STUFFED (46)

By:

May 14, 2020

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

I wrote the following essay — inspired by Ole G. Mouritsen and Klavs Styrbæk’s Mouthfeel and Charles Spence’s Gastrophysics — for the Times Literary Supplement in July 2017.

The hegemony of molecular gastronomy has finally receded enough that some of the interesting elements concealed by its ubiquitous froth have surfaced. One such is the new science of gastrophysics, with which two new books grapple, seeking to explain how sight, touch, sound and other sensory and mnemonic phenomena interact with taste. While Charles Spence’s authoritatively entitled Gastrophysics: The new science of eating attempts an overarching study of the field, Mouthfeel: How texture makes taste focuses on one corner, examining the myriad effects of texture on the tasting apparatus. This is an area of inquiry that is a muddle of science and subjectivity, aesthetics and identifiable phenomena. To make sense of it, the authors – Ole G. Mouritsen and Klavs Styrbaek – take us on an often granular tour of the science of texture, the psychology of expectation and how these relate to highbrow modernist cuisine. This curious blend of hard science and finely tuned epicurean sensibilities is more or less expected, given the long relationship between culinary and scientific pursuits.

The two spheres have always overlapped. For more than a thousand years, recipe collections saw food and medicinal recipes run into each other, with no real indication of what distinguished them. The “book of secrets” – a form that rose to prominence during the sixteenth century, collecting recipes for everything from paints and varnishes to cough cures and jam, and that continues to this day (think of popular collections of household hints or DIY ideas) – was the repository of everything left over after obviously culinary recipes and specialized medical instruction had been removed. Even as the Renaissance rolled on, culinary and medical recipes were likely to be found together, often in easy-to-carry editions such as the popular A Choice Manuall, or Rare and Select Secrets in Physick and Chyrurgery, which was customarily bound up with A True Gentlewomans Delight, Wherein is contained all manner of cookery in an eleven-centimeter-tall volume, published well into the eighteenth century. But it was during the enlightenment that capitalism became involved, binding science and food in the manner we are familiar with today: Antoine-Auguste Parmentier campaigned to add the humble and nutritious potato to the French menu, Frederick Accum made the first inquiries into food adulteration, and Count Rumford sought a science for soup to feed the poor. Later, in mid-nineteenth-century Germany, Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company found a way to shrink 30 kg of beef into 1 kg of meat concentrate without losing any nutritional value (or so they hoped – in fact it lost almost all of it and ended up being marketed as comfort food). A few decades on, across the Atlantic, John Harvey Kellogg invented breakfast cereals designed to cure masturbation by removing all extreme flavors that might inflame desire.

But the relationship runs deeper than even this suggests. We think of Brillat-Savarin’s classic Physiologie du goût, ou méditations de gastronomie transcendante (1825) as a classic of the aesthetic enjoyment of food and thoughtful gastronomy; it is easy to forget that the author’s conception of the book was rather different. It is right there in the title – the aim was to fuse cooking and science entirely in an objective physiology of taste that educated people could agree on. It didn’t succeed (which has no doubt contributed to our forgetting that it was trying to), but the notion of fully merging the two disciplines was strong in post-Napoleonic France. The first great pan-Italian cookbook, Pelligrino Artusi’s La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene (1891), attempted something similar. And while it should be noted that some of these preoccupations were part of a small-minded crusade aimed at reasserting male dominance in the kitchen (in America and England in particular, women dominated both kitchens and the cookbook business for most of the nineteenth century), it was simultaneously an embrace of objective knowledge, precision and enlightenment ideals.

As the twentieth century progressed this was brought to bear on nutrition and kitchen technology: vitamins and calories, refrigeration, microwaves and MSG profoundly changed food production and tastes. But in much of the world, the aesthetic enjoyment of food and the science of food drifted apart again. Food was popularly depicted as fuel – ideally cooked quickly and conveniently and, often, swimming in nutrition (a line of thinking that has brought us meal-replacement products such as Soylent); or as a work of art – thoughtful and attractive to the eye, often with a minimalist aesthetic, a thread that connects nouveau cuisine with modernist cuisine.

