We do nothing but wait. And there’s still more waiting to be done: waiting for the Nazis to be driven back into their own country. But a lot of us here won’t sit around and wait for that day. We didn’t in 1916. After the first shock of this defeat is over I know there will be men who will ——”

“Madame Aleksander, if you want to be strong enough to travel you must rest.” Sheila glanced nervously at the walls. “I thought I heard Casimir,” she said more quietly.

“Oh, he couldn’t be back so quickly. It takes him at least two hours to reach the end of a queue on a lucky day. I’ve timed him. I used to worry about him when the Germans first appeared in the streets. He said he would ——”

Sheila spilled the pile of magazines which she had been examining.

“Sheila, I think you need to rest. How selfish I am, always speaking of my own worries. You are missing England, aren’t you? If you really won’t go with the American I am going to speak to Michal about you, and he will be able to plan something. I have great confidence in him. He’s very clever, and he knows so many ——”

“I am all right,” Sheila said quickly. “I think I’m hungry, that’s all. It seems a long time since supper yesterday. Now do go to bed. Let me help you.”

“If anyone comes asking at this house who you are, do you know what I’m going to say?”

Sheila shook her head. She could only hope it would be nothing that would incriminate Madame Aleksander.

“I shall say you are Barbara.”

“Barbara.” It was the first time they had mentioned her name.

“Who is to know but our family and friends? And no Pole will tell.” Her face looked happier now. “It’s a very good idea of mine,” she said firmly. “I can’t imagine why I didn’t think of it before.” She unfolded the blanket and rose slowly. She looked round the room and forced herself to talk of everyday things. “To-morrow we will clean this place thoroughly. I do wish we had Maria here. She is so good at making things shine.”

Sheila’s amazed look turned to one of amusement. Madame Aleksander didn’t believe anything was well done unless she had at least superintended it herself. Wars may change ways of thinking, but they don’t change instincts. Sheila looked at her hands roughened by so much cleaning and scrubbing. She began to laugh.

“Are you all right, Sheila?”

“Yes. I almost forgot to tell you one piece of good news. I have a job. That will earn enough to buy us food and clothes. You see, some one must make money. Uncle Edward has been robbing himself to provide for us, but he will get no more salary from the University. All the teachers are looking for jobs. Wasn’t I lucky to find this one?”

Madame Aleksander looked doubtful. “What is it?” she asked slowly.

She looked relieved when Sheila explained, although she still frowned.

“But this man’s a German.”

“Of German descent. He is Polish now.”

“And he knows who you really are?”

“Yes, he knows.” That was one truth which the dictaphone could repeat without condemning her.

“Then either he’s a fool or a very brave man.”

“He considers himself a Pole,” Sheila said, and Madame Aleksander gave a strange little smile.

The bedroom door closed gently.

Sheila picked up the magazines which she had dropped, pretended to hum a song, folded the blanket, rearranged the table mat, moved a chair, and then sat down and stared at the walls. I just can’t bear the idea, she thought; I just can’t go on living here with this continual trap around me. She could guard herself; but Madame Aleksander? She still broke into a cold sweat at the innocent remarks this evening which, if they had been completed, might have disclosed enough to the Germans. As it was, Madame Aleksander was convinced that Sheila was heading for a nervous breakdown. She would be worrying now in that room, as if she hadn’t enough to worry about.

Sheila jumped as the telephone bell rang. Was it tapped, too? Probably all telephones were.

“Telephone, Sheila,” Madame Aleksander’s voice called.

“Yes.” She went into the hall and lifted the receiver from the hook as if it exuded vitriol.

It was Steve. She almost wept at the sound of his voice. She couldn’t speak.

“Sheila, what’s wrong with you? It is you, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Say — is anything wrong?”

“No.”

“I wondered if you might have changed your mind. About coming. We are all gathered together in the Europejski, like sheep in a pen. We leave in an hour. There’s just time for you to join us.”

“But I’ve got to stay, Steve.”

“Perhaps you feel you ought to, but there is no ‘got’ about it.”

The operator’s voice said, “That is all the time allowed for a telephone conversation. Have you finished?”

