De Condimentis (9): BBQ

By:

February 10, 2011

Ninth post in Tom Nealon’s DE CONDIMENTIS series.

That was the notion, anyway: regional differences, secret recipes, timeless feuds, hard headed barbecue extremists, assassinations, plots to overthrow the government — who knew what strange fascinations you’d find when you looked into the history of barbecue sauce? Except the very diversity that, on the surface, made barbecue sauce seem such fertile ground for investigation, eventually renders the notion meaningless. There is no barbecue sauce — no unifying element, nothing that brings barbecue sauces together to form a coherent condiment. Like salad dressing is just stuff you put on your salad, barbecue sauce is sauce you put on your barbecue.

Not a single sauce has been “invented” to put on barbecue; instead, they’ve all been repurposed, whether it’s mustard sauce, tomato/ketchup based sauce, tomato/chile sauce, or vinegar- or molasses-based sauce. While they’ve often been tweaked and perfected to a white hot deliciousness, it’s hard to point to any that were conceived for barbecue. There are some dry rubs that are barbecue-specific, but dry rub isn’t a condiment. There is one unifying ingredient — vinegar — but that’s a little thin, so to speak, though as we’ll see, the introduction of European vinegar did spark the last phase of the secret history of barbecue.

Barbecue, from the Taíno barbacoa, the French barbe à queue (from the beard to the tail), the Mayan baalbak kab (meat, cover, earth), and/or the Hungarian bőr bekulni (skin, reconciled) is the slow cooking of foods — usually tough, difficult to eat foods — at a low temperature, usually around the boiling point of water. That’s it. Barbecue slowly evolved over millennia from the ubiquitous, necessary work of cooking things outdoors. Some regions, Europe for example, never really developed anything that could properly be called barbecue, while in other regions it spread like wildfire. In the South they think it has to be pork, and in England (and elsewhere) they think of barbecue as grilling; but barbecue is slow cooking over a low fire, outdoors (or in a pit simulating outdoor conditions). The theory is the same as for boiling foods (where the temperature never exceeds 212 degrees): tough cuts of meat and inedible vegetables are slowly softened and rendered palatable over the long cooking process. The difference is that instead of a great deal of the flavor vacating the food and ending up in the water, most of it stays, concentrated and enriched by heat and a protective veneer (variously banana leaves, corn husks, or, more recently, sauce). The Moroccan tajine, the clay pot for slow-cooking stew, is a barbecue-inspired answer to the boiling problem, and the “Dutch oven” is a more awkward gesture in the same direction.

Barbecue inevitably would have developed from difficult ingredients; if roasting over a fire worked well for every gristly cut of meat or fibrous vegetable, it never would have evolved. But for some foods, grilling or roasting quickly over a direct fire doesn’t work. Slow-cooking traditions developed all over the world in response to intractable foods, and the precursors of what we today think of as barbecue sprang up in Polynesia and the Americas. In Polynesia the reasons are clear: the taro root and pigs (and to a lesser extent dogs and chickens) that the Polynesian people brought with them from Southeast Asia need slow-cooking to be pleasant to eat, and boiling can be problematic for Islanders with limited supplies of fresh water (flavor problem aside). Taro root and pigs, dogs and chickens — it already sounds like a barbecue. In the cuisine of the Americas, barbecue exists early on from the Incan huatia to the (later but still pre-colonial) clambakes in what is now New England. But why? There’s nothing that really screams “slow cook me!” – unlike in Polynesia, pigs were post-colonial in the Americas and the Incan decision to breed the wild cavy (including the immense capybara) down to the size of guinea pigs seems to indicate a well developed shish-kabob tradition (cooking small things quickly — the opposite of barbecue).

It’s a bit of a culinary anomaly, this widespread use of barbecue without an ingredient to drive it. There was a giant capybara that might have done the trick, but it died out somewhere short of human civilization in South America. Polynesia has their own well-documented culinary mystery at about the same time. [Just for the record: There are quite a few people who think that the South American and Meso-American Indians were visited by aliens, and quite a few people who think that the Polynesians, especially the Easter Islanders, were as well. The theory I’m about to spell out works just fine if neither are aliens, or if one or the other are. It’s a little more problematic if you think they were both visited by aliens. For the sake of argument, I’m going to leave the aliens out of it. For now, anyway.]

Anthropologists have been bending over backwards to explain how Polynesians were cultivating the South American sweet potato one thousand years ago. Some have suggested that it floated there after accidentally falling into a boat, others that it just seemed like they’d been growing sweet potatoes for a thousand years before Captain Cook’s arrival. The sweet potato has even caused some archaeologists to re-examine Thor Heyerdahl’s brilliantly bonkers theory that Polynesia was settled from South America. All of which starts to make the alien idea seem plausible, especially considering that in Polynesia the sweet potato is called kumara and in Quechua (the language of the Inca) it’s kumar. And why just sweet potatoes — especially if they’d come all that way?