Mouritsen and Styrbaek’s book attests to a flattening of these seemingly opposed approaches. They begin by considering the idea of mouthfeel obliquely – detailing step by step the complex experience of perceiving and then eating a French fry: “Start by holding the French fry in your fingers. The sense of sight notes its shape, size, and color, and the sense of touch gives an idea whether the French fry is soft or possibly greasy”. On the face of it, this is ridiculous: “after your teeth have bitten through the crust of the French fry, it is time to explore its texture. Is the outside tough or does it yield to pressure? Is the individual piece elastic and soft on the inside, as we would expect of one that is perfect?” But because the authors are talking about the interplay between the five senses and memory, their descriptions really do illuminate the web of science and subjectivity at work. Sensations are repeatedly reassessed – when chewing the fry, do we not rethink and revised first impressions? Was the exterior an accurate indicator of the flavors and the crispness? Did the exterior warmth conceal a tepid interior? These experiences affect taste in ways that the authors tackle in engaging ways, but – probably inevitably given the limited state of current understanding of what attracts certain people to certain foods – it is difficult to agree with their conviction that “when diners in a restaurant express dissatisfaction with a dish, it can almost always be traced back to mouthfeel.”

It is somewhat surprising, then, that serious analysis of this central concept is intermittently lost among considerations of tangential elements, albeit often fascinating ones. Indeed, it is often in the asides and recipes that Mouthfeel takes flight, from its discussion of the textures of insects, and the popular resistance to eating them (with an accompanying recipe for toasted bee larvae with peas), to the ancient Israelites’ rejection of manna (its texture was too uniform), a reenvisioned muesli made with radish and cabbage seeds, maple syrup and pistachios, as well as recipes featuring mouthfeel-expanding elements such as starfish roe, fried fish bones and collagen-rich cod bladder. The science of crispness, the remarkable array of substances that are used to lend thickness and viscosity to foods, the emergent joys of spherification, and the complex and laborious processing that turns bonito fish into the toughest food in the world are lingered on, but how these interact to form an individual’s likes and dislikes is often unclear. The extensive glossary bolsters the book’s place as a helpful reference, but it is difficult to ignore the vacuum at the heart of Mouthfeel.

Gastrophysics, meanwhile, neatly side steps many of the problems inherent in writing about such an inchoate field by speaking in breezy generalities rather than certainties. As a result, we are enticed rather than lassoed into a world where plate shape and colour affect taste as surely as sugar content, and where furry forks do battle with moss-scented quail to enhance our enjoyment of a meal. Some contentions – that humans prefer crisps crunchy and fruit and vegetables with a snap, or that abrasive music can ruin dinner – are perfectly intuitive, but others – that food tastes better out of a bowl, that implanting false food memories can radically alter an individual’s taste, or that Bloody Marys are popular on airplanes because the engine noise dampens all tastes except umami – are more novel. How we think about food, our expectations, our memories – both real and synthetic – of sight, touch, smell, sound and silence conspire to shape how we experience a meal. The methods by which they do so are alternately explained and guessed at, here. Possible future dining experiences emerge: dining with virtual reality headsets; eating from musical plates; restaurants that will have googled us before our arrival, hunting for ways that our waiter might connect with us and enhance our experience. Spence mentions an art project called the Ghost Food Truck which enacted a post-food future where diners ate vegetable protein while breathing “flavoured” air. If all this sounds a little dystopian, Spence assures us that we are not alone in our suspicions.