“No, damnation,” Steve said, “Sheila, listen ——”

The telephone went dead.

Sheila had just re-entered the room when the bell rang again.

This time it was Bill.

“Steve wasn’t allowed to make any more calls. There’s a mob of us here. We are allowed one each. How are you, Sheila? Sorry about that night. Remember?”

“I hope Lilli’s well. I liked her.”

“She’s a good kid. But say, Steve’s at my elbow. Why the hell don’t you come with us and stop us all worrying? Schlott is here, too. The Germans didn’t like his face. Just a minute, Sheila, Steve’s jabbering at my elbow.”

There was a slight pause.

“Sheila, he says, and this goes for all of us ——”

The operator’s voice said, “That is all the time allowed for a telephone conversation. Have you finished?”

“Hell, no,” Bill said, “and you know that damned well.”

“I’ll be all right. Don’t worry,” Sheila said quickly as the telephone became blank sound.

There was the same blankness in the living-room. First the Spaniard and the man from Vienna; then the Englishman and the Frenchman; now Bill and Schlott and Steve. She picked up the guide to Munich and started work on it once more. Work. Something to do. Something else to think about than a room which had become too neat and clean and quiet.

It was dark now. The curfew would be on; anyone in the street was to be shot at sight. It was with relief that she heard the door open and Casimir’s voice calling triumphantly, “Got something.”

There was a look of delight on his face. Not even the small piece of salt pork, which he laid on the table along with the two potatoes, could account for such exaltation. Sheila remembered the unexpected quietness of his entry. Usually his clatter on the staircase told every one in this block of apartments that Casimir was returning. His face was flushed with running. His eyes were excited. He made a joke about Volterscot and laughed too heartily.

“What is it, Casimir? What have you been up to?”

The bedroom door opened, and Madame Aleksander appeared fully dressed.

“I thought you had gone to bed,” Sheila began in amazement.

“I decided I was tired of bed. We’ve no time left to be ill now, anyway. I feel better when I am up. Now what have we got to cook this time, Casimir?”

“Casimir’s been having some fun,” Sheila said. She tried to look severe, but the boy’s unabashed smile spoiled the effect.

“What is it, Casimir?” Madame Aleksander asked, with the authority of a woman who has brought up a family and instinctively knows what kind of voice to use.

“Nothing,” Casimir began, “at least, nothing much. Nothing as much as I’d like.” But his grin widened.

And then Sheila remembered the dictaphone. She sat down heavily on the nearest chair and moistened her dry lips.

“I just,” said Casimir, his pride beginning to need an audience after all, “I just ——”

“Sheila, what’s wrong with you?” Madame Aleksander hurried over to the girl.

“I think I’m just weak with hunger. I should love some food. Wouldn’t you?”

“Yes, I believe I should. Even this.” Madame Aleksander looked at the piece of pork curiously. “Once I wouldn’t even have offered it to a dog.”

But Casimir, having once decided to tell, was not to be cheated.

“I tore down a poster,” he said. “One of those anti-British posters the Germans have been putting up everywhere. It showed a picture of the ruins and Chamberlain’s face and one of us pointing at him and saying ‘This is your fault.’ So I just ripped it right off the wall, and then we ran. Didn’t we, Volterscot?”

“You shouldn’t have done it. I’m glad you did. But you shouldn’t have done it,” Madame Aleksander said slowly. “Did any German see you do it?”

The boy shook his head, and Madame Aleksander’s look of anxiety disappeared. “Then that’s all right,” she added. “I’m glad you did it.”

“Casimir, do you know what happens if you tear down posters?” Sheila asked.

“Yes, I know. I saw the bodies to-day.”

“What’s that?” said Madame Aleksander quickly.

“Two boys tore some down last night. This morning six were shot in front of the wall. No one was allowed to remove their bodies all day.”

“Where was this?”

“In the centre of the town.”

Madame Aleksander’s nostrils dilated. “Think they can terrorize us, do they? Think they can ——”

“Please, Madame Aleksander.”

“I’ll go out and tear down these posters myself.”

“You’ll never reach Korytów if you do.”

