RADIUM AGE AI

By:

August 31, 2022

Systems or machines that mimic human intelligence to perform tasks and can iteratively improve based on the information they collect are known, these days, as “Artificial Intelligence.” We’re familiar with AI in our daily lives via advanced web search engines, recommendation engines, intelligent assistants with natural-language user interfaces, chatbots, and the like — all of which involve computers. But in the decades just before Vannevar Bush, Alan Turing, John Vincent Atanasoff, Hewlett and Packard, Konrad Zuse, and others developed the earliest modern computers, we can find the pros and cons of artificial intelligence depicted in proto-sf stories from science fiction’s Radium Age (c. 1900–1935).

I was inspired to pull the following notes together after I was interviewed by Graham Culbertson for AIDEAS — a podcast about “ideas for AI that sit halfway between poetry and mathematics.” Our discussion aired on August 29.

As ever, my Radium Age research was helped immeasurably by E.F. Bleiler’s invaluable reference book Science Fiction: The Early Years.

Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726). Of course, this is well before the Radium Age. Swift presents an inventor who has constructed a room-sized machine designed to allow “the most ignorant Person” to “write Books in Philosophy, Poetry, Politicks, Law, Mathematicks and Theology.” This “Engine” contains myriad “Bits” crammed with all the words of a language, “all linked together by slender Wires” that can be turned by cranks, thus generating all possible linguistic combinations. Squads of scribes produce hard copy by recording any sequence of words that seems to make sense.

Adeline E. Knapp’s (1860–1909) “The Discontented Machine” appeared a few years prior to the Radium Age. Knapp was an American journalist, feminist and author, and partner in the 1890s of the proto-sf author Charlotte Perkins Gilman. “The Discontented Machine,” in which an assembly-line mechanism — a cutting and stamping machine used by a shoe manufacturer — develops consciousness and makes demands upon ruthless employers, appeared in Knapp’s remarkable 1894 collection of semiallegories One Thousand Dollars a Day: Studies in Practical Economics. Excerpt:

“Really, upon my word,” exclaimed Mr. Hyde, impatiently, indignation at the injustice of the charges preferred getting the better of his fear of the strange complainant. “It seems to me that you are a most unreasonable machine. Of course our fortunes depend upon you, to a great extent, though, as you know, the market is full of machines, all willing to do your work if you refuse. But do we not maintain you? What more would you have us do?”

“Pay me wages,” said the machine, “as you do all these movable machines that you call ‘hands,’ and who only, so far as I can see, wait on me, and finish up the minor details of work with which I cannot bother.”

At this Hyde broke into a hearty laugh. “Well, I declare,” he said, “you are a foolish machine, as well as an unreasonable one.”

Spoiler: The machine does not win this contest.

E.M. Forster’s short novella The Machine Stops (1909) takes place in a future civilization in which the outdoors is all but uninhabited. A “Machine” supplies each inhabitant of this global civilization with everything he or she might desire — to a degree where, at this point, few people ever leave their well-appointed apartments. Socialization and entertainment are entirely mediated via the Machine: yes, Forster helped predict the Internet. Who programs the Machine? It’s unclear. When one courageous individual, Kuno, briefly visits the outside world, he’s shunned by his own mother. Later, when the Machine begins to break down, the inhabitants of this utopian society are utterly helpless. Living, or at least existing in a future world the human population of which has retreated underground, Vashti’s is an invisible cage… the bars of which are fashioned by over-solicitous technology, insidiously addictive social media, and an idiocracy born of complacency.

Responding not only to the administered social order of H.G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia (1904–1905), but to his When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), in which contented Londoners live in a multi-tiered underground society, “The Machine Stops” is one of the most brilliant of the many satires to come of Wells’s technocratic optimism. Serialized here at HILOBROW.

R.O. Eastman’s “The Phonographic Apartment” (1910). Johnson’s friend has invented and set up an automated living facility. Lights go on and off, suitable music is played, doors open and close, and so on, all automatically. Johnson, who is stopping over at the apartment, at first enjoys the convenience, but after a time finds himself driven mad by the officious equipment. He steps out of the apartment to disconnect a cable — one thinks of Dave making his way to HAL’s processor core, in 2001: A Space Odyssey; this is another good example of the first-time-as-comedy phenomenon — hoping thereby to shut off the apartment. However, when he reenters he is automatically captured as a burglar. One also thinks of Ray Bradbury’s 1950 story “There Will Come Soft Rains,” about a highly automated house that “survives” the destruction of the city around it.