The contrasting threads that run through this charming book are, on the one hand, the experiments in gastrophysics carried out by cutting-edge chefs at the world’s most unique (and expensive) restaurants, and the uses that this emerging pile of data is being put to by giant food corporations. Early on, Spence explains the lizard brain attraction that humans have for what he calls “protein in motion” – images of oozing cheese, dripping egg yolks and melting puddings trigger automatic cravings. This has not been lost on advertisers. Discussing our brain’s tendency to transfer the characteristics of what we are holding (a glass, cutlery, product packaging) to what we think about the food itself, Spence points out that the majority of us will be exposed to this “new approach” to food and drink through packaging, rather than tasting menus at modernist restaurants. And, perhaps unlike the authors of Mouthfeel, he is well aware that manipulating people’s desires cannot come without a cost. Large sections of Gastrophysics are given over to suggestions on how to recognize when we are being played by companies looking to capitalize on our senses. Talking about the dangers of “food porn” and the flood of TV shows and websites that focus on food images, Spence notes: “We therefore need to expend some mental resources, silly though it may sound, to resist all of these virtual temptations…. In one laboratory study, participants who had been shown appealing food images tended to make worse (i.e. more impulsive) food choices.” Companies will try to entice us with the sound, shape and color of their packaging, and with images of good-looking people eating. They will implant memories – Spence notes that “researchers have shown people’s attitudes and behaviors around food can be subtly influenced simply by implanting false memories related to prior food-related experiences (e.g. telling someone that they once became ill after eating beetroot)”, something which I think ties into much publicized complaints such as MSG syndrome and gluten sensitivity among non-celiacs – and they are almost certain to give smell-o-vision another go. Spence wonders if memory manipulation is inherently unethical – what about if it gets children to eat their vegetables “by implanting false positive memories”? I suspect companies will be less conflicted. Ever the optimist, Spence ends the book with a long list of ways we can spin all this for the good, using the effects that he describes instead of being used by them. Cutting down on consumption is essential and he suggests that we: hide food (even if only in opaque jars); eat junk food in front of a mirror; choose foods heavy in sensation (stronger aroma and more texture aid your brain in determining fullness); eat from smaller plates – eating from a plate twice as big as standard leads to consuming as much as 40 per cent more food – or use red plates, which seem to trigger an avoidance response, or heavy bowls held in your hand while eating, which can make you think you have eaten more than you have.