Casimir looked at Sheila anxiously. “You wouldn’t want these lies on the walls about England, would you?” he asked.

Sheila hugged him suddenly. “I don’t want to see you shot, Casimir.”

“Some one’s got to be,” the boy answered gravely. “If we don’t do these things we shall be slaves. You are glad I did it, Sheila? Are you glad?”

Sheila tightened her grip on his shoulders, with an intensity that surprised them both. She nodded her yes. Casimir’s anxious little face cleared. He opened his mouth, but Sheila laid a finger across his. She pretended to laugh. “You’ve got to look after Madame Aleksander and me, you know. So don’t go and get killed, Casimir. You won’t?” She kept the smile on her lips as she stared at the treacherous walls. She couldn’t bear this, she thought for the second time that evening. How many honest remarks might not condemn good friends? As she returned Madame Aleksander’s curious gaze frankly she made up her mind what she was going to do. Hofmeyer would call it a sign of the amateur. A professional like Hofmeyer himself would either solve it in a more clever way or be able to harden his heart. If her decision was an admission of defeat, then here was one time when she would choose defeat.

“Shall I cook supper?” Casimir asked eagerly. He was so like Volterscot, so anxious to please.

“Yes, do,” Madame Aleksander said quickly, and Casimir lifted the small piece of pork and the two potatoes as if they were precious crystal. Volterscot trotted happily after him into the kitchen.

Sheila didn’t look at Madame Aleksander. She hunted for a piece of paper and a pencil. Where was that stub which Schlott had used to draw diagrams of the city so that she would not get lost? Had he taken it? She searched frantically, feeling Madame Aleksander’s eyes on her every movement. She was thankful that Madame Aleksander kept her silence. Silence was safety. She found the pencil at last, lying in a pot of dry earth which held a wilting aspidistra. She couldn’t find any paper, so she took one of the magazines. Above its title she wrote in English, “I think this room is tapped for conversation, just as all telephone wires are now tapped. Do you understand what this means? I am not exaggerating.”

Madame Aleksander’s brows knitted as she read the message. She looked sharply at Sheila and saw the girl’s desperation. She kept silent and, taking the pencil which was held out to her, wrote her reply among the list of contributors. “Yes. Do not worry. Now I understand. But is this possible?”

On the bottom margin Sheila wrote, “Yes. Believe me, yes. Trust me. Michal Olszak does, but never mention this to anyone unless you want to see me shot.”

Madame Aleksander’s eyes widened. “Sheila!” they seemed to say. “Sheila!” But she still kept silent as they searched for the precious box of matches. They watched the title-page curl into black tissue. And it was Madame Aleksander who crumbled its ashes into powder on the floor, all her housewifely instincts silenced.

“We are just coming,” Madame Aleksander called to Casimir. Her voice was even. Her arm was round Sheila’s shoulder. She has the strength now, Sheila thought; I now depend on her. And she didn’t care if Olszak or Hofmeyer were angry. She couldn’t go to Korytów, leaving Casimir and Madame Aleksander unwarned. After all, Hofmeyer only pretended to serve the Nazis so that he could help their enemies. And that, Sheila decided, was exactly what she was doing now.

Through the unboarded kitchen window the chill wind of a wet night struck shrewdly. The lights were on once more in Warsaw, small flickering lights of candles and paraffin lamps. In the other kitchens which still stood other women and children were gathered round pots of thin brew cooking slowly on the coal or wood stoves which had been resurrected. Casimir had ‘found’ a small stove, had rigged a somewhat leaky pipe-chimney out of the window. Now he was blowing gently, carefully, on the small heap of glowing coals.

“It’s 1916 all over again,” Madame Aleksander murmured. Sheila knew she wasn’t referring only to the cold, the scanty food, the feeble lights of the city. “But we’ll come through it.”

And suddenly to Sheila the sparse pinpricks of light in the darkness were no longer pathetic. In their tragedy was promise. Through the mist which covered her eyes the lights seemed to grow and spread until they touched each other, and there was no darkness left. For a moment there was only one blurred glow. She brushed her eyes with the back of her hand. The darkness and its meagre lights had returned. But the glow and the brightness remained in her heart.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”