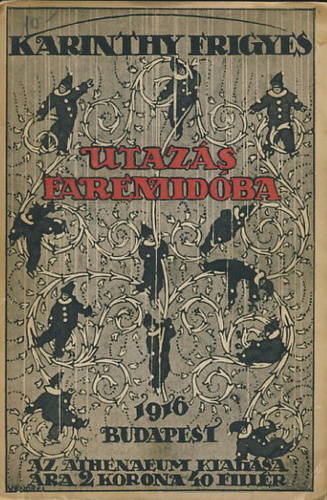

Frigyes Karinthy’s Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage (1916, Hungarian). It’s 1914, and Jonathan Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver is eager to go to sea again. He signs on as a surgeon on a British ship, only to be torpedoed, then picked up by a UFO and transported to Faremido, a planet ruled by intelligent, utterly benevelont machine-folk. They regard organic life as a loathsome disease of matter, so they’re pleased that the Great War looks likely to exterminate humankind; in fact, they have communicated directly with the Earth on this topic, and the Earth agrees. (Karinthy here make the same point that Samuel Butler does in Erewhon — that machines will evolve faster than humans. Unlike Butler, Karinthy admires the perfection of the metal men, and criticizes humankind from their POV.) We learn nothing about the origins of the machines. Agreeing that the Faremidoans (whose society is peaceful, and whose fa-re-mi-do language is musical) are superior beings, Gulliver accepts an injection of their own brain-matter — quicksilver and minerals — into his head. Now a proto-cyborg himself, Gulliver is sent back to England, where he finds it difficult to adjust to the irrational horrors of everyday life. The sequel is Capillária (1921).

Michael Williams’s “The Mind Machine” (All-Story, 1919). After World War I, a planetary cartel known as the International Power and Mechanical Company has emerged, However, at a certain point is employees start turning up dead — associated with them is a blue unanalyzable liquid. Only Doctor Evans, who many years earlier had invented a living machine to handle complicated operations, suspects the truth. The Inner Circle, a revolutionary organization to which he’d then belonged, has been trying to use these machines to seize control of the International Power and Mechanical Company from within… but the machines have rebelled against the rebels too. The machines drive humans out of the cities, which they take over, and for many years mankind dwells in caves far from the urban centers.

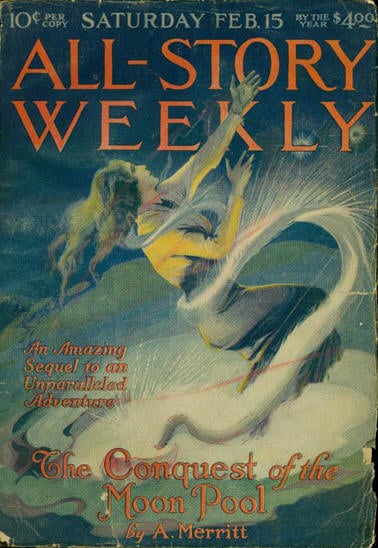

A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool (1918–1919). The scientist Dr. Goodwin, the dashing pilot/adventurer Larry O’Keefe, and others descend into the Earth’s core — in pursuit of an entity that sometimes rises to the surface of the planet and captures men and women. In addition to a lost race of powerful, handsome “dwarves” and a lost race of froglike humanoids, the explorers discover that the entity they seek is the Dweller, essentially an AI created by an advanced race, known as the Shining Ones (ancient astronauts?). The Dweller has the capacity for great good and great evil, but over time is has tended to become evil rather than good. Yolara, a beautiful woman who serves the Dweller, falls in love with O’Keefe; so does Lakla, a beautiful woman who serves the Shining Ones. Fun fact: Merritt was a best-selling author during this period. The Moon Pool, which originally appeared as two short stories in All-Story Weekly, is sometimes cited as an influence on Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu.” Serialized at HILOBROW.

Guy Herbert de Boisragon-Dent (1892-1954), who wrote as Guy Dent, was an author of adventure stories and of one science fiction novel: Emperor of the If (1926). This describes two of the possible universes created by a disembodied brain in a laboratory. In the first part – which is in effect an alternate history – a past in which Britain never suffered from an Ice Age is superimposed on the present, with vivid descriptions of a London overrun by prehistoric flora and fauna. In the second part, the locale is a future dystopia where humans exist under the domination of self-reproducing machines.