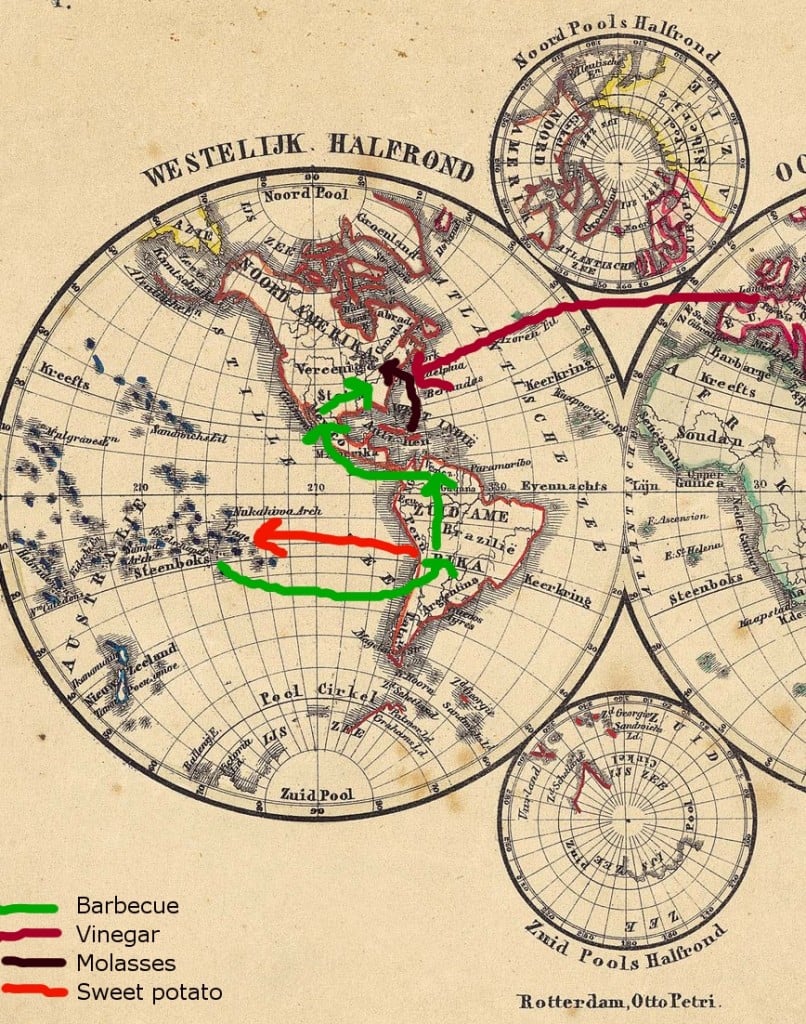

The answer is almost too simple: clearly, the early Polynesians traded the secret of barbecue for the sweet potato. Now, odds are that there was more to the trade — perhaps corn that didn’t survive the journey back, or couldn’t be grown; a few guinea pigs that were so cute the kind hearted Polynesians couldn’t bear to raise them for food; a flock of chickens which promptly ran off into the forest and were swallowed by anaconda. Who knows? What we do know is that the Polynesians sailed back to the Marquesas Islands (probably stopping at Easter Island and perhaps the Pitcairns along the way) and planted these sweet potatoes, while barbecue spread like a delicious, slow-cooked fog over the Americas.

And waited. It took some time for the secret of barbecue to reach what is now New England, but they took to pit barbecuing with zest, using the corn and potatoes also lately arrived from Mexico, along with local quahog clams, crabs, lobsters, mussels, and fish, mirroring the Yucutan fish barbecue tikin xic (post-pig, the Yucutan features cochinita pibil; pit-roasted pork). So when the English showed up (and started boiling everything), barbecue had spread to just about every human habitation in the “New World” — all that remained was to put some sauce on it.

And as you’d expect, “barbecue sauces” follow an east-to-west pattern of decreasing Englishness. Carolina barbecue often consists of a mustard sauce not much different from ones that appeared in medieval European cookbooks and would have been completely recognizable back in London. As you proceed west, you see the appearance of molasses, center of the 18th and 19th century trade between New England and the Caribbean, and then sauces that incorporate more New World ingredients — tomato and chile — while adding that saucy, barbecuing wonder, vinegar. The Wampanoag clambake, Incan huatia, Hawaiian luau, Yucutan pib barbecue, and Maori hāngi — all delicious, it’s true. But don’t feel bad if, when faced with that pile of time-tendered deliciousness, you want to put some sauce on it. Food stops for no one.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.