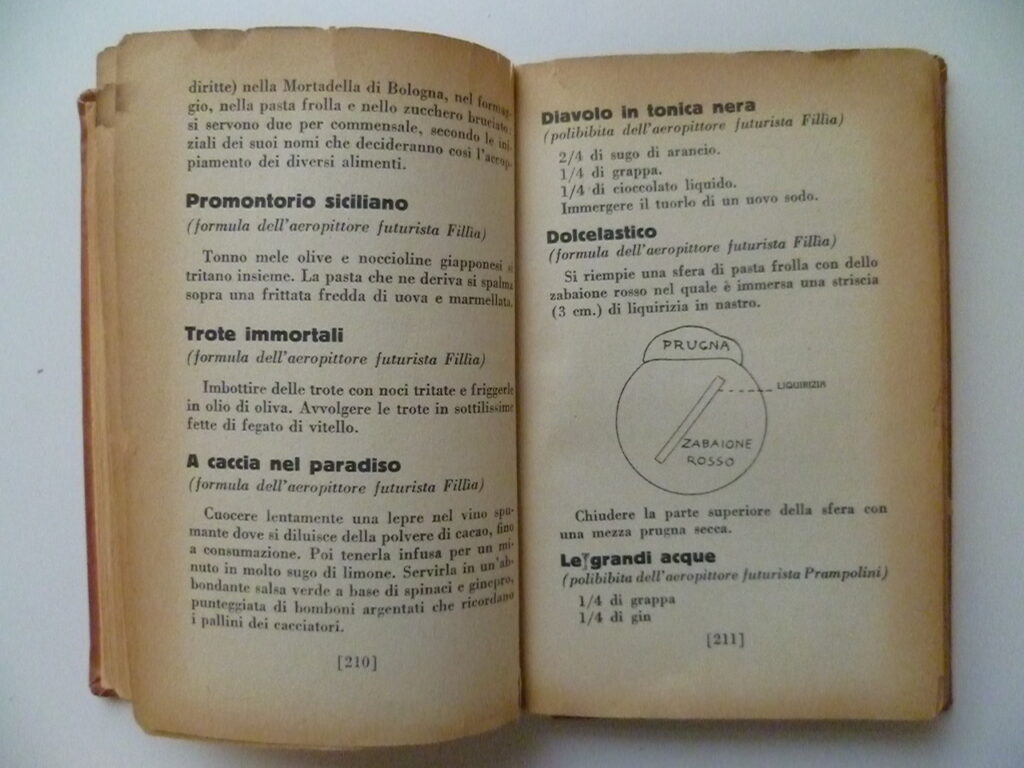

Perhaps more troubling than giant corporations fiddling with our likes and dislikes – though of less immediacy, perhaps – is the connection that so many of modernist cuisine’s absorptions have with those of Italian Futurism, an echo that Spence returns to repeatedly. It is difficult to separate the Futurist program from ethnic nationalism – specifically, Italian Fascism – and this is especially true because Filippo Tommaso Marinetti included a section “Against Xenomania” in his infamous La Cucina Futurista (1932). He labelled as enemies of the Italian state anyone who disrespected the country by, for example, not enjoying national hymns (Toscanini was specifically upbraided for putting “his personal success before the prestige of his country by disowning his own national hymns in the names of artistic delicacy”) or, in the case of some historians, not focusing solely on Italy’s historic military successes. He considered Italian woman who attended American style cocktail parties to be “vulgar and foolish” and suggested Asti spumante get togethers called quisibeve. All of these Leviticus style prescriptions and prohibitions (15 in total with sub parts) precede the description of Futurist banquets. One such repast famously required diners to use their right hand to eat “pieces of olive, fennel, and kumquat” while the left “caresses various swatches of sandpaper, velvet, and silk. At the same time, the diner is blasted with a giant fan (preferably an aeroplane propeller) and nimble waiters spray him with the scent of carnation.” If a friend described such an experience, would you not expect this misadventure to have cost them £350 at a cutting-edge restaurant last Saturday? The Futurists also invented the olfactory dinner party where dishes are passed beneath “diners” noses but no food is ever consumed.

The Futurists were, of course, obsessed with science and speed, famously insisting that Italians stop eating pasta because it was making them slow and docile. One hears echoes of Kellogg’s zeal, the only difference being which pole (energetic vs subdued) was privileged. There was a clear design in mind: by harnessing science the “revolution” would lead to a “strengthening” and “spiritualizing” of “the eating habits of our race… with brand-new food combinations in which experiment, intelligence and imagination will economically take the place of quantity, banality, repetition and expense.” Futurism sought to bring back the vigor of times gone by – namely the Roman Empire – in much the same way as the modern “paleo” diet and similar “clean-eating” movements prescribe a regimen to return us to the greatness of the caveman, or, in any case, simpler, purer times. The manifesto of La Cucina Futurista required “a battery of scientific instruments in the kitchen” that would be the envy of many modern cooks, domestic or otherwise, including ozonizers, ultra-violet ray lamps, electrolyzers, colloidal mills, atmospheric and vacuum stills, centrifugal autoclaves and dialyzers. By placing further discussion of Futurism and its prefiguring of our own modern(ist) cuisine in the final chapter, Spence invites us to add a healthy skepticism to our enthusiasm and raw kale salads.

In 1939, around the time that Futurism was purging the last of its anti-Fascists, the great Soviet enterprise The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food also took a granular interest in its citizens’ diet and nutrition. Its concern for national identity and its embrace of illusion (not even a fraction of the range of ingredients in the book were broadly available) mark it as the kin of Marinetti’s magnum opus. However, unlike the Futurist program, the aim of the Soviet book was to create a vision of a land of plenty, where copious home-grown ingredients could be combined rationally to foster a healthy, productive nation. Historical moments never line up precisely, and Spence’s optimism suggests that he doesn’t necessarily see such projects ending badly – if we are careful. The coming together of science and food needn’t set us on a dark path to a land without pasta and masturbation, and perhaps, as with Brillat-Savarin, we won’t even remember that science was at the heart of twenty-first-century food. Will we return to Spence’s Gastrophysics as a defensive manual against food conglomerates, as a guide to empowering ourselves with food science, or as yet another missed sign of rising (food) fascism? It’s impossible to say, but I am confident that we will return to it.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.