How did the machines seize control?

“To start at the beginning, as you’re so ignorant,” he resumed, “I find from my researches that it all started with the invention of poison gas. Men couldn’t face it, so they invented machines to fight from — gas-proof machines. Well, then there was the war to abolish poison gas. That must have been a pretty strenuous time, because I read that there was so much gas used that all the civilian population had to live inside machines as well as the troops. They gave up houses about that time. After that,” he continued, checking each item off on his enormous fingers, “came the war to end the war that was started to abolish poison gas. The first symptoms of revolt on the part of machinery seem to have been noticed then.”

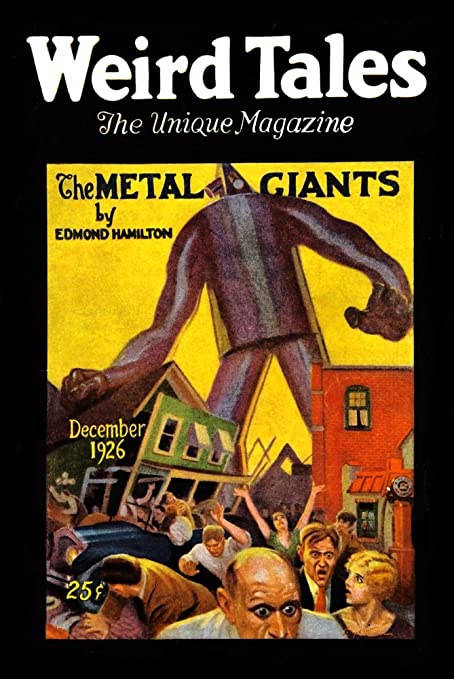

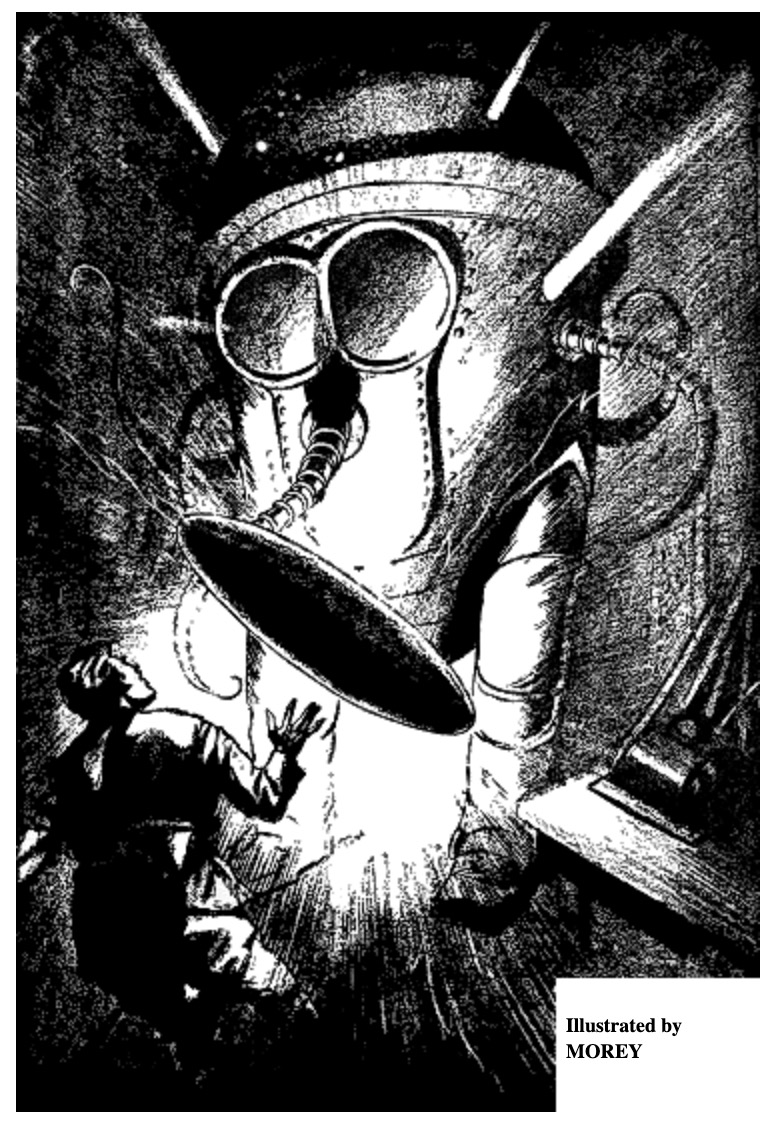

Edmond Hamilton’s “The Metal Giants” (1926) features an atom-powered metal brain that constructs a rampaging army of 300-foot-tall robots.

No doubt it was a startling proposition, to construct an artificial brain that would possess consciousness, memory, reasoning power […] Detmold had attacked the problem from a different standpoint. It was his theory that the sensations of the nervous system are flashed to the brain as electric currents, or vibrations, and that it was the action of these vibratory currents on the brain-stuff that caused consciousness and thought. Thus, instead of trying to make simple, living cells and from them work up the complicated structure of the brain, he had constructed an organ, a brain, of metal, entirely inorganic and lifeless, yet whose atomic structure he claimed was analogous to the atomic structure of a living brain. He had then applied countless different electrical vibrations to this metallic brain-stuff, and finally announced that under vibrations of certain frequencies the organ had showed faint signs of consciousness.

David H. Keller’s “The Psychophonic Nurse” (1928). Excerpt:

“…let me show you how she works. She’s made of a combination of springs, levers, acoustic intruments, and by means of tubes such as are used in the radio, she’s very sensitive to sounds. She’s connected to the house current by a long, flexible cord, which supplies her with the necessary energy. To simplify matters, I had the orders put into numbers instead of sentences. One means that the baby is to be fed; seven that she’s to be changed…”

S. Fowler Wright’s “Automata: I-III” (Weird Tales, September 1929). The first episode of this three-part series — by the British author of The Amphibians, Deluge, and Dawn — is set in the present or near future. Addressing the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the distinguished scientist Dr. Tilwin announces that humankind’s prerogatives will soon be taken over by machines, which are already superior to us in certain ways. Intelligent machines are omnipresent in the second episode, set at some point after the 20th century. By this time, human procreation has almost stopped (Wright, a would-be Wellsian social prophet, was a fierce critic of birth control) and children are increasingly rare. In the final episode, one of the last humans on Earth is drawing a picture — one of the few tasks that machines can’t perform, because it requires imagination. Alas, because he doesn’t properly finish his assignment, he is condemned to be executed.

The steam-plough came, and the petrol-drawn car, and the horse died out to make place for these mechanisms. Few men had realised that the doom of their own race was logically foreshadowed, and that nothing could save them but a war sufficiently disastrous to destroy the world’s machinery and the conditions which could reproduce it.

But such wars as came had only resulted in the subjection of the backward tribes who had not learnt the new worship. The industrial worker had disappeared before the pressure of economic law; the domestic servant before the dictates of fashion. Even in the earliest days the new worship had been established, although it was not then recognised that a new and higher faith had superseded the old superstitions. When the new Moloch called for blood-sacrifice it had been paid without protest or regret, though it would not have been easily satisfied. It sucked blood very greedily, not of single sacrifices, as on the Hittite altars of old, but the blood of thousands. When it was thought that a system of one-way traffic might be conducive to its speed and comfort, the blood of an extra hundred of Londoners had not been grudged to the trial, though their deaths had been foreseen and fore-calculated.

Ships had already been manipulated without crews, and aeroplanes controlled without pilots, and where the helmsman had gone the chauffeur had very quickly followed.

Of course, there had been anger — protest — rebellion. There had been populations, particularly in some of the old urban areas, that had persisted in the production of useless unsanitary children. But such revolt had been futile. The machines had been invincible, and the men who fought beside them had shared their triumph. Even those early machines, directed and controlled by the men that made them, had been irresistible. They had not cried out when they were hurt, they had not slept when on duty. They belonged to a higher natural order than mankind.

Soon it would be a world of machines from which the memory of mankind had died. He did not know that he was the last man living. How should he? But he knew that the last of human births was behind him.

A world of machines — to his feeble, futile brain it seemed lacking in purpose. Yet he knew, as his ancestors had perceived, that the Universe is without consciousness. Scientists had realised, even then, that sentient life is a sporadic outbreak, which, if it had ever occurred, or will do so, elsewhere, is almost incredibly remote and occasional, a mere outbreak of cheese-mites, a speck of irritation, a moment’s skin-disease on the healthy body of a Universe of never-changing law.

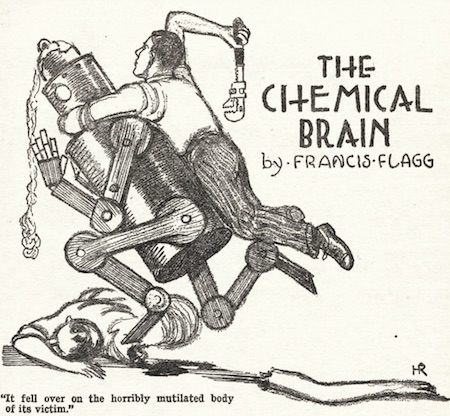

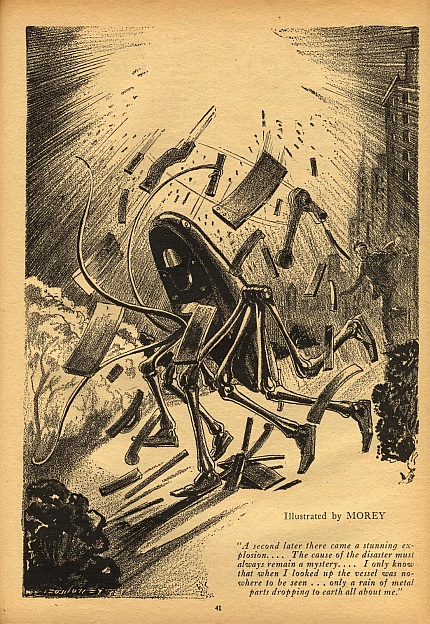

From “The Chemical Brain,” by Francis Flagg. Published by Weird Tales in 1929.

The problem engrossing the captain and me is this: Can we build a mechanical, a chemical brain delicate enough to respond to thought as it now does to sound or other stimuli? Can we give such a command as this to our chemical and mechanical brain: ‘Keep the motor running; every four hours feed it gas and oil’? Can we do more than that? Can we set our machine certain tasks to do, fixing those tasks in its ‘mind,’ and then going away and forgetting it? Don’t you see what that would mean? It would mean the creation of a genuine Robot, an independent metal creature that would work without supervision, eat its daily ration of fuel, and never get sick or go on strike.”

The machine grew under our hands until it was six feet tall. It stood, as I have said before, on rollers, the rollers being encased in caterpillar belts. At the base it was about four feet around, tapering to twelve inches at the top. It was built, not in one piece but in segments, jointed ball-and-socket fashion, with various springs and rubber cushions separating the different parts. To describe it further is beyond me; only it had two armlike pistons, one on each side, possessed a central electric dynamo, and was wired so profusely as to make the interior seem a tangled mass of cord.

Came the day when the brain of this monstrous mechanism was put in place. The part that fitted into what I must call the neck was made of aluminum, all except the cover, which was transparent glass and screwed into place. A small cylinder, which emitted an intense bluish light when brought into contact with electricity, was inside the aluminum howl. The captain connected the necessary wires. His face was very red. I watched breathlessly as Parsons filled the hollow globe with a glutinous mixture of opaque liquid. My hands unconsciously gripped each other until they hurt while I waited for something to happen, but nothing did. He screwed the glass cap into place and stepped down and back from the machine.

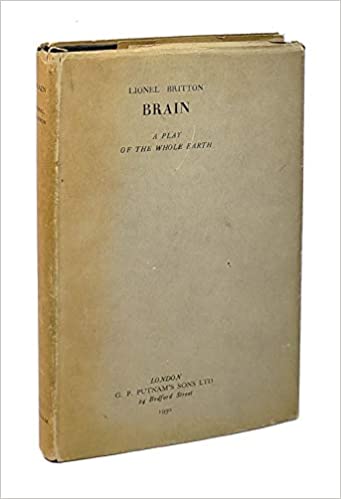

Lionel Britton’s Brain: A Play of the Whole Earth (1930). Depicts an enormous mechanical brain that ends up as the only form of intelligence left on a doomed Earth fifty million years hence. During the first act, circa 1950, a philosopher proposes that a giant computer should be set up to run human affairs according to utopian tenets. In the second act, c. 2100, a Brain Brotherhood is created in order to bring about this vision. In act three, all the action is in the far future; money no longer exists and crime too appears to be a thing of the past; there are no more wars, no private property or distinct classes, and unpleasant jobs are shared equally between everyone; each individual is working towards the improvement of society; sexual inhibitions are a thing of the past and monogamy is not the norm, etc. Brain has become the new God, as indicated by the capitalization of ‘It(s)’, and It lists tasks from an intricate network of activities more or less freely chosen by the people. Anyone with a strong research project can be chosen by Brain to take a ‘B. C.’, meaning ‘Brain-controlled’ research towards a goal which will benefit society; following that, the highest accolade is to be allowed to work within the Brain itself. The computer runs things until nearly the end of the world, when a wandering star collides with the planet. The play received considerable attention because of George Bernard Shaw’s generally favorable comments about it: “The most highbrow play ever produced in England… Had more thought in it than any other play for years… May be acted in every capital in the world.” (Britton was influenced by Shaw’s own proto-sf play, Back to Methuselah.) The didactic play’s message is that without cooperation, the planet is doomed. Brain depicts a harshly sterile world in which any thought against Brain is a mental aberration. This utopia seems at times, we read in Tony Shaw’s 2007 thesis in Britton, to be distinctly dystopian.

Britton, a conscientious objector during World War One gained some prominence in the interwar period for Hunger and Love, Etc (1931), a speculative proletarian/modernist dystopia, written before but published after Brain.

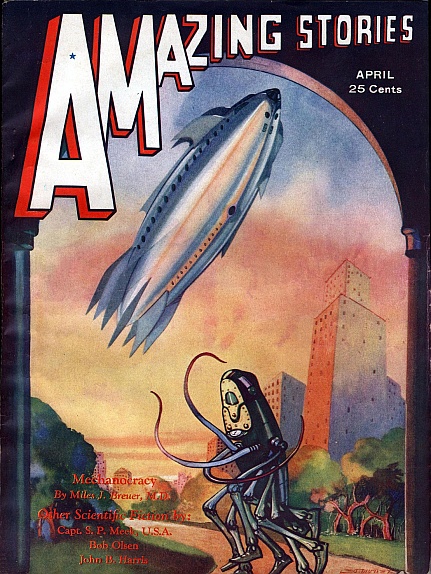

John Wyndham’s “The Lost Machine” (1932, Amazing Stories). A Martian robot is stranded on Earth — and is pursued by humans.

“It was incomprehensible. Why should they be afraid? Surely man and machine are natural complements: they assist one another. For a moment I thought I must have misread their minds — it was possible that thoughts registered differently on this planet, but it was a possibility I soon dismissed.”

Also:

They came upon me as I crossed one of the smooth, green spaces so frequent on this world. My thought-cells were puzzling over my condition. On the fourth planet I had felt interest or disinterest, inclination or the lack of it, but little more. Now I had discovered reactions in myself which, had they lain in a human being, I should have called emotions. I was, for instance, lonely: I wanted the company of my own kind. Moreover, I had begun to experience excitement or, more particularly, apathy.

Laurence Manning’s The Man Who Awoke was initially serialized in five parts during 1933 in Wonder Stories. In 1975 it was published as one complete novel. Norman Winters puts himself into suspended animation for 5,000 years at a time. The stories detail his ensuing adventures as he tries to make sense of the societies he encounters each time he wakes. In 10,000 AD, the world is dominated by the Brain — a super computer that knows all, sees all, and feels nothing. Thanks to its cradle-to-grave supervision, human life is easy and comfortable, but what will happen when The Brain realizes people are superfluous?

John W. Campbell’s “The Last Evolution” (1932).

“Perhaps, this is — a last evolution. Machines — man was the product of life, the best product of life, but he was afflicted with life’s infirmities. Man built the machine — and evolution had probably reached the final stage. But truly, it has not, for the machine can evolve, change far more swiftly than life. The machine of the last evolution is far ahead, far from us still. It is the machine that is not of iron and beryllium and crystal, but of pure, living force.

“Life, chemical life, could be self-maintaining. It is a complete unit in itself and could commence of itself. Chemicals might mix accidentally, but the complex mechanism of a machine, capable of continuing and making a duplicate of itself, as is F-2 here — that could not happen by chance.

“So life began, and became intelligent, and built the machine which nature could not fashion by her Controls of Chance, and this day Life has done its duty, and now Nature, economically, has removed the parasite that would hold back the machines and divert their energies.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin